Difference between revisions of "Taṇhā"

m (Text replacement - "Comparison" to "Comparison") |

m (Text replacement - "]]]" to "]])") |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''[[Taṇhā]]''' ([[Pāli]]; [[Sanskrit]]: [[tṛṣṇā]], also '''[[trishna]]''') literally means "[[thirst]]," and is commonly translated as [[craving]] or [[desire]]. [[Taṇhā]] is defined as the [[craving]] or [[desire]] to hold onto [[pleasurable]] [[experiences]], to be separated from [[painful]] or [[unpleasant]] [[experiences]], and for [[neutral]] [[experiences]] or [[feelings]] not to decline. In the first [[teaching]] of [[ | + | '''[[Taṇhā]]''' ([[Pāli]]; [[Sanskrit]]: [[tṛṣṇā]], also '''[[trishna]]''') literally means "[[thirst]]," and is commonly translated as [[craving]] or [[desire]]. [[Taṇhā]] is defined as the [[craving]] or [[desire]] to hold onto [[pleasurable]] [[experiences]], to be separated from [[painful]] or [[unpleasant]] [[experiences]], and for [[neutral]] [[experiences]] or [[feelings]] not to {{Wiki|decline}}. In the first [[teaching]] of The [[Buddha]] on the [[Four Noble Truths]], The [[Buddha]] identified [[taṇhā]] as a [[principal]] [[cause]] in the [[arising]] of [[Dukkha]] ([[Suffering]], [[anxiety]], [[dissatisfaction]]). [[Taṇhā]] is also identified as the eighth link in the [[Twelve Links]] of [[Dependent origination]]. |

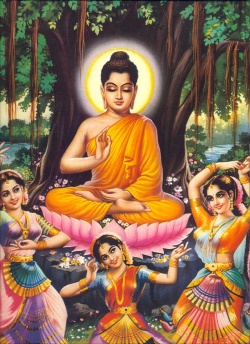

[[File:4.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:4.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

== Overview == | == Overview == | ||

| − | [[Taṇhā]] is the [[craving]] or [[desire]] to hold onto [[pleasurable]] [[experiences]], to be separated from [[painful]] or [[unpleasant]] [[experiences]], and for [[neutral]] [[experiences]] or [[feelings]] not to decline. | + | [[Taṇhā]] is the [[craving]] or [[desire]] to hold onto [[pleasurable]] [[experiences]], to be separated from [[painful]] or [[unpleasant]] [[experiences]], and for [[neutral]] [[experiences]] or [[feelings]] not to {{Wiki|decline}}. |

| − | In the first [[teaching]] of [[ | + | In the first [[teaching]] of The [[Buddha]] on the [[Four Noble Truths]], The [[Buddha]] identified [[taṇhā]] as a [[principal]] [[cause]] in the [[arising]] of [[Dukkha]] ([[Suffering]], [[anxiety]], [[dissatisfaction]]). [[Walpola Rahula]] states: |

| − | : It is this "[[thirst]]", [[desire]], [[greed]], [[craving]], [[manifesting]] itself in various ways, that gives rise to all [[forms]] of [[Suffering]] and the continuity of [[beings]]. But it should not be taken as the first [[cause]], for there is no first [[cause]] possible as, according to [[Buddhism]], everything is [[relative]] and inter-dependent. Even this "[[thirst]]", [[taṇhā]], which is considered as the [[cause]] or origin of [[Dukkha]], depends for its arising (samudaya) on something else, which is [[sensation]] ([[vedanā]]), and [[sensation]] arises depending on [[contact]] ([[Phassa]]), and so on and so forth goes on the circle which is known as [[Conditioned Genesis]] (Paṭicca-samuppāda)... So [[taṇhā]], "[[thirst]]", is not the first or the only [[cause]] of the arising of [[Dukkha]]. But it is the most palpable and immediate [[cause]], the "principal thing" and the "all-pervading thing". Hence in certain places of the original [[Pali]] texts themselves the definition of samudaya or the origin of [[Dukkha]] includes other [[defilements]] and [[impurities]] ([[kilesā]], sāsavā [[dhammā]]), in addition to [[taṇhā]] "[[thirst]]" which is always given the first place. Within the necessarily limited [[space]] of our [[discussion]], it will be sufficient if we remember that this "[[thirst]]" has as its centre the false [[idea]] of [[self]] arising out of [[ignorance]]. | + | : It is this "[[thirst]]", [[desire]], [[greed]], [[craving]], [[manifesting]] itself in various ways, that gives rise to all [[forms]] of [[Suffering]] and the continuity of [[beings]]. But it should not be taken as the first [[cause]], for there is no first [[cause]] possible as, according to [[Buddhism]], everything is [[relative]] and inter-dependent. Even this "[[thirst]]", [[taṇhā]], which is considered as the [[cause]] or origin of [[Dukkha]], depends for its [[arising]] ([[samudaya]]) on something else, which is [[sensation]] ([[vedanā]]), and [[sensation]] arises depending on [[contact]] ([[Phassa]]), and so on and so forth goes on the circle which is known as [[Conditioned Genesis]] ([[Paṭicca-samuppāda]])... So [[taṇhā]], "[[thirst]]", is not the first or the only [[cause]] of the [[arising]] of [[Dukkha]]. But it is the most palpable and immediate [[cause]], the "[[principal]] thing" and the "all-pervading thing". Hence in certain places of the original [[Pali]] texts themselves the [[definition]] of [[samudaya]] or the origin of [[Dukkha]] includes other [[defilements]] and [[impurities]] ([[kilesā]], sāsavā [[dhammā]]), in addition to [[taṇhā]] "[[thirst]]" which is always given the first place. Within the necessarily limited [[space]] of our [[discussion]], it will be sufficient if we remember that this "[[thirst]]" has as its centre the false [[idea]] of [[self]] [[arising]] out of [[ignorance]]. |

| − | [[Taṇhā]] is also identified as the eight link in the Twelve Links of [[Dependent origination]]. In the context of the twelve links, the emphasis is on the types of [[craving]] "that nourish the [[karmic]] potency that will produce the next [[lifetime]]." | + | [[Taṇhā]] is also identified as the eight link in the [[Twelve Links]] of [[Dependent origination]]. In the context of the [[twelve links]], the {{Wiki|emphasis}} is on the types of [[craving]] "that nourish the [[karmic]] [[potency]] that will produce the next [[lifetime]]." |

[[Taṇhā]] is a type of [[desire]] that can never by satisfied. [[Ajahn]] Sucitto states: | [[Taṇhā]] is a type of [[desire]] that can never by satisfied. [[Ajahn]] Sucitto states: | ||

| − | : However, taṇnhā, meaning "[[thirst]]," is not a chosen kind of [[desire]], it's a reflex. It's the [[desire]] to pull something in and feed on it, the [[desire]] that's never satisfied because it just shifts from one [[Sense base]] to another, from one [[emotional]] need to the next, from one [[sense]] of achievement to another goal. It's the [[desire]] that comes from a black hole of need, however small and manageable that need is. [[ | + | : However, taṇnhā, [[meaning]] "[[thirst]]," is not a chosen kind of [[desire]], it's a reflex. It's the [[desire]] to pull something in and feed on it, the [[desire]] that's never satisfied because it just shifts from one [[Sense base]] to another, from one [[emotional]] need to the next, from one [[sense]] of [[achievement]] to another goal. It's the [[desire]] that comes from a black hole of need, however small and manageable that need is. The [[Buddha]] said that regardless of its specific topics, this [[thirst]] relates to three channels: sense-craving (kāmataṇhā); [[craving]] to be something, to unite with an [[experience]] (bhavataṇhā); and [[craving]] to be [[nothing]], or to dissociate from an [[experience]] (vibhavataṇhā). |

== Types == | == Types == | ||

[[File:Brain-universe.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Brain-universe.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | The [[Buddha]] identified three types of [[craving]] ([[taṇhā]]): sense-craving, [[craving]] to be, [[craving]] not to be. |

===== Sense-craving ===== | ===== Sense-craving ===== | ||

* [[Pali]]: [[kāma-taṇhā]] | * [[Pali]]: [[kāma-taṇhā]] | ||

| − | * Also referred to as [[craving]] for "sensuality" or "sensual [[pleasures]]" | + | * Also referred to as [[craving]] for "[[sensuality]]" or "[[sensual]] [[pleasures]]" |

* This is a [[craving]] for [[sense]] [[objects]] which provide [[pleasant]] [[feeling]], or [[craving]] for sensory [[pleasures]]. | * This is a [[craving]] for [[sense]] [[objects]] which provide [[pleasant]] [[feeling]], or [[craving]] for sensory [[pleasures]]. | ||

| − | * [[Walpola Rahula]] states that [[Tanha]] includes not only [[desire]] for sense-pleasures, [[wealth]] and [[Power]], but also "[[desire]] for, and [[attachment]] to, ideas and ideals, [[views]], opinions, theories, conceptions and [[beliefs]] ([[Dhamma]]-[[taṇhā]])." | + | * [[Walpola Rahula]] states that [[Tanha]] includes not only [[desire]] for [[sense-pleasures]], [[wealth]] and [[Power]], but also "[[desire]] for, and [[attachment]] to, [[ideas]] and ideals, [[views]], [[opinions]], theories, conceptions and [[beliefs]] ([[Dhamma]]-[[taṇhā]])." |

===== [[Craving]] to be ===== | ===== [[Craving]] to be ===== | ||

* [[Pali]]: [[Bhava]]-[[taṇhā]] | * [[Pali]]: [[Bhava]]-[[taṇhā]] | ||

| − | * Also referred to as [[craving]] for " | + | * Also referred to as [[craving]] for "becoming" or "[[existence]]" |

* This is [[craving]] to be something, to unite with an [[experience]]. | * This is [[craving]] to be something, to unite with an [[experience]]. | ||

| − | * Ron Leifer states: "The [[desire]] for [[life]] is present in the [[body]] at [[birth]], in its homeostatic, hormonal, and reflexive mechanisms... At the more subtle level of [[ego]], the [[desire]] for [[life]] is the ego's striving to establish itself, to solidify itself, to gain a secure foothold, to prevail and dominate, and so to enjoy the [[sensuous]] delights of the [[phenomenal]] [[world]]. The [[desire]] for [[life]] [[manifests]] itself in all of ego's [[selfish]], ambitious strivings..." | + | * Ron Leifer states: "The [[desire]] for [[life]] is {{Wiki|present}} in the [[body]] at [[birth]], in its homeostatic, hormonal, and reflexive mechanisms... At the more {{Wiki|subtle}} level of [[ego]], the [[desire]] for [[life]] is the ego's striving to establish itself, to solidify itself, to gain a secure foothold, to prevail and dominate, and so to enjoy the [[sensuous]] delights of the [[phenomenal]] [[world]]. The [[desire]] for [[life]] [[manifests]] itself in all of ego's [[selfish]], ambitious strivings..." |

| − | * [[Ajahn]] Sucitto states: "[[Craving]] to be something is not a decision, it’s a reflex... So the result of [[craving]] to be solid and ongoing, to be a [[being]] that has a past and a future, together with the current wish to resolve the past and future, are combined to establish each individual’s present [[world]] as complex and unsteady. This [[thirst]] to be something keeps us reaching out for what isn’t here. And so we lose the inner [[balance]] that allows us to discern a here-and-now fulfillment in ourselves." | + | * [[Ajahn]] Sucitto states: "[[Craving]] to be something is not a [[decision]], it’s a reflex... So the result of [[craving]] to be {{Wiki|solid}} and ongoing, to be a [[being]] that has a {{Wiki|past}} and a {{Wiki|future}}, together with the current wish to resolve the {{Wiki|past}} and {{Wiki|future}}, are combined to establish each individual’s {{Wiki|present}} [[world]] as complex and unsteady. This [[thirst]] to be something keeps us reaching out for what isn’t here. And so we lose the inner [[balance]] that allows us to discern a here-and-now fulfillment in ourselves." |

===== [[Craving]] not to be ===== | ===== [[Craving]] not to be ===== | ||

* [[Pali]]: vibhava-taṇhā | * [[Pali]]: vibhava-taṇhā | ||

| − | * Also referred to as [[craving]] for "no | + | * Also referred to as [[craving]] for "no becoming" or "[[non-existence]]" or "extermination" |

* This is [[craving]] to not [[experience]] the [[world]], and to be [[nothing]]. | * This is [[craving]] to not [[experience]] the [[world]], and to be [[nothing]]. | ||

* The [[Dalai Lama]] states that [[craving]] for "[[destruction]] is a wish to be separated from [[painful]] [[feelings]]". | * The [[Dalai Lama]] states that [[craving]] for "[[destruction]] is a wish to be separated from [[painful]] [[feelings]]". | ||

| − | * Ron Leifer states: "As the [[desire]] for [[life]] is based on the [[desire]] for [[pleasure]] and [[happiness]], the [[desire]] for [[death]] is based on the [[desire]] to escape [[pain]] and | + | * Ron Leifer states: "As the [[desire]] for [[life]] is based on the [[desire]] for [[pleasure]] and [[happiness]], the [[desire]] for [[death]] is based on the [[desire]] to escape [[pain]] and ([[suffering]])... The [[desire]] for [[death]] is the yearning for relief from [[pain]], from [[anxiety]], from disappointment, {{Wiki|despair}}, and negativity." |

| − | * "The motive for the [[desire]] for [[death]] is most transparent in cases of {{Wiki|suicide}}. Clearly, [[people]] with terminal illnesses who commit {{Wiki|suicide}} are motivated by the [[desire]] to escape from [[physical]] [[pain]] and [[Suffering]]. In so-called "altruistic" {{Wiki|suicide}}, such as hari-kari, kamakazi, and other [[forms]] of socially [[conditioned]] {{Wiki|suicide}}, the motive is to avoid [[mental]] [[Suffering]]–[[shame]], humiliation, and disgrace." | + | * "The {{Wiki|motive}} for the [[desire]] for [[death]] is most transparent in cases of {{Wiki|suicide}}. Clearly, [[people]] with terminal [[illnesses]] who commit {{Wiki|suicide}} are motivated by the [[desire]] to escape from [[physical]] [[pain]] and [[Suffering]]. In so-called "{{Wiki|altruistic}}" {{Wiki|suicide}}, such as hari-kari, kamakazi, and other [[forms]] of socially [[conditioned]] {{Wiki|suicide}}, the {{Wiki|motive}} is to avoid [[mental]] [[Suffering]]–[[shame]], {{Wiki|humiliation}}, and disgrace." |

== Comparison to [[Chanda]] == | == Comparison to [[Chanda]] == | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

[[Ajahn]] Sucitto states: | [[Ajahn]] Sucitto states: | ||

| − | : Sometimes [[taṇhā]] is translated as “[[desire]],” but that gives rise to some crucial misinterpretations with reference to the way of [[Liberation]]. As we shall see, some [[form]] of [[desire]] is [[essential]] in [[order]] to aspire to, and persist in, cultivating the [[path]] out of [[Dukkha]]. [[Desire]] as an eagerness to offer, to commit, to apply oneself to [[meditation]], is called [[Chanda]]. It’s a [[psychological]] “yes,” a choice, not a pathology. In fact, you could summarize [[Dhamma]] training as the [[transformation]] of [[taṇhā]] into [[Chanda]]. It’s a process whereby we guide [[volition]], grab and hold on to the steering [[wheel]], and travel with clarity toward our deeper well-being. So we’re not trying to get rid of [[desire]] (which would take another kind of [[desire]], wouldn’t it). Instead, we are trying to transmute it, take it out of the shadow of gratification and need, and use its [[aspiration]] and [[vigor]] to bring us into [[light]] and clarity. | + | : Sometimes [[taṇhā]] is translated as “[[desire]],” but that gives rise to some crucial misinterpretations with reference to the way of [[Liberation]]. As we shall see, some [[form]] of [[desire]] is [[essential]] in [[order]] to aspire to, and persist in, [[cultivating]] the [[path]] out of [[Dukkha]]. [[Desire]] as an [[eagerness]] to offer, to commit, to apply oneself to [[meditation]], is called [[Chanda]]. It’s a [[psychological]] “yes,” a choice, not a {{Wiki|pathology}}. In fact, you could summarize [[Dhamma]] {{Wiki|training}} as the [[transformation]] of [[taṇhā]] into [[Chanda]]. It’s a process whereby we [[guide]] [[volition]], grab and hold on to the steering [[wheel]], and travel with clarity toward our deeper well-being. So we’re not trying to get rid of [[desire]] (which would take another kind of [[desire]], wouldn’t it). Instead, we are trying to transmute it, take it out of the shadow of gratification and need, and use its [[aspiration]] and [[vigor]] to bring us into [[light]] and clarity. |

== Effects == | == Effects == | ||

| − | [[Taṇhā]] is said to be a principal [[cause]] of [[Suffering]] in the [[world]]. [[Walpola Rahula]] states: | + | [[Taṇhā]] is said to be a [[principal]] [[cause]] of [[Suffering]] in the [[world]]. [[Walpola Rahula]] states: |

| − | :According to [[ | + | :According to The [[Buddha]]’s [[analysis]], all the troubles and strife in the [[world]], from little personal quarrels in families to great wars between nations and countries, arise out of this [[selfish]] ‘[[thirst]]’. From this point of [[view]], all economic, {{Wiki|political}} and {{Wiki|social}} problems are [[rooted]] in this [[selfish]] ‘[[thirst]]’. Great statesmen who try to settle international disputes and talk of [[war]] and [[peace]] only in economic and {{Wiki|political}} terms {{Wiki|touch}} the superficialities, and never go deep into the {{Wiki|real}} [[root]] of the problem. As The [[Buddha]] told Raṭṭapāla: “The [[world]] lacks and hankers, and is enslaved to “[[thirst]]” (taṇhādāso). |

In the [[Maha]]-[[Nidana]] [[Sutta]] (The [[Great Causes Discourse]]), [[Buddha]] said: | In the [[Maha]]-[[Nidana]] [[Sutta]] (The [[Great Causes Discourse]]), [[Buddha]] said: | ||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

Contemporary [[Buddhist]] [[teacher]] [[Chogyam Trungpa]] emphasizes the non-deliberate quality of [[Tanha]]. He states: | Contemporary [[Buddhist]] [[teacher]] [[Chogyam Trungpa]] emphasizes the non-deliberate quality of [[Tanha]]. He states: | ||

| − | : | + | : ([[Craving]]) is like someone who is extremely hungry. Such a [[person]] doesn't actually think in terms of eating the [[food]], chewing it and {{Wiki|swallowing}} it. Instead the [[food]] just goes into his {{Wiki|stomach}}. It's very simple, there's no [[effort]] involved, it just goes into him... [[Craving]] in this case is not so much what the weightwatcher's club talks about, but it's genuine [[craving]]. It actually just happens. We could actually say to somebody literally, "I don't know what happened, I just did it. It just happened to me. It just happens to me constantly." ... So it's instant [[craving]], rather than deliberate [[craving]] as such. At that level, there's no intellectualization at all involved. |

=== Bipolar === | === Bipolar === | ||

| − | [[Taṇhā]] encompasses both the [[desire]] to get something and its opposite, the [[desire]] to get rid of it. | + | [[Taṇhā]] encompasses both the [[desire]] to get something and its {{Wiki|opposite}}, the [[desire]] to get rid of it. |

Ron Leifer states: | Ron Leifer states: | ||

| − | : ...[[taṇhā]] itself is bipolar, divided into [[greed]] and [[hatred]], or [[passion]] and [[aggression]]. On the one hand is the [[desire]] to have something, to possess it, to [[experience]] it, to pull it in, to own it. On the other hand is the [[desire]] to avoid something, to keep it away, reject it, renounce it, destroy it, and separate it from oneself. If we call these two poles [[desire]] and [[aversion]], we can see more clearly that they represent the antithetical poles of taṇhā–the [[desire]] to possess and the [[desire]] to get rid of. | + | : ...[[taṇhā]] itself is bipolar, divided into [[greed]] and [[hatred]], or [[passion]] and [[aggression]]. On the one hand is the [[desire]] to have something, to possess it, to [[experience]] it, to pull it in, to own it. On the other hand is the [[desire]] to avoid something, to keep it away, reject it, {{Wiki|renounce}} it, destroy it, and separate it from oneself. If we call these two poles [[desire]] and [[aversion]], we can see more clearly that they represent the [[Wikipedia:Anti-life|antithetical]] poles of taṇhā–the [[desire]] to possess and the [[desire]] to get rid of. |

=== Unsatisfactory, unquenchable, addictive === | === Unsatisfactory, unquenchable, addictive === | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

Ron Leifer states: | Ron Leifer states: | ||

| − | : [[Desire]] [i.e. [[taṇhā]] | + | : [[Desire]] [i.e. [[taṇhā]]) [[causes]] [[Suffering]] by its own [[nature]] because it is inherently unsatisfactory. [[Desire]] means deprivation. To want something is to lack it, to be deprived of it. We do not want things we have, we only want things we don't have. [[Thirst]] is the [[desire]] for [[water]] and it occurs in the absence of [[water]]. Hunger is the [[feeling]] of lacking [[food]]. [[Desiring]] means not having, [[being]] frustrated, [[Suffering]]. [[Craving]] is [[Suffering]]. This is a most important [[insight]], one which we drive into secrecy by our refusal to [[acknowledge]] it, thus creating the [[esoteric]] [[knowledge]] we then seek. |

| − | Most [[people]] tend to act under the assumption that if one's [[desires]] are fulfilled it will, of itself, lead to lasting [[happiness]] or well-being. However, the [[Buddhist teachings]] state that [[desire]] for [[conditioned things]] cannot be fully satiated or satisfied, due to their [[impermanent]] nature. This is expounded in the [[Buddhist teaching]] of [[impermanence]]. | + | Most [[people]] tend to act under the assumption that if one's [[desires]] are fulfilled it will, of itself, lead to lasting [[happiness]] or well-being. However, the [[Buddhist teachings]] state that [[desire]] for [[conditioned things]] cannot be fully satiated or satisfied, due to their [[impermanent]] [[nature]]. This is expounded in the [[Buddhist teaching]] of [[impermanence]]. |

== [[Relation]] to the [[Three poisons]] == | == [[Relation]] to the [[Three poisons]] == | ||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

* [[Avidya]] ([[ignorance]]), the [[root]] of the [[Three poisons]], is also the basis for [[taṇhā]]. | * [[Avidya]] ([[ignorance]]), the [[root]] of the [[Three poisons]], is also the basis for [[taṇhā]]. | ||

| − | * [[Raga]] ([[attachment]]), the second of the [[Three poisons]], is equivalent to [[Bhava]]-[[taṇhā]] ([[craving]] to be) and [[kāma-taṇhā]] (sense-craving). | + | * [[Raga]] ([[attachment]]), the second of the [[Three poisons]], is {{Wiki|equivalent}} to [[Bhava]]-[[taṇhā]] ([[craving]] to be) and [[kāma-taṇhā]] (sense-craving). |

| − | * [[Dvesha]] ([[aversion]]), the third of the [[Three poisons]], is equivalent to vibhava-taṇhā ([[craving]] not to be). | + | * [[Dvesha]] ([[aversion]]), the third of the [[Three poisons]], is {{Wiki|equivalent}} to vibhava-taṇhā ([[craving]] not to be). |

== [[Relation]] to addiction == | == [[Relation]] to addiction == | ||

| − | [[Taṇhā]] is sometimes related to the Western [[psychological]] {{Wiki|concept}} of addiction. For example: | + | [[Taṇhā]] is sometimes related to the {{Wiki|Western}} [[psychological]] {{Wiki|concept}} of addiction. For example: |

The [[Dalai Lama]] states: | The [[Dalai Lama]] states: | ||

| − | : Much [[human]] [[Suffering]] stems from [[destructive emotions]], as [[hatred]] breeds violence or [[craving]] fuels addiction. One of our most basic responsibilities as caring [[people]] is to alleviate the [[human]] costs of such out-of-control [[emotions]]. | + | : Much [[human]] [[Suffering]] stems from [[destructive emotions]], as [[hatred]] breeds [[violence]] or [[craving]] fuels addiction. One of our most basic responsibilities as caring [[people]] is to alleviate the [[human]] costs of such out-of-control [[emotions]]. |

Ron Leifer states: | Ron Leifer states: | ||

| − | : Obsessions, compulsions, and addictions are [[desires]] out of control, [[desires]] gone wild. | + | : {{Wiki|Obsessions}}, [[compulsions]], and {{Wiki|addictions}} are [[desires]] out of control, [[desires]] gone wild. |

Mingyur [[Rinpoche]] states: | Mingyur [[Rinpoche]] states: | ||

| − | : [[Attachment]] is in many ways comparable to addiction, a compulsive dependency on {{Wiki|external}} [[objects]] or [[experiences]] to [[manufacture]] an [[illusion]] of wholeness. Unfortunately, like other addictions, [[attachment]] becomes more intense over [[time]]. | + | : [[Attachment]] is in many ways comparable to addiction, a compulsive [[dependency]] on {{Wiki|external}} [[objects]] or [[experiences]] to [[manufacture]] an [[illusion]] of [[wholeness]]. Unfortunately, like other {{Wiki|addictions}}, [[attachment]] becomes more intense over [[time]]. |

== [[Cessation]] == | == [[Cessation]] == | ||

| Line 114: | Line 114: | ||

The [[third noble truth]] teaches that the [[cessation]] of [[taṇhā]] is possible. | The [[third noble truth]] teaches that the [[cessation]] of [[taṇhā]] is possible. | ||

| − | : [[Bhikkhus]], there is a [[noble truth]] about the [[cessation]] of [[Suffering]]. It is the complete fading away and [[cessation]] of this [[craving]]; its [[abandonment]] and relinquishment; getting free from and [[being]] independent of it.” | + | : [[Bhikkhus]], there is a [[noble truth]] about the [[cessation]] of [[Suffering]]. It is the complete fading away and [[cessation]] of this [[craving]]; its [[abandonment]] and [[relinquishment]]; getting free from and [[being]] {{Wiki|independent}} of it.” |

| − | [[Cessation]] is possible by following the [[Noble Eightfold Path]]. Within this [[path]], contemplating the [[impermanent]] nature of all things is regarded as a specific antidote to [[taṇhā]]. | + | [[Cessation]] is possible by following the [[Noble Eightfold Path]]. Within this [[path]], contemplating the [[impermanent]] [[nature]] of all things is regarded as a specific antidote to [[taṇhā]]. |

== [[Mara]]'s daughter == | == [[Mara]]'s daughter == | ||

[[File:Buddha14.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddha14.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

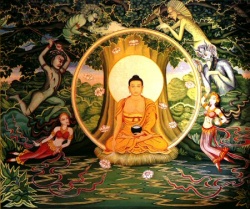

| − | [[Taṇhā]] is sometimes identified as one of Māra's three daughters, along with [[Arati]] ({{Wiki|Boredom}}), and [[Rāga]] ([[Passion]]). In some accounts of [[ | + | [[Taṇhā]] is sometimes identified as one of [[Māra's]] three daughters, along with [[Arati]] ({{Wiki|Boredom}}), and [[Rāga]] ([[Passion]]). In some accounts of The [[Buddha]]'s [[Enlightenment]], it is said that the [[demon]] [[Māra]] sent his three daughters to tempt The [[Buddha]] to give up his quest. |

| − | In a similar fashion, in Sn 436 (Saddhatissa, 1998, p. 48), [[taṇhā]] is personified as one of Death's four armies (senā) along with [[desire]] (kāmā), [[aversion]] ([[arati]]) and hunger-thirst (khuppipāsā). | + | In a similar fashion, in Sn 436 (Saddhatissa, 1998, p. 48), [[taṇhā]] is personified as one of Death's four armies (senā) along with [[desire]] ([[kāmā]]), [[aversion]] ([[arati]]) and hunger-thirst (khuppipāsā). |

== {{Wiki|Etymology}} == | == {{Wiki|Etymology}} == | ||

| − | The literal meaning of [[taṇhā]] is "[[thirst]]"; however, in [[Buddhism]] it has a technical meaning described above. In part due to the variety of possible translations, [[taṇhā]] is sometimes used as an untranslated technical term by authors [[writing]] about [[Buddhism]]. One source suggests that the opposite of [[taṇhā]] is [[Upekkha]] ([[peace]] of [[mind]], [[equanimity]]). | + | The literal [[meaning]] of [[taṇhā]] is "[[thirst]]"; however, in [[Buddhism]] it has a technical [[meaning]] described above. In part due to the variety of possible translations, [[taṇhā]] is sometimes used as an untranslated technical term by authors [[writing]] about [[Buddhism]]. One source suggests that the {{Wiki|opposite}} of [[taṇhā]] is [[Upekkha]] ([[peace]] of [[mind]], [[equanimity]]). |

| − | Smith and Novak emphasize the difficulty of translating this term; they state: | + | Smith and Novak {{Wiki|emphasize}} the difficulty of translating this term; they state: |

| − | : The [[cause]] of life’s dislocation is [[Tanha]]. Again, imprecisions of translations—all are to some degree inaccurate—make it [[wise]] to stay close to the original [[word]]. [[Tanha]] is usually translated as “[[desire]].” There is some [[truth]] in this, but if we try to make “[[desire]]” [[Tanha]]’s equivalent, we run into difficulties. To begin with, the equivalence would make this Second [[Truth]] unhelpful, for to shut down [[desires]], all [[desires]], in our present state would be to [[die]], and to [[die]] is not to solve life’s problem. But beyond [[being]] unhelpful, the claim of equivalence would be flatly wrong, for there are some [[desires]] [[ | + | : The [[cause]] of life’s dislocation is [[Tanha]]. Again, imprecisions of translations—all are to some [[degree]] inaccurate—make it [[wise]] to stay close to the original [[word]]. [[Tanha]] is usually translated as “[[desire]].” There is some [[truth]] in this, but if we try to make “[[desire]]” [[Tanha]]’s {{Wiki|equivalent}}, we run into difficulties. To begin with, the equivalence would make this Second [[Truth]] unhelpful, for to shut down [[desires]], all [[desires]], in our {{Wiki|present}} state would be to [[die]], and to [[die]] is not to solve life’s problem. But [[beyond]] [[being]] unhelpful, the claim of equivalence would be flatly wrong, for there are some [[desires]] The [[Buddha]] explicitly advocated—the [[desire]] for [[liberation]], for example, or for the [[happiness]] of others. |

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

| Line 137: | Line 137: | ||

[[Category:Kleshas]] | [[Category:Kleshas]] | ||

[[Category:Craving]] | [[Category:Craving]] | ||

| − | + | {{PaliTerminology}} | |

Latest revision as of 03:26, 5 April 2016

Taṇhā (Pāli; Sanskrit: tṛṣṇā, also trishna) literally means "thirst," and is commonly translated as craving or desire. Taṇhā is defined as the craving or desire to hold onto pleasurable experiences, to be separated from painful or unpleasant experiences, and for neutral experiences or feelings not to decline. In the first teaching of The Buddha on the Four Noble Truths, The Buddha identified taṇhā as a principal cause in the arising of Dukkha (Suffering, anxiety, dissatisfaction). Taṇhā is also identified as the eighth link in the Twelve Links of Dependent origination.

Overview

Taṇhā is the craving or desire to hold onto pleasurable experiences, to be separated from painful or unpleasant experiences, and for neutral experiences or feelings not to decline.

In the first teaching of The Buddha on the Four Noble Truths, The Buddha identified taṇhā as a principal cause in the arising of Dukkha (Suffering, anxiety, dissatisfaction). Walpola Rahula states:

- It is this "thirst", desire, greed, craving, manifesting itself in various ways, that gives rise to all forms of Suffering and the continuity of beings. But it should not be taken as the first cause, for there is no first cause possible as, according to Buddhism, everything is relative and inter-dependent. Even this "thirst", taṇhā, which is considered as the cause or origin of Dukkha, depends for its arising (samudaya) on something else, which is sensation (vedanā), and sensation arises depending on contact (Phassa), and so on and so forth goes on the circle which is known as Conditioned Genesis (Paṭicca-samuppāda)... So taṇhā, "thirst", is not the first or the only cause of the arising of Dukkha. But it is the most palpable and immediate cause, the "principal thing" and the "all-pervading thing". Hence in certain places of the original Pali texts themselves the definition of samudaya or the origin of Dukkha includes other defilements and impurities (kilesā, sāsavā dhammā), in addition to taṇhā "thirst" which is always given the first place. Within the necessarily limited space of our discussion, it will be sufficient if we remember that this "thirst" has as its centre the false idea of self arising out of ignorance.

Taṇhā is also identified as the eight link in the Twelve Links of Dependent origination. In the context of the twelve links, the emphasis is on the types of craving "that nourish the karmic potency that will produce the next lifetime."

Taṇhā is a type of desire that can never by satisfied. Ajahn Sucitto states:

- However, taṇnhā, meaning "thirst," is not a chosen kind of desire, it's a reflex. It's the desire to pull something in and feed on it, the desire that's never satisfied because it just shifts from one Sense base to another, from one emotional need to the next, from one sense of achievement to another goal. It's the desire that comes from a black hole of need, however small and manageable that need is. The Buddha said that regardless of its specific topics, this thirst relates to three channels: sense-craving (kāmataṇhā); craving to be something, to unite with an experience (bhavataṇhā); and craving to be nothing, or to dissociate from an experience (vibhavataṇhā).

Types

The Buddha identified three types of craving (taṇhā): sense-craving, craving to be, craving not to be.

Sense-craving

- Pali: kāma-taṇhā

- Also referred to as craving for "sensuality" or "sensual pleasures"

- This is a craving for sense objects which provide pleasant feeling, or craving for sensory pleasures.

- Walpola Rahula states that Tanha includes not only desire for sense-pleasures, wealth and Power, but also "desire for, and attachment to, ideas and ideals, views, opinions, theories, conceptions and beliefs (Dhamma-taṇhā)."

Craving to be

- Pali: Bhava-taṇhā

- Also referred to as craving for "becoming" or "existence"

- This is craving to be something, to unite with an experience.

- Ron Leifer states: "The desire for life is present in the body at birth, in its homeostatic, hormonal, and reflexive mechanisms... At the more subtle level of ego, the desire for life is the ego's striving to establish itself, to solidify itself, to gain a secure foothold, to prevail and dominate, and so to enjoy the sensuous delights of the phenomenal world. The desire for life manifests itself in all of ego's selfish, ambitious strivings..."

- Ajahn Sucitto states: "Craving to be something is not a decision, it’s a reflex... So the result of craving to be solid and ongoing, to be a being that has a past and a future, together with the current wish to resolve the past and future, are combined to establish each individual’s present world as complex and unsteady. This thirst to be something keeps us reaching out for what isn’t here. And so we lose the inner balance that allows us to discern a here-and-now fulfillment in ourselves."

Craving not to be

- Pali: vibhava-taṇhā

- Also referred to as craving for "no becoming" or "non-existence" or "extermination"

- This is craving to not experience the world, and to be nothing.

- The Dalai Lama states that craving for "destruction is a wish to be separated from painful feelings".

- Ron Leifer states: "As the desire for life is based on the desire for pleasure and happiness, the desire for death is based on the desire to escape pain and (suffering)... The desire for death is the yearning for relief from pain, from anxiety, from disappointment, despair, and negativity."

- "The motive for the desire for death is most transparent in cases of suicide. Clearly, people with terminal illnesses who commit suicide are motivated by the desire to escape from physical pain and Suffering. In so-called "altruistic" suicide, such as hari-kari, kamakazi, and other forms of socially conditioned suicide, the motive is to avoid mental Suffering–shame, humiliation, and disgrace."

Comparison to Chanda

The Buddhist teachings contrast the reflexive, self-centered desire of taṇhā with the wholesome type of desire for well-being, called Chanda.

Ajahn Sucitto states:

- Sometimes taṇhā is translated as “desire,” but that gives rise to some crucial misinterpretations with reference to the way of Liberation. As we shall see, some form of desire is essential in order to aspire to, and persist in, cultivating the path out of Dukkha. Desire as an eagerness to offer, to commit, to apply oneself to meditation, is called Chanda. It’s a psychological “yes,” a choice, not a pathology. In fact, you could summarize Dhamma training as the transformation of taṇhā into Chanda. It’s a process whereby we guide volition, grab and hold on to the steering wheel, and travel with clarity toward our deeper well-being. So we’re not trying to get rid of desire (which would take another kind of desire, wouldn’t it). Instead, we are trying to transmute it, take it out of the shadow of gratification and need, and use its aspiration and vigor to bring us into light and clarity.

Effects

Taṇhā is said to be a principal cause of Suffering in the world. Walpola Rahula states:

- According to The Buddha’s analysis, all the troubles and strife in the world, from little personal quarrels in families to great wars between nations and countries, arise out of this selfish ‘thirst’. From this point of view, all economic, political and social problems are rooted in this selfish ‘thirst’. Great statesmen who try to settle international disputes and talk of war and peace only in economic and political terms touch the superficialities, and never go deep into the real root of the problem. As The Buddha told Raṭṭapāla: “The world lacks and hankers, and is enslaved to “thirst” (taṇhādāso).

In the Maha-Nidana Sutta (The Great Causes Discourse), Buddha said:

- Now, craving is dependent on feeling, seeking is dependent on craving, acquisition is dependent on seeking, ascertainment is dependent on acquisition, desire and passion is dependent on ascertainment, attachment is dependent on desire and passion, possessiveness is dependent on attachment, stinginess is dependent on possessiveness, defensiveness is dependent on stinginess, and because of defensiveness, dependent on defensiveness, various evil, unskillful phenomena come into play: the taking up of sticks and knives; conflicts, quarrels, and disputes; accusations, divisive speech, and lies.

Qualities

Non-deliberate

Contemporary Buddhist teacher Chogyam Trungpa emphasizes the non-deliberate quality of Tanha. He states:

- (Craving) is like someone who is extremely hungry. Such a person doesn't actually think in terms of eating the food, chewing it and swallowing it. Instead the food just goes into his stomach. It's very simple, there's no effort involved, it just goes into him... Craving in this case is not so much what the weightwatcher's club talks about, but it's genuine craving. It actually just happens. We could actually say to somebody literally, "I don't know what happened, I just did it. It just happened to me. It just happens to me constantly." ... So it's instant craving, rather than deliberate craving as such. At that level, there's no intellectualization at all involved.

Bipolar

Taṇhā encompasses both the desire to get something and its opposite, the desire to get rid of it.

Ron Leifer states:

- ...taṇhā itself is bipolar, divided into greed and hatred, or passion and aggression. On the one hand is the desire to have something, to possess it, to experience it, to pull it in, to own it. On the other hand is the desire to avoid something, to keep it away, reject it, renounce it, destroy it, and separate it from oneself. If we call these two poles desire and aversion, we can see more clearly that they represent the antithetical poles of taṇhā–the desire to possess and the desire to get rid of.

Unsatisfactory, unquenchable, addictive

Taṇhā is represented in the bhavacakra by a group of people drinking beer or partying. The more they drink, the more their craving keeps growing.

Ron Leifer states:

- Desire [i.e. taṇhā) causes Suffering by its own nature because it is inherently unsatisfactory. Desire means deprivation. To want something is to lack it, to be deprived of it. We do not want things we have, we only want things we don't have. Thirst is the desire for water and it occurs in the absence of water. Hunger is the feeling of lacking food. Desiring means not having, being frustrated, Suffering. Craving is Suffering. This is a most important insight, one which we drive into secrecy by our refusal to acknowledge it, thus creating the esoteric knowledge we then seek.

Most people tend to act under the assumption that if one's desires are fulfilled it will, of itself, lead to lasting happiness or well-being. However, the Buddhist teachings state that desire for conditioned things cannot be fully satiated or satisfied, due to their impermanent nature. This is expounded in the Buddhist teaching of impermanence.

Relation to the Three poisons

Taṇhā and Avidya (ignorance) can be related to the Three poisons as follows:

- Avidya (ignorance), the root of the Three poisons, is also the basis for taṇhā.

- Raga (attachment), the second of the Three poisons, is equivalent to Bhava-taṇhā (craving to be) and kāma-taṇhā (sense-craving).

- Dvesha (aversion), the third of the Three poisons, is equivalent to vibhava-taṇhā (craving not to be).

Relation to addiction

Taṇhā is sometimes related to the Western psychological concept of addiction. For example:

The Dalai Lama states:

- Much human Suffering stems from destructive emotions, as hatred breeds violence or craving fuels addiction. One of our most basic responsibilities as caring people is to alleviate the human costs of such out-of-control emotions.

Ron Leifer states:

- Obsessions, compulsions, and addictions are desires out of control, desires gone wild.

Mingyur Rinpoche states:

- Attachment is in many ways comparable to addiction, a compulsive dependency on external objects or experiences to manufacture an illusion of wholeness. Unfortunately, like other addictions, attachment becomes more intense over time.

Cessation

The third noble truth teaches that the cessation of taṇhā is possible.

- Bhikkhus, there is a noble truth about the cessation of Suffering. It is the complete fading away and cessation of this craving; its abandonment and relinquishment; getting free from and being independent of it.”

Cessation is possible by following the Noble Eightfold Path. Within this path, contemplating the impermanent nature of all things is regarded as a specific antidote to taṇhā.

Mara's daughter

Taṇhā is sometimes identified as one of Māra's three daughters, along with Arati (Boredom), and Rāga (Passion). In some accounts of The Buddha's Enlightenment, it is said that the demon Māra sent his three daughters to tempt The Buddha to give up his quest.

In a similar fashion, in Sn 436 (Saddhatissa, 1998, p. 48), taṇhā is personified as one of Death's four armies (senā) along with desire (kāmā), aversion (arati) and hunger-thirst (khuppipāsā).

Etymology

The literal meaning of taṇhā is "thirst"; however, in Buddhism it has a technical meaning described above. In part due to the variety of possible translations, taṇhā is sometimes used as an untranslated technical term by authors writing about Buddhism. One source suggests that the opposite of taṇhā is Upekkha (peace of mind, equanimity).

Smith and Novak emphasize the difficulty of translating this term; they state:

- The cause of life’s dislocation is Tanha. Again, imprecisions of translations—all are to some degree inaccurate—make it wise to stay close to the original word. Tanha is usually translated as “desire.” There is some truth in this, but if we try to make “desire” Tanha’s equivalent, we run into difficulties. To begin with, the equivalence would make this Second Truth unhelpful, for to shut down desires, all desires, in our present state would be to die, and to die is not to solve life’s problem. But beyond being unhelpful, the claim of equivalence would be flatly wrong, for there are some desires The Buddha explicitly advocated—the desire for liberation, for example, or for the happiness of others.