Worldly Protector Deities in Tibet

The Tibetan plateau is often portrayed as a vast, sparsely populated land, but for Tibetans it is over- flowing with a surfeit of gods and spirits. Perhaps this is why the immense collection of Tibetan protector deities is often referred to as an “ocean” in the relevant literature (Khri byang 03, 199[?]; Klong rdol bla ma, 1973; Slelungrje drung, 1976;

Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, 1992). Protector deities (srung ma), often called Dharma protectors (chos skyong; Skt. dharmapāla) or “Oath-bound Ones” (dam can), have always played a significant role in the practice and propagation of Tibetan Buddhism.

Most Buddhist monasteries have a protector chapel with its own distinct pantheon of deities connected to the history of that institution and its sectarian affiliation.

These centers generally have extensive liturgical manuals (bskang gso), the performance of which are done throughout the ritual year to stimulate the continued protection of the monastery and local community by these deities. Most Tibetans likewise pray to protector deities at monasteries and before their home shrines for a myriad of reasons.

Laymen and laywomen beseech protectors often for more worldly concerns, such as fending off illness or death from a family, guarding crops and livestock from wild animals, or shielding the village from enemies and destructive weather. The activities of protectors are often divided into four categories (las bzhi): pacification (zhi), augmentation (rgyas), subjugation (dbang), and destruction (drag) (Cuevas, 2015, xxi–xxiv).

Much like tantric practitioners in their ritual ministrations, the deity will work through these four activities in the process of combatting negative forces, both seen and unseen. In this way, protector deities are active in all levels of Tibetan society, keeping back baneful influences and insuring auspicious connections or material support so that the Dharma and the community continue to flourish.

Protector deities themselves are drawn from a dizzying array of spirit types that are clan like in their categorization (Tucci, 1949, 711–730). Terms like Dharma protector or guardian deity are labels that can be applied to any kind of divinity that has been ritually, and often forcefully, subjugated by a tantric specialist.

The most popular narrative trope in this regard involves the famous 8th- century tantric master Padmasambhava, whose various hagiographies recount the numerous local gods he tamed as he traveled across India and Tibet (O rgyan gling pa, 1996; Douglas & Bays, 1978). Other Buddhist masters throughout Tibetan history have taken part in this process as well, such as Mi la ras pa (1052–1135; Quintman, 2010), Rwa lo tsa ba Rdo rje grags (1016–1128/1198; Cuevas, 2015), and Sog bzlog pa Blo gros rgyal mtshan (1552–1624; Gentry, 2017).

As for the types of spirits that become protector deities, they include a mix of Tibetanized Indian divinities, such as yakṣas (gnod sbyin), nāgas (klu), and rākṣasas (srin po), as well as strictly indigenous gods, such as rgyal po, btsan, and dmu (Spirits of the Soil, Land, and Locality in Tibet; Tucci, 1949, 717–725; Cornu, 1990, 226–229).

These examples do not fully capture the impressive amount of terminology used to define these supernatural beings, and English words such as “demon” and “spirit” only conflate or elide their diversity. Beyond these spirit types, there are also ontological categories that distinguish where these and other supernatural beings stand on the spectrum of enlightenment in Tibetan Buddhism.

There are generally four such categories:

(1) enlightened buddhas, bodhisattvas, and tantric tutelary deities,

(2) transcendent Dharma protectors who are emanations of enlightened beings, which are called “supramundane guardians” (’jig rten las ’das pa’i srung ma),

(3) worldly Dharma protectors, called “mundane guardians” (’jig rten pa’i srung ma), who were once local spirits that were subjugated and placed within the Buddhist pantheon presided over by tantric deities, and

(4) the horde of untamed indigenous spirits from which worldly protectors are drawn and who often make up members of their retinue (de Nebesky- Wojkowitz, 1956, 3–5, 23).

While the above categorization scheme appears orderly, the reality is far messier when we consider individual deities and their narratives. There is disagreement within and between different Tibetan Buddhist sects about the ontological nature of some in Tibet 1255 protector deities.

One group will state that a certain deity or group of deities are simply worldly spirits, prone to karmic accretion like all beings in saṃsāra, while another group will claim that the deities are ultimately an emanation of enlightened beings (de Nebesky-Wojkowitz, 1956, 177). Although the following narratives focus on worldly protector deities, a few of the divinities explored below exhibit this ambiguity.

Important Sources

Within the discipline of Tibetan Studies, research on protector deities is still comparatively nascent.

The foundational resource one must first refer to when exploring Tibetan gods and spirits remains de Nebesky-Wojkowitz Oracles and Demons of Tibet

(1956). Drawing on over 200 Tibetan texts, many of them rare, Nebesky-Wojkowitz catalogued the major supramundane and mundane Dharma protectors one encounters in Tibetan Buddhism, as well as the numerous kinds of local spirits.

The work is an encyclopedia of deity iconography, mythology, and ritual practices, and de Nebesky-Wojkowitz even notes alternative spellings and narratives for most of the deities he discusses.

The book itself has something of an infamous reputation within Tibetan exile communities today. Because the author died at the exceptionally young age of 36, some believe that the wrathful deities themselves struck him down prematurely due to his irreverent handling of their secrets (Bjerken, 2004, 38; Blofeld, 1970, 73).

An even older source that merits mentioning is the three-volume work Tibetan Painted Scrolls by the Italian scholar G. Tucci (1949). While concerned with Tibetan Buddhist history and iconography overall, this work provides a great deal of useful, if unsystematic, material on Indo-Tibetan myths tied to important Buddhist divinities and protector deities.

The first work to give explicit and sustained attention to a Tibetan deity cult, in terms of its historical and ritual development, is A. Heller’s dissertation (1992a). Heller focuses on the institutional and iconographic evolution of the protector deity Beg tse, a wrathful red deity with three eyes who brandishes a sword, bow, and arrow while bringing a heart to his mouth.

She specifically explores Beg tse’s liturgical development as he moved from his initial Sakya ritual context into the lineage of the Dalai Lamas. Much of Heller’s scholarship concerns Begtse and other Tibetan deities, especially through an art historical and philological lens (Heller, 1988, 1990, 1992a, 1994, 1996, 1997, 2001, 2003, 2006).

S. Karmay's work also often explores Tibetan protector deities, as well as local mountain deities.

Most of his work has been reprinted (1998; 2005; see also 1988). Finally, a thorough doctrinal examination of the mundane/supramundane ontological dichotomy can be found in Seyfort Ruegg (2008).

Beyond these contemporary examples and a handful of articles by other specialists, however, the bulk of research conducted specifically on protector dei- ties is still limited to unpublished master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, and conference papers.

In terms of Tibetan material on protector deities, countless texts touch on the subject and most Tibetan masters have composed rituals and hagiographies concerning divinities. These texts are either found in various collected works or in monastic ritual collections.

Nevertheless, it warrants mentioning a collection of deity hagiographies that represents one of the most significant attempts to collect and standardize the mythologies of Tibetan protector deities.

This important work was composed by Sle lung rje drung Bzhad pa’i rdo rje (1697– 1740) in 1734, and is titled the Dam can bstan srung rgya mtsho’i rnam par thar pa cha shas tsam brjod pa sngon med legs bshad (Unprecedented Elegant Explanation Briefly Expounding the Hagiographies and Iconographies of the Ocean of Oath-Bound Guardians of the Teachings).

While this text is written from a Dge lugs pa point of view, Sle lung was particularly thorough about citing his numerous references in his attempts to reconcile conflicting accounts, making it an indispensable resource (Bailey, 2017).

Regardless of the current state of the field, the available Tibetan sources and existing scholarship show that the mythic narratives of worldly protector deities in Tibetan Buddhism are rich and varied.

They possess elements of Indian mythography, tantric cosmology, and indigenous Tibetan geography and history. There are a number of shared themes across these narratives as well. For instance, the origins of a wrathful protector deity can usually be traced to their past lives. It is often the case that these beings were once devout religious practitioners before something disrupted their practice.

After being reborn as a fierce spirit, they needed to be subjugated, sometimes multiple times, before being ritually forced to protect the Dharma.

To illustrate these dominant structures and elements, what follows are the mythic narratives of six popular Tibetan Buddhist protector deities divided into three thematic categories.

The first category concerns the nature of Indo-Tibetan rebirth accounts for one of the forms of the goddess Dpal ldan lha mo, as well as for the god Pehar. The second category focuses on protector deities as wrathful revenants, using the gods Tsi’u dmar po and Rdo rje shugs ldan as exemplars. The final category will look at the ’Bri gung Bka’ brgyud protectress A phyi Chos kyi sgrol ma and the three Sakya Witches.

While many protector deities are quite ecumenical, existing in the ritual corpora of several traditions, these latter goddesses are vivid examples of specifically sectarian protectors.

Inevitably, the narrative samples below do not include the numerous variations that exist for each divinity’s mythos.

While the decision to elaborate on some elements and condense or excise others can act as a standardizing method, it is important to be aware that divergences exist and a shift in emphasis or difference in detail often falls along sectarian lines. There is still a lacuna in the relevant literature concerning these nuances.

Indo-Tibetan Rebirths

Dpal ldan lha mo, Queen of the Desire Realm

Dpal ldan lha mo, which simply means “Glorious Goddess,” is a broad label for a number of popular female protector deities. Due to Dge lugs influence over the last several centuries, Dpal ldan lha mo is most often an abbreviation of Dpal ldan lha mo Dmag zor rgyal mo, one of the two main protectors of the Dalai Lamas’ lineage – the other being Pehar, who will be discussed below.

Another Glorious Goddess is Dung skyong ma, the “Conch Shell Protectress,” also called ’Dod khams dbang phyug ma, the “Queen of the Desire Realm,” who is found in Rnying ma, Sa skya, Dge lugs, and ’Brug pa Bka’ brgyud pantheons.

She is of white complexion and brandishes a flaming crystal sword while holding a jewel-vomiting mongoose. The mythic origins of this divinity are clearly drawn from both the Purāṇic corpus and the Rāmāyaṇa epic of India (Dimmitt & van Buitenen, 1978, 299–303; Swami Venkatesananda, 1988).

While the summary below is drawn principally from Heller’s work, the story is originally found in a text entitled Mkha’ ’gro ma me lce ’bar ba’i rgyud (Tantra of Burning Flames), found in the Rnying ma’i rgyud ’bum (Cog ro Klu’i rgyal mtshan, 1973; Heller, 1997, 287–288; Tucci, 1949, 218–219).

Beginning in the legendary past, while the devas and asuras were waging a war against one another, the bodhisattva Vajrapāṇi created the goddess Pārvatī, called Umā, to act as Śiva’s partner. From their union, Umā gave birth to the god Mahākāla and the goddess Cāmuṇḍī. The latter decapitated one of the prominent asuras and came to be known (in Tibetan) as Dung skyong ma. Soon after, the gods raided the demon city of Laṅkā, which was ruled over by Rāvaṇa, the antagonist of the Rāmāyaṇa.

While Rāvaṇa survived the assault, he gave his sister in marriage to Śiva in order to pacify the divine incursion. From their union another goddess was born, Remati, who became Dung skyong ma’s maid-servant.

Through this connection, Rāvaṇa saw and fell in love with Dung skyong ma, pining after her obsessively. One day, when the gods went to Laṅkā en masse to watch the monkey brothers Sugrīva and Vālī fight, Rāvaṇa saw an opportunity and devised a plot to capture Dung skyong ma. By taking the form of a beautiful deer, and with Remati’s assistance, Rāvaṇa successfully lured away and seduced the goddess.

Her mother Umā was furious with this transgression and cursed both Dung skyong ma and Remati by transforming them into ugly and ferocious rākṣasas. From then on, they ate the flesh of corpses and dogs, and even gorged on their own bastard children. Unhappy with their lot, the two demon- esses fled Laṅkā, but not before stealing Rāvaṇa’s scorpion-handled sword and a mongoose-skin bag filled with jewels.

After roaming aimlessly for a time, Dung skyong ma and Remati found their way to the ocean shore.

For a week, they practiced the wind cakra of Yama, the Lord of Death, until a great black storm arose and surrounded them. Amid that tempest, Dung skyong ma recited a prayer of aspiration, saying, “may I immediately give up this life, obtain the Secret Mantra practice, and gaze upon the Buddha’s face! May I become the Queen of the Desire Realm!

May Remati, my black maid-servant, act as my disciple for all time!” Immediately after making this vow, a great cyclone whipped the two demonesses into the sea, drowning them (Cog ro Klu'i rgyal mtshan, 1973, 118). Dung skyong ma was accordingly reborn as ’Dod khams dbang phyug ma.

Remati was eventually reborn as Dung skyong ma’s servant.

The first half of this mythic narrative loosely but vividly illustrates popular Indic elements. The battle of the devas and asuras is Purāṇic, while Dung skyong ma’s role closely parallels that of Sītā and her capture by Rāvaṇa in the Rāmāyaṇa (Swami Venkatesananda, 1988, 154–161). The monkey brothers Sugrīva and Vālī are also mentioned, but in a context quite condensed and removed from their usual role in the epic.

While the epic of the Rāmāyaṇa has been known in Tibet (de Jong, 1972; Mkha’ ’bum, 2000), this is a particularly shallow iteration, since the protagonist Rāma is absent altogether.

More tantric and indigenous Tibetan elements filter in toward the end of the myth. The scorpion handled sword does not appear in Indian versions of the epic, since the pernicious and poisonous scorpion is a predominantly Tibetan symbol (Heller, 1997).

The Yama ritual is also distinctly tantric in nature

Beyond this, the tale evinces a brief but powerful rebirth and conversion account that reaches its crescendo with a prayer of aspiration; the women vow to be reborn as seekers of awakening in a classic expression of the Mahāyāna bodhisattva vow.

Pehar

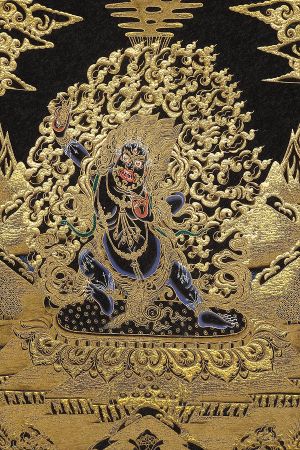

The Dharma protector Pehar is a wrathful protector deity, possessing three heads – black, white, and red – and six arms, each grasping a weapon. He is the chief of a group of five deities called the Five Sovereign Spirits (rgyal po sku lnga). While these divinities are generally considered worldly protector deities, they are occasionally referred to as supramundane protectors, especially at Gnas chung Monastery, their chief ritual and institutional center on the outskirts of Lhasa (Nair, 2004, 28–34).

The other deities that make up the Five Sovereign Spirits are believed to emanate from Pehar, and seldom appear in their own mythic accounts. By contrast, Pehar has a robust mythology that illustrates both classical Indian and indigenous Tibetan narrative tropes. The deity’s mythos can be divided into three major events: Pehar’s many lifetimes prior to Tibet, his arrival in Tibet, and his establishment at Gnas chung Monastery.

According to Sle lung, many eons ago in the land of the asuras, there was a devout king named Dharmajvāla. His closest friend was his minister Legs ldan nag po. Being quite religious, the two friends decided to become monks. Dharmajvāla took the ordination name Zla ’od gzhon nu, while Legs ldan nag po took the name Dun ting nag po.

However, while the king delighted in philosophy his minister delighted in meditation, causing them to drift apart. Later, Zla ’od gzhon nu saw the beautiful daughter of a brahmin and began an illicit affair with her. His old friend Dun ting nag po reproached him for this, which angered Zla ’od gzhon nu. From then on, and for several lifetimes, Zla ’od gzhon nu would transform into various animals to torment Dun ting nag po, only to be stymied by the bodhisattva Vajrapāṇi.

This negative activity ultimately caused Zla ’od gzhon nu to be reborn in hell, and to experience other unpleasant lives. Later, Zla ’od gzhon nu was born among wrathful spirits as a great white three-faced, six-armed man, while the monk Dun ting nag po became an arhat named Legs ldan nag po.

One day, when the awakened monk Legs ldan nag po was settled in the meditation of Hayagrīva, Zla ’od gzhon nu transformed into a great iron scorpion and bit Legs ldan nag po’s foot, but the arhat, emboldened by Vajrapāṇi and taking on the form of Hayagrīva, subjugated the fierce spirit.

In his next life, Zla ’od gzhon nu came to reside in the Bha ta hor region, near modern day Qinghai Lake. One day, when the great tantric master Padmasambhava was dwelling in a cave at Bha ta hor, Zla ’od gzhon nu transformed into a white lion to test the master.

Just as the lion was about to pounce on Padmasambhava, the exorcist took on the form of Hayagrīva and struck the beast with his staff. The spirit then transformed into a frightening black monk and threw a meteor down onto Padmasambhava’s head. Once again the master took on the form of Hayagrīva and seized the spirit. Zla ’od gzhon nu finally transformed into a young layman and bowed before the master, who subjugated him (Sle lung rje drung, 1976, 369:4–378:4).

Although Sle lung does not discuss Pehar’s arrival in Tibet, the Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682) does in his 1643 history of Tibet entitled, Gangs can yul gyi sa la spyod pa’i mtho ris kyi rgyal blon gtso bor brjod pa’i deb ther rdzogs ldan gzhon nu’i dga’ ston dpyid kyi rgyal mo’i glu dbyangs (Song of the Spring Queen that is a Celebration of the New Golden Age: A History that Expounds on the Main Heavenly Kings and Ministers that Ruled over the Land of Snows).

According to this source, in the 8th century, the Tibetan Dharma King Khri srong lde’u btsan invited the abbot Śāntarakṣita and Master Padmasambhava to establish Tibet’s first Buddhist monastery, called Bsam yas (Kapstein, 2006, 68–69). A guardian for Bsam yas’s treasury was needed, and eventually the current incarnation of Zla ’od gzhon nu, now named Pehar, was chosen to take this office.

As such, King Khri srong lde’u btsan’s son went with an army to Bha ta hor and brought Pehar back to Bsam yas (Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, 1993, 187:4–188:3).

Pehar’s eventual transfer to Gnas chung Monastery is elaborated upon in the biography of a ’Bras spungs Monastery abbot named Lcog pa Byang chub dpal ldan .

This text is attributed to Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho, the Fifth Dalai Lama’s final regent (Sørensen, Hazod & Tsering Gyalbo, 2007, 216–218), and states that Pehar left Bsam yas and came to reside at Yang dgon Monastery in Tshal, southeast of Lhasa.

Sometime in the late 15th to early 16th centuries, due to the past karma of the myriarch lord of Tshal, Don yod rdo rje (1462/1463–1512), Pehar took possession of an oracle and prophesied that he would abandon Don yod rdo rje’s lineage when he died and when Gung thang Monastery was destroyed by fire. In response to this prophecy, Don yod rdo rje became very angry and threw Pehar and his sacred possessions into the Skyid chu River (Sørensen, Hazod & Tsering Gyalbo 2007, 217).

At noon the next day, Pehar and his sacred items came to rest on the banks of the Skyid chu River below ’Bras spungs Monastery. The abbot of Bde yangs College at ’Bras spungs, Lcog pa Byang chub dpal ldan, instructed two attendants to retrieve the deity.

When Pehar came before Lcog pa Byang chub dpal ldan, the deity stressed that his sacred items lacked a home, so he offered to act as a guardian for the abbot and the monastery in exchange for a dwelling. In response, the abbot built a shrine to house Pehar’s possessions, calling it a small abode (gnas chung) for the Dharma protector (Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho, n.d., 10a.5–15a.2; Bell, 2013, 600–602).

Pehar’s pre-Tibet existence and iconography unequivocally reflect the primary plot structure and themes found in the Subjugation of Rudra, the foundational tale of demonic taming at the root of the 9th-century tantra, Dgongs pa ’dus pa’i mdo (Great Compendium of the Intentions of All the Buddhas Sūtra; Rdo rje thogs med, 1982, vol. XVI, 223–227).

In this subjugation myth, the title villain likewise starts out as a religiously devout student along with his servant, only to misunderstand his master’s teachings and corrupt his practice over time while his servant excels (Dalton, 2011, 159–206). This narrative kernel itself seems to parallel the tale of Indra and Vairocana found in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad (Olivelle, 1996, 171–175).

The two deities study under the same teacher, Prajāpati, but only Indra takes the time to fully understand his profound teachings, while Vairocana misapprehends their meaning. This provides an Upaniṣadic etiology for why Indra and the Vedic devas are superior to Vairocana and the demonic asuras.

Returning to the Compendium of Intentions, after countless horrible lifetimes, the corrupt student eventually became the ferocious three-headed, six-armed demon named Rudra, while his former servant became the enlightened tantric bodhisattva Vajrapāṇi. It is Vajrapāṇi, along with Hayagrīva, who ultimately subjugate Rudra, who in the end is given the initiation name Legs ldan nag po.

These names are all echoed in Pehar’s mythos, since it is Legs ldan nag po who is his former dharma brother, Vajrapāṇi who helps subjugate him, and Hayagrīva who is summoned through tantric ritual to aid the process. Moreover, the framing story of the Compendium of Intentions involves Vajrapāṇi relating the subjugation myth to Rāvaṇa, the demon king of Laṅkā and antagonist of the

Rāmāyaṇa, though in this tantric context he is a Buddhist devotee. Pehar’s origins can thus be traced to Vedic, Epic, and tantric Indian narrative contexts.

It is with Pehar’s arrival in Tibet that his mythology stands on more indigenous ground. Being subjugated by the 8th-century tantric exorcist Padmasambhava brings Pehar into the larger narrative tradition of the great master’s exploits, taming pernicious gods and spirits as he makes his way across the Land of Snows. The famous biography of Padmasambhava, the Padma bka’ thang

(Padma Chronicles), discovered by the treasure revealer O rgyan gling pa in the 14th century, even offers a more condensed but nonetheless vibrant account of Pehar’s subjugation (O rgyan gling pa, 1996, 648–661).

Pehar’s association with King Khri srong lde’u btsan and his son, as well as the founding of Bsam yas Monastery, further link the deity to Tibet’s legendary imperial past.

When Pehar makes his circuitous way from Bsam yas to Gnas chung, the protector deity not only has a more direct presence in comparatively recent Tibetan history, but also in sectarian and political affairs as well.

It seems likely that Pehar had close ties with the Tshal pa Bka’ brgyud lineage that eventually soured, as the tale of Don yod rdo rje above signifies – at least according to the predominantly Dge lugs narrative at Gnas chung.

This resulted in the deity’s rejection by the Tshal pa and acceptance by the Dge lugs at ’Bras spungs Monastery, paving the way for his inclusion in the burgeoning lineage

of the Dalai Lamas. The Dharma protector’s growing involvement in the ritual activity of the Second, Third, and, especially, Fifth Dalai Lama is indicative of this expanding prestige within Dge lugs circles.

This heightened importance culminates in the late 17th century when, under the auspices of the Fifth Dalai Lama, Pehar is made one of the two central protectors of the Dalai Lama lineage, alongside Dpal ldan lha mo Dmag zor rgyal mo.

Moreover, the Gnas chung Oracle, a monk who channels the spirit of Pehar and his emanations, has also been a constant source of clairvoyant guidance for the Dalai Lamas’ government since the 17th century.

Wrathful Revenants Tsi’u dmar po

The red Dharma protector Tsi’u dmar po is another popular ecumenical deity, found in all major sectarian traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. He has his origins in 16th-century Rnying ma treasure literature, but became absorbed into the Dge lugs pantheon by the

end of the 17th century. According to Sle lung, Tsi’u dmar po’s story begins in the legendary past, when the King of Khotan and his queen had a son named ’Phyor ba.

As an adult, ’Phyor ba became extremely religious and joined a monastery. His monastic name was Candrabhadra. He later went to dwell in the forest of a kingdom ruled by King Dharmaśrī. One day, while ’Phyor ba was in the forest, the daughter of the king was bathing in a nearby pool.

She was attacked by a poisonous snake and ’Phyor ba, seeing her distress, came and applied medicine to her wound. At that very moment two of the king’s ministers saw this and, misunderstanding it, reported back to the king. They told the king that a ruffian was

having sex with the princess, causing the king to become very angry. He summoned his servants and ordered them to find the monk and kill him.

Upon her return, the princess explained what actually happened and pleaded with her father, but no one would listen to her. Frustrated, she leapt off a cliff after uttering a regressive prayer (log smon) – a curse exclaiming that her next rebirth will be a wrathful and vindictive one rather than a compassionate and beneficent one.

’Phyor ba later learned of these events and fled the kingdom. Due to this traumatic affair, his thoughts became disturbed and he regressed in his practice. He went to Tibet, and in the domain of a king related to Dharmaśrī, he poisoned the men and raped the women. One day, the king sent forth his champion soldiers and they captured ’Phyor ba on a mountain path.

Pierced by many swords and on the verge of death, he exclaimed, “I will be reborn as a terrifying yakṣa that will destroy all beings!

I will come to kill the king and his ministers!” Due to his maliciousness and arrogance, ’Phyor ba was immediately reborn in a demonic land inside a red blood egg. When the egg burst open, the ferocious spirit Tsi’u dmar po was born.

Because of his great hatred, six other btsan spirits emanated from Tsi’u dmar po’s body. They arose from his head, bones, body heat, blood, pus, and garments of flesh, respectively. These seven deities, called the Seven Blazing Brothers (’bar ba spun bdun), slaughtered everyone around them, consumed the life energy of sentient beings, and brought ruin to the three realms.

The great bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara admonished these seven brothers for their severe misconduct, so that they promised to protect the Buddhist teachings thereafter.

Later in India, the great spiritual master Padmasambhava arrived at a charnel ground on the banks of a boiling lake of man eating demons. At midnight, he heard seven wolves with blood-clotted hair cry out, so the master manifested the form of Hayagrīva. The wolves retreated to their masters, the seven brothers, and the latter prostrated themselves before Padmasambhava.

The spiritual master asked them who they were and the leader of the horsemen replied, “I am Tsi’u dmar po, lord of the yakṣa. Previously, Hayagrīva conferred empowerments on my team and from then on we promised to guard the Buddhist teachings.” Padmasambhava then asked about Tsi’u dmar po’s residence, parent- age, and life essence. Tsi’u dmar po replied, “my abode is this very charnel ground of India.

In Tsang, it is called the split cavern. My father is Legs pa, lord of the dmu. My mother is the yakṣa Gdong dmar ma. The essence of my life energy is a tantra recited by glorious Hayagrīva.” Then the great spiritual mas- ter bestowed empowerments on Tsi’u dmar po and

gave him a secret name. Later, when Padmasambhava arrived in Tibet, he was welcomed by Tsi’u dmar po and his team of riders (Sle lung rje drung, 1976, 458–470).

There is some complexity in the conversion portion of this narrative. The root tantra explains that Tsi’u dmar po and his team of horsemen were subdued and converted by Avalokiteśvara, yet its

accompanying ritual scripture and Sle lung’s text state that the seven horsemen were initially subdued by Hayagrīva. Since Hayagrīva is generally considered a wrathful emanation of Avalokiteśvara, the subtle difference seems to be a matter of narrative preference. Regardless, after an encounter with Padmasambhava, the horsemen’s vows to protect the Buddhist teachings were renewed.

This need to repeat a deity’s subjugation is a common trope in Dharma protector narratives and is reflected in most of their liturgical manuals, where the divini- ties must be reminded of their vow to protect the teachings of the Buddha before being entreated to perform a requested action Rdo rje shugs ldan

A more recent historical example of the wrathful revenant is the controversial protector deity Rdo rje shugs ldan. This divinity continues to be the focus of an intra sectarian fissure in the Dge lugs school of Tibetan Buddhism today (Repo, 2015; Dreyfus, 1998).

In fact, it is likely that the conflict is a late 20th- century development, since the deity appears in Sakya and Bka’ brgyud ritual texts prior to the 20th century.

In his chapter on Rdo rje shugs ldan, de Nebesky-Wojkowitz (1956, 134–144) likewise makes no note of a disagreement. As it stands today, the divide primarily centers on the deity’s ontological status. Proponents of his worship consider Shugs ldan to be either an enlightened emanation of the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī or a buddha in his own right.

Opponents, who make up most Tibetan Buddhists and include the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, claim that Shugs ldan is a pernicious spirit that promotes heterodox practices and threatens Tibetan unity (Tenpai Gyaltsan Dhongthog, 2000).

For all the controversy that surrounds [[Rdo rje shugs ldan], he is a comparatively “new” protector deity, since his story begins with a 17th-century monk named Grags pa rgyal mtshan (1619–1656).

As with all protector deity narratives, there are conflicting details, but most accounts claim that Grags pa rgyal mtshan and the Fifth Dalai Lama were rivals. Grags pa rgyal mtshan himself was one of the children considered to be the reincarnation of the Fourth Dalai Lama before the child who would become the Fifth was ultimately chosen.

Instead, Grags pa rgyal mtshan was determined to be in the incarnation line of the great Dge lugs hierarch and 15th abbot of Dga’ ldan Monastery, Paṇ chen Bsod nams grags pa (1478–1554).

Having gone through the monastic curriculum as peers and rivals, [[Grags pa rgyal mtshan’s] intelligence and popularity began to challenge that of the Great Fifth’s. The strained relationship reached its conclusion when Grags pa rgyal mtshan died under mysterious circumstances. In his autobiography, the Fifth Dalai Lama states simply that the monk died of a sudden illness (Karmay, 2014, 364–365).

However, later popular accounts state that Grags pa rgyal mtshan was found with a Tibetan ceremonial scarf stuffed down his throat, either through suicide or murder – the latter supposedly committed by a henchman of the Dalai Lama’s minister (Dreyfus, 1998; McCune, 2007).

A detailed account of the aftermath of Grags pa rgyal mtshan’s death can be found in the 20th-century work, [[Dge ldan bstan pa bsrung ba’i lha mchog sprul pa’i chos rgyal chen po rdo rje shugs ldan rtsal gyi gsang gsum rmad du byung ba’i rtogs pa brjod pa’i gtam du bya ba dam can rgya mtsho dgyes

pa’i rol mo]] (Music that Delights the Ocean of Oath- Bound Ones: A Discourse on the Biography of the Wonderful Three Secrets of Mighty Rdo rje Shugs ldan, the Emanated Great Dharma King, Supreme Deity who Protects the Dge lugs Teachings), composed by the third Khri byang, Blo bzang ye shes bstan ’dzin rgya mtsho (1901–1981), one of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s tutors.

According to this text, after Grags pa rgyal mtshan died, strange events started to occur, presumably caused by his vindictive ghost. The monk’s cremated relics were placed in a silver stūpa in his old residence at ’Bras spungs Monastery, but shortly thereafter visitors complained that they heard voices, knocking sounds, and other disturbances in the building.

To remedy this, the Dalai Lama’s minister placed Grags pa rgyal mtshan’s relics in a box and threw it into the Skyid chu River, where it floated down to an area called Dol in Lho kha. This had no effect, however.

The Fifth Dalai Lama had baneful visions, such as a black monkey with orange eyes following or riding a colleague. Other high officials and members of his cabinet had portentous dreams.

There would be slapping sounds against walls, plates of food would mysteriously overturn, prayer diagrams became ineffective, and ghostly voices would harass people.

There was an epidemic that caused the deaths of several monks. The Potala Palace, the Dalai Lama’s winter home, was itself shaken by an earthquake.

Grags pa rgyal mtshan’s former residence at ’Bras spungs Monastery even had to be destroyed in an effort to quell the malicious spirit. The Fifth Dalai Lama also built a protector house in Dol, but none

Worldly Protector Deities in Tibet 1261 of these efforts stemmed the tide of supernatural occurrences.

Finally, a destructive ritual was conducted by high Rnying ma lamas in an attempt to destroy Grags pa rgyal mtshan’s ghost. That rite also failed; the fire sacrifice was weak and a member of the ghost’s retinue supernaturally shook the Potala Palace with his spear to distract the Fifth Dalai Lama during his ritual ministrations.

Other distractions occurred in the course of the tantric specialists’ services. Even when one master tried to draw Grags pa rgyal mtshan into a ladle to then pour him into the ritual fire, he would not drop into it. The inauspicious circumstances continued. Monks suffered strokes and died, laypeople saw monks walking about with donkey heads, people were being possessed, and doctors were misdiagnosing illnesses.

Some accounts state simply that the Fifth Dalai Lama and his government finally made peace with Grags pa rgyal mtshan’s fierce spirit and requested that he act as a Dharma protector for the Dge lugs sect. Other accounts state that the spirit left Lhasa of his own

accord and attempted to act as a protector of Bkra shis lhun po Monastery in Gtsang, since it had been the home of his former teacher Paṇ chen Blo bzang chos kyi rgyal mtshan (1570–1662).

However, the spirit was barred from entering the premises by the protector deity Vaiśravaṇa and his retinue, so he traveled further west to Sakya Monastery and became a protector there, since that was the home of one of his previous incarnations, Sakya Paṇḍita (1182–1251). Later the spirit was given the Dharma protector name of Rdo rje shugs ldan, possibly by the Gnas chung Oracle himself (Khri byang 03, 199[?], 101.5–116.5).

In the case of both Tsi’u dmar po and Rdo rje shugs ldan, a devout monk was wrongfully murdered. Because of this misdeed, the monk became enraged and was reborn as a wrathful ghost that wrought havoc before finally being tamed, often after great effort. Another wrongfully murdered monk is the originator of one of the Sakya Witches discussed below.

Family and Sectarian Guardians A phyi Chos kyi sgrol ma

The specific protector deity of the ’Bri gung Bka’ brgyud sect is the Dharma protectress A phyi Chos kyi sgrol ma – not to be confused with the first Rdo rje phag mo incarnation of Bsam sdings Monastery, Chos kyi sgron ma (1434–1467/1468).

A phyi Chos kyi sgrol ma was the maternal great-grandmother of the tradition’s founder, ’Jig rten gsum mgon (1143–1217). Like Pehar, there is also some ambiguity about the ontological status of this deity. Although she is portrayed as a worldly Dharma protector, she is also considered a manifestation of the enlightened tantric deity Vajrayoginī.

Muldowney (2011) translated an abridged 20th- century hagiography of Chos kyi sgrol ma. This popular account states that the Wisdom Ḍākiṇī Vajrayoginī decided to be reborn in Central Tibet, specifically in an area called Gzho stod in the ’Bri gung Valley, within the

fortunate and prestigious Sna nam clan. She was born as the daughter of the Rnying ma yogin Sna nam pa Jo bo pal and his wife ’Bri za dar ’dzoms sometime in the early 11th century.

The two had initially wanted a son, so they went to the Svayambhū Stūpa outside Kathmandu, Nepal, to pray for one. The couple had auspicious dreams while in Nepal, and after nine months of good omens ’Bri za dar ’dzoms gave birth to a daughter.

She was born with a third eye and immediately spoke, claiming that her renown would permeate the world. Her parents were frightened by these signs, however, so they threw her into a nearby body of water. When she miraculously surfaced, they realized that she was special and took her home, although her father continued to wish that he had a son rather than a daughter.

The daughter was named Chos kyi sgrol ma, “Savioress of the Dharma,” because even at a young age she made a vow to dedicate her life to the Buddha’s teachings. She even taught her neighbors and friends as a toddler, much to their surprise. By the age of five, Chos kyi sgrol ma received Vajrayoginī teachings and spoke cryptically about meeting someone in Khams, in Eastern Tibet.

After a few years, Chos kyi sgrol ma’s father died of smallpox. When she was 18 years old, her mother died as well and she renounced her parent’s wealth as a result. She stayed with her uncle thereafter, but now that she was of age her marriage was on everyone’s mind. When a merchant traveling east came to town, Chos kyi sgrol ma left her home with him and his band, determined to reach Khams.

Once in Khams, Chos kyi sgrol ma met a Rnying ma master named Skyu ra Tshul khrims rgya mtsho.

Neither of them wanted the trappings of worldly Protector Deities in Tibet living, especially a conventional marriage, so they were pleased with each other and with focusing their energies on teaching the Dharma. Nevertheless, the nearby families and

neighbors panicked about the need for a proper marriage feast. In response, Chos kyi sgrol ma miraculously produced a tantric feast, and food and drink rained down on the wedding guests.

Shortly thereafter, Chos kyi sgrol ma gave birth to four virtuous sons. As her sons grew, Chos kyi sgrol ma developed magical powers and practiced her abilities in charnel grounds.

When they were older, she initiated her sons in the Vajrayoginī practice and continued to perform miraculous acts, such as binding pernicious spirits under oath. Numerous sacred sites in the area bear her mark to this day. Having composed her own sādhana practices, she promised to protect those who would continue to perform them after her death.

Chos kyi sgrol ma was over 70 years old when she passed away. One of her sons, Dpe ka dbang rgyal, likewise had four sons, and one of their sons was ’Jig rten gsum mgon, the founder of ’Bri gung mthil Monastery (Muldowney, 2011, 18–30).

Iconographically, Chos kyi sgrol ma is usually represented with three eyes and a semi-wrathful expression. She rides a blue horse while holding a double sided drum and a skull cup. She shares a number of attributes with the tantric deity Vajrayoginī (Muldowney, 2011, 49–52).

It is argued that A phyi Chos kyi sgrol ma’s hagiography is structured in such a way as to mimic that of the traditional 12-stage scheme of the Buddha Śākyamuni’s life story.

This scheme includes elements such as a celestial preexistence, an auspicious human birth, a renunciation of home and communal expectations, a series of miraculous activities, and an equally miraculous death and ascension to a blissful realm.

Nonetheless, there are notable divergences, such as Chos kyi sgrol ma having no ties to institutional Buddhist centers and using her children as a primary means for propagating the Dharma. It is also the death of Chos kyi sgrol ma’s parents that helps catalyze her decision to travel to Khams (Muldowney, 2011, 63–70).

Bailey (2016b) likewise sees the 12 stages of the Buddha’s life reflected and inverted in the fundamental subjugation of Rudra, discussed above as a major influence on Pehar’s mythology. In both instances, there is a tension between the nature and qualities of an enlightened being and that of an unenlightened worldly deity.

The Sakya Witches

To this day people fear and respect a trio of protector goddesses found at Sakya Monastery, known as the Sakya Witches (sa skya ’bag mo). While ’bag mo is here glossed as “witches,” it is much more ambiguous, referring to “living demonic women” or “wicked women.”

The myths surrounding these deities vary in detail and in thematic content, but in either case they speak to a specifically Sakya oriented ritual cosmos, institutional history, and regional protection.

According to Conrad (2012, 6–21, rendering Padma dbang ’dus, 1995), the “witches” are named Mus mo srid skyid, Nam mkha’ sgrol ma, and Shangs mo Rdo rje bu khrid.

The head of this team is technically Mus mo srid skyid, who is considered an emanation of Gurmgon’s consort – Gur mgon being the form of Mahākāla most revered by the Sakya tradition. Possibly due to her transcendent origins, Mus mo srid skyid does not have as rich a mythology as the other witches, who are recognized solely as worldly deities.

The second witch, Nam mkha’ sgrol ma, has her beginnings in the early 16th century, although she does not become a protector deity until a century later. According to tradition, there was a Sakya master named Kun dga’ rin chen who, during his youth, trained under his famous uncle, the head of the Sakya School, Sa lo chen po ’Jam dbyangs kun dga’ bsod nams (1485–1533).

When he became an adult, Kun dga’ rin chen went to reside at Sakya Monastery in hopes of shoring up and expanding the Buddhist teachings.

However, before he could get started, the minister of Lhasa and his army forcefully occupied the [[[Sakya]]]] lands and closed the monastery. Since his uncle, the Sakya Throne holder, had passed away by this point, Kun dga’ rin chen fled the region. He went off to the fringes of the Sakya territory in order to practice and study on his own.

One day, Kun dga’ rin chen’s uncle miraculously appeared in the sky before him and entreated him to remain strong and resolute in his goals. Kun dga’ rin chen returned to Sakya Monastery with his hopes revived, although he still feared for his life.

This fear was not unwarranted. Shortly after his return, one of Kun dga’ rin chen’s teachers, an old monk named Rab ’byams pa Bsod nams ’od zer, was captured by the Lhasa minister and his forces.

They tied him to a pillar and shot arrows at him until he died. Because of the disharmony his conduct inspired in the region, the minister was sent off to another place and control of Sakya was returned to its lineage holders.

It is said that when Rab ’byams pa Bsod nams ’od zer was on the brink of death, he stated with great intention, “as I pass from this lifetime, may I be born as the ruler (dbang ba) of one third of the world.”

However, because his mind was clouded with anger, he inadvertently said, “as I pass from this lifetime, may I be born as the devourer (za mkhan) of one third of the world” (Conrad, 2012, 74). Because of this regressive prayer, he was reborn in Khams as a living demoness or witch (’dre mo) named Nam mkha’ sgrol ma who immediately began harassing people and destroying property.

Generations later, in the early 17th century, Kun dga’ rin chen’s grandson, Sgra chen Mthu stobs dbang phyug (b. 1592) went to Khams to subdue Nam mkha’ sgrol ma. He was unable to tame this powerful demoness, so he took her as a sexual consort instead.

When she died, he skinned and tanned her flesh, and used it to make a lifelike mask. He infused the mask with her consciousness and imbedded a vajra at its forehead.

Once completed, Sgra chen Mthu stobs dbang phyug reminded the trapped spirit of Kun dga’ rin chen’s original vow to advance the Dharma, as well as Nam mkha’ sgrol ma’s original regressive prayer, and he commanded her to protect the Sakya teachings and lineages.

The mask was later placed in the Sakya Monastery protector chapel and this witch was placed in Gurmgon’s retinue. From that time onward the mask has been used every year during an annual ceremony, where it is worn in religious dances, resulting in miraculous visions and omens.

Oral tradition states that Nam mkha’ sgrol ma will appear as a beautiful young woman to help monks, nuns, and members of the local Sakya community. How- ever, she will appear as a screaming, blazing demoness to those who would harm Sakya villages and monasteries.

The third witch, Shangs mo Rdo rje bu khrid, has a simpler, more generic myth associated with her origins.

An unnamed Sakya throne holder summoned this witch from a region in Shangs, north- east of Sakya, and bound her to an oath to protect the Buddhist teaching.

She continued to serve the successive hierarchs of Skya thereafter. Nevertheless, there are a number of stories about her activities as a capricious protectress, one who needs to be constantly reminded of her vow.

As a protector deity, Rdo rje bu khrid also removes obstacles and helps those who go astray. In this latter capacity, the witch is said to appear in the form of a young local girl who guides people on their way and then vanishes when her services are no longer needed.

If enemies or thieves try to harm a Sakyapa, wherever they are, she will appear in a horrible form and kill them. She also has a mask that possesses magical properties (Conrad, 2012, 6–20).

In the case of these goddesses, both A phyi Chos kyi sgrol ma and the Three Sakya Witches were once family or local deities who came to be associated with specific schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

They can now be found represented iconographically and liturgically at the numerous institutional centers that promote these sects across the Tibetan cultural sphere.

Concluding Remarks

The above accounts are only a sampling of the narratives one encounters in the dense mythologies of Tibetan Buddhist protector deities. Nonetheless, most of them exhibit overarching themes and tropes. In many of these narratives, the protagonist is murdered and as a result professes a regressive prayer, which acts as an inversion of the bodhisattva vow.

Rather than praying to become a bodhisattva on the path to awakening, these figures promise instead to become terrifying and demonic spirits who vindictively hope to terrorize those who wronged them in a future life; they inevitably bring carnage to the world at large.

It requires the interference of powerful tantric buddhas, and the masters who embody them, before the fierce energies of these deities can be quelled and channeled into more constructive endeavors.

Some of these divinities can trace their origins back to Buddhist versions of Indian epics and mythic compilations. Others are explicitly Tibetan, either in geographic origin, indigenous symbolism, or sectarian affiliation; many even have Bon counterparts and influences (Bellezza, 2005; Gibson, 1991).

Most often one finds permutations of both cultural influences, which speaks to the South Asian origins of Buddhism and its assimilation into Tibetan culture. Although there are peaceful protector deities known for their pacifying activities, wrathful deities like those discussed above appear to be far more prevalent.

The worship of these ferocious divinities is in many instances legitimized by claims to their ultimately enlightened nature, such as in the case of A phyi Chos kyi sgrol ma and Pehar.

However, there is limited consensus on this, and in the case of Rdo rje shugs ldan it can even result in controversial disagreement and violence. Regardless, worldly protector deities permeate the Tibetan Buddhist imaginaire. Their myth can be found canonized in liturgical manuals and iconographies, represented in monastic murals, paintings, and statues, and preserved in oral accounts promulgated by Tibetans across the generations.

Bailey, C., 2017. “A Feast for Scholars: The Life and Works of Sle lung Bzhad pa’i rdo rje,” diss., University of Oxford.

Bailey, C., 2016a. “A Tibetan Protector Deity Theogony: An Eighteenth Century ‘Explicit’ Buddhist Pantheon and Some of its Political Aspects,” RET 37, 13–28.

Bailey, C., 2016b. “The Twelve Acts of Rudra: Buddha’s Mythic Inversion,” paper presented at the American Academy of Religion Annual Meeting, San Antonio.

Bailey, C., 2012. “The Raven and the Serpent: ‘The Great All-Pervading Rāhula’ and Dǽmonic Buddhism in In- dia and Tibet,” diss., Florida State University.

Bell, C., 2013. “Nechung: The Ritual History and Institu- tionalization of a Tibetan Buddhist Protector Deity,” diss., University of Virginia.

Bell, C., 2006. “Tsiu Marpo: The Career of a Tibetan Pro- tector Deity,” thesis, Florida State University.

Bellezza, J.V., 2005. Spirit-Mediums, Sacred Mountains and Related Bon Textual Traditions in Upper Tibet: Calling

Down the Gods, Leiden, Brill.

Beyer, S., 1973. The Cult of Tara: Magic and Ritual in Tibet,

Berkeley, University of California Press.

Bjerken, Z., 2004. “Exorcising the Illusion of Bon ‘Sha- mans’: A Critical Genealogy of Shamanism in Tibetan Religions,” RET 6, 4–59.

Blofeld, J., 1970. The Tantric Mysticism of Tibet: A Practical

Guide, Repr. 1982. Boulder: Prajñā Press.

Cog ro Klu’i rgyal mtshan, trans. (8th cent.), 1973. Mkha’ ’gro ma me lce ’bar ba’i rgyud, in: Rnying ma rgyud ’bum,

vol. XXXIII, Thimphu: Dingo Khyentse Rimpoche, 102– 193; BDRC: W21518.

Conrad, S.M., 2012. “Oral Accounts of the Sa skya ’bag mo, Past and Present Voices of the Terrifying Witches of Sa skya,” thesis, Indiana University.

Cornu, P., 1990. L’astrologie Tibétaine, Millau: Les Djinns.

Cuevas, B.J., 2015. The All-Pervading Melodious Drumbeat: The Life of Ra Lotsawa, New York: Penguin.

Dalton, J., 2011 The Taming of the Demons: Violence and Liberation in Tibetan Buddhism, New Haven: Yale Uni-

versity Press.

Dimmitt, C., & J.A.B. van Buitenen, trans., 1978. Classical

Hindu Mythology: A Reader in the Sanskrit Purāṇas,

Philadelphia, Temple University Press.

Douglas, K., & G. Bays, trans, 1978. The Life and Libera- tion of Padmasambhava, 2 vols., Berkeley: Dharma Publishing.

Dreyfus, G., 1998. “The Shuk-den Affair: History and Na- ture of a Quarrel,” JIABS 21/2, 227–270.

Gibson, T.A., 1991. “From btsanpo to btsan: The Demoni- zation of the Tibetan Sacral Kingship,” diss., Indiana University.

Gentry, J.D., 2017. Power Objects in Tibetan Buddhism: The Life, Writings, and Legacy of Sokdokpa Lodrö Gyeltsen,

Leiden: Brill.

Heller, A., 2006. “Armor and Weapons in the Iconogra- phy of Tibetan Buddhist Deities,” in: D.J. LaRocca, ed.,

Warriors of the Himalayas: Rediscovering the Arms

and Armor of Tibet, New Haven: Yale University Press, 34–41.

Heller, A., 2003. “The Great Protector Deities of the Dalai Lamas,” in: F. Pommaret, ed., Lhasa in the Seventeenth

Century: The Capital of the Dalai Lamas, Leiden: Brill,

81–98.

Heller, A., 2001. “On the Development of the Iconogra- phy of Acala and Vighnāntaka in Tibet,” in: R. Lin- rothe & H.H. Sørensen, eds., Embodying Wisdom: Art,

Text and Interpretation in the History of Esoteric Bud-

dhism, Copenhagen: Seminar for Buddhist Studies, 209–228.

Heller, A., 1997. “Notes on the Symbol of the Scorpion in Tibet,” in: S. Karmay & P. Sagant, eds., Les Habitants du

Toit du Monde, Études Recueillies en Hommage à Alex-

ander W. Macdonald, Nanterre: Société d’éthnologie, 283–297.

Heller, A., 1996. “Mongolian Mountain Deities and Local Gods: Examples of Rituals for their Worship in Tibetan Language,” in: A.-M. Blondeau & E. Steinkellner, eds.,

Reflections of the Mountain: Essays on the History and Social Meaning of the Mountain Cult in Tibet and the Hi-

malaya, Vienna: Verlag de Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaft, 133–140.

Heller, A., 1994. “Early Ninth Century Images of Vairocha- na from Eastern Tibet,” Orientations 25/6, 74–79.

Heller, A., 1992a “Etude sur le développement de l’iconographie et du culte de Beg-tse, divinité protec- trice tibétaine,” diss., EPHE.

Heller, A., 1992b “Historic and Iconographic Aspects of the Protective Deities Srung-ma dmar-nag,” in: S. Ihara &

Z. Yamaguchi, eds., Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 5th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Narita 1989, vol. II, Narita: Monograph series of Naritasan Institute for Buddhist Studies, Naritasan- Bukkyō-Kenkyūsho, 479–492.

Heller, A., 1990. “Remarques Préliminaires sur les Di- vinités Protectrices Srung-ma dmar-nag du Potala,” in:

For use by the Author only | © 2019 Koninklijke Brill NV

Worldly Protector Deities in Tibet 1265

F. Meyer, ed., Tibet: Civilisation et Société, Paris: Éditions de la Fondation Singer-Polignac, 19–27.

Heller, A., 1988. “Early Textual Sources for the Cult of Beg-ce,” in: H. Uebach & J.L. Panglung, eds., Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 4th Seminar of the Interna- tional Association for Tibetan Studies. Schloss Hohen-

kammer – Munich 1985, Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 185–195. de Jong, J.W., 1972. “An Old Tibetan Version of the Ramāyāṇa,” TP 58/1, 190–202.

Kapstein, M., 2006. The Tibetans, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Karmay, S., 2014. The Illusive Play: The Autobiography of

the Fifth Dalai Lama, Chicago: Serindia Publications.

Karmay, S., 2005 The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals and Beliefs in Tibet, vol. II., Kath-

mandu: Vajra Publications.

Karmay, S., 1998. The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals and Beliefs in Tibet, Kathmandu:

Vajra Publications.

Karmay, S., 1988. Secret Visions of the Fifth Dalai Lama: The Gold Manuscript in the Fournier Collection, London:

Serindia Publications.

Khri byang 03 Blo bzang ye shes bstan ’dzin rgya m tsho

(1901–1981), 199[?]. Dge ldan bstan pa bsrung ba’i lha mchog sprul pa’i chos rgyal chen po rdo rje shugs ldan rtsal gyi gsang gsum rmad du byung ba’i rtogs pa brjod pa’i gtam du bya ba dam can rgya mtsho dgyes pa’i rol mo, in: Yongs rdzogs bstan pa’i mnga’ bdag 7 skyabs rje yongs ’dzin khri byang rdo rje ’chang

chen po’i gsung ’bum, vol. V, n.p., 5–159; BDRC: W14592.

Klong rdol bla ma Ngag dbang blo bzang (1719-1794). 1973.

Bstan srung dam can rgya mtsho’i ming gi grangs, in: The Collected Works of Longdol Lama, Parts 1, 2. Lokesh Chandra, ed. Śata-Piṭaka Series: Indo-Asian Literatures, vol. C. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture, 1254–1284; BDRC: W30182.

McCune, L., 2007. “Tales of Intrigue from Tibet’s Holy City: The Historical Underpinnings of a Modern Bud- dhist Crisis,” thesis, Florida State University.

Mkha’ ’bum, 2000. Rā ma ṇa’i rtogs brjod chos dbang grags

pa’i dgongs rgyan, Lanzhou, Kan su’u mi rigs dpe skrun khang; BDRC: W21878.

Muldowney, K., 2011. “Outward Beauty, Hidden Wrath: An Exploration of the Drikung Kagyü Dharma Protectress Achi Chökyi Drölma,” thesis, Florida State University.

Nair, U., 2010. “When the Sun’s Rays are as Shadows: The Nechung Rituals and the Politics of Spectacle in Tibet- an Exile,” diss., University of Chicago.

Nair, U., 2004. “The Sociological Inflection of Ontology: A Study of the Multiple Ontological Statuses of a Ti- betan Buddhist Protective Deity,” thesis, University of Chicago. de Nebesky-Wojkowitz, R., 1956. Oracles and Demons of Ti-

bet: The Cult and Iconography of the Tibetan Protective Deities, Repr. 1998. New Delhi: Book Faith India.

Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho (1617–1682), 1993. Gangs

can yul gyi sa la spyod pa’i mtho ris kyi rgyal blon gtso bor brjod pa’i deb ther rdzogs ldan gzhon nu’i dga’ ston dpyid kyi rgyal mo’i glu dbyangs, in: Thams cad mkhyen pa rgyal ba lnga pa chen po ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho’i gsung ’bum: The Collected Works (gsung ’bum) of Vth Dalai Lama Ngag-dbang-blo-bzang-rgya-mtsho, vol.

XIX, Gangtok: Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology, 3–228; BDRC: W294.

Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho (1617–1682), 1992. Thogs med drag rtsal nus stobs ldan pa’i dam can chos srung rgya mtsho’i mngon rtogs mchod ’bul bskang bshags bstod tshogs sogs ’phrin las rnam bzhi’i lhun grub, in: Thams cad mkhyen pa rgyal ba lnga pa chen po ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho’i gsung ’bum: The Collected Works (gsung ’bum) of Vth Dalai Lama Ngag-dbang-blo-

bzang-rgya-mtsho, vol. XI, Gangtok: Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology, 129–591; BDRC: W294.

Olivelle, P., trans., 1996. Upaniṣads, Oxford: Oxford Uni- versity Press.

O rgyan gling, pa (1323–1360), 1996. Padma bka’ thang, Chengdu:Si khron mi rigs dpe skrun khang; BDRC: W17320.

Padma dbang ’dus, 1995. “Sa skya’i ’bag mo zhes pa byung tshul lo rgyus ngag rgyun du chags pa ’ga’ zhig,” G.yum

tsho: Bod kyi bud med rig pa’i dus deb 3/3, Dharamsala:

A myes rma chen bod kyi rig gzhung zhib ’jug khang, 46–55.

Quintman, A., trans., 2010. The Life of Milarepa, New York: Penguin.

Rdo rje thogs med, ed., 1982. Mtshams brag Edition of the Rnying ma'i rgyud 'bum, 46 vols, , Thimphu Bhutan: Na- tional Library, Royal Government of Bhutan.

Repo, J., 2015. “Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo: His Col- lected Works and the Guru-Deity-Protector Triad,” RET 33, 5–72.

Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho, Sde srid (1653–1705), n.d. Lcog pa

byang chub dpal ldan pa’i rnam thar rags bsdus chos skyong chen po’i ’byung khungs dang bcas pa, Lhasa.

Seyfort Ruegg, D., 2008. The Symbiosis of Buddhism with Brahmanism/Hinduism in South Asia and of Buddhism with “Local Cults” in Tibet and the Himalayan Region,

Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Sle lung rje drung Bzhad pa’i rdo rje (1697–1740), 1976.

Dam can bstan srung rgya mtsho’i rnam par thar pa cha shas tsam brjod pa sngon med legs bshad, Thimphu:

Kunzang Topgey, 1734; BDRC: W27414.

Sørensen, P.K., G. Hazod & T. Gyalbo, 2007. Rulers on the

Celestial Plain: Ecclesiastic and Secular Hegemony in Medieval Tibet: A Study of Tshal Gung-thang, 2 vols.,

Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Swami Venkatesananda, trans., 1988. The Concise Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki, Albany: State University of New York Press.

For use by the Author only | © 2019 Koninklijke Brill NV