Difference between revisions of "The Buddha's Analysis Of Mind By U Tin U (Myaung)"

m (Text replacement - "the ages" to "the ages") |

m (Text replacement - "]]]" to "]])") |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Preface | Preface | ||

| − | About the Manuscript | + | About the {{Wiki|Manuscript}} |

| − | The present book was originally written by U Tin U (Myaung) in {{Wiki|Myanmar}} and has been published in 1999 under the title: "Myat [[Buddha]] nee kya seik ko lai lar chin". The author has translated it into English for a serialized publication in the DPPS Magazine. This manuscript comprises two portions: the typed portion is the installment contributions, 14 in number; the second portion in 41 handwritten pages is a continuation of the book. This portion has not gone to the press yet. | + | The {{Wiki|present}} [[book]] was originally written by U Tin U (Myaung) in {{Wiki|Myanmar}} and has been published in 1999 under the title: "Myat [[Buddha]] nee kya seik ko lai lar chin". The author has translated it into English for a serialized publication in the DPPS Magazine. This {{Wiki|manuscript}} comprises two portions: the typed portion is the installment contributions, 14 in number; the second portion in 41 handwritten pages is a continuation of the [[book]]. This portion has not gone to the press yet. |

The author wishes to ask for the {{Wiki|indulgence}} of the publishers to put up with the shortcomings of the script. Correctness of the entire work of course is assured. | The author wishes to ask for the {{Wiki|indulgence}} of the publishers to put up with the shortcomings of the script. Correctness of the entire work of course is assured. | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

The Author | The Author | ||

[[File:Bes-lhasa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bes-lhasa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | U TIN U retired from public service and volunteered for the [[Pitaka]] translation project launched by the {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[Pitaka]] Association (MPA) in 1981, first as a translator and later as an editor. In 1991 the MPA was voluntarily wound up and its Editorial Committee was renamed the Honorary Editorial Committee of the Department for the Promotion and [[Propagation]] of the [[Sasana]] (DPPS). U Tin U as an editor is member of the committee. He was awarded the [[religious]] title of Mahasaddhammajotikadhaja in 1998 by the State in [[recognition]] of his distinguished contribution to the [[cause]] of spreading the [[Buddha's]] [[Teaching]]. | + | U TIN U retired from public service and volunteered for the [[Pitaka]] translation project launched by the {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[Pitaka]] Association (MPA) in 1981, first as a [[translator]] and later as an editor. In 1991 the MPA was voluntarily wound up and its Editorial Committee was renamed the {{Wiki|Honorary}} Editorial Committee of the Department for the Promotion and [[Propagation]] of the [[Sasana]] (DPPS). U Tin U as an editor is member of the committee. He was awarded the [[religious]] title of [[Mahasaddhammajotikadhaja]] in 1998 by the State in [[recognition]] of his {{Wiki|distinguished}} contribution to the [[cause]] of spreading the [[Buddha's]] [[Teaching]]. |

| − | Namotassabhagavato arahato sammasambuddhassa | + | Namotassabhagavato [[arahato]] sammasambuddhassa |

Veneration to the [[Exalted One]], the Homage-worthy, the Perfectly Self-Enlightened | Veneration to the [[Exalted One]], the Homage-worthy, the Perfectly Self-Enlightened | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

THE AUTHOR'S ASPIRATION | THE AUTHOR'S ASPIRATION | ||

| − | In all humility and devotion, I pay homage to the All-knowing [[Buddha]], endowed with the eighteen kinds of' [[exceptional]] attributes, etc., and whose [[Wisdom]] must not be or cannot be fathomed ([[acinteyya]]). In consequence of this my veneration, may I be possessed of a [[mind]] that is clear, expansive and allied with {{Wiki|intelligence}}, so that I may be able to write a book on [[Mind]] ([[citta]]) as expounded in the [[Buddha's]] [[Abhidhamma]], in such intelligible expressions as would help the readers gain a good understanding of the nature and working of the [[human]] [[mind]]. And may those readers, having a [[grasp]] of the [[human]] [[mind]], each gets established in [[virtue]]. | + | In all {{Wiki|humility}} and [[devotion]], I pay homage to the All-knowing [[Buddha]], endowed with the eighteen kinds of' [[exceptional]] [[attributes]], etc., and whose [[Wisdom]] must not be or cannot be fathomed ([[acinteyya]]). In consequence of this my veneration, may I be possessed of a [[mind]] that is clear, expansive and allied with {{Wiki|intelligence}}, so that I may be able to write a [[book]] on [[Mind]] ([[citta]]) as expounded in the [[Buddha's]] [[Abhidhamma]], in such intelligible {{Wiki|expressions}} as would help the readers gain a good [[understanding]] of the [[nature]] and working of the [[human]] [[mind]]. And may those readers, having a [[grasp]] of the [[human]] [[mind]], each gets established in [[virtue]]. |

Introduction | Introduction | ||

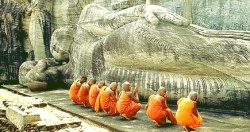

[[File:Bh11.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bh11.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Name Buddhaya siddham | + | [[Name]] [[Buddhaya]] [[siddham]] |

| − | Homage to the [[Buddha]]: success be to me! | + | Homage to the [[Buddha]]: [[success]] be to me! |

| − | It has been said that the main [[difference]] between man and [[animal]] lies in the fact that the former has {{Wiki|intelligence}}. The inference that can be drawn from this statement is that 'a man lacking in {{Wiki|intelligence}} is no better than an [[animal]].' In daily usage a dullard is often called 'a bovine species', a rather wicked epithet, but perhaps his [[stupidity]] makes him deserve such an epithet. | + | It has been said that the main [[difference]] between man and [[animal]] lies in the fact that the former has {{Wiki|intelligence}}. The {{Wiki|inference}} that can be drawn from this statement is that 'a man lacking in {{Wiki|intelligence}} is no better than an [[animal]].' In daily usage a dullard is often called 'a bovine {{Wiki|species}}', a rather wicked [[epithet]], but perhaps his [[stupidity]] makes him deserve such an [[epithet]]. |

Our main [[concern]] (or proposition) here is that a [[person]] is expected to have the normal {{Wiki|intelligence}} that a man should have. | Our main [[concern]] (or proposition) here is that a [[person]] is expected to have the normal {{Wiki|intelligence}} that a man should have. | ||

| − | As the twentieth century is drawing to a close, [[people]] are saying that [[human]] civilization has advanced in our [[world]]. Many believe that standards of living have risen. They allude this to the progress of [[Science]]. True that there have been technological innovations, almost of daily occurrence, thanks to advancements in [[science]]. In as much am marvellous technological achievements beneficial to man have been recorded, there are numerous breakthroughs in the field of mass destruction. Almost every day, awesome inventions are vying with one another, threatening mankind with [[universal]] extinction. Indeed, the [[air]] we breathe is polluted both in the [[physical]] and figurative [[senses]]. The modern man wants to boast that he is in control of the [[physical]] [[world]]. | + | As the twentieth century is drawing to a close, [[people]] are saying that [[human]] {{Wiki|civilization}} has advanced in our [[world]]. Many believe that standards of living have risen. They allude this to the progress of [[Science]]. True that there have been technological innovations, almost of daily occurrence, thanks to advancements in [[science]]. In as much am marvellous technological achievements beneficial to man have been recorded, there are numerous breakthroughs in the field of {{Wiki|mass}} destruction. Almost every day, awesome inventions are vying with one another, threatening mankind with [[universal]] [[extinction]]. Indeed, the [[air]] we [[breathe]] is polluted both in the [[physical]] and figurative [[senses]]. The {{Wiki|modern}} man wants to boast that he is in control of the [[physical]] [[world]]. |

| − | Amidst this unheard-of (so-called) 'progress', natural disasters, wherein [[human]] contribution is not yet evident, are occurring at an unprecedented rate. Meantime, inhuman {{Wiki|behaviour}} in many {{Wiki|societies}} has [[caused]] horrendous mass killings by the million among mankind. The [[death]] rate surpasses that of the last [[War]]. Such a seething state of the [[world]] today naturally befuddles the average [[person]]. He [[feels]] quite helpless. | + | Amidst this unheard-of (so-called) 'progress', natural {{Wiki|disasters}}, wherein [[human]] contribution is not yet evident, are occurring at an unprecedented rate. Meantime, inhuman {{Wiki|behaviour}} in many {{Wiki|societies}} has [[caused]] horrendous {{Wiki|mass}} killings by the million among mankind. The [[death]] rate surpasses that of the last [[War]]. Such a seething state of the [[world]] today naturally befuddles the average [[person]]. He [[feels]] quite helpless. |

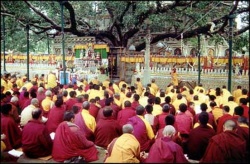

[[File:Bhikk.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bhikk.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | But where else could one find help but within himself? "Oneself is the | + | But where else could one find help but within himself? "[[Oneself is the refuge for one]]" ([[attahi attano natho]]), so said the [[Buddha]]. This [[refuge]] within oneself is none {{Wiki|ether}} than one's own [[mind]], that is, one's own [[state of mind]]. |

| − | A [[person]] with a pure and [[noble]] [[mind]] is forearmed with the fortitude to face the uneven nature of [[worldly]] [[conditions]]. So he does not pine away for his [[painful]] misfortunes. Nor does he get puffed up when highly praised. He takes the ups and downs of [[life]] merely as resultants of his past [[deeds]] and can keep his [[calm]]. He may [[feel]] a little distress under misfortune, but that is just [[human]]. He will never explode with [[anger]] or resort at foul means to assert his rights. This ability to withstand the vicissitudes of [[life]] with a proper [[attitude]], in fact, is due to the gentle [[influence]] of the [[Dhamma]] shown by the [[Buddha]]. The [[teaching]] of the [[Buddha]] in the [[form]] of the [[Three Pitakas]] have been well inherited by the peoples of {{Wiki|Myanmar}} along with other peoples who have embraced [[Theravada Buddhism]]. This deals with [[citta]] or [[mind]] which is the cornerstone of [[Abhidhamma]], one of the [[Three Pitakas]]. The [[subject]] is treated in a reasonably short manner of presentation. | + | A [[person]] with a [[pure]] and [[noble]] [[mind]] is forearmed with the fortitude to face the uneven [[nature]] of [[worldly]] [[conditions]]. So he does not pine away for his [[painful]] misfortunes. Nor does he get puffed up when highly praised. He takes the ups and downs of [[life]] merely as resultants of his {{Wiki|past}} [[deeds]] and can keep his [[calm]]. He may [[feel]] a little {{Wiki|distress}} under misfortune, but that is just [[human]]. He will never explode with [[anger]] or resort at foul means to assert his rights. This ability to withstand the vicissitudes of [[life]] with a proper [[attitude]], in fact, is due to the gentle [[influence]] of the [[Dhamma]] shown by the [[Buddha]]. The [[teaching]] of the [[Buddha]] in the [[form]] of the [[Three Pitakas]] have been well inherited by the peoples of {{Wiki|Myanmar}} along with other peoples who have embraced [[Theravada Buddhism]]. This deals with [[citta]] or [[mind]] which is the cornerstone of [[Abhidhamma]], one of the [[Three Pitakas]]. The [[subject]] is treated in a reasonably short [[manner]] of presentation. |

| − | Of the [[Three Pitakas]], [[Abhidhamma Pitaka]] surpasses the ether two in that it deals with the [[Buddha's]] [[Doctrine]] in the [[ultimate]] [[sense]], shorn of any reference to a [[person]] or place, hence it is 'special' (abhi)Dhamma. The [[Abhidhamma]] of the [[Buddha]] comprises seven books, namely: 1: [[Dhammasangani]], 2: [[Vibhanga]], 3: [[Dhatukatha]], 4: [[Puggalapannatti]], 5: Kathvatthu, 6: [[Yamaka]], 7: [[Patthana]]. These seven books in {{Wiki|Myanmar}} script of [[Pali]] are printed in 18 volumes, 12 texts as approved by the Sixth Synod, 3 Commentaries and 3 Sub-commentaries, all of them in [[Pali]]. Many of them have been translated into {{Wiki|Myanmar}}. Whether in [[Thai]] or in {{Wiki|Myanmar}} translations, these books are difficult to understand due to their abstruse and profound nature. A student needs guidance of a competent [[teacher]] to get at their meaning. | + | Of the [[Three Pitakas]], [[Abhidhamma Pitaka]] surpasses the {{Wiki|ether}} two in that it deals with the [[Buddha's]] [[Doctrine]] in the [[ultimate]] [[sense]], shorn of any reference to a [[person]] or place, hence it is 'special' ([[abhi]])[[Dhamma]]. The [[Abhidhamma]] of the [[Buddha]] comprises seven [[books]], namely: |

| + | |||

| + | 1: [[Dhammasangani]], | ||

| + | 2: [[Vibhanga]], | ||

| + | 3: [[Dhatukatha]], | ||

| + | 4: [[Puggalapannatti]], | ||

| + | 5: [[Kathvatthu]], | ||

| + | 6: [[Yamaka]], | ||

| + | 7: [[Patthana]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These seven [[books]] in {{Wiki|Myanmar}} script of [[Pali]] are printed in 18 volumes, 12 texts as approved by the Sixth Synod, 3 Commentaries and 3 Sub-commentaries, all of them in [[Pali]]. Many of them have been translated into {{Wiki|Myanmar}}. Whether in [[Thai]] or in {{Wiki|Myanmar}} translations, these [[books]] are difficult to understand due to their abstruse and profound [[nature]]. A [[student]] needs guidance of a competent [[teacher]] to get at their meaning. | ||

[[File:Heaven95.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Heaven95.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The First of the [[Abhidhamma]] books is [[Dhammasangani]] which is the very foundation of [[Abhidhamma]]. Therein the [[Buddha]] proclaims the principal outline called Matiki, which has all the [[ultimate]] [[realities]] [i.e., [[Citta]] ([[mind]]), [[cetasika]] ([[mental]] | + | The First of the [[Abhidhamma]] [[books]] is [[Dhammasangani]] which is the very foundation of [[Abhidhamma]]. Therein the [[Buddha]] proclaims the [[principal]] outline called Matiki, which has all the [[ultimate]] [[realities]] [i.e., [[Citta]] ([[mind]]), [[cetasika]] ([[mental concomitants]]), [[rupa]] ({{Wiki|matter}}) and [[Nibbana]]), each of which is grouped under three headings, and thus are called Tika [[matika]]. There are 22 such groups, the first of which is called [[Kusala]] tika. It assigns all [[ultimate]] [[realities]] to [[three classes]]: 1, [[meritorious]] [[dhamma]]; 2, [[demeritorious]] [[dhamma]]; 3, [[dhamma]] that are neither [[meritorious]] nor [[demeritorious]]. It may well be said that anyone who cannot distinguish meritoriousness and demeritoriousness is not worth having a [[human existence]]. In other words, his [[being]] born in this [[human]] [[world]] is an utter loss. This is because if, as a [[human being]], he does not knew what is [[wholesome]] [[action]] and what is [[evil]] [[action]], he is liable to blunder all through [[life]]. For the [[human]] [[mind]] usually [[feels]] at [[home]] in [[evil]]. And [[evil]] [[actions]] beget [[evil]] {{Wiki|consequences}} not only here and now, but also in the hereafter. After his [[death]] he is destined to be [[reborn]] in one of the four [[miserable]] [[existences]] of [[apaya]]. |

| − | + | Hence, anyone in his right [[senses]] should be able to distinguish between good and [[evil]]. When is the [[mind]] in a good or [[meritorious]] state? And when is it in an [[evil]] or [[demeritorious]] state? What are the [[causes]] that make the [[mind]] [[meritorious]] or [[demeritorious]]? The [[nature of mind]] is analysed in fine detail by the [[Buddha]] in his [[Abhidhamma]]. To help the man in the street get acquainted with the basic {{Wiki|principles}} of [[Abhidhamma]], a number of {{Wiki|commentarial}} {{Wiki|literature}} have been produced by learned [[theras]] of yore. The line of such {{Wiki|commentarial}} [[expositions]] thorough the ages is a long one, enriching the student's [[knowledge]] of [[Abhidhamma]]. Among the smaller commentaries the '[[Abhidhammattha sangaha]]' is [[acknowledged]] by the learned as the most reliable. It purports to provide the beginner with a condensed [[exposition]] of all that are contained in the seven [[books]] of [[Abhidhamma]]. The method of condensation is not based on each of the seven [[books]], but it is a compendium of all the facts contained in those [[books]] under suitable headings. It portrays the [[essential]] facts under nine headings, forming nine chapters, namely: | |

| + | |||

| + | l, [[Consciousness]]; | ||

| + | 2, [[Mental concomitants]]; | ||

| + | 3, Miscellaneous section; | ||

| + | 4. Analysis of Thought-processes; | ||

| + | 5, Process-freed [[Consciousness]]; | ||

| + | 6, Analysis of {{Wiki|matter}}; | ||

| + | 7, [[Abhidhamma]] categories; | ||

| + | 8, Compendium of Relations; | ||

| + | 9, [[Mental]] {{Wiki|culture}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The arrangement of [[Abhidhammattha sangaha]] is so carefully made out that it serves as a Primer of [[Abhidhamma Pitaka]]. | ||

[[File:Bhutan.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bhutan.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The present book is a study of the [[mental]] concomitants or [[cetasika]], the second chapter of the Compendium. The purpose of the book is threefold: (1) to let the student acquainted with [[mental states]], called [[mental]] concomitants, thereby making him well acquainted with [[mind]] itself; (2) to enable him to tell wrong from what is right; (3) to let him understand and cherish the [[essential]] features of {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[Buddhist]] cultural [[tradition]] that is [[rooted]] in [[Theravada Buddhism]]. An ordinary [[person]] is consumed by the eleven fires such as [[greed]], [[hatred]], bewilderment, etc., which are the [[defilements]] that arise in the [[mind]]. Whatever [[fire]] of [[defilement]] that arises in one's [[mind]] can only be quelled by the cooling water of one's purity of [[mind]]. Such [[mastery]] of one's own [[mind]] ought to be well demonstrated by us Myanmars as practising [[Buddhists]]. It is the author's sincere hope that our [[people]] may be able to show by example how to [[live]] a good, [[peaceful]] [[life]] with proper [[attitude]] of [[mind]]. | + | The {{Wiki|present}} [[book]] is a study of the [[mental]] [[concomitants]] or [[cetasika]], the second [[chapter]] of the Compendium. The {{Wiki|purpose}} of the [[book]] is threefold: (1) to let the [[student]] acquainted with [[mental states]], called [[mental]] [[concomitants]], thereby making him well acquainted with [[mind]] itself; (2) to enable him to tell wrong from what is right; (3) to let him understand and cherish the [[essential]] features of {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|cultural}} [[tradition]] that is [[rooted]] in [[Theravada Buddhism]]. An ordinary [[person]] is consumed by the eleven fires such as [[greed]], [[hatred]], [[bewilderment]], etc., which are the [[defilements]] that arise in the [[mind]]. Whatever [[fire]] of [[defilement]] that arises in one's [[mind]] can only be quelled by the cooling [[water]] of one's [[purity]] of [[mind]]. Such [[mastery]] of one's own [[mind]] ought to be well demonstrated by us [[Myanmars]] as practising [[Buddhists]]. It is the author's {{Wiki|sincere}} {{Wiki|hope}} that our [[people]] may be able to show by example how to [[live]] a good, [[peaceful]] [[life]] with proper [[attitude]] of [[mind]]. |

| − | The author of the [[Abhidhammattha sangaha]] was [[Maha]] [[Thera]] [[Anuruddha]], who resided for most of his [[life]] in the Island of Sinhala ([[Sri Lanka]]) during the period not later than the twelfth century. Records say that he was born in the town of Keveri in Kanchapura state in the province of the Cholas. Kanchipura state is called Conjiveram these days, and Keveri still is known by its old name, a seaport town at the mouth of [[River]] Keveri. It is said that [[Maha]] [[Thera]] [[Anuruddha]] wrote this book at the request of one Namba while the former was residing at the [[Mula]] [[ | + | The author of the [[Abhidhammattha sangaha]] was [[Maha]] [[Thera]] [[Anuruddha]], who resided for most of his [[life]] in the [[Island]] of [[Sinhala]] ([[Sri Lanka]]) during the period not later than the twelfth century. Records say that he was born in the town of Keveri in Kanchapura state in the province of the Cholas. Kanchipura state is called Conjiveram these days, and Keveri still is known by its old [[name]], a seaport town at the {{Wiki|mouth}} of [[River]] Keveri. It is said that [[Maha]] [[Thera]] [[Anuruddha]] wrote this [[book]] at the request of one Namba while the former was residing at the [[Mula Soma monastery]] at [[Anuradha]]. His [[book]], though small in size, has won wide acclaim. It has been translated from the original [[Pali]] into several [[languages]] including English, {{Wiki|German}}, [[Thai]], {{Wiki|Hindi}}, etc, not to mention the numerous Sub-commentaries and Expositors in [[Pali]]. |

What is [[Mind]]? | What is [[Mind]]? | ||

[[File:Heavens-gate.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Heavens-gate.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Mind]] in {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[language]] is 'Seit', an adopted word derived from the [[Pali]] word [[citta]]. There are many {{Wiki|Myanmar}} words borrowed from [[Pali]] used both in daily [[speech]] and in [[writing]]. Many of these words, when thus adopted, have their meaning changed from the original. We shall have occasion to say on this, later. | + | [[Mind]] in {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[language]] is 'Seit', an adopted [[word]] derived from the [[Pali]] [[word]] [[citta]]. There are many {{Wiki|Myanmar}} words borrowed from [[Pali]] used both in daily [[speech]] and in [[writing]]. Many of these words, when thus adopted, have their meaning changed from the original. We shall have occasion to say on this, later. |

| − | In the mean time we will dwell on [[citta]] or [[mind only]]. | + | In the mean [[time]] we will dwell on [[citta]] or [[mind only]]. |

| − | In {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[language]] we speak of someone having a good [[mind]], or a bad [[mind]]; or having a kind [[heart]]. These usages carry only [[superficial]] meanings of the word [[citta]]. To have a fair understanding of its meaning, we need to discuss about the four [[ultimate]] [[realities]] that are basic to the [[world]] and that are [[unchanging]] at all times. The four are: [[citta]] ([[mind]]), [[cetasika]] ([[mental]] concomitants), rupa (matter) and [[Nibbana]]. In [[Pali]] they are termed as [[Paramattha | + | In {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[language]] we speak of someone having a good [[mind]], or a bad [[mind]]; or having a kind [[heart]]. These usages carry only [[superficial]] meanings of the [[word]] [[citta]]. To have a fair [[understanding]] of its meaning, we need to discuss about the four [[ultimate]] [[realities]] that are basic to the [[world]] and that are [[unchanging]] at all times. The four are: [[citta]] ([[mind]]), [[cetasika]] ([[mental]] [[concomitants]]), [[rupa]] ({{Wiki|matter}}) and [[Nibbana]]. In [[Pali]] they are termed as [[Paramattha Dhamma]]. |

| − | The term [[paramattha]] is of wide significance. It also has been adopted into the {{Wiki|Myanmar}} vocabulary as ' | + | The term [[paramattha]] is of wide significance. It also has been adopted into the {{Wiki|Myanmar}} vocabulary as '[[parama]]t'. To state briefly, the [[four paramatthas]] or [[ultimate]] [[realities]] are true to their own [[nature]], not liable to change their real [[essence]]. All the [[world]] can be analysed into just these four [[ultimate]] [[realities]]; there can be no fifth one. A good [[grasp]] of the four [[ultimate]] [[realities]] is something that lies within the province of the [[wise]] ones. They are indeed abstruse. They may be considered as [[objects]] of the [[Ariya's]] [[mind]]. Since the four [[ultimate]] [[realities]] can be comprehended only through [[wisdom]], for a [[worldling]] they remain lost in [[worldly]] usage. [[Reality]] is marred by [[worldly]] usage, as if a big mountain were [[standing]] between [[reality]] and common parlance. The [[Pali]] [[word]] for common usage, i.e., the terms and [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] accepted to be true by the [[people]] at large, is [[pannatti]]. It means names or nomenclature by which [[people]] make things known. For example, a piece of land surrounded by [[water]] is called an '[[island]]' and [[people]] used the term '[[island]]' in the common [[understanding]] of that {{Wiki|concept}}. It thus becomes common usage. The [[Myanmars]] have also adopted the [[word]] [[pannatti]] as '[[pyin-nyat]]'. |

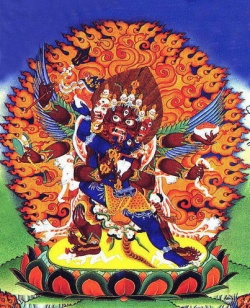

[[File:Heruka 2004.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Heruka 2004.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | So names and concepts as generally accepted are [[worldly]] [[truths]] though not [[truths]] in their [[ultimate]] [[sense]]. They cannot be disregarded. They are indispensable as media of {{Wiki|communication}}. As a matter of fact, when the [[Buddha]] expounds the [[ultimate]] [[truths]] his [[unsurpassed]] skill in [[worldly]] usage lets his hearers - be they men or [[devas]] with various inclinations, understand what the [[Buddha]] means to say. | + | So names and [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] as generally accepted are [[worldly]] [[truths]] though not [[truths]] in their [[ultimate]] [[sense]]. They cannot be disregarded. They are indispensable as media of {{Wiki|communication}}. As a {{Wiki|matter}} of fact, when the [[Buddha]] expounds the [[ultimate]] [[truths]] his [[unsurpassed]] skill in [[worldly]] usage lets his hearers - be they men or [[devas]] with various inclinations, understand what the [[Buddha]] means to say. |

| − | [[Worldly]] [[truths]] are not real [[truths]]. They are liable to | + | [[Worldly]] [[truths]] are not real [[truths]]. They are liable to change. In this connection, one is reminded of a [[wise]] remark which says: " A rose by any other [[name]] {{Wiki|smells}} as sweet." This statement points out the fact that names such as 'roses' may change where as the true quality of the rose's {{Wiki|smell}} remains [[constant]]. |

| − | What we call man, woman, dog, cow, etc., and all such terms that we use in the [[world]] belong to common usage. They lack any true [[essence]] but are mere nomenclature. They do not [[exist]] in [[truth]] and [[reality]]. What [[exist]] in [[truth]] and [[reality]] are just [[mind]] and matter, which are [[ultimate]] [[truths]]. [[Mind]] or nama in [[Pali]] refers to [[mental phenomena]] which in [[Abhidhamma]] means [[mind]] and [[mental]] concomitants. All living [[beings]], from [[Brahmas]] and [[Devas]], [[humans]] down to the tiniest insects, are mere [[compound]] things of [[mind]] and matter, having arisen due to appropriate [[causes]]. Whether in man or [[deva]] or [[brahma]] or [[animals]], there are only 28 kinds of material qualities and 89 classes of [[consciousness]] (i.e., [[mind]] or [[mental state]]). Each of these kinds or classes stands close analysis. And there are 52 kinds of [[mental]] concomitants. [[Nibbana]] is the unique [[element]] standing apart from the three other [[ultimate]] [[realities]]. This is a brief description of the four [[ultimate]] [[realities]] or [[paramattha]] [[dhammas]]. In our present [[discussion]] we are going to focus our [[attention]] on [[mind]]: how it is formed and the [[essential]] role of the [[mental]] concomitants in the arising of the states of [[mind]]. | + | What we call man, woman, {{Wiki|dog}}, {{Wiki|cow}}, etc., and all such terms that we use in the [[world]] belong to common usage. They lack any true [[essence]] but are mere nomenclature. They do not [[exist]] in [[truth]] and [[reality]]. What [[exist]] in [[truth]] and [[reality]] are just [[mind]] and {{Wiki|matter}}, which are [[ultimate]] [[truths]]. [[Mind]] or [[nama]] in [[Pali]] refers to [[mental phenomena]] which in [[Abhidhamma]] means [[mind]] and [[mental]] [[concomitants]]. All living [[beings]], from [[Brahmas]] and [[Devas]], [[humans]] down to the tiniest {{Wiki|insects}}, are mere [[compound]] things of [[mind]] and {{Wiki|matter}}, having arisen due to appropriate [[causes]]. Whether in man or [[deva]] or [[brahma]] or [[animals]], there are only 28 kinds of material qualities and 89 classes of [[consciousness]] (i.e., [[mind]] or [[mental state]]). Each of these kinds or classes stands close analysis. And there are 52 kinds of [[mental]] [[concomitants]]. [[Nibbana]] is the unique [[element]] [[standing]] apart from the three other [[ultimate]] [[realities]]. This is a brief description of the four [[ultimate]] [[realities]] or [[paramattha]] [[dhammas]]. In our {{Wiki|present}} [[discussion]] we are going to focus our [[attention]] on [[mind]]: how it is formed and the [[essential]] role of the [[mental]] [[concomitants]] in the [[arising]] of the states of [[mind]]. |

[[File:Bo1 500.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bo1 500.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Citta]] means [[consciousness]]. What is it [[conscious]] of? It is [[conscious]] of [[sense]] [[objects]]. Sense [[object]] is called [[Arammana]] in [[Pali]], which has been adopted and called 'a-yon' in {{Wiki|Myanmar}}. Great [[teachers]] of yore did not try to translate [[arammana]], lest there should occur inaccuracies in meaning. So they have simply used a like-sounding word. (Note: The [[Pali]] 'r' consonents take on the lighter and easier consonantal [[sound]] of 'y', so that although in written {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[language]], [[arammana]] is spelt as 'a-ron', in spoken [[language]] we pronounce it 'a-yon'. | + | [[Citta]] means [[consciousness]]. What is it [[conscious]] of? It is [[conscious]] of [[sense]] [[objects]]. [[Sense]] [[object]] is called [[Arammana]] in [[Pali]], which has been adopted and called 'a-yon' in {{Wiki|Myanmar}}. Great [[teachers]] of yore did not try to translate [[arammana]], lest there should occur inaccuracies in meaning. So they have simply used a like-sounding [[word]]. (Note: The [[Pali]] 'r' consonents take on the lighter and easier consonantal [[sound]] of 'y', so that although in written {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[language]], [[arammana]] is spelt as 'a-ron', in spoken [[language]] we pronounce it 'a-yon'. |

| − | Our [[people]] have long been acquainted with [[Abhidhamma]] parlance so much so that daily use of such terms as 'rupa-yon' (ruparammana), sadda-yon, gandha-yon, rasa-yon, photthabba-yon, dhammayon, for the six sense-objects have come into vogue as though they belong to our mother {{Wiki|tongue}}. Even if these terms were to be used in translation, such as eye-object, ear-object, nose-object, tongue-object, body-object and mind-object, they might [[sound]] strange to the {{Wiki|ear}} (though these are correct renderings). The hybrid Pail words (rupa-yon, etc.,) are readily accepted as the six sense-objects. Their pure vernacular terms as: [[visible | + | Our [[people]] have long been acquainted with [[Abhidhamma]] parlance so much so that daily use of such terms as '[[rupa-yon]]' ([[ruparammana]]), [[sadda-yon]], [[gandha-yon]], [[rasa-yon]], [[photthabba-yon]], [[dhammayon]], for the six [[sense-objects]] have come into vogue as though they belong to our mother {{Wiki|tongue}}. Even if these terms were to be used in translation, such as [[eye-object]], [[ear-object]], [[nose-object]], [[tongue-object]], [[body-object]] and [[mind-object]], they might [[sound]] strange to the {{Wiki|ear}} (though these are correct renderings). The hybrid Pail words ([[rupa-yon]], etc.,) are readily accepted as the six [[sense-objects]]. Their [[pure]] {{Wiki|vernacular}} terms as: [[visible objects]], [[sound]], {{Wiki|smell}}, {{Wiki|taste}}, {{Wiki|tangible}} [[object]] and [[thought]], might be used. Yet they also strike one as {{Wiki|pedantic}}. So the hybrid words ([[rupa-yon]], etc.) have become popular usage with us since the times of our forebears. |

| − | When [[consciousness]] arises, that is, when the [[mind]] becomes aware of a sense-object, other [[mental factors]] also arise together with it: they are called [[cetasika]], [[mental]] | + | When [[consciousness]] arises, that is, when the [[mind]] becomes {{Wiki|aware}} of a [[sense-object]], other [[mental factors]] also arise together with it: they are called [[cetasika]], [[mental concomitants]]. This [[word]] also has been adopted and is called ''[[cetatheik]]' which is simply a clever twist in {{Wiki|Myanmar}} {{Wiki|Orthography}}. |

| − | There are four characteristic properties of a [[cetasika]], namely: | + | There are four [[characteristic]] properties of a [[cetasika]], namely: |

i: [[Cetasika]] arises together with [[consciousness]]; | i: [[Cetasika]] arises together with [[consciousness]]; | ||

| Line 81: | Line 103: | ||

ii: It perishes together with [[consciousness]]; | ii: It perishes together with [[consciousness]]; | ||

| − | iii: It has an identical [[object]] with [[consciousness]]; | + | iii: It has an [[identical]] [[object]] with [[consciousness]]; |

iv: It has a common basis with [[consciousness]]. | iv: It has a common basis with [[consciousness]]. | ||

| Line 87: | Line 109: | ||

2. The Seven 'Universals' | 2. The Seven 'Universals' | ||

| − | There are seven [[mental]] | + | There are seven [[mental concomitants]] or [[cetasika]] that are common to every [[consciousness]]: they are: |

| + | |||

| + | (1) [[Contact]] ([[phassa]]), | ||

| + | (2) [[Sensation]] ([[vedana]]), | ||

| + | (3) [[Perception]] ([[sanna]]), | ||

| + | [[Volition]] ([[cetana]]) , | ||

| + | (5) [[One-pointedness of mind]] ([[ekaggata]]), | ||

| + | (6) Faculty of [[life]] ([[jivitindriya]]) and | ||

| + | [[Attention]] ([[manasikara]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | They are invariably {{Wiki|present}} in all types of [[consciousness]]. They bear, so to speak, {{Wiki|equal}} {{Wiki|responsibility}} for the [[arising]] of any [[consciousness]]. Hence they are called 'Universals' or [[sabbacittasadharana cetasika]]. We shall now take up each of their roles. | ||

| − | 3. [[Phassa]] can draw tears. | + | 3. [[Phassa]] can draw {{Wiki|tears}}. |

(1) [[Contact]] - [[Phassa]] | (1) [[Contact]] - [[Phassa]] | ||

[[File:Bodhgaya-1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bodhgaya-1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Contact]] means touch. But it is not between matter and matter, but it is between [[mind]] and matter, and therefore is of deep significance in the arising of [[consciousness]]. It refers to the impact between [[mind]] and matter. It is through this impact that the [[mind]] is drawn to a sense-object. Without the functioning of [[contact]], the [[mind]] cannot become aware of any sense-object. [[Contact]] therefore is impingement on the sense-base. Due to the impingement, there is a coincidence of the sense-object, the appropriate sense-base, and [[consciousness]] that makes the [[mind]] aware of the [[object]]. | + | [[Contact]] means {{Wiki|touch}}. But it is not between {{Wiki|matter}} and {{Wiki|matter}}, but it is between [[mind]] and {{Wiki|matter}}, and therefore is of deep significance in the [[arising]] of [[consciousness]]. It refers to the impact between [[mind]] and {{Wiki|matter}}. It is through this impact that the [[mind]] is drawn to a [[sense-object]]. Without the functioning of [[contact]], the [[mind]] cannot become {{Wiki|aware}} of any [[sense-object]]. [[Contact]] therefore is impingement on the sense-base. Due to the impingement, there is a coincidence of the [[sense-object]], the appropriate sense-base, and [[consciousness]] that makes the [[mind]] {{Wiki|aware}} of the [[object]]. |

| − | [[Contact]] thus brings together the [[consciousness]] (that has eye-sensitivity or the the [[eye]] as its basis) and the [[visible]] [[object]]. Herein, eye-sensitivity [[element]] is materiality, and so also is [[visible]] [[object]]. Due to the coordinating function of [[contact]], [[eye-consciousness]], that has its base in eye-sensitivity [[element]], arises. The [[awareness]] of the [[visible]] [[object]] by the [[eye-consciousness]] takes place. In common parlance, the [[eye]] sees the [[object]]. The arising of [[eye-consciousness]] is brought about by [[contact]], (that has eye-sensitivity [[element]], i.e., the [[eye]], as its base) between [[eye]] and [[visible]] [[object]]. | + | [[Contact]] thus brings together the [[consciousness]] (that has eye-sensitivity or the the [[eye]] as its basis) and the [[visible]] [[object]]. Herein, eye-sensitivity [[element]] is [[materiality]], and so also is [[visible]] [[object]]. Due to the coordinating [[function]] of [[contact]], [[eye-consciousness]], that has its base in eye-sensitivity [[element]], arises. The [[awareness]] of the [[visible]] [[object]] by the [[eye-consciousness]] takes place. In common parlance, the [[eye]] sees the [[object]]. The [[arising]] of [[eye-consciousness]] is brought about by [[contact]], (that has eye-sensitivity [[element]], i.e., the [[eye]], as its base) between [[eye]] and [[visible]] [[object]]. |

| − | In like manner, the [[consciousness]] that is based on the ear-sensitivity [[element]] (the {{Wiki|ear}}) is made aware of a [[sound]] by [[contact]] that has ear-sensitivity [[element]] as its base. Thus there arises [[ear-consciousness]]. | + | In like [[manner]], the [[consciousness]] that is based on the ear-sensitivity [[element]] (the {{Wiki|ear}}) is made {{Wiki|aware}} of a [[sound]] by [[contact]] that has ear-sensitivity [[element]] as its base. Thus there arises [[ear-consciousness]]. |

| − | The [[consciousness]] that is based on the nose-sensitivity [[element]] (the {{Wiki|nose}}) is made aware of a smell by [[contact]] that has nose-sensitivity [[element]] as its base. Thus there arises [[nose-consciousness]]. | + | The [[consciousness]] that is based on the [[nose]]-sensitivity [[element]] (the {{Wiki|nose}}) is made {{Wiki|aware}} of a {{Wiki|smell}} by [[contact]] that has nose-sensitivity [[element]] as its base. Thus there arises [[nose-consciousness]]. |

| − | The [[consciousness]] that is based on the tongue-sensitivity [[element]] (the {{Wiki|tongue}}) is made aware of a {{Wiki|taste}} by [[contact]] that has tongue-sensitivity [[element]] as its base. Thus there arises [[tongue-consciousness]]. | + | The [[consciousness]] that is based on the [[tongue]]-sensitivity [[element]] (the {{Wiki|tongue}}) is made {{Wiki|aware}} of a {{Wiki|taste}} by [[contact]] that has tongue-sensitivity [[element]] as its base. Thus there arises [[tongue-consciousness]]. |

[[File:Heruka-Vajrakilaya.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Heruka-Vajrakilaya.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The [[consciousness]] that is based on the body-sensitivity [[element]] (the [[body]]) is made aware of a tangible [[object]] by [[contact]] that has body-sensitivity [[element]] as its base. Thus there arises body-consciousness. | + | The [[consciousness]] that is based on the [[body]]-sensitivity [[element]] (the [[body]]) is made {{Wiki|aware}} of a {{Wiki|tangible}} [[object]] by [[contact]] that has body-sensitivity [[element]] as its base. Thus there arises [[body-consciousness]]. |

| − | The five [[physical]] organs , i.e., [[eye]], {{Wiki|ear}}, {{Wiki|nose}}, {{Wiki|tongue}} and [[body]] , each has its own sensitivity [[element]]. Appropriate [[consciousness]] and their [[mental]] | + | The five [[physical]] {{Wiki|organs}} , i.e., [[eye]], {{Wiki|ear}}, {{Wiki|nose}}, {{Wiki|tongue}} and [[body]] , each has its own sensitivity [[element]]. Appropriate [[consciousness]] and their [[mental concomitants]] enter through their respective sensitivity [[elements]], which thereby serve as doors for such entry. So the sensitivity [[elements]] are also referred to as 'doors' ([[dvara]]). Beside these [[sense doors]], there is also a separate [[mental phenomena]] which is the mind-sensitivity [[element]] serving as the door for [[mind-objects]] to enter. This [[mind-door]] which has the [[heart]] or [[hadayavatthu]] as its base is made {{Wiki|aware}} of [[mind-objects]] including various [[thoughts]] and [[ideas]] by [[contact]] that has the [[heart]] or [[hadayavatthu]] as its base. Thus there arises [[mind-consciousness]]. |

| − | [[Contact]] that arises at its appropriate sense-door is called samphassa. There are six samphassa for the six doors, namely: Cakkhu-samphassa (eye-contact), sota-samphassa (ear-contact), ghana-samphassa (nose-contact), jivha-samphassa (tongue-contact), Kaya-samphassa (body-contact) and mano-samphassa (mind-contact). | + | [[Contact]] that arises at its appropriate [[sense-door]] is called [[samphassa]]. There are six [[samphassa]] for the [[six doors]], namely: [[Cakkhu-samphassa]] ([[eye-contact]]), [[sota-samphassa]] ([[ear-contact]]), [[ghana-samphassa]] ([[nose-contact]]), [[jivha-samphassa]] ([[tongue-contact]]), [[Kaya-samphassa]] ([[body-contact]]) and [[mano-samphassa]] ([[mind-contact]]). |

| − | The [[mental]] | + | The [[mental concomitant]] of [[phassa]] impinges on its relevant sense-base with great impact. It is common [[knowledge]] through personal [[experience]] that when you see someone relishing some [[sour]] eatable (like lime, etc.) your {{Wiki|mouth}} waters by the mere [[sight]] of it. This is how [[phassa]] can be very potent. Similarly, when talented actors play their parts well in a tragic scene, either on the stage or on the screen, the audience, overwhelmed by the pathos of the scene, find it hard to control their {{Wiki|tears}}. This is another common instance of the [[power]] of [[phassa]]. |

[[File:Bodhgaya01.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bodhgaya01.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

(2) [[Sensation]], [[Vedana]] | (2) [[Sensation]], [[Vedana]] | ||

| − | [[Sensation]] is how you [[feel]] in your [[mind]] or how the [[mind]] reacts to sense-objects. When the [[mind]] comes into [[contact]] with any one of the six kinds of sense-objects, it may find it agreeable, or disagreeable, or neither agreeable nor disagreeable. Roughly speaking, these three kinds of [[sensations]] usually arise. When the [[object]] is agreeable, there arises a [[pleasant]] [[sensation]]; when it is disagreeable, an [[unpleasant]] [[sensation]] arises; when it is neither agreeable nor disagreeable, a [[neutral]] [[sensation]] arises. These three kinds of the way one [[feels]] about sense-objects is the characteristic of [[vedana]]. Whenever a [[consciousness]] arises, [[vedana]] or [[sensation]] invariably arises. [[Sensation]] is of six kinds depending on the sense-doors of its arising. Hence there are these six kinds of | + | [[Sensation]] is how you [[feel]] in your [[mind]] or how the [[mind]] reacts to [[sense-objects]]. When the [[mind]] comes into [[contact]] with any one of the six kinds of [[sense-objects]], it may find it agreeable, or [[disagreeable]], or neither agreeable nor [[disagreeable]]. Roughly {{Wiki|speaking}}, these three kinds of [[sensations]] usually arise. When the [[object]] is agreeable, there arises a [[pleasant]] [[sensation]]; when it is [[disagreeable]], an [[unpleasant]] [[sensation]] arises; when it is neither agreeable nor [[disagreeable]], a [[neutral]] [[sensation]] arises. These three kinds of the way one [[feels]] about [[sense-objects]] is the [[characteristic]] of [[vedana]]. Whenever a [[consciousness]] arises, [[vedana]] or [[sensation]] invariably arises. [[Sensation]] is of six kinds depending on the [[sense-doors]] of its [[arising]]. Hence there are these [[six kinds of sensation born of contact]] ([[samphassajavedana]]) |

| − | Cakkhusamphassajavedana ([[sensation | + | [[Cakkhusamphassajavedana]] ([[sensation born of eye-contact]]) |

| − | sotasamphassajavedana ([[sensation | + | [[sotasamphassajavedana]] ([[sensation born of ear-contact]]) |

| − | manosamphassajavedana ([[sensation | + | [[manosamphassajavedana]] ([[sensation born of mind-contact]]). |

(Note: 'ja' is the shortened [[form]] of 'jati'='born of') | (Note: 'ja' is the shortened [[form]] of 'jati'='born of') | ||

| Line 125: | Line 157: | ||

(3) [[Perception]] ([[Sanna]]) | (3) [[Perception]] ([[Sanna]]) | ||

[[File:Heruka-vg.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Heruka-vg.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | On coming into [[contact]] with a sense-object, the [[mind]] perceives it, that is to say, it notes it as to its colour such as: “This is white, this is red, or this is green.” It notes it as to its former shape such as : “This is round, this is flat or this is soft, this is hard and so on. This is called [[cognition]] of an [[object]]. Once the [[mind]] has [[perceived]] or [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognized]] an [[object]], it recognizes it as it has [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognized]] on noted. A child who has everything around him to {{Wiki|cognize}}, and which he is able to recognize. [[Sanna]] means simple sense-perception, the [[cognition]] of a child. It does not know about what the [[object]] actually is. It does not know the ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ about it. But the [[sense]] [[perception]] lasts, so that it enables one to recognize the [[object]] that has once been [[perceived]]. Repeated [[recognition]] of an [[object]] as such and such makes the [[mind]] [[conscious]] of it, like [[phassa]] and [[vedana]], that makes the [[mind]] [[conscious]] of an [[object]]. [[Sanna]] is called by the [[object]] it perceives - not by the sense-door. | + | On coming into [[contact]] with a [[sense-object]], the [[mind]] [[perceives]] it, that is to say, it notes it as to its {{Wiki|colour}} such as: “This is white, this is red, or this is green.” It notes it as to its former shape such as : “This is round, this is flat or this is soft, this is hard and so on. This is called [[cognition]] of an [[object]]. Once the [[mind]] has [[perceived]] or [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognized]] an [[object]], it [[recognizes]] it as it has [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognized]] on noted. A child who has everything around him to {{Wiki|cognize}}, and which he is able to [[recognize]]. [[Sanna]] means simple [[sense-perception]], the [[cognition]] of a child. It does not know about what the [[object]] actually is. It does not know the ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ about it. But the [[sense]] [[perception]] lasts, so that it enables one to [[recognize]] the [[object]] that has once been [[perceived]]. Repeated [[recognition]] of an [[object]] as such and such makes the [[mind]] [[conscious]] of it, like [[phassa]] and [[vedana]], that makes the [[mind]] [[conscious]] of an [[object]]. [[Sanna]] is called by the [[object]] it [[perceives]] - not by the [[sense-door]]. |

Thus there are six kinds of [[Perception]]; | Thus there are six kinds of [[Perception]]; | ||

| Line 133: | Line 165: | ||

2. [[Saddasanna]]=the [[Perception]] of a [[sound]], | 2. [[Saddasanna]]=the [[Perception]] of a [[sound]], | ||

| − | 3. [[Gandhasanna]]=the [[Perception]] of a smell, | + | 3. [[Gandhasanna]]=the [[Perception]] of a {{Wiki|smell}}, |

4. [[Rasasanna]]=the [[Perception]] of a {{Wiki|taste}}, | 4. [[Rasasanna]]=the [[Perception]] of a {{Wiki|taste}}, | ||

| − | 5. [[Photthabbasana]]=the [[Perception]] of a tangible [[object]], and | + | 5. [[Photthabbasana]]=the [[Perception]] of a {{Wiki|tangible}} [[object]], and |

[[File:BQlyGTX.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:BQlyGTX.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | 6. [[Dhammasanna]]=the [[Perception]] of a mind-object. | + | 6. [[Dhammasanna]]=the [[Perception]] of a [[mind-object]]. |

(4) Why [[Cetana]] is called [[Kamma]]? | (4) Why [[Cetana]] is called [[Kamma]]? | ||

| Line 145: | Line 177: | ||

4. [[Volition]] ([[Cetana]]) | 4. [[Volition]] ([[Cetana]]) | ||

| − | [[Cetana]] motivates, impels, prompts or induces the [[mental states]] associated with itself to the [[object]] of [[consciousness]]. Thus it acts as co-ordinator of its allied [[mental]] | + | [[Cetana]] motivates, impels, prompts or induces the [[mental states]] associated with itself to the [[object]] of [[consciousness]]. Thus it acts as co-ordinator of its allied [[mental concomitants]]. It acts as an efficient team-leader, like a {{Wiki|carpenter}} who fulfills his duties and regulates the work of others as well. It acts on its associates and sees to the [[accomplishment]] of the task. Thus it determines [[action]]. For this [[reason]] the [[Buddha]] says that [[cetana]] is called [[kamma]]. |

[[Cetana]] is classified according to the [[object]], and there are six classes of [[cetana]] ([[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volitions]]): | [[Cetana]] is classified according to the [[object]], and there are six classes of [[cetana]] ([[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volitions]]): | ||

| Line 151: | Line 183: | ||

1. [[Rupasancetana]] with regard to [[visible]] [[objects]], | 1. [[Rupasancetana]] with regard to [[visible]] [[objects]], | ||

| − | 2. [[Saddasancetana]] with regard to sounds, | + | 2. [[Saddasancetana]] with regard to {{Wiki|sounds}}, |

| − | 3. [[Gandhasancetana]] with regard to smells, | + | 3. [[Gandhasancetana]] with regard to {{Wiki|smells}}, |

| − | 4. [[Rasasancetana]] with regard to tastes, | + | 4. [[Rasasancetana]] with regard to {{Wiki|tastes}}, |

[[File:Heruka015.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Heruka015.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | 5. [[Photthabbasancetana]] with regard to tangible [[objects]] and | + | 5. [[Photthabbasancetana]] with regard to {{Wiki|tangible}} [[objects]] and |

| − | 6. [[Manosancetana]] with regard to mind-objects. | + | 6. [[Manosancetana]] with regard to [[mind-objects]]. |

(5) [[One-pointedness of Mind]], [[Ekaggata]] | (5) [[One-pointedness of Mind]], [[Ekaggata]] | ||

| − | [[Ekaggata]] means focusing the [[mind]] on an [[object]]. So it means [[concentration]]. [[Ekaggata]] with regard to an [[evil]] [[mind]] is called [[Evil]] [[concentration]]. For example, when the [[mind]] is [[concentrated]] on fishing ( or angling), it is [[evil]] [[concentration]]. When the [[mind]] is [[concentrated]] on an [[object]] of [[meditation]], it is [[right concentration]] or sammasamadhi. | + | [[Ekaggata]] means focusing the [[mind]] on an [[object]]. So it means [[concentration]]. [[Ekaggata]] with regard to an [[evil]] [[mind]] is called [[Evil]] [[concentration]]. For example, when the [[mind]] is [[concentrated]] on fishing ( or angling), it is [[evil]] [[concentration]]. When the [[mind]] is [[concentrated]] on an [[object]] of [[meditation]], it is [[right concentration]] or [[sammasamadhi]]. |

(6) Faculty of [[Life]], [[Jivitindriya]] | (6) Faculty of [[Life]], [[Jivitindriya]] | ||

| − | The author of the [[Abhidhammatthasangha]] says that “[[Life]] is the Faculty.” The [[Pali]] word [[Jivitindriya]] is a [[compound]] of Jivita ([[life]]) + [[indriya]] (faculty). This terms has two aspects: by [[jivita]] it connotes that it sustains its associates; by [[indriya]] it connotes that it controls its associates. What the author of the compendium means in the aforesaid statement is [[Jivitindriya]] controls [[life]] through its sustenance. A living [[being]] is [[essentially]] a [[compound]] thin of [[mind]] and matter. Material [[life]] is controlled or kept alive by [[Rupajivitindriya]] and [[mental]] [[life]] is controlled or kept alive by [[Namajivitindriya]]. Since we are discussing about [[mental phenomena]], we are concerned with [[Namajivitindriya]] here. [[Rupajivita]] sustains [[life]] from the moment of conception till the moment of [[death]]. When the [[kamma]]-born corporeality ceases it becomes lifeless. It is due to the ceasing of [[Rupajivitindriya]]. That is called the [[death]] of the living [[being]]. As for [[Namajivitindriya]], it does not perish at the moment of [[death]] of the [[person]]. It continues to function in its three phases of its [[existence]], i.e., the arising moment, the momentarily static moment, and the perishing moment ([[uppada]], [[thiti]], [[bhanga]]), after the arising of the [[death]]-[[consciousness]]. The three-phased [[thought]] process immediately follows the [[death]]-[[consciousness]] as | + | The author of the [[Abhidhammatthasangha]] says that “[[Life]] is the Faculty.” The [[Pali]] [[word]] [[Jivitindriya]] is a [[compound]] of [[Jivita]] ([[life]]) + [[indriya]] ({{Wiki|faculty}}). This terms has two aspects: by [[jivita]] it connotes that it sustains its associates; by [[indriya]] it connotes that it controls its associates. What the author of the compendium means in the aforesaid statement is [[Jivitindriya]] controls [[life]] through its [[sustenance]]. A living [[being]] is [[essentially]] a [[compound]] thin of [[mind]] and {{Wiki|matter}}. Material [[life]] is controlled or kept alive by [[Rupajivitindriya]] and [[mental]] [[life]] is controlled or kept alive by [[Namajivitindriya]]. Since we are discussing about [[mental phenomena]], we are concerned with [[Namajivitindriya]] here. [[Rupajivita]] sustains [[life]] from the moment of {{Wiki|conception}} till the moment of [[death]]. When the [[kamma]]-born corporeality ceases it becomes lifeless. It is due to the ceasing of [[Rupajivitindriya]]. That is called the [[death]] of the living [[being]]. As for [[Namajivitindriya]], it does not perish at the moment of [[death]] of the [[person]]. It continues to [[function]] in its three phases of its [[existence]], i.e., the [[arising]] moment, the momentarily static moment, and the perishing moment ([[uppada]], [[thiti]], [[bhanga]]), after the [[arising]] of the [[death]]-[[consciousness]]. The three-phased [[thought]] process immediately follows the [[death]]-[[consciousness]] as ([[[re-birth]] [[consciousness]])] of the succeeding [[existence]], due to the functioning of the [[Relation]] of Contiguity ([[Anantara]] + [[Paccaya]]).* The [[Namajivitindriya]] thus keeps on from [[existence]] to [[existence]] until such [[time]] as the living [[being]] attains final [[Nibbana]] when [[mind]] and {{Wiki|matter}} come to [[cessation]]. Viewed in this way, [[Jivitindriya]] is the [[principal]] [[mental concomitant]]. Just as the [[lotus]] is kept alive by the [[water]], [[mental states]] are sustained by [[Namajivitindriya]]. It is the [[mental]] [[phenomenon]] that gives continuity to countless [[existence]]. This [[phenomenon]] ([[arising]] due to [[kamma]] at each fresh state of [[existence]]) is not understood by those outside the [[Theravada]] [[Teaching]]. They believe it to be a living [[entity]] called the [[soul]] or the [[life]] or the [[spirit]]. |

(7) [[Attention]], [[Manisikara]] | (7) [[Attention]], [[Manisikara]] | ||

| Line 175: | Line 207: | ||

There are three kinds of [[Manisikara]], but we are not immediately concerned with them here. * Please [[Ledi Sayadaw]]: [[Patthanuddesa dipani]]. | There are three kinds of [[Manisikara]], but we are not immediately concerned with them here. * Please [[Ledi Sayadaw]]: [[Patthanuddesa dipani]]. | ||

| − | Thus far we have briefly discussed about the seven [[Universal]] [[mental]] | + | Thus far we have briefly discussed about the seven [[Universal]] [[mental concomitants]] that invariably arise with [[consciousness]]. These seven ‘Universals,’ ‘[[phassa]], [[vedana]], [[Sanna]], [[cetana]], [[ekaggata]], [[jivitindriya]] and [[manisikara]]’ arise dependent on [[consciousness]], and [[consciousness]] arises due to their [[arising]]. Therefore as Causal Relations, [[Patthana]], they are mutually [[conditioned]] by [[consciousness]]. All [[consciousness]] without exception arise simultaneously with these seven [[mental concomitants]]. All of them play {{Wiki|equal}} parts in all types of [[consciousness]]. Hence, they are called ‘Universals.’ In [[Abhidhammatthasangaha]] they are termed as [[Sabbacittasadharana cetasika]] ([[mental concomitants]] having {{Wiki|equal}} {{Wiki|responsibility}} in all types of [[consciousness]].) |

(Note: The {{Wiki|Myanmar}} Acronyms for the seven [[Pali]] terms, meant for helping the student’s [[memory]], are omitted here.) | (Note: The {{Wiki|Myanmar}} Acronyms for the seven [[Pali]] terms, meant for helping the student’s [[memory]], are omitted here.) | ||

| − | 5. [[Meritorious | + | 5. [[Meritorious consciousness]] and [[Demeritorius consciousness]] |

Having understood how [[consciousness]] arises, we shall now consider how a good [[mind]] arises and also how a bad [[mind]] arises. | Having understood how [[consciousness]] arises, we shall now consider how a good [[mind]] arises and also how a bad [[mind]] arises. | ||

| − | The principle according to [[Abhidhamma]] distinguishing good and bad [[minds]] is not only natural but also is acceptable by peoples professing various [[faiths]]. The [[Buddha]] lays down that: | + | The [[principle]] according to [[Abhidhamma]] distinguishing [[good and bad]] [[minds]] is not only natural but also is acceptable by peoples professing various [[faiths]]. The [[Buddha]] lays down that: |

| − | A good [[action]] is blameless because it does not harm either oneself or another and therefore it is called [[meritorious]]. | + | A good [[action]] is [[blameless]] because it does not harm either oneself or another and therefore it is called [[meritorious]]. |

| − | A bad [[action]] is blameworthy because it [[causes]] harm either to oneself or to another and therefore it is called [[demeritorious]]. (Note: [[action]] here means and include all [[verbal]] [[actions]], i.e., [[speech]] as well as other forms of [[verbal]] expression.) | + | A bad [[action]] is blameworthy because it [[causes]] harm either to oneself or to another and therefore it is called [[demeritorious]]. (Note: [[action]] here means and include all [[verbal]] [[actions]], i.e., [[speech]] as well as other [[forms]] of [[verbal]] expression.) |

| − | The [[conscious]] [[mind]] by its own nature just [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognizes]] the six sense-objects. It is the associate [[mental states]] or concomitants which arise under various circumstances that [[condition]] the [[mind]] how it [[feels]] about these [[objects]], such as whether a certain [[object]] is agreeable or disagreeable. For example, in [[seeing]] a [[visible]] [[object]], the [[mind]] is made to [[form]] its opinion whether it likes the [[object]], or dislike it, whether it [[feels]] agreeable or disagreeable. At that moment, by the aforesaid criteria of good or bad as declared by the [[Buddha]], blameworthy, i.e., [[demeritorious]], [[consciousness]] may arise. The [[mind]] which is naturally colourless is thus tainted black by the [[demeritorious]] [[mental]] | + | The [[conscious]] [[mind]] by its own [[nature]] just [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognizes]] the six [[sense-objects]]. It is the associate [[mental states]] or [[concomitants]] which arise under various circumstances that [[condition]] the [[mind]] how it [[feels]] about these [[objects]], such as whether a certain [[object]] is agreeable or [[disagreeable]]. For example, in [[seeing]] a [[visible]] [[object]], the [[mind]] is made to [[form]] its opinion whether it likes the [[object]], or dislike it, whether it [[feels]] agreeable or [[disagreeable]]. At that moment, by the aforesaid criteria of good or bad as declared by the [[Buddha]], blameworthy, i.e., [[demeritorious]], [[consciousness]] may arise. The [[mind]] which is naturally colourless is thus [[tainted]] black by the [[demeritorious]] [[mental concomitants]]. Likewise, it may be tinged with the beautiful colours of the [[meritorious]] [[mental concomitants]]. In [[doctrinal]] parlance, [[demeritorious]] [[mental]] [[conditions]] are called 'white'. Thus, there arises either a [[demeritorious]] [[consciousness]] or a [[meritorious]] [[consciousness]], due to the [[nature]] of the [[mental concomitants]]. |

| − | Hence it should be noted that the natural factors that [[cause]] either a good [[mind]] or a bad [[mind]] are the [[mental]] | + | Hence it should be noted that the natural factors that [[cause]] either a good [[mind]] or a bad [[mind]] are the [[mental concomitants]] that are associated with the [[mind]]. All states of [[mind]] belonging to the [[Buddha]] or to any living [[being]] are classified under [[three categories]] in [[Abhidhamma]]. |

| − | + | The three are: | |

| − | + | 1. [[Meritorious consciousness]], [[Kusala Dhamma]], | |

| + | 2. [[Demeritorious consciousness]], [[Akusala Dhamma]], and | ||

| + | 3. Neither [[Meritorious]] nor [[Demeritorious]], [[Abyakata Dhamma]]. | ||

| − | + | Everyone of us is experiencing the [[influence]] of either [[meritorious]] or [[demeritorious consciousness]] at all our waking moments. If we can tell the bad from the good in our [[mental states]], we shall be able to lead blames [[lives]], much to our [[benefit]]. Therefore let us discuss what [[dhammas]] are [[meritorious]] and what [[dhammas]] are [[demeritorious]]. | |

| − | In [[Abhidhammatthasangaha]] six particular [[mental]] | + | We have discussed the seven 'universals' that invariably arise together with [[consciousness]]. We will now deal with the six kinds of 'particular' [[mental concomitants]] that arose together particularly with [[meritorious]] [[consciousness]], or particularly with [[demeritorious consciousness]]. In [[Pali]] they are termed as [[Pakinnakacetasika]] whose literal meaning is , 'of mixed [[character]].' What this term connotes is that they mix with [[meritorious consciousness]] and thereby become associates of meritoriousness; or they also mix with [[demeritorious consciousness]] and thereby become associates of demeritoriousness. Old [[masters]] have adopted the [[Pali]] term as a hybrid called 'Pakein.' We will now describe these [[six 'Particular]]' [[mental concomitants]]. |

| + | |||

| + | 6. The [[six 'Particular]]' [[Cetasikas]] or the 'Six Mixers' | ||

| + | |||

| + | In [[Abhidhammatthasangaha]] six particular [[mental concomitants]] are termed as [[Pakinnaka Cetasika]] because they are found both in [[meritorious]] [[consciousness]] and [[demeritorious consciousness]]. When they arise together with [[meritorious consciousness]], they become [[meritorious]]; When they arise together with [[demeritorious consciousness]], they become [[demeritorious]]. They are called [[pakinnaka]] because they are associated either with [[meritorious consciousness]] or [[demeritorious consciousness]], as the case may be. They are not associated with all the [[89 types of consciousness]], but only with certain of them in particular cases. When and how the six become associates of either [[meritorious]] or [[demeritorious]] will become clear when we take them up individually. The [[six Pakinnakas]] ('[[Particulars]]') are: [[Vitakka]], [[Vicara]], [[Adhimokha]], [[Viriya]], [[Piti]] and [[Chanda]]. | ||

(1) Initial Appliication of [[Mind]] ([[Vitakka]]) | (1) Initial Appliication of [[Mind]] ([[Vitakka]]) | ||

| − | The [[Pali]] term [[Vitakka]] has been generally called 'vitak' in hybrid {{Wiki|Myanmar}}. It is [[thinking]] about the [[object]]. It repeatedly [[thinks]] about the [[object]]. The [[object]] may be a [[meritorious]] one or a [[demeritorious]] one. The role of [[Vitakka]] is very important in the arising of [[consciousness]]. It 'lifts up' the [[mind]] onto the [[object]], that is, all the [[mental]] | + | The [[Pali]] term [[Vitakka]] has been generally called '[[vitak]]' in hybrid {{Wiki|Myanmar}}. It is [[thinking]] about the [[object]]. It repeatedly [[thinks]] about the [[object]]. The [[object]] may be a [[meritorious]] one or a [[demeritorious]] one. The role of [[Vitakka]] is very important in the [[arising]] of [[consciousness]]. It 'lifts up' the [[mind]] onto the [[object]], that is, all the [[mental concomitants]] are made to apply on the [[object]]. |

| − | A [[person]] has an endless variety of [[objects]] to think about. So, to conduct all the associated [[mental states]] to a particular [[object]] is not an easy matter. The straying of one's [[thoughts]] can be observed when at [[dead]] of night a [[person]] is apt to be [[thinking]] about an endless string of matters. When this happens [[sleep]] does not come to him. Applying the [[mind]] to a certain [[object]] is a [[vital]] step in [[meditation]]. The [[yogi]] comes to understand the straying nature of the [[mind]]. [[Vitakka]] has to see that all the [[mental]] | + | A [[person]] has an [[endless]] variety of [[objects]] to think about. So, to conduct all the associated [[mental states]] to a particular [[object]] is not an easy {{Wiki|matter}}. The straying of one's [[thoughts]] can be observed when at [[dead]] of night a [[person]] is apt to be [[thinking]] about an [[endless]] string of matters. When this happens [[sleep]] does not come to him. Applying the [[mind]] to a certain [[object]] is a [[vital]] step in [[meditation]]. The [[yogi]] comes to understand the straying [[nature]] of the [[mind]]. [[Vitakka]] has to see that all the [[mental concomitants]] apply on the [[object]] of [[meditations]], say, on [[inbreaths]] and [[outbreaths]]. It requires really earnest [[effort]] to achieve this. |

| − | Vittaka is the forerunner of [[concentration]] of [[mind]]. When (the first) [[jhana]] is attained [[Vitakka]] is counted as the first of the five factors of [[Jhana]]. Not only is [[Vitakka]] recognised as the significant factor in [[Jhana]] practice, it is also an important constituent of the [[Ariya]] [[Path]] of Eight Constituents known as | + | [[Vittaka]] is the forerunner of [[concentration]] of [[mind]]. When (the first) [[jhana]] is [[attained]] [[Vitakka]] is counted as the first of the five factors of [[Jhana]]. Not only is [[Vitakka]] recognised as the significant factor in [[Jhana]] practice, it is also an important constituent of the [[Ariya]] [[Path]] of Eight Constituents known as [[Right Thinking]] ([[Sammasankappa]]) in [[Insight]] [[Meditation]] leading to [[Magga]]. |

(The five factors of [[Jhana]]: [[Vitakka]], [[Vicara]], [[Piti]], [[Sukha]] and [[Ekaggata]]) | (The five factors of [[Jhana]]: [[Vitakka]], [[Vicara]], [[Piti]], [[Sukha]] and [[Ekaggata]]) | ||

| Line 213: | Line 251: | ||

(2) Sustained Application of [[Mind]], [[Vicara]] | (2) Sustained Application of [[Mind]], [[Vicara]] | ||

| − | Once [[Vitakka]] has put the [[mind]] securely on the [[object]], [[Vicara]] takes over the continued exercise of the [[mind]] on the [[object]]. [[Vicara]] examines its [[object]] and thereby remains constant on it without wandering away. [[Vitakka]] strives to apply the [[mental]] | + | Once [[Vitakka]] has put the [[mind]] securely on the [[object]], [[Vicara]] takes over the continued exercise of the [[mind]] on the [[object]]. [[Vicara]] examines its [[object]] and thereby remains [[constant]] on it without wandering away. [[Vitakka]] strives to apply the [[mental concomitants]] on the [[object]]. The straying [[mind]] is made to apply itself on the [[meditation]] [[object]] of [[inbreaths]] and [[outbreaths]]. When the striving of [[Vitakka]] is fulfilled, the [[mind]] is engaged in examining the [[object]] which is the task of [[Vicara]]. At this stage [[Vitakka's]] role becomes insignificant. The {{Wiki|examination}} gains significance. The old [[teachers]] speak of [[Vitakka]] and [[Vicara]] together. This is because both of these two [[mental concomitants]] play the role of steadying the [[mind]] on the [[object]]. [[Vitakka]] initially trains the [[mind]]; it is in itself a tough exercise. [[Vicara]] sustains its hold of the [[object]] which is a relatively smooth exercise. The {{Wiki|distinction}} between these two stages is likened to the [[sound]] produced when a [[pagoda]]-[[bell]] is [[being]] struck. At the moment of the striking the [[sound]] is loud and harsh. This is like [[Vitakka]]'s [[effort]]. Later on, only the reverberation is heard. This is like Vicara's [[effort]]. To take another example, when an aircraft takes off, its engines roar, like the tough struggle of [[Vitakka]]. When the aircraft has taken off, only the gentle whirr of the engines can be heard, like the steadied [[mind]] resting on its [[object]]. |

Of the five factors of [[Jhana]], [[Vicara]] is the second factor after [[Vitakka]]. When we compare their {{Wiki|individual}} tasks in exercising the [[mind]], at the stage of the [[second jhana]], the task of [[Vitakka]] is no longer necessary when [[Vicara]] has taken over. Hence it should be noted that at the stage of the [[second jhana]], only four [[jhanic]] factors remain. | Of the five factors of [[Jhana]], [[Vicara]] is the second factor after [[Vitakka]]. When we compare their {{Wiki|individual}} tasks in exercising the [[mind]], at the stage of the [[second jhana]], the task of [[Vitakka]] is no longer necessary when [[Vicara]] has taken over. Hence it should be noted that at the stage of the [[second jhana]], only four [[jhanic]] factors remain. | ||

| − | (3) Decision, [[Adhimokkha]] | + | (3) [[Decision]], [[Adhimokkha]] |

| − | [[Adhimokkha]] means decision. Literally, it 'releases the [[mind]] onto the [[object]]'. It is making the choice in the [[sense]] that the [[mind]] is not allowed to stray away but is kept firmly on the [[object]]. So it is opposed to wavering ([[Vicikiccha]]). It makes a firm conclusion (sannitthana). Various [[religious]] [[faiths]] prevail in the [[world]] due to the [[power]] of [[Adhimokkha]]. | + | [[Adhimokkha]] means [[decision]]. Literally, it 'releases the [[mind]] onto the [[object]]'. It is making the choice in the [[sense]] that the [[mind]] is not allowed to stray away but is kept firmly on the [[object]]. So it is opposed to wavering ([[Vicikiccha]]). It makes a firm conclusion (sannitthana). Various [[religious]] [[faiths]] prevail in the [[world]] due to the [[power]] of [[Adhimokkha]]. |

(4) [[Effort]], [[Viriya]] | (4) [[Effort]], [[Viriya]] | ||

| − | [[Viriya]] has been adopted in its original [[Pali]] [[form]] in its [[Abhidhamma]] [[sense]]. It is [[effort]]. Like an energetic [[person]] who exerts his [[influence]] on his associates to get something done. [[Viriya]] lends support to its associated [[mental states]] and sustains all the joint efforts. It serves as new pillars that support an old house. [[Viriya]] is indispensable either for the success of a [[worthy]] undertaking or an [[evil]] undertaking. When it is associated with meritoriousness, it is called Sammavayama, a [[Path]] Factor. When associated with demeritoriousness, it is called Micchavayama. | + | [[Viriya]] has been adopted in its original [[Pali]] [[form]] in its [[Abhidhamma]] [[sense]]. It is [[effort]]. Like an energetic [[person]] who exerts his [[influence]] on his associates to get something done. [[Viriya]] lends support to its associated [[mental states]] and sustains all the joint efforts. It serves as new pillars that support an old house. [[Viriya]] is indispensable either for the [[success]] of a [[worthy]] {{Wiki|undertaking}} or an [[evil]] {{Wiki|undertaking}}. When it is associated with meritoriousness, it is called Sammavayama, a [[Path]] Factor. When associated with demeritoriousness, it is called Micchavayama. |

(5) Delightful [[Sensation]] ([[Piti]]) | (5) Delightful [[Sensation]] ([[Piti]]) | ||

| − | [[Piti]] is the [[mental]] | + | [[Piti]] is the [[mental concomitant]] that gives one delightful [[sensation]] in the [[object]]. It permeates the whole [[body]]. One who has [[Piti]] finds the task in hand very [[interesting]] and satisfying, {{Wiki|forgetting}} tiredness and hunger. Athletes in {{Wiki|training}} are sustained by [[Piti]]. Consider the weight-lifters struggling with their leaded bars. Also consider the professional boxers who allow themselves to be pounded at by a {{Wiki|training}} partner who is of about {{Wiki|equal}} skill and {{Wiki|weight}} with him. Onlookers might [[feel]] sorry for their [[pain]] and trouble, but the trainees themselves get [[satisfaction]] from their [[pleasant]] exercise. Among lovers, any hardship or trouble involved in their efforts to [[pleased]] their beloved partners is a source of [[joy]] and [[pleasure]] for them. Such instances are of course commonplace. |

| + | |||

| + | Hence it should be noted that the natural factors that [[cause]] either a good [[mind]] or a bad [[mind]] are the [[mental concomitants]] that are associated with the [[mind]]. All states of [[mind]] belonging to the [[Buddha]] or to any living [[being]] are classified under [[three categories]] in [[Abhidhamma]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The three are: | ||

| − | + | 1. [[Meritorious consciousness]], [[Kusala Dhamma]], | |

| + | 2. [[Demeritorious consciousness]], [[Akusala Dhamma]], and | ||

| + | 3. [[Neither Meritorious nor Demeritorious]], [[Abyakata Dhamma]]. | ||

| − | Everyone of us is experiencing the [[influence]] of either [[meritorious]] or [[demeritorious]] [[consciousness]] at all our waking moments. If we can tell the bad from the good in our [[mental states]], we shall be able to lead blames [[lives]], much to our benefit. Therefore let us discuss what [[dhammas]] are [[meritorious]] and what [[dhammas]] are [[demeritorious]]. | + | Everyone of us is experiencing the [[influence]] of either [[meritorious]] or [[demeritorious]] [[consciousness]] at all our waking moments. If we can tell the bad from the good in our [[mental states]], we shall be able to lead blames [[lives]], much to our [[benefit]]. Therefore let us discuss what [[dhammas]] are [[meritorious]] and what [[dhammas]] are [[demeritorious]]. |

| − | We have discussed the seven 'universals' that invariably arise together with [[consciousness]]. We will now deal with the six kinds of 'particular' [[mental]] | + | We have discussed the seven 'universals' that invariably arise together with [[consciousness]]. We will now deal with the six kinds of 'particular' [[mental concomitants]] that arose together particularly with [[meritorious consciousness]], or particularly with [[de-meritorious consciousness]]. In [[Pali]] they are termed as [[Pakinnakacetasika]] whose literal meaning is , 'of mixed [[character]].' What this term connotes is that they mix with [[meritorious consciousness]] and thereby become associates of meritoriousness; or they also mix with [[demeritorious consciousness]] and thereby become associates of demeritoriousness. Old [[masters]] have adopted the [[Pali]] term as a hybrid called 'Pakein.' We will now describe these [[six 'Particular]]' [[mental concomitants[[. |

(6) The Way to be , [[Chanda]] | (6) The Way to be , [[Chanda]] | ||

| − | [[Chanda]] can be rendered as the will to be or the will to do. It is not just [[desire]] to get something, which is called [[attachment]]. [[Attachment]] is characteristic of [[craving]] ([[Lobha]]), which is a [[demeritorious]] [[state of mind]]. Commentaries explain [[Chanda]] as simple wish to do. This wish is divested of [[attachment]]. [[Attachment]] or [[craving]] is [[essentially]] [[greed]]. [[Chanda]] however is a [[noble]] [[aspiration]]. Making a wish is also called expressing one's [[aspiration]]. The wish or [[aspiration]] is to do something good, to become good, or to attain some goal. It is free from the defiling [[mental state]], the sticky taint of [[craving]]. There are two types of wishing - the [[meritorious]] or righteous wish called sammachanda. The [[evil]] wish of the elephant queen Cula [[Subhadda]] praying before a [[paccekabuddha]] that she would be able to kill the elephant king Chaddanta is a micchachanda. | + | [[Chanda]] can be rendered as the will to be or the will to do. It is not just [[desire]] to get something, which is called [[attachment]]. [[Attachment]] is [[characteristic]] of [[craving]] ([[Lobha]]), which is a [[demeritorious]] [[state of mind]]. Commentaries explain [[Chanda]] as simple wish to do. This wish is divested of [[attachment]]. [[Attachment]] or [[craving]] is [[essentially]] [[greed]]. [[Chanda]] however is a [[noble]] [[aspiration]]. Making a wish is also called expressing one's [[aspiration]]. The wish or [[aspiration]] is to do something good, to become good, or to attain some goal. It is free from the defiling [[mental state]], the sticky taint of [[craving]]. There are two types of wishing - the [[meritorious]] or righteous wish called sammachanda. The [[evil]] wish of the [[elephant]] [[Wikipedia:Queen consort|queen]] Cula [[Subhadda]] praying before a [[paccekabuddha]] that she would be able to kill the [[elephant]] [[king]] [[Chaddanta]] is a micchachanda. |

| − | 7. [[Mental]] | + | 7. [[Mental Concomitants]] that are common to each other, [[Annasamana Cetasika]] |

| − | The seven 'Universals' and the six 'Particulars' (described above), these 13 [[mental]] | + | The seven 'Universals' and the [[six 'Particulars]]' (described above), these 13 [[mental concomitants]] may be associated with either meritoriousness or demeritoriousness. Therefore they are called [[Annasamana]] [[cetasika]] in [[Abhidhammatthasangaha]]. This [[Pali]] term has also been adopted as a hybrid {{Wiki|Myanmar}} [[word]] called '[[annyasamann]]' by a clever twist in {{Wiki|orthography}}. These 13 [[mental concomitants]] are to be considered as '[[being]] one or the other', i.e., they become [[meritorious]] when associated or combined with [[meritorious]] [[thought]], or [[demeritorious]] when associated or combined with [[demeritorious]] [[thoughts]]. This is a simplified explanation of [[annasamana]], whose literal meaning is rather difficult to understand. Thus they work both ways, as [[meritorious]] factors or [[demeritorious]] factors, according to which side they become associated with. |

| − | Before proceeding to [[meritorious]] and [[demeritorious]] [[mental]] | + | Before proceeding to [[meritorious]] and [[demeritorious]] [[mental concomitants]], we shall take a short review these 13 [[mental concomitants]] called '[[annyasamann]]' in {{Wiki|Myanmar}}, which are of [[vital]] importance in the [[arising]] of [[thoughts]]. |

| − | The Thirteen | + | The Thirteen [[Annasamana Cetasika]] |

| − | (a) The 7 'Universals' (sabbacittasadharana): | + | (a) The [[7 'Universals]]' ([[sabbacittasadharana]]): |

1. [[Phassa]], [[contact]], impingement | 1. [[Phassa]], [[contact]], impingement | ||

| Line 259: | Line 303: | ||

5. [[Ekkagata]], [[one-pointedness of mind]], [[concentration]] | 5. [[Ekkagata]], [[one-pointedness of mind]], [[concentration]] | ||

| − | 6. [[Jivitindriya]], faculty of [[life]] | + | 6. [[Jivitindriya]], {{Wiki|faculty}} of [[life]] |

7. [[Manisikara]], [[attention]] | 7. [[Manisikara]], [[attention]] | ||

| − | The seven [[mental]] | + | The seven [[mental concomitants]] may become associates of any [[meritorious]] [[thought]], as the case may be. Or they may become associates of any [[demeritorious]] [[thought]], as the case may be. Thus the Universals are invariably associated with all classes of [[consciousness]]. Hence they are included in all the 89 classes of [[consciousness]]. (In a more elaborate {{Wiki|classification}}, they belong to the 121 classes of [[consciousness]]). |