Early Buddhist theory of knowledge (epistemology)

EARLY BUDDHIST THEORY OF KNOWLEDGE (EPISTEMOLOGY)

Three Indian Schools:

Traditionalists—appeal to the authority of scripture.

Rationalists—"innate" (inside the mind) ideas. Appeal to deductive argument. But any valid argument may have false premises.

Experientialists (Empiricism)—Hindu yogis had claimed to have found Atman= Brahman by direct experience. Rationalists rejected this claim. The Buddha rejected the jnana yoga claim that one is saved by knowledge (jnana) alone. For the Buddha knowledge is a means only not an an end in itself. Nevertheless, the Buddha is squarely within this camp, which is better named "experientialism" rather than "empiricism." Even David Hume, the arch Western empiricist, realized that there was more to empiricism than just the data of the five senses. For him as well as the Buddha internal experience was just as important as external experience.

ENGLISH AND BUDDHIST EMPIRICISM

"English" is a misnomer: John Locke was the only Englishman among them. David Hume was a Scotsman and George Berkeley was an Irishman. We’ll hear more about Berkeley when we talk about Yogacara Idealism later in the semester.

Let us emphasize the common ground between the Buddha and Hume:

1. Both of them thought that we should start with theory of knowledge first and then proceed to theory of reality. Without focusing first on what we can truly know, most philosophers are tempted to speculate on the nature of reality, form strong opinions, and then do their theory of knowledge later. Both the Buddha and Hume believe that this has led to incorrect beliefs in things that we cannot possibly know (God, atoms, souls, etc.).

2. Both had a fierce commitment to the empirical method. Hume, for example, rejected Locke and Berkeley as true, consistent empiricists. The Buddha was just a dogged in his determination to stick to experience and experience alone.

3. They both rejected the idea of eternal, unchanging substance of any type--material or spiritual

4. Both presented us with a bundle theory of the self.

But the differences are telling:

1. Hume claimed, much to the dismay of the scientists of his day, that we have no perception of causal relations. The Buddha, of course, claimed otherwise. Hume thought that causality was nothing but an habitual relation that we impose on experience.

2. No Buddhist equivalent to John Locke’s tabula rasa (mind as blank slate), because dispositions always carried over from previous life. Zen Buddhist "blank" mind or "no" mind is not equivalent either. Here the idea is to empty the mind of the "garbage" of ego formations.

The Buddha avoids skepticism in (3) and (4).

3. No problem of the "external world." Doctrine of internal relations holds that the thinking subject and its objects are always interdependent. John Locke thought there was a real world external to and independent from the one we perceived.

4. No "egocentric predicament." Thinking subjects are also internally related, so they are not isolated as Cartesian egos are. No problem of "other minds." Telepathy helps here!

In Buddhism the terms "subjectivism" as opposed to "objectivism" are meaningless. Descartes’ isolated ego cogito (thinking ego) is a fiction, an abstraction.

5. Emotion and feeling are inextricably fused in any act of knowledge.

6. From (5) it follows that fact and value will always be fused. At this point the Buddha parts company with David Hume, the Scottish empiricist most often compared with him.

7. ESP—major difference between Western and Eastern empiricists. Western empiricists would say that the Buddhists are really cheating empiricism by claiming such powers.

Except for ESP William James, the turn of the century Harvard psychologist and philosopher, is the closest Western empiricist to the Buddha. He agreed with him on causality, interdependence, and the unity of fact and value.

THE ORIGINS OF OBJECTIVISM ANDSUBJECTIVISM

Modernism also gave new meaning to what it means to be a subject, and the primary source of this innovation was the ego cogito of Descartes’ Meditations. The pre-Cartesian meaning of subject (Gk. hypokeimenon; Lat. subiectum) can still be seen in the "subjects" one takes in school or the "subject" of a sentence. In this ancient sense all things are subjects, things with "underlying (essential) kernels," as the Greek literally says and as Greek metaphysics proposed. (As opposed to substance metaphysics, the process view of this pansubjectivism makes all individuals subjects of some sort of experience.) After Cartesian doubt, however, there is only one subject of experience of which we are certain--viz., the human thinking subject. All other things in the world, including persons and other sentient beings, have now become objects of thought, not subjects in their own right. Cartesian subjectivism, therefore, gave birth simultaneously to modern objectivism as well. With the influence of the new mechanical cosmology, the stage was set for uniquely modern forms of otherness and alienation.

THE BUDDHA’S FOUR INDUCTIVE INFERENCES

1. Causality: "When this exists, that exists"—interdependent coorigination.

2. Impermanence—all things flow; all things are in flux

3. dukha—unsatisfactoriness (lit. sourness), the First Noble Truth. The Buddha here is drawing a moral inference from the fact of impermanence. He is doing what Hume thought one shouldn’t: drawing an "ought" from an "is."

4. Non-substantiality—no atman, no Brahman, no matter, no atoms, etc.

5. The Doctrine of Intentionality. Consciousness is always directed towards objects. (Added by Gier)

Notice that there is no mind or soul "behind" or to the left of the six faculties and no external objects to the right of the objects of sense. Clairvoyance and retrocognition and telepathy verify rebirth and the four Noble Truths. The chart is the sum total of Everything = "Reality."

KALUPAHANA , A HISTORY OF BUDDHIST PHILOSOPHY

CHAPTER III: KNOWLEDGE AND UNDERSTANDING

BUDDHIST EPISTEMOLOGY

Pre-Buddhist philosophical traditions, like western tradition, split between RATIONALISTS and EMPIRICISTS. The former believe that true knowledge is available prior to experience, while the latter believe that it is drawn mostly from experience.

RADICAL EMPIRICISM. There is a spectrum of possibilities ranging from extreme rationalists such as Plato, middle-of-the-roaders such as Aristotle, and "radical empiricists" like the Buddha, David Hume, and William James. Kalupahana has taken this term from William James, a Harvard psychologist-philosopher, with whom the Buddha, he claims, has many similarities. The B. has only superficial similarities with David Hume. They share a no-self, no-substance doctrine, but part company on causality, interdependence, and internal relations. Hume rejected all three. William James, however, agrees with all three of these plus being somewhat sympathetic to ESP.

YOGIC INSIGHT. Indian rationalists rejected yogic insight as a source of knowledge, while the empiricists included it. Buddhism follows the empiricist tradition on this point.

In the West it would have been a rationalist like Plato, who would have been most sympathetic to yogic insight. Plato's intuition of pure forms by the mind's "eye."

PHILOSOPHICAL PSYCHOLOGY

The Buddha emphasized psychological analysis to an extend not found in his contemporaries either East or West. One would have to go all the way to early modern western philosophy to find as much sophisticated philosophical psychology.

SENSE EXPERIENCE AS A SOURCE OF KNOWLEDGE

The meeting of VISUAL ORGAN, VISIBLE OBJECT, and CONSCIOUSNESS leads to CONTACT, from which arises FEELING.

WHAT ONE FEELS, ONE PERCEIVES; WHAT ONE PERCEIVES ONE REFLECTS ABOUT, ONE IS OBSESSED WITH.

As each of these elements of perception is dependent on the other, there is no room for ATMAN, an independent soul substance.

In the place of ATMAN, one has NAMARUPA, the psychophysical personality, which always carries over dispositions from a previous life.

This means that there can be no Buddhist equivalent of John Locke's TABULA RASA: a western empiricist idea of the mind as a blank slate.

NO PROBLEM OF THE EXTERNAL WORLD

Also contrary to the European tradition: the Buddha does not care to determine what the object world is in itself. For the Buddha there is no problem of the existence of the external world. It is a given, not made into a problem to be solved. The external world can be a problem only if it is conceived as existing independently of the subject. This of course is not the case in Buddhism.

The European quest for "objectivity" cannot be achieved because of the interdependence of everything.

The human subject and the object will always be together and never separate. Therefore, Descartes’ separate ego cogito, a pure thinking self, is a fiction, and impossible object, and a false starting point.

33: Kalup: "Where can the philosopher go to determine the nature of the object while avoiding the consciousness of the object?" Consciousness and objects always go together. There can be no point outside the world where one can view it "objectivity"--i.e., independently of a subject.

CENTRAL ROLE OF EMOTION

The introduction of feeling--i.e., pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral--is also very un-western. There is an irreducible emotive aspect to all experience. Any attempt to somehow eliminate it will be a failure.

FACT AND VALUE ALWAYS FUSED. This allows the Buddha to bring questions of FACT and VALUE together, two things, especially after the philosophy of David Hume, that western philosophy tried to keep apart.

WHAT ONE FEELS, ONE PERCEIVES

The Buddha realizes that how one feels affects one's perception; and conversely, how one conceives can affect how one feels.

34: REFLECTION "provides an opportunity to evaluate the consequences of perception, whether it leads to bondage and suffering or freedom and happiness."

Therefore, if one conceives of the self as unchanging and eternal, one then may very well become obsessed with and attached to such a concept. The concept of ATMAN leads to bondage, not freedom.

How does an "overstretched emotion" lead to the concept of ATMAN? A strong dislike for sensual pleasures, leading one to ascetic extremes and introspective extravagances??

Obsession is much more likely with conception, rather than perception, because the former endures, while the latter is fleeting.

34: Kalup: "It is easier to be enslaved by a concept that gives the impression of being permanent. . . than by a perception that is obviously temporal. . . ."

YOGIC INTUITION AS A SOURCE OF KNOWLEDGE

The Brahmanical (Hindu, Vedantist) tradition claimed to find ATMAN by yogic insight, so the Buddha had to prove that this was incorrect.

He learned yogic meditation from this first two teachers, but soon went on to perfect physical austerities--almost dying in a prolonged fast. He finally returned to meditation for his enlightenment under the Bodhi tree.

right concentration: samyak-samadhi

(Following Archie Bahm (The Philosophy of the Buddha rather than Kalup.)

first jhana (=trance): joy and ease, but thought--reflection and investigation--still continues.

second jhana: joy and ease continues, but reflection is negected. Internal dialogue stops.

third jnana: A double negation: no joy and ease; no reflection. One can become attached to joy and ease. This is the trap that the gods get into.

fourth jnana: A "four-fold negation": Neither no joy and ease; nor no reflection.

These are four preparatory stages of contemplation, still with body (rupa). The next four stages are without body (arupa), which are

1) perception of "boundless space";

2) perception of boundless space as consciousness--i.e., the perception of inward space;

3) consciousness of 2) perceived as emptiness [not shunyata, the later Sanskrit term, but the Pali akinei.

4) neither perception nor nonperception.

5) the complete cessation of sensation and perception

The Buddha claimed to have reached 1) and 2) under his first teachers, but attained all four later during his enlightenment. Kalup: the Buddha only followed the immaterial jhanas to check where previous yogis had gone. Is this is the reason why he returned to the Fourth Jhana to make his final exit?

Edward Conze describes this trance state (the ninth?): "Outwardly this state appears as one of coma. Motion, speech, and thought are absent. Only life and warmth remains. Even unconscious impulses are said to be asleep" (quoted in Kalup, 1976, p. 7).

When the Buddha reached this "Ninth" Jhana, Ananda thought that he was gone (Stryk, p. 46), but Anuruddha said that he was not. The Buddha then goes back down the trances, starts again and reaches Nirvana after the Fourth Jhana. This stage also must represent the end of craving as well.

As Kalup (1), 76, explains: There is still contact with objects in the Fourth; while in the Ninth there is none. so Nivrvana out of the Fourth is a greater achievement? Emphasis on human embodiment. A greater effort is required to reach Nirvana here? But, as we shall see, experience in either the Fourth or the Ninth is still differentiated. There is no union with a ultimate reality (as in some later Buddhist schools).

RETURNING TO THE FOURTH JHANA: Here one has reached a stage of complete equanimity, but no blank mind emptied of all conceptions.

Here the mind becomes extremely flexible, pliable, considerate(?), and without prejudices. ESP powers come into action at this point, or one can choose to go on to the higher jhanas.

Won't there always be reflection where there are concepts??

Kalup: here is the watershed in Buddhism between EMPIRICISM and TRANSCENDENTALISM. Kalup. stays with the first school, but most Mahayana Buddhism goes with the second.

With Buddhist empiricism concepts are still useful and need not be given up, whereas in Buddhist transcendentalism concepts must be given up as well. Zen Buddhist "blank" mind. Kalup. notes that the perception of space still requires concepts.

Kalup. is confident that the B. remained within empiricism and never denied the power of concepts to give us true knowledge.

Hindu and later Buddhist claims that one transcends the flux of experience and experiences a divine unity beyond concepts are not correct.

The highest concentration and contemplation does not lead to the discovery of some divine Self ATMAN that is identical to the Godhead BRAHMAN. Or a BUDDHA NATURE that is indistinguishable from the DHARMAKAYA (=body of the Buddha), as in some schools of Mahayana Buddhism.

38: The Buddha also preferred contemplation in the body, rather than out of the body. Does that mean the four highest jhanas are not really arupa? Or, it just means that he preferred to exit life at the Fourth Jhana to show the importance of embodiment. The B. used the highest states for relaxation and for confirming the nonsubstantiality of all things.

Psychophysical unity must be maintained or one commits, in Kalup's words, epistemological suicide.

40: Uses of ESP. TELEPATHY, RETROCOGNITION, AND CLAIRVOYANCE were most important for the B., especially the last two.

TELEPATHY: helped him understand his listeners and adapt his teachings to his audience.

RETROCOGNITION: Allowed him to size up a person's actions contextually and historically. HE WHO KNOWS CAUSALITY KNOWS THE DHARMA.

Is it really like a superextended memory with no prejudices and self-deception?

How can memory be pushed back into previous lives? (Discussed in Chapter VI.) Current claims about hypnotic regressions.

CLAIRVOYANCE: Kalup. repeats something we have already learned: this does not involve knowledge of the future.

But it is supposed to give the evolution of other persons through previous lives.

"With his clear paranormal clairvoyant vision he sees beings dying and being reborn, the low and the high, the fair and the ugly, the good and the evil each according to his karma" (Kalup, 1976, 44).

"Action (karma) is the field, consciousness the seed, and craving the moisture that leads to the rebirth of a being" (Kalup, 1976, p. 51).

NO PROBLEM OF OTHER MINDS

This ESP power allows the B. to eliminate another western (and sometimes eastern) problem--viz., the problem of other minds. The B. claimed to know them directly. But even without ESP the doctrine of interdependent coorigination would insure not only the existence of objects (the "problem" of the external world) but also the existence of other subjects (the "problem" of other minds).

THE BUDDHA'S "MIDDLE WAY" ON KNOWLEDGE CLAIMS

Kalup, 41: The skeptic, insisting on verifiability with normal senses, will reject these knowledge claims; while the "spiritualist" or "mystic" claims that there is something even more important beyond what the B. experiences.

The Buddha's Middle Way takes knowledge that is applicable to the relief of suffering and the cessation of craving--principally, knowledge of karma and rebirth.

42: ON THE USE OF THE WORD "MYSTIC." Kalup's use of the word "mystical" is troublesome. This word should be reserved for describing experiences of unity with the "One," the Godhead, or God. As the B. never claimed to have had any such experiences, it is not proper to call the B. a "mystic." See separate handout on mysticism.

If Kalup. means by "mystical" the word "ineffable," then that is the term he should use.

The highest knowledge--"knowledge of waning impulses"--is neither mystical nor ineffable. It is simply a perception of whether you are another person is free from craving.

ORGANIC HOLISM VS. MYSTICISM

Organic holism--as seen in Buddhism and contemporary physics--is too often mistaken as mysticism. In the former particularity is still maintained but in a system of internal (i.e., interdependent) relations; but in the latter all particularity is dissolved in an undifferentiated whole. This is not the view of early Buddhism or of contemporary physics. So early Buddhism and physics are most definitely not "mystical."

If things are externally related as are atoms are in classical atomism, the universe can be conceived of as a machine. But if things are internally related, then the universe can be conceived of as a living organism. Contemporary physics has brought us back to organic holism, not mysticism. Everything is not an undifferentiated one (nothing in physics points to that) but everything is an interdependent many.

59: Important to avoid talk of the "mysterious" (as any hidden secret) as well as the "mystical" (unity with some permanent divine substance). Searching for either will cause frustration and unease.

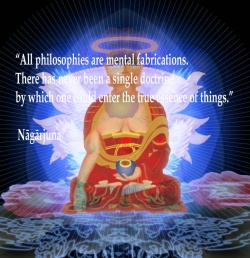

CONCLUSION: THE BUDDHA AVOIDS MYSTICISM, THE INEFFABLE, AND THE MYSTERIOUS. Radical empiricism simply gives us the facts that we need for spiritual liberation.

THE BUDDHA'S CLAIMS TO OMNISCIENCE

43: The Buddha is different from the Jain Mahavira and Hindu yogis, in whom omniscience is considered a divine attribute. If Kalup. is correct, this eliminates one of the reasons to propose a Buddhist TITANISM.

Titanism, as we shall see, is a radical form of human, in which human being claim, or have attributed to them, divine attributes. Only later Buddhists gave the B. divine attributes. He did not claim them himself.

The Pali terms literally mean "all-knowing" and "all-perceiving." The meaning of "all" is everything that is within the limits of experience, including ESP experience.

Hindu and Jain omniscience claimed knowledge of the future, because if one knew the ESSENCE (as enduring substance) of the past and present, then would know the future. Knowledge of non-enduring things is presumably not true knowledge. Hindu Vedanta: true knowledge is of ATMAN-BRAHMAN--all else is illusion.

But for the B. there are no enduring substances or essences, so this knowledge claim about the future is not true for him. Therefore, the Buddha's omniscience did not include knowledge of the future.

PREDICTION IS NOT FOREKNOWLEDGE. Prediction and prophecy about the future is not equivalent to actual knowledge of the future. Christian doctrine of divine foreknowledge on the basis of Hebrew prophecies. The latter are predictions, not actual knowledge of the future.

The so-called PROBLEM OF INDUCTION--that perception of many connected particulars will not give certainty of necessary relations among all particulars--does not exist for the B.--again because of the complete interdependence of experience. The problem exists only in philosophies--such as those found in Europe--where there are discrete entities externally related to one another--i.e., completely independent from one another.

Example: infinite number of atoms bouncing around in infinite space, which is the model for modern scientific thinking. As the atoms are completely independent from each other and their "relations" are completely "accidental" (i.e., they could always have been otherwise), then "even after the experience of a thousand instances, it is not possible to assume that the next instance will be similar."

EXTERNAL VS. INTERNAL RELATIONS

David Hume rejected the metaphysics of atoms, but he carried over external relations into perceptions, which he thought were also completely independent from one another. Hume said that induction was not possible because "inference from one event to another becomes impossible."

But if thing are internally related--i.e., interdependent--and one can perceive those relations, then inductive inference is not circular, but a proper inference to truth.

The Middle Way for Epistemology: between the extremes of skepticism--no knowledge is possible--and absolute knowledge (Hindu systems). Inductive knowledge from experience is the Buddha's Middle Way.