The nature of a buddha

The Buddha is presented to us as in certain respects simply a man: the sramat:ta or ascetic Gautama, the sage of the Sakya people. Yet at the same time he is presented as something much more than this: he was a buddha, an awakened one, the embodiment at a particular time and place of 'perfection', a Tathagata, one who comes and goes in accordance with the profoundest way of things. At this point we need to begin to consider more fully . what it is to be a buddha. I have already referred to a generally accepted Indian view of things that sees ordinary humanity, ordinary beings, as being born, dying, and being reborn continually.

This process is the round of rebirth known as sarrtsiira or 'wandering', and it is this that constitutes the universe. Beings wander through this vast endless universe attempting to find some permanent home, a place where they can feel at ease and secure. In the realms of the gods they find great joy, and in the worlds of hell great suffering, but their sojurn in these places is always temporary.

Nowhere in this universe is permanently secure; sooner or later, whatever the realrri of rebirth, a being will die to be reborn somewhere else. So the search for happiness and security within the round of rebirth never ends. And yet, according to the teaching of the Buddha, this does not mean that the search for happiness and security is futile and without end, for a buddha is precisely one who finds and follows the path to the end of suffering. Now the question of what happens to a buddha when he dies takes us to the heart of Buddhist philosophical thinking. Here Buddhist thought suggests that we must be very careful indeed about what we say, about how we use language, lest we become fooled.

The Buddha cannot be reborn in some new form of existence, for to exist is, by definition, to exist at some particular time and in some particular place and so be part of the unstable, shifting world of conditions. If we say that the Buddha exists, then the round of rebirth continues for the Buddha and the quest for an end to suffering has not been completed. On the other hand, to say that the Buddha simply does not exist is to suggest that the Buddhist quest for happiness amounts to nothing but the destruction of the individual being-something which is specifically denied in the texts.

Hence the strict doctrinal formulation of Buddhist texts is this: one cannot say that the Buddha exists after death, one cannot say that he does not exist, one cannot say that he both exists and does not exist, and one cannot say that he neither exists nor does not exist.33 One cannot say more here without beginning to explore certain other aspects of Buddhist metaphysics and ontology, and this I shall leave for later chapters. The important point is that a Buddha is understood as a being who has in some way transcended and gone beyond the round of rebirth. Be is a Tathagata, one who, in accordance with the profoundest way of things, has come 'thus' (tathii) and gone 'thus'.

So what does this transcendence imply about the final nature of a buddha? If one is thinking in categories dictated and shaped by the theologies of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and also modern Western thought, there is often a strong inclination to suppose that such a question should be answered in terms of the categories of human and divine: either the Buddha was basically a man or he was some kind of god, perhaps even God. 35 But something of an imaginative leap is required here, for these are not the categories of Indian or Buddhist thought. In the first place, according to the Buddhist view of things, the nature of beings is not eternally or absolutely fixed.

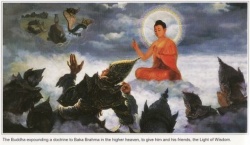

Beings that were once humans or animals may be reborn as gods; beings that were once gods may be reborn as animals or in hellish realms. Certainly, for the Buddhist tradition, the being who became buddha or awakened had been born a man, but equally that being is regarded as having spent many previous lives as a god. Yet in becoming a buddha he goes beyond such categories of being as human and divine. A story is told of how once a brahmin saw on the Buddha's footprints one of the thirty-two marks, wheels complete with a thousand spokes, with rims and hubs.36 He thought that such footprints could hardly be those of a human being and followed them. On catching up with the Buddha, he asked him whether he was a god or some kind of angel or demon.

The Buddha replied that he was none of these. The brahmin then asked if he was a human being. The Buddha replied that he was not. The brahmin was puzzled. So what was the Buddha? Just as a blue, red, or white lotus, born in water and grown up in water, having risen above the water stands unstained by water, even so do I, born in the world and grown up in the world, having overcome the world, dwell unstained by the world. Understand that I am a buddha. A buddha is thus a being sui generis: a buddha is just a buddha.37 But, in principle, according to Buddhist thought, any being can follow the path of developing the perfections over countless lives, and eventually become a buddha. That is, all beings have the potential to become buddhas.

Thus something has happened to Gautama the man that means that the categories that normally apply to beings no longer properly apply. Ordinarily a human being's behaviour will sometimes · be motivated by greed, hatred, and delusion and sometimes by such things as selflessness, friendliness, compassion, and wisdom. The different deeds, words, and thoughts of a being are an expression of these conflicting emotions and psychological forces. But for a buddha all this has changed. He has rooted out any sense of pride, attachment, or hostility. The thoughts, words, and deeds of a buddha are motivated only by generosity, loving kindness, and wisdom. A buddha can think, say, and do nothing that is not based on these. This is the effect or 'fruit' of what happened as he sat in meditation beneath the tree of awakening.

The bodies of the Buddha One early Buddhist text puts it that the Buddha is 'one whose body is Dharma, whose body is Brahma; who has become Dharma, who has become Brahma'.38 Now dharma and brahma are two technical terms pregnant with emotional and religious 'meaning. Among other things Dharma is 'the right way to behave', 'the perfect way to act'; hence it is also the teaching of the Buddha since by following the teaching of the Buddha one follows the path that ends in Dharma or perfect action.

We have already come across the term Brahma denoting a divine being (p. 24), but in Buddhist texts brahma is also used to denote or describe the qualities of such divine beings; thus brahma. conveys something of the sense of the English 'divine', something of the sense of 'holy' and something of the sense of 'perfection'. Like the English word 'body' the Sanskrit/Pali word kiiya means both a physical body and figuratively a collection or aggregate of something- as in 'a body of opinion'.

To say that the Buddha is dharma-kiiya means that he is at once the embodiment of Dharma and the collection or sum of all those qualitiesnon- attachment, loving kindness, wisdom, etc.-that constitute Dharma. Thus the nature of a buddha does not inhere primarily in his visible human body-it is not that which makes him a buddha-but in his perfected spiritual qualities. Another passage of the ancient texts relates how the monk Vakkali was lying seriously ill on his sick-bed; when the Buddha arrives Vakkali explains to him that, although he has no sense of failure in his conduct, he is troubled by the fact that because of his illness he has not been able to come and visit the Buddha.

The Buddha responds: 'Enough, Vakkali. What point is there in your seeing this decaying body? He who sees Dharma sees me; he who sees me sees Dharma.'39 This kind of thinking gives rise in developed Buddhist thought to various theories of 'the bodies of the Buddha'. Such theories are often presented as a distinguishing feature of later Mahayana Buddhism. This is misleading. Certainly, there is a rather sophisticated understanding of 'the three bodies' (trikiiya) of the Buddha worked out and expounded in the writings of the fourthcentury CE Indian Mahayanist thinker Asmiga ).

But this theory stands at the end of a process of development, and some conception of the bodies of the Buddha is common to all Buddhist thought. What is common is the distinguishing between the 'physical body' (rupa-kiiya) and the 'dharma-body'. The physical body is the body that one would see if one happened to meet the Buddha. Most people, most of the time, it seems, would see a man who looked and dressed much like any other Buddhist monk.

However, recalling the stories of the brahmins who examined the Buddha's body after his birth and the brahmin who followed his footprints, some people some of the time see-or perhaps, more precisely, experience-a body that is eighteen cubits in height and endowed with the thirtytwo marks of the great man as described in the Lakkha!Ja Sutta, 'the discourse on the marks of the great man'.40 This apparently extraordinary body appears in part to be connected with theories of the 'subtle body' developed in meditation. All this then is the physical body-the body as it appears to the senses.

The Dharmabody, as we have seen already, is the collection of perfect qualities that, as it were, constitute the 'personality' or psychological make-up of the Buddha. A Buddha's physical body and Dharma-body in a sense parallel and in a sense contrast with the physical and psychological make-up of other more ordinary beings. According to a classic Buddhist analysis that we shall have occasion to consider more fully below, any individual being's physical and psychological make-up comprises five groups of conditions and functions: a physical body normally endowed with five senses; feelings that are pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral; ideas and concepts; various desires and volitions; and self-consciousness. Any being might be considered as consisting in the accumulation of just these five 'heaps' or 'aggregates' (skandha/khandha) of physical and psychological conditions. And in this respect a buddha is no different. Yet a buddha has transformed these five into an expression and embodiment of Dharma.

Thus rather than, or as well as, consisting in the accumulation of these five aggregates, the psychological make-up of the Buddha might be considered as consisting in the accumulation of another set of five 'aggregates', namely, the various qualities of perfect conduct (sllalsfla), meditation (samadhi), wisdom (prajflalpaflfla), freedom (vimuktil vimutti), and knowledge and understanding ( vimukti-jnana-darsana/ vimutticilii!Ja- dassana ). Sravaka-buddhas, pratyeka-buddhas, and samyak-sambuddhas In this chapter we have seen how the Buddhist tradition regards a particular historical individual-Siddhartha Gautama-as an instance of a certain kind of rare and extraordinary being-a buddha.

Such a being having resolved to become a buddha by making a vow in the presence of some previous buddha of a far distant age, practises the perfections for countless lives and finally, born as a man, attains buddhahood by finding 'the path to the cessation of suffering'; he then goes on to teach this path to the cessation of suffering to others so that they may reach the same realization as he has done, so that they too may become 'awakened' or buddha. Both Gautama and those who come to realization by following his teachings-the arhats-may be referred to as 'buddhas' since both, by the rooting out of greed, hatred, and delusion, have come to understand suffering and the path to its cessation. And yet, as the tradition acknowledges, some difference between Gautama and the arhats must remain. Gautama, the Buddha, has found the path by his individual striving without the immediate help of an already awakened being and then gone on to show others the way.

His followers on the other hand may have come to precisely the same understanding and realization as Gautama but they have done so with the assistance of his unequalled abilities as teacher. We have then here two kinds of buddha: 'the perfectly, fully awakened one' (samyak-lsamma-sambuddha) like Gautama, and the arhat or 'one who has awakened as a disciple' (sravaka-1 savaka-buddha). Thus while on the one hand wishing to stress that the 'awakening' of Gautama and his 'awakened' disciples is the same, the Buddhist tradition has also been unable to resist the tendency to dwell on the superiority of Gautama's achievement.

Apart from becoming 'awakened' as a samyaksam-buddha or arhat, Buddhist texts also envisage a third possibility: that one might become awakened by one's unaided effort without hearing the teaching of a buddha and yet fail to teach others the way to awakening. Such a one is known as a 'solitary buddha' (pratyeka-1 pacceka-buddha ). The sense that the achievements of these three kinds of 'buddha' are at once the same but different-the Buddha's achievement being somehow superior-is a tension that lies at the heart of Buddhist thought and, as we shall see, explains in part certain later developments of Buddhist thought known as the Mahayana.

How does the Buddha's superiority to arhats and pratyekabuddhas manifest itself? In order to answer this question it is useful to return to a question raised earlier concerning the Buddha's nature as man or god. In the context especially of early Buddhism and Buddhism as practised today in Sri Lanka and South-East Asia, once it has been established that theoretically the Buddha is neither a god nor a 'Saviour', there has been a tendency amongst observers to conclude that the Buddha ought then to be seen by Buddhists as simply a man-as if this was the only alternative. A further conclusion is then drawn that, since Buddhism teaches that there is no 'saviour', the only way to 'salvation' must be through one's own unaided effort.

True, the Buddha did not create the world and he cannot simply 'save' us-and the Buddhist would say that it is not so much that the Buddha lacks the power as that the world is just not like that: no being could do such a thing. Yet although no saviour, the Buddha is still 'the teacher of gods and men, the unsurpassed trainer of unruly men'; in the Pali commentaries of fifth-century Sri Lanka he is often referred to as simply the Teacher (satthar). That is, we have here to do with a question of alternative religious imagery and metaphor: not the 'Father' or 'Saviour' of Judaism or Christianity, but the Teacher. If one is not familiar with the Indian cultural context it is easy to underestimate the potency of the image here. For a Buddhist no being can match the Buddha's abilities to teach and instruct in order to push beings gently towards the final truth of things.

A buddha may not be able to save us-that is, he cannot simply turn us into awakened beings-yet, if awakening is what we are intent on, the presence of a buddha is still our best hope. Indeed some contemporary Buddhists would suggest that it is no longer possible to reach awakening since conditions are now unpropitious; rather it is better to aspire to be reborn at the time of the next buddha or in a world where a buddha is now teaching so that one can hear the teachings directly from a buddha. For the Buddhist tradition, then, the Buddha is above all the great Teacher; it is his rediscovery of the path to the cessation of suffering and his teaching of that path that offers beings the possibility of following that path themselves.

As Teacher, then, the Buddha set in motion the wheel of Dharma. As a result of setting in motion the wheel of Dharma he established a community of accomplished disciples, the Sangha. In the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha the Buddhist thus has 'three jewels' (tri-ratna/ti-ratana) to which to go for refuge. Going to the three jewels for refuge is realized by the formal recitation of a threefold formula: 'To the Buddha I go for refuge; to the Dharma I go for refuge; to the Sangha I go for refuge.' Going to these three jewels for refuge is essentially what defines an individual as a Buddhist. Having considered the Buddha,let us now turn to consider his teaching and how that teaching is put into practice by those who take refuge in the three jewels.