Difference between revisions of "Mahāsāṃghika"

| (12 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

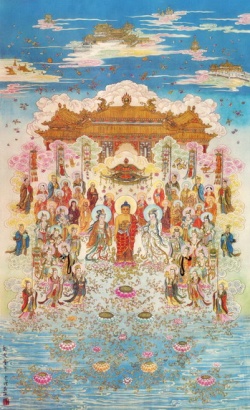

[[File:Buddha Jap.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddha Jap.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | '''[[Mahāsāṃghika]]''' one of the earliest of the | + | '''[[Mahāsāṃghika]]''' one of the earliest of the non-[[Mahāyāna]] [[Buddhist]] "sects" (the so-called [[Eighteen Schools of Hīnayāna]] [[Buddhism]]), the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] has been generally considered the precursor of [[Mahāyāna]]. However, although the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] and its subschools espoused many of the most radical [[views]] later attributed to the "[[Great Vehicle]]," other factors and [[early schools]] also contributed to the [[development]] of this {{Wiki|movement}}. |

| + | |||

| + | The {{Wiki|adherents}} of the self-styled ‘[[Majority Community]]’ or ‘[[Universal Assembly]]’, a school of [[Buddhism]] which originated in the [[schism]] with the [[Sthaviras]] that occured after the [[Second Council]] (see [[Council of Vaiśālī]]) and possibly just prior to the [[Third Council]] (see [[Council of Pāṭaliputra]] I). The | ||

| + | |||

| + | dispute that led to this [[schism]] seems to have largely concerned with [[interpretation]] of the [[Vinaya]], in [[respect]] of which one side took a more liberal approach. A [[degree]] of [[doctrinal]] [[difference]] also seems to have been involved concerning disagreements over the [[nature]] of an [[Arhat]] (see [[Mahādeva]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | This school went on to become one of the most sucessful and influential [[forms]] of [[Buddhism]] in {{Wiki|India}}, giving rise to several subschools in later years such as the [[Ekavyāvahārika]], the [[Lokottara-vāda]], and the [[Bahuśrutīya]]. Some of the teachings of this school concerning the [[nature]] of [[Buddhas]] and [[Bodhisattvas]] have features in common with [[Mahāyāna]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], but since there is no {{Wiki|evidence}} of innovation by the [[Mahāsaṃghikas]] in this [[respect]] | ||

| − | + | before the rise of the [[Mahāyāna]], in the [[view]] of some [[scholars]], such [[elements]] should be ascribed to [[Mahāyāna]] [[influence]]. According to this [[view]] there is thus not much likelihood that the [[Mahāsaṃghika]] school played a part in the formation of the [[Mahāyāna]] before the [[latter]] emerged as a {{Wiki|distinct}} [[entity]]. Other {{Wiki|scholars}} see {{Wiki|evidence}} for the converse in the formation of certain [[Mahāyāna sūtras]], such as the [[Nirvāṇa Sūtra]]. | |

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | ||

[[File:79785 o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:79785 o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] ([[Sanskrit]]: महासांघिक [[mahāsāṃghika]]; [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Chinese}}: 大眾部; pinyin: Dàzhòng Bù), literally the " | + | The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] ([[Sanskrit]]: [[महासांघिक]] [[mahāsāṃghika]]; [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Chinese}}: [[大眾部]]; pinyin: [[Dàzhòng Bù]]), literally the "[[Great Saṃgha]]," was one of the [[early Buddhist schools]] in {{Wiki|ancient India}}. |

| − | One [[reason]] for the interest in the origins of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school is that their [[Vinaya]] recension appears in several ways to represent an older redaction overall. Many [[scholars]] also look to the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] branch for the initial development of [[Mahāyāna Buddhism]]. | + | One [[reason]] for the [[interest]] in the origins of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school is that their [[Vinaya]] recension appears in several ways to represent an older redaction overall. Many [[scholars]] also look to the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] branch for the initial [[development]] of [[Mahāyāna Buddhism]]. |

Location | Location | ||

| − | The original center of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] sect was in [[Magadha]], but they also maintained important centers such as in Mathura and Karli. The [[Gokulikas]] were situated in eastern [[India]] around [[Vārāṇasī]] and [[Pāṭaliputra]]. The Ekavyahāraka and [[Lokottaravāda]] subschools were found near Peshawar around 200 BCE, and the [[Bahuśrutīya]] in [[Kośala]]. The [[Caitika]] branch was based in the Āndhra region and especially at [[Amarāvati]] and Nāgārjunakoṇḍā. This [[Caitika]] branch included the [[Pūrvaśailas]], [[Aparaśailas]], [[Rājagirikas]], and the [[Siddhārthikas]]. Finally, Madhyadesa was home to the [[Prajñaptivādins]]. | + | The original center of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[sect]] was in [[Magadha]], but they also maintained important centers such as in [[Mathura]] and [[Karli]]. The [[Gokulikas]] were situated in eastern [[India]] around [[Vārāṇasī]] and [[Pāṭaliputra]]. The [[Ekavyahāraka]] and [[Lokottaravāda]] subschools were found near {{Wiki|Peshawar}} around 200 |

| + | |||

| + | BCE, and the [[Bahuśrutīya]] in [[Kośala]]. The [[Caitika]] branch was based in the {{Wiki|Āndhra}} region and especially at [[Amarāvati]] and [[Nāgārjunakoṇḍā]]. This [[Caitika]] branch included the [[Pūrvaśailas]], [[Aparaśailas]], [[Rājagirikas]], and the [[Siddhārthikas]]. Finally, [[Madhyadesa]] was home to the [[Prajñaptivādins]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The {{Wiki|cave}} [[temples]] at the Ajaṇṭā [[Caves]], the [[Ellora Caves]], and the [[Karla Caves]] are associated with the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| − | |||

Origins | Origins | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

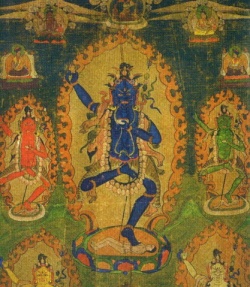

[[File:Begtse Chen.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Begtse Chen.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Most sources place the origin of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] to the [[Second Buddhist council]]. [[Traditions]] regarding the [[Second Council]] are confusing and {{Wiki|ambiguous}}, but it is agreed that the overall | + | Most sources place the origin of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] to the [[Second Buddhist council]]. [[Traditions]] regarding the [[Second Council]] are confusing and {{Wiki|ambiguous}}, but it is agreed that the overall result was the first [[schism]] in the [[Saṃgha]], between the [[Sthaviras]] and the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]], although it is |

| − | [[ | + | not agreed upon by all what the [[cause]] of this split was. [[Andrew Skilton]] has suggested that the problems of [[contradictory]] accounts are solved by the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Śāriputraparipṛcchā]], which is the earliest surviving account of the [[schism]]. In this account, the [[council]] was convened at [[Pāṭaliputra]] over matters of |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Between 148 and 170 CE, the Parthian [[monk]] [[An Shigao]] came to [[China]] and translated a work which describes the color of [[monastic robes]] (Skt. [[kāṣāya]]) utitized in five major [[Indian]] [[Buddhist]] sects, called [[Da Biqiu Sanqian Weiyi]] (Ch. [[大比丘三千威儀]]). Another text translated at a later date, the [[Śāriputraparipṛcchā]], contains a very similar passage corroborating this [[information]]. In both sources, the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] are described as wearing yellow [[robes]] The relevant portion of the [[Śāriputraparipṛcchā]] reads, "The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school diligently study the collected [[Sūtras]] and teach the true meaning, because they are the source and the center. They wear yellow [[robes]]." | + | [[vinaya]], and it is explained that the [[schism]] resulted from the majority ([[Mahāsaṃgha]]) refusing to accept the addition of {{Wiki|rules}} to the [[Vinaya]] by the minority ([[Sthaviras]]). The [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] therefore saw the [[Sthaviras]] as [[being]] a breakaway group which was attempting to modify the original [[Vinaya]]. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Scholars]] have generally agreed that the {{Wiki|matter}} of dispute was indeed a {{Wiki|matter}} of [[vinaya]], and have noted that the account of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] is bolstered by the [[vinaya]] texts themselves, as [[vinayas]] associated with the [[Sthaviras]] do contain more {{Wiki|rules}} than those of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]]. {{Wiki|Modern}} {{Wiki|scholarship}} therefore generally agrees that the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] is the oldest. According to [[Skilton]], {{Wiki|future}} [[scholars]] may | ||

| + | |||

| + | determine that a study of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school will contribute to a better [[understanding]] of the early [[Dharma-Vinaya]] than the [[Theravāda]] school. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Appearance]] and [[Language]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Appearance]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Between 148 and 170 CE, the [[Wikipedia:Parthian Empire|Parthian]] [[monk]] [[An Shigao]] came to [[China]] and translated a work which describes the {{Wiki|color}} of [[monastic robes]] (Skt. [[kāṣāya]]) utitized in five major [[Indian]] [[Buddhist]] sects, called [[Da Biqiu Sanqian Weiyi]] (Ch. [[大比丘三千威儀]]). Another text translated at a later date, the [[Śāriputraparipṛcchā]], contains a very similar passage corroborating this [[information]]. In both sources, the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] are described as | ||

| + | |||

| + | wearing [[yellow]] [[robes]] The relevant portion of the [[Śāriputraparipṛcchā]] reads, "The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school diligently study the collected [[Sūtras]] and teach the true meaning, because they are the source and the center. They wear [[yellow]] [[robes]]." | ||

[[File:Amt10.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Amt10.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | According to [[Dudjom Rinpoche]] from the [[tradition]] of [[Tibetan Buddhism]], the [[robes]] of fully [[ordained]] [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[monastics]] were to be sewn out of more than seven sections, but no more than twenty-three sections. The [[symbols]] sewn on the [[robes]] were the [[endless knot]] (Skt. [[śrīvatsa]]) and the [[conch shell]] (Skt. [[śaṅkha]]), two of the [[Eight Auspicious Signs]] in [[Buddhism]]. | + | |

| + | According to [[Dudjom Rinpoche]] from the [[tradition]] of [[Tibetan Buddhism]], the [[robes]] of fully [[ordained]] [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[monastics]] were to be sewn out of more than seven [[sections]], but no more than twenty-three [[sections]]. The [[symbols]] sewn on the [[robes]] were the [[endless knot]] (Skt. [[śrīvatsa]]) and the [[conch shell]] (Skt. [[śaṅkha]]), two of the [[Eight Auspicious Signs]] in [[Buddhism]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Language]] | [[Language]] | ||

| − | The [[Tibetan]] historian [[Buton Rinchen Drub]] wrote that the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] used Prākrit, the [[Sarvāstivādins]] used [[Sanskrit]], the [[Sthaviravāda]] used [[Paiśācī]], and the Saṃmatīya used Apabhraṃśa. | + | The [[Tibetan]] historian [[Buton Rinchen Drub]] wrote that the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] used [[Prākrit]], the [[Sarvāstivādins]] used [[Sanskrit]], the [[Sthaviravāda]] used [[Paiśācī]], and the [[Saṃmatīya]] used [[Apabhraṃśa]]. |

[[Doctrines]] and teachings. | [[Doctrines]] and teachings. | ||

| + | |||

[[Mundane]] and [[supramundane]] | [[Mundane]] and [[supramundane]] | ||

| − | The [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] held that the teachings of the [[Buddha]] were to be understood as having two principle levels of [[truth]]: a [[relative]] or conventional (Skt. [[saṃvṛti]]) [[truth]], and the [[absolute]] or [[ultimate]] (Skt. [[paramārtha]]) [[truth]]. For the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] branch of [[Buddhism]], the final and [[ultimate]] meaning of the [[Buddha's teachings]] was "beyond words," and words were merely the conventional exposition of [[ | + | The [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] held that the teachings of the [[Buddha]] were to be understood as having two [[principle]] levels of [[truth]]: a [[relative]] or [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] (Skt. [[saṃvṛti]]) [[truth]], and the [[absolute]] or [[ultimate]] (Skt. [[paramārtha]]) [[truth]]. For the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] |

| + | |||

| + | branch of [[Buddhism]], the final and [[ultimate]] meaning of the [[Buddha's teachings]] was "beyond words," and words were merely the [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[exposition]] of the [[Dharma]]. K. Venkata Ramanan writes: | ||

| + | |||

| + | The credit of having kept alive the {{Wiki|emphasis}} on the ultimacy of the [[unconditioned]] [[reality]] by drawing [[attention]] to the [[non-substantiality]] of the basic [[elements]] of [[existence]] ([[dharma-śūnyatā]]) belongs to the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]]. Every branch of these clearly drew the {{Wiki|distinction}} between the [[mundane]] and the [[ultimate]], came to {{Wiki|emphasize}} the non-ultimacy of the [[mundane]] and thus facilitated the fixing of [[attention]] on the [[ultimate]]. | ||

| − | |||

[[Buddhas]] and [[bodhisattvas]] | [[Buddhas]] and [[bodhisattvas]] | ||

[[File:Amt0.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Amt0.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] advocated the [[transcendental]] and [[supramundane]] [[nature]] of the [[buddhas]] and [[bodhisattvas]], and the fallibility of [[arhats]]. Of the 48 special theses attributed by the [[Samayabhedoparacanacakra]] to the [[Mahāsāṃghika]], [[Ekavyāvahārika]], [[Lokottaravāda]], and the [[Gokulika]], 20 [[concern]] the | |

| + | |||

| + | [[supramundane]] [[nature]] of [[buddhas]] and [[bodhisattvas]]. According to the [[Samayabhedoparacanacakra]], these four groups held that the [[Buddha]] is able to know all [[dharmas]] in a [[single moment]] of the [[mind]]. [[Yao Zhihua]] writes: | ||

| + | |||

| + | In their [[view]], the [[Buddha]] is equipped with the following [[supernatural]] qualities: {{Wiki|transcendence}} ([[lokottara]]), lack of [[defilements]], all of his utterances preaching his [[teaching]], expounding all his teachings in a single utterance, all of his sayings [[being]] true, his [[physical body]] [[being]] [[limitless]], his | ||

| − | + | [[power]] ([[prabhāva]]) [[being]] [[limitless]], the length of his [[life]] [[being]] [[limitless]], never tiring of [[enlightening]] [[sentient beings]] and [[awakening]] [[pure]] [[faith]] in them, having no [[sleep]] or [[dreams]], no pause in answering a question, and always in [[meditation]] ([[samādhi]]). | |

| − | Like the [[Mahāyāna]] [[traditions]], the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] held the [[doctrine]] of the [[existence]] of many contemporaneous [[buddhas]] throughout the [[ten directions]]. In the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] Lokānuvartana [[Sūtra]], it is stated, "The [[Buddha]] [[knows]] all the [[dharmas]] of the countless [[buddhas of the ten directions]]." It is also stated, "All [[buddhas]] have one [[body]], the [[body]] of [[ | + | A [[doctrine]] ascribed to the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] is, "The [[power]] of the [[tathāgatas]] is [[unlimited]], and the [[life]] of the [[buddhas]] is [[unlimited]]." According to [[Guang Xing]], two main aspects of the [[Buddha]] can be seen in [[Mahāsāṃghika]] teachings: the true [[Buddha]] who is [[omniscient]] and omnipotent, and the |

| + | |||

| + | [[manifested]] [[forms]] through which he {{Wiki|liberates}} [[sentient beings]] through [[skillful means]]. For the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]], the historical [[Gautama Buddha]] was one of these [[transformation]] [[bodies]] (Skt. [[nirmāṇakāya]]), while the [[essential]] real [[Buddha]] is equated with the [[Dharmakāya]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Like the [[Mahāyāna]] [[traditions]], the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] held the [[doctrine]] of the [[existence]] of many contemporaneous [[buddhas]] throughout the [[ten directions]]. In the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] Lokānuvartana [[Sūtra]], it is stated, "The [[Buddha]] [[knows]] all the [[dharmas]] of the countless [[buddhas of the ten directions]]." It is also stated, "All [[buddhas]] have one [[body]], the [[body]] of the [[Dharma]]." | ||

[[File:Begtse-shrine.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Begtse-shrine.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The {{Wiki| | + | The {{Wiki|concept}} of many [[bodhisattvas]] simultaneously working toward [[buddhahood]] is also found among the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[tradition]], and further {{Wiki|evidence}} of this is given in the [[Samayabhedoparacanacakra]], which describes the [[doctrines]] of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]]. These two [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] of contemporaneous [[bodhisattvas]] and contemporaneous [[buddhas]] were linked in some [[traditions]], and texts such as the [[Mahāprajñāpāramitā Śāstra]] use the |

| − | Pratimokṣa Vibhaṅga of the Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda (MS 2382/269) | + | [[principle]] of contemporaneous [[bodhisattvas]] to demonstrate the necessity of contemporaneous [[buddhas]] throughout the [[ten directions]]. It is [[thought]] that the [[doctrine]] of contemporaneous [[buddhas]] was already old and well established by the [[time]] of early [[Mahāyāna]] texts such as the [[Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra]], due to the clear presumptions of this [[doctrine]]. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|Manuscript}} [[collections]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhist monk]] [[Xuanzang]] visited a [[Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda]] [[monastery]] in the 7th century CE, at [[Bamiyan]], {{Wiki|Afghanistan}}, and this [[monastery]] site has since been rediscovered by {{Wiki|archaeologists}}. Birchbark and palm leaf [[manuscripts]] of texts in this [[monastery's]] collection, [[including]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Mahāyāna sūtras]], have been discovered at the site, and these are now located in the {{Wiki|Schøyen Collection}}. Some [[manuscripts]] are in the {{Wiki|Gāndhārī}} [[language]] and [[Kharoṣṭhī script]], while others are in [[Sanskrit]] and written in [[forms]] of the [[Gupta script]]. Manuscripts and fragments that have survived from this [[monastery's]] collection include the following source texts: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Pratimokṣa Vibhaṅga]] of the [[Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda]] (MS 2382/269) | ||

[[Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra]], a [[sūtra]] from the [[Āgamas]] (MS 2179/44) | [[Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra]], a [[sūtra]] from the [[Āgamas]] (MS 2179/44) | ||

| − | + | [[Caṃgī Sūtra]], a [[sūtra]] from the [[Āgamas]] (MS 2376) | |

| − | [[Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra]], a [[Mahāyāna | + | [[Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra]], a [[Mahāyāna sūtra]] (MS 2385) |

| − | [[Bhaiṣajyaguru]] [[Sūtra]], a [[Mahāyāna | + | [[Bhaiṣajyaguru]] [[Sūtra]], a [[Mahāyāna sūtra]] (MS 2385) |

| − | [[Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra]], a [[Mahāyāna | + | [[Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra]], a [[Mahāyāna sūtra]] (MS 2378) |

| − | + | [[Pravāraṇa Sūtra]], a [[Mahāyāna]] [[sūtra]] (MS 2378) | |

| − | + | [[Sarvadharmapravṛttinirdeśa Sūtra]], a [[Mahāyāna sūtra]] (MS 2378) | |

| − | + | [[Ajātaśatrukaukṛtyavinodana Sūtra]], a [[Mahāyāna sūtra]] (MS 2378) | |

[[Śāriputra Abhidharma Śāstra]] (MS 2375/08) | [[Śāriputra Abhidharma Śāstra]] (MS 2375/08) | ||

[[File:BlackDakini47oi.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:BlackDakini47oi.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Abhidharma]] | [[Abhidharma]] | ||

| − | According to some sources, [[abhidharma]] was not accepted as {{Wiki|canonical}} by the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school. The [[Theravādin]] [[Dīpavaṃsa]], for | + | According to some sources, [[abhidharma]] was not accepted as {{Wiki|canonical}} by the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school. The [[Theravādin]] [[Dīpavaṃsa]], for example, records that the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] had no [[abhidharma]]. However, other sources indicate that there were such [[collections]] of [[abhidharma]]. During the early 5th century, the |

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[pilgrim]] [[Faxian]] is said to have found a [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[abhidharma]] at a [[monastery]] in [[Pāṭaliputra]]. When [[Xuanzang]] visited [[Dhānyakaṭaka]], he wrote that the [[monks]] of this region were [[Mahāsāṃghikas]], and mentions the [[Pūrvaśailas]] specifically. Near [[Dhānyakaṭaka]], he met two | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[bhikṣus]] and studied [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[abhidharma]] with them for several months, during which [[time]] they also studied various [[Mahāyāna śāstras]] together under [[Xuanzang's]] [[direction]]. On the basis of textual {{Wiki|evidence}} as well as {{Wiki|inscriptions}} at [[Nāgārjunakoṇḍā]], Joseph Walser concludes that | ||

| + | |||

| + | at least some [[Mahāsāṃghika]] sects probably had an [[abhidharma]] collection, and that it likely contained five or six [[books]]. | ||

Relationship to [[Mahāyāna]]. | Relationship to [[Mahāyāna]]. | ||

| − | Acceptance of [[Mahāyāna]] | + | [[Acceptance]] of [[Mahāyāna]] |

| − | In the 6th century CE, [[Paramārtha]], a [[Buddhist monk]] from [[Ujjain]] in central [[India]], wrote about a special affiliation of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school with the [[Mahāyāna]] [[tradition]]. He associates the initial composition and acceptance of [[Mahāyāna sūtras]] with the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] branch of [[Buddhism]] He states that 200 years after the [[parinirvāṇa]] of the [[Buddha]], much of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school moved north of [[Rājagṛha]], and were divided over whether the [[Mahāyāna]] teachings should be incorporated formally into their [[Tripiṭaka]]. According to this account, they split into three groups based upon the [[relative]] [[manner]] and degree to which they accepted the | + | In the 6th century CE, [[Paramārtha]], a [[Buddhist monk]] from [[Ujjain]] in central [[India]], wrote about a special affiliation of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school with the [[Mahāyāna]] [[tradition]]. He associates the initial composition and [[acceptance]] of [[Mahāyāna sūtras]] with the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] branch of [[Buddhism]] He states that 200 years after the [[parinirvāṇa]] of the [[Buddha]], much of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] school moved [[north]] of [[Rājagṛha]], and were divided over whether the [[Mahāyāna]] |

| + | |||

| + | teachings should be incorporated formally into their [[Tripiṭaka]]. According to this account, they split into [[three groups]] based upon the [[relative]] [[manner]] and [[degree]] to which they accepted the authority of these [[Mahāyāna]] texts. [[Paramārtha]] states that the [[Gokulika sect]] did not accept the [[Mahāyāna sūtras]] as [[buddhavacana]] ("words of the [[Buddha]]"), while the [[Lokottaravāda]] [[sect]] and the [[Ekavyāvahārika]] [[sect]] did accept the [[Mahāyāna sūtras]] as [[buddhavacana]]. | ||

[[File:Amt7.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Amt7.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Paramārtha]] also wrote about the origins of the [[Bahuśrutīya]] sect in connection with acceptance of [[Mahāyāna]] teachings. According to his account, the founder of the [[Bahuśrutīya]] sect was named [[Yājñavalkya]]. In Paramārtha's account, [[Yājñavalkya]] is said to have lived during the [[time]] of the [[Buddha]], and to have [[heard]] his discourses, but was in a profound state of [[samādhi]] during the [[time]] of the [[Buddha's]] [[parinirvāṇa]]. After [[Yājñavalkya]] emerged from this [[samādhi]] 200 years later, he discovered that the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] were [[teaching]] only the [[superficial]] meaning of the [[sūtras]], and therefore founded the [[Bahuśrutīya]] sect in [[order]] to expound the full meaning. According to [[Paramārtha]], the [[Bahuśrutīya school]] was formed in [[order]] to fully embrace both "[[conventional truth]]" and "[[ultimate truth]]." According to [[Sree Padma]] and Anthony Barber, the [[Bahuśrutīya]] understanding of this full exposition included the [[Mahāyāna]] teachings. | + | [[Paramārtha]] also wrote about the origins of the [[Bahuśrutīya]] [[sect]] in [[connection]] with [[acceptance]] of [[Mahāyāna]] teachings. According to his account, the founder of the [[Bahuśrutīya]] [[sect]] was named [[Yājñavalkya]]. In [[Paramārtha's]] account, [[Yājñavalkya]] is said to have lived during the [[time]] of the [[Buddha]], and to have [[heard]] his [[discourses]], but was in a profound [[state]] of [[samādhi]] during the [[time]] of the [[Buddha's]] [[parinirvāṇa]]. After [[Yājñavalkya]] emerged from |

| + | |||

| + | this [[samādhi]] 200 years later, he discovered that the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] were [[teaching]] only the [[superficial]] meaning of the [[sūtras]], and therefore founded the [[Bahuśrutīya]] [[sect]] in [[order]] to expound the full meaning. According to [[Paramārtha]], the [[Bahuśrutīya school]] was formed in [[order]] to fully embrace both " | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[conventional truth]]" and "[[ultimate truth]]." According to [[Sree Padma]] and Anthony Barber, the [[Bahuśrutīya]] [[understanding]] of this full [[exposition]] included the [[Mahāyāna]] teachings. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Prajñāpāramitā]] | [[Prajñāpāramitā]] | ||

| − | A number of [[scholars]] have proposed that the [[Mahāyāna]] [[Prajñāpāramitā]] teachings were first developed by the [[Caitika]] subsect of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]]. They believe that the [[Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra]] originated amongst the southern [[Mahāsāṃghika]] schools of the Āndhra region, along the Kṛṣṇa [[River]]. These [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] had two famous [[monasteries]] near the [[Amarāvati]] and the [[Dhānyakaṭaka]], which gave their names to the schools of the [[Pūrvaśailas]] and the [[Aparaśailas]]. Each of these schools had a copy of the [[Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra]] in Prakrit. [[Guang Xing]] also assesses the [[view]] of the [[Buddha]] given in the [[Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra]] as [[being]] that of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]]. {{Wiki|Edward Conze}} estimates that this [[sūtra]] originated around 100 BCE. | + | A number of [[scholars]] have proposed that the [[Mahāyāna]] [[Prajñāpāramitā]] teachings were first developed by the [[Caitika]] subsect of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]]. They believe that the [[Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra]] originated amongst the southern [[Mahāsāṃghika]] schools of the {{Wiki|Āndhra}} region, along the [[Kṛṣṇa]] [[River]]. These [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] had two famous [[monasteries]] near the [[Amarāvati]] and the [[Dhānyakaṭaka]], which gave their names to the schools of the [[Pūrvaśailas]] and the |

| + | |||

| + | [[Aparaśailas]]. Each of these schools had a copy of the [[Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra]] in {{Wiki|Prakrit}}. [[Guang Xing]] also assesses the [[view]] of the [[Buddha]] given in the [[Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra]] as [[being]] that of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]]. {{Wiki|Edward Conze}} estimates that this [[sūtra]] originated around 100 BCE. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Tathāgatagarbha]] | [[Tathāgatagarbha]] | ||

| − | Brian Edward Brown, a specialist in [[Tathāgatagarbha]] [[doctrines]], writes that it has been determined that the composition of the [[Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra]] occurred during the Īkṣvāku Dynasty in the 3rd century CE, as a product of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] of the Āndhra region (i.e. the [[Caitika]] schools). Wayman has outlined eleven points of complete agreement between the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] and the [[Śrīmālā]], along with four major arguments for this association. [[Sree Padma]] and Anthony Barber also associate the earlier development of the [[Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra]] with the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]], and conclude that the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] of the Āndhra region were responsible for the inception of the [[Tathāgatagarbha]] [[doctrine]]. | + | Brian Edward Brown, a specialist in [[Tathāgatagarbha]] [[doctrines]], writes that it has been determined that the composition of the [[Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra]] occurred during the [[Wikipedia:Andhra Ikshvaku|Īkṣvāku Dynasty]] in the 3rd century CE, as a product of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] of the {{Wiki|Āndhra}} region (i.e. the [[Caitika]] schools). [[Wayman]] has outlined eleven points of complete agreement between the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] and the [[Śrīmālā]], along with four major arguments for this association. [[Sree Padma]] and Anthony Barber also associate the earlier [[development]] of the [[Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra]] with the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]], and conclude that the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] of the {{Wiki|Āndhra}} region were responsible for the inception of the [[Tathāgatagarbha]] [[doctrine]]. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Bodhisattva]] canons | [[Bodhisattva]] canons | ||

[[File:Bhikkhunis.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bhikkhunis.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Within the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] branch, the [[Bahuśrutīyas]] are said to have included a [[Bodhisattva Piṭaka]] in their [[canon]], and [[Paramārtha]] wrote that the [[Bahuśrutīyas]] accepted both the [[Hīnayāna]] and [[Mahāyāna]] teachings. In the 6th century CE, [[Bhāvaviveka]] speaks of the [[Siddhārthikas]] using a [[Vidyādhāra Piṭaka]], and the [[Pūrvaśailas]] and [[Aparaśailas]] both using a [[Bodhisattva Piṭaka]], all implying [[collections]] of [[Mahāyāna]] texts within the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] schools. During the same period, [[Avalokitavrata]] speaks of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] using a "[[Great Āgama Piṭaka]]," which is then associated with [[Mahāyāna sūtras]] such as the [[Prajñāparamitā]] and the [[Daśabhūmika Sūtra]]. | + | Within the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] branch, the [[Bahuśrutīyas]] are said to have included a [[Bodhisattva Piṭaka]] in their [[canon]], and [[Paramārtha]] wrote that the [[Bahuśrutīyas]] accepted both the [[Hīnayāna]] and [[Mahāyāna]] teachings. In the 6th century CE, [[Bhāvaviveka]] speaks of the [[Siddhārthikas]] using a [[Vidyādhāra Piṭaka]], and the [[Pūrvaśailas]] and [[Aparaśailas]] both using a [[Bodhisattva Piṭaka]], all implying [[collections]] of [[Mahāyāna]] texts within the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] |

| + | |||

| + | schools. During the same period, [[Avalokitavrata]] speaks of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] using a "[[Great Āgama Piṭaka]]," which is then associated with [[Mahāyāna sūtras]] such as the [[Prajñāparamitā]] and the [[Daśabhūmika Sūtra]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[Views]] of [[scholars]] | [[Views]] of [[scholars]] | ||

| − | According to A.K. Warder, it is "clearly" the case that the [[Mahāyāna]] teachings originally came from the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] branch of [[Buddhism]]. [[André Bareau]] has stated that there can be found [[Mahāyāna]] {{Wiki|ontology}} prefigured in the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] schools, and has [[offered]] an array of evidence | + | According to {{Wiki|A.K. Warder}}, it is "clearly" the case that the [[Mahāyāna]] teachings originally came from the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] branch of [[Buddhism]]. [[André Bareau]] has stated that there can be found [[Mahāyāna]] {{Wiki|ontology}} prefigured in the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] schools, and has [[offered]] an array of {{Wiki|evidence}} to support this conclusion. Bareau traces the origin of the [[Mahāyāna]] [[tradition]] to the older [[Mahāsāṃghika]] schools in regions such as [[Odisha]], [[Kosala]], |

| + | |||

| + | [[Koñkana]], and so on. He then cites the [[Bahuśrutīyas]] and [[Prajñaptivādins]] as sub-sects of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] that may have played an important role in bridging the flow of [[Mahāyāna]] teachings between the northern and southern [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[traditions]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[André Bareau]] also mentions that according to [[Xuanzang]] and [[Yijing]] in the 7th century CE, the [[Mahāsāṃghika schools]] had [[essentially]] disappeared, and instead these travelers found what they described as "[[Mahāyāna]]." The region occupied by the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] was then an important center for [[Mahāyāna Buddhism]]. Bareau has proposed that [[Mahāyāna]] grew out of the [[Mahāsāṃghika schools]], and the members of the [[Mahāsāṃghika schools]] also accepted the teachings of the [[Mahāyāna]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Additionally, the extant [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] was originally procured by [[Faxian]] in the early 5th century CE at what he describes as a "[[Mahāyāna]]" [[monastery]] in [[Pāṭaliputra]]. | ||

| + | |||

| − | |||

[[Vinaya]] Recension. | [[Vinaya]] Recension. | ||

Early features | Early features | ||

| + | |||

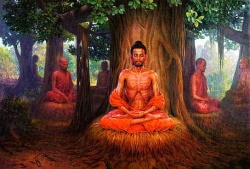

[[File:Buddha as Siddhartha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddha as Siddhartha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] recension is [[essentially]] very similar to the other recensions, as they all are to each other. The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] recension differs most from the other recensions in structure, but the rules are generally identical in meaning, if the Vibhangas (explanations) are compared. The features of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] recension which suggest that it might be an older redaction are, in brief, these: | + | The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] recension is [[essentially]] very similar to the other recensions, as they all are to each other. The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] recension differs most from the other recensions in {{Wiki|structure}}, but the {{Wiki|rules}} are generally [[identical]] in meaning, if the [[Vibhangas]] (explanations) are compared. The features of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] recension which suggest that it might be an older redaction are, in brief, these: |

| + | |||

| + | The [[Bhiksu-prakirnaka]] and [[Bhiksuni-prakirnaka]] and the [[Bhiksu-abhisamacarika-dharma]] [[sections]] of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] are generally {{Wiki|equivalent}} to the [[Khandhakas]]/ [[Skandhakas]] of the [[Sthavira]] derived schools. However, their {{Wiki|structure}} is simpler, and according to recent research by Clarke, the {{Wiki|structure}} follows a [[matika]] ({{Wiki|Matrix}}) which is also found embedded in the [[Vinayas]] of several of the [[Sthavira]] schools, suggesting that it is | ||

| + | |||

| + | presectarian. The sub-sections of the Prakirnaka [[sections]] are also titled [[pratisamyukta]] rather than [[Skandhaka]] / [[Khandhaka]]. [[Pratisamyukta]] / [[Patisamyutta]] means a section or [[chapter]] in a collection organised by [[subject]]; the '[[samyukta]]-[[principle]]', like the [[Samyutta-Nikaya]] / [[Samyukta-agama]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Scholars]] such as [[Master]] [[Yin Shun]], Choong {{Wiki|Moon}} Keat, and [[Bhikkhu Sujato]] have argued that the [[Samyutta]] / [[Samyukta]] represents the earliest collection among the [[Nikayas]] / [[Agamas]], and this may well imply that it is also the oldest organising [[principle]] too. (N.B. this does not necessarily say anything about the age of the contents). | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are also fewer stories in general in the [[Vinaya]] of the subsidiary school, the [[Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda]], and many of them give the [[appearance]] of badly connected obvious interpolations, whereas in the {{Wiki|structure}} of the [[Sthavira]] recensions the stories are integrated into the whole scheme. In the formulations of some of the [[pratimoksha]] {{Wiki|rules}} also, the phrasing (though generally [[identical]] in meaning to the other recensions) often appears to represent a clearer but less streamlined | ||

| + | |||

| + | version, which suggests it might be older. This is particularly noticeable in the [[Bhiksuni-Vinaya]], which has not been as well preserved as the [[Bhiksu-Vinaya]] in general in all the recensions. Yet the formulation of certain {{Wiki|rules}} which seem very confused in the other recensions (e.g. [[Bhikkhuni]] [[Sanghadisesa]] three = six in the Ma-L) seems to better represent what would be expected of a [[root]] formulation which could lead to the variety of confused formulations we see (presumably later) in the | ||

| + | |||

| + | other recensions. The formulation of this {{Wiki|rule}} (as an example) also reflects a semi-parallel formulation to a closely related {{Wiki|rule}} for [[Bhiksus]] which is found in a more similar [[form]] in all the [[Vinayas]] (Pc64 in [[Pali]]). | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Depiction of [[Devadatta]] | Depiction of [[Devadatta]] | ||

[[File:Centre10.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Centre10.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | According to [[Reginald Ray]], the [[Mahāsāṃghika | + | According to [[Reginald Ray]], the [[Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya]] mentions the figure of [[Devadatta]], but in a way that is different from the [[vinayas]] of the [[Sthavira]] branch. According to this study, the earliest [[vinaya]] material common to all sects simply depicts [[Devadatta]] as a [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|saint}} who wishes for the |

| + | |||

| + | [[monks]] to [[live]] a rigorous [[lifestyle]]. This has led Ray to regard the story of [[Devadatta]] as a legend produced by the [[Sthavira]] group. However, upon examining the same [[vinaya]] materials, [[Bhikkhu Sujato]] has written that the portrayals of [[Devadatta]] are largely consistent between the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] and the | ||

| + | |||

| + | other [[vinayas]], and that the supposed discrepancy is simply due to the minimalist {{Wiki|literary}} style of the [[Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya]]. He also points to other parts of the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] that clearly portray [[Devadatta]] as a villain, as well as similar portrayals that [[exist]] in the [[Lokottaravādin]] [[Mahāvastu]]. | ||

{{Wiki|Chinese}} translation | {{Wiki|Chinese}} translation | ||

| − | The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] is extant in the [[Chinese Buddhist Canon]] as Mohesengzhi Lü (摩訶僧祗律; [[Taishō Tripiṭaka]] 1425). The [[vinaya]] was originally procured by [[Faxian]] in the early 5th century CE at a [[Mahāyāna]] [[monastery]] in [[Pāṭaliputra]]. This [[vinaya]] was then translated into {{Wiki|Chinese}} as a joint [[effort]] between [[Faxian]] and [[Buddhabhadra]] in 416 CE, and the completed translation is 40 fascicles in length. According to [[Faxian]], in Northern [[India]], the [[vinaya]] teachings were typically only passed down by [[tradition]] through [[word]] of mouth and memorization. For this [[reason]], it was difficult for him to procure manuscripts of the [[vinayas]] that were used in [[India]]. The [[Mahāsāṃghika | + | The [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[Vinaya]] is extant in the [[Chinese Buddhist Canon]] as [[Mohesengzhi Lü]] ([[摩訶僧祗律]]; [[Taishō Tripiṭaka]] 1425). The [[vinaya]] was originally procured by [[Faxian]] in the early 5th century CE at a [[Mahāyāna]] [[monastery]] in [[Pāṭaliputra]]. This [[vinaya]] was then translated into {{Wiki|Chinese}} as a joint [[effort]] between [[Faxian]] and [[Buddhabhadra]] in 416 CE, and the completed translation is 40 fascicles in length. According to [[Faxian]], in [[Northern]] [[India]], the |

| + | |||

| + | [[vinaya]] teachings were typically only passed down by [[tradition]] through [[word]] of {{Wiki|mouth}} and [[memorization]]. For this [[reason]], it was difficult for him to procure [[manuscripts]] of the [[vinayas]] that were used in [[India]]. The [[Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya]] was reputed to be the original [[vinaya]] from the [[lifetime]] of the [[Buddha]], and "the most correct and complete." | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Legacy | Legacy | ||

| − | Although [[Faxian]] procured the [[Mahāsāṃghika | + | Although [[Faxian]] procured the [[Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya]] in [[India]] and had this translated into {{Wiki|Chinese}}, the [[tradition]] of [[Chinese Buddhism]] eventually settled on the [[Dharmaguptaka]] [[Vinaya]] instead. At the [[time]] of [[Faxian]], the [[Sarvāstivāda]] [[Vinaya]] was the most common [[vinaya]] [[tradition]] in [[China]]. |

| + | |||

| + | In the 7th century, [[Yijing]] wrote that in eastern [[China]], most [[people]] followed the [[Dharmaguptaka]] [[Vinaya]], while the [[Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya]] was used in earlier times in Guanzhong (the region around [[Chang'an]]), and that the [[Sarvāstivāda Vinaya]] was prominent in the [[Yangzi]] [[River]] area and further [[south]]. In | ||

| + | |||

| + | the 7th century, the [[existence]] of multiple [[Vinaya]] [[lineages]] throughout [[China]] was criticized by prominent [[Vinaya]] [[masters]] such as [[Yijing]] and [[Dao'an]] (654–717). In the early 8th century, [[Dao'an]] gained the support of [[Emperor]] [[Zhongzong]] of [[Tang]], and an {{Wiki|imperial}} {{Wiki|edict}} was issued that the [[saṃgha]] in [[China]] should use only the [[Dharmaguptaka]] [[Vinaya]] for [[ordination]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Atisha]] was [[ordained]] in the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] [[lineage]]. However, because the [[Tibetan]] [[Emperor]] [[Ralpacan]] had decreed that only the [[Mūlasarvāstivāda]] [[order]] would be permitted in [[Tibet]], he did not ordain anyone. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://www.academicroom.com/humanities/religion/buddhist-studies/buddhist-sects/mahasamghika www.academicroom.com] | [http://www.academicroom.com/humanities/religion/buddhist-studies/buddhist-sects/mahasamghika www.academicroom.com] | ||

| − | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | + | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]][[Category:Mahāsāṃghika]] |

| − | |||

| − | [[Category:Mahāsāṃghika]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:29, 15 June 2024

Mahāsāṃghika one of the earliest of the non-Mahāyāna Buddhist "sects" (the so-called Eighteen Schools of Hīnayāna Buddhism), the Mahāsāṃghika has been generally considered the precursor of Mahāyāna. However, although the Mahāsāṃghika and its subschools espoused many of the most radical views later attributed to the "Great Vehicle," other factors and early schools also contributed to the development of this movement.

The adherents of the self-styled ‘Majority Community’ or ‘Universal Assembly’, a school of Buddhism which originated in the schism with the Sthaviras that occured after the Second Council (see Council of Vaiśālī) and possibly just prior to the Third Council (see Council of Pāṭaliputra I). The

dispute that led to this schism seems to have largely concerned with interpretation of the Vinaya, in respect of which one side took a more liberal approach. A degree of doctrinal difference also seems to have been involved concerning disagreements over the nature of an Arhat (see Mahādeva).

This school went on to become one of the most sucessful and influential forms of Buddhism in India, giving rise to several subschools in later years such as the Ekavyāvahārika, the Lokottara-vāda, and the Bahuśrutīya. Some of the teachings of this school concerning the nature of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas have features in common with Mahāyāna concepts, but since there is no evidence of innovation by the Mahāsaṃghikas in this respect

before the rise of the Mahāyāna, in the view of some scholars, such elements should be ascribed to Mahāyāna influence. According to this view there is thus not much likelihood that the Mahāsaṃghika school played a part in the formation of the Mahāyāna before the latter emerged as a distinct entity. Other scholars see evidence for the converse in the formation of certain Mahāyāna sūtras, such as the Nirvāṇa Sūtra.

The Mahāsāṃghika (Sanskrit: महासांघिक mahāsāṃghika; traditional Chinese: 大眾部; pinyin: Dàzhòng Bù), literally the "Great Saṃgha," was one of the early Buddhist schools in ancient India.

One reason for the interest in the origins of the Mahāsāṃghika school is that their Vinaya recension appears in several ways to represent an older redaction overall. Many scholars also look to the Mahāsāṃghika branch for the initial development of Mahāyāna Buddhism.

Location

The original center of the Mahāsāṃghika sect was in Magadha, but they also maintained important centers such as in Mathura and Karli. The Gokulikas were situated in eastern India around Vārāṇasī and Pāṭaliputra. The Ekavyahāraka and Lokottaravāda subschools were found near Peshawar around 200

BCE, and the Bahuśrutīya in Kośala. The Caitika branch was based in the Āndhra region and especially at Amarāvati and Nāgārjunakoṇḍā. This Caitika branch included the Pūrvaśailas, Aparaśailas, Rājagirikas, and the Siddhārthikas. Finally, Madhyadesa was home to the Prajñaptivādins.

The cave temples at the Ajaṇṭā Caves, the Ellora Caves, and the Karla Caves are associated with the Mahāsāṃghikas.

Origins

Most sources place the origin of the Mahāsāṃghikas to the Second Buddhist council. Traditions regarding the Second Council are confusing and ambiguous, but it is agreed that the overall result was the first schism in the Saṃgha, between the Sthaviras and the Mahāsāṃghikas, although it is

not agreed upon by all what the cause of this split was. Andrew Skilton has suggested that the problems of contradictory accounts are solved by the Mahāsāṃghika Śāriputraparipṛcchā, which is the earliest surviving account of the schism. In this account, the council was convened at Pāṭaliputra over matters of

vinaya, and it is explained that the schism resulted from the majority (Mahāsaṃgha) refusing to accept the addition of rules to the Vinaya by the minority (Sthaviras). The Mahāsāṃghikas therefore saw the Sthaviras as being a breakaway group which was attempting to modify the original Vinaya.

Scholars have generally agreed that the matter of dispute was indeed a matter of vinaya, and have noted that the account of the Mahāsāṃghikas is bolstered by the vinaya texts themselves, as vinayas associated with the Sthaviras do contain more rules than those of the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya. Modern scholarship therefore generally agrees that the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya is the oldest. According to Skilton, future scholars may

determine that a study of the Mahāsāṃghika school will contribute to a better understanding of the early Dharma-Vinaya than the Theravāda school.

Appearance and Language

Appearance

Between 148 and 170 CE, the Parthian monk An Shigao came to China and translated a work which describes the color of monastic robes (Skt. kāṣāya) utitized in five major Indian Buddhist sects, called Da Biqiu Sanqian Weiyi (Ch. 大比丘三千威儀). Another text translated at a later date, the Śāriputraparipṛcchā, contains a very similar passage corroborating this information. In both sources, the Mahāsāṃghikas are described as

wearing yellow robes The relevant portion of the Śāriputraparipṛcchā reads, "The Mahāsāṃghika school diligently study the collected Sūtras and teach the true meaning, because they are the source and the center. They wear yellow robes."

According to Dudjom Rinpoche from the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, the robes of fully ordained Mahāsāṃghika monastics were to be sewn out of more than seven sections, but no more than twenty-three sections. The symbols sewn on the robes were the endless knot (Skt. śrīvatsa) and the conch shell (Skt. śaṅkha), two of the Eight Auspicious Signs in Buddhism.

Language

The Tibetan historian Buton Rinchen Drub wrote that the Mahāsāṃghikas used Prākrit, the Sarvāstivādins used Sanskrit, the Sthaviravāda used Paiśācī, and the Saṃmatīya used Apabhraṃśa.

Doctrines and teachings.

Mundane and supramundane

The Mahāsāṃghikas held that the teachings of the Buddha were to be understood as having two principle levels of truth: a relative or conventional (Skt. saṃvṛti) truth, and the absolute or ultimate (Skt. paramārtha) truth. For the Mahāsāṃghika

branch of Buddhism, the final and ultimate meaning of the Buddha's teachings was "beyond words," and words were merely the conventional exposition of the Dharma. K. Venkata Ramanan writes:

The credit of having kept alive the emphasis on the ultimacy of the unconditioned reality by drawing attention to the non-substantiality of the basic elements of existence (dharma-śūnyatā) belongs to the Mahāsāṃghikas. Every branch of these clearly drew the distinction between the mundane and the ultimate, came to emphasize the non-ultimacy of the mundane and thus facilitated the fixing of attention on the ultimate.

Buddhas and bodhisattvas

The Mahāsāṃghikas advocated the transcendental and supramundane nature of the buddhas and bodhisattvas, and the fallibility of arhats. Of the 48 special theses attributed by the Samayabhedoparacanacakra to the Mahāsāṃghika, Ekavyāvahārika, Lokottaravāda, and the Gokulika, 20 concern the

supramundane nature of buddhas and bodhisattvas. According to the Samayabhedoparacanacakra, these four groups held that the Buddha is able to know all dharmas in a single moment of the mind. Yao Zhihua writes:

In their view, the Buddha is equipped with the following supernatural qualities: transcendence (lokottara), lack of defilements, all of his utterances preaching his teaching, expounding all his teachings in a single utterance, all of his sayings being true, his physical body being limitless, his

power (prabhāva) being limitless, the length of his life being limitless, never tiring of enlightening sentient beings and awakening pure faith in them, having no sleep or dreams, no pause in answering a question, and always in meditation (samādhi).

A doctrine ascribed to the Mahāsāṃghikas is, "The power of the tathāgatas is unlimited, and the life of the buddhas is unlimited." According to Guang Xing, two main aspects of the Buddha can be seen in Mahāsāṃghika teachings: the true Buddha who is omniscient and omnipotent, and the

manifested forms through which he liberates sentient beings through skillful means. For the Mahāsāṃghikas, the historical Gautama Buddha was one of these transformation bodies (Skt. nirmāṇakāya), while the essential real Buddha is equated with the Dharmakāya.

Like the Mahāyāna traditions, the Mahāsāṃghikas held the doctrine of the existence of many contemporaneous buddhas throughout the ten directions. In the Mahāsāṃghika Lokānuvartana Sūtra, it is stated, "The Buddha knows all the dharmas of the countless buddhas of the ten directions." It is also stated, "All buddhas have one body, the body of the Dharma."

The concept of many bodhisattvas simultaneously working toward buddhahood is also found among the Mahāsāṃghika tradition, and further evidence of this is given in the Samayabhedoparacanacakra, which describes the doctrines of the Mahāsāṃghikas. These two concepts of contemporaneous bodhisattvas and contemporaneous buddhas were linked in some traditions, and texts such as the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Śāstra use the

principle of contemporaneous bodhisattvas to demonstrate the necessity of contemporaneous buddhas throughout the ten directions. It is thought that the doctrine of contemporaneous buddhas was already old and well established by the time of early Mahāyāna texts such as the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, due to the clear presumptions of this doctrine.

Manuscript collections

The Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang visited a Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda monastery in the 7th century CE, at Bamiyan, Afghanistan, and this monastery site has since been rediscovered by archaeologists. Birchbark and palm leaf manuscripts of texts in this monastery's collection, including

Mahāyāna sūtras, have been discovered at the site, and these are now located in the Schøyen Collection. Some manuscripts are in the Gāndhārī language and Kharoṣṭhī script, while others are in Sanskrit and written in forms of the Gupta script. Manuscripts and fragments that have survived from this monastery's collection include the following source texts:

Pratimokṣa Vibhaṅga of the Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda (MS 2382/269)

Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, a sūtra from the Āgamas (MS 2179/44)

Caṃgī Sūtra, a sūtra from the Āgamas (MS 2376)

Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2385)

Bhaiṣajyaguru Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2385)

Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2378)

Pravāraṇa Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2378)

Sarvadharmapravṛttinirdeśa Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2378)

Ajātaśatrukaukṛtyavinodana Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2378)

Śāriputra Abhidharma Śāstra (MS 2375/08)

Abhidharma

According to some sources, abhidharma was not accepted as canonical by the Mahāsāṃghika school. The Theravādin Dīpavaṃsa, for example, records that the Mahāsāṃghikas had no abhidharma. However, other sources indicate that there were such collections of abhidharma. During the early 5th century, the

Chinese pilgrim Faxian is said to have found a Mahāsāṃghika abhidharma at a monastery in Pāṭaliputra. When Xuanzang visited Dhānyakaṭaka, he wrote that the monks of this region were Mahāsāṃghikas, and mentions the Pūrvaśailas specifically. Near Dhānyakaṭaka, he met two

Mahāsāṃghika bhikṣus and studied Mahāsāṃghika abhidharma with them for several months, during which time they also studied various Mahāyāna śāstras together under Xuanzang's direction. On the basis of textual evidence as well as inscriptions at Nāgārjunakoṇḍā, Joseph Walser concludes that

at least some Mahāsāṃghika sects probably had an abhidharma collection, and that it likely contained five or six books.

Relationship to Mahāyāna.

Acceptance of Mahāyāna

In the 6th century CE, Paramārtha, a Buddhist monk from Ujjain in central India, wrote about a special affiliation of the Mahāsāṃghika school with the Mahāyāna tradition. He associates the initial composition and acceptance of Mahāyāna sūtras with the Mahāsāṃghika branch of Buddhism He states that 200 years after the parinirvāṇa of the Buddha, much of the Mahāsāṃghika school moved north of Rājagṛha, and were divided over whether the Mahāyāna

teachings should be incorporated formally into their Tripiṭaka. According to this account, they split into three groups based upon the relative manner and degree to which they accepted the authority of these Mahāyāna texts. Paramārtha states that the Gokulika sect did not accept the Mahāyāna sūtras as buddhavacana ("words of the Buddha"), while the Lokottaravāda sect and the Ekavyāvahārika sect did accept the Mahāyāna sūtras as buddhavacana.

Paramārtha also wrote about the origins of the Bahuśrutīya sect in connection with acceptance of Mahāyāna teachings. According to his account, the founder of the Bahuśrutīya sect was named Yājñavalkya. In Paramārtha's account, Yājñavalkya is said to have lived during the time of the Buddha, and to have heard his discourses, but was in a profound state of samādhi during the time of the Buddha's parinirvāṇa. After Yājñavalkya emerged from

this samādhi 200 years later, he discovered that the Mahāsāṃghikas were teaching only the superficial meaning of the sūtras, and therefore founded the Bahuśrutīya sect in order to expound the full meaning. According to Paramārtha, the Bahuśrutīya school was formed in order to fully embrace both "

conventional truth" and "ultimate truth." According to Sree Padma and Anthony Barber, the Bahuśrutīya understanding of this full exposition included the Mahāyāna teachings.

Prajñāpāramitā

A number of scholars have proposed that the Mahāyāna Prajñāpāramitā teachings were first developed by the Caitika subsect of the Mahāsāṃghikas. They believe that the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra originated amongst the southern Mahāsāṃghika schools of the Āndhra region, along the Kṛṣṇa River. These Mahāsāṃghikas had two famous monasteries near the Amarāvati and the Dhānyakaṭaka, which gave their names to the schools of the Pūrvaśailas and the

Aparaśailas. Each of these schools had a copy of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra in Prakrit. Guang Xing also assesses the view of the Buddha given in the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra as being that of the Mahāsāṃghikas. Edward Conze estimates that this sūtra originated around 100 BCE.

Tathāgatagarbha

Brian Edward Brown, a specialist in Tathāgatagarbha doctrines, writes that it has been determined that the composition of the Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra occurred during the Īkṣvāku Dynasty in the 3rd century CE, as a product of the Mahāsāṃghikas of the Āndhra region (i.e. the Caitika schools). Wayman has outlined eleven points of complete agreement between the Mahāsāṃghikas and the Śrīmālā, along with four major arguments for this association. Sree Padma and Anthony Barber also associate the earlier development of the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra with the Mahāsāṃghikas, and conclude that the Mahāsāṃghikas of the Āndhra region were responsible for the inception of the Tathāgatagarbha doctrine.

Bodhisattva canons

Within the Mahāsāṃghika branch, the Bahuśrutīyas are said to have included a Bodhisattva Piṭaka in their canon, and Paramārtha wrote that the Bahuśrutīyas accepted both the Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna teachings. In the 6th century CE, Bhāvaviveka speaks of the Siddhārthikas using a Vidyādhāra Piṭaka, and the Pūrvaśailas and Aparaśailas both using a Bodhisattva Piṭaka, all implying collections of Mahāyāna texts within the Mahāsāṃghika

schools. During the same period, Avalokitavrata speaks of the Mahāsāṃghikas using a "Great Āgama Piṭaka," which is then associated with Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Prajñāparamitā and the Daśabhūmika Sūtra.

Views of scholars

According to A.K. Warder, it is "clearly" the case that the Mahāyāna teachings originally came from the Mahāsāṃghika branch of Buddhism. André Bareau has stated that there can be found Mahāyāna ontology prefigured in the Mahāsāṃghika schools, and has offered an array of evidence to support this conclusion. Bareau traces the origin of the Mahāyāna tradition to the older Mahāsāṃghika schools in regions such as Odisha, Kosala,

Koñkana, and so on. He then cites the Bahuśrutīyas and Prajñaptivādins as sub-sects of the Mahāsāṃghika that may have played an important role in bridging the flow of Mahāyāna teachings between the northern and southern Mahāsāṃghika traditions.

André Bareau also mentions that according to Xuanzang and Yijing in the 7th century CE, the Mahāsāṃghika schools had essentially disappeared, and instead these travelers found what they described as "Mahāyāna." The region occupied by the Mahāsāṃghika was then an important center for Mahāyāna Buddhism. Bareau has proposed that Mahāyāna grew out of the Mahāsāṃghika schools, and the members of the Mahāsāṃghika schools also accepted the teachings of the Mahāyāna.

Additionally, the extant Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya was originally procured by Faxian in the early 5th century CE at what he describes as a "Mahāyāna" monastery in Pāṭaliputra.

Vinaya Recension.

Early features

The Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya recension is essentially very similar to the other recensions, as they all are to each other. The Mahāsāṃghika recension differs most from the other recensions in structure, but the rules are generally identical in meaning, if the Vibhangas (explanations) are compared. The features of the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya recension which suggest that it might be an older redaction are, in brief, these:

The Bhiksu-prakirnaka and Bhiksuni-prakirnaka and the Bhiksu-abhisamacarika-dharma sections of the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya are generally equivalent to the Khandhakas/ Skandhakas of the Sthavira derived schools. However, their structure is simpler, and according to recent research by Clarke, the structure follows a matika (Matrix) which is also found embedded in the Vinayas of several of the Sthavira schools, suggesting that it is

presectarian. The sub-sections of the Prakirnaka sections are also titled pratisamyukta rather than Skandhaka / Khandhaka. Pratisamyukta / Patisamyutta means a section or chapter in a collection organised by subject; the 'samyukta-principle', like the Samyutta-Nikaya / Samyukta-agama.

Scholars such as Master Yin Shun, Choong Moon Keat, and Bhikkhu Sujato have argued that the Samyutta / Samyukta represents the earliest collection among the Nikayas / Agamas, and this may well imply that it is also the oldest organising principle too. (N.B. this does not necessarily say anything about the age of the contents).

There are also fewer stories in general in the Vinaya of the subsidiary school, the Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda, and many of them give the appearance of badly connected obvious interpolations, whereas in the structure of the Sthavira recensions the stories are integrated into the whole scheme. In the formulations of some of the pratimoksha rules also, the phrasing (though generally identical in meaning to the other recensions) often appears to represent a clearer but less streamlined

version, which suggests it might be older. This is particularly noticeable in the Bhiksuni-Vinaya, which has not been as well preserved as the Bhiksu-Vinaya in general in all the recensions. Yet the formulation of certain rules which seem very confused in the other recensions (e.g. Bhikkhuni Sanghadisesa three = six in the Ma-L) seems to better represent what would be expected of a root formulation which could lead to the variety of confused formulations we see (presumably later) in the

other recensions. The formulation of this rule (as an example) also reflects a semi-parallel formulation to a closely related rule for Bhiksus which is found in a more similar form in all the Vinayas (Pc64 in Pali).

Depiction of Devadatta

According to Reginald Ray, the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya mentions the figure of Devadatta, but in a way that is different from the vinayas of the Sthavira branch. According to this study, the earliest vinaya material common to all sects simply depicts Devadatta as a Buddhist saint who wishes for the

monks to live a rigorous lifestyle. This has led Ray to regard the story of Devadatta as a legend produced by the Sthavira group. However, upon examining the same vinaya materials, Bhikkhu Sujato has written that the portrayals of Devadatta are largely consistent between the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya and the

other vinayas, and that the supposed discrepancy is simply due to the minimalist literary style of the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya. He also points to other parts of the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya that clearly portray Devadatta as a villain, as well as similar portrayals that exist in the Lokottaravādin Mahāvastu.

Chinese translation

The Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya is extant in the Chinese Buddhist Canon as Mohesengzhi Lü (摩訶僧祗律; Taishō Tripiṭaka 1425). The vinaya was originally procured by Faxian in the early 5th century CE at a Mahāyāna monastery in Pāṭaliputra. This vinaya was then translated into Chinese as a joint effort between Faxian and Buddhabhadra in 416 CE, and the completed translation is 40 fascicles in length. According to Faxian, in Northern India, the

vinaya teachings were typically only passed down by tradition through word of mouth and memorization. For this reason, it was difficult for him to procure manuscripts of the vinayas that were used in India. The Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya was reputed to be the original vinaya from the lifetime of the Buddha, and "the most correct and complete."

Legacy

Although Faxian procured the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya in India and had this translated into Chinese, the tradition of Chinese Buddhism eventually settled on the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya instead. At the time of Faxian, the Sarvāstivāda Vinaya was the most common vinaya tradition in China.

In the 7th century, Yijing wrote that in eastern China, most people followed the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, while the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya was used in earlier times in Guanzhong (the region around Chang'an), and that the Sarvāstivāda Vinaya was prominent in the Yangzi River area and further south. In

the 7th century, the existence of multiple Vinaya lineages throughout China was criticized by prominent Vinaya masters such as Yijing and Dao'an (654–717). In the early 8th century, Dao'an gained the support of Emperor Zhongzong of Tang, and an imperial edict was issued that the saṃgha in China should use only the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya for ordination.

Atisha was ordained in the Mahāsāṃghika lineage. However, because the Tibetan Emperor Ralpacan had decreed that only the Mūlasarvāstivāda order would be permitted in Tibet, he did not ordain anyone.