Difference between revisions of "Asaṅga"

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

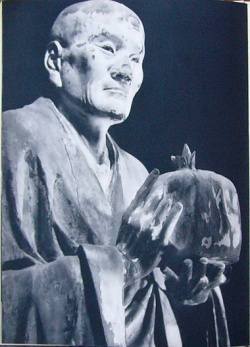

[[File:Asanga013.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Asanga013.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | [[Asaṅga]] ([[Sanskrit]]: असङ्ग; [[Tibetan]]: | + | [[Asaṅga]] ([[Sanskrit]]: [[असङ्ग]]; [[Tibetan]]: {{BigTibetan|[[ཐོགས་མེད]]}}{{BigTibetan|།}}; [[Wylie]]: [[Thogs med]]; [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Chinese}}: [[無著]]; pinyin: [[Wúzhuó]]; [[Romaji]]: [[Mujaku]]) was a major exponent of the [[Yogācāra]] [[tradition]] in [[India]], also called [[Vijñānavāda]]. [[Traditionally]], he and his half-brother [[Vasubandhu]] are regarded as the founders of this school. The two half-brothers were also major exponents of [[Abhidharma]] teachings, which were highly technical and sophisticated {{Wiki|hermeneutics}} as well. |

Early [[life]] | Early [[life]] | ||

| − | [[Asaṅga]] was born as the son of a [[Kṣatriya]] father and [[Brahmin]] mother in Puruṣapura (present day Peshawar in {{Wiki|Pakistan}}), which at that time was part of the ancient kingdom of [[Gandhāra]]. Current scholarship places him in the fourth century CE. He was perhaps originally a member of the [[Mahīśāsaka]] school or the Mūlasarvāstivāda school but later converted to [[Mahāyāna]]. According to some [[scholars]], Asaṅga's frameworks for [[abhidharma]] writings retained many underlying [[Mahīśāsaka]] traits. André Bareau writes: | + | [[Asaṅga]] was born as the son of a [[Kṣatriya]] father and [[Brahmin]] mother in [[Puruṣapura]] ({{Wiki|present}} day {{Wiki|Peshawar}} in {{Wiki|Pakistan}}), which at that [[time]] was part of the {{Wiki|ancient}} {{Wiki|kingdom}} of [[Gandhāra]]. Current {{Wiki|scholarship}} places him in [[the fourth]] century CE. He was perhaps originally a member of the [[Mahīśāsaka]] school or the [[Mūlasarvāstivāda school]] but later converted to [[Mahāyāna]]. According to some [[scholars]], [[Asaṅga's]] frameworks for [[abhidharma]] writings retained many underlying [[Mahīśāsaka]] traits. [[André Bareau]] writes: |

| − | [It is] sufficiently obvious that [[Asaṅga]] had been a [[Mahīśāsaka]] when he was a young [[monk]], and that he incorporated a large part of the doctrinal opinions proper to this school within his own work after he became a [[great master]] of the [[Mahāyāna]], when he made up what can be considered as a new and [[Mahāyānist]] [[Abhidharma-piṭaka]]. | + | [It is] sufficiently obvious that [[Asaṅga]] had been a [[Mahīśāsaka]] when he was a young [[monk]], and that he incorporated a large part of the [[doctrinal]] opinions proper to this school within his [[own]] work after he became a [[great master]] of the [[Mahāyāna]], when he made up what can be considered as a new and [[Mahāyānist]] [[Abhidharma-piṭaka]]. |

| − | In the record of his journeys through the kingdoms of [[India]], [[Xuanzang]] wrote that [[Asaṅga]] was initially a [[Mahīśāsaka]] [[monk]], but soon turned toward the [[Mahāyāna]] teachings. [[Asaṅga]] had a half-brother, [[Vasubandhu]], who was a [[monk]] from the [[Sarvāstivāda]] school. [[Vasubandhu]] is said to have taken up [[Mahāyāna Buddhism]] after meeting with [[Asaṅga]] and one of Asaṅga's [[disciples]]. | + | In the record of his journeys through the {{Wiki|kingdoms}} of [[India]], [[Xuanzang]] wrote that [[Asaṅga]] was initially a [[Mahīśāsaka]] [[monk]], but soon turned toward the [[Mahāyāna]] teachings. [[Asaṅga]] had a half-brother, [[Vasubandhu]], who was a [[monk]] from the [[Sarvāstivāda]] school. [[Vasubandhu]] is said to have taken up [[Mahāyāna Buddhism]] after meeting with [[Asaṅga]] and one of [[Asaṅga's]] [[disciples]]. |

[[Meditation]] and teachings | [[Meditation]] and teachings | ||

| − | [[Asaṅga]] spent many years in serious [[meditation]], during which time [[tradition]] says that he often visited [[Tuṣita]] [[Heaven]] to receive teachings from [[Maitreya]] [[Bodhisattva]]. [[Heavens]] such as [[Tuṣita]] [[Heaven]] is said to be accessible through [[meditation]], and accounts of this are given in the writings of the [[Indian]] [[Buddhist monk]] [[Paramārtha]], who lived during the 6th century CE. [[Xuanzang]] tells a similar account of these events: | + | [[Asaṅga]] spent many years in serious [[meditation]], during which [[time]] [[tradition]] says that he often visited [[Tuṣita]] [[Heaven]] to receive teachings from [[Maitreya]] [[Bodhisattva]]. [[Heavens]] such as [[Tuṣita]] [[Heaven]] is said to be accessible through [[meditation]], and accounts of this are given in the writings of the [[Indian]] [[Buddhist monk]] [[Paramārtha]], who lived during the 6th century CE. [[Xuanzang]] tells a similar account of these events: |

| − | In the great mango grove five or six li to the southwest of the city ([[Ayodhya]]), there is an old [[monastery]] where [[Asaṅga]] [[Bodhisattva]] received instructions and guided the common [[people]]. At night he went up to the place of [[Maitreya]] [[Bodhisattva]] in [[Tuṣita]] [[Heaven]] to learn the [[Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra]], the Mahāyāna-sūtra-alaṃkāra-śāstra, the Madhyānta-vibhāga-śāstra, etc.; in the daytime, he lectured on the marvelous principles to a great audience. | + | In the great [[mango grove]] five or six li to the [[southwest]] of the city ([[Ayodhya]]), there is an old [[monastery]] where [[Asaṅga]] [[Bodhisattva]] received instructions and guided the common [[people]]. At night he went up to the place of [[Maitreya]] [[Bodhisattva]] in [[Tuṣita]] [[Heaven]] to learn the [[Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra]], the [[Mahāyāna-sūtra-alaṃkāra-śāstra]], the [[Madhyānta-vibhāga-śāstra]], etc.; in the daytime, he lectured on the marvelous {{Wiki|principles}} to a great audience. |

| − | [[Asaṅga]] went on to write many of the key [[Yogācāra]] treatises such as the [[Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra]], the Mahāyāna-samgraha and the [[Abhidharma-samuccaya]] as well as other works, although there are discrepancies between the {{Wiki|Chinese}} and [[Tibetan]] [[traditions]] concerning which works are attributed to him and which to [[Maitreya]]. | + | [[Asaṅga]] went on to write many of the key [[Yogācāra]] treatises such as the [[Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra]], the [[Mahāyāna-samgraha]] and the [[Abhidharma-samuccaya]] as well as other works, although there are discrepancies between the {{Wiki|Chinese}} and [[Tibetan]] [[traditions]] concerning which works are attributed to him and which to [[Maitreya]]. |

| − | [[Abhidharma]] | + | [[Abhidharma Samuccaya]] |

Main article: [[Abhidharma-samuccaya]] | Main article: [[Abhidharma-samuccaya]] | ||

| Line 23: | Line 32: | ||

Questions of authorship | Questions of authorship | ||

| − | The [[Tibetan tradition]] attributes authorship of the Ratnagotravibhaga to him, while the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[traditions]] attributes it to a certain [[Sthiramati]] or Sāramati. Peter Harvey finds the [[Tibetan]] attribution less plausible. | + | The [[Tibetan tradition]] [[attributes]] authorship of the [[Ratnagotravibhaga]] to him, while the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[traditions]] [[attributes]] it to a certain [[Sthiramati]] or [[Sāramati]]. [[Peter Harvey]] finds the [[Tibetan]] attribution less plausible. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

[[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | ||

[[Category:Asanga]] | [[Category:Asanga]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:09, 30 January 2024

Asaṅga (Sanskrit: असङ्ग; Tibetan: ཐོགས་མེད།; Wylie: Thogs med; traditional Chinese: 無著; pinyin: Wúzhuó; Romaji: Mujaku) was a major exponent of the Yogācāra tradition in India, also called Vijñānavāda. Traditionally, he and his half-brother Vasubandhu are regarded as the founders of this school. The two half-brothers were also major exponents of Abhidharma teachings, which were highly technical and sophisticated hermeneutics as well.

Early life

Asaṅga was born as the son of a Kṣatriya father and Brahmin mother in Puruṣapura (present day Peshawar in Pakistan), which at that time was part of the ancient kingdom of Gandhāra. Current scholarship places him in the fourth century CE. He was perhaps originally a member of the Mahīśāsaka school or the Mūlasarvāstivāda school but later converted to Mahāyāna. According to some scholars, Asaṅga's frameworks for abhidharma writings retained many underlying Mahīśāsaka traits. André Bareau writes:

[It is] sufficiently obvious that Asaṅga had been a Mahīśāsaka when he was a young monk, and that he incorporated a large part of the doctrinal opinions proper to this school within his own work after he became a great master of the Mahāyāna, when he made up what can be considered as a new and Mahāyānist Abhidharma-piṭaka.

In the record of his journeys through the kingdoms of India, Xuanzang wrote that Asaṅga was initially a Mahīśāsaka monk, but soon turned toward the Mahāyāna teachings. Asaṅga had a half-brother, Vasubandhu, who was a monk from the Sarvāstivāda school. Vasubandhu is said to have taken up Mahāyāna Buddhism after meeting with Asaṅga and one of Asaṅga's disciples.

Meditation and teachings

Asaṅga spent many years in serious meditation, during which time tradition says that he often visited Tuṣita Heaven to receive teachings from Maitreya Bodhisattva. Heavens such as Tuṣita Heaven is said to be accessible through meditation, and accounts of this are given in the writings of the Indian Buddhist monk Paramārtha, who lived during the 6th century CE. Xuanzang tells a similar account of these events:

In the great mango grove five or six li to the southwest of the city (Ayodhya), there is an old monastery where Asaṅga Bodhisattva received instructions and guided the common people. At night he went up to the place of Maitreya Bodhisattva in Tuṣita Heaven to learn the Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra, the Mahāyāna-sūtra-alaṃkāra-śāstra, the Madhyānta-vibhāga-śāstra, etc.; in the daytime, he lectured on the marvelous principles to a great audience.

Asaṅga went on to write many of the key Yogācāra treatises such as the Yogācārabhūmi-śāstra, the Mahāyāna-samgraha and the Abhidharma-samuccaya as well as other works, although there are discrepancies between the Chinese and Tibetan traditions concerning which works are attributed to him and which to Maitreya.

Abhidharma Samuccaya

Main article: Abhidharma-samuccaya

According to Walpola Rahula, the thought of the Abhidharma-samuccaya is invariably closer to that of the Pali Nikayas than is that of the Theravadin Abhidhamma.

Questions of authorship

The Tibetan tradition attributes authorship of the Ratnagotravibhaga to him, while the Chinese traditions attributes it to a certain Sthiramati or Sāramati. Peter Harvey finds the Tibetan attribution less plausible.