Difference between revisions of "Thangka"

| (6 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

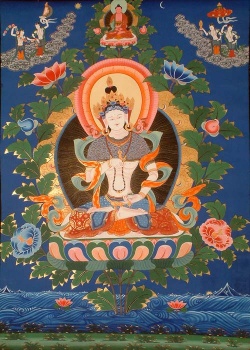

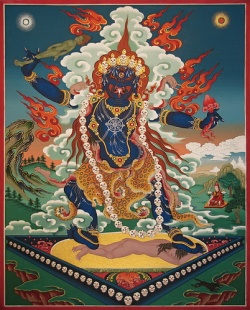

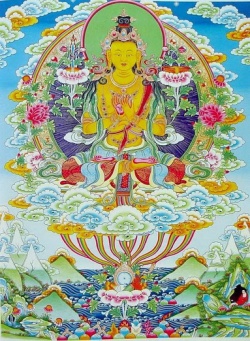

| − | [[File:VaisravanaVV.jpg|thumb|250px|Vaisravana by [[Vello Vaartnou]] | + | [[File:VaisravanaVV.jpg|thumb|250px|Vaisravana by [[Vello Vaartnou]])] |

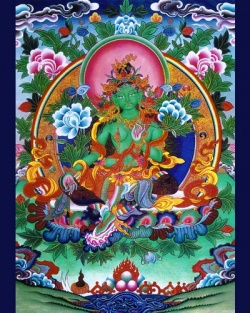

| − | [[File:Guru-Naistega.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Padmasambhava]] by [[Vello Vaartnou]]] | + | [[File:Guru-Naistega.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Padmasambhava]] by [[Vello Vaartnou]])]<nomobile>{{DisplayImages|1975|1151|1842|273|307|1755}}</nomobile> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{Wiki|Historians}} note that {{Wiki|Chinese}} painting had a profound [[influence]] on [[Tibetan]] painting in general. Starting from the 14th and 15th century, [[Tibetan]] painting had incorporated many [[elements]] from the {{Wiki|Chinese}}, and during the 18th century, {{Wiki|Chinese}} painting had a deep and far-stretched impact on [[Tibetan]] [[visual]] [[art]]. According to {{Wiki|Giuseppe Tucci}}, by the [[time]] of the {{Wiki|Qing Dynasty}}, "a new [[Tibetan]] [[art]] was then developed, which in a certain [[sense]] was a provincial {{Wiki|echo}} of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} 18th century's smooth ornate preciosity." | + | A [[thangka]], also known as [[tangka]], [[thanka]] or [[tanka]] ({{Wiki|Nepali}} pronunciation: [ˈt̪ʰaŋka]; [[Tibetan]]: {{BigTibetan|[[ཐང་ཀ་]]}}; [[Nepal]] [[Bhasa]]: [[पौभा]]) is a painting on {{Wiki|silk}} with {{Wiki|embroidery}}, usually depicting a [[Buddhist]] [[deity]], scene, or [[mandala]] of some sort. |

| + | |||

| + | The [[thankga]] is not a flat creation like an oil painting or acrylic painting but consists of a picture panel which is painted or embroidered over which a textile is mounted and then over which is laid a cover, usually {{Wiki|silk}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Generally, [[thangkas]] last a very long [[time]] and retain much of their lustre, but because of their delicate [[nature]], they have to be kept in dry places where {{Wiki|moisture}} won't affect the [[quality]] of the {{Wiki|silk}}. It is sometimes called a scroll-painting. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These [[thangka]] served as important [[teaching]] tools depicting the [[life]] of the [[Buddha]], various influential [[lamas]] and other [[deities]] and [[bodhisattvas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One [[subject]] is The [[Wheel of Life]], which is a [[visual]] [[representation]] of the [[Abhidharma]] teachings ([[Art]] of [[Enlightenment]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Thangka]], when created properly, perform several different functions. Images of [[deities]] can be used as [[teaching]] tools when depicting the [[life]] (or [[lives]]) of the [[Buddha]], describing historical events concerning important [[Lamas]], or retelling [[myths]] associated with other [[deities]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Devotional images act as the centerpiece during a [[ritual]] or {{Wiki|ceremony}} and are often used as mediums through which one can offer [[prayers]] or make requests. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Overall, and perhaps most importantly, [[religious]] [[art]] is used as a [[meditation]] tool to help bring one further down the [[path]] to [[enlightenment]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Buddhist]] [[Vajrayana practitioner]] uses a [[thankga]] image of their [[yidam]], or [[meditation deity]], as a [[guide]], by [[visualizing]] “themselves as [[being]] that [[deity]], thereby internalizing the [[Buddha]] qualities (Lipton, [[Ragnubs]]).” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|Historians}} note that {{Wiki|Chinese}} painting had a profound [[influence]] on [[Tibetan]] painting in general. Starting from the 14th and 15th century, [[Tibetan]] painting had incorporated many [[elements]] from the {{Wiki|Chinese}}, and during the 18th century, {{Wiki|Chinese}} painting had a deep and far-stretched impact on [[Tibetan]] [[visual]] [[art]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to {{Wiki|Giuseppe Tucci}}, by the [[time]] of the {{Wiki|Qing Dynasty}}, "a new [[Tibetan]] [[art]] was then developed, which in a certain [[sense]] was a provincial {{Wiki|echo}} of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} 18th century's smooth ornate preciosity." | ||

| + | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | [[Thangka]] is a {{Wiki|Nepalese}} [[art]] [[form]] exported to [[Tibet]] after [[Princess Bhrikuti]] of [[Nepal]], daughter of [[King]] Lichchavi, [[married]] [[Songtsän Gampo]], the [[ruler]] of [[Tibet]] imported the images of [[Arya awalokiteshwara]] and other {{Wiki|Nepalese}} [[deities]] to [[Tibet]]. History of [[thangka]] Paintings in [[Nepal]] began in 11th century A.D. when [[Buddhists]] and [[Hindus]] began to make illustration of the [[deities]] and natural scenes. Historically, [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[influence]] in {{Wiki|Nepalese}} paintings is quite evident in [[Paubhas]] ([[Thangkas]]). [[Paubhas]] are of two types, the [[Palas]] which are illustrative paintings of the [[deities]] and the [[Mandala]], which are {{Wiki|mystic}} diagrams paintings of complex test prescribed patterns of circles an square each having specific significance. It was through [[Nepal]] that [[Mahayana Buddhism]] was introduced into [[Tibet]] during [[ | + | [[Thangka]] is a {{Wiki|Nepalese}} [[art]] [[form]] exported to [[Tibet]] after [[Princess Bhrikuti]] of [[Nepal]], daughter of [[King]] [[Lichchavi]], [[married]] [[Songtsän Gampo]], the [[ruler]] of [[Tibet]] imported the images of [[Arya awalokiteshwara]] and other {{Wiki|Nepalese}} [[deities]] to [[Tibet]]. |

| + | |||

| + | History of [[thangka]] Paintings in [[Nepal]] began in 11th century A.D. when [[Buddhists]] and [[Hindus]] began to make illustration of the [[deities]] and natural scenes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Historically, [[Tibetan]] and {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[influence]] in {{Wiki|Nepalese}} paintings is quite evident in [[Paubhas]] ([[Thangkas]]). | ||

| + | |||

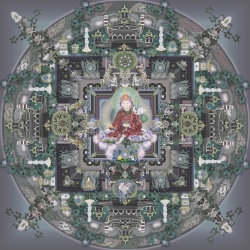

| + | [[Paubhas]] are of two types, the [[Palas]] which are illustrative paintings of the [[deities]] and the [[Mandala]], which are {{Wiki|mystic}} diagrams paintings of complex test prescribed patterns of circles an square each having specific significance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It was through [[Nepal]] that [[Mahayana Buddhism]] was introduced into [[Tibet]] during reign of [[Angshuvarma]] in the seventh century A.D. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There was therefore a great demand for [[religious]] icons and [[Buddhist]] [[manuscripts]] for newly built [[monasteries]] throughout [[Tibet]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A number of [[Buddhist]] [[manuscripts]], [[including]] [[Prajnaparamita]], were copied in {{Wiki|Kathmandu}} Valley for these [[monasteries]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita]] for example, was copied in {{Wiki|Patan}} in the year 999 A.D., during the reign of [[Narendra Dev]] and [[Udaya Deva]], for the [[Sakya monastery]] in [[Tibet]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the Nor [[monastery]] in [[Tibet]], two copies were made in [[Nepal]]-one of [[Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita]] in 1069 A.D. and the other of [[Kavyadarsha]] in 1111 A.D. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[influence]] of {{Wiki|Nepalese}} [[art]] extended till [[Tibet]] and even [[beyond]] in [[China]] in regular [[order]] during the thirteenth century. | ||

| − | + | {{Wiki|Nepalese}} artisans were dispatched to the courts of {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[emperors]] at their request to perform their workmanship and impart expert [[knowledge]]. | |

| − | [[Religious]] paintings worshipped as icons are known as [[Paubha]] in [[Newari]] and [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] in [[Tibetan]]. The origin of [[Paubha]] or [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] paintings may be attributed to the {{Wiki|Nepalese}} {{Wiki|artists}} responsible for creating a number of special metal works and wall- paintings as well as [[illuminated]] [[manuscripts]] in [[Tibet]]. [[Realizing]] the great demand for [[religious]] icons in [[Tibet]], these {{Wiki|artists}}, along with [[monks]] and traders, took with them from [[Nepal]] not only metal sculptures but also a number of [[Buddhist]] [[manuscripts]]. To better fulfill the ever - increasing demand {{Wiki|Nepalese}} {{Wiki|artists}} [[initiated]] a new type of [[religious]] painting on cloth that could be easily rolled up and carried along with them. This type of painting became very popular both in [[Nepal]] and [[Tibet]] and so a new school of [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] painting evolved as early as the ninth or tenth century and has remained popular to this day. One of the earliest specimens of {{Wiki|Nepalese}} [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] painting dates from the thirteenth /fourteenth century and shows [[Amitabha]] surrounded by [[Bodhisattva]]. Another | + | The exemplary contribution made by the artisans of [[Nepal]], specially by the {{Wiki|Nepalese}} innovator and {{Wiki|architect}} [[Balbahu]], known by his popular [[name]] [[Araniko]] bear testimony to this fact even today. |

| + | |||

| + | After the introduction of paper, palm leaf became less popular, however, it continued to be used until the eighteenth century. Paper [[manuscripts]] imitated the oblong [[shape]] but were wider than the palm leaves. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | From the fifteenth century onward, brighter colors gradually began to appear in {{Wiki|Nepalese}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Because of the growing importance of the [[Tantric]] {{Wiki|cult}}, various aspects of {{Wiki|Shiva}} and [[Shakti]] were painted in [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] poses. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Mahakala]], [[Manjushri]], [[Lokeshwara]] and other [[deities]] were equally popular and so were also frequently represented in [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] paintings of later dates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As [[Tantrism]] [[embodies]] the [[ideas]] of [[esoteric]] [[power]], [[magic]] forces, and a great variety of [[symbols]], strong {{Wiki|emphasis}} is laid on the {{Wiki|female}} [[element]] and {{Wiki|sexuality}} in the paintings of that period. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Religious]] paintings [[worshipped]] as icons are known as [[Paubha]] in [[Newari]] and [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] in [[Tibetan]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The origin of [[Paubha]] or [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] paintings may be attributed to the {{Wiki|Nepalese}} {{Wiki|artists}} responsible for creating a number of special metal works and wall- paintings as well as [[illuminated]] [[manuscripts]] in [[Tibet]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Realizing]] the great demand for [[religious]] icons in [[Tibet]], these {{Wiki|artists}}, along with [[monks]] and traders, took with them from [[Nepal]] not only metal sculptures but also a number of [[Buddhist]] [[manuscripts]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To better fulfill the ever - increasing demand {{Wiki|Nepalese}} {{Wiki|artists}} [[initiated]] a new type of [[religious]] painting on cloth that could be easily rolled up and carried along with them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This type of painting became very popular both in [[Nepal]] and [[Tibet]] and so a new school of [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] painting evolved as early as the ninth or tenth century and has remained popular to this day. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the earliest specimens of {{Wiki|Nepalese}} [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] painting dates from the thirteenth /fourteenth century and shows [[Amitabha]] surrounded by [[Bodhisattva]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another [[Nepalese Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] with three dates in the inscription (the last one [[corresponding]] to 1369 A.D.), is one of the earliest known [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] with {{Wiki|inscriptions}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The "[[Mandala]] of [[Vishnu]] " dated 1420 A.D., is another fine example of the painting of this period. Early {{Wiki|Nepalese}} [[Thangkas]] are simple in design and composition. | ||

| + | |||

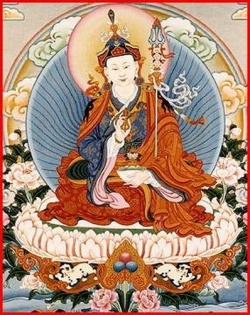

| + | The main [[deity]], a large figure, occupies the central position while surrounded by smaller figures of lesser [[divinities]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] painting is one of the major [[science]] out the five major and five minor fields of [[knowledge]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Its origin can be traced all the way back to the [[time]] of [[Lord]] [[Buddha]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The main themes of [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] paintings are [[religious]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | During the reign of [[Tibetan]] [[Dharma King]] [[Trisong Duetsen]] the [[Tibetan]] [[masters]] refined their already well developed [[arts]] through research and studies of different country's [[tradition]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Thanka]] painting's lining and measurement, costumes, implementations and ornaments are mostly based on [[Indian]] styles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The drawing of figures are based on {{Wiki|Nepalese}} style and the background sceneries are based on {{Wiki|Chinese}} style. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Thus]], the [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] paintings became a unique and {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[art]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although the practice of [[thanka]] painting was originally done as a way of gaining [[merit]] it has nowadays only evolved into a [[money]] making business and the [[noble]] {{Wiki|intentions}} it once carried has been diluted. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Tibetans]] do not sell [[Thangkas]] on a large scale as the selling of [[religious]] {{Wiki|artifacts}} such as [[thangkas]] and {{Wiki|idols}} is frowned upon in the [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|community}} and thus non [[Tibetan]] groups have been able to monopolize on it's ([[thangka's]]) [[popularity]] among [[Buddhist]] and [[art]] enthusiasts from the [[west]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Thanka]] / [[Thangka]] have developed in the northern [[Himalayan]] regions among the [[Lamas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Besides [[Lamas]], [[Gurung]] and [[Tamang]] communities are also producing [[Tankas]], which provide substantial employment opportunities for many [[people]] in the hills. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Newari]] [[Thankas]] (Also known as [[Paubha]]) has been the hidden [[art]] work in {{Wiki|Kathmandu}} valley from 13th century. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We have preserved this [[art]] and are exclusively creating this with some particular painter [[family]] who have inherited their [[art]] from their forefathers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some of the artistic [[religious]] and historical paintings are also done by the [[Newars]] of {{Wiki|Kathmandu}} Valley. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Types== | ==Types== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Based on technique and material, [[thangkas]] can be grouped by types. Generally, they are divided into two broad categories: those that are painted (Tib.) [[bris-tan]]—and those made of {{Wiki|silk}}, either by appliqué or {{Wiki|embroidery}}. | Based on technique and material, [[thangkas]] can be grouped by types. Generally, they are divided into two broad categories: those that are painted (Tib.) [[bris-tan]]—and those made of {{Wiki|silk}}, either by appliqué or {{Wiki|embroidery}}. | ||

| + | |||

[[Thangkas]] are further divided into these more specific categories: | [[Thangkas]] are further divided into these more specific categories: | ||

| + | |||

* [[Painted in colors]] (Tib.) [[tson-tang]]—the most common type | * [[Painted in colors]] (Tib.) [[tson-tang]]—the most common type | ||

| Line 35: | Line 149: | ||

* [[Red Background]]—literally {{Wiki|gold}} line, but referring to {{Wiki|gold}} line on a {{Wiki|vermillion}} (Tib.) [[mar-tang]] | * [[Red Background]]—literally {{Wiki|gold}} line, but referring to {{Wiki|gold}} line on a {{Wiki|vermillion}} (Tib.) [[mar-tang]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | Somewhat related are [[Tibetan]] tsakli, which look like miniature [[thangkas]], but are usually used as [[initiation]] cards or [[offerings]]. | + | |

| + | Whereas typical [[thangkas]] are fairly small, between about 18 and 30 inches tall or wide, there are also giant {{Wiki|festival}} [[thangkas]], usually [[Appliqué]], and designed to be unrolled against a wall in a [[monastery]] for particular [[religious]] occasions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These are likely to be wider than they are tall, and may be sixty or more feet across and perhaps twenty or more high. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Somewhat related are [[Tibetan]] [[tsakli]], which look like miniature [[thangkas]], but are usually used as [[initiation]] cards or [[offerings]]. | ||

Because [[Thangkas]] can be quite expensive, [[people]] nowadays use posters of [[Thangkas]] as an alternative to the {{Wiki|real}} [[thangkas]] for [[religious]] purposes. | Because [[Thangkas]] can be quite expensive, [[people]] nowadays use posters of [[Thangkas]] as an alternative to the {{Wiki|real}} [[thangkas]] for [[religious]] purposes. | ||

| + | |||

==Process== | ==Process== | ||

| − | |||

| − | The composition of a [[thangka]], as with the majority of [[Buddhist]] [[art]], is highly geometric. Arms, {{Wiki|legs}}, [[eyes]], nostrils, {{Wiki|ears}}, and various [[ritual]] implements are all laid out on a systematic grid of angles and intersecting lines. A [[skilled]] [[thangka]] artist will generally select from a variety of predesigned items to include in the composition, ranging from [[alms bowls]] and [[animals]], to the [[shape]], size, and angle of a figure's [[eyes]], {{Wiki|nose}}, and lips. The process seems very methodical, but often requires deep [[understanding]] of the [[symbolism]] involved to capture the [[spirit]] of it. | + | [[Thangkas]] are painted on cotton or {{Wiki|silk}}. |

| + | |||

| + | The most common is a loosely woven cotton produced in widths from 40 to 58 centimeters (16 - 23 inches). | ||

| + | |||

| + | While some variations do [[exist]], [[thangkas]] wider than 45 centimeters (17 or 18 inches) frequently have seams in the support. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The paint consists of pigments in a [[water]] soluble {{Wiki|medium}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Both mineral and organic pigments are used, tempered with a herb and [[glue]] {{Wiki|solution}}. In {{Wiki|Western}} {{Wiki|terminology}}, this is a distemper technique. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The composition of a [[thangka]], as with the majority of [[Buddhist]] [[art]], is highly geometric. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Arms, {{Wiki|legs}}, [[eyes]], nostrils, {{Wiki|ears}}, and various [[ritual]] implements are all laid out on a systematic grid of angles and intersecting lines. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A [[skilled]] [[thangka]] artist will generally select from a variety of predesigned items to include in the composition, ranging from [[alms bowls]] and [[animals]], to the [[shape]], size, and angle of a figure's [[eyes]], {{Wiki|nose}}, and lips. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The process seems very methodical, but often requires deep [[understanding]] of the [[symbolism]] involved to capture the [[spirit]] of it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Thangka]] often overflow with [[symbolism]] and allusion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because the [[art]] is explicitly [[religious]], all [[symbols]] and {{Wiki|allusions}} must be in accordance with strict guidelines laid out in [[Buddhist scripture]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The artist must be properly trained and have sufficient [[religious]] [[understanding]], [[knowledge]], and background to create an accurate and appropriate [[thangka]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lipton and [[Ragnubs]] clarify this in [[Treasures]] of [[Tibetan]] [[Art]]: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “[[Tibetan]] [[art]] exemplifies the [[nirmanakaya]], the [[physical body]] of [[Buddha]], and also the qualities of the [[Buddha]], perhaps in the [[form]] of a [[deity]]. | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Art]] [[objects]], therefore, must follow {{Wiki|rules}} specified in the [[Buddhist scriptures]] regarding proportions, [[shape]], {{Wiki|color}}, stance, hand positions, and [[attributes]] in [[order]] to personify correctly the [[Buddha]] or [[Deities]].” |

| − | |||

==Gallery== | ==Gallery== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

{|cellpadding="8" style="text-align: center;" | {|cellpadding="8" style="text-align: center;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

Latest revision as of 11:57, 31 October 2023

[[File:VaisravanaVV.jpg|thumb|250px|Vaisravana by Vello Vaartnou)]

[[File:Guru-Naistega.jpg|thumb|250px|Padmasambhava by Vello Vaartnou)]

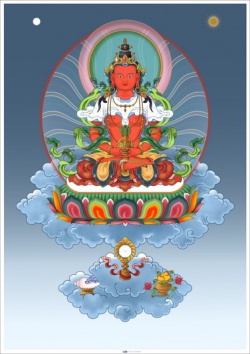

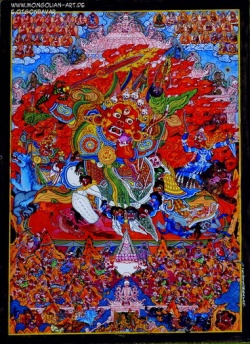

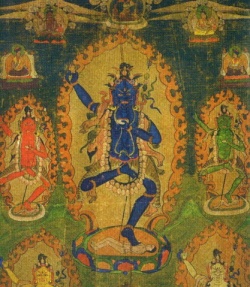

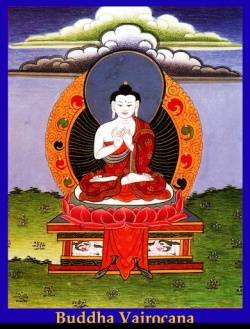

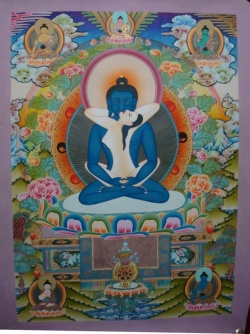

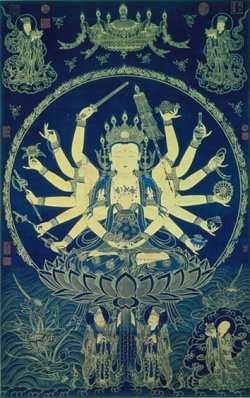

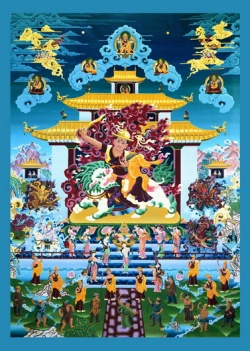

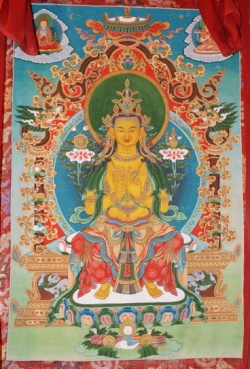

A thangka, also known as tangka, thanka or tanka (Nepali pronunciation: [ˈt̪ʰaŋka]; Tibetan: ཐང་ཀ་; Nepal Bhasa: पौभा) is a painting on silk with embroidery, usually depicting a Buddhist deity, scene, or mandala of some sort.

The thankga is not a flat creation like an oil painting or acrylic painting but consists of a picture panel which is painted or embroidered over which a textile is mounted and then over which is laid a cover, usually silk.

Generally, thangkas last a very long time and retain much of their lustre, but because of their delicate nature, they have to be kept in dry places where moisture won't affect the quality of the silk. It is sometimes called a scroll-painting.

These thangka served as important teaching tools depicting the life of the Buddha, various influential lamas and other deities and bodhisattvas.

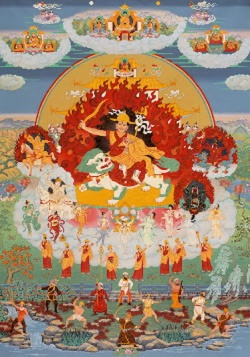

One subject is The Wheel of Life, which is a visual representation of the Abhidharma teachings (Art of Enlightenment).

Thangka, when created properly, perform several different functions. Images of deities can be used as teaching tools when depicting the life (or lives) of the Buddha, describing historical events concerning important Lamas, or retelling myths associated with other deities.

Devotional images act as the centerpiece during a ritual or ceremony and are often used as mediums through which one can offer prayers or make requests.

Overall, and perhaps most importantly, religious art is used as a meditation tool to help bring one further down the path to enlightenment.

The Buddhist Vajrayana practitioner uses a thankga image of their yidam, or meditation deity, as a guide, by visualizing “themselves as being that deity, thereby internalizing the Buddha qualities (Lipton, Ragnubs).”

Historians note that Chinese painting had a profound influence on Tibetan painting in general. Starting from the 14th and 15th century, Tibetan painting had incorporated many elements from the Chinese, and during the 18th century, Chinese painting had a deep and far-stretched impact on Tibetan visual art.

According to Giuseppe Tucci, by the time of the Qing Dynasty, "a new Tibetan art was then developed, which in a certain sense was a provincial echo of the Chinese 18th century's smooth ornate preciosity."

History

Thangka is a Nepalese art form exported to Tibet after Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal, daughter of King Lichchavi, married Songtsän Gampo, the ruler of Tibet imported the images of Arya awalokiteshwara and other Nepalese deities to Tibet.

History of thangka Paintings in Nepal began in 11th century A.D. when Buddhists and Hindus began to make illustration of the deities and natural scenes.

Historically, Tibetan and Chinese influence in Nepalese paintings is quite evident in Paubhas (Thangkas).

Paubhas are of two types, the Palas which are illustrative paintings of the deities and the Mandala, which are mystic diagrams paintings of complex test prescribed patterns of circles an square each having specific significance.

It was through Nepal that Mahayana Buddhism was introduced into Tibet during reign of Angshuvarma in the seventh century A.D.

There was therefore a great demand for religious icons and Buddhist manuscripts for newly built monasteries throughout Tibet.

A number of Buddhist manuscripts, including Prajnaparamita, were copied in Kathmandu Valley for these monasteries.

Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita for example, was copied in Patan in the year 999 A.D., during the reign of Narendra Dev and Udaya Deva, for the Sakya monastery in Tibet.

For the Nor monastery in Tibet, two copies were made in Nepal-one of Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita in 1069 A.D. and the other of Kavyadarsha in 1111 A.D.

The influence of Nepalese art extended till Tibet and even beyond in China in regular order during the thirteenth century.

Nepalese artisans were dispatched to the courts of Chinese emperors at their request to perform their workmanship and impart expert knowledge.

The exemplary contribution made by the artisans of Nepal, specially by the Nepalese innovator and architect Balbahu, known by his popular name Araniko bear testimony to this fact even today.

After the introduction of paper, palm leaf became less popular, however, it continued to be used until the eighteenth century. Paper manuscripts imitated the oblong shape but were wider than the palm leaves.

From the fifteenth century onward, brighter colors gradually began to appear in Nepalese.

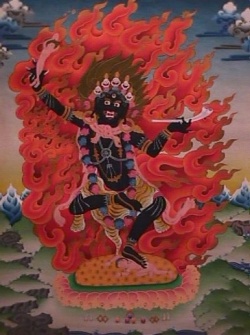

Because of the growing importance of the Tantric cult, various aspects of Shiva and Shakti were painted in conventional poses.

Mahakala, Manjushri, Lokeshwara and other deities were equally popular and so were also frequently represented in Thanka / Thangka paintings of later dates.

As Tantrism embodies the ideas of esoteric power, magic forces, and a great variety of symbols, strong emphasis is laid on the female element and sexuality in the paintings of that period.

Religious paintings worshipped as icons are known as Paubha in Newari and Thanka / Thangka in Tibetan.

The origin of Paubha or Thanka / Thangka paintings may be attributed to the Nepalese artists responsible for creating a number of special metal works and wall- paintings as well as illuminated manuscripts in Tibet.

Realizing the great demand for religious icons in Tibet, these artists, along with monks and traders, took with them from Nepal not only metal sculptures but also a number of Buddhist manuscripts.

To better fulfill the ever - increasing demand Nepalese artists initiated a new type of religious painting on cloth that could be easily rolled up and carried along with them.

This type of painting became very popular both in Nepal and Tibet and so a new school of Thanka / Thangka painting evolved as early as the ninth or tenth century and has remained popular to this day.

One of the earliest specimens of Nepalese Thanka / Thangka painting dates from the thirteenth /fourteenth century and shows Amitabha surrounded by Bodhisattva.

Another Nepalese Thanka / Thangka with three dates in the inscription (the last one corresponding to 1369 A.D.), is one of the earliest known Thanka / Thangka with inscriptions.

The "Mandala of Vishnu " dated 1420 A.D., is another fine example of the painting of this period. Early Nepalese Thangkas are simple in design and composition.

The main deity, a large figure, occupies the central position while surrounded by smaller figures of lesser divinities.

Thanka / Thangka painting is one of the major science out the five major and five minor fields of knowledge.

Its origin can be traced all the way back to the time of Lord Buddha.

The main themes of Thanka / Thangka paintings are religious.

During the reign of Tibetan Dharma King Trisong Duetsen the Tibetan masters refined their already well developed arts through research and studies of different country's tradition.

Thanka painting's lining and measurement, costumes, implementations and ornaments are mostly based on Indian styles.

The drawing of figures are based on Nepalese style and the background sceneries are based on Chinese style.

Thus, the Thanka / Thangka paintings became a unique and distinctive art.

Although the practice of thanka painting was originally done as a way of gaining merit it has nowadays only evolved into a money making business and the noble intentions it once carried has been diluted.

Tibetans do not sell Thangkas on a large scale as the selling of religious artifacts such as thangkas and idols is frowned upon in the Tibetan community and thus non Tibetan groups have been able to monopolize on it's (thangka's) popularity among Buddhist and art enthusiasts from the west.

Thanka / Thangka have developed in the northern Himalayan regions among the Lamas.

Besides Lamas, Gurung and Tamang communities are also producing Tankas, which provide substantial employment opportunities for many people in the hills.

Newari Thankas (Also known as Paubha) has been the hidden art work in Kathmandu valley from 13th century.

We have preserved this art and are exclusively creating this with some particular painter family who have inherited their art from their forefathers.

Some of the artistic religious and historical paintings are also done by the Newars of Kathmandu Valley.

Types

Based on technique and material, thangkas can be grouped by types. Generally, they are divided into two broad categories: those that are painted (Tib.) bris-tan—and those made of silk, either by appliqué or embroidery.

Thangkas are further divided into these more specific categories:

- Painted in colors (Tib.) tson-tang—the most common type

- Appliqué (Tib.) go-tang

- Black Background—meaning gold line on a black background (Tib.) nagtang

- Blockprints—paper or cloth outlined renderings, by woodcut/woodblock printing

- Embroidery (Tib.) tsem-thang

- Gold Background—an auspicious treatment, used judiciously for peaceful, long-life deities and fully enlightened buddhas

- Red Background—literally gold line, but referring to gold line on a vermillion (Tib.) mar-tang

Whereas typical thangkas are fairly small, between about 18 and 30 inches tall or wide, there are also giant festival thangkas, usually Appliqué, and designed to be unrolled against a wall in a monastery for particular religious occasions.

These are likely to be wider than they are tall, and may be sixty or more feet across and perhaps twenty or more high.

Somewhat related are Tibetan tsakli, which look like miniature thangkas, but are usually used as initiation cards or offerings.

Because Thangkas can be quite expensive, people nowadays use posters of Thangkas as an alternative to the real thangkas for religious purposes.

Process

Thangkas are painted on cotton or silk.

The most common is a loosely woven cotton produced in widths from 40 to 58 centimeters (16 - 23 inches).

While some variations do exist, thangkas wider than 45 centimeters (17 or 18 inches) frequently have seams in the support.

The paint consists of pigments in a water soluble medium.

Both mineral and organic pigments are used, tempered with a herb and glue solution. In Western terminology, this is a distemper technique.

The composition of a thangka, as with the majority of Buddhist art, is highly geometric.

Arms, legs, eyes, nostrils, ears, and various ritual implements are all laid out on a systematic grid of angles and intersecting lines.

A skilled thangka artist will generally select from a variety of predesigned items to include in the composition, ranging from alms bowls and animals, to the shape, size, and angle of a figure's eyes, nose, and lips.

The process seems very methodical, but often requires deep understanding of the symbolism involved to capture the spirit of it.

Thangka often overflow with symbolism and allusion.

Because the art is explicitly religious, all symbols and allusions must be in accordance with strict guidelines laid out in Buddhist scripture.

The artist must be properly trained and have sufficient religious understanding, knowledge, and background to create an accurate and appropriate thangka.

Lipton and Ragnubs clarify this in Treasures of Tibetan Art:

“Tibetan art exemplifies the nirmanakaya, the physical body of Buddha, and also the qualities of the Buddha, perhaps in the form of a deity.

Art objects, therefore, must follow rules specified in the Buddhist scriptures regarding proportions, shape, color, stance, hand positions, and attributes in order to personify correctly the Buddha or Deities.”

Gallery

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|