Difference between revisions of "Manual of Pramana - Reading Ten: The Concept of Time"

(Created page with "Selection from the collected topics: thumb|250px| The Concept of Time The following selections on the concept of time (Dus-gsum gyi rnam-bz...") |

m (Text replacement - "]]]" to "]])") |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | Selection from the collected topics: | + | Selection from the [[collected topics]]: |

| − | [[File:Buddhas.life.b.016.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | + | [[File:Buddhas.life.b.016.jpg|thumb|250px|]]{{DisplayImages|1406|1847|335|1949|4466|2746|3414|325|2038|2253|1343|3693|1607|2477|1549|3471|3775|2671|3196|3207|1017|2416|577|2122|2230|4031|2677|235|28|2633|4179|2008|2983|4484|3724|1809|1065|2767|1541|464|883|2431|870|1462|1741|3721|3419|581|3231|3815|986|2840|907|2631|496}} |

| − | The Concept of Time | + | The [[Concept of Time]] |

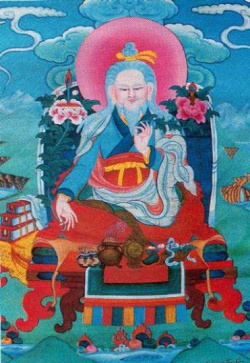

| − | The following selections on the concept of time (Dus-gsum gyi rnam-bzhag), are excerpted from The Collected Topics of Rato (Rva-stod bsdus-grva), by Master Chokhla U-ser, a great master of Rato Monastery who lived about 1500 AD. This particular book is considered the “grandfather” of what came to be a separate genre of literature in Tibet: the dura (bsdus-grva), or “selected topics from the Commentary on Valid Perception (Pramana Varttika, or Tsad-ma rnam-’grel) of Master Dharmakirti (circa 650 AD). | + | The following selections on the [[concept of time]] ([[Dus-gsum gyi rnam-bzhag]]), are excerpted from The [[Collected Topics]] of Rato ([[Rva-stod bsdus-grva]]), by [[Master]] [[Chokhla U-ser]], a [[great master]] of [[Rato Monastery]] who lived about 1500 AD. This particular [[book]] is considered the “grandfather” of what came to be a separate genre of {{Wiki|literature}} in [[Tibet]]: the [[dura]] ([[bsdus-grva]]), or “selected topics from the [[Commentary on Valid Perception]] ([[Pramana Varttika]], or [[Tsad-ma rnam-’grel]]) of [[Master]] [[Dharmakirti]] (circa 650 AD). |

| − | Please note that indented statements are usually those given by the opponent. Responses within brackets are those that are usually left unwritten in the Tibetan text, and are understood to be there because of the context following each. | + | Please note that indented statements are usually those given by the opponent. Responses within brackets are those that are usually left unwritten in the [[Tibetan]] text, and are understood to be there because of the context following each. |

_______________ | _______________ | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

Suppose someone comes again, and makes the following claim: | Suppose someone comes again, and makes the following claim: | ||

| − | The definition of the past is: “That which has begun and stopped.” The definition of the present is: “That which has begun and not yet stopped.” The definition of the future is: “That condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are present.” | + | The [[definition]] of the {{Wiki|past}} is: “That which has begun and stopped.” The [[definition]] of the {{Wiki|present}} is: “That which has begun and not yet stopped.” The [[definition]] of the {{Wiki|future}} is: “That [[condition]] of having not yet begun, although the [[causes]] for beginning are {{Wiki|present}}.” |

Respective examples would be the following. For the first, the example would be last year’s crops. For the second, it would be this year’s crops; and, for the third, crops soon to grow. | Respective examples would be the following. For the first, the example would be last year’s crops. For the second, it would be this year’s crops; and, for the third, crops soon to grow. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Concerning the first of these, we answer as follows. | Concerning the first of these, we answer as follows. | ||

| − | Aren’t your definition and example for the past though incorrect? | + | Aren’t your [[definition]] and example for the {{Wiki|past}} though incorrect? |

| − | Because there is no definition for the past, | + | Because there is no [[definition]] for the {{Wiki|past}}, |

| − | And this is because the past doesn’t even exist, | + | And this is because the {{Wiki|past}} doesn’t even [[exist]], |

| − | And this is because anything which can be established as existing is always something of the present. | + | And this is because anything which can be established as [[existing]] is always something of the {{Wiki|present}}. |

On this point, someone may come and make the following claim: | On this point, someone may come and make the following claim: | ||

| − | But there must be things that are past, | + | But there must be things that are {{Wiki|past}}, |

| − | Because past time exists; | + | Because {{Wiki|past}} [[time]] [[exists]]; |

| − | And this is because all three—past time, and future time, and present time—exist. | + | And this is because all three—past [[time]], and {{Wiki|future}} [[time]], and {{Wiki|present}} time—exist. |

| − | And this is because the three times exist. | + | And this is because the three times [[exist]]. |

To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | ||

| − | And we also ask this person, | + | And we also ask this [[person]], |

| − | So is the past the past? | + | So is the {{Wiki|past}} the {{Wiki|past}}? |

| − | Because the past exists. | + | Because the {{Wiki|past}} [[exists]]. |

| − | You already agreed to the reason here. | + | You already agreed to the [[reason]] here. |

| − | [Then I agree to your original statement: the past is the past.] | + | [Then I agree to your original statement: the {{Wiki|past}} is the {{Wiki|past}}.] |

Suppose you agree to our original statement. | Suppose you agree to our original statement. | ||

| − | Consider the past. | + | Consider the {{Wiki|past}}. |

| − | It is not so the past, | + | It is not so the {{Wiki|past}}, |

Because it is not something which has stopped; | Because it is not something which has stopped; | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

But it does necessarily follow, | But it does necessarily follow, | ||

| − | Because “the past,” “that which has stopped,” and “that which has been destroyed” all refer to the same thing. | + | Because “the {{Wiki|past}},” “that which has stopped,” and “that which has been destroyed” all refer to the same thing. |

| − | And this is true because all three of them exist; | + | And this is true because all three of them [[exist]]; |

| − | And this is true because the past exists. | + | And this is true because the {{Wiki|past}} [[exists]]. |

| − | You already agreed that the reason is true. | + | You already agreed that the [[reason]] is true. |

Suppose that, instead of “it doesn’t necessarily follow,” the opponent says “it’s incorrect.” | Suppose that, instead of “it doesn’t necessarily follow,” the opponent says “it’s incorrect.” | ||

| − | Consider the past. | + | Consider the {{Wiki|past}}. |

It is not so something which has been destroyed, | It is not so something which has been destroyed, | ||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

But it does necessarily follow, | But it does necessarily follow, | ||

| − | Because there exists no one thing which is both (1) something that has been destroyed but which is still (2) a working thing. | + | Because there [[exists]] no one thing which is both (1) something that has been destroyed but which is still (2) a working thing. |

And this is true because the Golden Necklace of Good Explanation says, | And this is true because the Golden Necklace of Good Explanation says, | ||

| − | None of the schools that belong to the side that believe that things exist through some nature of their own accept the idea that something which has been destroyed could be a working thing. | + | None of the schools that belong to the side that believe that things [[exist]] through some [[nature]] of their [[own]] accept the [[idea]] that something which has been destroyed could be a working thing. |

| − | [The Golden Necklace is a famed commentary by Je Tsongkapa upon the Ornament of Realizations, spoken to the realized being Asanga by Lord Maitreya.] | + | [The Golden Necklace is a famed commentary by [[Je Tsongkapa]] upon the Ornament of Realizations, spoken to the [[realized]] being [[Asanga]] by [[Lord Maitreya]].] |

[Then I disagree to your earlier statement.] | [Then I disagree to your earlier statement.] | ||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

Suppose you say that the earlier one is not correct. | Suppose you say that the earlier one is not correct. | ||

| − | Consider the past. | + | Consider the {{Wiki|past}}. |

It is so a working thing, | It is so a working thing, | ||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

Because it is something made. | Because it is something made. | ||

| − | [It's not correct to say that the past is something made.] | + | [It's not correct to say that the {{Wiki|past}} is something made.] |

Suppose you say that it’s not correct. | Suppose you say that it’s not correct. | ||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

But it does necessarily follow, | But it does necessarily follow, | ||

| − | Because “something that started” is the definition of “something made.” | + | Because “something that started” is the [[definition]] of “something made.” |

[The earlier point is not correct.] | [The earlier point is not correct.] | ||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

Suppose you say that the earlier point is not correct. | Suppose you say that the earlier point is not correct. | ||

| − | Consider the past. | + | Consider the {{Wiki|past}}. |

It is so something that started, | It is so something that started, | ||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

Because it is something that started and then stopped. | Because it is something that started and then stopped. | ||

| − | And this is true because it’s the past. | + | And this is true because it’s the {{Wiki|past}}. |

| − | You’ve agreed both to the reason and to what we’re asserting must be so, and the necessity is something that does apply to the definition. It must moreover be true that that which has been destroyed is a working thing, | + | You’ve agreed both to the [[reason]] and to what we’re asserting must be so, and the necessity is something that does apply to the [[definition]]. It must moreover be true that that which has been destroyed is a working thing, |

| − | Because the past is a working thing. | + | Because the {{Wiki|past}} is a working thing. |

| − | We’ve already established that the reason is true. | + | We’ve already established that the [[reason]] is true. |

Suppose you do agree. | Suppose you do agree. | ||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

Is it then the case that a working thing which has been destroyed is still a working thing? | Is it then the case that a working thing which has been destroyed is still a working thing? | ||

| − | Because (1) there does exist a working thing which has been destroyed, and (2) that which has been destroyed is a working thing. | + | Because (1) there does [[exist]] a working thing which has been destroyed, and (2) that which has been destroyed is a working thing. |

| − | You’ve already agreed to the latter part of the reason. | + | You’ve already agreed to the [[latter]] part of the [[reason]]. |

Suppose now you say that the first part is not correct. | Suppose now you say that the first part is not correct. | ||

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

The first is too correct, | The first is too correct, | ||

| − | Because there does exist a working thing which is past. | + | Because there does [[exist]] a working thing which is {{Wiki|past}}. |

| − | [It's not correct to say that there does exist a working thing which is past.] | + | [It's not correct to say that there does [[exist]] a working thing which is {{Wiki|past}}.] |

Suppose you say that it’s not correct. | Suppose you say that it’s not correct. | ||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

Consider a working thing. | Consider a working thing. | ||

| − | There does too exist it past, | + | There does too [[exist]] it {{Wiki|past}}, |

Because it is something that has been produced. | Because it is something that has been produced. | ||

| Line 163: | Line 163: | ||

Suppose you agree to our second original statement. | Suppose you agree to our second original statement. | ||

| − | So is a tree that was already destroyed still a tree? | + | So is a [[tree]] that was already destroyed still a [[tree]]? |

Because a working thing which has been destroyed is still a working thing. | Because a working thing which has been destroyed is still a working thing. | ||

| − | You’ve already accepted the reason. | + | You’ve already accepted the [[reason]]. |

| − | [Then I agree to your original statement: a tree that was already destroyed is still a tree.] | + | [Then I agree to your original statement: a [[tree]] that was already destroyed is still a [[tree]].] |

Suppose you agree to our original statement. | Suppose you agree to our original statement. | ||

| − | So is it then true that when a tree has been burned up by fire there is still a tree? | + | So is it then true that when a [[tree]] has been burned up by [[fire]] there is still a [[tree]]? |

| − | Because (1) a tree that was already destroyed is a tree; and (2) there exists a destroyed tree subsequent to the burning up of a tree by a fire. | + | Because (1) a [[tree]] that was already destroyed is a [[tree]]; and (2) there [[exists]] a destroyed [[tree]] subsequent to the burning up of a [[tree]] by a [[fire]]. |

| − | And this is so because—when a tree has been burned up by fire—there is a tree destroyed. | + | And this is so because—when a [[tree]] has been burned up by fire—there is a [[tree]] destroyed. |

[I agree to your statement above.] | [I agree to your statement above.] | ||

| Line 183: | Line 183: | ||

Suppose you agree to our statement above. | Suppose you agree to our statement above. | ||

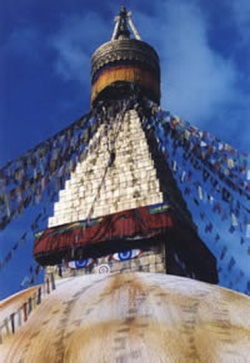

[[File:Imag36es.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Imag36es.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Is it then the case that—subsequent to the burning up of a tree by a fire—you can still see a tree by using your visual consciousness? | + | Is it then the case that—subsequent to the burning up of a [[tree]] by a fire—you can still see a [[tree]] by using your [[visual consciousness]]? |

| − | Because there does exist a tree subsequent to that point. | + | Because there does [[exist]] a [[tree]] subsequent to that point. |

| − | You already agreed to the reason. | + | You already agreed to the [[reason]]. |

| − | If the one is the case, then the other is necessarily so. [That is, if there does exist a tree subsequent to that point, then you must be able to see it by using your visual consciousness.] | + | If the one is the case, then the other is necessarily so. [That is, if there does [[exist]] a [[tree]] subsequent to that point, then you must be able to see it by using your [[visual consciousness]].] |

And you cannot agree to this last statement; | And you cannot agree to this last statement; | ||

| − | Because the following quotation from the Commentary on Valid Perception was meant to point out—to those who asserted that something which was destroyed could ever be a working thing—what very absurd consequences their position entailed: | + | Because the following quotation from the Commentary on Valid [[Perception]] was meant to point out—to those who asserted that something which was destroyed could ever be a working thing—what very absurd {{Wiki|consequences}} their position entailed: |

Because it has started, then the destruction | Because it has started, then the destruction | ||

| − | Must be destroyed; and then the tree | + | Must be destroyed; and then the [[tree]] |

Would have to be seen once more. | Would have to be seen once more. | ||

| − | Concerning the second of the original definitions, [that the definition of the present is "that which has begun and not yet stopped,"] we pose the following: | + | Concerning the second of the original definitions, [that the [[definition]] of the {{Wiki|present}} is "that which has begun and not yet stopped,"] we pose the following: |

Consider “knowable things.” | Consider “knowable things.” | ||

| Line 207: | Line 207: | ||

So is it something which has begun and not yet stopped? | So is it something which has begun and not yet stopped? | ||

| − | Because it is something of the present. | + | Because it is something of the {{Wiki|present}}. |

[It doesn't necessarily follow.] | [It doesn't necessarily follow.] | ||

| Line 213: | Line 213: | ||

But you already agree that it does necessarily follow. | But you already agree that it does necessarily follow. | ||

| − | [It's not correct to say that "knowable things" is something of the present.] | + | [It's not correct to say that "knowable things" is something of the {{Wiki|present}}.] |

It is so correct, | It is so correct, | ||

| − | Because it can be established as existing. | + | Because it can be established as [[existing]]. |

[Then I agree to your statement above: "knowable things" is something that has begun and not yet stopped.] | [Then I agree to your statement above: "knowable things" is something that has begun and not yet stopped.] | ||

| Line 229: | Line 229: | ||

Because it has begun and not yet stopped. | Because it has begun and not yet stopped. | ||

| − | You already agreed to the reason. | + | You already agreed to the [[reason]]. |

[Then I agree to your statement.] | [Then I agree to your statement.] | ||

| Line 239: | Line 239: | ||

It is not so, that it is something which ever began, | It is not so, that it is something which ever began, | ||

| − | Because it is an unchanging thing. | + | Because it is an [[unchanging]] thing. |

| − | If you agreed [that an unchanging thing could begin], then what we would answer to you is obvious. | + | If you agreed [that an [[unchanging]] thing could begin], then what we would answer to you is obvious. |

| − | Concerning the third of the original definitions, [that the definition of the future is: "that condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are present,"] we pose the following: | + | Concerning the third of the original definitions, [that the [[definition]] of the {{Wiki|future}} is: "that [[condition]] of having not yet begun, although the [[causes]] for beginning are {{Wiki|present}},"] we pose the following: |

| − | So is it true then that the future exists? | + | So is it true then that the {{Wiki|future}} [[exists]]? |

| − | Because it is something which has a definition; | + | Because it is something which has a [[definition]]; |

| − | Because “that condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are | + | Because “that [[condition]] of having not yet begun, although the [[causes]] for beginning are {{Wiki|present}}” is the [[definition]] of the {{Wiki|future}}. |

| − | You already agreed that the reason was true. | + | You already agreed that the [[reason]] was true. |

[Then I agree to your point above.] | [Then I agree to your point above.] | ||

| Line 257: | Line 257: | ||

Suppose you agree to the above. | Suppose you agree to the above. | ||

| − | So is it then the case that the future is itself? | + | So is it then the case that the {{Wiki|future}} is itself? |

| − | Because it does exist. | + | Because it does [[exist]]. |

| − | [I agree to your statement: the future is itself.] | + | [I agree to your statement: the {{Wiki|future}} is itself.] |

Suppose you agree to our original statement. | Suppose you agree to our original statement. | ||

| − | Consider the future. | + | Consider the {{Wiki|future}}. |

| − | So is it then a condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are present? | + | So is it then a [[condition]] of having not yet begun, although the [[causes]] for beginning are {{Wiki|present}}? |

| − | Because it is the future. | + | Because it is the {{Wiki|future}}. |

| − | You already agreed to the reason, | + | You already agreed to the [[reason]], |

| − | And it is obvious that the necessity must apply to the definition. | + | And it is obvious that the necessity must apply to the [[definition]]. |

[Then I agree.] | [Then I agree.] | ||

| Line 279: | Line 279: | ||

Suppose you agree. | Suppose you agree. | ||

| − | Depending on how they read this definition [in the Tibetan], some people claim, “I agree that the future is the condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are present (Tib: skye ba’i rgyu yod).” Others claim, “I agree that the object of our argument [the future] is the condition of having not yet begun, even though it has cause to begin from this same condition (Tib: skye ba’i rgyu yod).” | + | Depending on how they read this [[definition]] [in the [[Tibetan]]), some [[people]] claim, “I agree that the {{Wiki|future}} is the [[condition]] of having not yet begun, although the [[causes]] for beginning are {{Wiki|present}} (Tib: skye ba’i rgyu yod).” Others claim, “I agree that the [[object]] of our argument [the {{Wiki|future}}] is the [[condition]] of having not yet begun, even though it has [[cause]] to begin from this same [[condition]] (Tib: skye ba’i rgyu yod).” |

Well suppose then that you read it the first way. | Well suppose then that you read it the first way. | ||

| − | So does there exist a cause that makes the future begin? | + | So does there [[exist]] a [[cause]] that makes the {{Wiki|future}} begin? |

| − | Because the future is the condition of having not yet begun, even though the causes for beginning are present. | + | Because the {{Wiki|future}} is the [[condition]] of having not yet begun, even though the [[causes]] for beginning are {{Wiki|present}}. |

| − | You’ve already accepted the reason. | + | You’ve already accepted the [[reason]]. |

| − | [I agree that there does exist a cause that makes the future begin.] | + | [I agree that there does [[exist]] a [[cause]] that makes the {{Wiki|future}} begin.] |

Suppose you agree. | Suppose you agree. | ||

| − | So is this cause that makes the future begin a working thing? | + | So is this [[cause]] that makes the {{Wiki|future}} begin a working thing? |

| − | Because it does exist. | + | Because it does [[exist]]. |

[I agree that it is.] | [I agree that it is.] | ||

| Line 301: | Line 301: | ||

Suppose you agree. | Suppose you agree. | ||

| − | Consider this cause that makes the future begin. | + | Consider this [[cause]] that makes the {{Wiki|future}} begin. |

Is it something made? | Is it something made? | ||

| Line 317: | Line 317: | ||

Because it is something made. | Because it is something made. | ||

| − | You already agreed to the reason. | + | You already agreed to the [[reason]]. |

But you cannot agree, | But you cannot agree, | ||

| Line 323: | Line 323: | ||

Because it is something which has not yet begun; | Because it is something which has not yet begun; | ||

| − | Because it is the condition of having not yet begun; | + | Because it is the [[condition]] of having not yet begun; |

| − | Because it is a condition where, even though [its cause] exists, it has not yet begun. | + | Because it is a [[condition]] where, even though [its [[cause]]) [[exists]], it has not yet begun. |

| − | You’ve already agreed both to the reason and to what we’re asserting must be so. | + | You’ve already agreed both to the [[reason]] and to what we’re asserting must be so. |

| − | And the following problem applies to the latter way of reading the phrase. | + | And the following problem applies to the [[latter]] way of reading the [[phrase]]. |

| − | Is it then the case that this cause that will make it begin is a working thing? | + | Is it then the case that this [[cause]] that will make it begin is a working thing? |

| − | Because the cause that will make the future begin exists. | + | Because the [[cause]] that will make the {{Wiki|future}} begin [[exists]]. |

| − | [It's not correct to say that the cause that will make the future begin exists.] | + | [It's not correct to say that the [[cause]] that will make the {{Wiki|future}} begin [[exists]].] |

Suppose you say that it’s not correct. | Suppose you say that it’s not correct. | ||

| − | Consider this cause that will make the future begin. | + | Consider this [[cause]] that will make the {{Wiki|future}} begin. |

| − | It does so exist, | + | It does so [[exist]], |

| − | Because [the future] is a condition where, even though [its cause exists], it has not yet begun. | + | Because [the {{Wiki|future}}] is a [[condition]] where, even though [its [[cause]] [[exists]]), it has not yet begun. |

| − | You’ve already agreed both to the reason and to what we’re asserting must be so. | + | You’ve already agreed both to the [[reason]] and to what we’re asserting must be so. |

[It doesn't necessarily follow.] | [It doesn't necessarily follow.] | ||

| Line 355: | Line 355: | ||

Suppose you agree to our statement above. | Suppose you agree to our statement above. | ||

| − | Consider the cause that makes [the future] begin. | + | Consider the [[cause]] that makes [the {{Wiki|future}}] begin. |

It must then be something which has begun, | It must then be something which has begun, | ||

| Line 361: | Line 361: | ||

Because it is a working thing. | Because it is a working thing. | ||

| − | [I agree that the cause that makes the future begin is something which has begun.] | + | [I agree that the [[cause]] that makes the {{Wiki|future}} begin is something which has begun.] |

Suppose you agree. | Suppose you agree. | ||

| Line 371: | Line 371: | ||

Because it is a thing which has yet to begin, | Because it is a thing which has yet to begin, | ||

| − | Because it is a condition of not having yet begun. | + | Because it is a [[condition]] of not having yet begun. |

| − | [It's not correct to say that the cause which makes the future begin is a condition of not having yet begun.] | + | [It's not correct to say that the [[cause]] which makes the {{Wiki|future}} begin is a [[condition]] of not having yet begun.] |

Suppose you say that it’s not correct. | Suppose you say that it’s not correct. | ||

| − | Consider this cause that makes the future begin. | + | Consider this [[cause]] that makes the {{Wiki|future}} begin. |

| − | It is so the condition of not having yet begun, | + | It is so the [[condition]] of not having yet begun, |

| − | Because it is the condition of having not yet begun, even though it exists. | + | Because it is the [[condition]] of having not yet begun, even though it [[exists]]. |

| − | You’ve already both to the reason and to what we’re asserting must be so. | + | You’ve already both to the [[reason]] and to what we’re asserting must be so. |

_______________ | _______________ | ||

| Line 389: | Line 389: | ||

Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: | Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: | ||

| − | Does there exist a cause for something to begin or not? | + | Does there [[exist]] a [[cause]] for something to begin or not? |

We answer that there does, and then someone comes and makes the following claim: | We answer that there does, and then someone comes and makes the following claim: | ||

| − | But isn’t it the case that no cause for something to begin exists? | + | But isn’t it the case that no [[cause]] for something to begin [[exists]]? |

| − | Because isn’t it the case that nothing beginning exists? | + | Because isn’t it the case that nothing beginning [[exists]]? |

Because isn’t it the case that, if something is a working thing, it can never be beginning? | Because isn’t it the case that, if something is a working thing, it can never be beginning? | ||

| Line 409: | Line 409: | ||

So is it then the case that there are no beginnings at all? | So is it then the case that there are no beginnings at all? | ||

| − | Because none of the following exist: “something that’s going to begin,” “something that needs to begin,” “something that’s about to begin,” and “something that’s in the act of beginning.” | + | Because none of the following [[exist]]: “something that’s going to begin,” “something that needs to begin,” “something that’s about to begin,” and “something that’s in the act of beginning.” |

To this we say, “It doesn’t necessarily follow,” and then we say: | To this we say, “It doesn’t necessarily follow,” and then we say: | ||

| − | It’s like this. The beginning or the birth of something does too exist, | + | It’s like this. The beginning or the [[birth]] of something does too [[exist]], |

| − | Because past and future births exist. | + | Because {{Wiki|past}} and {{Wiki|future}} [[births]] [[exist]]. |

| − | And this is true because there exists the practice of amassing the two collections over a great many births, past and future. | + | And this is true because there [[exists]] the [[practice]] of amassing the [[two collections]] over a great many [[births]], {{Wiki|past}} and {{Wiki|future}}. |

| − | And this is true because there does exist the creation of an Infallible | + | And this is true because there does [[exist]] the creation of an Infallible |

| − | Being, who comes from the practice of amassing the two collections over a great many births, past and future. | + | Being, who comes from the [[practice]] of amassing the [[two collections]] over a great many [[births]], {{Wiki|past}} and {{Wiki|future}}. |

And this itself is true, because there is a point to the following two quotations: | And this itself is true, because there is a point to the following two quotations: | ||

| Line 431: | Line 431: | ||

And— | And— | ||

| − | The proof is that it comes from the practice | + | The [[proof]] is that it comes from the [[practice]] |

| − | Of the attitude of compassion. | + | Of the [[attitude]] of [[compassion]]. |

| − | [Both quotations are from the Commentary on Valid Perception, and are used to establish that an Enlightened Being is produced from many eons spent amassing the two collections.] | + | [Both quotations are from the Commentary on Valid [[Perception]], and are used to establish that an [[Enlightened Being]] is produced from many [[eons]] spent amassing the [[two collections]].] |

| − | Are you saying, moreover, that it is proper to throw away the whole system of those Lords of Reasoning, the Father and his spiritual Sons, and go following the system of that non-Buddhist school, the Rejectionists (Lokayata)? | + | Are you saying, moreover, that it is proper to throw away the whole system of those [[Lords]] of {{Wiki|Reasoning}}, the Father and his [[spiritual]] Sons, and go following the system of that [[non-Buddhist]] school, the Rejectionists ([[Wikipedia:Cārvāka|Lokayata]])? |

Because you would have to accept the other side as our side in the following verses: | Because you would have to accept the other side as our side in the following verses: | ||

| Line 445: | Line 445: | ||

Even things that are hidden, and there’s | Even things that are hidden, and there’s | ||

| − | No proof that shows he can; | + | No [[proof]] that shows he can; |

Neither is there a way to try.” | Neither is there a way to try.” | ||

| Line 455: | Line 455: | ||

And— | And— | ||

| − | Because the mind is something | + | Because the [[mind]] is something |

| − | That depends upon the body, | + | That depends upon the [[body]], |

There is nothing you can achieve | There is nothing you can achieve | ||

| − | Through practice [over many lifetimes]. | + | Through [[practice]] [over many lifetimes]. |

| − | And this is true because it would then be right for you to accept the position that it’s impossible for there to exist an enlightened realized being who has practiced assembling the two collections over a great many births, past and future. | + | And this is true because it would then be right for you to accept the position that it’s impossible for there to [[exist]] an [[enlightened]] [[realized]] being who has practiced assembling the [[two collections]] over a great many [[births]], {{Wiki|past}} and {{Wiki|future}}. |

_______________ | _______________ | ||

| Line 469: | Line 469: | ||

Suppose someone comes again and claims, | Suppose someone comes again and claims, | ||

| − | There must too exist a working thing which is about to begin, | + | There must too [[exist]] a working thing which is about to begin, |

| − | Because there exists a working thing which is about to take birth from their mother’s womb. | + | Because there [[exists]] a working thing which is about to take [[birth]] from their mother’s [[womb]]. |

| − | So does there exist then a working thing which is in the act of beginning? | + | So does there [[exist]] then a working thing which is in the act of beginning? |

| − | Because there exists a working which is about to take birth from their mother’s womb. | + | Because there [[exists]] a working which is about to take [[birth]] from their mother’s [[womb]]. |

The fact that it follows is something you find acceptable. | The fact that it follows is something you find acceptable. | ||

| − | But you cannot agree, because the glorious Chandrakirti has stated, “Since something in the act of beginning is only approaching beginning, it is not something which exists.” | + | But you cannot agree, because the glorious [[Chandrakirti]] has stated, “Since something in the act of beginning is only approaching beginning, it is not something which [[exists]].” |

| − | And are you, furthermore, saying that there exists a working thing which hasn’t begun? | + | And are you, furthermore, saying that there [[exists]] a working thing which hasn’t begun? |

| − | Because there exists a working thing which hasn’t begun, from their mother’s womb. | + | Because there [[exists]] a working thing which hasn’t begun, from their mother’s [[womb]]. |

| − | Suppose someone comes and says, “It’s incorrect [to say that there exists a working thing which hasn't begun, from their mother's womb]. | + | Suppose someone comes and says, “It’s incorrect [to say that there [[exists]] a working thing which hasn't begun, from their mother's [[womb]]). |

| − | But it is correct, because (1) there does exist a person who is in the act of staying in their mother’s womb, and (2) there also exists a working thing which is born complete. | + | But it is correct, because (1) there does [[exist]] a [[person]] who is in the act of staying in their mother’s [[womb]], and (2) there also [[exists]] a working thing which is born complete. |

Are you saying, moreover, that a working thing which has already begun begins again? | Are you saying, moreover, that a working thing which has already begun begins again? | ||

| − | Because there exists a living being who has already taken birth, and who has to take birth again. | + | Because there [[exists]] a [[living being]] who has already taken [[birth]], and who has to take [[birth]] again. |

| − | And this is true because there exists a living being who has already taken birth, and who has to take birth again in the circle of suffering life. | + | And this is true because there [[exists]] a [[living being]] who has already taken [[birth]], and who has to take [[birth]] again in the circle of [[suffering]] [[life]]. |

| − | And this is true because (1) there exists a living being who has already taken birth as a human, and who has to take birth again as a human; and (2) there exists a living being who has already taken birth into the desire realm, and who has to take birth into the desire realm again. | + | And this is true because (1) there [[exists]] a [[living being]] who has already taken [[birth]] as a [[human]], and who has to take [[birth]] again as a [[human]]; and (2) there [[exists]] a [[living being]] who has already taken [[birth]] into the [[desire realm]], and who has to take [[birth]] into the [[desire realm]] again. |

| − | Each of the reasons given is correct, because there do exist those who come from a birth as a human and are born as a human; and there do exist those who come from a birth in the desire realm and are born into the desire realm. It’s easy to accept these reasons. | + | Each of the [[reasons]] given is correct, because there do [[exist]] those who come from a [[birth]] as a [[human]] and are born as a [[human]]; and there do [[exist]] those who come from a [[birth]] in the [[desire realm]] and are born into the [[desire realm]]. It’s easy to accept these [[reasons]]. |

| − | And is it, moreover, the case that there exists nothing which is occurring? | + | And is it, moreover, the case that there [[exists]] nothing which is occurring? |

Because nothing which is a working thing could ever be something which is occurring. | Because nothing which is a working thing could ever be something which is occurring. | ||

| Line 507: | Line 507: | ||

The fact that it follows is something you find acceptable. | The fact that it follows is something you find acceptable. | ||

| − | The reason we’ve stated is correct, because anything which is a working thing is something which has already occurred from its own causes. | + | The [[reason]] we’ve stated is correct, because anything which is a working thing is something which has already occurred from its [[own]] [[causes]]. |

| − | And this is true because anything which is a working thing is something which has already begun from its own causes. | + | And this is true because anything which is a working thing is something which has already begun from its [[own]] [[causes]]. |

| − | [Then I agree to your original statement: it is the case that there exists nothing which is occurring.] | + | [Then I agree to your original statement: it is the case that there [[exists]] nothing which is occurring.] |

Suppose you agree to our original statement. | Suppose you agree to our original statement. | ||

| − | There does too exist something which is occurring, | + | There does too [[exist]] something which is occurring, |

| − | Because there exist the four great elements. | + | Because there [[exist]] the [[four great elements]]. |

| − | And this is because there do exist the four of earth, water, fire, and wind. | + | And this is because there do [[exist]] the four of [[earth]], [[water]], [[fire]], and [[wind]]. |

| − | [Translator's note: This argument depends upon the fact that the Tibetan words for "occurring" and for "element" have the same spelling ('byung ba).] | + | [Translator's note: This argument depends upon the fact that the [[Tibetan]] words for "occurring" and for "[[element]]" have the same spelling ('byung ba).] |

[It doesn't necessarily follow.] | [It doesn't necessarily follow.] | ||

| − | It does necessarily follow, because that highest master, Vasubandhu, has stated that the great elements are four. | + | It does necessarily follow, because that [[highest]] [[master]], [[Vasubandhu]], has stated that the [[great elements]] are four. |

| − | And this is true because the Treasure House says, | + | And this is true because the [[Treasure]] House says, |

| − | The elements are the following: | + | The [[elements]] are the following: |

| − | The divisions of elements we call | + | The divisions of [[elements]] we call |

| − | Earth and water and fire and wind. | + | [[Earth]] and [[water]] and [[fire]] and [[wind]]. |

_______________ | _______________ | ||

| − | Suppose yet another person comes and claims: | + | Suppose yet another [[person]] comes and claims: |

| − | There must too exist a working thing which still has to start, | + | There must too [[exist]] a working thing which still has to start, |

| − | Because there does exist a working thing which is going to start. | + | Because there does [[exist]] a working thing which is going to start. |

| − | And this is because there does exist a working thing which is going to occur. | + | And this is because there does [[exist]] a working thing which is going to occur. |

To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | ||

| − | The reason in itself though does apply to the subject, | + | The [[reason]] in itself though does apply to the [[subject]], |

| − | Because the four of blue, yellow, white, and red and the like are all derivatives of the elements, and there also exist tangible objects which are derivatives of the elements. | + | Because the four of blue, yellow, white, and red and the like are all derivatives of the [[elements]], and there also [[exist]] {{Wiki|tangible}} [[objects]] which are derivatives of the [[elements]]. |

| − | And this is true because all tangible objects can be divided into two types: those that are elements, and those that are derivatives of the elements. | + | And this is true because all {{Wiki|tangible}} [[objects]] can be divided into two types: those that are [[elements]], and those that are derivatives of the [[elements]]. |

| − | [Translator's note: This argument depends on the fact that the Tibetan for "going to occur" and for "derivative of the elements" is the same ('byung-'gyur).] | + | [Translator's note: This argument depends on the fact that the [[Tibetan]] for "going to occur" and for "derivative of the [[elements]]" is the same ('byung-'gyur).] |

| − | And this is true because The Treasure House of Wisdom says, | + | And this is true because The [[Treasure]] House of [[Wisdom]] says, |

| − | Tangible objects are of two types… | + | {{Wiki|Tangible}} [[objects]] are of two types… |

| − | You can’t though agree to the original statement, [that there must exist a working thing which still has to start], | + | You can’t though agree to the original statement, [that there must [[exist]] a working thing which still has to start], |

Because anything which is a working thing is something which must have already started. | Because anything which is a working thing is something which must have already started. | ||

| Line 565: | Line 565: | ||

On this point some may make the following claim: | On this point some may make the following claim: | ||

| − | It must so be the case that there exists no working thing which is going to occur, | + | It must so be the case that there [[exists]] no working thing which is going to occur, |

Because anything which is a working thing must have already occurred. | Because anything which is a working thing must have already occurred. | ||

| − | This position though reflects a gross error of failing to examine things thoroughly. The expressions “going to start” and “still needs to start” are equivalent in meaning, exclusively, “going to start from the beginning” and “still needs to start from the beginning.” | + | This position though reflects a gross error of failing to examine things thoroughly. The {{Wiki|expressions}} “going to start” and “still needs to start” are {{Wiki|equivalent}} in meaning, exclusively, “going to start from the beginning” and “still needs to start from the beginning.” |

| − | But whereas “still needs to occur” means, exclusively, “still needs to occur from the beginning,” the [Tibetan phrase for] “going to occur” also applies to things which have already occurred, such as the color blue, or the tangible objects of heat or cold, and so on. And the mistake by the opponent here is that they have never heard the terms explained this way. | + | But whereas “still needs to occur” means, exclusively, “still needs to occur from the beginning,” the ([[Tibetan]] [[phrase]] for] “going to occur” also applies to things which have already occurred, such as the {{Wiki|color}} blue, or the {{Wiki|tangible}} [[objects]] of heat or cold, and so on. And the mistake by the opponent here is that they have never heard the terms explained this way. |

_______________ | _______________ | ||

| Line 577: | Line 577: | ||

Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: | Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: | ||

| − | The definition of something | + | The [[definition]] of something “{{Wiki|past}}” [[relative]] to the [[time]] of a [[water]] pitcher is “that which has started and also stopped, in the [[time]] that the [[water]] pitcher is {{Wiki|present}}.” |

| − | The definition of something | + | The [[definition]] of something “{{Wiki|future}}” [[relative]] to the [[time]] of a [[water]] pitcher is “that which is such that—although the [[causes]] for it to start are already present—it has yet to start, in the [[time]] that the [[water]] pitcher is {{Wiki|present}}.” |

| − | The definition of something | + | The [[definition]] of something “{{Wiki|present}}” [[relative]] to the [[time]] of a [[water]] pitcher is “that which has started and not yet stopped, in the [[time]] that the [[water]] pitcher is {{Wiki|present}}.” |

Let us address the first of these definitions. | Let us address the first of these definitions. | ||

| − | Consider the cause of a water pitcher. | + | Consider the [[cause]] of a [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | Is this cause then something which has started and also stopped, in the time that the water pitcher is present? | + | Is this [[cause]] then something which has started and also stopped, in the [[time]] that the [[water]] pitcher is {{Wiki|present}}? |

| − | Because it is something which is past relative to the time of the water pitcher. | + | Because it is something which is {{Wiki|past}} [[relative]] to the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher. |

And this is because it is the example we’ve chosen here. | And this is because it is the example we’ve chosen here. | ||

| − | And suppose you agree to the previous statement. [That is, suppose you agree that the cause of a water pitcher is something which has started and also stopped in the time of the water pitcher.] | + | And suppose you agree to the previous statement. [That is, suppose you agree that the [[cause]] of a [[water]] pitcher is something which has started and also stopped in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher.] |

| − | Consider again the cause of a water pitcher. | + | Consider again the [[cause]] of a [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | Is it then one thing which has both (1) started in the time of the water pitcher and (2) stopped in the time of the water pitcher? | + | Is it then one thing which has both (1) started in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher and (2) stopped in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher? |

[Why do you say that?] | [Why do you say that?] | ||

| Line 603: | Line 603: | ||

Because you agreed. | Because you agreed. | ||

| − | [Then I agree that the cause of a water pitcher is one thing which has both (1) started in the time of the water pitcher and (2) stopped in the time of the water pitcher.] | + | [Then I agree that the [[cause]] of a [[water]] pitcher is one thing which has both (1) started in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher and (2) stopped in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher.] |

Suppose you agree then. | Suppose you agree then. | ||

| Line 609: | Line 609: | ||

Consider this same thing. | Consider this same thing. | ||

| − | Is it then something which has started in the time of the water pitcher? | + | Is it then something which has started in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher? |

[Why do you say that?] | [Why do you say that?] | ||

| Line 615: | Line 615: | ||

Because you agreed above. | Because you agreed above. | ||

| − | And yet you can’t agree, because it is something which has not started in the time of the water pitcher. | + | And yet you can’t agree, because it is something which has not started in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | And this is because it is something which has not been made in the time of the water pitcher. | + | And this is because it is something which has not been made in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | [It's not necessarily the case that, because the cause of a pitcher is something which has not been made in the time of the water pitcher, it must be something which has not started in the time of the water pitcher.] | + | [It's not necessarily the case that, because the [[cause]] of a pitcher is something which has not been made in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher, it must be something which has not started in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher.] |

Suppose you say that it’s not necessarily the case. | Suppose you say that it’s not necessarily the case. | ||

| Line 625: | Line 625: | ||

It is though necessarily the case, | It is though necessarily the case, | ||

| − | Because the very definition of something’s not having been made in a certain time is “something’s not having started” in that same time. | + | Because the very [[definition]] of something’s not having been made in a certain [[time]] is “something’s not having started” in that same [[time]]. |

| − | And this is true because (1) there is at that time something which hasn’t been made, and (2) the definition of “something that hasn’t been made” is “something that hasn’t started.” | + | And this is true because (1) there is at that [[time]] something which hasn’t been made, and (2) the [[definition]] of “something that hasn’t been made” is “something that hasn’t started.” |

| − | And this is true because “something that has started” is the definition of “something that has been made.” | + | And this is true because “something that has started” is the [[definition]] of “something that has been made.” |

| − | Now suppose that you were to answer “it’s not correct to say that” above, where you answered “it doesn’t’ necessarily follow.” [That is, suppose you say that it's not correct to say that the cause of a water pitcher is something which has not been made in the time of the water pitcher.] | + | Now suppose that you were to answer “it’s not correct to say that” above, where you answered “it doesn’t’ necessarily follow.” [That is, suppose you say that it's not correct to say that the [[cause]] of a [[water]] pitcher is something which has not been made in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher.] |

Consider this same thing. | Consider this same thing. | ||

| − | It is so true that it has not been made in that particular time, | + | It is so true that it has not been made in that particular [[time]], |

| − | Because it doesn’t even exist in that particular time. | + | Because it doesn’t even [[exist]] in that particular [[time]]. |

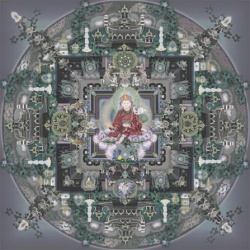

[[File:Ma-buddha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Ma-buddha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | And this is because it has stopped in that particular time. | + | And this is because it has stopped in that particular [[time]]. |

| − | And this is because, in that particular time, it has started and also stopped. | + | And this is because, in that particular [[time]], it has started and also stopped. |

| − | And you’ve already agreed to what we stated as our reason. | + | And you’ve already agreed to what we stated as our [[reason]]. |

| − | Consider, moreover, the cause of a water pitcher, once again. | + | Consider, moreover, the [[cause]] of a [[water]] pitcher, once again. |

| − | It is not so, that it is one thing which has both (1) started in the time of the water pitcher, and (2) stopped in this same time, | + | It is not so, that it is one thing which has both (1) started in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher, and (2) stopped in this same [[time]], |

Because it is not something which has stopped. | Because it is not something which has stopped. | ||

| Line 657: | Line 657: | ||

_______________ | _______________ | ||

| − | Suppose yet another person comes, and makes this claim: | + | Suppose yet another [[person]] comes, and makes this claim: |

| − | Consider the cause of a water pitcher. | + | Consider the [[cause]] of a [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | It is too something which has started in the time of the water pitcher, | + | It is too something which has started in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher, |

| − | Because it has finished starting in the time of the water pitcher. | + | Because it has finished starting in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher. |

To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | ||

| − | Therefore we have to express the situation as follows: Although the cause of the water pitcher, in the time of the water pitcher, has already begun, it is not something which has begun in the time of the water pitcher. This is for example like the case where the followers of the Independent group of the Middle-Way School and such say that | + | Therefore we have to express the situation as follows: Although the [[cause]] of the [[water]] pitcher, in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher, has already begun, it is not something which has begun in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher. This is for example like the case where the followers of the Independent group of the [[Middle-Way]] School and such say that “[[Cause and effect]] is true [Tib: bden-pa], but not real [Tib: bden-pa].” You have to be able to make the same kind of {{Wiki|distinction}} here. |

____________ | ____________ | ||

| Line 673: | Line 673: | ||

Suppose someone comes along and claims, | Suppose someone comes along and claims, | ||

| − | Even though omniscience perceives a water pitcher directly, it does not do so in the sense that the word “directly” has when we divide perception into the two of “direct” and | + | Even though [[omniscience]] [[perceives]] a [[water]] pitcher directly, it does not do so in the [[sense]] that the [[word]] “directly” has when we divide [[perception]] into the two of “direct” and “{{Wiki|deductive}}.” |

To this we answer, “You are absolutely correct.” | To this we answer, “You are absolutely correct.” | ||

| − | If however someone were to come along in a debate and say that “Every state of direct perception is ‘direct’ in the sense that this word has when we divide perception into the two of ‘direct’ and | + | If however someone were to come along in a [[debate]] and say that “Every [[state]] of direct [[perception]] is ‘direct’ in the [[sense]] that this [[word]] has when we divide [[perception]] into the two of ‘direct’ and ‘{{Wiki|deductive}}’,” some [[logic]] would be required to prove the point just made. |

____________ | ____________ | ||

| − | As for the second definition, [the definition of "the future" given above,] consider the result of a water pitcher. | + | As for the second [[definition]], [the [[definition]] of "the {{Wiki|future}}" given above,] consider the result of a [[water]] pitcher. |

Is it then something that has not begun? | Is it then something that has not begun? | ||

| − | Because it is the condition of not having begun. | + | Because it is the [[condition]] of not having begun. |

| − | And this is because it is the condition of not having begun, even though the causes for its beginning exist in the time of the water pitcher. | + | And this is because it is the [[condition]] of not having begun, even though the [[causes]] for its beginning [[exist]] in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | Now some may come along and claim, in response, that “it doesn’t necessarily follow.” This however would indicate that they had yet to grasp the meaning of the collected topics on logic and perception. | + | Now some may come along and claim, in response, that “it doesn’t necessarily follow.” This however would indicate that they had yet to [[grasp]] the meaning of the [[collected topics]] on [[logic]] and [[perception]]. |

| − | Suppose someone else came and said, instead, that “Your reason is not correct.” | + | Suppose someone else came and said, instead, that “Your [[reason]] is not correct.” |

| − | Consider then this same thing: [the result of a water pitcher]. | + | Consider then this same thing: [the result of a [[water]] pitcher]. |

| − | Are you saying that it is the condition of not having begun, even though, in the time of the pitcher, the causes for its beginning are present? Because it is “the | + | Are you saying that it is the [[condition]] of not having begun, even though, in the [[time]] of the pitcher, the [[causes]] for its beginning are {{Wiki|present}}? Because it is “the {{Wiki|future}}” at this same [[time]]. |

| − | The correctness of our reason is easy to accept. | + | The correctness of our [[reason]] is easy to accept. |

And you’ve already accepted the necessity. | And you’ve already accepted the necessity. | ||

| − | As for the third of the definitions above, [that of "the present,"] suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: | + | As for the third of the definitions above, [that of "the {{Wiki|present}},"] suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: |

| − | Consider the cause of a water pitcher. | + | Consider the [[cause]] of a [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | It is so something which is present-time in the time of the water pitcher, | + | It is so something which is present-time in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher, |

| − | Because it is something which, in the time of the water pitcher, has begun and not yet stopped. | + | Because it is something which, in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher, has begun and not yet stopped. |

| − | It is so, because it is both (1) something which has begun in the time of the water pitcher and (2) something which has not stopped in that time. | + | It is so, because it is both (1) something which has begun in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher and (2) something which has not stopped in that [[time]]. |

| − | Our side would answer that the first part of this reason is not correct. | + | Our side would answer that the first part of this [[reason]] is not correct. |

And then the other side would come back with, | And then the other side would come back with, | ||

| Line 717: | Line 717: | ||

Consider then this same thing. | Consider then this same thing. | ||

| − | It is too something which has begun in the time of the water pitcher, | + | It is too something which has begun in the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher, |

| − | Because it is something which has finished beginning in that time. | + | Because it is something which has finished beginning in that [[time]]. |

To this we’d answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | To this we’d answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | ||

| Line 725: | Line 725: | ||

*************** | *************** | ||

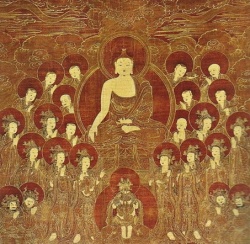

| − | Here next is an analysis of the question of whether the past and the future exist or not. Generally speaking there exist no definitions for “the | + | Here next is an analysis of the question of whether the {{Wiki|past}} and the {{Wiki|future}} [[exist]] or not. Generally {{Wiki|speaking}} there [[exist]] no definitions for “the {{Wiki|past}}” or “the {{Wiki|future}},” because the {{Wiki|past}} and {{Wiki|future}} are not things which even [[exist]]. This is because, anything which can be established as [[existing]] must always be [[existing]] in the {{Wiki|present}} [according to this school of [[Buddhism]]). |

| − | If though we were to establish the meaning of “the | + | If though we were to establish the meaning of “the {{Wiki|past}}” [[relative]] to a specific point of reference, we could say that the [[definition]] of its {{Wiki|past}} [[relative]] to the [[time]] of a specific [[water]] pitcher could be given as follows: |

| − | Something which has, by the time of the water pitcher, already started; and which has, by the time of the water pitcher, already ended as well. | + | Something which has, by the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher, already started; and which has, by the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher, already ended as well. |

This and “the pitcher just before the pitcher” amount to the same thing. | This and “the pitcher just before the pitcher” amount to the same thing. | ||

| − | The definition of its present relative to the time of a specific water pitcher then could be given as follows: | + | The [[definition]] of its {{Wiki|present}} [[relative]] to the [[time]] of a specific [[water]] pitcher then could be given as follows: |

| − | That one thing which is both (1) something which has already come into existence by the time of the water pitcher; and (2) which is simultaneous to the water pitcher. | + | That one thing which is both (1) something which has already come into [[existence]] by the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher; and (2) which is simultaneous to the [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | The definition of its future relative to the time of a specific water pitcher, finally, could be given as follows: | + | The [[definition]] of its {{Wiki|future}} [[relative]] to the [[time]] of a specific [[water]] pitcher, finally, could be given as follows: |

| − | That one thing which is both (1) in the act of starting at the time of the water pitcher; and (2) not yet started at the time of the water pitcher. | + | That one thing which is both (1) in the act of starting at the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher; and (2) not yet started at the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher. |

The following all amount to the same thing: | The following all amount to the same thing: | ||

| − | the not-yet-coming of the water pitcher; | + | the not-yet-coming of the [[water]] pitcher; |

| − | the cause of the water pitcher; | + | the [[cause]] of the [[water]] pitcher; |

| − | its past at the time of the water pitcher; and | + | its {{Wiki|past}} at the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher; and |

| − | its past relative to the water pitcher. | + | its {{Wiki|past}} [[relative]] to the [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | [Translator's note: "Not-yet-coming" and "future" are the same word in Tibetan (ma- 'ongs-pa).] | + | [Translator's note: "Not-yet-coming" and "{{Wiki|future}}" are the same [[word]] in [[Tibetan]] (ma- 'ongs-pa).] |

The following also all amount to the same thing: | The following also all amount to the same thing: | ||

| − | the passing of the water pitcher; | + | the passing of the [[water]] pitcher; |

| − | the result of the water pitcher; | + | the result of the [[water]] pitcher; |

| − | its future at the time of the water pitcher; and | + | its {{Wiki|future}} at the [[time]] of the [[water]] pitcher; and |

| − | its future relative to the water pitcher. | + | its {{Wiki|future}} [[relative]] to the [[water]] pitcher. |

| − | [Translator's note: "Passing" and "past" are the same word in Tibetan ('das-pa).] | + | [Translator's note: "Passing" and "{{Wiki|past}}" are the same [[word]] in [[Tibetan]] ('das-pa).] |

| − | Generally speaking, there is no such thing as something which has stopped. | + | Generally {{Wiki|speaking}}, there is no such thing as something which has stopped. |

| − | And there is nothing which is about to begin. Neither is there anything which is in the act of beginning, nor is there anything which is approaching the state of beginning. | + | And there is nothing which is about to begin. Neither is there anything which is in the act of beginning, nor is there anything which is approaching the [[state]] of beginning. |

| − | There does exist though the passing of the smoke; and the stopping of the smoke; and the smoke’s not yet coming, and the smoke’s being about to begin; and the smoke’s being in the act of beginning; and the smoke’s approaching the state of beginning. | + | There does [[exist]] though the passing of the smoke; and the stopping of the smoke; and the smoke’s not yet coming, and the smoke’s being about to begin; and the smoke’s being in the act of beginning; and the smoke’s approaching the [[state]] of beginning. |

| − | There is though no such thing as smoke which is approaching the state of beginning. Neither is there any smoke which is in the act of beginning; nor any smoke which is about to begin; nor smoke which has stopped; nor smoke which has been destroyed; nor smoke which is past; nor smoke which is future. | + | There is though no such thing as smoke which is approaching the [[state]] of beginning. Neither is there any smoke which is in the act of beginning; nor any smoke which is about to begin; nor smoke which has stopped; nor smoke which has been destroyed; nor smoke which is {{Wiki|past}}; nor smoke which is {{Wiki|future}}. |

The following all amount to the same thing: | The following all amount to the same thing: | ||

| Line 783: | Line 783: | ||

a thing which is in the act of being destroyed; | a thing which is in the act of being destroyed; | ||

| − | a thing which is approaching the past; | + | a thing which is approaching the {{Wiki|past}}; |

[[File:Nanda devatas.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Nanda devatas.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

a thing which is approaching its destruction. | a thing which is approaching its destruction. | ||

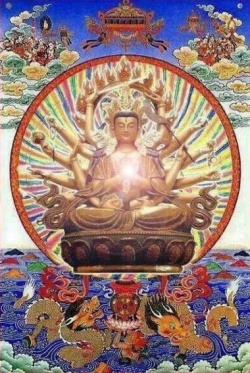

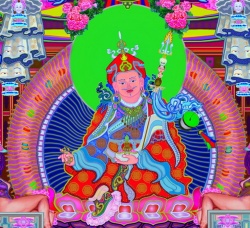

| − | These assertions [about the nature of time] are all presented in accordance with the beliefs of the | + | These assertions [about the [[nature]] of [[time]]) are all presented in accordance with the [[beliefs]] of the “[[Logician]]” group within the Sutrist School. They would not necessarily be acceptable to any other school of [[Buddhism]]. The Detailists, for example, do accept [[ideas]] such as {{Wiki|past}} [[karma]] and {{Wiki|future}} [[karma]], while the Necessity group entertains unimaginably profound positions such as the one that states that the destruction of something is a working thing. |

*************** | *************** | ||

| Line 793: | Line 793: | ||

| − | Formal logic subject: | + | {{Wiki|Formal logic}} [[subject]]: |

| − | A Discussion of Incorrect Logical Statements | + | A [[Discussion]] of Incorrect [[Logical]] Statements |

| − | The following presentation on incorrect | + | The following presentation on incorrect “[[logical]]” statements is excerpted from An Explanation of the [[Art]] of {{Wiki|Reasoning}} ([[rTags-rigs]]), by the Tutor of [[His Holiness]] the [[Thirteenth Dalai Lama]], Purbuchok [[Jampa]] [[Tsultrim Gyatso]] (1825-1901). |

_______________ | _______________ | ||

| − | Here is the second major division of our presentation, in which we explain the opposite of a correct reason: that is, incorrect reasons. We proceed in two steps: the definition of such reasons, and their various divisions. | + | Here is the second major [[division]] of our presentation, in which we explain the opposite of a correct [[reason]]: that is, incorrect [[reasons]]. We proceed in two steps: the [[definition]] of such [[reasons]], and their various divisions. |

| − | The first of these we’ll discuss in terms of disproving our opponent’s beliefs, and then establishing our own beliefs. Here is the first. Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: “Any reason where the three relationships fail to hold” is the definition of an incorrect reason. | + | The first of these we’ll discuss in terms of disproving our opponent’s [[beliefs]], and then establishing our [[own]] [[beliefs]]. Here is the first. Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: “Any [[reason]] where the three relationships fail to hold” is the [[definition]] of an incorrect [[reason]]. |

| − | This though is mistaken, for there is no such thing as an incorrect reason: everything which exists is a correct reason [to prove something]. | + | This though is mistaken, for there is no such thing as an incorrect [[reason]]: everything which [[exists]] is a correct [[reason]] [to prove something]. |

| − | Here secondly is our own position. The definition of an incorrect reason for a particular proof is: | + | Here secondly is our [[own]] position. The [[definition]] of an incorrect [[reason]] for a particular [[proof]] is: |

| − | A reason for a particular proof where the three relationships fail to hold. | + | A [[reason]] for a particular [[proof]] where the three relationships fail to hold. |

| − | Here secondly are the various divisions of incorrect reasons. Although there is not, generally speaking, any such thing as an incorrect reason, we can say that there do exist the following types of incorrect reasons in specific contexts: | + | Here secondly are the various divisions of incorrect [[reasons]]. Although there is not, generally {{Wiki|speaking}}, any such thing as an incorrect [[reason]], we can say that there do [[exist]] the following types of incorrect [[reasons]] in specific contexts: |

| − | 1) Contradictory reasons for specific proofs; | + | 1) [[Contradictory]] [[reasons]] for specific proofs; |

| − | 2) Indefinite reasons for specific proofs; and | + | 2) Indefinite [[reasons]] for specific proofs; and |

| − | 3) Wrong reasons for specific proofs. | + | 3) Wrong [[reasons]] for specific proofs. |

| − | We will discuss the first of these in four steps: definition; divisions; classical examples; and supporting arguments. | + | We will discuss the first of these in four steps: [[definition]]; divisions; classical examples; and supporting arguments. |

| − | Here is the first. The definition of a contradictory reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing is: | + | Here is the first. The [[definition]] of a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] for proving that [[sound]] is an [[unchanging]] thing is: |

| − | That one thing for which (1) the relationship between the subject and the reason does hold for proving that sound is an unchanging thing; and (2) the positive necessity between the reason and the quality to be proven also holds for proving that sound is not an unchanging thing. | + | That one thing for which (1) the relationship between the [[subject]] and the [[reason]] does hold for proving that [[sound]] is an [[unchanging]] thing; and (2) the positive necessity between the [[reason]] and the quality to be proven also holds for proving that [[sound]] is not an [[unchanging]] thing. |

| − | [A classical example would be: Consider sound. It is an unchanging thing, because it is a made thing.] | + | [A classical example would be: Consider [[sound]]. It is an [[unchanging]] thing, because it is a made thing.] |

Here secondly are the divisions. | Here secondly are the divisions. | ||

| − | Contradictory reasons can be divided into two kinds: those which have a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they cover it completely, and those which have a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they go both ways, [covering or not]. | + | [[Contradictory]] [[reasons]] can be divided into two kinds: those which have a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they cover it completely, and those which have a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they go both ways, [covering or not]. |

| − | Here thirdly are the classical examples. “Something that was made” is a contradictory reason which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they cover it completely, in a proof that sound is not a changing thing. “Something which is a particular example of the general type called ‘made things’” is a contradictory reason which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they go both ways, in proving the same thing. | + | Here thirdly are the classical examples. “Something that was made” is a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they cover it completely, in a [[proof]] that [[sound]] is not a changing thing. “Something which is a particular example of the general type called ‘made things’” is a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they go both ways, in proving the same thing. |

Next is the fourth category: the supporting arguments. | Next is the fourth category: the supporting arguments. | ||

| Line 839: | Line 839: | ||

Consider “something that was made.” | Consider “something that was made.” | ||

| − | It is so a contradictory reason which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they cover it completely, in a proof that sound is not a changing thing, | + | It is so a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they cover it completely, in a [[proof]] that [[sound]] is not a changing thing, |

| − | Because it is both (1) a contradictory reason for proving this particular thing, and (2) anything which is changing is also it. | + | Because it is both (1) a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] for proving this particular thing, and (2) anything which is changing is also it. |

And consider “something which is a particular example of the general type called ‘made things’.” | And consider “something which is a particular example of the general type called ‘made things’.” | ||

| − | It is so a contradictory reason which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they go both ways, in a proof that sound is not a changing thing, | + | It is so a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they go both ways, in a [[proof]] that [[sound]] is not a changing thing, |

| − | Because it is a contradictory reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing. | + | Because it is a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] for proving that [[sound]] is an [[unchanging]] thing. |

| − | And this is so because (1) the relationship between this reason and the subject of the particular proof holds; and (2) it is definitely the case that the positive necessity between it and the quality to be proven is diametrically false. | + | And this is so because (1) the relationship between this [[reason]] and the [[subject]] of the particular [[proof]] holds; and (2) it is definitely the case that the positive necessity between it and the quality to be proven is diametrically false. |

Consider, moreover, this same example. | Consider, moreover, this same example. | ||

| − | It is so a contradictory reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing, | + | It is so a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] for proving that [[sound]] is an [[unchanging]] thing, |

| − | Because it is a correct reason for proving that sound is a changing thing. | + | Because it is a correct [[reason]] for proving that [[sound]] is a changing thing. |

_______________ | _______________ | ||

| Line 861: | Line 861: | ||

Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: | Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: | ||

| − | So does there exist then a contradictory reason for proving that sound is a changing thing? | + | So does there [[exist]] then a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] for proving that [[sound]] is a changing thing? |

| − | Because there does exist a contradictory reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing. | + | Because there does [[exist]] a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] for proving that [[sound]] is an [[unchanging]] thing. |

To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.” | ||

| − | And you could never agree [that there did exist a contradictory reason for proving that sound is a changing thing], | + | And you could never agree [that there did [[exist]] a [[contradictory]] [[reason]] for proving that [[sound]] is a changing thing], |

| − | Because anything which is an incorrect reason for proving that sound is a changing thing must be either (1) an indefinite reason for the particular proof or (2) a wrong reason for the particular proof. | + | Because anything which is an incorrect [[reason]] for proving that [[sound]] is a changing thing must be either (1) an indefinite [[reason]] for the particular [[proof]] or (2) a wrong [[reason]] for the particular [[proof]]. |

____________ | ____________ | ||

| Line 875: | Line 875: | ||

Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: | Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: | ||

| − | If there exist the three relationships for any particular proof, then there must exist a correct reason for the particular proof. | + | If there [[exist]] the three relationships for any particular [[proof]], then there must [[exist]] a correct [[reason]] for the particular [[proof]]. |

Consider all knowable things. | Consider all knowable things. | ||

| − | There must then exist a correct reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing, | + | There must then [[exist]] a correct [[reason]] for proving that [[sound]] is an [[unchanging]] thing, |

| − | Because the three relationships do exist for proving that sound is an unchanging thing. | + | Because the three relationships do [[exist]] for proving that [[sound]] is an [[unchanging]] thing. |

You’ve already accepted that it necessarily follows. | You’ve already accepted that it necessarily follows. | ||

| − | Suppose then that you say that it’s not correct [that the three relationships do exist for proving that sound is an unchanging thing]. | + | Suppose then that you say that it’s not correct [that the three relationships do [[exist]] for proving that [[sound]] is an [[unchanging]] thing]. |

| − | They do too exist, because (1) there exists a relationship between the reason and the subject for this particular proof, and (2) there exists the positive necessity for the proof, and there exists the reverse necessity for the proof. | + | They do too [[exist]], because (1) there [[exists]] a relationship between the [[reason]] and the [[subject]] for this particular [[proof]], and (2) there [[exists]] the positive necessity for the [[proof]], and there [[exists]] the reverse necessity for the [[proof]]. |