The Value of Buddhism for the Modern World

By Dr. Howard L. Parsons

Buddhist Publication Society

Kandy • Sri Lanka

The Wheel Publication No. 232/233

Reprinted from The Mahā Bodhi (Calcutta) Vol. 82, Nos. 3, 10, 11/1,2 (1974) Digital Transcription Source: Buddhist Publication Society

For free distribution. This work may be republished, reformatted, reprinted and redistributed in any medium. However, any such republication and redistribution is to be made available to the public on a free and unrestricted basis and translations and other derivative works are to be clearly marked as such and the Buddhist Publication Society is to be acknowledged as the original publisher.

The Value of Buddhism for the Modern World

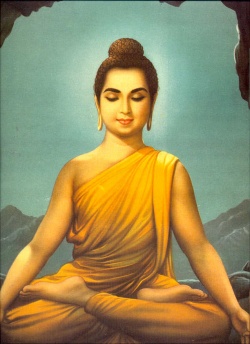

“Every living and healthy religion,” Santayana has said, “has a marked idiosyncrasy. Its power consists in its special and surprising message and in the bias which that revelation gives to life.” What is the special and surprising message of Buddhism? What is the lasting revelation of its leader, Gotama Buddha? We are concerned here not merely with Gotama’s utility for past generations (though that has been great) but with the truth of his moral vision for all human times and hence for modern times.

Let us consider first his conception of the problem of human life, and second his conception of its solution.

I

The problem of our lives begins in the fact that we are always beset by problems. Human life is problematic. Scarcely do we achieve settlement and certainty than we are unsettled by new difficulties. Fixities and finalities elude us. In the words of Gotama’s younger contemporary, Heraclitus of Ephesus, “All things flow; nothing abides.” Heraclitus, like Gotama, must have been caught in that “urban revolution” that swept ancient civilizations, and he must have seen that no perspective, no culture, no standard ultimately stands: “we are and we are not.”

The problem of human life can be expressed otherwise. Man is born without a fixed identity. He is born without instincts—except, if you will, the instinct to live and to learn and to grow. Man is indeterminate at birth. In consequence, his life is a quest; man is a wanderer and a pilgrim, seeking an identity, a role, and a home. Man’s symbolism is both cause and result of this quest. For in virtue of the fact that he acquires and invents languages the continuous choice among many alternatives and roles forces itself upon him, and he lives, unlike the animals, in a tower of Babel; and his attempt to find a determination for his own life in the midst of myriad possibilities drives him to adopt this or that symbolic role for himself. Thus we go through life seeking, asking and knocking—trying to discover who we are trying to fulfil our natures.

The ultimate problem of life, which man has sought to solve through his religious activity, is just this: Who am I? How might I and others achieve the most abundant fulfilment possible? This problem expresses itself at two levels. First of all, man is incomplete in so far as the basic hungers of his body and personality go unmet. The power of these needs is coercive; and when they are not fulfilled man experiences pain. Primitive religion is primarily an attempt to cope with such pain, through various techniques. But man is incomplete and consequently questing at another level. Not only do his appetites lack completion; something else cries out for fulfilment. Not only does man seek food, crops, game, a mate, children, a long and approved life; man wants an identity and a fulfilment greater than any of these particular fulfilments. Not only does man undergo privation and pain and eventual death; he knows, as Pascal says, that he dies. And so he enters into the realm of suffering.

Suffering arises out of a sense of the difference between what is and what might be. It is the tragic sense. It is the realisation that creative possibilities have not or will not be fulfilled: that man can never fully “find” or complete himself; that time is greater than one moment, and eternity vaster than time; that death conquers individual life, but that collective life transcends individual death; that no matter how rich or full a single life may be, it cannot begin to encompass the richness and fullness of the multiform cosmic life around it, and is destined to be singular and lonely in the 2

midst of that great abundance. Even the primitive religions represent inchoate efforts to deal with this problem and to find a fully satisfying identity. The advanced religions of mankind give overt expression to this side of man’s problem—his suffering—and endeavour to cope with it, in thought and action; and Gotama must be seen as one of those who thus struggled with the problem of suffering.

There is a secondary aspect to the problem of human suffering. Our deep desire to find an identity leads to the adoption of some role which at the outset seems to satisfy the need for identity yet at the same time frustrates that very need; for we are often not fully satisfied with one particular role, yet our very adoption of it, necessitated by our need, has led us to take it up with fervent loyalty and, perhaps, with idolatry. We continuously seek closure in our meanings and identities, yet we cannot tolerate the constrictions they lay upon us, for we demand newer and deeper identities. Moreover, if we live long enough, the processes of living crack open the closures we have built and force us to construct new meanings and roles. Thus our roles come to dominate us; we fain would let them go, yet we cannot. So we find that we are enslaved by our own desire for freedom. Our quest for identity seems doomed. For this inveterate desire for identity issues in habits and in character-structure which is well nigh impossible to break and which must yet be broken if we are to be liberated and saved from constriction and death.

In Paul’s language, “the good that I would, I do not; but the evil which I would not, that I do. O wretched man that I am! Who shall deliver me from the body of this death?” We are doomed to this kind of death in life because we are caught up in a partial commitment and in the domination of a demonic good. This death is not physical annihilation but is on the contrary the torture which one must suffer who cannot die; it is, in the language of Gotama’s India, karma and rebirth; it is the perpetuation of compulsive passion and the continuation of that fatal winding of a chain (nidānas) of events which begins in indigenous ignorance and issues always in suffering. For while in a sense we do die when the object of our devotion and the symbol of our identity changes or passes away—since “decay is inherent in all compound things”—yet our dispositions (guṇas, as the Saṅkhya calls them) persist and continue to give rise to the same old structures of habit of the same old Adam.

The whole doctrine of the non-existence of the soul (anatta-vāda) and that of “dependent origination” are designed to deal with the age-old problem of the past and to do so in a way that lends the problem to moral solution. To say that rebirth takes place without anything substantial migrating (after the manner of a seal being pressed upon wax) is to say that a man’s past character is his fate but that he can moment by moment change his character. These doctrines have both a metaphysical and moral advantage, because they avoid the tyranny of eternalism and the hopelessness of nihilism. To describe our suffering as caused by dispositions and habits is to take the first step toward their removal.

Buddha’s personal success and widespread appeal lie partly in the directness of his approach. He begins with the prime fact of unhappiness. Pain and suffering are recurrent and unceasing. We crave and yearn for what is or what is not; and when we obtain it, we yet yearn for more. We, like all things, change: health passes into sickness, youth into old age, and life into death. But we insist on setting our hearts or minds on something that does not seem to change—and we always suffer disappointment. Yet, even to have what we want is pain; for no matter what we want or what we get, we are never satisfied. Man oscillates, as Schopenhauer says, between the restlessness of need and the boredom of satiety, and his will is forever uneasy. Lacking a generic sense of satisfaction, man cannot help feeling that his life is a mistake and a miscarriage; he suffers, in Spinoza’s language, the sadness that is deeper than any specific disappointment or ennui; that is the sadness of the life-urge itself, the sadness of impotence. 3

If we suffer, what are we, and what are the sources in us that lead to suffering? Much of traditional religious and philosophical thought directly contradicts the answer that Gotama gives to this question. That thought holds that in the midst of untruth, darkness, death, incompletion, change, and time, there abides a truth, light, life, completion, permanence, and eternity to which man must turn if he is to be saved from suffering; man’s primal error, therefore, consists in his “fall” from this domain of permanence into the domain of change, which he mistakes for the permanent. But Gotama’s analysis is different.

He does agree with traditional Hindu thought in asserting that man’s first major mistake is to take as real and important what is at bottom illusory, namely, the empirical self. But he radically departs from that tradition and indeed all the great religious traditions by holding, like Hume, that the self is nothing more than a complex of ingredients, a bundle or a stream of matter and of perception, a collection of body, mind, and formless consciousness.. Here he typically rejects two logical extremes, materialism and idealism (and their uneasy compromise, dualism). Not only is there no permanent self; there is no permanent ātman, within or beyond, human or super-human; there is nothing permanent, here or here-after, to which man can turn for guidance, succour or refuge.

The term “self”, therefore, has no fixed referent, for what it commonly denotes is, in time, a changing stream, and, in space, an aggregate of five khandhas or “graspings” bound together in an interaction that forever changes. These graspings—the body, feelings, ideas based on senseperception, instinctual and subconscious drives, and conscious evaluations—are the essence of the organism and its individuality, if we may speak of that. The organism and its parts clutches, selects, and organises; it prehends, in Whitehead’s sense, its world; it lays hold of, completes, forms, transforms, and retains its world. These khandhas are the seat of our loves and hates, hopes and fears, joys and sorrows; for they are polar, and as such participate in the pervasive and ceaseless opposition in the world. To act on the presupposition that our self is identical with these khandhas is to be clutched by their clutchings and to be caught up in their oscillations and to suffer the sadness or disappointment or the outworn satisfactions which they undergo.

Man’s problem is that, in the midst of incomplete meanings and values, he is driven to find and assert some form of completion, but his assertions, however satisfying and complete they seem to be, never ultimately satisfy and always remain partial and mutable. No matter what the self identifies itself with, it cannot seem to find a final and sovereign identity. In time, the self is a stream, and with great penetration Gotama analyses the causal chain that leads him backward from suffering to its ultimate source. We should not suffer had we not first been born as a result of our predisposition to birth and, behind that, our mental clinging to objects. Clinging is due to thirst or taṇhā—the consequence, in turn, of sense experience, senseobject contact, and the organs of knowledge. These led us back to the embryo and its cause in some incipient awareness—the product of experiences in some past life, which derive at last from ignorance or avijjā. Avijjā is the blindness of all organismic striving; it is the Greek eros, Hobbes’ “appetite” and “aversion,” Spinoza’s “power,” Schopenhauer’s “will to live,” Nietzsche’s “will to power,” and Bergson’s “elan vital.”

We suffer. Why? We are driven blindly to hold what we have and to obtain what we have not. In our consciousness we keep and cling to what we are and have; in the depths of our unconsciousness we return to what we have lost or have imperfectly kept, and seek to grasp it firmly, re-enacting the tragic temptation of Faust: “Ah, still delay, thou art so fair.” And why? We know not why. And this ignorance of ours is the root of the whole matter.

In a word, it is our own illusory habit-structure, taken as real and all-important, that destroys us. Behind that lies our tendency to grasp things and fasten upon them as final—our ignorance. We believe in the wrong things because we blindly grasp at any image that seems to promise closure, meaning, satisfaction, and fulfilment. For Gotama “what is impermanent is suffering, 4

what is suffering is not I; what is not I is not mine, it is not I, it is not myself.” Salvation is achieved by both an intellectual and active conquest over the craving or thirst that bedevils man. It is achieved by non-attached work, work which no more elicits self-destructive loyalties than the sowing of fried seeds elicits plants. Such work carries a double blessing. It saves the doer from involvement, and it ministers objectively and hence effectively to the person or situation.

Man “hankers” after the world, says the Buddhist literature, and as a result is “tainted” by lusts, by the desire for continued sensuous experience, and by ignorance. Passion, aversion, and confusion beset him. In the vivid words of the Dhammapada, “The thirst of a thoughtless man grows like a creeper; he runs from life to life, like a monkey seeking fruit in the forest.” He is on fire with the fiery movement of the world. Buddhism has been criticised because in its attack on the “self” and “selfish” craving it has appeared to contradict its contention that the self is illusory and, further, that the self enjoys nirvana.

But this criticism springs from the failure to understand that when Buddhism attacks selfish craving it attacks something partial, selflimiting, and demonic. The self of our desires and values does have power so long as we delegate it that power. The centre of this partial and illusory “self” is man’s basic biotic tenacity as conditioned by culture—his craving for the things and values of the world. But “the world,” as the Idealists have insisted, is always “my world;” the world which I have and cherish in apperception and action is my ego; it comprises my loyalties, my source of support and affection, my role, my identity. To crave, love, preserve, protect, and defend one’s world, therefore, is to crave, love, preserve, protect, and defend one’s self. Trespass on a man’s property and you trespass on him; ridicule a man’s ideas and his world-conception, and you ridicule him.

Craving entails clinging, and the root of clinging is demand. We not only want what we want; we demand it. We move heaven and earth to get it; we turn reason into rationalisation, honour into chicanery, people into means, and opportunity into expediency, in order to get what we want. We cannot live without it, and if we must go without it we see to it that others will share our misery and go without it too. Why do we not only demand things but also demand that, once had, they must be kept? Here, Gotama’s answer, by implication, is close to that of Jesus; we feel anxious for our life. Gotama put it positively: we are driven by an ignorant impulse to live and to build our lives around the forms of our values. Thus we tend to elaborate and integrate our way of life as though it were the be-all and the end-all of existence, and when it is threatened we fight desperately in its defence.

We tend to weave the loose threads of meaning in our lives into some pattern of personal identification. We tend to bring into closure the qualities and forms of our experience and to endow that closure with some character of finality in importance. The closures we choose will vary with body-type, temperament, cultural tradition, and socio-economic condition. They will be predominantly personal and idiosyncratic or will reflect the dominant ideology of environment: idealism, vitalism, or materialism; aristocracy, or democracy; the authority of law, force, or sensuous satisfactions. We tend to invest such meanings with impervious or charismatic powers; at last it becomes difficult to undo our belief and loyalty toward them.

Anyone who has sought to change himself or others or the social order which sustains us knows the truth of the view expressed in “The Authoritarian Personality1”: “The transformation of our social system from something dynamic into something conservative, a status quo, struggling for its perpetuation, is reflected by the attitudes and opinions of all those who, for reasons of vested interests or psychological conditions, identify themselves with the existing set up. In order not to undermine their own pattern of identification, they unconsciously do not 1 Adorno, Theodor W., “The Authoritarian Personality”, New York, Harper (1950). 5

want to know too much and are ready to accept superficial or distorted information as long as it confirms the world in which they want to go on living.” Thirst, craving, taṇhā, not only expresses itself in the demand to have and to keep; it involves the “great refusal” to consider alternatives to one’s beliefs and way of life and indeed positive resistance against what encroaches on what one views as all-important, namely, one’s world, one’s world view, one’s self. And this stubbornness persists often in the face of great suffering. II

What is the solution? We may mention four (among others) responses that are required on the part of man if he is to be delivered from the continuous wheel of unhappiness and to find fulfilment in this life. They are: understanding, renunciation, resolution and compassion.

(1) An indispensable attitude is understanding. This is indicated by the nature of our malady, avijjā, which is literally lack of vision or insight. Where there is no vision—spiritual vision—the people perish. For without vision we are blind, and our efforts to save others become the blind leading the blind. Blindness is the brute, unconsidered belief that what lies before us as the object of our appetite or aversion is real; that the whole complex of our sensuous experience is ultimate; that this complex comprises our being and that nothing more exists; that when this goes all goes; that our whole duty consists in preserving that complex of perception and self against change and decay; and that we ought properly to fear for its passing. Ignorance, in short, is not only impulsiveness, “a perpetual and restless desire of power which ceaseth only in death,” in Hobbes’ phrase; it is the blind demand for the sustenance and preservation of that impulsiveness.

To understand, therefore, is to understand this primal fact of the primate creature. To understand is to delay immediate response and belief; to check readiness and tendency to clutch; to transmute stimuli into signs and signals into symbols; in short, to see the world and ourselves for what they are, namely, appearances in passage. In detail, right understanding or right views involves a knowledge of the four noble truths: the problem of suffering, the cause of suffering, the solubility of the problem, and the solution or eightfold path. Understanding, therefore, is the master-key which unlocks the door to liberation. But it is also a watchful eye which must be ever vigilant, since passion, aversion, and confusion ever dog our steps.

For lest we be destroyed by ignorance and the craving and clinging which come from it, we must ourselves, with active understanding, destroy the source of our destruction. Understanding is thus not to be theoretical or speculative; is not even to be theological, nor to develop the subtleties of psychology. It is to be directed to the immediate problem of the removal of the cause of suffering, as a physician would seek immediately to remove an arrow from a wounded man. This practicality characterises many of the great religious founders and prophets; and this is why it is impossible to ascribe a definitive theology or creed to them; they plunged ahead, to sweat it out on the job before them. This is why, too, diverse theologies and psychologies have followed in their train: the same set of human values may be justified by a variety of theoretical schemes. The problem of human life is not to grasp the metaphysical secret of the world, as Gotama knew from personal experience, or to transcend it by mortification of the flesh.

The problem is not merely to understand it, but, as Marx would say, to change it through understanding it. The problem, as Henry N. Wieman has put it, is for one to probe beneath the conscious beliefs and habits of the mind to the concrete reality that in fact sustains and fulfils one, and indeed to “relinquish every belief as the basis of his security”, finding “what operates in human life with such character and power that it will transform man as he 6

cannot transform himself, saving him from evil and leading him to the best that human life can ever reach, provided that he meets the required conditions.” Thought, therefore, must pass beyond its abstract task of analysis and synthesis to the practical task of saving man from his suffering and carrying him over into fulfilment. This task of thought has not always been consistently or effectively pursued in Buddhism; it has tended to overestimate the power and importance of the conscious mind. But certainly its original aim was pragmatic, and the spirit of Gotama is existential rather than intellectual.

The importance of thought in the viewpoint of Buddhism, cannot be underestimated. It is stated in the very first verse of the Dhammapada: “All that we are is the result of what we have thought: it is founded on our thoughts, it is made up of our thoughts. If a man speaks or acts with an evil thought, pain follows him, as the wheel follows the foot of the ox that draws the carriage.” The source of our lives and hence of our happiness or unhappiness is, in Buddhism, entirely within our power; were this not at least partially so, then we should all be victims of personal karma or the arbitrary power of historical and natural processes. And the source of our lives is our thought. Since a good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit, neither can a corrupt tree bring forth good fruit, and since we all seek the good, the moral for human action is plain.

Understanding brings mastery and a sense of inner strength, not alone in the consequences it produces but also in its intrinsic quality. To understand is to see that “all forms are unreal … all created things are grief and pain … all created things perish;” it is to trace out the lineaments of things in their internal structure and their relations to other things in space and time; it is to acknowledge the paths of necessitation which things pursue as they come into being, change, and pass away. Truth in this sense induces tranquillity and strength in him who possesses it and whose mind is moulded and purified by a selfless acquiescence in the nature of things. For truth, as Spinoza observed, expels and purges that sense of impotence and sadness, that fear and hatred, which come when we are made slaves to the forces and fates of the world. Truth, by its power to lift us above what is circumstantial and passing, also lifts us free of those “passive” emotions which play upon our affections willy-nilly and undermine our integrity.

When we can be like a Buddha who “by himself thoroughly knows and sees, as it were, face to face this universe—including the worlds above, the gods, the Brahmas, and the Māras, and the world below with its recluses and Brahmans, its princes and peoples,” then we will indeed be liberated from human bondage and know what it means to speak of the truth as “lovely in its origin, lovely in its progress, lovely in its consummation.” Understanding can issue in that fortitude which expresses itself as strength of mind and generosity (as Spinoza said) because it is an active attitude that clears up the confusion of blind impulse and its passion. While to some Western minds, influenced by the spirit of experimental science, understanding in this sense may seem to be passive and quiescent, it is in fact a tremendous act of labour, involving a penetration into the nature of human life; a continued mindfulness of what it has learned, discipline in speech, conduct, and livelihood, great resolve and effort, and concentration.

Not only is thought an inescapable ingredient in all action; it is necessary to man’s salvation, for, as we have observed, man is born indeterminate, and salvation is not automatic. Some guide is needed, over and beyond the dispositions of the plastic body and the idiosyncrasies of culture. Buddhism is aware of this condition of man. There are no supernatural gods, a priori principles, or pre-existent, permanent souls on which man might, in his extremity, rely. But there is an observable psychic law of cause and effect; and there is the power of man’s thought, whereby man determines who he is, what his world is, and whether he suffers hell or enjoys bliss. But thought (presumably the Buddhists here mean to include unconscious thought, or imagery) guides action; and since only positive action can neutralise negative actions, a change in man’s thought is the one thing needful. In a similar way, man’s emotions must be changed by 7

him, that is, by his own thought. For hatred does not cease by inert passivity any more than it ceases by hatred; it ceases by love, and love arises out of man’s truthful relation to his world. Buddhism’s emphasis on understanding may seem like a truism until one considers the vast numbers of people who labour under superstition and have never moved out of its half-light to face, progressively, the emergent truth about themselves and their world. They blindly and passionately pursue their objects and goals; they toil at their tasks with the brute patience of a bullock harnessed to a well wheel; and they become blind to the puniness, precariousness. and impermanency of their lives and objects of satisfaction. “A social system,” said Whitehead, “is kept together by the blind force of instinctive actions, and of instinctive emotions clustered around habits and prejudices.”

To understand this fact, in the Buddhist sense, is to be lifted above the level of the brute, and initiate a transformation that leads to liberation. Most of the time the mass of us live under the spell of the immediate, appetitive, and sensate, as if what is and has value for us always has been and always must be. We will fight to keep what we have; and if we have surplus time and energy, we may even go out of our way to impose our way of life on others. But to understand is to see that things are not thus necessitated. This misery, this suffering, this poverty, this oppression—they need not be! Things are everlastingly changing; it is man who saddles them with habit and custom and so, blindly and tyrannically, destroys himself and others. But as man has made himself, so he can, by unmaking himself, re-make himself.

By the intellectual realisation of this truth, with its hope, man can begin to get out from under the burden of anxious compulsion, resignation and despair. He can acquire a sense of community with his fellow-men, and a sense of the possibility for human good. Neither social oppression nor personal unhappiness need to be; they can be undone and the blindness of animal passion and habit can be transcended. In the words of the Dhammapada, “The world does not know that we must all come to an end here; but those who know it, their quarrels cease at once.” Understanding has several aspects. It is, first, the perception of the world as flux and impermanence, and, with that, the realisation that suffering comes in consequence of our attachments to the impermanent. It is, second, the detachment that arises with that realisation— the release from the tyranny which our values exercise over us. The khandhas are essentially valuational processes, gripping or letting go of the world, and holding us in their grip so long as we identify ourselves with their processes and their products. To understand is to see, with detachment, that no single achievement, of ourselves, our families, our nations, our cultures, our race, is final, in fact or in value.

Some interpreters of Buddha and Buddhism are inclined to rest their interpretation there; in such cases Buddha’s lesson is at best a negative one. But beyond these meanings there is yet another, if only implicit in Buddha’s teachings. That is not merely what E. A. Burtta calls “continuity of moral growth toward liberated integrity,” though it includes and presupposes that. It is a whole-hearted commitment to a way of life that is characterised by continuous and progressive transformation, of understanding, surrender, courage, and compassion. It involves detachment from specific goods but also an appreciation of the unique particularity of each good as it appears. This is the whole doctrine of “enjoyment without possession” lifted to its height. Understanding has its own value and power; but beyond that it fully humanises us by releasing our emotional, active, and social powers from the dominations and dependencies of the world and enabling us to live richly through time with strength and joy.

Understanding requires a kind of resolute renunciation of itself. It must be touched by what the Ch’an masters called cultivation through non-cultivation. The intellect must not take itself too seriously. It must be sobered and softened by the realisation that underneath all metaphysical or religious solemnity there is the sportive, child-like play of things; and that 8

behind every square corner in the geometric world of the intellect, lurks the imp of particularity to upset every cart of a System. Yet often more than one “nasty little fact” (as Thomas Huxley put it) is needed to destroy “a beautiful theory” or a social system; an intellectual or social revolution may be required. We lead ourselves into traps of our own making because of our tendency to form stimulus-response bonds; and this tendency to habit gets ratified and fixed by the response of the intellect. Habits of body and of mind entrap us because they blind us to the unique quality of goodness inherent in every person, thing, and situation. Whitehead’s advice, “Seek simplicity (of abstractions), but distrust it,” finds-favour with a Buddhist. For the Buddhist is a nominalist, and with Husserl cries, “To the things themselves!” Indeed, a Buddhist is only a nominalist “in name,” for while we may name things, things are not the final realities. How effective might man’s mind become, and how happy might man be, if he could form the habit that would free him from the tyranny of habituation. For may we not ask ourselves:

What remains after our emotional habits of distress, ill-temper, anxiety, and the rest have spent the greater part of our energies, and we have ground away our intellectual lives in the groove of wasteful habit? Understanding alone is not sufficient for liberation; as Gotama said, we must detach ourselves from detachment itself. We must be liberated from the repetitiveness of habit, which easily uses up our powers to respond sensitively and creatively. We must open ourselves to the forces of rejuvenation. We must cease taking the recurrent trifles of life seriously, and not consider that every cross-road is a major crisis. Our attachment needs must be to something deeper than the customary, the familiar, the established, and the known. It must be to those uncompelling leaves of grass that spring up between our feet as we walk. We must, as William Ernest Hocking has said, “combine an unlimited attachment with an unlimited detachment”.

(2) This means that a second response man must make for his deliverance is renunciation. Renunciation occurs in the act of understanding. For understanding is an ascesis of awareness; it is a disciplining of our responses by the free manipulation and ordering of terms and symbols. It is the intellectual cleansing that produces moral integrity. When we understand we renounce the impulsive and the utilitarian attitudes toward things; we renounce the immediate and the technical for what is abiding and is an end in itself.

Specifically, what is renounced is sensuous attachment to the world (and hence to our “selves”), malice toward others, and our tendency to do harm to others. Is our love of the world so great that we can renounce it in order that the world might return to us, as the Gita puts it, in a transfigured way? Anyone who doubts that man’s pride in his sensuous enjoyments and possessions hardens his heart as a miser’s heart is hardened by his greed for his gold, and thus destroys that tenderness and plasticity needed for creative relations with others—anyone who doubts that should observe the world today.

Many of the leaders of the imperialistic nations and evangelistic religions of the West, and many of the land lords, owners, and local authorities in Asia and Africa, are so obsessed with the threat of their loss of power that they cannot see clearly the situation that confronts them or the things they must do in order to deal with it and to be saved. They are blinded by the diffuse reactions of a deep anxiety—anxiety that stems from their attachment to their power, their satisfactions, their structure of beliefs, in a word, their whole way of life, and from an awareness that these values might be impaired or removed. They cannot adjust to change, let alone promote change, because they have staked their lives on the status quo.

There was a time when egoism was relatively harmless. Prior to the age of technological and industrial power, the roots of the self could not sink very deeply or widely into human affairs. The harm of ego-involvement was limited to the range of materials and of culture which the ego 9

could command. But now a man’s “world” may be very wide. A Hitler or Krupp, a Hearst or Rockefeller, can exercise control over millions: his word is their law, because the tentacles of his self and his world reach down into their lives and enwrap them like giant vines in a tropical forest. In this way the egoistic values of one man or a few men are imposed on a multitude, and in this way tenacious attachment to the ego can lead to mischief and disaster on a wide scale.

The evil that such men do is not merely the blind execution of the demands of some “system.” Systems operate through individuals. To be sure, the system of imperialism is a set of exploitive relations: but it is only because men willingly or blindly submit themselves to those relations that the system continues. And that submission is possible because men do not understand their situation as human beings and cannot renounce the egoistic values to which they desperately cling. Such desperation is born of anxiety and panic, and is akin to the desperation of a man who, in his haste to get into a life boat, drowns his fellow-passengers as well as himself.

For certain persons to renounce their established values of capitalism, colonialism, white superiority, economic and military exploitation, and all the rest, would be to renounce their very gods. But they cannot, because they have invested too much of their lives in worship at the shrine of those gods, and they love them too dearly. The recent battle-cries of the West—“get tough,” “massive retaliation,” “operation killer,” “war of extermination,” “positions of overwhelming strength”—express the arrogance of certain people bent on defending and imposing their own values as well as their desperation in the face of a threat to those. Marx observed that successful and oppressing classes always blindly and violently defend what they have and are: they have become smitten by the power of their golden calves. But the oppressed class has nothing to lose but its chains, and because its temptations and attachments are fewer it is apt to be more realistic and more disposed to relinquish the values of the present in favour of something greater in the future. Yet the oppressed class is possessed by a passion too, different in expression but similar in origin to that of the oppressors.

A deprived man, once he has had a glimpse or a taste of goods, is apt to be overcome by hatred, indignation, contempt, envy, anger, and vengeance toward the ruling class. These attitudes are not evil in so far as they issue in action which rights wrongs; but they tend to become evil by a distortion of the power and the understanding which a man might wield. There is some indication that the social transformations now being wrought in Asia have been carried forward by men and women more realistic and less violent than those who conducted western revolutions. One of the reasons for this, I think, is the emphasis on detachment and renunciation propagated by Buddhism. Personal animosity, springing from oppression, and focussed on specific persons, is not as effective as an intelligent understanding of the long-range causes and consequences of man’s actions in history, and a diligent attempt with others to correct the causes of oppression. Personal animosity thus focussed wastes one’s fire and blinds one to the basic task that is to be done.

There is, moreover, the ever-present human problem: how may we all live most effectively once the wide gap between the haves and the have-nots is bridged. All of us are tempted to live by the world we “have” (be it expressed in tangible goods or the symbols of the psyche) rather than by the process of creative growth bringing with it the advance of understanding, mastery, and fellow-feeling. Failing to do so, we find the tables turned, and the world we have then has us. Never has the problem of possession and renunciation been so urgent as it is today; for as the domain of human wealth increases, men are more insistently forced to choose between freedom and suicide. Many Americans are sick with a satiety of goods, physical and mental; they refuse to be selective; they have, as Alan Watts says, a kind of 10

omnivorous attitude toward the world: consumers and nothing more. They had best go back to their ancestor, Thoreau, who knew how to choose, reject, and simplify—who knew that the way to inner strength is renunciation and freedom from all that the world can give or take away. I read the other day of a wealthy American woman who took her own life and those of her children because, as she wrote, she was “second to TV and comic books.”

She is symbolic of the suicide that a whole nation can bring upon itself when it cannot renounce its wealth and control its leisure. So, also, are the many delinquents, criminals, neurotics, and psychotics of this and certain other wealthy lands. People will cheat, rob and kill in an economy of abundance. While such crimes are sharpened by the insecurities of local and world economies, they are also the consequences of a spiritual failure in the minds and hearts of men. The triumph of “property values” over “human values” does not mean that we must scorn materialistic advance, but it does mean that we will destroy ourselves with such advance if we are not prepared to produce and control material values for the benefit of what is best in human beings.

It may be asked, “What about the great mass of the world’s population, who know only deprivation? Surely their problem is not renunciation.” Their problem is and always will be renunciation, which is an integral aspect of human fulfilment. For they cannot achieve fulfilment if in the process of liberating themselves from physical poverty, starvation, and disease, they only fall victim on the other side to the depredations of accedie, greed, vanity, covetousness, violence, and all the other ’civilised’ illnesses that beset modern, industrialised man. What about over-population? Is it not produced by ignorance, lust, and an unbridled attachment to the appetites?

What about prejudice? What about violent racism, religion, and nationalism? While certainly influenced by man’s physical environs, these are problems that are recurrently human ones, arising from man’s outlook upon himself and his world, and they cannot be settled until man settles himself. Whether man is rich or poor, skilled or unskilled, educated or ignorant, well or ill, his problem is always uniquely this: how to manage his will in relation to what he has or does not have. Every man, if he would be a man, must be able to sweat it out, like the gods of earth, and to laugh, like the distant gods. Is it so strange that in explaining renunciation Buddhism has coupled malevolence and harm to others with attachment to sensuous things? He who loves his world and his self over-much always strives to keep it intact. He resists and resents its breakage, or the threat of its breakage. This entails a resistance to the transforming influences of the world, both consciously known and unconsciously felt. The egoist loves his status quo.

Because this attachment prevents him from seeing that he could in fact open the way to much greater good for himself and others if he would renounce it, it also prevents him from creatively relating himself in sympathetic, appreciative, and cooperative ways to others. But the egoist is not just isolated. The very presence of others, vaguely apprehended, is a threat to him. Therefore in his unconscious compulsion to relieve his anxiety and protect his interests, he feels an urge to eliminate the gulf which separates him from others, and may do so by techniques of domination or submission. Differences are always a threat to the egoist, and he deals with them by attempts to obliterate them. This involves treating others as fragments, as types, as stereotypes, as lifeless members of classes, as things, as commodities, as means to one’s own ends. It involves ill will toward others. An egoist necessarily “rejoices in iniquity” and not in the truth because the truth arises and grows in the interchange of diverse particulars, and the communal source of truth is a threat to the egoist who claims to have the whole truth and who can secure himself in that conclusion only by denying or undermining the existence and the perspectives of others.

The total truth, in short, is the totality of mutually consistent, empirically correct perspectives, and we cannot really approach unto it unless we come to the realisation that our own perspective with its values is one among a multitude, and are able to view it with the renunciation that is born of a 11

detached mind and sane emotions. “If we think of our existence,” said C. W. Holmes, Jr., “not as that of a little god outside, but as that of a ganglion within, we have the infinite behind us.” When we give up speaking for or playing God, we can have the kindness of kinship with our fellow creatures; and the magnanimity of being one among (rather than over) many. If one has humility, is devoid of an overweening care for one’s own life, and genuinely respects oneself, then one can have the strength to care about others. But if one hates oneself so completely that one must abnegate oneself in order to be more than one, then one must also hate others and do harm to them. In this way renunciation leads to true conquest, and weakness, in the words of Taoism, leads to strength. This is a profound truth in Buddhism, developed in the Mahāyana tradition.

Psychologically, the status quo of a man is his established state of being; it is his “world” as he is able to feel, respond to, and find meaning in things. Our psychic “worlds” are the structures of belief and value selected out of our gross experiences by our sensitivities, needs, dispositions, and innumerable environmental factors. Thus what a man “is,” at a given moment, is this structure; he is indeed a complex of such structures, cumulative, and hierarchical. Western psychoanalysis and Hindu psychology have shown that man consists of many such layers, or “sheaths”, acquired by his experiences throughout time.

But man is something more than these established structures: he is at the core of such layers a dynamic of “becoming”, a continuous fountain of creativity which (in Bergson’s figure) is forever throwing off its products. Man’s “world” grows up around this dynamic centre and ever threatens to engulf it or to encase it in rigid walls; and so man, to retain his nature, must be vigilantly on guard against such self-strangulation. He must be always peeling away his created “worlds”, separating himself from the constrictive bonds of his past; and giving heed to that faint and tender voice of creativity in the depths of his many-levelled “worlds.” As Goethe said: “Would you live the happy way, keep the past out, of today.”

Egoism springs from a false belief in the permanence of one’s self, a belief that masks the fear of its downfall and dissolution. More accurately, egoism is the secret desire for permanence, and the realisation that this cannot be; and so the egoist, who seems so assured, is wrecked by this unresolved conflict. Precisely because he wishes to keep everything the egoist has nothing. But the opposite attitude is the relinquishment of one’s self-concept and cherished values as final; and this brings home to one more than one could possibly ask for or imagine. “The way to get, is to forget.” The honest facing of our transience carries us out of our egoistic illusions into bonds of fellowship which embrace us with a love in whose keeping transience seems acceptable, or unimportant.

One may ask: Does egoism spring from ignorance or from a deliberate refusal to acknowledge one’s own finitude? Is “the illusion of individuality”—as a modern psychiatrist, Harry Stack Sullivan, calls it—something that is inherent or acquired? We have been assuming implicitly that it is both, as Buddhists seem to do: man has tendencies which can be turned in the direction of rigidity and isolation, and his psychological, social, and ecological situation can be decisive in this turning. The logic of Buddhism precludes that man is born totally bad; for Buddhism holds that man can be saved from evil, and if he can be saved from evil then he must possess at birth both the materials and the means for salvation. What is it that comprises the goodness of the new-born baby?

It is the baby’s capacity for transformation by way of the increase of linkages of meaning generated between its responses and the things and persons around it; it is the baby’s capacity for continuous self-transcendence, for leaving, like the chambered nautilus, its “low-vaulted past,” for spiralling out into progressive identity with the vast universe of qualities. Man’s spirit, as Berkeley observed, moves, and, unlike those static perspectives to which it gives succession, cannot be perceived in the same way. The fabric of meanings woven on the moving loom of spirit is such that the strand which is my life is 12

inseparable from the strands that constitute other lives and existences; and sharp boundaries are obliterated. But faults and disruptions in the machinery of weaving may occur: the parent communicates to the child its own anxieties, hostilities, and conflicts; the youth senses the ambiguities and injustices of the economy in which he lives and must make a living. What is the result? Retreat, separation, crystallisation, individuality. The result is the isolationism and hidden terror which, in the Western world, reached its climax in World War II. The freezing of the spiritual fluids of love was thus described by W. H. Auden:

And the living nations wait,

Each sequestered in its hate

And the seas of pity lie

Locked and frozen in each eye.

In consequence of social orders which pit each against all and all against each—or, at best, pits the few against the many—men develop an unnatural concern with themselves. They “grasp” for particular securities instead of opening themselves to that one grand Security, that Supreme Identity, which can alone save. “Life is so short!” is our anguished cry, in this age of abundance and of promise of abundance. And when we experience sickness, injury, premature ageing, or the imminence of death, we are apt to protest, “Why me, why me?” Buddhism deals with this problem by turning the question around: if the meaning of life cannot be found in length of days, perhaps it lies in the death of the individual through his intellectual recognition of his transience and his emotional tenderness toward all suffering things. Life is, surely short, measured against the movement of sidereal or cosmic time; but physical time is only one dimension of that quality and the qualitative rapport we may have with one another. We probably do not discover this dimension in its fullest richness until we have been separated from our loved ones or nearest possessions; then it is, with the realisation of transience, that a deeper and freer love can possess us and woo and win us to its way of living.

In the place of clinging, therefore, Buddhism proposes to put the attitude of letting go; in the place of dominance, it proposes to put the attitude of non-interference. Such proposals are not mere dreamy idealism. There is a certain economy of nature that allows life to advance by the conditions of freedom and separation. The three factors that combine to produce progressive organic evolution, as Alfred E. Emerson has said, are “genetic variation, reproductive isolation, and natural selection.” Similar factors are required for advance at the psychological and sociological levels in the affairs of men. Novelty, solitude, and the selectivity of interaction are all necessary for human creativity. Novelty and solitude mean that we must let each other alone; and selectivity means that we must deal with them compassionately and considerately. This implies, too, that the U. N. principles of the self-determination of the nations and the noninterference by one nation in the internal affairs of another nation, are not abstractions but are rather rooted in the nature of human societies.

Renunciation arises from understanding, and understanding is confirmed in renunciation. To see one’s self as a temporary thing means to detach one’s deepest desires from the structure and aims of the self. Self-knowledge always leads to humility; it is disenchantment with what is all leaf and illusion, and a return to the root of reality. What is the alternative to this relinquishment of the illusory self? It is either resignation or mania. Men either “live lives of quiet desperation”, as Thoreau says, or they ride rough-shod over others and leave the wrecks and ruins of history behind them.

They either worship the external gods of a blind Nature, Fate, or Chance, or they create their own internal god out of their Self. But understanding can put in its proper perspective both the possibilities of the external situation and the limitations of man himself. Man is neither a passive pawn nor an autonomous king—his effective way is neither complete 13

dependence nor complete dominance. It is rather the middle way between these: a way that can seek without finding, desire without having, have without keeping, renounce without despairing, and understand without withdrawing. In this process man must give himself to the creative transformation if he is to be given unto; he must forgive himself and others if he is to receive forgiveness. To be able to live in the present and yet live above the present, to suck the juice from immediate fruits and yet see both the roots of the past and the seeds of the future, to acknowledge one’s presence and predicament in the world as important but not all-important: this is the most important thing. It is the meaning of intelligent renunciation, and it leads to the joy of nirvana.

Renunciation clears the ground for understanding. For it is our egoistic attachments which block our vision of what the world is and of who we are. “When a thing is not loved,” says Spinoza, “no quarrels will arise concerning it—no sadness will be felt if it perishes—no envy if it is possessed by another—no fear, no hatred, in short no disturbances of the mind.” Painprovoking attachments arise from our anxieties, and our anxieties force us into beliefs which momentarily allay the unrest of those anxieties but at the same time prevent us from the transformation that might eradicate that unrest. Thus we come to adopt and hold fast certain illusions: “idealised images” about ourselves, and an unduly glorified or darkened picture of the working of the universe. Our egoism, blinding us to ourselves and to things, makes us prone to believe that stock of popular superstitions which impinges on us from all sides from birth to death.

In this way our basic anxiety takes, as Epicurus observed, two fundamental forms: the fear of death, and the fear of the retribution of the gods. Then we wander about in the cave of our ignorance, guided only by shadows, frightened by them, and unsure of their reality. Once, however, we renounce our overweening sense of importance, we are freed to open our eyes to what lies within us. The phantasms of private and public sources fall away like ghosts at dawn; the universe ceases to be peopled with anthropomorphisms; and the way is cleared for the liberating venture of seeking, and of finding. It is self-absorption which prevents this initial step in our liberation; and once the step is taken, then it is courage that is required to carry us along the pathway to fulfilment.

(3) A third attitude needful to man is resolution. This embraces the act of aspiration, purposiveness, and earnestness, on the one hand; and the determination of one’s destiny on the other. Man must be saved by his own efforts; he has none else as his refuge. If modern man is to have the Utopia of abundance and world peace which now beckons him from the future where atomic power will do all his physical labour, he must achieve that freedom and security for himself; no rulers, no parliament of man, no United Nations, no gods from on high, no act of fate, will present it to him on a silver platter. The actualization of such an ideal, moreover, will not come to pass apart from man’s wholehearted striving and unresting vigilance.

A steadfastness and stubbornness of what is known in the West as “faith” is called for. “Those who are in earnest do not die; those who are thoughtless are as if dead already.” Those brave and reassuring words of the Dhammapada have nerved the efforts of millions long before Goethe penned a similar sentiment in his Faust. To aspire in the right direction without wearying is the ultimate act that is required of man. What else could be asked? And “a good man” says Goethe, “in his dim urgency is still conscious of the right way.” Buddhism holds that this urgency must be enlightened and directed into right mindfulness and other disciplines of the eight-fold path.

To aspire earnestly and to determine one’s own destiny are entailed by both understanding and renunciation. To be willing to know, to face the brute propensity of possessiveness which lies at the base of our distorted natures, to analyse and resolve our habits into their constituent parts—this requires great courage and steadfast faith. In the same way renunciation is an act of courage, for it means abandoning one’s self and relinquishing one’s hold on cherished values. 14

One cannot fully grasp the moral implications, or the fervent hope of Buddhism, I think, unless one first understands the stark existential predicament of man which lies at the centre of its concern and thought. What is man? He is nothing. He may think he is something; but when carefully analysed everything that he thinks he is—fire-maker, tool-user, shaper of symbols, creator of culture, sublime intellect, immortal soul, son of God, Brahman Himself; or doctor, lawyer, merchant, thief, or John Q. Jones—he is not. For “nothing is but what is not.” Man’s myriad series of “selves” comes and goes, and no substantial thread binds the selves together; the pattern of karma alone endures. “Thou carriest them away as with a flood; they are as asleep.”

But while this is man’s extremity, puzzle, and tragedy, it is also his opportunity. Precisely because he is not bound to a permanent self bearing down on him oppressively from the past, man can and must make and re-make himself. In the interstices of becomings, man has the opportunity for re-directing the past and freeing himself from its blind thrust. Buddhist philosophy was consistent with the intent of Gotama when it developed the doctrine that a given event does not pre-exist in its causes, and the subtle doctrine of momentariness. From moment to moment we are different, and the success of life is to see this and make the most of it.

Not to see it is to be caught in the clutch of craving, habit, illusion, and suffering. The doctrine of momentariness is implicitly the doctrine of creativity. Gotama rejects the common-sense view of substance, which lends itself easily to the lazy and irresponsible religious notion of an immortal “soul-substance.” He also rejects the nihilistic view that things are utterly empty or illusory. What is illusory is the substantial appearance of events. (This is the point that Madhyamika philosophy has taken up and developed.) What is real is the qualitative creativity of experience—the nirvana to be appreciated in and through the passage of experience. Viewed in the dynamic span of the creative self, any given, achieved self is an abstraction. The substantive “I,” accordingly, cannot be real; it cannot really “pass through” an experience, for to pass through means to be affected and to be changed, but by definition such an “I” cannot change. The fact is that our selves become.

A child becomes an adult; the adult does not (contrary to Aristotle and others) pre-exist in the child. Similarly, a person becomes a mother by mothering, a farmer by farming, a writer by writing; the mother, the farmer, or the writer does not pre-exist and suddenly reveal himself. The self must be achieved, won, created. Anyone who has lived, i.e. has grown up progressively into new forms of reality, knows this. Earnestness is the moral attitude enjoined on us by the whole universe, since the whole universe in a sense is earnest. It is a popular saying that we should love people for what they are and respect them in their true being. But what is the being of man? Is it not that he forever changes and becomes, and that his character is the way he becomes—the energetic quality of his striving, in heart and mind, the courage and clarity of his aspiring, the depth of his compassion in helping others in their striving and aspiring? The courage to be is the courage to become. And this requires infinitely more courage than would be needed if our natures were already prepared and completed prior to experience. The emptiness of the universe is vast; and to fill our little portion of it with a creative act, moment after moment, and to find our immortality in that, is a large and noble task for finite man.

Creative becoming, as a norm for human life, represents an answer to David Hume’s proposition that we have no direct evidence for the existence of the world, the soul, or God, and Hume’s search for a guide to human life. Gotama’s analysis is very similar to Hume’s; and his answer is similar too; Kant, who was profoundly influenced by Hume, stated the nature of the self more clearly. The “self” or “soul” is only a regulative ideal, he maintained, for we have not lived out its full potentialities. We know it, as a dynamic process, only in part; it is forever becoming and incomplete. Moreover, the soul is an inner thing, hidden from sensuous perception.

Kant’s view moves in the same direction as Buddhist thought. Ultimate reality or value is not confinable to any given experience or achievement of the self. It is not a created structure but is instead a power of creation. In this sense it is “void”, non-sensuous, and indescribable. It is the source of our specific qualities, forms, values, and “selves”. Our suffering, therefore, lies in our ignorant, tenacious attachment to what is created; and our liberation, happiness, and fulfilment lie in living for that creative source: Salvation begins when we make the shift from one mode of orientation to the other. Sudden insight into the difference between these two modes is what Zen calls satori. To aspire for this kind of transformation and this kind of orientation is the highest aspiration one can undertake.

It would be impossible to re-capture or state the deep reaction of gratitude and hope with which people in India must have first received the message of Buddha. To learn that the miseries of life need not be; that one’s history or past could not doom one to eternal suffering; that regardless of one’s place or condition one could, by one’s own efforts and intelligence, achieve freedom: what a sense of liberation and hope this must have generated among vast numbers of people! Buddha’s was a call for resolute courage and self-reliance. It was a reaction against religion as an opiate of the people, and against all of man’s self-made opiates which permit corruption, parasitism, empty ritual, and superstition to flourish in religion and outside of religion.

Resolution entails understanding and renunciation. We cannot really live lives of courage unless we understand the ultimate issues of life and hold clearly in our vision the right path. Nor can our action be effectual unless we strip ourselves of useless impediments and run with patience the race that is set before us. Two-thirds of the world’s population live in hunger, poverty, and disease; the other third enjoy the abundance of modern technology and industry. Aside from its general emphasis on understanding and compassion, Buddhism lacks the socioeconomic perspective and method which can minister directly and curatively: to the problem of hunger, though it has been alleviative in its mental effects: But Buddhism has a profound insight relevant to the age of material abundance. For as Lewis Mumford has pointed out, man has become overmastered and mechanised by the multitude of material processes and things which his technology has produced. His means have become ends in themselves; and man, as an integrative, creative spirit, has ceased to be the centre of his personal life and his culture.

The cure for this is Thoreau’s simplify, simplify, simplify. This is a Buddhist principle, for to simplify means to renounce and to put first things first, to restore man’s attitude of self-mastery to the driver’s seat. The spirit of Gotama’s thought is that man ought to be the determiner of his destiny, so far as he can, and that to abdicate control of his life to kings, cartels, armies, editors, advertisers, pathogenic organisms, or any other force other than his own mind and spirit is slavery and needless suffering. This does not mean retirement from the world, nor does it mean mere action under the illusion that to act on one’s world is to be self-determining. It means rather that man must act resolutely to organise his life so as to increase progressively what he can think, feel, control, and communicate.

(4) A fourth attitude, already implied in the previous three, is Compassion. Understanding implies compassion, for to understand is to comprehend, to see suffering and mortality as the common condition of all, to be familiar with the family of living creatures. One cannot really and completely know all unless one knows that all are saved, and assist in that enterprise. Renunciation implies compassion too, for to give up one’s attachments means to open oneself to the multifarious needs and perspectives of the huge world-community. Resolution implies compassion, for one cannot seek to determine one’s own destiny and aspire to what is right without considering the tragedy and the struggle of innumerable others. The earnest man, purged of lust and self-seeking, surely cannot interfere with the lives of others; and at his purest 16

state, having helped himself, he will have the overflowing strength to help others. This is expressed in the magnificent Bodhisattva ideal of selfless love, “infinite compassion,” and “universal redemption.”

“At all costs I must bear the burdens of all beings … The whole world of living beings I must rescue, from the terrors of birth, of old age, of sickness, of death and rebirth, of all kinds of moral offence, of all states of woe, of the whole cycle of birth-and-death, of the jungle of false views, of the loss of wholesome dharmas, of the concomitants of ignorance— from all these terrors I must rescue all beings … And why? Because it is surely better that I alone should be in pain than that all these beings should fall into the states of woe … There has arisen in me the will to win all-knowledge, with all beings for its object, that is to say, for the purpose of setting free the entire world of beings.“

Compassion is the opposite of sensuous attachment and illusion, of craving and lust, ignorance and confusion. Compassion has a depth which carries it beyond the beguilements of surface appearance. In the same way that knowledge penetrates beneath the changing phenomena of things, and seeks to discover the real nature of things, so compassion seeks to go below the level of smiles or tears which people may wear, the masks of position and repute which are taken as real by so many, the characters which they have built, the habits which dominate them, the desires which determine their habits, and, ultimately, the potential means of their liberation.

Compassion is a fellow-feeling for the plight and possibilities which we share with others. Such a feeling is not mere sympathy; it is sympathy qualified by a positive sense of clear distance between ourselves and others; it is what Nietzsche called “the pathos of distance.” Compassion is impossible unless we ourselves have been purified of egocentric drives and obsessive cravings: otherwise what passes as compassion is only an attempt on the part of the self to embrace, dominate, and swallow up the object of our interest. Compassion then is mistaken for what is only the extension of the ego’s needs; the object of interest is not seen for what it is, in itself, as a living, suffering, and striving subject; it is not seen with genuine “respect” but becomes only an item in a perceptual field to be organised and used. Compassion of that kind is only the velvet glove for the iron hand or the acquisitive palm. This is why “love,” in the West, has been called “blind;” it is passion and lust, devoid of the detachment which can emerge only when we have conquered our own desires and freed ourselves from the distortions in knowledge caused by coercive needs.

Compassion begins at home. “Let each man first direct himself to what is proper, then let him teach others.” To reverse this is to have the blind leading the blind. When we grow in our own integrity to a greatness and magnanimity of soul; when we can scorn personal injury and death as incidents in the destined progression of man; when we can cast off the fetters of fear and hatred of our enemies; when we shed like a heavy burden the unmet demands we make upon others and the world, and are able to have all that is worth having because we want nothing; when we live in each moment grateful for its blessings and responsive to the unmerited wealth of value left in the wake of time as it passes: then we are truly free, and are able to discover others and help them because we have first discovered and helped ourselves. This is something which our “other-directed” cultures tend to forget.

Compassion begins in solitude—in that “sweetness of solitude” that is the distillation of inner victory. “We must be our own,” says Emerson, “before we can be another’s.” Compassion arises out of a clarified trust of one individual for another. But man is a huddling animal. He huddles, not because he is solitary, like some animals, but because he is lonely. Loneliness is the felt isolation from the object of some desire; and man, being conscious, is able to desire many things —the moon, the sun, the cosmos, and eternal life—and hence to experience deep loneliness. The 17 pathology of human life is to be seen in man’s efforts to overcome this loneliness; and most of those efforts are social. Man seeks to exact recompense from his fellows. He believes not only that the world owes him a living, but also that it should provide for him a cure for his loneliness. So he forces himself into communion with others, and gains a vague sense of assurance there. But as loneliness arises in the self it must find its essential cure in the self. While the self takes its origin and data from a social context, it is also, on the other side, a solitary thing.

What we do, what we think, what we become, are consequences of personal acts. After we have received the insights of a providential grace, the ultimate decisions are ours alone to make; the ultimate freedom is ours alone to fashion. And these decisions, this creative freedom, must be achieved in solitude. When this is accomplished, then we can see others for what they are and can see the loveliness that lies in them. This clear-eyed perceptiveness, from which the subtleties of exploitation have been expunged, carries us then on to compassion. A vast majority of men live under the dominance of food, sex, other material goods, and money. This is true in Los Angeles no less than in Lucknow. It is a fact which ruling economic groups, politicians, advertisers, and charlatans of various kinds universally recognise and tend to exploit for their own selfish ends. But we could not be victimised by others if we were not first our own victims. Men are lured and betrayed by gold and pleasures, by social power and arms, because in the first instance they set up and assert those values. Such traps are of their own making; and it requires both predator and prey to spring the trap. A sociologist of knowledge, however, might say that man is not entirely made by his own habits or decisions, since these are influenced by his social context; and that is a truth that needs to be added to Buddhism.

At the same time, it is men who help to make their social context. Compassion is the opposite of self-indulgence. It should be distinguished from the mystical feeling which one may have in being identified with a family, a nation, a culture, or a mob. Such exaltations or phobias are a far cry from genuine sympathy. They are egoistic sentiments expanded, projected, and glorified on a social scale. One does not really see or understand others as individuals: what one sees is one’s own inner world, filled with needs and ideals, and one then gives oneself the illusion of objectivity and charity. Indeed, it is necessary for men driven by cravings to seek this sort of security; any other sort they could not tolerate. The egoist is devoted to the status quo; he could not bear to have it broken down by the intrusion of other personalities with their problems. This is why, as Dr. Elsa A. Whalley has recently discovered, gregarious and active persons who take a ”live and let live” attitude are often “inflexible at the core.” Their many social contacts and gay camaraderie are only false fronts for an unregenerate individualism.

We cannot exercise compassion until this self-concern is broken; we cannot give ourselves to others until we first have given up ourselves. The story of Kisā Gotamī illustrates this. When we weep at the passing of others, do we not weep for ourselves, or a portion of ourselves? Yet this kind of painful separation of the self from itself is a recurrent thing that has no cessation. “Decay is inherent in all compound things.” We may, however, reply: “No, I weep for life that might have been, that might have enjoyed itself, that might have grown up and fulfilled itself.” Even so death is a final fact from which there is no reprieve. The past is done, and the present ever presses upon us and presents itself before us, as a continuing gift.

The only satisfying response to death is to lose oneself in a new life—to find, as Kisā Gotamī did, an end of sorrow through an open-heartedness to all her fellow-sufferers, whereby her own private grief is transformed into deeper understanding. More sacrificial renunciation, braver resolution, and broader compassion. The only effective way to cope with individual disappointment, diminution, and death is to find new affirmations; for death is not overcome by mourning anymore than hatred is overcome by hatred—it is overcome by life and by love. If one’s child dies, one must find new children,now living, who need the ministrations of a humble, wise, and compassionate heart. If 18 one’s self and its ideals, loyalties, and attachments die, as indeed they must, one must find another self, chastened by the lesson that what is deeper and more dear than any individual self is the process that progressively transforms the self toward new levels of integrity in understanding, power, sympathy, courage, and faith. In this process, in time, one may find a qualitative peace and assurance that endures through time.

Buddhism is not simply a religion of compassion. For its compassion is not ignorant, passive, or selfish, but is guided by understanding, carried out by earnest action, and directed toward all sentient creatures. Buddhism is just the opposite of self-indulgence; and if anyone believes that man is “naturally selfish,” he should consider how Buddhism over a period of 2,500 years has profoundly influenced millions of people. Self-indulgence has two sides, apathy and licence, and Buddhism opposes the first by its emphasis on “receptivity and sympathetic concern,” and the second by its “self-control.” Both of these attitudes involve understanding and renunciation. Some Buddhists have stressed the first attitude (the Bodhisattva ideal) and others the second (the Arahatta ideal). Thus Buddhism is simple in that it comes to grip with the basic, recurrent tendencies and attitudes of human nature: but it is complex because it considers that one must counter dependence with the attitudes of understanding and resolute action; dominance, with the attitude of non-interference or renunciation; and detachment, with the attitude or compassion.

All of these attitudes, along with their opposites, must, in Buddhism, be transcended by the Maitreyan ideal, described by Charles Morris as “detached-attachment:” one must live within, but rise beyond, all bonds, all cravings, all thoughts; one must find liberation in and through the creative transformation of experienced qualities. This is the whole meaning of “the middle way” and its consequence and reward, Nibbāna. Conclusion

Buddhism has shaped the lives of countless millions through the centuries because what people need is compassion; they need to give it no less than to receive it, for unless we can receive it we cannot achieve the self-acceptance of maturity, with its full capacity to feel, think, and act; and unless we can give it we cannot know the full significance of a life devoted to something higher than itself. In referring to this lesson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., has said that a man “may put it in the theological form of justification by faith or in the philosophical one of the continuity of the universe. I care not very much for the form if in some way he has learned that he cannot set himself over against the universe as a rival god, to criticise it, or to shake his fist at the skies, but that his meaning is its meaning, his only worth is as apart of it, as a humble instrument of the universal power.” Compassion, cleansed of provincialism and the drive for power, gives man a sense of such super-personal participation.

Indeed, it may be questioned whether without an initiating and continuing sense of compassion man may rise to any worthy philosophy, religion, or heroism at all. For compassion is the most intimate and primary binding power which we can experience; if we cannot feel a sense of at-oneness with our fellow beings, surely we cannot feel the same toward the universe. And, conversely, communion with our kind radiates out into every detail of our experience and communicates its assurance and good feeling to the whole of history, the creatures of nature, and the universe itself. This sense is very powerful in the full flowering of Buddhism. More important, Buddhism has realised only implicitly that man is more than what he thinks, that his thought cannot be the only thing therefore that will save him, and that unconscious powers lying below and beyond the reach of his conscious mind (in the psyche and society) must continuously transform his conscious mind to release it from its limitations and from the suffering which man undergoes when he lives by its structures. Buddhism 19

acknowledges the ultimate fact of change; it conceives of its problem as that of breaking the grip of the causal series which forms our self and the apperceptive world. This is to be accomplished by knowledge, conduct, and concentration.

Suffering itself is an experience that comes to us and stimulates us to change, in spite of our conscious efforts to prevent it; and we cannot cope with it completely, once it has come, by mere understanding, resolution, or any other conscious attitude. Indeed, to explain the transformation in the lives of many Buddhists we should have to look below the level of conscious belief to a creative power into whose keeping these persons were led to give themselves, and which led to a qualitative poise in passage that no mere belief could generate. The Buddhist emphasis on renunciation of all clingings would carry a person part of the way in that self-giving, but it does not indicate explicitly the positive creativity that easily transforms man once the grip of his devotion upon created form has been relinquished and other conditions have been provided.