Difference between revisions of "Who was the most eccentric Buddhist monk of all time?"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

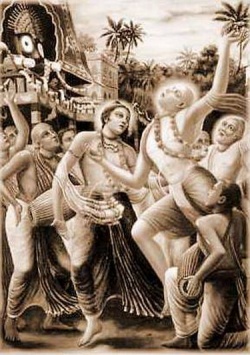

[[File:Image034.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Image034.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | This contest isn’t even close to fair. Sure, there may be many contenders - but none of them can live up to the oddball legacy of Ikkyu. Let’s cover the basics before we get to the mindboggling details, shall we? Ikkyu was born in 1394 to a low-ranking noblewoman in the court of the Japanese Emperor. That would be great, if the Emperor weren’t his dad - and his mother weren’t his dad’s mistress. The Empress didn’t much care for the fact that her husband was getting fresh with the rabble, so she had Ikkyu and his mom permanently exiled. | + | This contest isn’t even close to fair. Sure, there may be many contenders - but none of them can live up to the oddball legacy of [[Ikkyu]]. Let’s cover the basics before we get to the mindboggling details, shall we? [[Ikkyu]] was born in 1394 to a low-ranking noblewoman in the court of the [[Japanese]] [[Emperor]]. That would be great, if the [[Emperor]] weren’t his dad - and his mother weren’t his dad’s mistress. The {{Wiki|Empress}} didn’t much care for the fact that her husband was getting fresh with the rabble, so she had [[Ikkyu]] and his mom permanently exiled. |

| − | But Ikkyu persevered. Some years later, at the age of five, he was shipped off to a temple in Kyoto. This was a common practice at the time, as Buddhist temples were hotbeds of intellectual activity that offered excellent educational opportunities for precocious young children. Here in Kyoto, Ikkyu was instructed in the basic tenets and methods of Zen, and it was here that Ikkyu had his first taste of classical Chinese poetry. He soon began to write poetry of his own, a budding passion that would set him on the path to becoming history’s most eccentric Buddhist monk. | + | But [[Ikkyu]] persevered. Some years later, at the age of five, he was shipped off to a [[temple]] in {{Wiki|Kyoto}}. This was a common practice at the [[time]], as [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] were hotbeds of [[intellectual]] [[activity]] that [[offered]] {{Wiki|excellent}} educational opportunities for precocious young children. Here in {{Wiki|Kyoto}}, [[Ikkyu]] was instructed in the basic {{Wiki|tenets}} and methods of [[Zen]], and it was here that [[Ikkyu]] had his first {{Wiki|taste}} of classical {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[poetry]]. He soon began to write [[poetry]] of his own, a budding [[passion]] that would set him on the [[path]] to becoming history’s most {{Wiki|eccentric}} [[Buddhist monk]]. |

| − | Ikkyu, you see, wasn’t particularly concerned about appealing to the prevailing tastes of the time. As he matured, his poetry took a sharp turn into some seemingly unfitting territory for a Buddhist: sex and booze, primarily. Ikkyu liked to write about what he knew, and after he received inka (the certification of enlightenment), he took to the bars and the brothels in town. Kaso, his master, did not approve of Ikkyu’s newfound hobbies and swiftly grew intolerant of his association with the temple. He was asked to leave, and he complied - and so Ikkyu became the vagabond monk. | + | [[Ikkyu]], you see, wasn’t particularly concerned about appealing to the prevailing {{Wiki|tastes}} of the [[time]]. As he matured, his [[poetry]] took a sharp turn into some seemingly unfitting territory for a [[Buddhist]]: {{Wiki|sex}} and booze, primarily. [[Ikkyu]] liked to write about what he knew, and after he received [[inka]] (the certification of [[enlightenment]]), he took to the bars and the brothels in town. Kaso, his [[master]], did not approve of Ikkyu’s newfound hobbies and swiftly grew intolerant of his association with the [[temple]]. He was asked to leave, and he complied - and so [[Ikkyu]] became the vagabond [[monk]]. |

| − | He defended his drinking and love-making as legitimate paths to enlightenment, no different in practice from the sitting meditation exercised by Kaso and his disciples in the temple. He referred to this philosophy as ‘the red thread of passion,’ and he would continue to refine it throughout the course of his life. It was during these wandering years that Ikkyu met Mori, a blind singer, and fell hopelessly in love. She became the center of his universe, and his writing at the time reflects this. He recorded the most intimate details about their relationship, including some unsavory descriptions which are far too graphic to recount here. It should be noted that Ikkyu was in his eighties when Mori was nearing thirty - just chalk that up as another mark of an eccentric Buddhist monk. | + | He defended his drinking and love-making as legitimate [[paths]] to [[enlightenment]], no different in practice from the sitting [[meditation]] exercised by Kaso and his [[disciples]] in the [[temple]]. He referred to this [[philosophy]] as ‘the red thread of [[passion]],’ and he would continue to refine it throughout the course of his [[life]]. It was during these wandering years that [[Ikkyu]] met [[Mori]], a blind singer, and fell hopelessly in [[love]]. She became the center of his [[universe]], and his [[writing]] at the [[time]] reflects this. He recorded the most intimate details about their relationship, including some unsavory descriptions which are far too graphic to recount here. It should be noted that [[Ikkyu]] was in his eighties when [[Mori]] was nearing thirty - just chalk that up as another mark of an {{Wiki|eccentric}} [[Buddhist monk]]. |

| − | Ikkyu, the renegade scholar who achieved enlightenment on Lake Biwa at the age of 26, remained true to himself and his ‘red thread of | + | [[Ikkyu]], the renegade [[scholar]] who achieved [[enlightenment]] on [[Lake]] [[Biwa]] at the age of 26, remained true to himself and his ‘red thread of [[passion]]’ until his [[death]] in 1481. He is remembered today for many things: his contributions to the [[Japanese]] tea {{Wiki|ceremony}}, his unmatched talent in {{Wiki|calligraphy}}, and - of course - his bawdy and often downright dirty [[poetry]]. But perhaps his greatest [[gift]] to posterity is simply his [[idea]] that we are all free to find our own way. |

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://buddhism.yoexpert.com/buddhism-general/who-was-the-most-eccentric-buddhist-monk-of-all-ti-37973.html buddhism.yoexpert.com] | [http://buddhism.yoexpert.com/buddhism-general/who-was-the-most-eccentric-buddhist-monk-of-all-ti-37973.html buddhism.yoexpert.com] | ||

[[Category:Monks]] | [[Category:Monks]] | ||

[[Category:Japanese Buddhism]] | [[Category:Japanese Buddhism]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:18, 19 March 2014

This contest isn’t even close to fair. Sure, there may be many contenders - but none of them can live up to the oddball legacy of Ikkyu. Let’s cover the basics before we get to the mindboggling details, shall we? Ikkyu was born in 1394 to a low-ranking noblewoman in the court of the Japanese Emperor. That would be great, if the Emperor weren’t his dad - and his mother weren’t his dad’s mistress. The Empress didn’t much care for the fact that her husband was getting fresh with the rabble, so she had Ikkyu and his mom permanently exiled.

But Ikkyu persevered. Some years later, at the age of five, he was shipped off to a temple in Kyoto. This was a common practice at the time, as Buddhist temples were hotbeds of intellectual activity that offered excellent educational opportunities for precocious young children. Here in Kyoto, Ikkyu was instructed in the basic tenets and methods of Zen, and it was here that Ikkyu had his first taste of classical Chinese poetry. He soon began to write poetry of his own, a budding passion that would set him on the path to becoming history’s most eccentric Buddhist monk.

Ikkyu, you see, wasn’t particularly concerned about appealing to the prevailing tastes of the time. As he matured, his poetry took a sharp turn into some seemingly unfitting territory for a Buddhist: sex and booze, primarily. Ikkyu liked to write about what he knew, and after he received inka (the certification of enlightenment), he took to the bars and the brothels in town. Kaso, his master, did not approve of Ikkyu’s newfound hobbies and swiftly grew intolerant of his association with the temple. He was asked to leave, and he complied - and so Ikkyu became the vagabond monk.

He defended his drinking and love-making as legitimate paths to enlightenment, no different in practice from the sitting meditation exercised by Kaso and his disciples in the temple. He referred to this philosophy as ‘the red thread of passion,’ and he would continue to refine it throughout the course of his life. It was during these wandering years that Ikkyu met Mori, a blind singer, and fell hopelessly in love. She became the center of his universe, and his writing at the time reflects this. He recorded the most intimate details about their relationship, including some unsavory descriptions which are far too graphic to recount here. It should be noted that Ikkyu was in his eighties when Mori was nearing thirty - just chalk that up as another mark of an eccentric Buddhist monk.

Ikkyu, the renegade scholar who achieved enlightenment on Lake Biwa at the age of 26, remained true to himself and his ‘red thread of passion’ until his death in 1481. He is remembered today for many things: his contributions to the Japanese tea ceremony, his unmatched talent in calligraphy, and - of course - his bawdy and often downright dirty poetry. But perhaps his greatest gift to posterity is simply his idea that we are all free to find our own way.