Difference between revisions of "Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Ten: The Relative Severity of Deeds and What Causes It"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| The following selections are from the First Dalai Lama’s commentary to the Treasure House of Knowledge (Abhidharmakosha), entitled Illum...") |

m (Text replacement - "highest form " to "highest form ") |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

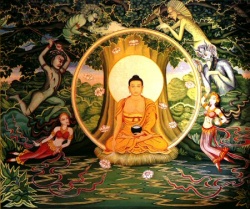

| − | [[File:The-buddha.png|thumb|250px|]] | + | [[File:The-buddha.png|thumb|250px|]]{{DisplayImages|2938|2802|1718|2168|3734|4462|4040|3007}} |

| − | The following selections are from the First Dalai Lama’s commentary to the Treasure House of Knowledge (Abhidharmakosha), entitled Illumination of the Path to Freedom. They include the root text of Master Vasubandhu. | + | The following selections are from the [[First Dalai]] [[Lama’s]] commentary to the [[Treasure]] House of [[Knowledge]] ([[Abhidharmakosha]]), entitled [[Illumination of the Path to Freedom]]. They include the [[root text]] of [[Master]] [[Vasubandhu]]. |

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

116 | 116 | ||

| − | ''The Meritorious Act of Giving | + | ''The [[Meritorious]] Act of Giving |

'''Giving is when anyone acts to give, | '''Giving is when anyone acts to give, | ||

| − | '''Out of a wish to honor or to aid. | + | '''Out of a wish to [[honor]] or to aid. |

| − | '''Deeds of body and speech with motive, linked; | + | '''[[Deeds]] of [[body]] and {{Wiki|speech}} with {{Wiki|motive}}, linked; |

| − | '''Its result, possession of great wealth. | + | '''Its result, possession of great [[wealth]]. |

[IV.449-52] | [IV.449-52] | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| − | Now among these three, giving is described as follows. It is when any person, with thoughts of virtue, acts to give any thing he owns to someone else. As we read in A Sutra Taught at the Request of Vyasa, a Great Adept: “Oh great adept, all acts of giving even the smallest thing from faith are Giving.” As for the motivation involved, it is only the meritorious act of giving when one gives away the thing either out of a wish to honor (some very high object) or out of a wish to aid (some very miserable object). It is not real giving when one does so only out of fear, or out of hopes of getting something in return, and so on. | + | Now among these three, giving is described as follows. It is when any [[person]], with [[thoughts]] of [[virtue]], acts to give any thing he owns to someone else. As we read in A [[Sutra]] [[Taught]] at the Request of Vyasa, a Great {{Wiki|Adept}}: “Oh great {{Wiki|adept}}, all acts of giving even the smallest thing from [[faith]] are Giving.” As for the [[motivation]] involved, it is only the [[meritorious]] act of giving when one gives away the thing either out of a wish to [[honor]] (some very high [[object]]) or out of a wish to aid (some very [[miserable]] [[object]]). It is not real giving when one does so only out of {{Wiki|fear}}, or out of [[Wikipedia:Hope|hopes]] of getting something in return, and so on. |

| − | Giving moreover consists of deeds of body and speech along with their motivation and what is linked with it mentally. The result of the giving is the possession of great wealth, at least for the time being. | + | Giving moreover consists of [[deeds]] of [[body]] and {{Wiki|speech}} along with their [[motivation]] and what is linked with it [[mentally]]. The result of the giving is the possession of great [[wealth]], at least for the time being. |

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

| − | As for the different divisions of giving, the first is that giving which benefits oneself. This would be for a person who had not yet freed himself from desire for desire-realm objects, or for a common person who had done so but through the | + | As for the different divisions of giving, the first is that giving which benefits oneself. This would be for a [[person]] who had not yet freed himself from [[desire]] for desire-realm [[objects]], or for a common [[person]] who had done so but through the “[[path]] of the [[world]],” to make [[offerings]] to a [[shrine]]. |

| − | Giving that benefits the other would be any act of giving performed by a realized person free of desire towards another living being not so freed. This assumes by the way that we do not consider any results that the former individual will experience in this same life. | + | Giving that benefits the other would be any act of giving performed by a [[realized]] [[person]] free of [[desire]] towards another [[living being]] not so freed. This assumes by the way that we do not consider any results that the former {{Wiki|individual}} will [[experience]] in this same [[life]]. |

| − | Giving that benefits both would be for a realized being who was not yet free of desire, or for a common being who was not thus free, to present something to another living being who was not yet free from desire either. | + | Giving that benefits both would be for a [[realized]] being who was not yet free of [[desire]], or for a common being who was not thus free, to {{Wiki|present}} something to another [[living being]] who was not yet free from [[desire]] either. |

| − | Giving that benefits neither would be for a realized being who was free of desire for the desire realm to make offerings to a shrine. This is because the only point of the offering is for this being to express his deep respect and gratitude. Here again incidentally we are not counting any results of the offering that he will achieve in the same life. | + | Giving that benefits neither would be for a [[realized]] being who was free of [[desire]] for the [[desire realm]] to make [[offerings]] to a [[shrine]]. This is because the only point of the [[offering]] is for this being to express his deep [[respect]] and [[gratitude]]. Here again incidentally we are not counting any results of the [[offering]] that he will achieve in the same [[life]]. |

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

118 | 118 | ||

| − | ''Exceptional Types of Givers | + | ''[[Exceptional]] Types of Givers |

| − | '''Exceptional types of it from exceptional | + | '''[[Exceptional]] types of it from [[exceptional]] |

'''Givers, given thing, whom given; of these the | '''Givers, given thing, whom given; of these the | ||

| − | '''Giver’s exceptional through faith and the rest, | + | '''Giver’s [[exceptional]] through [[faith]] and the rest, |

| − | '''Performs his giving with respect and the like. | + | '''Performs his giving with [[respect]] and the like. |

| − | '''As a result one gains the honor, a wealthy, | + | '''As a result one gains the [[honor]], a wealthy, |

| − | '''The timely and a freedom from hindrances. | + | '''The timely and a freedom from [[hindrances]]. |

[IV.455-60] | [IV.455-60] | ||

[[File:Me1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Me1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Very exceptional types of “it”—of this giving, come from exceptional kinds of givers, exceptional kinds of things which are given, and exceptional kinds of objects to whom the things are given. Of these, the giver is made exceptional through a motivation of faith and “the rest”—which refers first of all to the rest of the | + | Very [[exceptional]] types of “it”—of this giving, come from [[exceptional]] kinds of givers, [[exceptional]] kinds of things which are given, and [[exceptional]] kinds of [[objects]] to whom the things are given. Of these, the giver is made [[exceptional]] through a [[motivation]] of [[faith]] and “the rest”—which refers first of all to the rest of the “[[seven riches]] of [[realized beings]]”: [[morality]], [[generosity]], {{Wiki|learning}}, a [[sense of shame]], a {{Wiki|conscience}}, and [[wisdom]]. The [[phrase]] also refers to having little [[desire]] for things. |

| − | As for how he undertakes the act, the exceptional giver performs his giving (1) with an attitude of respect and “the like.” These last words refer to handing the object to the other person with one’s own hands; (2) giving something when it is really needed; and (3) performing the actual deed in a way that does no harm to anyone else. Examples would be where one had stolen the object from someone else in the first place, or where one presented a sheep to a butcher. Included here too are cases where the object given hurt the recipient—examples would be giving someone poison or unhealthy food. Concerning the consequences of such giving, the person has performed his charity with an attitude of respect and so on, as listed above. As a result he gains the following (and here the list follows the three numbers above). In his future life he wins (1) the honor and respect of those who follow him, as well as a wealth of material things (which because of his former faith he enjoys at his total discretion). In this next life he also gains (2) the timely fulfillment of his own needs, as well as (3) complete freedom from any hindrances to his wealth: enemies, loss of his things in a fire, and so on. | + | As for how he undertakes the act, the [[exceptional]] giver performs his giving (1) with an [[attitude]] of [[respect]] and “the like.” These last words refer to handing the [[object]] to the other [[person]] with one’s own hands; (2) giving something when it is really needed; and (3) performing the actual [[deed]] in a way that does no harm to anyone else. Examples would be where one had stolen the [[object]] from someone else in the first place, or where one presented a sheep to a butcher. Included here too are cases where the [[object]] given {{Wiki|hurt}} the recipient—examples would be giving someone [[poison]] or [[unhealthy]] [[food]]. Concerning the {{Wiki|consequences}} of such giving, the [[person]] has performed his [[charity]] with an [[attitude]] of [[respect]] and so on, as listed above. As a result he gains the following (and here the list follows the three numbers above). In his {{Wiki|future}} [[life]] he wins (1) the [[honor]] and [[respect]] of those who follow him, as well as a [[wealth]] of material things (which because of his former [[faith]] he enjoys at his total discretion). In this next [[life]] he also gains (2) the timely fulfillment of his own needs, as well as (3) complete freedom from any [[hindrances]] to his [[wealth]]: enemies, loss of his things in a [[fire]], and so on. |

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

119 | 119 | ||

| − | ''Exceptional Things to Give | + | ''[[Exceptional]] Things to Give |

| − | '''Things given, excellent color and such. | + | '''Things given, {{Wiki|excellent}} {{Wiki|color}} and such. |

| − | '''From it an excellent form and reputation, | + | '''From it an {{Wiki|excellent}} [[form]] and reputation, |

| − | '''Happiness and a very youthful complexion, | + | '''[[Happiness]] and a very youthful complexion, |

| − | '''A body which in each time’s pleasant to touch. | + | '''A [[body]] which in each time’s [[pleasant]] to {{Wiki|touch}}. |

[IV.461-4] | [IV.461-4] | ||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

| − | An excellent color “and such”—which refers to an excellent smell, or taste, or feel—are what make things that are given exceptional. | + | An {{Wiki|excellent}} {{Wiki|color}} “and such”—which refers to an {{Wiki|excellent}} {{Wiki|smell}}, or {{Wiki|taste}}, or feel—are what make things that are given [[exceptional]]. |

| − | From “it” (that is, from giving things with an excellent color), one gains an excellent bodily form—at least for the time being. Temporarily too he gains other results (following the order of the qualities just listed): a good and widespread reputation; great happiness; and a body with a very youthful complexion. The body that one possesses is moreover like that which belongs to the | + | From “it” (that is, from giving things with an {{Wiki|excellent}} {{Wiki|color}}), one gains an {{Wiki|excellent}} [[bodily]] form—at least for the time being. Temporarily too he gains other results (following the order of the qualities just listed): a good and widespread reputation; great [[happiness]]; and a [[body]] with a very youthful complexion. The [[body]] that one possesses is moreover like that which belongs to the “[[jewel]] of the [[Wikipedia:Queen consort|queen]]”: it is [[pleasant]] to {{Wiki|touch}} in each of the times—whether the temperature is just normal, or whether it is cold (when the queen’s [[body]] gives you warmth), or [[hot]] (at which time the [[Wikipedia:Queen consort|queen]] [[feels]] to you cool). |

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

120 | 120 | ||

| − | ''Exceptional Objects to Give a Gift | + | ''[[Exceptional]] [[Objects]] to Give a [[Gift]] |

'''Exceptional—those you give to—by the being, | '''Exceptional—those you give to—by the being, | ||

| − | '''Suffering, aid, and by good qualities. | + | '''[[Suffering]], aid, and by good qualities. |

| − | '''The highest someone freed by someone freed, | + | '''The [[highest]] someone freed by someone freed, |

'''By a bodhisattva, or the eighth. | '''By a bodhisattva, or the eighth. | ||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

'''Gifts made to a father or a mother, | '''Gifts made to a father or a mother, | ||

| − | '''To the sick, a spiritual teacher, or | + | '''To the sick, [[a spiritual teacher]], or |

| − | '''A bodhisattva in his final life | + | '''A bodhisattva in his final [[life]] |

| − | '''Cannot be measured, even not realized. | + | '''Cannot be measured, even not [[realized]]. |

[IV.465-72] | [IV.465-72] | ||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

[[File:LordBuddha 24790.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:LordBuddha 24790.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Those to whom you give a gift can be exceptional by virtue of four different reasons, first by the type of being involved. As Gautami’s Sutra states, | + | Those to whom you give a [[gift]] can be [[exceptional]] by [[virtue]] of four different [[reasons]], first by the type of being involved. As Gautami’s [[Sutra]] states, |

| − | Ananda, you can look forward to a hundredfold result ripening back to you, if you give something to an individual who has reached the animal’s state of birth. But you can look forward to a thousandfold result if you give something even to a human who’s immoral. | + | [[Ananda]], you can look forward to a hundredfold result ripening back to you, if you give something to an {{Wiki|individual}} who has reached the animal’s state of [[birth]]. But you can look forward to a thousandfold result if you give something even to a [[human]] who’s [[immoral]]. |

| − | The object towards whom you perform your giving may also be distinguished by his suffering. Suppose for example that you take all the things that a person can give in one of those types of acts where the merit derives from a substantial thing. It is stated that if you give these things to a sick person, or to someone nursing a sick person, or to someone when it’s cold outside or whatever, the merit is immeasurable. | + | The [[object]] towards whom you perform your giving may also be {{Wiki|distinguished}} by his [[suffering]]. Suppose for example that you take all the things that a [[person]] can give in one of those types of acts where the [[merit]] derives from a substantial thing. It is stated that if you give these things to a sick [[person]], or to someone nursing a sick [[person]], or to someone when it’s cold outside or whatever, the [[merit]] is [[immeasurable]]. |

| − | The recipient may furthermore be distinguished by the aid he has given one in the past. Here we include one’s father and mother, or anyone else who has been of special help to one. Examples may be found among stories of the Buddha’s former lives, such as the one about the bear and the ru-ru deer. The person to whom one gives his gift may, lastly, be exceptional by virtue of his good qualities. Gautami’s Sutra provides some examples: | + | The recipient may furthermore be {{Wiki|distinguished}} by the aid he has given one in the {{Wiki|past}}. Here we include one’s father and mother, or anyone else who has been of special help to one. Examples may be found among stories of the [[Buddha’s]] former [[lives]], such as the one about the bear and the ru-ru {{Wiki|deer}}. The [[person]] to whom one gives his [[gift]] may, lastly, be [[exceptional]] by [[virtue]] of his good qualities. Gautami’s [[Sutra]] provides some examples: |

| − | If you give to someone who has kept his morality, you can expect it to ripen into a result a hundred thousand times as great. If you give to someone who has entered that stage known as the “result of entering the stream,” it ripens into something which is immeasurable. And if you give even more to someone who has entered the stream, the result is even more immeasurable. | + | If you give to someone who has kept his [[morality]], you can expect it to ripen into a result a hundred thousand times as great. If you give to someone who has entered that stage known as the “result of entering the {{Wiki|stream}},” it ripens into something which is [[immeasurable]]. And if you give even more to someone who has entered the {{Wiki|stream}}, the result is even more [[immeasurable]]. |

| − | Now the highest kind of giving is for someone who has freed himself of the three realms to give something to someone else who has freed himself as well. This is because both are the highest kind of individual. Again we see, in Gautami’s Sutra, | + | Now the [[highest]] kind of giving is for someone who has freed himself of the [[three realms]] to give something to someone else who has freed himself as well. This is because both are the [[highest]] kind of {{Wiki|individual}}. Again we see, in Gautami’s [[Sutra]], |

| − | The highest form of giving a physical thing | + | The highest form of giving a [[physical]] thing |

| − | Is by one free to another free of desire: | + | Is by one free to another free of [[desire]]: |

| − | But one with his body and speech restrained, | + | But one with his [[body]] and {{Wiki|speech}} restrained, |

| − | Reaching out his hand to offer food. | + | Reaching out his hand to offer [[food]]. |

| − | We can also though take a giver who is a bodhisattva and who gives any object at all, for the sake of helping every being alive. Although this is an act of giving by a person who is not yet freed and is directed to another person not yet freed, it is still the highest kind of giving. This is because the act has been performed for the sake of total enlightenment and every living being. | + | We can also though take a giver who is a bodhisattva and who gives any [[object]] at all, for the sake of helping every being alive. Although this is an act of giving by a [[person]] who is not yet freed and is directed to another [[person]] not yet freed, it is still the [[highest]] kind of giving. This is because the act has been performed for the sake of total [[enlightenment]] and every [[living being]]. |

And this is because one has given something in order to become the savior of every single being. | And this is because one has given something in order to become the savior of every single being. | ||

| − | Now a certain sutra gives the following list of eight types of giving: | + | Now a certain [[sutra]] gives the following list of eight types of giving: |

1) Giving to close ones; | 1) Giving to close ones; | ||

| − | 2) Giving out of fear; | + | 2) Giving out of {{Wiki|fear}}; |

3) Giving because they gave to you; | 3) Giving because they gave to you; | ||

| Line 154: | Line 154: | ||

4) Giving because they will give to you; | 4) Giving because they will give to you; | ||

| − | 5) Giving because one’s parents and ancestors used to give; | + | 5) Giving because one’s [[parents]] and {{Wiki|ancestors}} used to give; |

| − | 6) Giving with the hope of attaining one of the higher births; | + | 6) Giving with the {{Wiki|hope}} of [[attaining]] one of the higher [[births]]; |

| − | 7) Giving to gain fame; | + | 7) Giving to gain [[fame]]; |

| − | 8) Giving to gain the jewel of the mind, to gain the riches of the mind, to win what great practitioners collect together, to achieve the ultimate goal. | + | 8) Giving to gain the [[jewel]] of the [[mind]], to gain the riches of the [[mind]], to win what great practitioners collect together, to achieve the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] goal. |

| − | We can alternately describe the highest type of giving as the eighth in this list: giving to gain the jewel of the mind and so on. | + | We can alternately describe the [[highest]] type of giving as the eighth in this list: giving to gain the [[jewel]] of the [[mind]] and so on. |

| − | As for the meaning of the expression “giving to close ones,” certain masters of the past have claimed that it refers to giving to someone when they are standing close by, or to someone when they approach close by. “Giving out of | + | As for the meaning of the expression “giving to close ones,” certain [[masters]] of the {{Wiki|past}} have claimed that it refers to giving to someone when they are [[standing]] close by, or to someone when they approach close by. “Giving out of {{Wiki|fear}}” means that a [[person]] decides he will give the best he has, but only because he [[perceives]] some great imminent [[danger]] to himself. And “giving because they gave to you” refers to giving something to a [[person]] with the [[thought]] that “I’m doing this because he gave me something before.” |

| − | The remaining members of the list are easily understood. | + | The remaining members of the list are easily understood. “[[Jewel]] of the [[mind]]” refers to the ability to perform [[miracles]], while “riches of the [[mind]]” refers to the eight parts of the [[path]] of [[realized beings]]. “What great practitioners collect together” refers to perfectly [[tranquil]] [[concentration]] and special [[realization]]. The “[[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] goal” can be described as achieving the state of an enemy destroyer, or the state of [[nirvana]]. This is how the [[Master]] [[Jinaputra]] explains the various types of giving. |

| − | Master Purna explains them as follows: | + | [[Master]] [[Purna]] explains them as follows: |

[[File:Nge.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Nge.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Giving to gain the | + | Giving to gain the “[[jewel]] of the [[mind]]” and the rest of the four refers respectively to (1) that which brings one the riches of [[faith]] and the rest; (2) that which is totally inconsistent with the stink of [[stinginess]]; (3) that which makes the [[happiness]] of balanced [[meditation]] grow; and (4) that which brings on the state of [[nirvana]]. |

| − | These four have also been accepted as relating respectively to the four “results of the way of virtue,” or to (1) the paths of collection and preparation, (2) the path of seeing, (3) the path of habituation, and (4) nirvana. An alternate way is to correlate them with (1) the paths of collection and preparation, (2) the seven impure levels, (3) the three pure levels, and (4) the level of a Buddha. Beyond the above, we can say that there are other acts of giving where, even though the recipient is not a realized being, the resulting merit still cannot be measured in units such as a “hundred thousand times greater” or such. These would involve gifts made to one’s father or mother (recipients who had given one great aid), to the sick (recipients who are in a state of suffering), to a spiritual teacher, or to a bodhisattva in his final life. | + | These four have also been accepted as relating respectively to the four “results of the way of [[virtue]],” or to (1) the [[paths]] of collection and preparation, (2) the [[path of seeing]], (3) the [[path]] of habituation, and (4) [[nirvana]]. An alternate way is to correlate them with (1) the [[paths]] of collection and preparation, (2) the seven impure levels, (3) the three [[pure]] levels, and (4) the level of a Buddha. Beyond the above, we can say that there are other acts of giving where, even though the recipient is not a [[realized]] being, the resulting [[merit]] still cannot be measured in units such as a “hundred thousand times greater” or such. These would involve gifts made to one’s father or mother (recipients who had given one great aid), to the sick (recipients who are in a state of [[suffering]]), to [[a spiritual teacher]], or to a bodhisattva in his final [[life]]. |

| − | Support for this description can be found in the Sutra on Causes and Effect of Right and Wrong, which equates the merit of giving to these objects with the amount of merit you collect from giving something to the Buddha himself: | + | Support for this description can be found in the [[Sutra]] on [[Causes]] and Effect of Right and Wrong, which equates the [[merit]] of giving to these [[objects]] with the amount of [[merit]] you collect from giving something to the Buddha himself: |

| − | Moreover, the act of giving performed towards any one of the three different kinds of individuals ripens into a result which never reaches an end at all. These objects are the One Thus Gone, a person’s parents, and the sick. | + | Moreover, the act of giving performed towards any one of the three different kinds of {{Wiki|individuals}} ripens into a result which never reaches an end at all. These [[objects]] are the One [[Thus Gone]], a person’s [[parents]], and the sick. |

121 | 121 | ||

| − | ''Severity of Deeds according to Six Factors | + | ''Severity of [[Deeds]] according to Six Factors |

'''Conclusion, one who’s acted toward, commission; | '''Conclusion, one who’s acted toward, commission; | ||

| − | '''Undertaking, thinking, and intention: | + | '''{{Wiki|Undertaking}}, [[thinking]], and [[intention]]: |

| − | '''The power of the deed itself’s exactly | + | '''The power of the [[deed]] itself’s exactly |

'''As little or great as these happen to be. | '''As little or great as these happen to be. | ||

| Line 194: | Line 194: | ||

| − | Here we might touch by the way on what determines how serious a given deed will be. The first factor that can make a deed serious is what we call “performance in conclusion,” which means to continue a particular act well after the original course of action. | + | Here we might {{Wiki|touch}} by the way on what determines how serious a given [[deed]] will be. The first factor that can make a [[deed]] serious is what we call “performance in conclusion,” which means to continue a particular act well after the original course of [[action]]. |

| − | The one who’s acted toward in any particular deed—someone who may have lent one great aid in the past—is also a factor in making the deed a serious one. Deeds which are more serious because of the basic type involved in the actual commission of the act would include cases like killing (among the different deeds of the body), lying (among the deeds of speech), and mistaken views (among the deeds of thought). Even among the different types of killing there are those which are more serious—killing an enemy destroyer, for example—because as Close Recollection states, | + | The one who’s acted toward in any particular deed—someone who may have lent one great aid in the past—is also a factor in making the [[deed]] a serious one. [[Deeds]] which are more serious because of the basic type involved in the actual commission of the act would include cases like {{Wiki|killing}} (among the different [[deeds]] of the [[body]]), {{Wiki|lying}} (among the [[deeds]] of {{Wiki|speech}}), and mistaken [[views]] (among the [[deeds]] of [[thought]]). Even among the different types of {{Wiki|killing}} there are those which are more serious—killing an enemy destroyer, for example—because as Close [[Recollection]] states, |

| − | …it leads one to the lowest hell, “Without Respite.” A less serious type of killing would be to take the life of a person who had reached any of the paths. And the least serious type would be to kill an animal, or a very immoral person. | + | …it leads one to the lowest [[hell]], “Without Respite.” A less serious type of {{Wiki|killing}} would be to take the [[life]] of a [[person]] who had reached any of the [[paths]]. And the least serious type would be to kill an [[animal]], or a very [[immoral]] [[person]]. |

| − | Deeds made serious by the stage of their preliminary undertaking would be those which involved actually applying oneself physically or verbally. Deeds made serious by the thinking involved would be those where one’s thoughts in carrying out the act were particularly strong. And deeds which turn more serious because of the intention involved would be those where one undertakes an act with particularly strong thoughts of motivation. | + | [[Deeds]] made serious by the stage of their preliminary {{Wiki|undertaking}} would be those which involved actually applying oneself {{Wiki|physically}} or verbally. [[Deeds]] made serious by the [[thinking]] involved would be those where one’s [[thoughts]] in carrying out the act were particularly strong. And [[deeds]] which turn more serious because of the [[intention]] involved would be those where one undertakes an act with particularly strong [[thoughts]] of [[motivation]]. |

| − | We can summarize by saying that the power of the deed itself is exactly as little or great as these six factors of conclusion and the rest happen to be in their own force. One should understand that deeds where all six factors are present in force are extremely serious. | + | We can summarize by saying that the power of the [[deed]] itself is exactly as little or great as these six factors of conclusion and the rest happen to be in their own force. One should understand that [[deeds]] where all six factors are {{Wiki|present}} in force are extremely serious. |

| Line 208: | Line 208: | ||

122 | 122 | ||

[[File:Ma-buddha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Ma-buddha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | ''Whether Deeds are Collected or Not | + | ''Whether [[Deeds]] are Collected or Not |

| − | '''A deed is called “collected” from its being | + | '''A [[deed]] is called “collected” from its being |

'''Done intentionally, to its completion, | '''Done intentionally, to its completion, | ||

| − | '''Without regret, without a counteraction, | + | '''Without [[regret]], without a counteraction, |

'''With attendants, ripening as well. | '''With attendants, ripening as well. | ||

| Line 222: | Line 222: | ||

| − | Now sutra also mentions a number of concepts including | + | Now [[sutra]] also mentions a number of [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] including “[[deeds]] which are done and also collected” as well as “[[deeds]] which are done but which are not collected.” One may ask just what these are. |

| − | A deed is called “done and also collected” from its being done with six different conditions, described as follows: | + | A [[deed]] is called “done and also collected” from its being done with six different [[conditions]], described as follows: |

| − | 1) The deed must be done intentionally; that is, it cannot have been performed without premeditation, or simply on the spur of the moment. | + | 1) The [[deed]] must be done intentionally; that is, it cannot have been performed without premeditation, or simply on the spur of the moment. |

| − | 2) I t must have been done “to its completion”—meaning with all the various elements of a complete deed present. | + | 2) I t must have been done “to its completion”—meaning with all the various [[elements]] of a complete [[deed]] {{Wiki|present}}. |

| − | 3) The person who committed the deed must feel no regret later on. | + | 3) The [[person]] who committed the [[deed]] must [[feel]] no [[regret]] later on. |

| − | 4) There must be no counteraction to work against the force of the deed. | + | 4) There must be no counteraction to work against the force of the [[deed]]. |

| − | 5) The deed must come along with the necessary attendants. | + | 5) The [[deed]] must come along with the necessary attendants. |

| − | 6) The deed must as well be one of those where one is certain to experience the ripening of a result in the future. | + | 6) The [[deed]] must as well be one of those where one is certain to [[experience]] the ripening of a result in the {{Wiki|future}}. |

| − | Deeds other than the type described are what we call “done but not collected.” From this one can understand what kinds of deeds are meant by the expressions “collected but not done” and “neither done nor collected.” As for the phrase “to its completion,” in some cases a single act of right or wrong leads one to a birth in the states of misery or to a birth in the happier states. In other cases, all ten deeds of all three doors lead a person to the appropriate one of these two births. In either case the deeds have been done to their completion. | + | [[Deeds]] other than the type described are what we call “done but not collected.” From this one can understand what kinds of [[deeds]] are meant by the {{Wiki|expressions}} “collected but not done” and “neither done nor collected.” As for the [[phrase]] “to its completion,” in some cases a single act of right or wrong leads one to a [[birth]] in the states of [[misery]] or to a [[birth]] in the [[happier]] states. In other cases, all ten [[deeds]] of all [[three doors]] lead a [[person]] to the appropriate one of these two [[births]]. In either case the [[deeds]] have been done to their completion. |

| − | The phrase “without a counteraction” refers to deeds done (1) with mistaken ideas, misgivings, or the like; (2) without confession, future restraint, or such. A deed “along with its necessary attendants” means a deed of virtue or nonvirtue along with attendants of further virtue or non-virtue. Admittedly, the Commentary does explains these as “Any deed which you rejoice about having done.” Nonetheless the attendants here are the preliminary undertaking and final conclusion stages of the deed. | + | The [[phrase]] “without a counteraction” refers to [[deeds]] done (1) with mistaken [[ideas]], misgivings, or the like; (2) without {{Wiki|confession}}, {{Wiki|future}} {{Wiki|restraint}}, or such. A [[deed]] “along with its necessary attendants” means a [[deed]] of [[virtue]] or [[nonvirtue]] along with attendants of further [[virtue]] or [[non-virtue]]. Admittedly, the Commentary does explains these as “Any [[deed]] which you rejoice about having done.” Nonetheless the attendants here are the preliminary {{Wiki|undertaking}} and final conclusion stages of the [[deed]]. |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Latest revision as of 09:21, 29 January 2016

The following selections are from the First Dalai Lama’s commentary to the Treasure House of Knowledge (Abhidharmakosha), entitled Illumination of the Path to Freedom. They include the root text of Master Vasubandhu.

116

The Meritorious Act of Giving

Giving is when anyone acts to give,

Out of a wish to honor or to aid.

Deeds of body and speech with motive, linked;

Its result, possession of great wealth.

[IV.449-52]

Now among these three, giving is described as follows. It is when any person, with thoughts of virtue, acts to give any thing he owns to someone else. As we read in A Sutra Taught at the Request of Vyasa, a Great Adept: “Oh great adept, all acts of giving even the smallest thing from faith are Giving.” As for the motivation involved, it is only the meritorious act of giving when one gives away the thing either out of a wish to honor (some very high object) or out of a wish to aid (some very miserable object). It is not real giving when one does so only out of fear, or out of hopes of getting something in return, and so on.

Giving moreover consists of deeds of body and speech along with their motivation and what is linked with it mentally. The result of the giving is the possession of great wealth, at least for the time being.

117

Giving that Benefits the Other,

and the Rest

Giving is that which benefits oneself,

The other, both, and neither one of them.

[IV.453-4]

As for the different divisions of giving, the first is that giving which benefits oneself. This would be for a person who had not yet freed himself from desire for desire-realm objects, or for a common person who had done so but through the “path of the world,” to make offerings to a shrine.

Giving that benefits the other would be any act of giving performed by a realized person free of desire towards another living being not so freed. This assumes by the way that we do not consider any results that the former individual will experience in this same life.

Giving that benefits both would be for a realized being who was not yet free of desire, or for a common being who was not thus free, to present something to another living being who was not yet free from desire either.

Giving that benefits neither would be for a realized being who was free of desire for the desire realm to make offerings to a shrine. This is because the only point of the offering is for this being to express his deep respect and gratitude. Here again incidentally we are not counting any results of the offering that he will achieve in the same life.

118

Exceptional Types of Givers

Exceptional types of it from exceptional

Givers, given thing, whom given; of these the

Giver’s exceptional through faith and the rest,

Performs his giving with respect and the like.

As a result one gains the honor, a wealthy,

The timely and a freedom from hindrances.

[IV.455-60]

Very exceptional types of “it”—of this giving, come from exceptional kinds of givers, exceptional kinds of things which are given, and exceptional kinds of objects to whom the things are given. Of these, the giver is made exceptional through a motivation of faith and “the rest”—which refers first of all to the rest of the “seven riches of realized beings”: morality, generosity, learning, a sense of shame, a conscience, and wisdom. The phrase also refers to having little desire for things.

As for how he undertakes the act, the exceptional giver performs his giving (1) with an attitude of respect and “the like.” These last words refer to handing the object to the other person with one’s own hands; (2) giving something when it is really needed; and (3) performing the actual deed in a way that does no harm to anyone else. Examples would be where one had stolen the object from someone else in the first place, or where one presented a sheep to a butcher. Included here too are cases where the object given hurt the recipient—examples would be giving someone poison or unhealthy food. Concerning the consequences of such giving, the person has performed his charity with an attitude of respect and so on, as listed above. As a result he gains the following (and here the list follows the three numbers above). In his future life he wins (1) the honor and respect of those who follow him, as well as a wealth of material things (which because of his former faith he enjoys at his total discretion). In this next life he also gains (2) the timely fulfillment of his own needs, as well as (3) complete freedom from any hindrances to his wealth: enemies, loss of his things in a fire, and so on.

119

Exceptional Things to Give

Things given, excellent color and such.

From it an excellent form and reputation,

Happiness and a very youthful complexion,

A body which in each time’s pleasant to touch.

[IV.461-4]

An excellent color “and such”—which refers to an excellent smell, or taste, or feel—are what make things that are given exceptional.

From “it” (that is, from giving things with an excellent color), one gains an excellent bodily form—at least for the time being. Temporarily too he gains other results (following the order of the qualities just listed): a good and widespread reputation; great happiness; and a body with a very youthful complexion. The body that one possesses is moreover like that which belongs to the “jewel of the queen”: it is pleasant to touch in each of the times—whether the temperature is just normal, or whether it is cold (when the queen’s body gives you warmth), or hot (at which time the queen feels to you cool).

120

Exceptional Objects to Give a Gift

Exceptional—those you give to—by the being,

Suffering, aid, and by good qualities.

The highest someone freed by someone freed,

By a bodhisattva, or the eighth.

Gifts made to a father or a mother,

To the sick, a spiritual teacher, or

A bodhisattva in his final life

Cannot be measured, even not realized.

[IV.465-72]

Those to whom you give a gift can be exceptional by virtue of four different reasons, first by the type of being involved. As Gautami’s Sutra states,

Ananda, you can look forward to a hundredfold result ripening back to you, if you give something to an individual who has reached the animal’s state of birth. But you can look forward to a thousandfold result if you give something even to a human who’s immoral.

The object towards whom you perform your giving may also be distinguished by his suffering. Suppose for example that you take all the things that a person can give in one of those types of acts where the merit derives from a substantial thing. It is stated that if you give these things to a sick person, or to someone nursing a sick person, or to someone when it’s cold outside or whatever, the merit is immeasurable.

The recipient may furthermore be distinguished by the aid he has given one in the past. Here we include one’s father and mother, or anyone else who has been of special help to one. Examples may be found among stories of the Buddha’s former lives, such as the one about the bear and the ru-ru deer. The person to whom one gives his gift may, lastly, be exceptional by virtue of his good qualities. Gautami’s Sutra provides some examples:

If you give to someone who has kept his morality, you can expect it to ripen into a result a hundred thousand times as great. If you give to someone who has entered that stage known as the “result of entering the stream,” it ripens into something which is immeasurable. And if you give even more to someone who has entered the stream, the result is even more immeasurable.

Now the highest kind of giving is for someone who has freed himself of the three realms to give something to someone else who has freed himself as well. This is because both are the highest kind of individual. Again we see, in Gautami’s Sutra,

The highest form of giving a physical thing

Is by one free to another free of desire:

But one with his body and speech restrained,

Reaching out his hand to offer food.

We can also though take a giver who is a bodhisattva and who gives any object at all, for the sake of helping every being alive. Although this is an act of giving by a person who is not yet freed and is directed to another person not yet freed, it is still the highest kind of giving. This is because the act has been performed for the sake of total enlightenment and every living being.

And this is because one has given something in order to become the savior of every single being.

Now a certain sutra gives the following list of eight types of giving:

1) Giving to close ones;

2) Giving out of fear;

3) Giving because they gave to you;

4) Giving because they will give to you;

5) Giving because one’s parents and ancestors used to give;

6) Giving with the hope of attaining one of the higher births;

7) Giving to gain fame;

8) Giving to gain the jewel of the mind, to gain the riches of the mind, to win what great practitioners collect together, to achieve the ultimate goal.

We can alternately describe the highest type of giving as the eighth in this list: giving to gain the jewel of the mind and so on.

As for the meaning of the expression “giving to close ones,” certain masters of the past have claimed that it refers to giving to someone when they are standing close by, or to someone when they approach close by. “Giving out of fear” means that a person decides he will give the best he has, but only because he perceives some great imminent danger to himself. And “giving because they gave to you” refers to giving something to a person with the thought that “I’m doing this because he gave me something before.”

The remaining members of the list are easily understood. “Jewel of the mind” refers to the ability to perform miracles, while “riches of the mind” refers to the eight parts of the path of realized beings. “What great practitioners collect together” refers to perfectly tranquil concentration and special realization. The “ultimate goal” can be described as achieving the state of an enemy destroyer, or the state of nirvana. This is how the Master Jinaputra explains the various types of giving.

Master Purna explains them as follows:

Giving to gain the “jewel of the mind” and the rest of the four refers respectively to (1) that which brings one the riches of faith and the rest; (2) that which is totally inconsistent with the stink of stinginess; (3) that which makes the happiness of balanced meditation grow; and (4) that which brings on the state of nirvana.

These four have also been accepted as relating respectively to the four “results of the way of virtue,” or to (1) the paths of collection and preparation, (2) the path of seeing, (3) the path of habituation, and (4) nirvana. An alternate way is to correlate them with (1) the paths of collection and preparation, (2) the seven impure levels, (3) the three pure levels, and (4) the level of a Buddha. Beyond the above, we can say that there are other acts of giving where, even though the recipient is not a realized being, the resulting merit still cannot be measured in units such as a “hundred thousand times greater” or such. These would involve gifts made to one’s father or mother (recipients who had given one great aid), to the sick (recipients who are in a state of suffering), to a spiritual teacher, or to a bodhisattva in his final life.

Support for this description can be found in the Sutra on Causes and Effect of Right and Wrong, which equates the merit of giving to these objects with the amount of merit you collect from giving something to the Buddha himself:

Moreover, the act of giving performed towards any one of the three different kinds of individuals ripens into a result which never reaches an end at all. These objects are the One Thus Gone, a person’s parents, and the sick.

121

Severity of Deeds according to Six Factors

Conclusion, one who’s acted toward, commission;

Undertaking, thinking, and intention:

The power of the deed itself’s exactly

As little or great as these happen to be.

[IV.473-6]

Here we might touch by the way on what determines how serious a given deed will be. The first factor that can make a deed serious is what we call “performance in conclusion,” which means to continue a particular act well after the original course of action.

The one who’s acted toward in any particular deed—someone who may have lent one great aid in the past—is also a factor in making the deed a serious one. Deeds which are more serious because of the basic type involved in the actual commission of the act would include cases like killing (among the different deeds of the body), lying (among the deeds of speech), and mistaken views (among the deeds of thought). Even among the different types of killing there are those which are more serious—killing an enemy destroyer, for example—because as Close Recollection states,

…it leads one to the lowest hell, “Without Respite.” A less serious type of killing would be to take the life of a person who had reached any of the paths. And the least serious type would be to kill an animal, or a very immoral person.

Deeds made serious by the stage of their preliminary undertaking would be those which involved actually applying oneself physically or verbally. Deeds made serious by the thinking involved would be those where one’s thoughts in carrying out the act were particularly strong. And deeds which turn more serious because of the intention involved would be those where one undertakes an act with particularly strong thoughts of motivation.

We can summarize by saying that the power of the deed itself is exactly as little or great as these six factors of conclusion and the rest happen to be in their own force. One should understand that deeds where all six factors are present in force are extremely serious.

122

Whether Deeds are Collected or Not

A deed is called “collected” from its being

Done intentionally, to its completion,

Without regret, without a counteraction,

With attendants, ripening as well.

[IV.477-80]

Now sutra also mentions a number of concepts including “deeds which are done and also collected” as well as “deeds which are done but which are not collected.” One may ask just what these are.

A deed is called “done and also collected” from its being done with six different conditions, described as follows:

1) The deed must be done intentionally; that is, it cannot have been performed without premeditation, or simply on the spur of the moment.

2) I t must have been done “to its completion”—meaning with all the various elements of a complete deed present.

3) The person who committed the deed must feel no regret later on.

4) There must be no counteraction to work against the force of the deed.

5) The deed must come along with the necessary attendants.

6) The deed must as well be one of those where one is certain to experience the ripening of a result in the future.

Deeds other than the type described are what we call “done but not collected.” From this one can understand what kinds of deeds are meant by the expressions “collected but not done” and “neither done nor collected.” As for the phrase “to its completion,” in some cases a single act of right or wrong leads one to a birth in the states of misery or to a birth in the happier states. In other cases, all ten deeds of all three doors lead a person to the appropriate one of these two births. In either case the deeds have been done to their completion.

The phrase “without a counteraction” refers to deeds done (1) with mistaken ideas, misgivings, or the like; (2) without confession, future restraint, or such. A deed “along with its necessary attendants” means a deed of virtue or nonvirtue along with attendants of further virtue or non-virtue. Admittedly, the Commentary does explains these as “Any deed which you rejoice about having done.” Nonetheless the attendants here are the preliminary undertaking and final conclusion stages of the deed.

See also

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading One: Introduction to Abhidharma

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Two: The Nature of Karma, and What it Produces; the Detailist Concept of ''Non-Communicating Form''

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Three: Types of Deeds, and the Nature of Motivation

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Four: The Correlation of Deeds and Their Results

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Five: How Karma is Carried, According to the Mind- Only School

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Six: How Emptiness Allows Karma to Work, According to the Middle-Way School

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Seven: Black and White Deeds, the “Path of Action,” and the Root and Branch Non-Virtues

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Eight: Most Basic Virtue, and the Projecting and Finishing Energy of Deeds

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Nine: The Five Immediate Misdeeds, and the Concept of a Schism

- Manual of Abhidharma - Reading Ten: The Relative Severity of Deeds and What Causes It

- Manual of Abhidharma - Additions Part 1

- Manual of Abhidharma - Additions Part 2