The consciousness collection

Many people think that we ARE consciousness or that our minds are consciousness. So we need to try and discover what consciousness is and how it operates.

Consciousness can be defined as the ability to be aware of something. It can also be thought of as our ability to recognize objects of the "outside" and "inside" world. So, what are the objects that we are aware of?

First is forms. This includes the sights, sounds, smells, tastes and tangible objects in the world around us. This also includes the sights, sounds, smells, tastes and touch of our own bodies.

Then there is consciousness of mental objects. This includes awareness of our thoughts, feelings, perceptions, Intentions or ambitions, and even awareness of consciousness itself.

Our awareness of a visible object needs several things in order for that awareness to occur. First we need the object, then we need the physical organ of the eye. Finally we need the link with consciousness in order for us to become aware of the object.

If a book is placed in front of a blind person, they will not see it. If someone is in the room with healthy eyes, they may see the book, but only if they look in the book's direction. Finally, they may look in the book's direction, but if their awareness is focussed on something else, like the meeting that they're going to have this afternoon, then even though the object is there, the eye is working properly, and we are looking in the direction of the book, the book is not "seen" because consciousness has not made the link between the mind, the eye, and the object.

Sometimes we may feel that we are aware of the book even though we aren't looking in its direction. However, this is based on having seen the book in the past and assuming that it's still there. If someone took the book while we weren't watching, our assumption would then be mistaken. We would act as if the book were still there. In this situation, this isn't a big problem, but under some circumstances, such as where we assume our children are in the house, accidents can happen and harm can result. This is also how assumptions affect our awareness.

The same holds true for the ear and sounds, the nose and smells, the tongue and tastes, and the body and tangible objects. It is even true for the mind and ideas. This is part of what accounts for the many differences in perception from one person to another. And we have yet to get involved in the effects of the preferences and biases of each person.

Out of our contacts with objects of these 6 senses comes feelings. We relate to things as positive, negative, or neutral. This starts out as like, dislike, and neutrality. Through attachment, these can become greed, hatred, and indifference. These emotions will also affect our awareness. Again, we can even be so preoccupied as to not clearly recognize what feeling we are having during a particular contact or we can detach ourselves from the whole process of feeling and sensation altogether. Another possibility after that is to misinterpret, or reinterpret, the feelings that we are experiencing thereby altering our perception and our awareness of the qualities of an object or situation.

Besides this, all of our goals and ambitions, and our views of the world around us, influence our ability to perceive and alters how we interpret what appears to our consciousness from all of these sources. Our likes and dislikes then become influenced by our goals and ambitions and our view of the world. From there, we tend to be focus on and pay attention to what we like, avoid or resist being aware of what we don't like, and ignore what we are indifferent to. This is how our intentions influence our perceptions and feelings and then help to determine what we are aware of and how we interpret it.

Not all of our experience is under our own control. Some of the impressions and views of the world that we carry with us are the result of the things that we have experienced, good or bad. The most important aspect of this, from the point of view of our spirit, is how we view and interpret, what has happened to us.

In the case of someone who has experienced a traumatic event. They need to recognize the role of others and the faults of others that helped to create their experience.

We need to recognize that others are human and cause harm because of their own desires, frustrations, fears, and ignorance. This is similar to the time when we realize that our parents aren't all-knowing gods, but just people like everyone else. Recognizing the fallibility of others and the affect these fallible people have on our lives is important.

We often subconsciously feel that what we experience is totally up to us, but others, who are not necessarily out to help us, also have an impact. We are not in absolute control of everything that happens to us. This is part of what we need to understand in order to help heal our trauma.

It also helps to recognize that we can't change the past and that all we can do is take whatever lessons we can from the situation and put the experience behind us and let go. That letting go may involve forgiveness of the others involved or, at the very least, understanding of their fallibility and human-ness and imperfection.

From all of this, we should recognize that it's impossible for consciousness to work on its own and there are many things that influence our awareness. At least one of the other body/mind collections needs to be present. This means that form, feeling, perception, and intention must be present for consciousness to manifest and each one of these things will affect our level of consciousness.

This means that we cannot be JUST consciousness without something to be conscious of. Part of spiritual training is to become mindful of what is affecting our awareness and how our awareness is being affected by these things.

This involves our concept of what our mind is and one of the problems of the English language. In Tibetan, there are many words for the mind and different distinctions about types of mind.

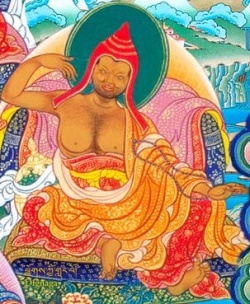

We tend to think of the mind as the brain. But the brain is really just a sixth sense organ. Its role is to store information and learning about our world. The brain remembers that "this is a square", "this is called a house", "that person's name is Jill" and these types of things. Buddhism calls that the secondary mind or "sem" in Tibetan. It is often called the discursive mind, or thinking, analyzing mind. It is placed within the Vajra family because of its link to structure, organization, differentiation, and logic.

Primary mind is basic awareness ("yid" in Tibetan). This is consciousness that is located at the heart centre. This consciousness, however, cannot exist on its own. When we die, we think that we give up our body and only mind continues after death. In this case, we are referring to this Primary Mind, but that description of the death process is not exactly accurate.

This is where our basic essence or "rigpa" comes into play. Our primary mind combined with a subtle energy wind is what makes up our basic essence. This is often referred to as subtle mind and illusory body. Our primary awareness is the subtle mind, and the subtle energy is our illusory body.

So when we die, we take a subtle energy body with us, after it has lost its connection to our gross physical body. In the in-between state, our attachment to and longing for gross physical existence and gross mental activities, leads us to seek out new birth. So, again, it isn't just consciousness that continues after death.

Another thing to be aware of is that consciousness itself is not permanent or stable. This is a perfect example of how the simile of the waterfall relates to what is happening to us within our reality.

In a waterfall, there are many droplets of water going over the cliff at the same time. Also, very quickly, they are replaced by new drops of water going over the cliff. The result is that the waterfall appears to be solid and unchanging.

The same is true of consciousness. We have sights, sounds, smells, tastes, touches, and ideas all happening together and vying for our attention simultaneously. Consciousness has to give some attention to these things within each microsecond in order to form a picture of the world around us. Then, just as quickly, the situation passes and something similar arises, so that consciousness is both kept extremely busy, and tricked into thinking that the objects around it and consciousness itself are solid, singular, and permanent.

Proof of these things is evident in tricks that animals use to hide from us and each other. Because consciousness recognizes differences more readily, many animals rely on camoflage for safety. Also, to save time and energy, consciousness tries to look for familiar patterns, and so some animals are coloured in ways that distort their shape so that it is difficult for consciousness to percieve that an animal is actually there.

This is also why many animals stay very still when they sense danger, because, quite often, consciousness will not perceive something if there is no change in what is being perceived. This is why, if you stare at a certain point for a long time, everything around it will seem to disappear. Many predators, such as Owls for example, will keep their eyes in motion and constantly move their head in an effort to refresh their impression of what is happening in their surroundings.

So what presents itself to our awareness and our level of awareness is constantly changing. What we focus on, and how strongly we focus also affects our awareness. When we are working on something intently or are working on something very interesting, we can lose track of time, forget our problems, and have the rest of the world disappear.

Not only that, but there are times when we have no awareness whatsoever. Examples of this are when we sleep and are not dreaming, when we faint or are put under anesthetics, and also at a certain point in the death process as we leave our bodies.

The reason that we awaken again in these situations is because of our habitual association with certain levels of awareness, our ties to awareness of certain forms and mental impressions, and the momentum for awareness that has been created by us in the past. This is why it is called our Consciousness Collection. We are a collection of consciousness moments and consciousness tendencies gathered in our past, having fruition and reinforcement in our present, and projecting new types and levels of consciousness into our future.

With shamata meditation, we become more aware of consciousness and also work to train our awareness. We begin by sitting still and not distracting our awareness with other activities. Then we watch our bodily sensations, thoughts, and feelings just to notice them and not act on them. The result is that we become more aware of what's happening in our body and mind.

This begins the practice of mindfulness. A very important teaching for Buddhists is called the four foundations of mindfulness. These are spelled out in the Satipatana Sutra and the MahaSatipatana Sutra (the Discourse on Mindfulness, and the Great Discourse on Mindfulness). It teaches us to become more aware of our bodies, our feelings, our minds, and all phenomena.

Through the process of mindfulness, we develop more deliberateness in everything that we do. We start by being very aware and deliberate in our physical actions, starting with in-breathing and out-breathing. We are told to watch ourselves and how we sit, stand, walk, and lie down. We practice being very aware and deliberate in reaching, and stretching, eating, and drinking, sleeping, and even urinating and defacating.

We are taught to pay attention to our feelings and to recognize where the suffering arises with them. The result is that we practice not allowing attachment, hatred, and indifference to accompany our feelings. For this, we have to pay attention to our feelings and then pay attention to how attachment, craving, and clinging become connected to them.

We are supposed to become aware of the changes in our perception, and to become aware of what goals and ambitions are behind our actions. This includes becoming deliberate even in the process of death and dying, using this process to heighten our awareness, contentment, patience, and compassion. We are also taught to become very deliberate in aiming ourselves towards a new rebirth. We are encouraged to deliberately aim towards either Buddhahood, a pure Buddha Realm, or a new human rebirth.

If we fully understand our BuddhaNature or basic essence, then, at death, we merely merge completely with that nature and attain Buddhahood.

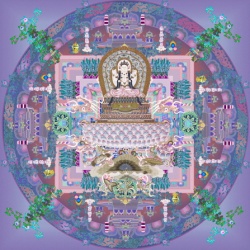

If not, then we can aim for birth in a pure Buddha Realm. A Buddha Realm is like a suburb of heaven. In a Buddha Realm, beings gather together to listen to Buddhist teachings, and discuss them. The difference between a Buddha Realm and other heavenly realms is that beings in the heavenly realms usually think that their existence in heaven is permanent, whereas beings in a Buddha Realm know that their existence there is temporary. They must again return to the human realm in order to finish their practice towards Buddhahood.

The final choice is to direct our consciousness and our energies towards a new human birth. If done well, we can be reborn in an place and surrounded by people where we can continue to strengthen our spiritual practice.

Finally, in that regard, we need to recognize our interconnection with others and the role that others play in influencing and developing our own awareness.

Others support our very existence and can either harm or strengthen our awareness and hinder or improve our level of awareness. They can distract us or pressure us to ignore certain things. They can also teach us to be more aware or to consider things that we hadn't thought of on our own. Within that environment, we need to become strong enough and view what we experience is such a way that our awareness is always being strengthened and improved. Without others we would not be able to learn about improvements to awareness or the extent of all of the problems arising from a lack of awareness.

We can also begin to work on improving the overall awareness of all beings and not just ourselves. This requires morality or the notion of not-harming. It requires patience and compassion.

We also need to recognize the fluidity of awareness and become masters at moving from one level of awareness to another, and from one object of focus to another. With practice, we can become relaxed and confidence in our use of consciousness.

In order for us to become relaxed, confident, and masterful in working with awareness, we need to eliminate clinging to our current types of awareness. It is clinging to our current awareness which is part of why we experience suffering, and why we have a difficult time extracting ourselves from some of our current problems. In order to change our view of the world, we need to recognize the limitations of our current view and look towards a healthier, happier, and more realistic, expansive and inclusive view of the world.

Through this process, we can become more deliberate in the use of our awareness, and because of that, experience less suffering now and in the future, have more control of our world, and be better able to help others in the process.