Difference between revisions of "A Short History of Buddhism in Australia"

| (11 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | This article was first published in the Vietnamese Buddhist journal Giac Ngo (in a translation into Vietnamese by the Ven. Thich Nguyen Tang and later this was published by Kerry Trembath, Sydney, November 1996). | + | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | This article was first published in the [[Vietnamese]] [[Buddhist]] journal Giac Ngo (in a translation into [[Vietnamese]] by the Ven. Thich [[Nguyen]] Tang and later this was published by Kerry Trembath, {{Wiki|Sydney}}, November 1996). | ||

=== First contacts with [[Buddhism]] === | === First contacts with [[Buddhism]] === | ||

[[File:024 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:024 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | It is not known precisely when [[Buddhism]] first came to Australia. Professor A.P. Elkin has argued that there may have been contact between the Aboriginal people of northern Australia and the early Hindu-Buddhist civilisations of Indonesia. He suggests that Aboriginal practices of mind training and belief in [[Reincarnation]] may be evidence of such contact. It is also possible that the great fleets of the Chinese Ming emperors which explored the south between 1405 and 1433 may have reached the mainland of Australia. | + | It is not known precisely when [[Buddhism]] first came to [[Australia]]. {{Wiki|Professor}} A.P. Elkin has argued that there may have been [[contact]] between the Aboriginal [[people]] of northern [[Australia]] and the early Hindu-Buddhist civilisations of {{Wiki|Indonesia}}. He suggests that Aboriginal practices of [[mind training]] and [[belief]] in [[Reincarnation]] may be {{Wiki|evidence}} of such [[contact]]. It is also possible that the great fleets of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Ming]] [[emperors]] which explored the {{Wiki|south}} between 1405 and 1433 may have reached the mainland of [[Australia]]. |

| − | The first certain contact with [[Buddhism]] can be dated to 1848, when Chinese labourers arrived to work on the goldfields of eastern Australia. The beliefs of these men were predominantly Taoist/Confucian, but the makeshift temples they built have been found to contain remnants of [[Mahayana]] Buddhist statues. Most of these men returned to China when the goldrush ended, but some stayed in Australia, often after sending for a wife from China. While the older Chinese continued to practice their ancestral beliefs, their children and grandchildren often adopted the Christian [[Faith]]. | + | The first certain [[contact]] with [[Buddhism]] can be dated to 1848, when {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|labourers}} arrived to work on the goldfields of eastern [[Australia]]. The [[beliefs]] of these men were predominantly Taoist/Confucian, but the makeshift [[temples]] they built have been found to contain remnants of [[Mahayana]] [[Buddhist]] [[statues]]. Most of these men returned to [[China]] when the goldrush ended, but some stayed in [[Australia]], often after sending for a wife from [[China]]. While the older {{Wiki|Chinese}} continued to practice their ancestral [[beliefs]], their children and grandchildren often adopted the {{Wiki|Christian}} [[Faith]]. |

| − | In the 1870s, groups of Sinhalese from Sri Lanka began to arrive in Australia to work on the sugar plantations of northern Queensland, or in the pearling industry centred on Thursday Island. By the 1890s, the Buddhist population of Thursday Island included about 500 Sinhalese people. Two [[Bodhi]] trees planted by this community are still growing on Thursday Island to this day. A temple was built on Thursday Island, festivals such as Vesak were regularly celebrated, and a [[Buddhist monk]] is said to have visited to officiate at the temple around the turn of the century. | + | In the 1870s, groups of {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} from [[Sri Lanka]] began to arrive in [[Australia]] to work on the sugar plantations of northern [[Queensland]], or in the pearling industry centred on Thursday [[Island]]. By the 1890s, the [[Buddhist]] population of Thursday [[Island]] included about 500 {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} [[people]]. Two [[Bodhi]] [[trees]] planted by this {{Wiki|community}} are still growing on Thursday [[Island]] to this day. A [[temple]] was built on Thursday [[Island]], {{Wiki|festivals}} such as [[Vesak]] were regularly celebrated, and a [[Buddhist monk]] is said to have visited to officiate at the [[temple]] around the turn of the century. |

| − | Soon after Federation in 1901, Australia adopted increasingly restrictive immigration policies which effectively halted further Asian immigration until the 1960s. | + | Soon after Federation in 1901, [[Australia]] adopted increasingly restrictive immigration policies which effectively halted further {{Wiki|Asian}} immigration until the 1960s. |

| − | === Early Western Buddhists in Australia === | + | === Early [[Western]] [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]] === |

[[File:Av1qz.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Av1qz.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | By the late 1800s, increasing numbers of Westerners were becoming interested in Asian culture and religion. In 1891, Colonel Henry Steel Olcott spent several months lecturing throughout Australia on `Theosophy and [[Buddhism]]'. Olcott was the co-founder of the Theosophical Society who described himself as a Buddhist, having taken the [[ | + | By the late 1800s, {{Wiki|increasing}} numbers of [[Westerners]] were becoming [[interested]] in {{Wiki|Asian}} {{Wiki|culture}} and [[religion]]. In 1891, Colonel {{Wiki|Henry Steel Olcott}} spent several months lecturing throughout [[Australia]] on `[[Theosophy]] and [[Buddhism]]'. [[Olcott]] was the co-founder of the {{Wiki|Theosophical Society}} who described himself as a [[Buddhist]], having taken the [[three refuges]] and The [[Five Precepts]] in [[Sri Lanka]] in 1880. His lectures in [[Australia]] were well attended and well received. Small but significant numbers of generally well-educated and influential [[Australians]] joined the {{Wiki|Theosophical Society}}, the [[aim]] of which, according to [[Olcott]], was to disseminate [[Buddhist Philosophy]]. One of those who joined the {{Wiki|Theosophical Society}} at this [[time]] was Alfred Deakin, who was later to be three times [[Prime Minister]] of [[Australia]]. Deakin retained a [[lifetime]] [[Interest]] in and regard for [[Buddhism]] and even wrote a [[book]] about a visit to [[India]] and [[Sri Lanka]] which included three chapters which were highly sympathetic to [[Buddhism]]. |

| − | In time, the Theosophical Society drifted away from its strong focus on [[Buddhism]], becoming more eclectic and giving greater emphasis to spiritualism and occultism. Nevertheless, the importance of the Theosophical Society in the early history of [[Buddhism]] in Australia cannot be overlooked. To this day, the Society's bookshop in Sydney, Adyar, remains one of the best sources of Buddhist literature in the country. | + | In [[time]], the {{Wiki|Theosophical Society}} drifted away from its strong focus on [[Buddhism]], becoming more eclectic and giving [[greater]] {{Wiki|emphasis}} to [[spiritualism]] and [[occultism]]. Nevertheless, the importance of the {{Wiki|Theosophical Society}} in the early {{Wiki|history}} of [[Buddhism]] in [[Australia]] cannot be overlooked. To this day, the Society's bookshop in {{Wiki|Sydney}}, [[Adyar]], {{Wiki|remains}} one of the best sources of [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|literature}} in the country. |

| − | Another important figure in the Theosophical Society made a contribution to [[The History of Buddhism]] in Australia. In 1919, F.L. Woodward, who for 16 years had been principal of Mahinda College in Galle, Sri Lanka, arrived in Australia. He settled on an apple orchard near Launceston in Tasmania, and for the next 33 years devoted his time to translations of the [[Pali]] Canon for the [[Pali]] Text Society. He is perhaps best known for his anthology, Some Sayings of [[ | + | Another important figure in the {{Wiki|Theosophical Society}} made a contribution to [[The History of Buddhism]] in [[Australia]]. In 1919, F.L. Woodward, who for 16 years had been [[principal]] of [[Mahinda]] {{Wiki|College}} in {{Wiki|Galle}}, [[Sri Lanka]], arrived in [[Australia]]. He settled on an apple orchard near Launceston in {{Wiki|Tasmania}}, and for the next 33 years devoted his [[time]] to translations of the [[Pali]] [[Canon]] for the [[Pali]] Text {{Wiki|Society}}. He is perhaps best known for his {{Wiki|anthology}}, Some Sayings of The [[Buddha]], first published in 1925. This popular [[book]] provided an introduction to [[Buddhism]] for many [[Westerners]], [[including]] some who later became prominent [[Australian]] [[Buddhists]]. |

| − | The earliest group of Western Buddhists in Australia, The Little Circle of [[ | + | The earliest group of [[Western]] [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]], The Little Circle of the [[Dharma]], may have been formed in 1925 in {{Wiki|Melbourne}} by Max Tyler, Max Dunn and David Maurice. This group was strongly influenced by the [[Theravada]] [[tradition]] of [[Burma]]. By the 1950s, David Maurice was editing The [[Light]] of the [[Dhamma]], a [[Buddhist]] magazine in {{Wiki|English}} which had a wide circulation throughout the [[world]], and in 1962 he published The [[Lion's Roar]], his {{Wiki|anthology}} of the [[Pali]] [[Canon]]. Another early group was established in {{Wiki|Melbourne}} in 1938 by Leonard Bullen, and was called The [[Buddhist]] Study Group. Unfortunately, the outbreak of the second [[World]] [[War]] in 1939 put a stop to this [[promising]] start. |

| − | Women played an important part in the development of [[Buddhism]] in Australia. Marie Byles, the first woman solicitor in the country and also a prominent conservationist, feminist and pacifist, wrote many [[Books]] and articles on [[Buddhism]] in the 1940s and 1950s. Only one of her [[Books]], Footprints of Gautama [[ | + | Women played an important part in the [[development]] of [[Buddhism]] in [[Australia]]. Marie Byles, the first woman solicitor in the country and also a prominent conservationist, feminist and pacifist, wrote many [[Books]] and articles on [[Buddhism]] in the 1940s and 1950s. Only one of her [[Books]], Footprints of [[Gautama]] The [[Buddha]], is still in print. She gave many talks in {{Wiki|Sydney}} as well as broadcasting on the {{Wiki|Theosophical}} Society's regular [[Sunday]] night radio program on Radio Station 2GB. Marie Byles studied [[Vipassana]] [[Meditation]] in [[Burma]], and built a [[Meditation]] hut in the [[garden]] of her {{Wiki|Sydney}} home which is still there to this day. Her home and [[garden]] have been given to the [[people]] of {{Wiki|Sydney}} as a quiet [[Retreat]]. Her extensive library of [[Buddhist]] [[Books]], [[including]] a full set of the [[Tripitika]] in {{Wiki|English}}, was bequeathed to the library of the {{Wiki|University}} of {{Wiki|Sydney}}. |

| − | In 1952, the first [[Buddhist nun]] visited Australia. Sister Dhammadina, born in the USA and with thirty years experience in Sri Lanka, was sponsored by Dr Malasekera, the first president of the World Fellowship of Buddhists. Although she was already 70 years old, Sister Dhammadina was enterprising and energetic, and her 11 months in Sydney helped to further the growing [[Interest]] in [[Buddhism]]. | + | In 1952, the first [[Buddhist nun]] visited [[Australia]]. Sister Dhammadina, born in the {{Wiki|USA}} and with thirty years [[experience]] in [[Sri Lanka]], was sponsored by Dr Malasekera, the first [[president]] of the {{Wiki|World Fellowship of Buddhists}}. Although she was already 70 years old, Sister Dhammadina was enterprising and energetic, and her 11 months in {{Wiki|Sydney}} helped to further the growing [[Interest]] in [[Buddhism]]. |

| − | === The first Buddhist societies in Australia === | + | === The first [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|societies}} in [[Australia]] === |

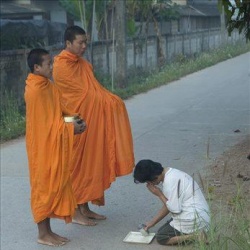

[[File:Alms thai.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Alms thai.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Around this time, the Buddhist Society of New South Wales, Australia's oldest surviving Buddhist society, was established by Leo Berkeley, a Sydney businessman. A leading member of this group was Natasha Jackson, who edited the publication [[Metta]] from 1955 (originally Buddhist News, edited by Gordon Lishman) and who exerted a powerful influence on the development of Australian [[Buddhism]] over the next 20 years. In 1953, the Buddhist Society of Victoria and the Buddhist Society of Queensland were established. Until the 1960s, the focus in Sydney was strongly [[Theravadin]] while in Melbourne it was more eclectic with both [[Theravadin]] and Japanese [[Zen]] influences. In 1973, the Buddhist Society of Western Australia was formed in Perth. This society was also primarily [[Theravadin]]. | + | Around this [[time]], the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}} of New {{Wiki|South}} [[Wales]], Australia's oldest surviving [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|society}}, was established by Leo {{Wiki|Berkeley}}, a {{Wiki|Sydney}} businessman. A leading member of this group was Natasha Jackson, who edited the publication [[Metta]] from 1955 (originally [[Buddhist]] News, edited by Gordon Lishman) and who exerted a {{Wiki|powerful}} [[influence]] on the [[development]] of [[Australian]] [[Buddhism]] over the next 20 years. In 1953, the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}} of Victoria and the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}} of [[Queensland]] were established. Until the 1960s, the focus in {{Wiki|Sydney}} was strongly [[Theravadin]] while in {{Wiki|Melbourne}} it was more eclectic with both [[Theravadin]] and [[Japanese]] [[Zen]] [[influences]]. In 1973, the [[Buddhist Society of Western Australia]] was formed in {{Wiki|Perth}}. This {{Wiki|society}} was also primarily [[Theravadin]]. |

| − | In 1958, the Sydney-based Buddhist Federation of Australia was formed with Charles Knight as its chairperson and Natasha Jackson as a central figure. The Federation took over publication of [[Metta]], later renaming it [[Buddhism]] Today. This journal is still published to this day, making it the oldest continuing Buddhist publication in Australia. | + | In 1958, the Sydney-based [[Buddhist]] Federation of [[Australia]] was formed with Charles Knight as its chairperson and Natasha Jackson as a {{Wiki|central}} figure. The Federation took over publication of [[Metta]], later renaming it [[Buddhism]] Today. This journal is still published to this day, making it the oldest continuing [[Buddhist]] publication in [[Australia]]. |

| − | The Chinese Buddhist Society of Australia was established in Sydney in 1972 by businessman Eric Liao, who had arrived in Australia in 1961. | + | The {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}} of [[Australia]] was established in {{Wiki|Sydney}} in 1972 by businessman Eric Liao, who had arrived in [[Australia]] in 1961. |

| − | === Visits to Australia by Sangha from overseas === | + | === Visits to [[Australia]] by [[Sangha]] from overseas === |

| − | In 1954, [[Venerable]] U Thittila came to Australia from Burma in the first of his three trips to give talks and guidance to the newly formed Buddhist societies. [[Venerable]] Narada [[Thera]] came a year later from Sri Lanka at the invitation of the Buddhist Society of Queensland. Sister Dhammadina returned to Australia in 1957. These visits received extensive publicity, and during this time the membership of the Buddhist societies doubled to around 100 in Sydney and 40 in Melbourne. As in the past, the majority of those drawn to [[Buddhism]] were well educated, in professional or managerial occupations, or in the arts and literature. | + | In 1954, [[Venerable]] U [[Thittila]] came to [[Australia]] from [[Burma]] in the first of his three trips to give talks and guidance to the newly formed [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|societies}}. [[Venerable]] [[Narada]] [[Thera]] came a year later from [[Sri Lanka]] at the invitation of the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}} of [[Queensland]]. Sister Dhammadina returned to [[Australia]] in 1957. These visits received extensive publicity, and during this [[time]] the membership of the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|societies}} doubled to around 100 in {{Wiki|Sydney}} and 40 in {{Wiki|Melbourne}}. As in the {{Wiki|past}}, the majority of those drawn to [[Buddhism]] were well educated, in professional or managerial occupations, or in the [[arts]] and {{Wiki|literature}}. |

| − | During the 1960s, notable visitors included the abbot of Higashi Hongan-ji temple in Kyoto; the [[Venerable]] Piyadassi [[Thera]] from Sri Lanka; the famous Vietnamese teacher and writer, the [[Venerable]] Thich Nhat Hanh; and the [[Venerable]] Phra Sasanasobhon, chair of the Mahamakut Educational Foundation of Thailand. | + | During the 1960s, notable visitors included the [[abbot]] of [[Higashi Hongan-ji]] [[temple]] in {{Wiki|Kyoto}}; the [[Venerable]] [[Piyadassi]] [[Thera]] from [[Sri Lanka]]; the famous [[Vietnamese]] [[teacher]] and writer, the [[Venerable]] [[Thich Nhat Hanh]]; and the [[Venerable]] [[Phra]] Sasanasobhon, chair of the Mahamakut Educational Foundation of [[Thailand]]. |

| − | === The establishment of Mahayana in Australia === | + | === The establishment of [[Mahayana]] in [[Australia]] === |

| − | A master of the Chinese [[Zen]] tradition arrived in Sydney from Hong Kong in 1961. He was [[Hsuan Hua]], also known as An-tz'u and To-lun. [[Language]] difficulties and the strong [[Theravada]] orientation of Western Buddhists in Sydney limited his impact and he left in 1961 to go to California where he later founded the monastic complex, `City of the Ten Thousand [[Buddhas]]'. The Soto [[Zen]] Buddhist Society was formed in Sydney in 1961, and the Sydney [[Zen]] Centre was established in 1976. This centre was associated with the Soto [[Zen]] Diamond [[Sangha]] in Hawaii. Robert Aitken [[Roshi]], the director of the Hawaiian centre, visited annually in the early years, and his Australian-born disciple, John Tarrant [[Roshi]] (now living in California) has continued his work. During the 1970s and 1980s, small groups dedicated to the practice of [[Zen]] were formed in Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth. | + | A [[master]] of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Zen]] [[tradition]] arrived in {{Wiki|Sydney}} from {{Wiki|Hong Kong}} in 1961. He was [[Hsuan Hua]], also known as An-tz'u and To-lun. [[Language]] difficulties and the strong [[Theravada]] orientation of [[Western]] [[Buddhists]] in {{Wiki|Sydney}} limited his impact and he left in 1961 to go to [[California]] where he later founded the [[monastic]] complex, `City of the Ten Thousand [[Buddhas]]'. The [[Soto]] [[Zen]] [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}} was formed in {{Wiki|Sydney}} in 1961, and the {{Wiki|Sydney}} [[Zen]] Centre was established in 1976. This centre was associated with the [[Soto]] [[Zen]] [[Diamond]] [[Sangha]] in [[Hawaii]]. {{Wiki|Robert Aitken}} [[Roshi]], the director of the Hawaiian centre, visited annually in the early years, and his Australian-born [[disciple]], John Tarrant [[Roshi]] (now living in [[California]]) has continued his work. During the 1970s and 1980s, small groups dedicated to the practice of [[Zen]] were formed in [[Brisbane]], {{Wiki|Melbourne}}, Adelaide and {{Wiki|Perth}}. |

| − | === The first monasteries in Australia === | + | === The first [[monasteries]] in [[Australia]] === |

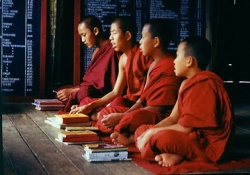

[[File:131.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:131.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | During the 1970s, there was a strong growth of [[Interest]] in [[Buddhism]], especially among young people. During this period, it has been estimated that close to 300 Australians attended the annual retreats in northern [[India]] and Nepal conducted by Tibetan teachers such as [[Lama]] [[Thubten Yeshe]] and [[Lama]] Thubten Zopa. In Thailand, perhaps as many as 200 Australians may have been ordained as monks for various periods of time in Thailand. By this time also, large numbers of immigrants and refugees from Asia were coming to Australia to settle, and many of these were Buddhists. The time was ripe for establishment of the first Buddhist monasteries in Australia. | + | During the 1970s, there was a strong growth of [[Interest]] in [[Buddhism]], especially among young [[people]]. During this period, it has been estimated that close to 300 [[Australians]] attended the annual [[retreats]] in northern [[India]] and [[Nepal]] conducted by [[Tibetan]] [[teachers]] such as [[Lama]] [[Thubten Yeshe]] and [[Lama]] [[Thubten Zopa]]. In [[Thailand]], perhaps as many as 200 [[Australians]] may have been [[ordained]] as [[monks]] for various periods of [[time]] in [[Thailand]]. By this [[time]] also, large numbers of immigrants and refugees from {{Wiki|Asia}} were coming to [[Australia]] to settle, and many of these were [[Buddhists]]. The [[time]] was ripe for establishment of the first [[Buddhist]] [[monasteries]] in [[Australia]]. |

| − | The [[Venerable]] Somaloka, a young Sri Lankan [[Monk]], arrived in Sydney in 1971, initially at the invitation of the Buddhist Society of New South Wales. On Vesak Day, 1973, the Australian Buddhist [[Vihara]] was opened at Katoomba in the Blue Mountains, a short distance to the west of Sydney. This was the first monastery in Australia. [[Venerable]] Somaloka still resides there, but the temple has never been attended by large numbers of Buddhists and its influence on the growth of [[Buddhism]] in Australia has been limited. | + | The [[Venerable]] Somaloka, a young [[Sri Lankan]] [[Monk]], arrived in {{Wiki|Sydney}} in 1971, initially at the invitation of the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}} of New {{Wiki|South}} [[Wales]]. On [[Vesak]] Day, 1973, the [[Australian]] [[Buddhist]] [[Vihara]] was opened at Katoomba in the Blue [[Mountains]], a short distance to the {{Wiki|west}} of {{Wiki|Sydney}}. This was the first [[monastery]] in [[Australia]]. [[Venerable]] Somaloka still resides there, but the [[temple]] has never been attended by large numbers of [[Buddhists]] and its [[influence]] on the growth of [[Buddhism]] in [[Australia]] has been limited. |

| − | In 1973, [[Venerable]] Phra Khantipalo, an English-born [[Monk]] from Wat Bovoranives in Thailand, arrived in Sydney. Shortly later, he was followed by Phra Chao Khun Pariyattikavee from the Mahamakut Foundation in Thailand. Phra Khantipalo spent the next 2 years teaching throughout Australia. On Vesak Day, 1995, Wat Buddharangsee (`monastery of [[ | + | In 1973, [[Venerable]] [[Phra]] [[Khantipalo]], an English-born [[Monk]] from [[Wat Bovoranives]] in [[Thailand]], arrived in {{Wiki|Sydney}}. Shortly later, he was followed by [[Phra]] [[Chao Khun]] Pariyattikavee from the Mahamakut Foundation in [[Thailand]]. [[Phra]] [[Khantipalo]] spent the next 2 years [[teaching]] throughout [[Australia]]. On [[Vesak]] Day, 1995, [[Wat Buddharangsee]] (`[[monastery]] of The [[Buddha]]'s radiance') was opened at Stanmore in {{Wiki|Sydney}} by the {{Wiki|Crown}} {{Wiki|Prince}} of [[Thailand]] in the presence of [[Phra]] [[Khantipalo]] and his [[teacher]], [[Somdet Phra]] Nyanasamsvara, and 7 other visiting [[abbots]]. Under the [[leadership]] of its [[abbot]] [[Phra]] Mahasamai, this [[temple]] served not only the [[Thai]] {{Wiki|community}} in {{Wiki|Sydney}}, but also Laotian, [[Cambodian]], [[Burmese]], Malaysian, and even [[Vietnamese]] and {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhists]] before these groups were in a position to set up their [[own]] [[temples]]. [[Phra]] Mahasamai, now {{Wiki|Tan Chao Khun}} Samai, still works tirelessly for the betterment of the whole [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|community}} in {{Wiki|Sydney}}. |

| − | In 1978, Phra Khantipalo and the German-born nun [[Ayya]] Khema established Wat [[Buddha]] [[Dhamma]] in a bushland setting at Wiseman's Ferry north of Sydney. This functioned mainly as a centre for [[Meditation]] and retreats, and appealed to many Westerners who were attracted to [[Buddhism]]. | + | In 1978, [[Phra]] [[Khantipalo]] and the German-born [[nun]] [[Ayya]] [[Khema]] established Wat [[Buddha]] [[Dhamma]] in a bushland setting at Wiseman's Ferry {{Wiki|north}} of {{Wiki|Sydney}}. This functioned mainly as a centre for [[Meditation]] and [[retreats]], and appealed to many [[Westerners]] who were attracted to [[Buddhism]]. |

| − | Soon, other ethnic groups (Cambodian, Laotian, Burmese, Sri Lankans and Vietnamese) were establishing temples, mainly in Sydney and Melbourne where these groups had settled in largest numbers. A Chinese temple was established in Sydney's Chinatown district in 1972. This was followed by the Hwa Tsang Monastery at Homebush, where the first and still current abbot was the [[Venerable]] Tsang Hui. | + | Soon, other {{Wiki|ethnic}} groups ([[Cambodian]], Laotian, [[Burmese]], {{Wiki|Sri}} Lankans and [[Vietnamese]]) were establishing [[temples]], mainly in {{Wiki|Sydney}} and {{Wiki|Melbourne}} where these groups had settled in largest numbers. A {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[temple]] was established in Sydney's [[Chinatown]] district in 1972. This was followed by the Hwa {{Wiki|Tsang}} [[Monastery]] at Homebush, where the first and still current [[abbot]] was the [[Venerable]] {{Wiki|Tsang}} [[Hui]]. |

| − | === Vietnamese Buddhist organisations in Australia === | + | === [[Vietnamese]] [[Buddhist]] organisations in [[Australia]] === |

| − | Vietnamese Buddhist temples began to be established in the 1980s. In 1981, the senior Vietnamese [[Buddhist monk]], the Most [[Venerable]] Thich Phuoc Hue, arrived in Australia to form the Vietnamese Buddhist Federation of Australia. This organisation, now known as the United Vietnamese Congregations of Australia, has branch temples in all Australian states except Tasmania. Other prominent Vietnamese groups are the Vietnamese Buddhist Society of New South Wales ([[Venerable]] Thich Bao Lac), the [[Lotus]] Buds [[Sangha]] (followers of [[Venerable]] Thich Nhat Hanh), Linn Son (with headquarters in France and centres in Queensland and Victoria) and the [[Middle Way]] ([[Venerable]] Thich Minh Thien of [[ | + | [[Vietnamese]] [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] began to be established in the 1980s. In 1981, the {{Wiki|senior}} [[Vietnamese]] [[Buddhist monk]], the Most [[Venerable]] Thich Phuoc Hue, arrived in [[Australia]] to [[form]] the [[Vietnamese]] [[Buddhist]] Federation of [[Australia]]. This organisation, now known as the United [[Vietnamese]] Congregations of [[Australia]], has branch [[temples]] in all [[Australian]] states except {{Wiki|Tasmania}}. Other prominent [[Vietnamese]] groups are the [[Vietnamese]] [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}} of New {{Wiki|South}} [[Wales]] ([[Venerable]] Thich Bao Lac), the [[Lotus]] Buds [[Sangha]] (followers of [[Venerable]] [[Thich Nhat Hanh]]), Linn Son (with headquarters in {{Wiki|France}} and centres in [[Queensland]] and Victoria) and the [[Middle Way]] ([[Venerable]] Thich Minh [[Thien]] of The [[Buddha]] [[Relics]] [[Vihara]] in {{Wiki|Sydney}}).. Their [[temples]] usually follow [[Mahayana]] [[traditions]], especially [[Pure land]] and [[Ch'an]], and the [[Bodhisattva]] [[Kuan yin]] is frequently venerated. Many [[temples]] also have youth groups and offer part-time classes in [[Vietnamese]] [[Language]] and customs to help young [[people]] born in [[Australia]] to maintain their {{Wiki|culture}}. |

| − | === Tibetan Buddhism in Australia === | + | === [[Tibetan Buddhism]] in [[Australia]] === |

[[File:Bud4.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bud4.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Although the number of Tibetans in Australia is relatively small, the [[Vajrayana]] tradition is very attractive to many Westerners and the Tibetan influence in Australian [[Buddhism]] is strong. For example, nearly one third of all Buddhist organisations in Sydney is Tibetan. The [[Dalai Lama]] has visited Australia three times (1982, 1992 and 1996) and on each occasion he has drawn huge crowds of the general public as well as giving great [[Joy]] and inspiration to Buddhists of all traditions. | + | Although the number of [[Tibetans]] in [[Australia]] is relatively small, the [[Vajrayana]] [[tradition]] is very attractive to many [[Westerners]] and the [[Tibetan]] [[influence]] in [[Australian]] [[Buddhism]] is strong. For example, nearly one third of all [[Buddhist]] organisations in {{Wiki|Sydney}} is [[Tibetan]]. The [[Dalai Lama]] has visited [[Australia]] three times (1982, 1992 and 1996) and on each occasion he has drawn huge crowds of the general public as well as giving great [[Joy]] and inspiration to [[Buddhists]] of all [[traditions]]. |

| − | === Numbers of Buddhists in Australia === | + | === Numbers of [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]] === |

| − | Although many Australians are interested in [[Buddhism]], the number of Westerners who identify themselves as Buddhists is still very small. Most Buddhists in Australia are immigrants from Asia. | + | Although many [[Australians]] are [[interested]] in [[Buddhism]], the number of [[Westerners]] who identify themselves as [[Buddhists]] is still very small. Most [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]] are immigrants from {{Wiki|Asia}}. |

| − | From Table 1, which has been taken from figures published by the Australian government from the 1991 Census, it can be seen that people of Vietnamese origin are the largest single ethnic group of Buddhists, and that they make up nearly one third of all Australian Buddhists. Not all people born in Viet Nam were Buddhist - 35% of them identified as Catholic, and 60% as Buddhist. | + | From Table 1, which has been taken from figures published by the [[Australian]] government from the 1991 Census, it can be seen that [[people]] of [[Vietnamese]] origin are the largest single {{Wiki|ethnic}} group of [[Buddhists]], and that they make up nearly one third of all [[Australian]] [[Buddhists]]. Not all [[people]] born in [[Viet Nam]] were [[Buddhist]] - 35% of them identified as {{Wiki|Catholic}}, and 60% as [[Buddhist]]. |

| − | Less than a quarter of all Australian Buddhists were born in Australia, and of those, only one quarter had both parents born in Australia. | + | Less than a quarter of all [[Australian]] [[Buddhists]] were born in [[Australia]], and of those, only one quarter had both [[parents]] born in [[Australia]]. |

| − | Chinese Buddhists came from many countries, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia as well as the People's Republic of China. | + | {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhists]] came from many countries, such as {{Wiki|Taiwan}}, {{Wiki|Hong Kong}}, {{Wiki|Singapore}} and {{Wiki|Malaysia}} as well as the {{Wiki|People's Republic of China}}. |

| − | === Growth in Buddhism in Australia=== | + | === Growth in [[Buddhism]] in [[Australia]]=== |

| − | Numbers grew rapidly between 1981 and 1991, increasing by almost 300%. Buddhists have become Australia's fastest growing religious group, but they are still less than one percent of the Australian population (Table 2). | + | Numbers grew rapidly between 1981 and 1991, {{Wiki|increasing}} by almost 300%. [[Buddhists]] have become Australia's fastest growing [[religious]] group, but they are still less than one percent of the [[Australian]] population (Table 2). |

| − | Table 2: Buddhists by State and Territory,and as percentage of Australian population, 1891-1991 | + | Table 2: [[Buddhists]] by [[State]] and Territory,and as percentage of [[Australian]] population, 1891-1991 |

| − | Source: Australian Census figures, reported in Adam and Hughes, The Buddhists in Australia, Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, Australian Government Publishing Service, 1996. | + | Source: [[Australian]] Census figures, reported in Adam and Hughes, The [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]], Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, [[Australian]] Government Publishing Service, 1996. |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | Year NSW Vic Qld SA WA Tas NT ACT Total % | + | Year {{Wiki|NSW}} Vic Qld SA WA Tas NT ACT Total % |

1891 10,120 6,746 - 3,936 1,089 826 - - 22,717 1.2 | 1891 10,120 6,746 - 3,936 1,089 826 - - 22,717 1.2 | ||

| Line 101: | Line 113: | ||

1991 58,735 42,349 11,638 8,529 13,499 713 1,370 2,962 139,795 0.8 | 1991 58,735 42,349 11,638 8,529 13,499 713 1,370 2,962 139,795 0.8 | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| − | === Geographical spread of Buddhists in Australia === | + | === Geographical spread of [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]] === |

[[File:304.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:304.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The geographical distribution of Buddhists in Australia reflects the destinations of recent immigrants. Almost all settled in the capital cities, and most (around 79%) settled in Sydney and Melbourne (Table 3). Although the percentage of Buddhists in Australia is only around 0.8%, they form a more significant proportion of the population in Sydney, Melbourne and Darwin. | + | The geographical distribution of [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]] reflects the destinations of recent immigrants. Almost all settled in the {{Wiki|capital}} cities, and most (around 79%) settled in {{Wiki|Sydney}} and {{Wiki|Melbourne}} (Table 3). Although the percentage of [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]] is only around 0.8%, they [[form]] a more significant proportion of the population in {{Wiki|Sydney}}, {{Wiki|Melbourne}} and {{Wiki|Darwin}}. |

| − | Table 3: Buddhists living in the capital cities of Australia | + | Table 3: [[Buddhists]] living in the {{Wiki|capital}} cities of [[Australia]] |

| − | Source: 1991 Australian Census, Capital City Comparison Series, Religion, reported in Adam and Hughes, The Buddhists in Australia, Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, Australian Government Publishing Service, 1996. | + | Source: 1991 [[Australian]] Census, {{Wiki|Capital}} City Comparison Series, [[Religion]], reported in Adam and Hughes, The [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]], Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, [[Australian]] Government Publishing Service, 1996. |

City Number % of all % of population | City Number % of all % of population | ||

| − | === Buddhists in each city in Australia === | + | === [[Buddhists]] in each city in [[Australia]] === |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | Sydney 54,859 42.4 1.55 | + | {{Wiki|Sydney}} 54,859 42.4 1.55 |

| − | Melbourne 40,797 31.5 1.35 | + | {{Wiki|Melbourne}} 40,797 31.5 1.35 |

| − | Brisbane 8,631 6.7 0.65 | + | [[Brisbane]] 8,631 6.7 0.65 |

Adelaide 8,185 6.3 0.80 | Adelaide 8,185 6.3 0.80 | ||

| − | Perth 12,497 9.7 1.09 | + | {{Wiki|Perth}} 12,497 9.7 1.09 |

Hobart 412 0.3 0.23 | Hobart 412 0.3 0.23 | ||

| − | Darwin 1,077 0.8 1.37 | + | {{Wiki|Darwin}} 1,077 0.8 1.37 |

| − | Canberra 2,962 2.3 1.06 | + | {{Wiki|Canberra}} 2,962 2.3 1.06 |

Total 129,420 100.00 0.8 | Total 129,420 100.00 0.8 | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| − | === Buddhist organisations and temples in Australia === | + | === [[Buddhist]] organisations and [[temples]] in [[Australia]] === |

| − | Australia is fortunate in that all the major traditions and sects in world [[Buddhism]] can be found there. Each of the ethnic groups which migrated to Australia has tended to establish its own temples, often bringing out monks and nuns from the home country to provide religious leadership and teaching to the community. In addition, many groups of Westerners have set up [[Meditation]] groups, study centres and country retreats to further their practice of [[Buddhism]]. Table 4 gives details of the range and spread of Buddhist organisations throughout the nation. | + | [[Australia]] is [[fortunate]] in that all the major [[traditions]] and sects in [[world]] [[Buddhism]] can be found there. Each of the {{Wiki|ethnic}} groups which migrated to [[Australia]] has tended to establish its [[own]] [[temples]], often bringing out [[monks and nuns]] from the home country to provide [[religious]] [[leadership]] and [[teaching]] to the {{Wiki|community}}. In addition, many groups of [[Westerners]] have set up [[Meditation]] groups, study centres and country [[retreats]] to further their practice of [[Buddhism]]. Table 4 gives details of the range and spread of [[Buddhist]] organisations throughout the {{Wiki|nation}}. |

| − | Table 4: Buddhist organisations in Australia, by tradition, State and Territory, 1995 | + | Table 4: [[Buddhist]] organisations in [[Australia]], by [[tradition]], [[State]] and Territory, 1995 |

| − | Source: BuddhaNet, derived from lists prepared by Buddhist [[Council]] of New South Wales. | + | Source: BuddhaNet, derived from lists prepared by [[Buddhist]] [[Council]] of New {{Wiki|South}} [[Wales]]. |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | Buddhist NSW Vic Qld SA WA Tas NT Total | + | [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|NSW}} Vic Qld SA WA Tas NT Total |

| − | Tradition [[Theravada]] | + | [[Tradition]] [[Theravada]] |

| − | Burmese 1 - - - 2 - - 3 | + | [[Burmese]] 1 - - - 2 - - 3 |

| − | Cambodian 1 2 2 1 - - - 6 | + | [[Cambodian]] 1 2 2 1 - - - 6 |

| − | Indonesian 1 - - - - - - 1 | + | {{Wiki|Indonesian}} 1 - - - - - - 1 |

Lao 1 2 1 - - - - 4 | Lao 1 2 1 - - - - 4 | ||

Malaysian 1 - - - - - - 1 | Malaysian 1 - - - - - - 1 | ||

| − | Sri Lankan 2 1 1 1 1 - - 6 | + | [[Sri Lankan]] 2 1 1 1 1 - - 6 |

| − | Thai 3 3 1 1 - - - 8 | + | [[Thai]] 3 3 1 1 - - - 8 |

| − | Vipassana 1 1 2 - - - - 4 | + | [[Vipassana]] 1 1 2 - - - - 4 |

Other 7 2 2 1 3 1 1 16 | Other 7 2 2 1 3 1 1 16 | ||

| Line 149: | Line 161: | ||

[[Mahayana]] | [[Mahayana]] | ||

| − | Ch'an 1 - - - - - - 1 | + | [[Ch'an]] 1 - - - - - - 1 |

| − | Chinese 5 1 1 1 1 - - 9 | + | {{Wiki|Chinese}} 5 1 1 1 1 - - 9 |

Kegon/Tendai 1 - - - - - - 1 | Kegon/Tendai 1 - - - - - - 1 | ||

| − | Korean 1 - - - - - - 1 | + | [[Korean]] 1 - - - - - - 1 |

[[Pure land]] 4 2 - 1 3 - - 10 | [[Pure land]] 4 2 - 1 3 - - 10 | ||

Sinshu 1 - - - - - - 1 | Sinshu 1 - - - - - - 1 | ||

([[Japan]]) | ([[Japan]]) | ||

| − | Tibetan - - - - 1 1 - 2 | + | [[Tibetan]] - - - - 1 1 - 2 |

| − | Vietnamese 2 4 4 - - - - 10 | + | [[Vietnamese]] 2 4 4 - - - - 10 |

[[Zen]] 3 2 5 - 1 1 - 12 | [[Zen]] 3 2 5 - 1 1 - 12 | ||

Other 1 2 - - 1 1 - 5 | Other 1 2 - - 1 1 - 5 | ||

| Line 171: | Line 183: | ||

Total [[Vajrayana]] 15 6 5 3 4 2 1 36 | Total [[Vajrayana]] 15 6 5 3 4 2 1 36 | ||

| − | Western 2 1 - - - - - 3 | + | [[Western]] 2 1 - - - - - 3 |

| − | Buddhist | + | [[Buddhist]] |

| − | Non-Sectarian 10 4 4 1 2 - 1 22 | + | [[Non-Sectarian]] 10 4 4 1 2 - 1 22 |

Other 4 - 1 - - - - 5 | Other 4 - 1 - - - - 5 | ||

Total 68 33 29 9 19 6 3 167 | Total 68 33 29 9 19 6 3 167 | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| − | === Number of monks and nuns in Australia === | + | === Number of [[monks and nuns]] in [[Australia]] === |

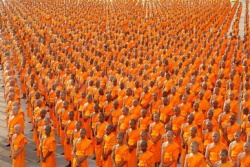

[[File:356011.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:356011.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | It is difficult to give a precise figure for the number of monks and nuns in Australia. Some members of [[The Sangha]] who are Australian residents may spend regular periods of time overseas, and at any time there would be a number of monks and nuns from overseas who are on extended visits to Australia. A reasonably conservative estimate would be that there are at least 200 monks and nuns in Australia. | + | It is difficult to give a precise figure for the number of [[monks and nuns]] in [[Australia]]. Some members of [[The Sangha]] who are [[Australian]] residents may spend regular periods of [[time]] overseas, and at any [[time]] there would be a number of [[monks and nuns]] from overseas who are on extended visits to [[Australia]]. A reasonably conservative estimate would be that there are at least 200 [[monks and nuns]] in [[Australia]]. |

| − | === Buddhist influences on Art and literature in Australia === | + | === [[Buddhist]] [[influences]] on [[Art]] and {{Wiki|literature}} in [[Australia]] === |

| − | A number of Australian artists and writers have been strongly influenced by Eastern philosophy, religion and aesthetics. These include the painters Godfrey Miller, Ian Fairweather, John Olsen, Brett Whiteley and Margaret Preston, and the poets Harold Stewart, Max Dunn, Colin Johnson and Robert Gray. These influences included [[Buddhism]], particularly [[Zen]] [[Buddhism]]. Some Australians were drawn to [[Buddhism]] through [[Art]] and literature. One of these was Les Oates who took up the practice of [[Zen]] during his time in [[Japan]] after the war and who started the Buddhist Society of Victoria in 1953, along with Len Henderson. Adrian Snodgrass, a lecturer in Architecture at the University of Sydney, has been influenced by [[Zen]] and [[Pure Land Buddhism]] and has published several authoritative works on Buddhist [[Art]]. | + | A number of [[Australian]] {{Wiki|artists}} and writers have been strongly influenced by Eastern [[philosophy]], [[religion]] and aesthetics. These include the painters Godfrey Miller, Ian Fairweather, John Olsen, Brett Whiteley and Margaret Preston, and the poets Harold Stewart, Max Dunn, Colin Johnson and Robert Gray. These [[influences]] included [[Buddhism]], particularly [[Zen]] [[Buddhism]]. Some [[Australians]] were drawn to [[Buddhism]] through [[Art]] and {{Wiki|literature}}. One of these was Les Oates who took up the practice of [[Zen]] during his [[time]] in [[Japan]] after the [[war]] and who started the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}} of Victoria in 1953, along with Len Henderson. [[Adrian Snodgrass]], a lecturer in [[Architecture]] at the {{Wiki|University}} of {{Wiki|Sydney}}, has been influenced by [[Zen]] and [[Pure Land Buddhism]] and has published several authoritative works on [[Buddhist]] [[Art]]. |

| − | === The future of Buddhism in Australia === | + | === The {{Wiki|future}} of [[Buddhism]] in [[Australia]] === |

| − | [[The History of Buddhism]] in Australia has passed through several stages. From its introduction to Australia until the 1960s, [[Buddhism]] was kept alive by a small number of dedicated Westerners. With increased migration to Australia from Asian countries from the 1970s, [[Buddhism]] entered a period of rapid growth. It now ranks as the third most populous religion in Australia, after | + | [[The History of Buddhism]] in [[Australia]] has passed through several stages. From its introduction to [[Australia]] until the 1960s, [[Buddhism]] was kept alive by a small number of dedicated [[Westerners]]. With increased migration to [[Australia]] from {{Wiki|Asian}} countries from the 1970s, [[Buddhism]] entered a period of rapid growth. It now ranks as the third most populous [[religion]] in [[Australia]], after {{Wiki|Christianity}} and {{Wiki|Islam}}. As immigration has now levelled off and may slow down even further, {{Wiki|future}} growth in [[Buddhism]] will have to come from within. There are both positive and negative indicators for such {{Wiki|future}} growth. |

| − | It is critical that young people from Buddhist families have the opportunity to learn [[ | + | It is critical that young [[people]] from [[Buddhist]] families have the opportunity to learn the [[Dharma]] so that they have a framework to guide their [[lives]] in the predominantly {{Wiki|secular}} and [[materialistic]] {{Wiki|culture}} of [[Australia]]. Many [[temples]] have educational programs, but these programs cannot reach all. [[Religious]] [[education]] for those of all [[faiths]] is provided in government schools, but there is a drastic shortage of volunteers from the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|community}} to provide this [[teaching]]. |

| − | Increasing numbers of Westerners are being drawn to [[Buddhism]], but for many this goes no further than reading [[About Buddhism]], or practicing [[Meditation]] to seek relaxation and peace of mind. For some it is difficult to become more actively engaged in [[Buddhism]] because the majority of Buddhist temples cater to specific ethnic groups, and Westerners may encounter [[Language]] or cultural barriers in attempting to get involved. It is important that temples seek to develop devotional and teaching modes which cater to the broader Australian community rather than to only one ethnic group. | + | {{Wiki|Increasing}} numbers of [[Westerners]] are {{Wiki|being}} drawn to [[Buddhism]], but for many this goes no further than reading [[About Buddhism]], or practicing [[Meditation]] to seek [[relaxation]] and [[peace]] of [[mind]]. For some it is difficult to become more actively engaged in [[Buddhism]] because the majority of [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] cater to specific {{Wiki|ethnic}} groups, and [[Westerners]] may encounter [[Language]] or {{Wiki|cultural}} barriers in attempting to get involved. It is important that [[temples]] seek to develop devotional and [[teaching]] modes which cater to the broader [[Australian]] {{Wiki|community}} rather than to only one {{Wiki|ethnic}} group. |

| − | Given the enormous diversity in Australian [[Buddhism]], there is a need for organisations which can provide a bridge and an opportunity for joint activity between the many Buddhist groups. In New South Wales, this function is performed by the Buddhist [[Council]] of New South Wales. It coordinates shared activities such as joint Vesak celebrations for all the traditions and ethnic groups to come together. It also provides representation to government and the media, distributes Buddhist literature, answers questions from the general public and directs them to the appropriate Buddhist organisation for further help. The newly formed Buddhist [[Council]] of Victoria performs a similar function in Victoria. | + | Given the enormous diversity in [[Australian]] [[Buddhism]], there is a need for organisations which can provide a bridge and an opportunity for joint [[activity]] between the many [[Buddhist]] groups. In New {{Wiki|South}} [[Wales]], this [[function]] is performed by the [[Buddhist]] [[Council]] of New {{Wiki|South}} [[Wales]]. It coordinates shared [[activities]] such as joint [[Vesak]] {{Wiki|celebrations}} for all the [[traditions]] and {{Wiki|ethnic}} groups to come together. It also provides [[representation]] to government and the media, distributes [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|literature}}, answers questions from the general public and directs them to the [[appropriate]] [[Buddhist]] organisation for further help. The newly formed [[Buddhist]] [[Council]] of Victoria performs a similar [[function]] in Victoria. |

| − | Provided that some problems can be overcome, [[Buddhism]] in Australia seems set for a period of growth which is steady but not as rapid as in the past 20 years. May we find support in the [[Triple Gem]] for our efforts, and may all beings be well and happy in [[ | + | Provided that some problems can be overcome, [[Buddhism]] in [[Australia]] seems set for a period of growth which is steady but not as rapid as in the {{Wiki|past}} 20 years. May we find support in the [[Triple Gem]] for our efforts, and may all [[beings]] be well and [[happy]] in the [[Dharma]]. |

=== References === | === References === | ||

| − | The Buddhists in Australia, Enid Adam and Philip J. Hughes, Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, Australian Government Publishing Service, 1996. | + | The [[Buddhists]] in [[Australia]], Enid Adam and Philip J. Hughes, Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, [[Australian]] Government Publishing Service, 1996. |

| − | A History of [[Buddhism]] in Australia 1848-1988, Paul Croucher, New South Wales University Press, Sydney, 1989.Many Faiths One Nation, edited by Ian Gillman, William Collins, Sydney, 1988. | + | A {{Wiki|History}} of [[Buddhism]] in [[Australia]] 1848-1988, Paul Croucher, New {{Wiki|South}} [[Wales]] {{Wiki|University}} Press, {{Wiki|Sydney}}, 1989.Many [[Faiths]] One Nation, edited by Ian Gillman, William Collins, {{Wiki|Sydney}}, 1988. |

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

| Line 209: | Line 221: | ||

[[Category:History of Buddhism]] | [[Category:History of Buddhism]] | ||

[[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Buddhism in Australia]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:53, 16 February 2024

This article was first published in the Vietnamese Buddhist journal Giac Ngo (in a translation into Vietnamese by the Ven. Thich Nguyen Tang and later this was published by Kerry Trembath, Sydney, November 1996).

First contacts with Buddhism

It is not known precisely when Buddhism first came to Australia. Professor A.P. Elkin has argued that there may have been contact between the Aboriginal people of northern Australia and the early Hindu-Buddhist civilisations of Indonesia. He suggests that Aboriginal practices of mind training and belief in Reincarnation may be evidence of such contact. It is also possible that the great fleets of the Chinese Ming emperors which explored the south between 1405 and 1433 may have reached the mainland of Australia.

The first certain contact with Buddhism can be dated to 1848, when Chinese labourers arrived to work on the goldfields of eastern Australia. The beliefs of these men were predominantly Taoist/Confucian, but the makeshift temples they built have been found to contain remnants of Mahayana Buddhist statues. Most of these men returned to China when the goldrush ended, but some stayed in Australia, often after sending for a wife from China. While the older Chinese continued to practice their ancestral beliefs, their children and grandchildren often adopted the Christian Faith.

In the 1870s, groups of Sinhalese from Sri Lanka began to arrive in Australia to work on the sugar plantations of northern Queensland, or in the pearling industry centred on Thursday Island. By the 1890s, the Buddhist population of Thursday Island included about 500 Sinhalese people. Two Bodhi trees planted by this community are still growing on Thursday Island to this day. A temple was built on Thursday Island, festivals such as Vesak were regularly celebrated, and a Buddhist monk is said to have visited to officiate at the temple around the turn of the century.

Soon after Federation in 1901, Australia adopted increasingly restrictive immigration policies which effectively halted further Asian immigration until the 1960s.

Early Western Buddhists in Australia

By the late 1800s, increasing numbers of Westerners were becoming interested in Asian culture and religion. In 1891, Colonel Henry Steel Olcott spent several months lecturing throughout Australia on `Theosophy and Buddhism'. Olcott was the co-founder of the Theosophical Society who described himself as a Buddhist, having taken the three refuges and The Five Precepts in Sri Lanka in 1880. His lectures in Australia were well attended and well received. Small but significant numbers of generally well-educated and influential Australians joined the Theosophical Society, the aim of which, according to Olcott, was to disseminate Buddhist Philosophy. One of those who joined the Theosophical Society at this time was Alfred Deakin, who was later to be three times Prime Minister of Australia. Deakin retained a lifetime Interest in and regard for Buddhism and even wrote a book about a visit to India and Sri Lanka which included three chapters which were highly sympathetic to Buddhism.

In time, the Theosophical Society drifted away from its strong focus on Buddhism, becoming more eclectic and giving greater emphasis to spiritualism and occultism. Nevertheless, the importance of the Theosophical Society in the early history of Buddhism in Australia cannot be overlooked. To this day, the Society's bookshop in Sydney, Adyar, remains one of the best sources of Buddhist literature in the country.

Another important figure in the Theosophical Society made a contribution to The History of Buddhism in Australia. In 1919, F.L. Woodward, who for 16 years had been principal of Mahinda College in Galle, Sri Lanka, arrived in Australia. He settled on an apple orchard near Launceston in Tasmania, and for the next 33 years devoted his time to translations of the Pali Canon for the Pali Text Society. He is perhaps best known for his anthology, Some Sayings of The Buddha, first published in 1925. This popular book provided an introduction to Buddhism for many Westerners, including some who later became prominent Australian Buddhists.

The earliest group of Western Buddhists in Australia, The Little Circle of the Dharma, may have been formed in 1925 in Melbourne by Max Tyler, Max Dunn and David Maurice. This group was strongly influenced by the Theravada tradition of Burma. By the 1950s, David Maurice was editing The Light of the Dhamma, a Buddhist magazine in English which had a wide circulation throughout the world, and in 1962 he published The Lion's Roar, his anthology of the Pali Canon. Another early group was established in Melbourne in 1938 by Leonard Bullen, and was called The Buddhist Study Group. Unfortunately, the outbreak of the second World War in 1939 put a stop to this promising start.

Women played an important part in the development of Buddhism in Australia. Marie Byles, the first woman solicitor in the country and also a prominent conservationist, feminist and pacifist, wrote many Books and articles on Buddhism in the 1940s and 1950s. Only one of her Books, Footprints of Gautama The Buddha, is still in print. She gave many talks in Sydney as well as broadcasting on the Theosophical Society's regular Sunday night radio program on Radio Station 2GB. Marie Byles studied Vipassana Meditation in Burma, and built a Meditation hut in the garden of her Sydney home which is still there to this day. Her home and garden have been given to the people of Sydney as a quiet Retreat. Her extensive library of Buddhist Books, including a full set of the Tripitika in English, was bequeathed to the library of the University of Sydney.

In 1952, the first Buddhist nun visited Australia. Sister Dhammadina, born in the USA and with thirty years experience in Sri Lanka, was sponsored by Dr Malasekera, the first president of the World Fellowship of Buddhists. Although she was already 70 years old, Sister Dhammadina was enterprising and energetic, and her 11 months in Sydney helped to further the growing Interest in Buddhism.

The first Buddhist societies in Australia

Around this time, the Buddhist Society of New South Wales, Australia's oldest surviving Buddhist society, was established by Leo Berkeley, a Sydney businessman. A leading member of this group was Natasha Jackson, who edited the publication Metta from 1955 (originally Buddhist News, edited by Gordon Lishman) and who exerted a powerful influence on the development of Australian Buddhism over the next 20 years. In 1953, the Buddhist Society of Victoria and the Buddhist Society of Queensland were established. Until the 1960s, the focus in Sydney was strongly Theravadin while in Melbourne it was more eclectic with both Theravadin and Japanese Zen influences. In 1973, the Buddhist Society of Western Australia was formed in Perth. This society was also primarily Theravadin.

In 1958, the Sydney-based Buddhist Federation of Australia was formed with Charles Knight as its chairperson and Natasha Jackson as a central figure. The Federation took over publication of Metta, later renaming it Buddhism Today. This journal is still published to this day, making it the oldest continuing Buddhist publication in Australia.

The Chinese Buddhist Society of Australia was established in Sydney in 1972 by businessman Eric Liao, who had arrived in Australia in 1961.

Visits to Australia by Sangha from overseas

In 1954, Venerable U Thittila came to Australia from Burma in the first of his three trips to give talks and guidance to the newly formed Buddhist societies. Venerable Narada Thera came a year later from Sri Lanka at the invitation of the Buddhist Society of Queensland. Sister Dhammadina returned to Australia in 1957. These visits received extensive publicity, and during this time the membership of the Buddhist societies doubled to around 100 in Sydney and 40 in Melbourne. As in the past, the majority of those drawn to Buddhism were well educated, in professional or managerial occupations, or in the arts and literature.

During the 1960s, notable visitors included the abbot of Higashi Hongan-ji temple in Kyoto; the Venerable Piyadassi Thera from Sri Lanka; the famous Vietnamese teacher and writer, the Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh; and the Venerable Phra Sasanasobhon, chair of the Mahamakut Educational Foundation of Thailand.

The establishment of Mahayana in Australia

A master of the Chinese Zen tradition arrived in Sydney from Hong Kong in 1961. He was Hsuan Hua, also known as An-tz'u and To-lun. Language difficulties and the strong Theravada orientation of Western Buddhists in Sydney limited his impact and he left in 1961 to go to California where he later founded the monastic complex, `City of the Ten Thousand Buddhas'. The Soto Zen Buddhist Society was formed in Sydney in 1961, and the Sydney Zen Centre was established in 1976. This centre was associated with the Soto Zen Diamond Sangha in Hawaii. Robert Aitken Roshi, the director of the Hawaiian centre, visited annually in the early years, and his Australian-born disciple, John Tarrant Roshi (now living in California) has continued his work. During the 1970s and 1980s, small groups dedicated to the practice of Zen were formed in Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth.

The first monasteries in Australia

During the 1970s, there was a strong growth of Interest in Buddhism, especially among young people. During this period, it has been estimated that close to 300 Australians attended the annual retreats in northern India and Nepal conducted by Tibetan teachers such as Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa. In Thailand, perhaps as many as 200 Australians may have been ordained as monks for various periods of time in Thailand. By this time also, large numbers of immigrants and refugees from Asia were coming to Australia to settle, and many of these were Buddhists. The time was ripe for establishment of the first Buddhist monasteries in Australia.

The Venerable Somaloka, a young Sri Lankan Monk, arrived in Sydney in 1971, initially at the invitation of the Buddhist Society of New South Wales. On Vesak Day, 1973, the Australian Buddhist Vihara was opened at Katoomba in the Blue Mountains, a short distance to the west of Sydney. This was the first monastery in Australia. Venerable Somaloka still resides there, but the temple has never been attended by large numbers of Buddhists and its influence on the growth of Buddhism in Australia has been limited.

In 1973, Venerable Phra Khantipalo, an English-born Monk from Wat Bovoranives in Thailand, arrived in Sydney. Shortly later, he was followed by Phra Chao Khun Pariyattikavee from the Mahamakut Foundation in Thailand. Phra Khantipalo spent the next 2 years teaching throughout Australia. On Vesak Day, 1995, Wat Buddharangsee (`monastery of The Buddha's radiance') was opened at Stanmore in Sydney by the Crown Prince of Thailand in the presence of Phra Khantipalo and his teacher, Somdet Phra Nyanasamsvara, and 7 other visiting abbots. Under the leadership of its abbot Phra Mahasamai, this temple served not only the Thai community in Sydney, but also Laotian, Cambodian, Burmese, Malaysian, and even Vietnamese and Chinese Buddhists before these groups were in a position to set up their own temples. Phra Mahasamai, now Tan Chao Khun Samai, still works tirelessly for the betterment of the whole Buddhist community in Sydney.

In 1978, Phra Khantipalo and the German-born nun Ayya Khema established Wat Buddha Dhamma in a bushland setting at Wiseman's Ferry north of Sydney. This functioned mainly as a centre for Meditation and retreats, and appealed to many Westerners who were attracted to Buddhism.

Soon, other ethnic groups (Cambodian, Laotian, Burmese, Sri Lankans and Vietnamese) were establishing temples, mainly in Sydney and Melbourne where these groups had settled in largest numbers. A Chinese temple was established in Sydney's Chinatown district in 1972. This was followed by the Hwa Tsang Monastery at Homebush, where the first and still current abbot was the Venerable Tsang Hui.

Vietnamese Buddhist organisations in Australia

Vietnamese Buddhist temples began to be established in the 1980s. In 1981, the senior Vietnamese Buddhist monk, the Most Venerable Thich Phuoc Hue, arrived in Australia to form the Vietnamese Buddhist Federation of Australia. This organisation, now known as the United Vietnamese Congregations of Australia, has branch temples in all Australian states except Tasmania. Other prominent Vietnamese groups are the Vietnamese Buddhist Society of New South Wales (Venerable Thich Bao Lac), the Lotus Buds Sangha (followers of Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh), Linn Son (with headquarters in France and centres in Queensland and Victoria) and the Middle Way (Venerable Thich Minh Thien of The Buddha Relics Vihara in Sydney).. Their temples usually follow Mahayana traditions, especially Pure land and Ch'an, and the Bodhisattva Kuan yin is frequently venerated. Many temples also have youth groups and offer part-time classes in Vietnamese Language and customs to help young people born in Australia to maintain their culture.

Tibetan Buddhism in Australia

Although the number of Tibetans in Australia is relatively small, the Vajrayana tradition is very attractive to many Westerners and the Tibetan influence in Australian Buddhism is strong. For example, nearly one third of all Buddhist organisations in Sydney is Tibetan. The Dalai Lama has visited Australia three times (1982, 1992 and 1996) and on each occasion he has drawn huge crowds of the general public as well as giving great Joy and inspiration to Buddhists of all traditions.

Numbers of Buddhists in Australia

Although many Australians are interested in Buddhism, the number of Westerners who identify themselves as Buddhists is still very small. Most Buddhists in Australia are immigrants from Asia.

From Table 1, which has been taken from figures published by the Australian government from the 1991 Census, it can be seen that people of Vietnamese origin are the largest single ethnic group of Buddhists, and that they make up nearly one third of all Australian Buddhists. Not all people born in Viet Nam were Buddhist - 35% of them identified as Catholic, and 60% as Buddhist.

Less than a quarter of all Australian Buddhists were born in Australia, and of those, only one quarter had both parents born in Australia.

Chinese Buddhists came from many countries, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia as well as the People's Republic of China.

Growth in Buddhism in Australia

Numbers grew rapidly between 1981 and 1991, increasing by almost 300%. Buddhists have become Australia's fastest growing religious group, but they are still less than one percent of the Australian population (Table 2).

Table 2: Buddhists by State and Territory,and as percentage of Australian population, 1891-1991

Source: Australian Census figures, reported in Adam and Hughes, The Buddhists in Australia, Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, Australian Government Publishing Service, 1996.

Year NSW Vic Qld SA WA Tas NT ACT Total %

1891 10,120 6,746 - 3,936 1,089 826 - - 22,717 1.2

1901 5,471 4,807 - 3,190 844 353 - - 14,665 0.5

1911 3,516 1,273 3,327 97 2,265 169 1,317 0 11,964 0.3

1921 2,790 1,063 1,931 149 1,667 70 672 6 8,348 0.2

1933 850 177 324 59 354 3 55 5 1,827 -

1947 450 201 102 12 90 9 62 0 926 -

1981 15,635 9,474 2,967 2,229 2,971 236 499 1,062 35,073 0.2

1986 35,112 23,265 5,768 5,847 7,177 439 885 1,890 80,383 0.5

1991 58,735 42,349 11,638 8,529 13,499 713 1,370 2,962 139,795 0.8

Geographical spread of Buddhists in Australia

The geographical distribution of Buddhists in Australia reflects the destinations of recent immigrants. Almost all settled in the capital cities, and most (around 79%) settled in Sydney and Melbourne (Table 3). Although the percentage of Buddhists in Australia is only around 0.8%, they form a more significant proportion of the population in Sydney, Melbourne and Darwin.

Table 3: Buddhists living in the capital cities of Australia

Source: 1991 Australian Census, Capital City Comparison Series, Religion, reported in Adam and Hughes, The Buddhists in Australia, Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, Australian Government Publishing Service, 1996.

City Number % of all % of population

Buddhists in each city in Australia

Sydney 54,859 42.4 1.55

Melbourne 40,797 31.5 1.35

Brisbane 8,631 6.7 0.65

Adelaide 8,185 6.3 0.80

Perth 12,497 9.7 1.09

Hobart 412 0.3 0.23

Darwin 1,077 0.8 1.37

Canberra 2,962 2.3 1.06

Total 129,420 100.00 0.8

Buddhist organisations and temples in Australia

Australia is fortunate in that all the major traditions and sects in world Buddhism can be found there. Each of the ethnic groups which migrated to Australia has tended to establish its own temples, often bringing out monks and nuns from the home country to provide religious leadership and teaching to the community. In addition, many groups of Westerners have set up Meditation groups, study centres and country retreats to further their practice of Buddhism. Table 4 gives details of the range and spread of Buddhist organisations throughout the nation.

Table 4: Buddhist organisations in Australia, by tradition, State and Territory, 1995

Source: BuddhaNet, derived from lists prepared by Buddhist Council of New South Wales.

Buddhist NSW Vic Qld SA WA Tas NT Total

Tradition Theravada

Burmese 1 - - - 2 - - 3

Cambodian 1 2 2 1 - - - 6

Indonesian 1 - - - - - - 1

Lao 1 2 1 - - - - 4

Malaysian 1 - - - - - - 1

Sri Lankan 2 1 1 1 1 - - 6

Thai 3 3 1 1 - - - 8

Vipassana 1 1 2 - - - - 4

Other 7 2 2 1 3 1 1 16

Theravada

Total Theravada 18 11 9 3 6 1 1 49

Mahayana

Ch'an 1 - - - - - - 1

Chinese 5 1 1 1 1 - - 9

Kegon/Tendai 1 - - - - - - 1

Korean 1 - - - - - - 1

Pure land 4 2 - 1 3 - - 10

Sinshu 1 - - - - - - 1

(Japan)

Tibetan - - - - 1 1 - 2

Vietnamese 2 4 4 - - - - 10

Zen 3 2 5 - 1 1 - 12

Other 1 2 - - 1 1 - 5

Mahayana

Total Mahayana 19 11 10 2 7 3 0 52

Vajrayana

Dzogchen 4 2 - - 1 - - 7

Other 11 4 5 3 3 2 1 29

Vajrayana

Total Vajrayana 15 6 5 3 4 2 1 36

Western 2 1 - - - - - 3

Buddhist

Non-Sectarian 10 4 4 1 2 - 1 22

Other 4 - 1 - - - - 5

Total 68 33 29 9 19 6 3 167

Number of monks and nuns in Australia

It is difficult to give a precise figure for the number of monks and nuns in Australia. Some members of The Sangha who are Australian residents may spend regular periods of time overseas, and at any time there would be a number of monks and nuns from overseas who are on extended visits to Australia. A reasonably conservative estimate would be that there are at least 200 monks and nuns in Australia.

Buddhist influences on Art and literature in Australia

A number of Australian artists and writers have been strongly influenced by Eastern philosophy, religion and aesthetics. These include the painters Godfrey Miller, Ian Fairweather, John Olsen, Brett Whiteley and Margaret Preston, and the poets Harold Stewart, Max Dunn, Colin Johnson and Robert Gray. These influences included Buddhism, particularly Zen Buddhism. Some Australians were drawn to Buddhism through Art and literature. One of these was Les Oates who took up the practice of Zen during his time in Japan after the war and who started the Buddhist Society of Victoria in 1953, along with Len Henderson. Adrian Snodgrass, a lecturer in Architecture at the University of Sydney, has been influenced by Zen and Pure Land Buddhism and has published several authoritative works on Buddhist Art.

The future of Buddhism in Australia

The History of Buddhism in Australia has passed through several stages. From its introduction to Australia until the 1960s, Buddhism was kept alive by a small number of dedicated Westerners. With increased migration to Australia from Asian countries from the 1970s, Buddhism entered a period of rapid growth. It now ranks as the third most populous religion in Australia, after Christianity and Islam. As immigration has now levelled off and may slow down even further, future growth in Buddhism will have to come from within. There are both positive and negative indicators for such future growth.

It is critical that young people from Buddhist families have the opportunity to learn the Dharma so that they have a framework to guide their lives in the predominantly secular and materialistic culture of Australia. Many temples have educational programs, but these programs cannot reach all. Religious education for those of all faiths is provided in government schools, but there is a drastic shortage of volunteers from the Buddhist community to provide this teaching.

Increasing numbers of Westerners are being drawn to Buddhism, but for many this goes no further than reading About Buddhism, or practicing Meditation to seek relaxation and peace of mind. For some it is difficult to become more actively engaged in Buddhism because the majority of Buddhist temples cater to specific ethnic groups, and Westerners may encounter Language or cultural barriers in attempting to get involved. It is important that temples seek to develop devotional and teaching modes which cater to the broader Australian community rather than to only one ethnic group.

Given the enormous diversity in Australian Buddhism, there is a need for organisations which can provide a bridge and an opportunity for joint activity between the many Buddhist groups. In New South Wales, this function is performed by the Buddhist Council of New South Wales. It coordinates shared activities such as joint Vesak celebrations for all the traditions and ethnic groups to come together. It also provides representation to government and the media, distributes Buddhist literature, answers questions from the general public and directs them to the appropriate Buddhist organisation for further help. The newly formed Buddhist Council of Victoria performs a similar function in Victoria.

Provided that some problems can be overcome, Buddhism in Australia seems set for a period of growth which is steady but not as rapid as in the past 20 years. May we find support in the Triple Gem for our efforts, and may all beings be well and happy in the Dharma.

References

The Buddhists in Australia, Enid Adam and Philip J. Hughes, Bureau of Immigration, Multicultural and Population Research, Australian Government Publishing Service, 1996.

A History of Buddhism in Australia 1848-1988, Paul Croucher, New South Wales University Press, Sydney, 1989.Many Faiths One Nation, edited by Ian Gillman, William Collins, Sydney, 1988.