Difference between revisions of "Sahaja"

m (Text replacement - "]]]" to "]])") |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

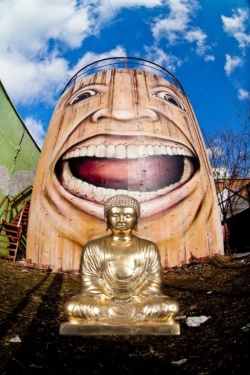

| − | [[File:Sb39.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | + | [[File:Sb39.jpg|thumb|250px|]]<nomobile>{{DisplayImages|3718|2934|2401|4218|2799|2898}}</nomobile> |

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

The [[Victorious Ones]] are filled with {{Wiki|perfect}} [qualities], | The [[Victorious Ones]] are filled with {{Wiki|perfect}} [qualities], | ||

Which all have the very same nature——spontaneous presence. | Which all have the very same nature——spontaneous presence. | ||

| − | From [the natural display of the great [[sphere]] | + | From [the natural display of the great [[sphere]]), [[living beings]] take [[birth]] and therein cease. |

In [[relation]] to this, there is no thing and no nonthing. | In [[relation]] to this, there is no thing and no nonthing. | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

It influenced the [[bhakti]] {{Wiki|movement}} through the Sant [[tradition]], exemplified by the Bauls of {{Wiki|Bengal}}, Dnyaneshwar, Meera, {{Wiki|Kabir}} and [[Guru Nanak]], the founder of [[Sikhism]]. | It influenced the [[bhakti]] {{Wiki|movement}} through the Sant [[tradition]], exemplified by the Bauls of {{Wiki|Bengal}}, Dnyaneshwar, Meera, {{Wiki|Kabir}} and [[Guru Nanak]], the founder of [[Sikhism]]. | ||

| − | [[Yoga]] in particular had a quickening influence on the various Sahajiya [[traditions]]. The {{Wiki|culture}} of the [[body]] (kāya-sādhana) through {{Wiki|processes}} of [[Haṭha-yoga]] was of paramount importance in the [[Nāth]] [[sect]] and found in all [[sahaja]] schools. Whether [[conceived]] of as '[[supreme bliss]]' ([[Mahā-sukha]]), as by the [[Buddhist]] [[Sahajiyās]], or as '[[supreme love]]' (as with the [[Vaiṣṇava]] [[Sahajiyās]]), strength of the [[body]] was deemed necessary to stand such a supreme realisation. | + | [[Yoga]] in particular had a quickening influence on the various ]]Sahajiya\\ [[traditions]]. The {{Wiki|culture}} of the [[body]] (]]kāya-sādhana\\) through {{Wiki|processes}} of [[Haṭha-yoga]] was of paramount importance in the [[Nāth]] [[sect]] and found in all [[sahaja]] schools. |

| + | |||

| + | Whether [[conceived]] of as '[[supreme bliss]]' ([[Mahā-sukha]]), as by the [[Buddhist]] [[Sahajiyās]], or as '[[supreme love]]' (as with the [[Vaiṣṇava]] [[Sahajiyās]]), strength of the [[body]] was deemed necessary to stand such a supreme realisation. | ||

| Line 44: | Line 46: | ||

| − | [[Sahaja]] is one of the four keywords of the [[Nath sampradaya]] along with Svecchachara, [[Sama]], and [[Samarasa]]. [[Sahaja]] [[meditation]] and {{Wiki|worship}} was prevalent in [[Tantric traditions]] common to [[Hinduism]] and [[Buddhism]] in {{Wiki|Bengal}} as early as the 8th–9th centuries. The [[British]] [[Nath]] [[teacher]] [[Mahendranath]] wrote: | + | [[Sahaja]] is one of the four keywords of the [[Nath sampradaya]] along with ]]Svecchachara\\, [[Sama]], and [[Samarasa]]. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Sahaja]] [[meditation]] and {{Wiki|worship}} was prevalent in [[Tantric traditions]] common to [[Hinduism]] and [[Buddhism]] in {{Wiki|Bengal}} as early as the 8th–9th centuries. The [[British]] [[Nath]] [[teacher]] [[Mahendranath]] wrote: | ||

| Line 53: | Line 57: | ||

It has no swadharma or {{Wiki|rules}}, duties and obligations incurred by [[birth]]. | It has no swadharma or {{Wiki|rules}}, duties and obligations incurred by [[birth]]. | ||

| − | It has only [[svabhava]] - its [[own]] inborn [[self]] or [[essence]] - to guide it. [[Sahaja]] is that [[nature]] which, when established in oneself, brings the [[state of absolute | + | It has only [[svabhava]] - its [[own]] inborn [[self]] or [[essence]] - to guide it. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Sahaja]] is that [[nature]] which, when established in oneself, brings the [[state of absolute freedom and peace]]. | ||

| Line 63: | Line 69: | ||

The [[Vaishnava-Sahajiya]] [[sect]] became popular in 17th century {{Wiki|Bengal}}. It sought [[religious experience]] through the [[five senses]]. | The [[Vaishnava-Sahajiya]] [[sect]] became popular in 17th century {{Wiki|Bengal}}. It sought [[religious experience]] through the [[five senses]]. | ||

| − | The [[divine]] relationship between [[Krishna]] and [[Radha]] (guises of the [[divine]] {{Wiki|masculine}} and [[divine]] {{Wiki|feminine}}) had been celebrated by [[Chandidas]] (Bangla: [[চন্ডীদাস]]) (born 1408 CE), [[Jayadeva]] (circa 1200 CE) and Vidyapati (c 1352 - c 1448) whose works foreshadowed the [[rasas]] or "flavours" of [[love]]. The two aspects of [[absolute reality]] were explained as the eternal enjoyer and the enjoyed, | + | The [[divine]] relationship between [[Krishna]] and [[Radha]] (guises of the [[divine]] {{Wiki|masculine}} and [[divine]] {{Wiki|feminine}}) had been celebrated by [[Chandidas]] (Bangla: [[চন্ডীদাস]]) (born 1408 CE), |

| + | |||

| + | [[Jayadeva]] (circa 1200 CE) and [[Vidyapati]] (c 1352 - c 1448) whose works foreshadowed the [[rasas]] or "flavours" of [[love]]. The two aspects of [[absolute reality]] were explained as the eternal enjoyer and the enjoyed, | ||

| + | |||

[[Kṛṣṇa]] and {{Wiki|Rādhā}} [[conceived]] of as [[Wikipedia:Ontology|ontological]] {{Wiki|principles}} of which all men and women are [[physical]] [[manifestations]], as may be realised through a process of attribution ([[Aropa]]), in which the {{Wiki|sexual}} intercourse of a [[human]] couple is transmuted into the [[divine]] [[love]] between [[Kṛṣṇa]] and {{Wiki|Rādhā}}, leading to the [[highest]] [[spiritual]] realisation, the [[state]] of union or Yugala. | [[Kṛṣṇa]] and {{Wiki|Rādhā}} [[conceived]] of as [[Wikipedia:Ontology|ontological]] {{Wiki|principles}} of which all men and women are [[physical]] [[manifestations]], as may be realised through a process of attribution ([[Aropa]]), in which the {{Wiki|sexual}} intercourse of a [[human]] couple is transmuted into the [[divine]] [[love]] between [[Kṛṣṇa]] and {{Wiki|Rādhā}}, leading to the [[highest]] [[spiritual]] realisation, the [[state]] of union or Yugala. | ||

| Line 80: | Line 89: | ||

| − | The [[sahaja-siddhi]] or the [[siddhi]] or " | + | The [[sahaja-siddhi]] or the [[siddhi]] or "[[natural accomplishment]]" or the "[[accomplishment of the unconditioned natural state]]" was also a textual work, the [[Sahaja-Siddhi]] revealed by [[Dombi Heruka]] (Skt. [[Ḍombi Heruka]] or [[Ḍombipa]]) one of the [[eighty-four Mahasiddhas]]. |

| + | |||

The following quotation identifies the relationship of the '[[mental]] flux' ([[mindstream]]) to the [[sahaja-siddhi]]. | The following quotation identifies the relationship of the '[[mental]] flux' ([[mindstream]]) to the [[sahaja-siddhi]]. | ||

| − | Moreover, it must be remembered that though Sundararajan & Mukerji (2003: p. 502) use a {{Wiki|masculine}} pronominal the term '[[siddha]]' is not gender-specific and that there were females, many as senior [[sadhakas]], amongst the [[siddha]] communities: | + | Moreover, it must be remembered that though [[Sundararajan]] & [[Mukerji]] (2003: p. 502) use a {{Wiki|masculine}} pronominal the term '[[siddha]]' is not gender-specific and that there were females, many as senior [[sadhakas]], amongst the [[siddha]] communities: |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * The [[practitioner]] is now a [[siddha]], a [[realized]] [[soul]]. He becomes invulnerable, beyond all dangers, when all [[forms]] melt away into the [[Formless]], "when [[surati]] merges in [[nirati]], [[japa]] is lost in [[ajapā]]" (Sākhī, "Parcā ko [[Aṅga]]," d.23). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The meeting of [[surati]] and [[nirati]] is one of the [[signs]] of [[sahaja-siddhi]]; [[surati]] is an act of will even when the [[practitioner]] struggles to disengage himself from [[worldly]] [[attachments]]. | ||

| − | + | But when his worldliness is totally destroyed with the dissolution of the [[ego]], there is [[nirati]], [[cessation]] of the [[mental]] flux, which implies [[cessation]] of all willed efforts. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Nirati]] ([[ni-rati]]) is also [[cessation]] of attractions, since the [[object]] of [[attraction]] and the seeker are now one. | |

| − | + | In terms of [[layayoga]], [[nirati]] is dissolution of the [[mind]] in "[[Sound]]," [[nāda]]. | |

| Line 101: | Line 116: | ||

| − | [[Ramana Maharshi]] {{Wiki|distinguished}} between [[kevala | + | [[Ramana Maharshi]]; {{Wiki|distinguished}} between [[kevala nirvikalpa samadhi]] and [[sahaja nirvikalpa samadhi]]: |

| − | * [[Sahaja | + | * [[Sahaja samadhi]]; is a [[state]] in which a [[silent]] level within the [[subject]] is maintained along with (simultaneously with) the full use of the [[human]] [[faculties]]. |

| − | [[Kevala | + | [[Kevala nirvikalpa samadhi]]; is temporary, whereas [[sahaja nirvikalpa samadhi]] is a continues [[state]] throughout daily [[activity]]. |

This [[state]] seems inherently more complex than [[samadhi]], since it involves several aspects of [[life]], namely external [[activity]], internal [[quietude]], and the [[relation]] between them. | This [[state]] seems inherently more complex than [[samadhi]], since it involves several aspects of [[life]], namely external [[activity]], internal [[quietude]], and the [[relation]] between them. | ||

Latest revision as of 21:54, 4 April 2016

Sahaja (Sanskrit; IAST: sahaja; Devanagari: सहज, meaning "spontaneous, natural, simple, or easy" is a term of some importance in Indian spirituality, particularly in circles influenced by the Tantric Movement. Ananda Coomaraswamy describes its significance as "the last achievement of all thought",

and "a recognition of the identity of spirit and matter, subject and object", continuing "There is then no sacred or profane, spiritual or sensual, but everything that lives is pure and void.

Sahaja (Sanskrit: सहज; Tibetan: lhan cig skyes pa), meaning "coemergent; spontaneously or naturally born together" is a term of some importance in Indian and Tibetan Buddhist spirituality, particularly in circles influenced by the tantra.

Ananda Coomaraswamy describes its significance as "the last achievement of all thought",

and "a recognition of the identity of spirit and matter, subject and object", continuing "There is then no sacred or profane, spiritual or sensual, but everything that lives is pure and void.

Origins

The origin of the word is Apabhraṃśa, where its first attested literary usage occurs in the 8th century CE. The word was used in a spiritual context by the Kamarupan siddha Saraha in the 8th century CE:

The Victorious Ones are filled with perfect [qualities],

Which all have the very same nature——spontaneous presence.

From [the natural display of the great sphere), living beings take birth and therein cease.

In relation to this, there is no thing and no nonthing.

The concept of a spontaneous spirituality entered Hinduism with Nath yogis such as Gorakshanath and was often alluded to indirectly and symbolically in the twilight language (sandhya bhasa) common to sahaja traditions as found in the Charyapada and works by Matsyendranath and Daripada.

It influenced the bhakti movement through the Sant tradition, exemplified by the Bauls of Bengal, Dnyaneshwar, Meera, Kabir and Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism.

Yoga in particular had a quickening influence on the various ]]Sahajiya\\ traditions. The culture of the body (]]kāya-sādhana\\) through processes of Haṭha-yoga was of paramount importance in the Nāth sect and found in all sahaja schools.

Whether conceived of as 'supreme bliss' (Mahā-sukha), as by the Buddhist Sahajiyās, or as 'supreme love' (as with the Vaiṣṇava Sahajiyās), strength of the body was deemed necessary to stand such a supreme realisation.

Sahaja is one of the four keywords of the Nath sampradaya along with ]]Svecchachara\\, Sama, and Samarasa.

Sahaja meditation and worship was prevalent in Tantric traditions common to Hinduism and Buddhism in Bengal as early as the 8th–9th centuries. The British Nath teacher Mahendranath wrote:

- Man is born with an instinct for naturalness. He has never forgotten the days of his primordial perfection, except insomuch as the memory became buried under the artificial superstructure of civilization and its artificial concepts. Sahaja means natural...

The tree grows according to Sahaja, natural and spontaneous in complete conformity with the Natural Law of the Universe. Nobody tells it what to do or how to grow.

It has no swadharma or rules, duties and obligations incurred by birth.

It has only svabhava - its own inborn self or essence - to guide it.

Sahaja is that nature which, when established in oneself, brings the state of absolute freedom and peace.

The Vaishnava-Sahajiya sect became popular in 17th century Bengal. It sought religious experience through the five senses.

The divine relationship between Krishna and Radha (guises of the divine masculine and divine feminine) had been celebrated by Chandidas (Bangla: চন্ডীদাস) (born 1408 CE),

Jayadeva (circa 1200 CE) and Vidyapati (c 1352 - c 1448) whose works foreshadowed the rasas or "flavours" of love. The two aspects of absolute reality were explained as the eternal enjoyer and the enjoyed,

Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā conceived of as ontological principles of which all men and women are physical manifestations, as may be realised through a process of attribution (Aropa), in which the sexual intercourse of a human couple is transmuted into the divine love between Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā, leading to the highest spiritual realisation, the state of union or Yugala.

The element of love, the innovation of the Vaiṣṇava Sahajiyā school, is essentially based on the element of yoga in the form of physical and psychological discipline.

Vaisnava-Sahajiya is a synthesis and complex of traditions that, due to its sexual tantric practices, was perceived with disdain by other religious communities and much of the time was forced to operate in secrecy.

Its literature employed an encrypted and enigmatic style. Because of the necessity of privacy and secrecy, little is definitively known about their prevalence or practices.

The sahaja-siddhi or the siddhi or "natural accomplishment" or the "accomplishment of the unconditioned natural state" was also a textual work, the Sahaja-Siddhi revealed by Dombi Heruka (Skt. Ḍombi Heruka or Ḍombipa) one of the eighty-four Mahasiddhas.

The following quotation identifies the relationship of the 'mental flux' (mindstream) to the sahaja-siddhi.

Moreover, it must be remembered that though Sundararajan & Mukerji (2003: p. 502) use a masculine pronominal the term 'siddha' is not gender-specific and that there were females, many as senior sadhakas, amongst the siddha communities:

- The practitioner is now a siddha, a realized soul. He becomes invulnerable, beyond all dangers, when all forms melt away into the Formless, "when surati merges in nirati, japa is lost in ajapā" (Sākhī, "Parcā ko Aṅga," d.23).

The meeting of surati and nirati is one of the signs of sahaja-siddhi; surati is an act of will even when the practitioner struggles to disengage himself from worldly attachments.

But when his worldliness is totally destroyed with the dissolution of the ego, there is nirati, cessation of the mental flux, which implies cessation of all willed efforts.

Nirati (ni-rati) is also cessation of attractions, since the object of attraction and the seeker are now one.

In terms of layayoga, nirati is dissolution of the mind in "Sound," nāda.

Ramana Maharshi; distinguished between kevala nirvikalpa samadhi and sahaja nirvikalpa samadhi:

- Sahaja samadhi; is a state in which a silent level within the subject is maintained along with (simultaneously with) the full use of the human faculties.

Kevala nirvikalpa samadhi; is temporary, whereas sahaja nirvikalpa samadhi is a continues state throughout daily activity.

This state seems inherently more complex than samadhi, since it involves several aspects of life, namely external activity, internal quietude, and the relation between them.

It also seems to be a more advanced state, since it comes after the mastering of samadhi.