Tibetan Religious Art

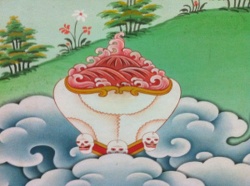

Most Tibetan art is religious art. The term "Tibetan art" encompasses art made not only in Tibet, but also that produced throughout the Tibetan cultural region, including Nepal, Kashmir, China, Mongolia, and Bhutan. Indeed, some of the finest examples of so-called "Tibetan art" come from these countries so deeply influenced by Tibetan religion and culture. The subjects of Tibetan religious art are typically Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, lamas, historical figures, and deities; mandalas, representing the abodes of the deities; stupas or reliquaries; and ritual implements for use in shrines and temples.

The vivid world portrayed in Tibetan religious art is filled with elaborate and esoteric symbolism and transcends our ordinary mundane perceptions. In Buddhist thought, all externals are said to be the display of the Buddha's body, speech, and mind. Religious art exemplifies the qualities and physical form of the Buddhas and deities (ishta-devata, yi dam). Art objects, therefore, must conform to the strict rules of iconography specified in Buddhist scripture regarding the proportions, shape, color, posture, gestures (mudra, phyag rgya), and other attributes in order to correctly depict a Buddha or other religious figure.

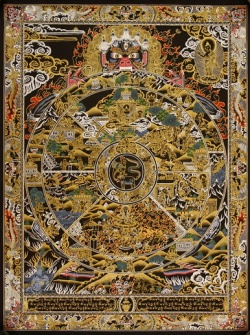

Such religious art can serve several functions. A particular art object can serve, for example, as a point upon which to focus in one's meditation practice; it can be a graphic representation of a deity or religious vision that appeared to a spiritual practitioner in a dream or during a session of meditation; it can serve as an icon, an object of reverence, or a medium through which a person may request a boon or the removal of obstacles such as sickness, poverty, or death; finally, an art object may serve as a teaching device used by a lama or monk to illustrate certain Buddhist doctrines, or as a central focus for public ceremonies.

The qualities of the Buddha are thought to be inherent to all sentient beings, but, unfortunately, they do not usually realize or understand this. In the attempt to internalize or actualize their innate Buddha-Nature (tathagata-garbha, de bzhin snying po), Buddhist practitioners try to visualize the deity actually appearing before them, or try to visualize themselves as being identical with the deity through meditation and focus on appropriate painted or sculpted images. Creating an image of the deity, whether in reality or meditatively, requires concentration on every detail. Hence, the act of producing a religious image, and even the act of gazing upon such an image, themselves become forms of meditation.

The outward appearance of the deities may vary, but their function of aiding the practitioner achieve enlightenment is constant. Different beings have different predominant afflictive emotions (klesha, nyon mongs) preventing them from realizing their true natures, and thus it is said that the Buddha manifested both peaceful and wrathful emanations in order to subdue the neuroses of various types of beings. Wrath itself, however, has no place in Buddhist teachings; the wrathful and furious divinities depicted in Buddhist art trample and burn away all vestiges of the "three poisons" (tri-visha, dug gsum), ignorance, anger, and lust. Their purpose is not to evoke responses of fear, but to free our perception from the constraints of ego-based emotions. Deities are sometimes shown with multiple arms, legs, and heads, portraying their enhanced ability to reach out and accomplish the aims of all sorts of beings. Overtly sexual images of union between male and female deities, very common in Tibetan art, are not, strictly speaking, meant to be regarded as sensual. Rather, they are symbolic of the union of wisdom (female) and compassion (male), the two indispensable qualities of enlightenment.

Inasmuch as the entire Buddhist world view revolves around the steadfast belief in karma and cyclic existence (samsara, 'khor ba), the processes by which one is helplessly and continually reborn in a succession of unsatisfactory lives, all Tibetan religious art may be said to address to the issues of death and human finitude. Specifically, paintings and statues depicting the perfected states of various Buddhas and Bodhisattvas who have transcended the sorrows of cyclic existence serve as ideal types to which the spiritually inclined may aspire; paintings evoking the "pure lands" or paradises of various Buddhas point to the possibility of a happier, more fulfilling existence for the religious practitioner after death; didactic paintings, such as the "Wheel of Life" (bhava-cakra, srid pa'i 'khor lo) on display here, graphically portray the diverse conditions in which sentient beings find themselves, explain the mechanics of cyclic existence, and suggest the possibility of becoming liberated from such circumstances; certain paintings expressly depict the variously pacific and violent visions said to occur in the intermediate period (antarabhava, bar do) between one's death and rebirth, the viewing of which prepares one to recognize such visions when they actually occur; images of furious "Protectors of the Doctrine" (dharmapala, chos skyong) adorned with bone ornaments and freshly flayed animal skins serve both as a reminder of the imminence of death, and as an inspiration to make the best use of the opportunities afforded by transitory human existence; and ritual implements and musical instruments are used in ceremonies designed to ward off obstacles and insure fortuitous circumstances for the recently deceased. Moreover, any form of an enlightened being may serve as a basis for offering (mchod rten), thereby enabling the faithful to accumulate merit and achieve a rebirth favorable to spiritual pursuits after death.