Stupas and temples: from the 1st century BC in India

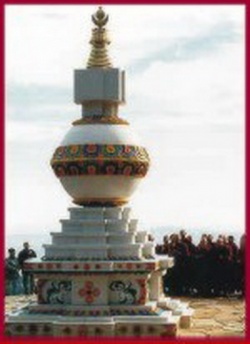

The most significant architectural feature of southeast Asia is the Buddhist stupa, known in India from the 1st century BC but no doubt dating from earlier. An architectural descendant of the burial mound, the stupa is a brick and plaster hemisphere with a pointed superstructure (seen as an image of the cosmos). Enshrining a relic of the Buddha, it serves as the sacred centre around which ritual occurs in an open-air setting.

The earliest surviving example is the Great Stupa at Sanchi, from the 1st century BC. Hinduism and Buddhism are closely interconnected at this stage. The stupa provides the architectural model for Hindu temples in India, for Buddhist temples in southeast Asia and for pagodas in China and Japan. Within India the simple shape of the early stupa evolves into the complex superstructure of later Hindu temples - rich in architectural ornament and often encrusted with teeming sculptures of deities and devils. Sometimes they are brightly painted to add to the sense of tumult.

Unlike the solid stupa, these structures rise above interior spaces which are used for worship. They are like steeples above churches, whereas the stupa is a massive inert reliquary at the centre of a temple complex.Buddhism and Hinduism spread together into southeast Asia, often to the same places at the same time. Both the solid stupa and the open temple can be found throughout the region.

The famous temples of Angkor Wat and Pagan in Cambodia and Burma, dating from around the 12th century, are in the open Hindu style. The massively tall gilded stupa at the centre of the Shwe Dagon temple in Rangoon (built as recently as the 19th century), is by contrast a solid structure in the original stupa tradition. Its interior chamber is designed only to house eight hairs of the Buddha.With the arrival of Buddhism in China, and subsequently Japan, the Indian architectural tradition undergoes another transformation. In the 2nd century Kanishka, a ruler in northwest India, builds a stupa in the form of a masonry tower to house some Buddhist relics. From this region Buddhism makes its way towards China along the Silk Road. Kanishka's tower proves a fruitful model.

In the hands of Chinese and Japanese carpenters, this type of stupa evolves into the tall and slender wooden pagoda. A superb example, from as early as AD 607, survives in Japan in the Horyuji temple at Nara.At much the same time as the wooden Japanese pagoda in the Horyuji temple, a stone version is created in northwest China. It is excavated and carved, on all four sides, from the solid rock of a cave at Yün-kang.

In achieving this laborious feat, the Chinese sculptors are following another ancient architectural tradition of India - that of enlarging natural caves into elaborately sculpted temples.

Just as human beings have always sheltered in caves, so they have often hollowed out more comfortable or impressive chambers where the rock is sufficiently soft. There are many examples of work of this kind, often done on a grand scale and involving intensive labour - though none has ever matched the earliest and most impressive of all, at Abu Simbel.

Religious devotion has been the main motive. Hindu, Buddhist and Christian communities have created temples or churches within the surrounding fabric of solid rock. They have even carved them with conventional architectural details, making them look as much as possible as if they have been built up in the normal way in stone.

India is the country with the greatest tradition of rock-cut temples, and all the region's three indigenous religions are involved. The earliest site is Ajanta, where elaborate pillared halls are carved into the rock - from an almost vertical cliff face - from about the 1st century BC to the 8th century AD.

The Ajanta caves are chiefly famous for their Buddhist murals, surviving from at least the 5th century AD. But the chaityas or meeting places are equally impressive, with their rows of carved columns and vaulted ceilings. Apart from the lack of any normal light (arriving, as it does, only from one end), the effect is that of a normal building. Ajanta is entirely Buddhist. The great columned cave temple of Elephanta, on an island near Bombay and dating from the 5th to 8th century AD, is exclusively Hindu - devoted to Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu. But the many cave temples of Ellora, spanning a longer period (from the 4th to 13th century), include shrines sacred to Buddhists, to Hindus and to Jains.

Ellora is a sloping site, which offers the opportunity for another architectural element. Open forecourts are carved here from the rock, with gateways and stone elephants and free-standing temples of two or three storeys in addition to the enclosed inner shrines.

Stupas were built of stones or bricks to commemorate important events or mark important places associated with Buddhism or to house important relics of Buddha. Ashok Maurya who laid the foundation of this group of monuments is said to have built 84,000 stupas, most of which have perished.

The best examples of stupas are those constructed at Amaravati, Sanchi, Barhut and Gaya. "One of the most striking architectural remains of ancient India" and the earliest and largest of the three stupas found in Sanchi was built by Ashoka (273-236 B.C.)

Sanchi in Raisen district of Madhya Pradesh is famous for its magnificent Buddhist monuments and edifices. Situated on a hill, these beautiful and well-preserved stupas depict the various stages of development of Buddhist art and arch1teeture over a period of thirteen hundred years from the third century B.C. to the twelfth century A.D. Inscriptions show that these monuments were maintained by the rich merchants of that region.

The stupa built by Ashoka was damaged during the break-up of the Maurya Empire. In the 2nd century B.C., during the. rule of the Sungas it was completely reconstructed. Religious activity led to the improvement and enlargement of the stupa and a stone railing was built around it. It was also embellished with the construction of heavily carved gateways.

The Great stupa has a large hemispherical dome which is flat at the top, and crowned by a triple umbrella or Chattra on a pedestal surrounded by a square railing or Karmika. Buddha's relics were placed in a casket chamber in the centre of the Dome. At the base of the dome is a high circular terrace probably meant for parikrama or circumambulation and an encircling balustrade. At the ground level is a stone-paved procession path and another stone Balustrade and two flights of steps leading to the circular terrace. Access to it is through four exquisitely carved gateways or Toranas in the North, South, East and West. The diameter of the stupa is 36.60 metres and its height is 16.46 metres. It is built of large burnt bricks and mud mortar. It is presumed that the elaborately carved Toranas were built by ivory or metal workers in the 1st. Century BC during the reign of King Satakarni of the Satavahana Dynasty. The last addition to the stupa was made during the early 4th Century AD in the Gupta period when four images of Buddha sitting in the dhyana mudra or meditation were installed at the four entrances.

The first Torana gateway to be built is the one at the principal entrance on the South. Each gateway has two square pillars. Crowning each pillar on. all four sides are four elephants, four lions and four dwarfs. The four dwarfs support a superstructure of three architraves or carved panels one above the other. Between these are intricately carved elephants and riders on horseback. The lowest architrave is supported on exquisitely carved bracket figures. The panels are decorated with finely carved figures of men, women, yakshas, lions and elephants. The entire panel of the gateways is covered with sculptured scenes from the life of Buddha, the Jataka Tales, events of the Buddhist times and rows of floral or lotus motifs. The scenes from Buddha's life show Buddha represented by symbols - the lotus, wheel a riderless caparisoned horse, an umbrella held above a throne, foot prints and the triratnas which are symbolic of Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. The top panel has a Dharma chakra with two Yakshas on either side holding chamaras. South of the Scenes depicted from Buddha's life are the Enlightenment of Buddha (a throne beneath a peepul tree); the First Sermon (a Dharma chakra placed on a throne); The Great Departure ( a riderless horse and an empty chariot with an umbrella above ); Sujata's offering and the temptation and assault by Mara.

The big Stupa at Bharhut also in Madhya Pradesh was constructed in the 2nd century BC in the Sunga Period. It is a hemispherical dome built of brick and is surmounted by a shaft and an umbrella to represent the spiritual sovereignty of Buddhism. The railing surrounding it is of red sandstone. Scenes from the life of Buddha and the Jataka Tales are sculptured on the gateways, pillars, uprights and cross-bars of the railings.

During the same period, a number of stupas, chaityas, viharas and pillars were constructed in Sanchi, Bodh-Gaya, Mathura, Gandharai and Nagarjunakonda. Though most of these have not remained in their entirety, the ruins are of architectural interest.

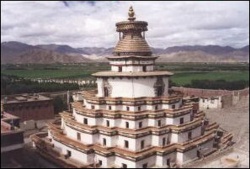

The Stupas of Nagajunakonda and Amaravati, both in the Guntur District of Andhra Pradesh show that the Stupas of the Southern region differ in structure from those of the North. The architecture here is a shift from the usual Buddhist style, which reflected the two main divisions in Buddhism - Hinayana and Mahayana. Different trends and styles were incorporated here giving rise to new architectural forms, i.e. a quadrangular monastery, square and rectangular image shrine, pillared hall and a. small stupa on a square platform.

The stupas of Nagarjunakonda are in the form of a hemispherical dome resting on a low drum encased in panels sculptured with scenes of events depicting the life of Buddha. A notable feature of the stupas here is ayaka platforms in the four directions with five inscribed pillars on each of them. The five pillars symbolise the five important events in the life of Buddha - his Birth, Renunciation, Enlightenment, First Sermon and Parinirvana.

Some of the stupas are built on a square platform having an apsidal shrine on either side and a pillared hall within a quadrangular monastery. Some stupas were wheel-shaped having four to ten spokes and a two or three winged vihara.

The earliest of the Nagarjunkonda stupas is the Maha Chaitya which contains the tooth relic of Buddha. The stupa is wheel-shaped with ayaka platforms surmounted by pillars. The smallest stupa here has only two cells and the Chaitya griha enshrines the image of Buddha.

Ruins of stupas have been found in Rajgriha or Rajgir (Bihar) where the First Buddhist Council was held; at Vaisali (Bihar) where the Second Buddhist Council was held and at Sravasti (U.P.) one of the eight places of Buddhist pilgrimage where Buddha is said to have performed the Great Miracle. To show his spiritual powers, he made a mango tree to sprout in a day and created numerous images of himself, sitting and standing on lotuses with fire and water emanating from his body. The conversion of King Prasenajit and the dacoit Angulimala is also said to have taken place here.

Ruins of the main stupa in Kusinagara in U.P. where Buddha passed away and was cremated, is believed to contain the bodily remains of Buddha. Both Fa-hien and Hiuen- Tsang have recorded their visits to these places. The Dhamekh Stupa and the Dharmarajika stupa at Sarnath are believed to have been built by Ashoka and later rebuilt in the Gupta period. These stupas contain the relics of Buddha and are therefore important places of Buddhist pilgrimage. Buddha gave his First Sermon in Sarnath and also founded the Sangha or Order of Monks here. The original Dhamekh Stupa built with mud or brick is a cylindrical structure 43.5 m. high. The stone basement has eight projecting faces with niches in them. Delicately carved with beautiful floral and geometrical patterns, it is believed to have been put up in thc Gupta period.

VIHARAS

Viharas or monasteries constructed with brick or excavated from rocks are found in different parts of India. Usually built to a set plan, they have a hall meant for congregational prayer with a running verandah on three sides or an open courtyard surrounded by a row of cells and a pillared verandah in front. These cells served as dwelling places for the monks. These monastic buildings built of bricks were self-contained units and had a Chaitya hall or Chaitya mandir attached to a stupa - the chief object of worship.

Some of the important Buddhist viharas are those at Ajanta, Ellora. Nasik, Karle, Kanheri, Bagh and Badami. The Hinayana viharas found in these places have many interesting features which differentiate them from the Mahayana type in the same regions. Though plain from the point of view of architecture, they are large ha1ls with cells excavated in the walls on three sides. The hall has one or more entrances. The small cells, each with a door have one or two stone platforms to serve as beds.

The excavations of viharas at Nagarjunakonda show large rectangular courtyards with stone-paved central halls. Around the courtyard, the row of cells, small and big, suggest residences and dining halls for monks.

Twenty-five of the rock-cut caves of Ajanta are viharas and are the finest of monasteries. Four of the viharas belong to the 2nd century BC. Later, other caves were excavated during the reign of the Vakataka rulers who were the contemporaries of the Gupta Rulers. Some of the most beautiful viharas belong to this period. The finest of them. Cave 1, of the Mahayana type consists of a verandah, a hall, groups of cells and a sanctuary. It has a decorated facade. The portico is supported by exquisitely carved pillars. The columns have a square base with figures of dwarfs and elaborately carved brackets and capitals. Below the capital is a square abacus with finely carved makara motifs. The walls and the ceilings of the cave contain the most exquisite paintings.

The viharas of Ellora dated 400 AD to 7th century AD are of one, two, and three storeys and are the largest of the type. They contain sculptured figures and belong to both Hinayana and Mahayana Buddhism.

CHAITYAS

Chaitya grihas or halls of worship were built all over the country either of brick or excavated from rocks. Ruins of a large number of structural Buddhist chaity grihas are found in the eastern districts of Andhra Pradesh, in valleys, near rivers and lakes. The ruins located in the districts of Srikakulam at Salihundam, of Visahkapatnam at Kotturu, of West Godavari at Guntapalli, of Krishna at Vijayawada, of Guntur at Nagajunakonda and Amaravati belong to the 3rd century BC and later. The largest brick chaitya hall was excavated at Guntapalli.

Some of the most beautiful rock-cut caves are those at Ajanta, ElIora, Bhaja, Karle, Bagh, Nasik and Kanheri. Some of the chunar sand-stone rock-cut chaityas of Bhaja. Kondane. Karle and Ajanta, all in Maharashtra state are earlier excavations and belong to the first phase or Hinayana creed of Buddhism and are similar to the brick and wooden structures of Ashokan times. Some of the chaityas show that wood had been used in the roofing and entrance arches. The chaitya at Bhaja is a long hall 16.75 metres long and 8 metres broad with an apse at the end. The hall is divided into a central nave and an aisle on either side flanked by two rows of pillars. The roof is vaulted. The rock-cut stupa in the apse is crowned by a wooden harmika. The chaitya has a large arched torana or entrance with an arched portico.

Hinayana rock architecture reaches the peak of excellence in the splendid chaitya at Karle. An inscription in Karle mentions Bhutapala, a banker to be the founder of the chaitya hall but later scholars identify him with Devabhuti, the last of the Sunga rulers.

The chaitya has a double-storeyed facade and has three doorways in the lower part. It has an upper gallery over which there is the usual arch. The walls of the vestibule to the chaitya hall are decorated with sculptured figures of couples. The pillars separating the central nave from the aisles have a pot base, an octagonal shaft, inverted lotus capital with an abacus. The abacus has exquisitely carved pairs of elephants kneeling down, each with a couple in front and caparisoned horses with riders on them. The stupa at the apse end is tall and cylindrical with two tiers of railings around the drum. It is crowned by the original wooden chhatra. This is the most beautiful of the chaityas.

The second phase of Buddhist architecture is marked by the Mahayana creed of Buddhism seen in some of the excellent rock-cut chaityas at Ajanta in Aurangabad district of Maharashtra excavated between 5th AD and 9th century AD during the rule of the Vakatakas, the Guptas and the Rashtrakutas.

The caves were first discovered in the beginning of the 19th century. The caves are excavated from a semi-circular steep rock with a stream flowing below, and were meant for the use of the monks who spent the rainy season there in meditation.

The caves are at different levels and have stairs leading down to the stream. Five of the thirty caves arc chaityas or sanctuaries. The earlier group of two caved dated 2nd century BC belong to the style of Kondan and Nasik caves.

The chaityas have a vaulted ceiling with a huge horse-shoe shaped window or chaitya window over the doorway. They are large halls divided into three, parts - the central nave, apse and aisles on either side separated by a row of columns. The side aisles continue behind the apse for circumambulation. At the centre of the apse is a rock stupa with large figure of Buddha, sitting or standing. A remarkable feature of these Chaityas is the imitation of woodwork on rock. Beams and rafters were carved in the rock though they serve no purpose. From the unfinished caves, we get an idea of the method of excavation. Starting from the ceiling, they worked downwards. Solid blocks were left to be carved into pillars. After finishing the verandah, they excavated the interior. Tools used were the pick-axe, chisel and hammer.

PAINTINGS

Paintings which has been an accepted art since early times attained heights of excellence in Gupta period. These exquisite paintings or frescos are to be seen in the caves of Ajanta. The entire surface of the caves is exquisitely painted and shows the high standard reached in mural painting.

The theme of the painting on the walls is mostly the life of Buddha and Bodhisattvas and the Jataka stories. These topics cover a continuous narration of events on all aspects of human- life from birth to death. Every kind of human emotion is depicted. The paintings reflect the contemporary life of the times, dress, ornaments, culture, weapons used, even their beliefs are portrayed with life-like reality. The paintings include gods, yakshas, kinneras, gandharvas, apsaras and human beings.

The paintings show their intense feeling for nature and an understanding of the various aspects of all living beings. The ceilings are covered with intricate designs, flowers, plants, birds, animals, fruit and people. The ground for painting was prepared by paving it with a rough layer of earth and sand mixed with vegetable fibres, husk and grass. A second coat of mud mixed with fine sand and fibrous vegetable material was applied. A final finish was given with a thin coat of lime-wash, glue was used as a binder. On this prepared surface, the outlines were drawn and the spaces were filled with the required colours; with much attention given to shades and tones. Red, yellow, black, ochre, blue and gypsum were mostly used.

Some of the renowned paintings are that of the Bodhisattva holding a lily (cave 1), the painting of Padmapani, the Apsaras with a turban headgear (cave 17) the painting on the ceiling (cave 2) and the toilet scheme (cave 17) considered to be a masterpiece of the painter. STHAMBAS

Sthambas or Pillars with religious emblems were put up by pious Buddhists in honour of Buddha or other great Buddhists. Fragments of sthambas belonging to Mauryan times and later were found at Sanchi, Sarnath, Amaravati and Nagarjunkonda.

A portion of the Ashoka Pillar, 15.25 metres high, surmounted by the famous lion-capital and a dharma chakra above the heads of the four lions stands embedded near the Dharmarajika stupa at Sarnath. The pillar bears the edict of Ashoka warning the monks and nuns against creating a schism in the monastic order. The broken fragments of the Pillar are now in the Museum at Sarnath. The lion-capital - the most

magnificient piece of Mauryan sculpture is 2.31 metres high. It consists of four parts - (i) a bell-shaped vase covered with inverted lotus petals, (ii) a round abacus, (iii) four seated lions and (iv) a crowning dharmachakra with thirty two spokes. The four lions are beautifully sculptured. On the abacus are four running animals - an elephant, a bull, a horse and a. lion with a small dharmachakra between them. The dharmachakra symbolises the dharma or law; the four lions facing the four directions are the form of Buddha or Sakyasimha, the four galloping animals are the four quarters according to Buddhist books and the four smaller dharmachakras stand for the intermediate regions and the lotus is the symbol of creative activity. The surface of these pillars has a mirror like finish. Another Ashokan Pillar of note is the one at Lauriya Nandangarh in Bihar. Erected in the 3rd century BC it is made of highly polished Chunar sand-stone. Standing 9.8 metres high it rises from the ground and has no base structure. It is surmounted by a bell-shaped inverted lotus. The abacus on it is decorated with flying geese and crowning it is a sitting lion. The pillar is an example of the engineering skill of the craftsmen of Mauryan times.