Difference between revisions of "How Huineng Became the Sixth Patriarch"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| <poem> Shenxiu's Masterpiece Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch of Zen, is without question one of the most influential figures in Tao ...") |

m (Text replacement - "road" to "road") |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Shenxiu's Masterpiece | Shenxiu's Masterpiece | ||

| − | Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch of Zen, is without question one of the most influential figures in Tao philosophy, and this story may well be the most significant tale in Zen lore. Not only is it an interesting drama of how the underdog attained an exalted position against all prevailing expectations, but also the poetry contained herein teaches us some essential and fundamental Tao lessons. | + | [[Huineng]], the [[Sixth Patriarch]] of [[Zen]], is without question one of the most influential figures in {{Wiki|Tao}} [[philosophy]], and this story may well be the most significant tale in [[Zen]] lore. Not only is it an [[interesting]] drama of how the underdog attained an [[exalted]] position against all prevailing expectations, but also the [[poetry]] contained herein teaches us some [[essential]] and fundamental {{Wiki|Tao}} lessons. |

| − | When Huineng first came to the monastery of the Fifth Patriarch, he was a singularly unimpressive figure - a poor boy from the backward countryside who did not even know how to read or write. The learned monks at the monstery paid him to heed and in general considered him beneath contempt. Little did they realize that one day this scruffy-looking, low-class peasant would become their spiritual leader. | + | When [[Huineng]] first came to the [[monastery]] of the [[Fifth Patriarch]], he was a singularly unimpressive figure - a poor boy from the backward countryside who did not even know how to read or write. The learned [[monks]] at the monstery paid him to heed and in {{Wiki|general}} considered him beneath [[contempt]]. Little did they realize that one day this scruffy-looking, low-class peasant would become their [[spiritual]] leader. |

| − | When the time came for the Fifth Patriarch to name his successor, he ordered all the disciples to express their understanding of Zen Buddhist teachings in whatever way they saw fit. The one who could demonstrate the utmost undestanding would become the next Patriarch. | + | When the [[time]] came for the [[Fifth Patriarch]] to [[name]] his successor, he ordered all the [[disciples]] to express their [[understanding]] of [[Zen]] [[Buddhist teachings]] in whatever way they saw fit. The one who could demonstrate the utmost undestanding would become the next [[Patriarch]]. |

| − | (To understand the significance of this event, let's imagine what would happen if the Pope in Vatican should decide that his successor shall be the winner of an essay contest open to all... hmm?) | + | (To understand the significance of this event, let's [[imagine]] what would happen if the Pope in Vatican should decide that his successor shall be the winner of an essay contest open to all... hmm?) |

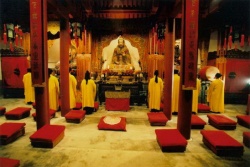

[[File:Huayan-Temple.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Huayan-Temple.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The most learned disciple at the monastery was the head monk Shenxiu, who was an accomplished scholar. Most monks felt certain that the mantle would go to him, and that there was no way any of them would be a match for Shenxiu's intellects. Many did not even try. | + | The most learned [[disciple]] at the [[monastery]] was the {{Wiki|head}} [[monk]] [[Shenxiu]], who was an accomplished [[scholar]]. Most [[monks]] felt certain that the mantle would go to him, and that there was no way any of them would be a match for Shenxiu's intellects. Many did not even try. |

| − | To demonstrate his wisdom, Shenxiu wrote his famous poem on the wall of a temple corridor: | + | To demonstrate his [[wisdom]], [[Shenxiu]] wrote his famous poem on the wall of a [[temple]] corridor: |

| − | Body is the bodhi tree | + | [[Body]] is the [[bodhi tree]] |

| − | Heart is like clear mirror stand | + | [[Heart]] is like clear [[mirror]] stand |

Strive to clean it constantly | Strive to clean it constantly | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Do not let the dust motes land | Do not let the dust motes land | ||

| − | (If you know Chinese, you may notice that the above is a poetic translation rather than a rigorously exact one. If you're wondering how I arrived at the above, take a look at the Translation Notes.) | + | (If you know {{Wiki|Chinese}}, you may [[notice]] that the above is a poetic translation rather than a rigorously exact one. If you're wondering how I arrived at the above, take a look at the Translation Notes.) |

| − | Bodhi means enlightenment or spiritual awakening. The bodhi tree is the tree that Gautama sat under when he became fully enlightened and attained the state of grace known as Buddhahood. This type of tree originally grew on the banks of a tributary of the Ganges and features heart-shaped leaves. | + | [[Bodhi]] means [[enlightenment]] or [[spiritual]] [[awakening]]. The [[bodhi tree]] is the [[tree]] that [[Gautama]] sat under when he became [[fully enlightened]] and attained the state of grace known as [[Buddhahood]]. This type of [[tree]] originally grew on the banks of a tributary of the [[Ganges]] and {{Wiki|features}} heart-shaped leaves. |

[[File:Huayan-t012.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Huayan-t012.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | In his poem Shenxiu compares the human body to the bodhi tree. His meaning is that sitting by the tree is the human soul, which like Gautama, is capable of attaining the ultimate wisdom. | + | In his poem [[Shenxiu]] compares the [[human]] [[body]] to the [[bodhi tree]]. His [[meaning]] is that sitting by the [[tree]] is the [[human]] [[soul]], which like [[Gautama]], is capable of [[attaining]] the [[ultimate]] [[wisdom]]. |

| − | (Incidentally, The Bodhi Tree is also the name of the famous bookstore on Melrose devoted to metaphysical subjects. An interesting fact about the bookstore is that it was founded by, of all people, three aerospace engineers! That's perhaps a compelling testimonial that not all engineers are the stereotypical cardboard figures.) | + | (Incidentally, The [[Bodhi Tree]] is also the [[name]] of the famous bookstore on Melrose devoted to [[metaphysical]] [[subjects]]. An [[interesting]] fact about the bookstore is that it was founded by, of all [[people]], three aerospace engineers! That's perhaps a compelling testimonial that not all engineers are the stereotypical cardboard figures.) |

| − | Also, in his poem Shenxiu compares the soul to a mirror that must be kept clean at all times. The "dust" in the poem refers to all the distractions, temptations and impure thoughts of the material world. To keep the soul clear of these unclean elements, a Zen disciple must diligently practice Tao - which is to say, engage in pursuits such as meditation, reading and reciting of scriptures, and the performance of the various rituals. | + | Also, in his poem [[Shenxiu]] compares the [[soul]] to a [[mirror]] that must be kept clean at all times. The "dust" in the poem refers to all the distractions, temptations and [[impure]] [[thoughts]] of the {{Wiki|material}} [[world]]. To keep the [[soul]] clear of these unclean [[elements]], a [[Zen]] [[disciple]] must diligently practice {{Wiki|Tao}} - which is to say, engage in pursuits such as [[meditation]], reading and reciting of [[scriptures]], and the performance of the various [[rituals]]. |

| − | In a nutshell, Shenxiu expresses that the road of enlightenment is not an easy one. Only through hard work and never-ending diligence can one purify one's mind sufficiently to attain Buddhahood. The poem was a rallying call for the monks to fortify their resolve as they continue on this difficult spiritual journey. | + | In a nutshell, [[Shenxiu]] expresses that the road of [[enlightenment]] is not an easy one. Only through hard work and never-ending [[diligence]] can one {{Wiki|purify}} one's [[mind]] sufficiently to attain [[Buddhahood]]. The poem was a rallying call for the [[monks]] to fortify their resolve as they continue on this difficult [[spiritual]] journey. |

| − | All the monks were impressed. And, certain that this poem is effectively the edict from their next leader, they all memorized it and recited it as they went about their daily duties. Huineng overheard them, and that was how he learned of the existence of Shenxiu's work. | + | All the [[monks]] were impressed. And, certain that this poem is effectively the edict from their next leader, they all memorized it and recited it as they went about their daily duties. [[Huineng]] overheard them, and that was how he learned of the [[existence]] of Shenxiu's work. |

| − | (Now let's think about this for a moment. How would you top Shenxiu if you were Huineng? Shenxiu's poem seems impeccable! Who can fault this declaration of a cultivator's total commitment to constant effort to achieve the ultimate enlightenment?) | + | (Now let's think about this for a moment. How would you top [[Shenxiu]] if you were [[Huineng]]? Shenxiu's poem seems impeccable! Who can fault this declaration of a cultivator's total commitment to [[constant]] [[effort]] to achieve the [[ultimate]] [[enlightenment]]?) |

[[File:Imag 1417.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Imag 1417.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

Huineng's Response | Huineng's Response | ||

| − | Huineng understood instantly where Shenxiu fell short. There was another level of wisdom beyond that described in Shenxiu's poem. Huineng knew how to express this understanding in a poem - but being illiterate, did not know how to write it down. He ended up asking another monk to write it up on the same wall for him: | + | [[Huineng]] understood instantly where [[Shenxiu]] fell short. There was another level of [[wisdom]] [[beyond]] that described in Shenxiu's poem. [[Huineng]] knew how to express this [[understanding]] in a poem - but {{Wiki|being}} illiterate, did not know how to write it down. He ended up asking another [[monk]] to write it up on the same wall for him: |

| − | Bodhi really has no tree | + | [[Bodhi]] really has no [[tree]] |

| − | Nor is clear mirror the stand | + | Nor is clear [[mirror]] the stand |

Nothing's there initially | Nothing's there initially | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

So where can the dust motes land? | So where can the dust motes land? | ||

[[File:Ksitigarbha-es32.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Ksitigarbha-es32.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | When they saw this poetic response, the monks did not get it at all. But the Fifth Patriarch comprehended Huineng's meaning perfectly. Represented in these four lines was an intuitive mind more capable of grasping fundamental Tao concepts than Shenxiu's formidable intellect after decades of schooling. | + | When they saw this poetic response, the [[monks]] did not get it at all. But the [[Fifth Patriarch]] comprehended Huineng's [[meaning]] perfectly. Represented in these four lines was an intuitive [[mind]] more capable of [[grasping]] fundamental {{Wiki|Tao}} concepts than Shenxiu's formidable {{Wiki|intellect}} after decades of schooling. |

| − | Now, if the Fifth Patriarch were to announce Huineng's succession publicly and hand the reins over to him, he knew that the monks would not understand. They probably would turn on Huineng and possibly even cause him harm just to prevent him from assuming the office. Therefore, he pretended to be unimpressed with the response. In great secrecy, and in the middle of the night, he passed the symbol of his authority - a bowl and a robe - to Huineng and ordered him to flee for his life. | + | Now, if the [[Fifth Patriarch]] were to announce Huineng's succession publicly and hand the reins over to him, he knew that the [[monks]] would not understand. They probably would turn on [[Huineng]] and possibly even [[cause]] him {{Wiki|harm}} just to prevent him from assuming the office. Therefore, he pretended to be unimpressed with the response. In great secrecy, and in the middle of the night, he passed the [[symbol]] of his authority - a [[bowl]] and a robe - to [[Huineng]] and ordered him to flee for his [[life]]. |

| − | And so Huineng did hastily depart the monastery, with a mob of angry monks in hot pursuit. What happenned after that is another story for another time. For now, let us ask this question: what exactly was the meaning of Huineng's poem that impressed his master so much? | + | And so [[Huineng]] did hastily depart the [[monastery]], with a mob of [[angry]] [[monks]] in [[hot]] pursuit. What happenned after that is another story for another [[time]]. For now, let us ask this question: what exactly was the [[meaning]] of Huineng's poem that impressed his [[master]] so much? |

| − | Huineng's central insight is in pointing out the transient or "illusory" nature of the physical world. "Bodhi has no tree," he said. Why not? Because our immortal souls are an entity apart from the physical bodies we inhabit temporarily. Wisdom, awakening and enlightenment are the attributes of this immaterial spirit, and exist with or without the body. | + | Huineng's {{Wiki|central}} [[insight]] is in pointing out the transient or "[[illusory]]" nature of the [[physical]] [[world]]. "[[Bodhi]] has no [[tree]]," he said. Why not? Because our [[immortal]] [[souls]] are an {{Wiki|entity}} apart from the [[physical]] [[bodies]] we inhabit temporarily. [[Wisdom]], [[awakening]] and [[enlightenment]] are the attributes of this {{Wiki|immaterial}} [[spirit]], and [[exist]] with or without the [[body]]. |

| − | "Clear mirror" isn't the stand. Why not? Remember that Shenxiu compared the heart to the stand, which holds the soul - the mirror - in place. Huineng points out that this is but an artificial constraint. The soul is there whether or not there's anything holding it up. The heart - the stand - isn't required or even particularly important! | + | "Clear [[mirror]]" isn't the stand. Why not? Remember that [[Shenxiu]] compared the [[heart]] to the stand, which holds the [[soul]] - the [[mirror]] - in place. [[Huineng]] points out that this is but an artificial constraint. The [[soul]] is there whether or not there's anything [[holding]] it up. The [[heart]] - the stand - isn't required or even particularly important! |

| − | Huineng further points out that all the defilements and distortions of the material world are just as transient or illusory as these temporary mortal forms we assume. The polluting influences of the physical world come and go and cannot last, unlike the immortal soul. In other words, our essential, eternal selves are the only real entities in the universe. Money, material possessions, fineries, precious jewels... none of these are things we can take with us when we pass beyond. For all practical intents and purposes, they may as well not exist! | + | [[Huineng]] further points out that all the [[defilements]] and distortions of the {{Wiki|material}} [[world]] are just as transient or [[illusory]] as these temporary {{Wiki|mortal}} [[forms]] we assume. The polluting [[influences]] of the [[physical]] [[world]] come and go and cannot last, unlike the [[immortal]] [[soul]]. In other words, our [[essential]], [[eternal]] selves are the only {{Wiki|real}} entities in the [[universe]]. [[Money]], {{Wiki|material}} {{Wiki|possessions}}, fineries, [[precious]] jewels... none of these are things we can take with us when we pass [[beyond]]. For all practical intents and purposes, they may as well not [[exist]]! |

| − | If one can completely come to grips with this basic truth expressed by Huineng (easier said than done... you still wanna win the Lotto and you know it), enlightenment can happen in an instant. Hence, the true path to Buddhahood isn't the direction of hard work and the acquisition of even more knowledge and scriptures, as indicated by Shenxiu. The truer path is along the road of intuitive insight, where we progress beyond mere logic and reasoning and become one with wisdom and understanding. | + | If one can completely come to grips with this basic [[truth]] expressed by [[Huineng]] (easier said than done... you still wanna win the Lotto and you know it), [[enlightenment]] can happen in an instant. Hence, the true [[path]] to [[Buddhahood]] isn't the [[direction]] of hard work and the acquisition of even more [[knowledge]] and [[scriptures]], as indicated by [[Shenxiu]]. The truer [[path]] is along the road of intuitive [[insight]], where we progress [[beyond]] mere [[logic]] and {{Wiki|reasoning}} and become one with [[wisdom]] and [[understanding]]. |

| − | How can we traverse this path? With our entire being, rather than just one hemisphere of the brain. Too much intellectual sophistry leads nowhere except ever more confusing and confounding complexity. It's time we recognize the fundamentals and come to the simple yet profound realization that, hey, all this Tao and Zen stuff ain't the mystical, mysterious stuff that only inscrutible Orientals can understand! When you get right down to it, the ancient masters and sages are really trying to tell us to stick to the basics and keep it simple. Simplicity and clarifying, penetrating basic truths - these are the essence of Tao and this is the golden nugget of knowledge we have come all this way to find. | + | How can we traverse this [[path]]? With our entire {{Wiki|being}}, rather than just one hemisphere of the [[brain]]. Too much [[intellectual]] sophistry leads nowhere except ever more confusing and confounding complexity. It's [[time]] we [[recognize]] the fundamentals and come to the simple yet profound [[realization]] that, hey, all this {{Wiki|Tao}} and [[Zen]] stuff ain't the [[mystical]], mysterious stuff that only inscrutible Orientals can understand! When you get right down to it, the {{Wiki|ancient}} [[masters]] and [[sages]] are really trying to tell us to stick to the basics and keep it simple. [[Simplicity]] and clarifying, penetrating basic [[truths]] - these are the [[essence]] of {{Wiki|Tao}} and this is the golden nugget of [[knowledge]] we have come all this way to find. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://www.taoism.net/stories/6patri.htm www.taoism.net] | [http://www.taoism.net/stories/6patri.htm www.taoism.net] | ||

[[Category:Huineng]] | [[Category:Huineng]] | ||

Latest revision as of 04:30, 9 February 2016

Shenxiu's Masterpiece

Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch of Zen, is without question one of the most influential figures in Tao philosophy, and this story may well be the most significant tale in Zen lore. Not only is it an interesting drama of how the underdog attained an exalted position against all prevailing expectations, but also the poetry contained herein teaches us some essential and fundamental Tao lessons.

When Huineng first came to the monastery of the Fifth Patriarch, he was a singularly unimpressive figure - a poor boy from the backward countryside who did not even know how to read or write. The learned monks at the monstery paid him to heed and in general considered him beneath contempt. Little did they realize that one day this scruffy-looking, low-class peasant would become their spiritual leader.

When the time came for the Fifth Patriarch to name his successor, he ordered all the disciples to express their understanding of Zen Buddhist teachings in whatever way they saw fit. The one who could demonstrate the utmost undestanding would become the next Patriarch.

(To understand the significance of this event, let's imagine what would happen if the Pope in Vatican should decide that his successor shall be the winner of an essay contest open to all... hmm?)

The most learned disciple at the monastery was the head monk Shenxiu, who was an accomplished scholar. Most monks felt certain that the mantle would go to him, and that there was no way any of them would be a match for Shenxiu's intellects. Many did not even try.

To demonstrate his wisdom, Shenxiu wrote his famous poem on the wall of a temple corridor:

Body is the bodhi tree

Heart is like clear mirror stand

Strive to clean it constantly

Do not let the dust motes land

(If you know Chinese, you may notice that the above is a poetic translation rather than a rigorously exact one. If you're wondering how I arrived at the above, take a look at the Translation Notes.)

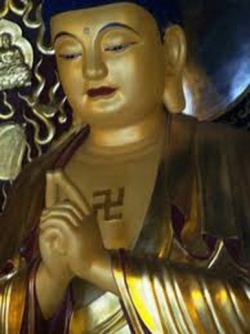

Bodhi means enlightenment or spiritual awakening. The bodhi tree is the tree that Gautama sat under when he became fully enlightened and attained the state of grace known as Buddhahood. This type of tree originally grew on the banks of a tributary of the Ganges and features heart-shaped leaves.

In his poem Shenxiu compares the human body to the bodhi tree. His meaning is that sitting by the tree is the human soul, which like Gautama, is capable of attaining the ultimate wisdom.

(Incidentally, The Bodhi Tree is also the name of the famous bookstore on Melrose devoted to metaphysical subjects. An interesting fact about the bookstore is that it was founded by, of all people, three aerospace engineers! That's perhaps a compelling testimonial that not all engineers are the stereotypical cardboard figures.)

Also, in his poem Shenxiu compares the soul to a mirror that must be kept clean at all times. The "dust" in the poem refers to all the distractions, temptations and impure thoughts of the material world. To keep the soul clear of these unclean elements, a Zen disciple must diligently practice Tao - which is to say, engage in pursuits such as meditation, reading and reciting of scriptures, and the performance of the various rituals.

In a nutshell, Shenxiu expresses that the road of enlightenment is not an easy one. Only through hard work and never-ending diligence can one purify one's mind sufficiently to attain Buddhahood. The poem was a rallying call for the monks to fortify their resolve as they continue on this difficult spiritual journey.

All the monks were impressed. And, certain that this poem is effectively the edict from their next leader, they all memorized it and recited it as they went about their daily duties. Huineng overheard them, and that was how he learned of the existence of Shenxiu's work.

(Now let's think about this for a moment. How would you top Shenxiu if you were Huineng? Shenxiu's poem seems impeccable! Who can fault this declaration of a cultivator's total commitment to constant effort to achieve the ultimate enlightenment?)

Huineng's Response

Huineng understood instantly where Shenxiu fell short. There was another level of wisdom beyond that described in Shenxiu's poem. Huineng knew how to express this understanding in a poem - but being illiterate, did not know how to write it down. He ended up asking another monk to write it up on the same wall for him:

Bodhi really has no tree

Nor is clear mirror the stand

Nothing's there initially

So where can the dust motes land?

When they saw this poetic response, the monks did not get it at all. But the Fifth Patriarch comprehended Huineng's meaning perfectly. Represented in these four lines was an intuitive mind more capable of grasping fundamental Tao concepts than Shenxiu's formidable intellect after decades of schooling.

Now, if the Fifth Patriarch were to announce Huineng's succession publicly and hand the reins over to him, he knew that the monks would not understand. They probably would turn on Huineng and possibly even cause him harm just to prevent him from assuming the office. Therefore, he pretended to be unimpressed with the response. In great secrecy, and in the middle of the night, he passed the symbol of his authority - a bowl and a robe - to Huineng and ordered him to flee for his life.

And so Huineng did hastily depart the monastery, with a mob of angry monks in hot pursuit. What happenned after that is another story for another time. For now, let us ask this question: what exactly was the meaning of Huineng's poem that impressed his master so much?

Huineng's central insight is in pointing out the transient or "illusory" nature of the physical world. "Bodhi has no tree," he said. Why not? Because our immortal souls are an entity apart from the physical bodies we inhabit temporarily. Wisdom, awakening and enlightenment are the attributes of this immaterial spirit, and exist with or without the body.

"Clear mirror" isn't the stand. Why not? Remember that Shenxiu compared the heart to the stand, which holds the soul - the mirror - in place. Huineng points out that this is but an artificial constraint. The soul is there whether or not there's anything holding it up. The heart - the stand - isn't required or even particularly important!

Huineng further points out that all the defilements and distortions of the material world are just as transient or illusory as these temporary mortal forms we assume. The polluting influences of the physical world come and go and cannot last, unlike the immortal soul. In other words, our essential, eternal selves are the only real entities in the universe. Money, material possessions, fineries, precious jewels... none of these are things we can take with us when we pass beyond. For all practical intents and purposes, they may as well not exist!

If one can completely come to grips with this basic truth expressed by Huineng (easier said than done... you still wanna win the Lotto and you know it), enlightenment can happen in an instant. Hence, the true path to Buddhahood isn't the direction of hard work and the acquisition of even more knowledge and scriptures, as indicated by Shenxiu. The truer path is along the road of intuitive insight, where we progress beyond mere logic and reasoning and become one with wisdom and understanding.

How can we traverse this path? With our entire being, rather than just one hemisphere of the brain. Too much intellectual sophistry leads nowhere except ever more confusing and confounding complexity. It's time we recognize the fundamentals and come to the simple yet profound realization that, hey, all this Tao and Zen stuff ain't the mystical, mysterious stuff that only inscrutible Orientals can understand! When you get right down to it, the ancient masters and sages are really trying to tell us to stick to the basics and keep it simple. Simplicity and clarifying, penetrating basic truths - these are the essence of Tao and this is the golden nugget of knowledge we have come all this way to find.