Difference between revisions of "Khaggavisāna-sutta"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| The Rhinoceros Sutra has long been identified, along with the Aṭṭhakavagga and Pārāyanavagga as one of the earliest texts fo...") |

|||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Efault.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Efault.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The [[Rhinoceros Sutra]] has long been identified, along with the [[Aṭṭhakavagga]] and [[Pārāyanavagga]] as one of the earliest texts found in the [[Pali Canon]]. (Salomon, pp. 15-16) This identification has been reinforced by the discovery of a version in the {{Wiki|Gandharan Buddhist Texts}}, the oldest [[Buddhist]] (and, indeed, {{Wiki|Indian}}) {{Wiki|manuscripts}} extant. It also exists in a {{Wiki|Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit}} version. The early date for the text along with its rather unusual (within community-oriented [[Buddhism]]) approach to {{Wiki|monastic}} life have led some {{Wiki|scholars}} to suggest that it represents a holdover from a very early stage of [[Buddhism]]. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Rhinoceros Sutra]] has long been identified, along with the [[Aṭṭhakavagga]] and [[Pārāyanavagga]] as one of the earliest texts found in the [[Pali Canon]]. (Salomon, pp. 15-16) This identification has been reinforced by the discovery of a version in the {{Wiki|Gandharan Buddhist Texts}}, the oldest [[Buddhist]] (and, indeed, {{Wiki|Indian}}) {{Wiki|manuscripts}} extant. It also [[exists]] in a {{Wiki|Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit}} version. The early date for the text along with its rather unusual (within community-oriented [[Buddhism]]) approach to {{Wiki|monastic}} [[life]] have led some {{Wiki|scholars}} to suggest that it represents a holdover from a very early stage of [[Buddhism]]. | ||

Themes | Themes | ||

| − | The [[sutra]], which consists of a series of verses which discuss both the perils of community life and the benefits of solitude, and almost all of which end with the admonition that seekers should wander alone like rhinoceros. The verses are somewhat variable between versions, as is the ordering of verses, suggesting a rich oral tradition that diverged regionally or by sect before being written down. | + | The [[sutra]], which consists of a series of verses which discuss both the perils of {{Wiki|community}} [[life]] and the benefits of [[solitude]], and almost all of which end with the admonition that seekers should wander alone like [[rhinoceros]]. The verses are somewhat variable between versions, as is the ordering of verses, suggesting a rich [[oral tradition]] that diverged regionally or by [[sect]] before being written down. |

Association with [[pratyekabuddhas]] | Association with [[pratyekabuddhas]] | ||

| − | Traditional commentaries on the text have unanimously associated the [[Rhinoceros Sutra]] with the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] of [[pratyekabuddhas]]. (Salomon, p. 10, 13) | + | [[Traditional]] commentaries on the text have unanimously associated the [[Rhinoceros Sutra]] with the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] of [[pratyekabuddhas]]. (Salomon, p. 10, 13) |

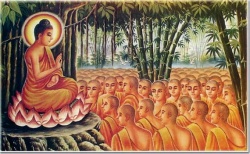

[[File:Day-of-makha-bucha 1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Day-of-makha-bucha 1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | In the 4th century [[Mahāyāna]] [[abhidharma]] work [[Abhidharmasamuccaya]], [[Asaṅga]] describes followers of the [[Pratyekabuddha Vehicle]] (Skt. [[pratyekabuddhayanika]]) as those who dwell alone like the horn of a rhinoceros, or as a [[solitary conquerors]] (Skt. [[pratyekajina]]) living in a small group. Here they are characterized as utilizing the same canon of texts as the [[śrāvakas]], the [[Śrāvaka Piṭaka]], but having a different set of teachings, the [[Pratyekabuddha]] [[Dharma]]. | + | In the 4th century [[Mahāyāna]] [[abhidharma]] work [[Abhidharmasamuccaya]], [[Asaṅga]] describes followers of the [[Pratyekabuddha Vehicle]] (Skt. [[pratyekabuddhayanika]]) as those who dwell alone like the horn of a [[rhinoceros]], or as a [[solitary conquerors]] (Skt. [[pratyekajina]]) living in a small group. Here they are characterized as utilizing the same [[canon]] of texts as the [[śrāvakas]], the [[Śrāvaka Piṭaka]], but having a different set of teachings, the [[Pratyekabuddha]] [[Dharma]]. |

| − | Naming controversy | + | Naming [[controversy]] |

| − | There is an ongoing dispute over whether the title, "sword-horn" [[sutra]], is to be taken as a [[tatpuruṣa]] compound (a sword which is a horn) or as a [[bahuvrīhi]] compound (one who has a sword as a horn). In the former case, the title should be rendered "[[The Rhinoceros-Horn Sutra]]"; in the latter case, it should be rendered, "[[The Rhinoceros Sutra]]." There is textual evidence to support either interpretation. (Salomon, pp. 11-12) | + | There is an ongoing dispute over whether the title, "sword-horn" [[sutra]], is to be taken as a [[tatpuruṣa]] compound (a sword which is a horn) or as a [[bahuvrīhi]] compound (one who has a sword as a horn). In the former case, the title should be rendered "[[The Rhinoceros-Horn Sutra]]"; in the [[latter]] case, it should be rendered, "[[The Rhinoceros Sutra]]." There is textual {{Wiki|evidence}} to support either [[interpretation]]. (Salomon, pp. 11-12) |

| − | In general, the [[Mahāyāna]] [[traditions]] in {{Wiki|India}} took the title to refer to the image of an Indian rhinoceros, which is a solitary animal. The [[Theravāda]] [[tradition]] tended toward the "rhinoceros horn" interpretation, but there is some variance between [[Theravāda]] commentators, with some referring to the image of a rhinoceros rather than a rhinoceros horn. (Salomon, p. 13) | + | In general, the [[Mahāyāna]] [[traditions]] in {{Wiki|India}} took the title to refer to the image of an [[Indian]] [[rhinoceros]], which is a {{Wiki|solitary}} [[animal]]. The [[Theravāda]] [[tradition]] tended toward the "[[rhinoceros]] horn" [[interpretation]], but there is some variance between [[Theravāda]] commentators, with some referring to the image of a [[rhinoceros]] rather than a [[rhinoceros]] horn. (Salomon, p. 13) |

Location in [[Buddhist]] canons | Location in [[Buddhist]] canons | ||

| − | In the [[Pali]] [[Suttapitaka]], this [[sutta]] is the third [[sutta]] in the [[Khuddaka Nikaya]]'s [[Sutta Nipata]]'s first chapter ([[Uragavagga]], or the "[[Snake Chapter]]," named after the chapter's first [[sutta]]), and thus can be referenced in the [[Pali canon]] as "Sn 1.3." For a complete translation of the [[Pali]] text, see Thanissaro (1997). | + | In the [[Pali]] [[Suttapitaka]], this [[sutta]] is the third [[sutta]] in the [[Khuddaka Nikaya]]'s [[Sutta Nipata]]'s first [[chapter]] ([[Uragavagga]], or the "[[Snake Chapter]]," named after the chapter's first [[sutta]]), and thus can be referenced in the [[Pali canon]] as "Sn 1.3." For a complete translation of the [[Pali]] text, see [[Thanissaro]] (1997). |

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

[[Category:Khaggavisāna-sutta]] | [[Category:Khaggavisāna-sutta]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:16, 13 July 2024

The Rhinoceros Sutra has long been identified, along with the Aṭṭhakavagga and Pārāyanavagga as one of the earliest texts found in the Pali Canon. (Salomon, pp. 15-16) This identification has been reinforced by the discovery of a version in the Gandharan Buddhist Texts, the oldest Buddhist (and, indeed, Indian) manuscripts extant. It also exists in a Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit version. The early date for the text along with its rather unusual (within community-oriented Buddhism) approach to monastic life have led some scholars to suggest that it represents a holdover from a very early stage of Buddhism.

Themes

The sutra, which consists of a series of verses which discuss both the perils of community life and the benefits of solitude, and almost all of which end with the admonition that seekers should wander alone like rhinoceros. The verses are somewhat variable between versions, as is the ordering of verses, suggesting a rich oral tradition that diverged regionally or by sect before being written down. Association with pratyekabuddhas

Traditional commentaries on the text have unanimously associated the Rhinoceros Sutra with the Buddhist tradition of pratyekabuddhas. (Salomon, p. 10, 13)

In the 4th century Mahāyāna abhidharma work Abhidharmasamuccaya, Asaṅga describes followers of the Pratyekabuddha Vehicle (Skt. pratyekabuddhayanika) as those who dwell alone like the horn of a rhinoceros, or as a solitary conquerors (Skt. pratyekajina) living in a small group. Here they are characterized as utilizing the same canon of texts as the śrāvakas, the Śrāvaka Piṭaka, but having a different set of teachings, the Pratyekabuddha Dharma. Naming controversy

There is an ongoing dispute over whether the title, "sword-horn" sutra, is to be taken as a tatpuruṣa compound (a sword which is a horn) or as a bahuvrīhi compound (one who has a sword as a horn). In the former case, the title should be rendered "The Rhinoceros-Horn Sutra"; in the latter case, it should be rendered, "The Rhinoceros Sutra." There is textual evidence to support either interpretation. (Salomon, pp. 11-12)

In general, the Mahāyāna traditions in India took the title to refer to the image of an Indian rhinoceros, which is a solitary animal. The Theravāda tradition tended toward the "rhinoceros horn" interpretation, but there is some variance between Theravāda commentators, with some referring to the image of a rhinoceros rather than a rhinoceros horn. (Salomon, p. 13) Location in Buddhist canons

In the Pali Suttapitaka, this sutta is the third sutta in the Khuddaka Nikaya's Sutta Nipata's first chapter (Uragavagga, or the "Snake Chapter," named after the chapter's first sutta), and thus can be referenced in the Pali canon as "Sn 1.3." For a complete translation of the Pali text, see Thanissaro (1997).