What is Dzogchen by John Myrdhin Reynolds

- The Dharma, the teachings of the Buddha regarding the nature of reality and one’s own true nature, were written down after his own time and now are found in three types of scripture:

- (1) The Sutras represent the public discourses of the Buddha on the topics of ethics, psychology, and philosophy. In terms of actual practice, this is embodied in the three-fold training in ethics, in psychology and meditation, and in philosophy.

- (2) The Tantras are more restricted and represent private teachings given to advanced practitioners, in particular referring to the methods of energy transformation and how energy manifests to consciousness. Here the emphasis is on Tantric sadhana or the process of transformation.

- (3) The Upadeshas are private advice on meditation practice given by a master to a disciple. Their principal concern is Mind, that is to say, the Nature of Mind. In Tibet, the Upadeshas are largely represented by Dzogchen and Mahamudra in China and Japan by Zen. All three systems of meditation represent non-gradual methods for the realization of sudden enlightenment.

- In Tibetan, Dzogchen means “the Great Perfection”. It is so-called because it transcends the Tantric transformation practices of the Generation Process (Kyerim) and the Perfection Process (Dzogrim). In Dzogchen everything is perfect and complete just as it is; nothing has to be transformed into something else as is the case with Tantra. It is called the Great Perfection because there is nothing lacking (dzogpa, perfection) and it is total with nothing higher or beyond it (chenpo, great). Basically Dzogchen signifies the state of contemplation beyond the mind, that is to say, just being in and finding oneself in that state. Whereas with meditation, the mind is still operating and mental processes continue to function, including the ego, but with contemplation, we find ourselves in a state beyond the mind, where the mental processes are no longer functioning in terms of the conditioning of awareness. Nevertheless, this is not unconsciousness because it is a state where we are totally present and aware. This contemplation is like the condition of the mirror that has the capacity to reflect whatever is set before it, whether beautiful or ugly. But whatever is reflected in the mirror in no way changes or modifies the nature of the mirror.

However, one must clearly distinguish the reflections from the mirror. In the same way, the Nature of Mind has the capacity to be aware of whatever may arise, yet these phenomena and thoughts whether good or bad, which arise to consciousness, in no way change or modify the Nature of Mind. So, in terms of Dzogchen, we must clearly distinguish between mind or the thought process and the Nature of Mind. Finding oneself in the Nature of Mind and its capacity for intrinsic awareness (Rigpa) is what is meant in the Dzogchen context by contemplation.

- The practitioner can access the state of contemplation through the practices of Zen, Dzogchen, and Mahamudra. However, Zen exists in the context of the Sutra system in terms of its explanations and source texts, whereas Dzogchen and Mahamudra come out of the context of the Tantric system and its processes for transformation. Both Dzogchen, which has reference to the Old Tantra system of the Nyingmapas, and Mahamudra has reference to the New Tantra system, especially of the Kagyudpas, represent the culmination stage of the Tantric process of transformation. However, both of them may be practiced on their own without first undergoing a prior process of Tantric transformation.

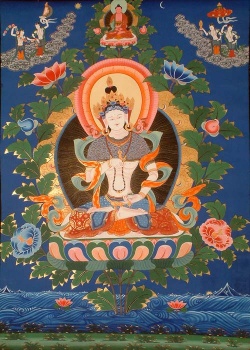

- Both Sutra, the philosophical system of Mahayana Buddhism, and Vinaya, the ordinations and monastic rules of the monks, were introduced into Central Tibet in the 8th cen. by the monk-scholar from India, Shantirakshita. His colleague, the famous Tantric master,Guru Padmasambhava, simultaneously introduced the Old Tantra system and Dzogchen into Tibet. The followers of Padmasambhava subsequently became known as the Nyingmapas or “the Ancient Ones” in contrast to the Sarmapa or Newer Schools of the Kadampa, the Sakyapa, the Kagyudpa, and the Gelugpa.

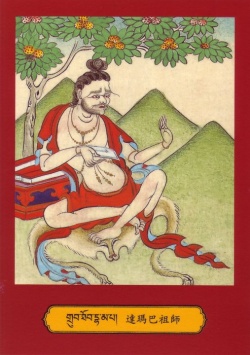

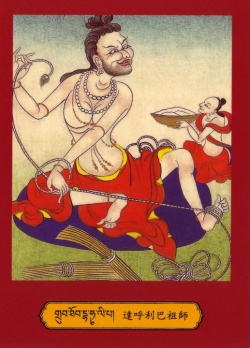

- The Dzogchen teaching is also found in the other old school in Tibet known as Bon. A practitioner of Bon is called a Bonpo. Although we find here much of the pre-Buddhist magic and shamanism that survived in Tibet, Bon also has the higher spiritual teachings of Sutra, Tantra, and Upadesha or Dzogchen. However, the principal difference between Bon and the other Buddhist schools is one of lineage and not of teaching. Bon traces its lineages back, not to Shakyamuni Buddha in Northern India 2500 years ago, but to another prehistoric Buddha who lived even earlier in Central Asia. He was named Tonpa Shenrab. In the 8th century, the Bonpo Dzogchen teachings were introduced into Tibet from Zhang-zhung by the masters Tapihritsa and Gyerpungpa.

- MATTER AND MIND

- In Buddhist perspective, there are three dimensions to our human existence traditionally called Body, Speech, and Mind. “Body” means our material body, the embodiment and encasement of our consciousness within a material vehicle moving about in the familiar physical world were we are engaged in the various activities of that world, especially in relation to other living beings also possessing material bodies. The Sutra discourses of the Buddha actually deal with all three of these dimensions of human existence, but the focus is on embodied consciousness, that is to say, our normal ordinary waking state of consciousness. The Sutra teachings are more concerned with this dimension of Body, especially our behavior and actions in terms of our interactions with other living beings. Therefore, there is much said here regarding ethics and morality and the rules of conduct that seek to prevent actions that would harm and cause pain to others. And the methods of the Sutras are often referred to as the path of renunciation.

But the Sutra system is actually concerned with our whole dimension of embodied existence. This particularly refers to our embodied consciousness, that is to say, our everyday state of waking consciousness where we find ourselves encased within a material body. Therefore, the type of psychology elucidated in the Sutras is more concerned with the surface of consciousness and we may say that this Abhidharma psychology, which developed out of the Sutras, represents a phenomenology of consciousness.

- The Tantra teachings, however, are much more concerned with energy and the transformations of energy. Therefore, the Tantra system is associated with our entire dimension of speech. Speech is sound and sound is energy and so Tantra refers to our whole dimension of energy as human beings. This means not only the sounds we make, but our breathing and our emotions as well. The word “Tantra” literally means continuity or continuum. What is continuous here is the emerging of energy in the form of thoughts and emotions out of the unconscious psyche. The term Tantra does not exclusively refer to sexual activity; sex is only one form of energy within human experience. Because of its emphasis on energy and sound, Tantra is also known as the Mantra system, where mantra is the creative power of sound and names to call phenomena into existence out of the pure potentiality of empty space.

In itself, energy is without form, but it may be given form by means of ritual, incantation, and visualization. Moreover, energy has the characteristic that it can change and transform, so the methods of Tantra are said to represent the path of transformation. However, here in Tantra, the concern is not just with the manifestations of energy, but with the deep hidden sources of psychic energy, namely, the Nature of Mind. This psychic energy pertains to what we usually call the psyche or the soul. Therefore, the type of psychology associated with the Tantras might be called Buddhist “depth psychology”, where the focus is on the depths rather than the surface of the stream of consciousness.

- However, the central concern of the Buddhist teachings is mind. Among these three dimensions of Body, Speech, and Mind, it is the latter that is most important and fundamental. Both bodily activity and the energy of the emotions depend on mind. Everything comes from mind. The Upadesha teachings of the Buddha and the Buddhist masters point directly to this mind that is the source. The focus of these instructions is the discovery within our immediate experience of this Nature of Mind and its capacity for awareness called Rigpa. The principal concern of both Dzogchen and Mahamudra is Mind, that is to say, the Nature of Mind. Here a crucial distinction is made between the mind (sems), our normal everyday thought process and waking state consciousness, and the Nature of Mind (sems-nyid), which is the source of our three dimensions of Body, Speech, and Mind. Our conscious thought process is changing from moment to moment; it is as fleeting as reflections seen on the surface of the water. But the Nature of Mind is outside and beyond time and conditioning.

This distinction may be illustrated by the example of the mirror and the reflections that appear in the mirror. The Nature of the Mind is like the mirror and the mind or thought process is like the ever-changing reflections appearing in the mirror. In our normal waking state consciousness, afflicted with constant distractions, we live in the condition of the reflections, whereas in the state of contemplation we find ourselves in the condition of the mirror.

- But in terms of meditation practice, it is easier to begin with the body, assuming a comfortable meditation position. Through asana (positions) and yantra (movements) we can control the body and make it immobile. In this way also, our energy and breathing can be controlled and made immobile employing pranayama (rhythmic breathing) and kumbhaka (holding the breath). Our body and our energy are easier to control than is the mind and both of them influence the mind. But among them, mind is the most important and the most fundamental. Everything comes from mind. So, what can be more important than mind?

- But what is mind? We tend to think in terms of dualities: mind vs. matter and spirit vs. nature. This brings to the fore many metaphysical questions where mind is opposed to matter and religious questions where Spirit is opposed to Nature. With meditation practice, however, we do not begin with philosophical conceptions and theories, scientific or otherwise, but with our immediate experience. Immediate experience is always the touchstone in Buddhism, not theory. Matter itself is an abstraction.

We infer its existence, but we do not sense or experience matter directly. It is not a direct perception. It is inferred and conceptualized and abstracted from our sense experience, especially from our eye-hand coordination. It represents a combination of sight and touch. If we see it and can touch it, we think that it is something real. But actually our sense experience is the datum, not the abstract concept we call “matter”.

- Similarly “mind” is an abstraction. What do we mean when we say “mind”? Or “I have a mind” or “Mr. Smith has a mind”? Does “mind” simply refer to the observed behavior of others? Do they act sentient and intelligent? In Tibetan, “sems” means mind and “sems-can” means a sentient being, that is to say, a living being that possesses a mind. A living thing or animal that moves in response to stimuli is inferred to have a mind. Trees and plants, although living things, do not do this and, so, they are said not to possess a mind (sems). Plants just like animals, however, possess life-force or vitality (srog).

- The Cartesian dualism of mind and matter has dominated our Western thinking for over three hundred years. We are told by our culture that we have a material body and that this body is like a machine. But then, where is the mind? Is it the ghost in the machine? Matter is thought to be something solid, real, and mechanical. Our culture provides us with a mechanical model of reality and causality. This model or paradigm has been the basis of modern science for three centuries and we are told that this model represents an accurate description of an external objective reality. Indeed, the procedures of modern science have provided us with an impressive technology, but providing us with a definitive and exhaustive description of reality is quite a different matter. But is this mechanism what we actually experience? Are we just computers made of meat?

- Buddhist philosophy is not afflicted with this radical dualism. Mind and matter are two sides of the same coin. Everything is part of a single continuous reality. But, of necessity, we may analyze out and abstract certain aspects of reality by way of our intellect. However, this does not make these distinct aspects separate realities or separate substances. Mind and matter are part of a single whole; they are not separate orders of being.

- In Buddhist terms, mind and matter are only phenomena or events (dharmas) that occur in the stream of consciousness of the individual. There occur here both mental and material events. These elementary events can be observed and brought into view by way of meditation practice. Meditation practice can slow down the processes of mind, which normally occur very rapidly in only fractions of a second, so that we can observe the operation of discrete mental processes. This is like putting a motion picture projector into slow motion.

Then through introspection or higher insight (vipashyana), we can observe at first hand how the mind works. The mental and physical events that occur in consciousness which comprise these processes can then be brought into view. This process of observation of the mind during meditation practice led to the development of Abhidharma psychology in the Buddhist tradition.

- Because these phenomena that we call “reality” can only be known and experienced by mind, what is more fundamental to our existence than mind? But what is mind? What does it do? Where is it located? We are not dealing with some explanation or theory, but looking inward directly at our immediate experience. Just look inward and observe what we sense and feel. What do we find? Where is this mind? Is this mind something material, a mechanism or an entity or a substance? Or is the mind immaterial and insubstantial? If it is something, an entity or a mechanism, then where is it located? If it is a thing, it must have a location. Is it a little black box inside of us like the scientists say?

Just look for this mind. Does it have a color or a shape? Is mind made out of something? If so, what is this mind stuff? Is it just the gray matter in the brain? Or is the mind just electro-chemical activity occurring in the brain and in the nervous system? Is the mind located inside the head, in our brain? Do we see our brain? Do we experience it directly? Electro-chemical activity—these are just words, but is that what we experience? Look at what we experience. Experience is always the touchstone. “Brain activity” is a concept and a theory, at best some readings on dials and graphs on a machine in a hospital ward. But is that us?

- What is it we actually experience? Can mind and consciousness operate and exist independently of the brain? Is it inside or outside the body? Is it inside the body or out there in space? Is it anywhere at all? Is the mind one and whole or is it made up of many parts? Where do we experience it? Where do we feel it? Is it everywhere or nowhere? Don’t answer with a concept or a theory-- just look! Is this mind you?

- What is this mind? Is it our thoughts and ideas? Is it our feelings and our emotions? Is it our sensations? Is this mind a thing or a substance? Or is it a process, a process with constantly changing contents like a stream of water? Is it cognition or a thought process? Or is it awareness? What is mind and what is consciousness? What is consciousness and what are the contents of consciousness? Just observe and find out for yourself! Mind is not a substance or a stuff; it is not a thing, an entity, or a mechanism--

It is a process. It is a stream of constantly changing events occurring in varying degrees of consciousness. At times this consciousness is bright and focused, at other times dull and diffused, at yet other times subliminal, almost unconscious. What we conventionally call “our mind” is this individual stream of consciousness. This is what the Buddha discovered sitting beneath the tree and meditating.

- When we look for the mind, what do we find? Where is it located? Thoughts fill our mind. Thoughts are events that arise in this stream of consciousness. But where are these thoughts located? Where do they come from? Where do they stay? Where do they go? Just look and observe. Is there one mind or many? What do we find? Do we find anything at all?

- Yet there is always consciousness and awareness present. Here there is a process in operation rather than an entity or a substance. The mind is insubstantial, but this does not mean that the mind does not exist. When we look inside of ourselves and just observe, we find that there is only a stream of consciousness (T. shes-rgyud, S. vijnana-santana). The Buddha introduced this term long before William James did some hundred years ago. When we say “my mind”, this refers not to a thing or a vestment. Yet this stream of consciousness has a continuity and an individuality. Our stream of consciousness is separate from those of other people. There are individual streams of consciousness and individual mental processes. We are not all One Mind. If we were, as soon as one of us realized something, all of us would simultaneously realize it.

- This stream of consciousness and its contents constitutes the Primary Level of our experience. Here we find our basic operating system, and it is both automatic and voluntarily. The other programs of perception, ego identification, and conceptualization all operate on top of this, on what we may call Levels 2, 3, and 4. The elementary events that occur in this stream of consciousness are called phenomena or dharmas. They are what we actually experience at the Base Level. But what we call reality is something constructed by complicated secondary and tertiary mental processes operating above the Base Level. Indeed, these very processes construct for us what we call “reality”, that is to say, our conventional common-sense everyday notions of what constitutes reality. But that is not what we actually experience. Our perceptions of reality are conceptual constructions.

Thus, we live in our conceptual constructions of reality and not in reality itself. Thoughts and conceptual constructions all take time to form, even if that time is only a fraction of a second. Therefore, when our conscious dwells in them, we are living in the past and not in the present in terms of what we actually experience here and now.

- OBSERVING THE MIND

- But how can we observe the mind? In the Buddhist tradition, there are methods provided for this. All what we know, we know through the mind. So, in order to discover ourselves we must begin with the mind and what we experience directly through the mind. Meditation is a key means for exploring the mind.

- The future Buddha, Prince Siddhartha, studied meditation under two different teachers. Practicing these methods he came to realize various altered states of consciousness, even cosmic consciousness or what is called mystical experience. Then he realized that these states did not represent liberation from Samsara. They were conditioned states of consciousness and therefore impermanent. He sought to discover a state beyond time and causality. He sat beneath the tree of knowledge, guarded by the serpent, and shortly before dawn he discovered this, the great secret. His eye of wisdom had penetrated into the nature of reality. But with the Buddha, the view of reality, spirituality, and human existence was radically different from the conventional views and from our common sense. Discerning the nature of reality, he spoke not of reality as substance, but as process. He spoke not of a thing or entity called “mind”, but of a stream of consciousness. And to speak about experience, he had to develop a process language.

Instead of speaking about a self as a substance (atman), he spoke of the five skandhas, or five interactive processes involved in every event in consciousness. Thus, we may speak here of processes and the mind-stream as against substances and entities. All we actually know is this stream of consciousness and its contents. The world that we perceive out there is a conceptual construction, not an immediate experience. The Buddha made this quite clear.

- Is this an objective material world we perceive outside of ourselves? Matter is an abstract concept, not experience. This fact has been rediscovered in contemporary physics. Where is this matter? It is a combination we make from the senses of sight and touch. With modern science, we can analyze material reality into molecules, these into atoms, these into subatomic particles, these into quarks, and these into superstrings. But superstrings have only one dimension; they are just vibrations in space. So, what is left of hard solid matter? What is there out there in the world? We find only empty space and incessant energy.

- Similarly, the Buddhist teachings speak of the insubstantiality of all phenomena (shunyata) and the illusionary nature of all phenomena (mayavada). But the illusion we naively call “the real world” is not something passive like mistaking a rope for a snake in the evening twilight. It is something energetic and dynamic. This energy manifests as processes. We can discover the mind as process through the practice of meditation. As we have said, usually our mental processes are occurring very rapidly, often in terms of mere fractions of a second. So, how can we discover what we actually experience? Not what we think we experience, which represents judgments and concepts, but what we actually experience at the Primary Level. We have to slow down the processes of the mind and then observe.

- There are two principal aspects to Buddhist meditation practice whereby we can do this. First, there is shamatha, the process of slowing down the mind and calming the mind by way of focusing attention on a single object of meditation. This process calms the mind so that it is no longer agitated and distracted by extraneous thoughts. Second, there is vipashyana, the process of higher insight where we observe the workings of the mind with clarity. But first we place the mind in a calm state before we can develop clarity in terms of introspection or looking within. Through this calm state, combined with higher insight, we can discover consciousness at the Base Level or Primary Level of immediate experience instead of being entangled in networks of thoughts and preconceptions.

- Level 1 is the primary level of immediate experience in the present moment and the stream of consciousness. This is the pure phenomena of consciousness before judgment and concept comes into play. This is the moment of pure awareness or primary cognition (jnana, ye-shes) before the mind (manas, yid) comes into operation with its judgments and concepts. In a sense, we could say that this pure awareness is beyond the mind, at least in the sense that it occurs before the various mental processes of the mind come into operation. Sensation occurs at this primary level.

- Level 2 is the secondary level at which the processes of perceiving, thinking, judging, and conceptualizing come into operation. Language and memory also come into operation here. Collectively these processes are known in Buddhist psychology as Samjna or functional perception. It is this meta-process that organizes sensation into a recognizable perception having an identity and a name. Collectively, the programs that accomplish this are known as Manas or the functional mind. In some ways this Manas may be compared to a computer with its basic operating system and word processing programs..

- Level 3 is the tertiary level at which occur ego identification and emotional reactions. Ahamkara or ego identification is the process where we identify ourselves with each sensation, thought, or emotion that arise in consciousness. This false identification is then compounded by Atmagaraha or grasping at this fictitious “I” which does not belong to immediate experience. As a result, certain impulses, thoughts, and emotions arise out of unconsciousness as reactions to the perceptions constructed at the secondary level. These are known as samskaras or unconscious impulses. These impulses include both thoughts and emotions; they basically represent energy emerging from the unconscious. Action may occur at this point impulsively or there may occur a further elaborations in terms of thoughts and emotions.

- Level 4 is the quaternary level at which the advanced programs are run, those relating to culture, social and personal interactions, as well as ethical considerations. Here commences the processes that elaborate thoughts, building the original perception into a concept and a thought construction. This is the meta-process of Vikalpa or discursive thought. It is on this plane that our consciousness usually dwells, the plane furthest removed from immediate experience in terms of time and space. When discursive thought is operating, the immediate experience is already long in the past. Therefore, our consciousness is living in the past, not in the present.

- Manas or the functional mind runs like a batch of computer programs operating above the basic operating system. Manas is our human bio-computer and it may run of times on automatic. But a mechanical computer lacks consciousness and although we human beings are made of flesh and blood, we are not machines, but are self-conscious and aware. We humans are much more than a computer. A computer is merely a sophisticated tool, a very useful one, but even a very young child can do many things the most advanced computer cannot.

The consciousness that operated in association with the perception process and the functional mind is known as Manovijnana or mental consciousness. It is this consciousness that is aware of thoughts and thought processes. In some ways Manas can function as a sense organ, being aware of mental events, but it also has the integrative function of organizing raw sense data into recognizable perceptions.

- We may ask, what lies below or beyond this Level 1? That is Level 0 or what is called in Buddhist terminology Shunyata. This term literally means “emptiness”. But this does not mean just nothingness or mere absence. Rather, it means the pure potentiality for all possible manifestations. This level may be compared to an empty mirror that has the capacity to reflect whatever is set before it. Whereas the other levels, primary and above, are referred to as mind (sems), this level is referred to as the Nature of Mind (sems-nyid). The distinction between mind and the Nature of Mind are like the reflections and the mirror. This Nature of Mind has the capacity to be aware of whatever may arise or manifest. This capacity is called Rigpa or intrinsic awareness. Whereas Sutra meditation and Abhidharma psychology is concerned with the phenomenology of consciousness (Levels 1-4), Level 0 is accessed directly through Dzogchen practice.

- BASIC MEDITATION PRACTICE

- The first thing we need to discover in meditation practice is something called mindfulness or mindful awareness. This is basic. Mindfulness is an awareness that is present together with our immediate experience, whether sensations, thoughts, or emotions. This awareness is not distracted or caught up in any secondary mental processes, but remains at the primary level of immediate experience.

- The first exercise is called “mindfulness on breathing”. First sit down comfortably, on a cushion on the floor or on a chair, but making sure that the back is straight. This harmonizes the flow of psychic energy in the body. We will be sitting still and unmoving for a time. This is the opposite of our usual everyday habit of running around and being distracted. Relax and do some deep breathing in order to release stress and tension. But here we have relaxation with alertness, which is the opposite of being sleepy, drowsy, and dull. We are alert and fully awake. But sitting calmly and quietly.

- We are not thinking about anything, but are open and globally aware. This is not absorption or trance or withdrawal of the senses. The senses are open and operating fully. This is what is meant by “clarity”. We ground and center ourselves just where we are in our immediate experience. Just be here now. This is like a tree, just being. It is nothing special. It is just sitting and being centered. It is not doing anything special. We are alert and aware without distractions. Distractions are what move us off center. They take us on a trip and we forget who and where we are. This just being present and aware is what is called mindfulness.

- The classical Buddhist exercise for mindfulness is fourfold: there is mindfulness on bodily sensations, mindfulness on feelings and emotions, mindfulness on thoughts, and mindfulness of subliminal processes. Mindfulness is just being present. It is self-remembering, a remembering to be aware, a coming back to center again and again. It is necessary first to develop this mindful presence so that we can engage in self-observation or introspection. We can be easily distracted; that is our habit and we continuously impose our conceptions on what we experience. So, it is necessary to have a focus for our awareness.

- In this case, we begin with the physical body and focus our attention and our full concentration on our breathing, just the sensations and sounds of our breathing. Breathing is part of our entire dimension of energy. Breathing links our body and our mind. It is a system that is both automatic and voluntary. In this case, we are just breathing normally with our eyes closed and sitting quietly. We simply focus on our breathing. If we become distracted or if thoughts arise, simply come back to focusing on our breathing. Just watch this breathing, be in this breathing. We are not thinking about our breathing or judging it. We just let it be without elaborations. This is known as Anuprana-smriti, practicing mindfulness again and again on our breathing. In this way, we can discover our awareness.

- [Note: This is a partial transcript from the workshop entitled “Self-Discovery through Buddhist Meditation”, presented by John Myrdhin Reynolds at Phoenix, Arizona, on October 20, 2001.]