Difference between revisions of "Two Truths"

| (13 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

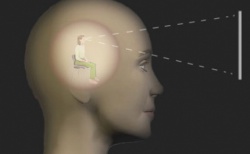

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:Mind-Power.jpg|thumb|250px|]] |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | By Barbara O'Brien | + | By [[Barbara O'Brien]] |

| + | [[Two Truths]] | ||

| + | 1) [[Relative]] or [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]], everyday [[truth]] of the [[mundane world]] [[subject]] to [[delusion]] and dichotomies and 2) the [[Ultimate Truth]], transcending dichotomies, as [[taught]] by the [[Buddhas]]. According to [[Buddhism]], there are two kinds of [[Truth]], the [[Absolute]] and the [[Relative]]. The [[Absolute Truth]] (of the [[Void]]) [[manifests]] "[[illumination]] but is always still," and this is absolutely inexplicable. On the other hand, the [[Relative Truth]] (of the Unreal) [[manifests]] "stillness but is always [[illuminating]]," which means that it is immanent in everything. ([[Hsu Heng Chi]]/P.H. Wei). | ||

| + | [[Pure Land]] thinkers such as the [[Patriarch]] [[Tao Ch'o]] accepted "the legitimacy of [[Conventional Truth]] as an expression of [[Ultimate Truth]] and as a [[vehicle]] to reach [[Ultimate Truth]]. Even though all [[form]] is nonform, it is acceptable and necessary to use [[form]] within the limits of [[causality]], because its use is an [[expedient means]] of saving others out of one's [[compassion]] for them and because, even for the unenlightened, the use of [[form]] can lead to the [[revelation]] of [[form]] as nonform" (David Chappell). Thus to reach [[Buddhahood]], which is [[formless]], the cultivator can [[practice]] the [[Pure Land]] method based on [[form]]. | ||

| + | What is {{Wiki|reality}}? {{Wiki|Dictionaries}} tell us that [[reality]] is "the [[state]] of things as they actually [[exist]]." In [[Mahayana]] [[Buddhism]], [[reality]] is explained in the [[doctrine]] of the [[Two Truths]]. This [[doctrine]] tells us that {{Wiki|existence}} can be understood as both {{Wiki|ultimate}} and {{Wiki|conventional}} (or, [[absolute]] and {{Wiki|relative}}). [[Conventional truth]] is how we usually see the {{Wiki|world}}, a place full of diverse and {{Wiki|distinctive}} things and [[beings]]. The [[ultimate truth]] is that there are no {{Wiki|distinctive}} things or [[beings]]. | ||

| + | To say there are no {{Wiki|distinctive}} things or [[beings]] is not to say that [[nothing]] {{Wiki|exists}}; it is saying that there are no {{Wiki|distinctions}}. The [[absolute]] is the [[dharmakaya]], the {{Wiki|unity}} of all things and [[beings]], [[unmanifested]]. The late [[Chogyam Trungpa]] called the [[dharmakaya]] "the basis of the original [[unbornness]]." | ||

| − | + | Confused? You are not alone. It's not an easy [[teaching]] to "get," but it's critical to [[understanding]] [[Mahayana]] [[Buddhism]]. What follows is a very basic introduction to the [[Two Truths]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Confused? You are not alone. It's not an easy teaching to "get," but it's critical to understanding [[Mahayana]] [[Buddhism]]. What follows is a very basic introduction to the [[Two Truths]]. | ||

[[Nagarjuna]] and [[Madhyamika]] | [[Nagarjuna]] and [[Madhyamika]] | ||

| Line 18: | Line 17: | ||

In the [[Kaccayanagotta Sutta]] ([[Samyutta Nikaya]] 12.15) the [[Buddha]] said, | In the [[Kaccayanagotta Sutta]] ([[Samyutta Nikaya]] 12.15) the [[Buddha]] said, | ||

| − | + | "By and large, [[Kaccayana]], this [[world]] is supported by (takes as its {{Wiki|object}}) a {{Wiki|polarity}}, that of {{Wiki|existence}} and {{Wiki|non-existence}}. But when one sees the origination of the {{Wiki|world}} as it actually is with right [[discernment]], '{{Wiki|non-existence}}' with reference to the {{Wiki|world}} does not occur to one. When one sees the {{Wiki|cessation}} of the {{Wiki|world}} as it actually is with right [[discernment]], '{{Wiki|existence}}' with reference to the {{Wiki|world}} does not occur to one." | |

| − | The {{Wiki|Buddha}} also {{Wiki|taught}} that all [[phenomena]] manifest because of conditions created by other [[phenomena]] ([[dependent origination]]). But what are the nature of these conditioned {{Wiki|phenomena}}? | + | The {{Wiki|Buddha}} also {{Wiki|taught}} that all [[phenomena]] [[manifest]] because of [[conditions]] created by other [[phenomena]] ([[dependent origination]]). But what are the [[nature]] of these [[conditioned]] {{Wiki|phenomena}}? |

| − | An early school of [[Buddhism]], [[Mahasanghika]], had developed a [[doctrine]] called [[sunyata]], which proposed that all [[phenomena]] are empty of {{Wiki|self}}-{{Wiki|essence}}. [[Nagarjuna]] developed [[sunyata]] further. He saw {{Wiki|existence}} as a field of ever-changing conditions that cause {{Wiki|myriad}} [[phenomena]]. But the [[myriad]] [[phenomena]] are empty of {{Wiki|self}}-{{Wiki|essence}} and take {{Wiki|identity}} only in relation to other [[phenomena]]. | + | An early school of [[Buddhism]], [[Mahasanghika]], had developed a [[doctrine]] called [[sunyata]], which proposed that all [[phenomena]] are [[empty]] of {{Wiki|self}}-{{Wiki|essence}}. [[Nagarjuna]] developed [[sunyata]] further. He saw {{Wiki|existence}} as a field of ever-changing [[conditions]] that [[cause]] {{Wiki|myriad}} [[phenomena]]. But the [[myriad]] [[phenomena]] are [[empty]] of {{Wiki|self}}-{{Wiki|essence}} and take {{Wiki|identity}} only in [[relation]] to other [[phenomena]]. |

| − | Echoing the words of the [[Buddha]] in the [[Kaccayanagotta Sutta]], [[Nagarjuna]] said that one cannot truthfully say that [[phenomena]] either exist or don't exist. [[Madhyamika]] means "the [[middle way]]," and it is a [[middle way]] between {{Wiki|negation}} and {{Wiki|affirmation}}. | + | Echoing the words of the [[Buddha]] in the [[Kaccayanagotta Sutta]], [[Nagarjuna]] said that one cannot truthfully say that [[phenomena]] either [[exist]] or don't [[exist]]. [[Madhyamika]] means "the [[middle way]]," and it is a [[middle way]] between {{Wiki|negation}} and {{Wiki|affirmation}}. |

The [[Two Truths]] | The [[Two Truths]] | ||

| − | Now we get to the [[Two Truths]]. Looking around us, we see {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[phenomena]]. As I write this I see a cat sleeping on a chair, for example. In {{Wiki|conventional}} view, the cat and the chair are two {{Wiki|distinctive}} and {{Wiki|separate}} [[phenomena]]. | + | Now we get to the [[Two Truths]]. Looking around us, we see {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[phenomena]]. As I write this I see a {{Wiki|cat}} [[sleeping]] on a chair, for example. In {{Wiki|conventional}} [[view]], the {{Wiki|cat}} and the chair are two {{Wiki|distinctive}} and {{Wiki|separate}} [[phenomena]]. |

[[File:Sb31.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Sb31.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Further, the two [[phenomena]] have many component parts. The chair is made of fabric and "stuffing" and a frame. It has a back and arms and a seat. Lily the cat has fur and limbs and whiskers and organs. These parts can be further reduced to {{Wiki|atoms}}. I understand that atoms can be further reduced somehow, but I'll let the {{Wiki|physicists}} sort that out. | + | Further, the two [[phenomena]] have many component parts. The chair is made of fabric and "stuffing" and a frame. It has a back and arms and a seat. Lily the {{Wiki|cat}} has fur and limbs and whiskers and {{Wiki|organs}}. These parts can be further reduced to {{Wiki|atoms}}. I understand that [[atoms]] can be further reduced somehow, but I'll let the {{Wiki|physicists}} sort that out. |

| − | Notice the way the English {{Wiki|language}} causes us to speak of the chair and of Lily as if their {{Wiki|component}} parts are attributes belonging to a {{Wiki|self}}-nature. We say the chair has this and Lily has that. But the [[doctrine]] of [[sunyata]] says that these component parts are empty of self-nature; they are a temporary confluence of conditions. There is no-thing that possesses the fur or the fabric. | + | [[Notice]] the way the English {{Wiki|language}} [[causes]] us to speak of the chair and of Lily as if their {{Wiki|component}} parts are [[attributes]] belonging to a {{Wiki|self}}-[[nature]]. We say the chair has this and Lily has that. But the [[doctrine]] of [[sunyata]] says that these component parts are [[empty]] of [[self-nature]]; they are a temporary confluence of [[conditions]]. There is no-thing that possesses the fur or the fabric. |

| − | Further, the distinctive appearance of these [[phenomena]] -- the way we see and {{Wiki|experience}} them -- is in large part created by our own {{Wiki|nervous systems}} and sense organs. And the identities "chair" and "Lily" are my own {{Wiki|projections}}. In other {{Wiki|words}}, they are {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[phenomena]] in my head, not in themselves. This {{Wiki|distinction}} is [[conventional truth]]. | + | Further, the {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[appearance]] of these [[phenomena]] -- the way we see and {{Wiki|experience}} them -- is in large part created by our [[own]] {{Wiki|nervous systems}} and [[sense organs]]. And the {{Wiki|identities}} "chair" and "Lily" are my [[own]] {{Wiki|projections}}. In other {{Wiki|words}}, they are {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[phenomena]] in my head, not in themselves. This {{Wiki|distinction}} is [[conventional truth]]. |

| − | (I assume I appear as a distinctive [[phenomenon]] to Lily, or at least as some kind of complex of {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[phenomena]], and perhaps she projects some kind of identity onto me. At least, she doesn't seem to confuse me with the refrigerator.) | + | (I assume I appear as a {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[phenomenon]] to Lily, or at least as some kind of complex of {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[phenomena]], and perhaps she projects some kind of [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] onto me. At least, she doesn't seem to confuse me with the refrigerator.) |

| − | But in the [[absolute]] there are no distinctions. The [[absolute]] is described with {{Wiki|words}} like boundless, pure, and perfect. And this boundless, pure {{Wiki|perfection}} is as true of our {{Wiki|existence}} as fabric, fur, skin, scales, feathers, or whatever the case may be. | + | But in the [[absolute]] there are no {{Wiki|distinctions}}. The [[absolute]] is described with {{Wiki|words}} like [[boundless]], [[pure]], and {{Wiki|perfect}}. And this [[boundless]], [[pure]] {{Wiki|perfection}} is as true of our {{Wiki|existence}} as fabric, fur, {{Wiki|skin}}, scales, feathers, or whatever the case may be. |

[[File:Ization-430.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Ization-430.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Also the {{Wiki|relative}} or {{Wiki|conventional}} {{Wiki|reality}} is made up of things that can be reduced to smaller things down to atomic and sub-atomic levels. Composites of composites of composites. But the absolute is not a composite. | + | Also the {{Wiki|relative}} or {{Wiki|conventional}} {{Wiki|reality}} is made up of things that can be reduced to smaller things down to [[atomic]] and sub-atomic levels. Composites of composites of composites. But the [[absolute]] is not a composite. |

In the {{Wiki|Heart Sutra}}, we read, "{{Wiki|Form}} is no other than [[emptiness]]; [[emptiness]] no other than {{Wiki|form}}. {{Wiki|Form}} is exactly [[emptiness]]; [[emptiness]] exactly {{Wiki|form}}." The [[absolute]] is the {{Wiki|relative}}, the {{Wiki|relative}} is the [[absolute]]. Together, they make up {{Wiki|reality}}. | In the {{Wiki|Heart Sutra}}, we read, "{{Wiki|Form}} is no other than [[emptiness]]; [[emptiness]] no other than {{Wiki|form}}. {{Wiki|Form}} is exactly [[emptiness]]; [[emptiness]] exactly {{Wiki|form}}." The [[absolute]] is the {{Wiki|relative}}, the {{Wiki|relative}} is the [[absolute]]. Together, they make up {{Wiki|reality}}. | ||

| − | Common Confusion | + | Common {{Wiki|Confusion}} |

| − | A couple of common ways that people misunderstand the [[Two Truths]] -- | + | A couple of common ways that [[people]] misunderstand the [[Two Truths]] -- |

| − | One, people sometimes create a true-false {{Wiki|dichotomy}} and think that the [[absolute]] is true {{Wiki|reality}} and the {{Wiki|conventional}} is false {{Wiki|reality}}. But remember, these are the [[two truths]], not the one {{Wiki|truth}} and one lie. Both {{Wiki|truths}} are {{Wiki|true}}. | + | One, [[people]] sometimes create a true-false {{Wiki|dichotomy}} and think that the [[absolute]] is true {{Wiki|reality}} and the {{Wiki|conventional}} is false {{Wiki|reality}}. But remember, these are the [[two truths]], not the one {{Wiki|truth}} and one lie. Both {{Wiki|truths}} are {{Wiki|true}}. |

| − | Two, [[absolute]] and {{Wiki|relative}} are often described as different levels of {{Wiki|reality}}, but that may not be the best way to describe it. [[Absolute]] and {{Wiki|relative}} are not separate; nor is one higher or lower than the other. This is a nitpicky {{Wiki|semantic}} point, perhaps, but I think the {{Wiki|word}} level could create a misunderstanding. | + | Two, [[absolute]] and {{Wiki|relative}} are often described as different levels of {{Wiki|reality}}, but that may not be the best way to describe it. [[Absolute]] and {{Wiki|relative}} are not separate; nor is one higher or lower than the other. This is a nitpicky {{Wiki|semantic}} point, perhaps, but I think the {{Wiki|word}} level could create a {{Wiki|misunderstanding}}. |

Going Beyond | Going Beyond | ||

| − | Another common misunderstanding is that "[[enlightenment]]" means one has shed {{Wiki|conventional}} {{Wiki|reality}} and perceives only the [[absolute]]. But the [[sages]] tell us that [[enlightenment]] actually is going beyond both. The [[Chan]] [[patriarch]] {{Wiki|Seng-ts'an}} (d. 606 CE) wrote in the {{Wiki|Xinxin Ming}} ({{Wiki|Hsin Hsin Ming}}): | + | Another common {{Wiki|misunderstanding}} is that "[[enlightenment]]" means one has shed {{Wiki|conventional}} {{Wiki|reality}} and [[perceives]] only the [[absolute]]. But the [[sages]] tell us that [[enlightenment]] actually is going beyond both. The [[Chan]] [[patriarch]] {{Wiki|Seng-ts'an}} (d. 606 CE) wrote in the {{Wiki|Xinxin Ming}} ({{Wiki|Hsin Hsin Ming}}): |

| − | At the moment of profound {{Wiki|insight}}, | + | At the [[moment]] of profound {{Wiki|insight}}, |

| − | you transcend both appearance and [[emptiness]]. | + | you transcend both [[appearance]] and [[emptiness]]. |

| − | And the 3rd [[Karmapa]] wrote in the Wishing Prayer for the {{Wiki|Attainment}} of the {{Wiki|Ultimate}} [[Mahamudra]] , | + | And the 3rd [[Karmapa]] wrote in the [[Wishing]] [[Prayer]] for the {{Wiki|Attainment}} of the {{Wiki|Ultimate}} [[Mahamudra]] , |

May we receive the flawless teachings, the foundation of which are the [[two truths]] | May we receive the flawless teachings, the foundation of which are the [[two truths]] | ||

| − | Which are free from the extremes of {{Wiki|eternalism}} and {{Wiki|nihilism}}, | + | Which are free from the [[extremes]] of {{Wiki|eternalism}} and {{Wiki|nihilism}}, |

| − | And through the supreme path of the two accumulations, free from the extremes of negation and affirmation, | + | And through the supreme [[path]] of the [[two accumulations]], free from the [[extremes]] of {{Wiki|negation}} and [[affirmation]], |

| − | May we obtain the fruit which is free from the extremes of either, | + | May we obtain the [[fruit]] which is free from the [[extremes]] of either, |

| − | Dwelling in the conditioned state or in the state of only peace. | + | Dwelling in the [[conditioned]] [[state]] or in the [[state]] of only [[peace]]. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://buddhism.about.com/od/mahayanabuddhism/a/The-Two-Truths.htm buddhism.about.com] | [http://buddhism.about.com/od/mahayanabuddhism/a/The-Two-Truths.htm buddhism.about.com] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Two Truths]] |

| + | [[Category:Barbara O'Brien]]{{BuddhismbyNumber}} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:15, 25 March 2015

By Barbara O'Brien

Two Truths

1) Relative or conventional, everyday truth of the mundane world subject to delusion and dichotomies and 2) the Ultimate Truth, transcending dichotomies, as taught by the Buddhas. According to Buddhism, there are two kinds of Truth, the Absolute and the Relative. The Absolute Truth (of the Void) manifests "illumination but is always still," and this is absolutely inexplicable. On the other hand, the Relative Truth (of the Unreal) manifests "stillness but is always illuminating," which means that it is immanent in everything. (Hsu Heng Chi/P.H. Wei).

Pure Land thinkers such as the Patriarch Tao Ch'o accepted "the legitimacy of Conventional Truth as an expression of Ultimate Truth and as a vehicle to reach Ultimate Truth. Even though all form is nonform, it is acceptable and necessary to use form within the limits of causality, because its use is an expedient means of saving others out of one's compassion for them and because, even for the unenlightened, the use of form can lead to the revelation of form as nonform" (David Chappell). Thus to reach Buddhahood, which is formless, the cultivator can practice the Pure Land method based on form.

What is reality? Dictionaries tell us that reality is "the state of things as they actually exist." In Mahayana Buddhism, reality is explained in the doctrine of the Two Truths. This doctrine tells us that existence can be understood as both ultimate and conventional (or, absolute and relative). Conventional truth is how we usually see the world, a place full of diverse and distinctive things and beings. The ultimate truth is that there are no distinctive things or beings.

To say there are no distinctive things or beings is not to say that nothing exists; it is saying that there are no distinctions. The absolute is the dharmakaya, the unity of all things and beings, unmanifested. The late Chogyam Trungpa called the dharmakaya "the basis of the original unbornness."

Confused? You are not alone. It's not an easy teaching to "get," but it's critical to understanding Mahayana Buddhism. What follows is a very basic introduction to the Two Truths.

Nagarjuna and Madhyamika

The Two Truths doctrine originated in the Madhyamika doctrine of Nagarjuna. But Nagarjuna drew this doctrine from the words of the historical Buddha as recorded in the Pali Tripitika.

In the Kaccayanagotta Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya 12.15) the Buddha said,

"By and large, Kaccayana, this world is supported by (takes as its object) a polarity, that of existence and non-existence. But when one sees the origination of the world as it actually is with right discernment, 'non-existence' with reference to the world does not occur to one. When one sees the cessation of the world as it actually is with right discernment, 'existence' with reference to the world does not occur to one."

The Buddha also taught that all phenomena manifest because of conditions created by other phenomena (dependent origination). But what are the nature of these conditioned phenomena?

An early school of Buddhism, Mahasanghika, had developed a doctrine called sunyata, which proposed that all phenomena are empty of self-essence. Nagarjuna developed sunyata further. He saw existence as a field of ever-changing conditions that cause myriad phenomena. But the myriad phenomena are empty of self-essence and take identity only in relation to other phenomena.

Echoing the words of the Buddha in the Kaccayanagotta Sutta, Nagarjuna said that one cannot truthfully say that phenomena either exist or don't exist. Madhyamika means "the middle way," and it is a middle way between negation and affirmation.

The Two Truths

Now we get to the Two Truths. Looking around us, we see distinctive phenomena. As I write this I see a cat sleeping on a chair, for example. In conventional view, the cat and the chair are two distinctive and separate phenomena.

Further, the two phenomena have many component parts. The chair is made of fabric and "stuffing" and a frame. It has a back and arms and a seat. Lily the cat has fur and limbs and whiskers and organs. These parts can be further reduced to atoms. I understand that atoms can be further reduced somehow, but I'll let the physicists sort that out.

Notice the way the English language causes us to speak of the chair and of Lily as if their component parts are attributes belonging to a self-nature. We say the chair has this and Lily has that. But the doctrine of sunyata says that these component parts are empty of self-nature; they are a temporary confluence of conditions. There is no-thing that possesses the fur or the fabric.

Further, the distinctive appearance of these phenomena -- the way we see and experience them -- is in large part created by our own nervous systems and sense organs. And the identities "chair" and "Lily" are my own projections. In other words, they are distinctive phenomena in my head, not in themselves. This distinction is conventional truth.

(I assume I appear as a distinctive phenomenon to Lily, or at least as some kind of complex of distinctive phenomena, and perhaps she projects some kind of identity onto me. At least, she doesn't seem to confuse me with the refrigerator.)

But in the absolute there are no distinctions. The absolute is described with words like boundless, pure, and perfect. And this boundless, pure perfection is as true of our existence as fabric, fur, skin, scales, feathers, or whatever the case may be.

Also the relative or conventional reality is made up of things that can be reduced to smaller things down to atomic and sub-atomic levels. Composites of composites of composites. But the absolute is not a composite.

In the Heart Sutra, we read, "Form is no other than emptiness; emptiness no other than form. Form is exactly emptiness; emptiness exactly form." The absolute is the relative, the relative is the absolute. Together, they make up reality.

Common Confusion

A couple of common ways that people misunderstand the Two Truths --

One, people sometimes create a true-false dichotomy and think that the absolute is true reality and the conventional is false reality. But remember, these are the two truths, not the one truth and one lie. Both truths are true.

Two, absolute and relative are often described as different levels of reality, but that may not be the best way to describe it. Absolute and relative are not separate; nor is one higher or lower than the other. This is a nitpicky semantic point, perhaps, but I think the word level could create a misunderstanding.

Going Beyond

Another common misunderstanding is that "enlightenment" means one has shed conventional reality and perceives only the absolute. But the sages tell us that enlightenment actually is going beyond both. The Chan patriarch Seng-ts'an (d. 606 CE) wrote in the Xinxin Ming (Hsin Hsin Ming):

At the moment of profound insight,

you transcend both appearance and emptiness.

And the 3rd Karmapa wrote in the Wishing Prayer for the Attainment of the Ultimate Mahamudra ,

May we receive the flawless teachings, the foundation of which are the two truths

Which are free from the extremes of eternalism and nihilism,

And through the supreme path of the two accumulations, free from the extremes of negation and affirmation,

May we obtain the fruit which is free from the extremes of either,

Dwelling in the conditioned state or in the state of only peace.