Difference between revisions of "Xuanzang or Hsüan-tsang"

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Xuan-zang-2sd.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuan-zang-2sd.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | '''[[Xuanzang]]''' (pronounced Shwan-dzang ) was a famous {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhist monk]], [[scholar]], traveler, and translator that brought up the interaction between [[China]] and [[India]] in the early Tang period. | + | '''[[Xuanzang]]''' (pronounced Shwan-dzang ) was a famous {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhist monk]], [[scholar]], traveler, and [[translator]] that brought up the interaction between [[China]] and [[India]] in the early [[Tang period]]. |

He became famous for his seventeen year overland trip to [[India]] and back, which is recorded in detail in his autobiography and a {{Wiki|biography}}. | He became famous for his seventeen year overland trip to [[India]] and back, which is recorded in detail in his autobiography and a {{Wiki|biography}}. | ||

{{Wiki|Nomenclature}}, {{Wiki|orthography}} and {{Wiki|etymology}} | {{Wiki|Nomenclature}}, {{Wiki|orthography}} and {{Wiki|etymology}} | ||

| − | [[Xuanzang]] is also known as Táng-sānzàng (唐三藏) or simply as Táng Sēng (唐僧), or Tang (Dynasty) [[Monk]] in Mandarin; in Cantonese as Tong Sam Jong and in [[Vietnamese]] as Đường Tam Tạng . Less common romanizations of [[Xuanzang]] include Hhuen Kwan, [[Hiouen Thsang]], Hiuen Tsiang, Hsien-tsang, Hsyan-tsang, Hsuan Chwang, Hsuan Tsiang, Hwen Thsang, Xuan Cang, [[Xuan Zang]], Shuen [[Shang]], Yuan Chang, Yuan Chwang, and Yuen Chwang . Hsüan, Hüan, Huan and Chuang are also found. In [[Korean]], he is known as Hyeon Jang . In [[Japanese]], he is known as Genjō , or Genjō-sanzō (Xuanzang-sanzang). In [[Vietnamese]], he is known as Đường Tăng (Tang [[Buddhist monk]]), Đường Tam Tạng ("Tang [[Tripitaka]]" [[monk]]), Huyền Trang (the Han-Vietnamese [[name]] of [[Xuanzang]] ) | + | [[Xuanzang]] is also known as Táng-sānzàng ([[唐三藏]]) or simply as [[Táng Sēng]] ([[唐僧]]), or Tang ([[Dynasty]]) [[Monk]] in [[Wikipedia:Mandarin Chinese|Mandarin]]; in [[Cantonese]] as Tong Sam Jong and in [[Vietnamese]] as [[Đường Tam Tạng]] . Less common romanizations of [[Xuanzang]] include [[Hhuen Kwan]], [[Hiouen Thsang]], [[Hiuen Tsiang]], [[Hsien-tsang]], [[Hsyan-tsang]], [[Hsuan Chwang]], [[Hsuan Tsiang]], [[Hwen Thsang]], Xuan {{Wiki|Cang}}, [[Xuan Zang]], [[Shuen]] [[Shang]], [[Yuan]] [[Chang]], [[Yuan Chwang]], and [[Yuen Chwang]] . [[Hsüan]], [[Hüan]], [[Huan]] and [[Chuang]] are also found. In [[Korean]], he is known as Hyeon [[Jang]] . In [[Japanese]], he is known as [[Genjō]] , or [[Genjō-sanzō]] (Xuanzang-sanzang). In [[Vietnamese]], he is known as [[Đường Tăng]] (Tang [[Buddhist monk]]), [[Đường Tam Tạng]] ("Tang [[Tripitaka]]" [[monk]]), [[Huyền Trang]] (the Han-Vietnamese [[name]] of [[Xuanzang]] ) |

[[File:Xuanzang w.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang w.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Sānzàng (三藏) is the {{Wiki|Chinese}} term for the [[Tripitaka]] [[scriptures]], and in some English-language fiction he is addressed with this title. | + | [[Sānzàng]] ([[三藏]]) is the {{Wiki|Chinese}} term for the [[Tripitaka]] [[scriptures]], and in some English-language {{Wiki|fiction}} he is addressed with this title. |

Early [[life]] | Early [[life]] | ||

| − | [[Xuanzang]] was born near Luoyang, Henan in 602? as Chén Huī or Chén Yī (陳 褘) and [[died]] 5th Feb. 664 in Yu Hua [[Gong]] (玉華宮). [[Xuanzang]], whose lay [[name]] was Chen Hui, was born into a family noted for its erudition for generations. He was the youngest of four children. His great-grandfather was an official serving as a prefect, his grandfather was appointed as {{Wiki|professor}} in the Imperial College at the {{Wiki|capital}}. His father was a conservative Confucianist who gave up office and withdrew into {{Wiki|seclusion}} to escape the {{Wiki|political}} turmoil that gripped [[China]] at that [[time]]. According to [[traditional]] {{Wiki|biographies}}, [[Xuanzang]] displayed a superb [[intelligence]] and earnestness, amazing his father by his careful [[observance]] of the {{Wiki|Confucian}} [[rituals]] at the age of eight. Along with his brothers and sister, he received an early [[education]] from his father, who instructed him in classical works on filial piety and several other {{Wiki|canonical}} treatises of {{Wiki|orthodox}} {{Wiki|Confucianism}}. | + | [[Xuanzang]] was born near [[Luoyang]], {{Wiki|Henan}} in 602? as [[Chén Huī]] or [[Chén Yī]] ([[陳]] 褘) and [[died]] 5th Feb. 664 in Yu Hua [[Gong]] ([[玉華宮]]). [[Xuanzang]], whose lay [[name]] was [[Chen Hui]], was born into a [[family]] noted for its erudition for generations. He was the youngest of four children. His great-grandfather was an official serving as a prefect, his grandfather was appointed as {{Wiki|professor}} in the {{Wiki|Imperial}} {{Wiki|College}} at the {{Wiki|capital}}. His father was a conservative {{Wiki|Confucianist}} who gave up office and withdrew into {{Wiki|seclusion}} to escape the {{Wiki|political}} turmoil that gripped [[China]] at that [[time]]. According to [[traditional]] {{Wiki|biographies}}, [[Xuanzang]] displayed a superb [[intelligence]] and earnestness, amazing his father by his careful [[observance]] of the {{Wiki|Confucian}} [[rituals]] at the age of eight. Along with his brothers and sister, he received an early [[education]] from his father, who instructed him in classical works on filial piety and several other {{Wiki|canonical}} treatises of {{Wiki|orthodox}} {{Wiki|Confucianism}}. |

| − | Although his household in Chenhe Village of Goushi Town (緱氏 gou1), Luo Prefecture (洛州), Henan, was [[essentially]] {{Wiki|Confucian}}, at a young age [[Xuanzang]] expressed [[interest]] in becoming a [[Buddhist monk]] as one of his elder brothers had done. After the [[death]] of his father in 611, he lived with his older brother Chensu (later known as Changjie) for five years at [[Jingtu]] [[Monastery]] (淨土寺) in Luoyang, supported by the Sui Dynasty state. During this [[time]] he studied both [[Theravada]] and [[Mahayana Buddhism]], preferring the latter. | + | Although his household in Chenhe Village of Goushi Town (緱氏 gou1), Luo Prefecture (洛州), {{Wiki|Henan}}, was [[essentially]] {{Wiki|Confucian}}, at a young age [[Xuanzang]] expressed [[interest]] in becoming a [[Buddhist monk]] as one of his elder brothers had done. After the [[death]] of his father in 611, he lived with his older brother Chensu (later known as [[Changjie]]) for five years at [[Jingtu]] [[Monastery]] ([[淨土寺]]) in [[Luoyang]], supported by the {{Wiki|Sui Dynasty}} [[state]]. During this [[time]] he studied both [[Theravada]] and [[Mahayana Buddhism]], preferring the [[latter]]. |

| − | In 618, the Sui Dynasty collapsed and [[Xuanzang]] and his brother fled to Chang'an, which had been proclaimed as the {{Wiki|capital}} of the Tang state, and thence southward to Chengdu, {{Wiki|Sichuan}}. Here the two brothers spent two or three years in further study in the [[monastery]] of Kong Hui, including the Abhidharmakosa-sastra ([[Abhidharma]] Storehouse Treatise). When [[Xuanzang]] requested to take [[Buddhist]] orders at the age of thirteen, the [[abbot]] Zheng Shanguo made an exception in his case [[because of]] his precocious [[knowledge]]. | + | In 618, the {{Wiki|Sui Dynasty}} collapsed and [[Xuanzang]] and his brother fled to [[Chang'an]], which had been proclaimed as the {{Wiki|capital}} of the Tang [[state]], and thence southward to {{Wiki|Chengdu}}, {{Wiki|Sichuan}}. Here the two brothers spent two or three years in further study in the [[monastery]] of [[Kong Hui]], [[including]] the [[Abhidharmakosa-sastra]] ([[Abhidharma]] [[Storehouse]] Treatise). When [[Xuanzang]] requested to take [[Buddhist]] orders at the age of thirteen, the [[abbot]] [[Zheng Shanguo]] made an exception in his case [[because of]] his precocious [[knowledge]]. |

[[File:Xuanzang Da Yan Ta statue.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang Da Yan Ta statue.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Xuanzang]] was fully [[ordained]] as a [[monk]] in 622, at the age of twenty. The myriad contradictions and discrepancies in the texts at that [[time]] prompted [[Xuanzang]] to decide to go to [[India]] and study in the cradle of [[Buddhism]]. He subsequently left his brother and returned to Chang'an to study foreign [[languages]] and to continue his study of [[Buddhism]]. He began his [[mastery]] of [[Sanskrit]] in 626, and probably also studied Tocharian. During this [[time]] [[Xuanzang]] also became [[interested]] in the [[metaphysical]] [[Yogacara]] school of [[Buddhism]]. | + | [[Xuanzang]] was fully [[ordained]] as a [[monk]] in 622, at the age of twenty. The {{Wiki|myriad}} contradictions and discrepancies in the texts at that [[time]] prompted [[Xuanzang]] to decide to go to [[India]] and study in the cradle of [[Buddhism]]. He subsequently left his brother and returned to [[Chang'an]] to study foreign [[languages]] and to continue his study of [[Buddhism]]. He began his [[mastery]] of [[Sanskrit]] in 626, and probably also studied [[Tocharian]]. During this [[time]] [[Xuanzang]] also became [[interested]] in the [[metaphysical]] [[Yogacara]] school of [[Buddhism]]. |

[[Pilgrimage]] | [[Pilgrimage]] | ||

| − | In 629, [[Xuanzang]] reportedly had a [[dream]] that convinced him to journey to [[India]]. The {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} and Eastern Türk Göktürks were waging [[war]] at the [[time]]; therefore [[Emperor]] Tang Taizong prohibited foreign travel. [[Xuanzang]] persuaded some [[Buddhist]] guards at the gates of Yumen and slipped out of the [[empire]] via Liangzhou ( Gansu), and {{Wiki|Qinghai}} province. He subsequently travelled across the {{Wiki|Gobi Desert}} to Kumul (Hami), thence following the Tian Shan westward, arriving in Turfan in 630. Here he met the [[king]] of Turfan, a [[Buddhist]] who equipped him further for his travels with letters of introduction and valuables to serve as funds. | + | In 629, [[Xuanzang]] reportedly had a [[dream]] that convinced him to journey to [[India]]. The {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} and Eastern Türk {{Wiki|Göktürks}} were waging [[war]] at the [[time]]; therefore [[Emperor]] [[Tang Taizong]] prohibited foreign travel. [[Xuanzang]] persuaded some [[Buddhist]] guards at the gates of [[Yumen]] and slipped out of the [[empire]] via [[Liangzhou]] ( [[wikipedia:Gansu|Gansu]]), and {{Wiki|Qinghai}} province. He subsequently travelled across the {{Wiki|Gobi Desert}} to [[Kumul]] ([[Hami]]), thence following the [[Tian Shan]] westward, arriving in [[Turfan]] in 630. Here he met the [[king]] of [[Turfan]], a [[Buddhist]] who equipped him further for his travels with letters of introduction and valuables to serve as funds. |

| − | Moving further westward, [[Xuanzang]] escaped robbers to reach Yanqi, then toured the [[Theravada]] [[monasteries]] of [[Kucha]]. Further {{Wiki|west}} he passed Aksu before turning {{Wiki|northwest}} to cross the Tian Shan's Bedal Pass into {{Wiki|modern}} Kyrgyzstan. He skirted Issyk Kul before visiting Tokmak on its {{Wiki|northwest}}, and met the great {{Wiki|Khan}} of the Western Türk, whose relationship to the Tang [[emperor]] was friendly at the [[time]]. After a feast, [[Xuanzang]] continued {{Wiki|west}} then {{Wiki|southwest}} to Tashkent (Chach/Che-Shih), {{Wiki|capital}} of {{Wiki|modern}} day [[Uzbekistan]]. From here, he crossed the desert further {{Wiki|west}} to Samarkand. In Samarkand, which was under Persian [[influence]], the party came across some abandoned [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] and [[Xuanzang]] impressed the local [[king]] with his preaching. Setting out again to the {{Wiki|south}}, [[Xuanzang]] crossed a spur of the Pamirs and passed through the famous Iron Gates. Continuing southward, he reached the Amu Darya and Termez, where he encountered a community of more than a thousand [[Buddhist]] [[monks]]. | + | Moving further westward, [[Xuanzang]] escaped {{Wiki|robbers}} to reach [[Yanqi]], then toured the [[Theravada]] [[monasteries]] of [[Kucha]]. Further {{Wiki|west}} he passed {{Wiki|Aksu}} before turning {{Wiki|northwest}} to cross the [[Tian Shan's]] Bedal Pass into {{Wiki|modern}} [[Kyrgyzstan]]. He skirted [[Issyk Kul]] before visiting [[Tokmak]] on its {{Wiki|northwest}}, and met the great {{Wiki|Khan}} of the {{Wiki|Western}} Türk, whose relationship to the Tang [[emperor]] was friendly at the [[time]]. After a feast, [[Xuanzang]] continued {{Wiki|west}} then {{Wiki|southwest}} to [[Tashkent]] ([[Chach/Che-Shih]]), {{Wiki|capital}} of {{Wiki|modern}} day [[Uzbekistan]]. From here, he crossed the desert further {{Wiki|west}} to {{Wiki|Samarkand}}. In {{Wiki|Samarkand}}, which was under [[Persian]] [[influence]], the party came across some abandoned [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] and [[Xuanzang]] impressed the local [[king]] with his preaching. Setting out again to the {{Wiki|south}}, [[Xuanzang]] crossed a spur of the [[Pamirs]] and passed through the famous [[Iron Gates]]. Continuing southward, he reached the [[Amu Darya]] and Termez, where he encountered a {{Wiki|community}} of more than a thousand [[Buddhist]] [[monks]]. |

[[File:Xuanzang0012.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang0012.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Further {{Wiki|east}} he passed through Kunduz, where he stayed for some [[time]] to {{Wiki|witness}} the [[funeral]] [[rites]] of {{Wiki|Prince}} Tardu, who had been poisoned. Here he met the [[monk]] Dharmasimha, and on the advice of the late Tardu made the trip westward to Balkh ({{Wiki|modern}} day {{Wiki|Afghanistan}}), to see the [[Buddhist]] sites and [[relics]], especially the Nava [[Vihara]], or Nawbahar, which he described as the westernmost [[monastic]] institution in the [[world]]. Here [[Xuanzang]] also found over 3,000 [[Theravada]] [[monks]], including Prajnakara, a [[monk]] with whom [[Xuanzang]] studied [[Theravada]] [[scriptures]]. He acquired the important [[[Mahāvibhāṣa]]] text here, which he later translated into {{Wiki|Chinese}}. Prajnakara then accompanied the party southward to Bamyan, where [[Xuanzang]] met the [[king]] and saw tens of [[Theravada]] [[monasteries]], in addition to the two large Bamyan [[Buddhas]] carved out of the rockface. The party then resumed their travel eastward, crossing the Shibar pass and descending to the regional {{Wiki|capital}} of Kapisi (about 60 km {{Wiki|north}} of {{Wiki|modern}} {{Wiki|Kabul}}), which sported over 100 [[monasteries]] and 6,000 [[monks]], mostly [[Mahayana]]. This was part of the fabled old land of [[Gandhara]]. [[Xuanzang]] took part in a [[religious]] [[debate]] here, and demonstrated his [[knowledge]] of many [[Buddhist]] sects. Here he also met the first {{Wiki|Jains}} and [[Hindus]] of his journey. He pushed on to Jalalabad and Laghman, where he considered himself to have reached [[India]]. The year was 630. | + | Further {{Wiki|east}} he passed through [[Kunduz]], where he stayed for some [[time]] to {{Wiki|witness}} the [[funeral]] [[rites]] of {{Wiki|Prince}} [[Tardu]], who had been poisoned. Here he met the [[monk]] Dharmasimha, and on the advice of the late [[Tardu]] made the trip westward to [[Balkh]] ({{Wiki|modern}} day {{Wiki|Afghanistan}}), to see the [[Buddhist]] sites and [[relics]], especially the Nava [[Vihara]], or [[Nawbahar]], which he described as the westernmost [[monastic]] institution in the [[world]]. Here [[Xuanzang]] also found over 3,000 [[Theravada]] [[monks]], [[including]] [[Prajnakara]], a [[monk]] with whom [[Xuanzang]] studied [[Theravada]] [[scriptures]]. He acquired the important [[[Mahāvibhāṣa]]] text here, which he later translated into {{Wiki|Chinese}}. [[Prajnakara]] then accompanied the party southward to [[Bamyan]], where [[Xuanzang]] met the [[king]] and saw tens of [[Theravada]] [[monasteries]], in addition to the two large [[Bamyan]] [[Buddhas]] carved out of the rockface. The party then resumed their travel eastward, crossing the [[Shibar pass]] and descending to the regional {{Wiki|capital}} of Kapisi (about 60 km {{Wiki|north}} of {{Wiki|modern}} {{Wiki|Kabul}}), which sported over 100 [[monasteries]] and 6,000 [[monks]], mostly [[Mahayana]]. This was part of the fabled old land of [[Gandhara]]. [[Xuanzang]] took part in a [[religious]] [[debate]] here, and demonstrated his [[knowledge]] of many [[Buddhist]] sects. Here he also met the first {{Wiki|Jains}} and [[Hindus]] of his journey. He pushed on to Jalalabad and Laghman, where he considered himself to have reached [[India]]. The year was 630. |

{{Wiki|South}} {{Wiki|Asia}} | {{Wiki|South}} {{Wiki|Asia}} | ||

| − | [[Xuanzang]] left Jalalabad, which had few [[Buddhist]] [[monks]], but many [[stupas]] and [[monasteries]]. He passed through Hunza and the Khyber Pass to the {{Wiki|east}}, reaching the former {{Wiki|capital}} of [[Gandhara]], on the other side. {{Wiki|Peshawar}} was [[nothing]] compared to its former glory, and [[Buddhism]] was declining in the region. [[Xuanzang]] visited a number of [[stupas]] around {{Wiki|Peshawar}}, notably the [[Kanishka]] [[Stupa]]. This [[stupa]] was built just {{Wiki|southeast}} of {{Wiki|Peshawar}}, by a former [[king]] of the city. In 1908 it was rediscovered by D.B. Spooner with the help of [[Xuanzang's]] account. | + | [[Xuanzang]] left Jalalabad, which had few [[Buddhist]] [[monks]], but many [[stupas]] and [[monasteries]]. He passed through [[Hunza]] and the Khyber Pass to the {{Wiki|east}}, reaching the former {{Wiki|capital}} of [[Gandhara]], on the other side. {{Wiki|Peshawar}} was [[nothing]] compared to its former glory, and [[Buddhism]] was declining in the region. [[Xuanzang]] visited a number of [[stupas]] around {{Wiki|Peshawar}}, notably the [[Kanishka]] [[Stupa]]. This [[stupa]] was built just {{Wiki|southeast}} of {{Wiki|Peshawar}}, by a former [[king]] of the city. In 1908 it was rediscovered by D.B. Spooner with the help of [[Xuanzang's]] account. |

| − | [[Xuanzang]] left {{Wiki|Peshawar}} and travelled {{Wiki|northeast}} to the {{Wiki|Swat}} Valley. Reaching [[Udyana]], he found 1,400 old [[monasteries]], that had previously supported 18,000 [[monks]]. The remnant [[monks]] were of the [[Mahayana]] school. [[Xuanzang]] continued northward and into the Buner Valley, before doubling back via Shabaz Gharni to cross the {{Wiki|Indus}} [[river]] at Hund. Thereafter he headed to {{Wiki|Taxila}}, a [[Mahayana]] [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|kingdom}} that was a vassal of [[Kashmir]], which is precisely where he headed next. Here he found 5,000 more [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] in 100 [[monasteries]]. Here he met a talented [[Mahayana]] [[monk]] and spent his next two years (631-633) studying [[Mahayana]] alongside other [[schools of Buddhism]]. During this [[time]], [[Xuanzang]] writes about the [[Fourth Buddhist council]] that took place nearby, ca. 100 AD, under the [[order]] of [[King]] [[Kanishka]] of Kushana. | + | [[Xuanzang]] left {{Wiki|Peshawar}} and travelled {{Wiki|northeast}} to the {{Wiki|Swat}} Valley. Reaching [[Udyana]], he found 1,400 old [[monasteries]], that had previously supported 18,000 [[monks]]. The remnant [[monks]] were of the [[Mahayana]] school. [[Xuanzang]] continued northward and into the Buner Valley, before doubling back via Shabaz Gharni to cross the {{Wiki|Indus}} [[river]] at [[Hund]]. Thereafter he headed to {{Wiki|Taxila}}, a [[Mahayana]] [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|kingdom}} that was a vassal of [[Kashmir]], which is precisely where he headed next. Here he found 5,000 more [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] in 100 [[monasteries]]. Here he met a talented [[Mahayana]] [[monk]] and spent his next two years (631-633) studying [[Mahayana]] alongside other [[schools of Buddhism]]. During this [[time]], [[Xuanzang]] writes about the [[Fourth Buddhist council]] that took place nearby, ca. 100 AD, under the [[order]] of [[King]] [[Kanishka]] of [[Kushana]]. |

[[File:Xuanzang79.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang79.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

In 633, [[Xuanzang]] left [[Kashmir]] and journeyed {{Wiki|south}} to Chinabhukti ([[thought]] to be {{Wiki|modern}} Firozpur), where he studied for a year with the monk-prince Vinitaprabha. | In 633, [[Xuanzang]] left [[Kashmir]] and journeyed {{Wiki|south}} to Chinabhukti ([[thought]] to be {{Wiki|modern}} Firozpur), where he studied for a year with the monk-prince Vinitaprabha. | ||

| − | In 634 he went {{Wiki|east}} to Jalandhar in eastern Punjab, before climbing up to visit predominantly " [[Hinayana]]" [[monasteries]] in the {{Wiki|Kulu}} valley and turning southward again to Bairat and then {{Wiki|Mathura}}, on the {{Wiki|Yamuna river}}. {{Wiki|Mathura}} had 2,000 [[monks]] of both major [[Buddhist]] branches, despite {{Wiki|being}} Hindu-dominated. [[Xuanzang]] travelled up the [[river]] to Srughna before crossing eastward to Matipura, where he arrived in 635, having crossed the [[river]] [[Ganges]]. From here, he headed {{Wiki|south}} to Sankasya (Kapitha), said to be where [[Buddha]] descended from [[heaven]], then onward to the northern [[Indian]] [[emperor]] Harsha's grand {{Wiki|capital}} of Kanyakubja (Kanauji). Here, in 636, [[Xuanzang]] encountered 100 [[monasteries]] of 10,000 [[monks]] (both [[Mahayana]] and " [[Hinayana]]"), and was impressed by the king's patronage of both {{Wiki|scholarship}} and [[Buddhism]]. [[Xuanzang]] spent [[time]] in the city studying [[Theravada]] [[scriptures]], before setting off eastward again for [[Ayodhya]] ([[Saketa]]), homeland of the [[Yogacara]] school. [[Xuanzang]] now moved {{Wiki|south}} to Kausambi (Kosam), where he had a copy made from an important local {{Wiki|image}} of the [[Buddha]]. | + | In 634 he went {{Wiki|east}} to [[Jalandhar]] in eastern [[Punjab]], before climbing up to visit predominantly " [[Hinayana]]" [[monasteries]] in the {{Wiki|Kulu}} valley and turning southward again to [[Bairat]] and then {{Wiki|Mathura}}, on the {{Wiki|Yamuna river}}. {{Wiki|Mathura}} had 2,000 [[monks]] of both major [[Buddhist]] branches, despite {{Wiki|being}} Hindu-dominated. [[Xuanzang]] travelled up the [[river]] to Srughna before crossing eastward to [[Matipura]], where he arrived in 635, having crossed the [[river]] [[Ganges]]. From here, he headed {{Wiki|south}} to [[Sankasya]] ([[Kapitha]]), said to be where [[Buddha]] descended from [[heaven]], then onward to the northern [[Indian]] [[emperor]] [[Harsha's]] grand {{Wiki|capital}} of [[Kanyakubja]] (Kanauji). Here, in 636, [[Xuanzang]] encountered 100 [[monasteries]] of 10,000 [[monks]] (both [[Mahayana]] and " [[Hinayana]]"), and was impressed by the king's {{Wiki|patronage}} of both {{Wiki|scholarship}} and [[Buddhism]]. [[Xuanzang]] spent [[time]] in the city studying [[Theravada]] [[scriptures]], before setting off eastward again for [[Ayodhya]] ([[Saketa]]), homeland of the [[Yogacara]] school. [[Xuanzang]] now moved {{Wiki|south}} to [[Kausambi]] (Kosam), where he had a copy made from an important local {{Wiki|image}} of the [[Buddha]]. |

| − | [[Xuanzang]] now returned northward to [[Sravasti]], travelled through Terai in the southern part of {{Wiki|modern}} [[Nepal]] (here he found deserted [[Buddhist]] [[monasteries]]) and thence to [[Kapilavastu]], his last stop before [[Lumbini]], the birthplace of [[Buddha]]. Reaching [[Lumbini]], he would have seen a pillar near the old [[Ashoka tree]] that [[Buddha]] is said to have been born under. This was from the reign of [[emperor]] [[Ashoka]], and records that he worshipped at the spot. The pillar was rediscovered by A. Fuhrer in 1895. | + | [[Xuanzang]] now returned northward to [[Sravasti]], travelled through [[Terai]] in the southern part of {{Wiki|modern}} [[Nepal]] (here he found deserted [[Buddhist]] [[monasteries]]) and thence to [[Kapilavastu]], his last stop before [[Lumbini]], the birthplace of [[Buddha]]. Reaching [[Lumbini]], he would have seen a pillar near the old [[Ashoka tree]] that [[Buddha]] is said to have been born under. This was from the reign of [[emperor]] [[Ashoka]], and records that he worshipped at the spot. The pillar was rediscovered by A. Fuhrer in 1895. |

In 637, [[Xuanzang]] set out from [[Lumbini]] to [[Kusinagara]], the site of [[Buddha's]] [[death]], before heading {{Wiki|southwest}} to the [[deer park]] at [[Sarnath]] where [[Buddha]] gave his first {{Wiki|sermon}}, and where [[Xuanzang]] found 1,500 resident [[monks]]. Travelling eastward, at first via [[Varanasi]], [[Xuanzang]] reached [[Vaisali]], [[Pataliputra]] ( [[Patna]]) and [[Bodh Gaya]]. He was then accompanied by local [[monks]] to [[Nalanda]], the great {{Wiki|ancient}} {{Wiki|university}} of [[India]], where he spent at least the next two years. He was in the company of several thousand scholar-monks, whom he praised. [[Xuanzang]] studied [[logic]], [[grammar]], [[Sanskrit]], and the [[Yogacara]] school of [[Buddhism]] during his [[time]] at [[Nalanda]]. | In 637, [[Xuanzang]] set out from [[Lumbini]] to [[Kusinagara]], the site of [[Buddha's]] [[death]], before heading {{Wiki|southwest}} to the [[deer park]] at [[Sarnath]] where [[Buddha]] gave his first {{Wiki|sermon}}, and where [[Xuanzang]] found 1,500 resident [[monks]]. Travelling eastward, at first via [[Varanasi]], [[Xuanzang]] reached [[Vaisali]], [[Pataliputra]] ( [[Patna]]) and [[Bodh Gaya]]. He was then accompanied by local [[monks]] to [[Nalanda]], the great {{Wiki|ancient}} {{Wiki|university}} of [[India]], where he spent at least the next two years. He was in the company of several thousand scholar-monks, whom he praised. [[Xuanzang]] studied [[logic]], [[grammar]], [[Sanskrit]], and the [[Yogacara]] school of [[Buddhism]] during his [[time]] at [[Nalanda]]. | ||

[[File:Xuanzang478.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang478.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Xuanzang]] turned southward and travelled to Andhradesa to visit the famous [[Viharas]] at {{Wiki|Amaravati}} and Nagarjunakonda. He stayed at {{Wiki|Amaravati}} and studied 'Abhidhammapitakam'. He observed that there were many [[Viharas]] at {{Wiki|Amaravati}} and some of them were deserted. He later proceeded to Kanchi, the imperial {{Wiki|capital}} of Pallavas and a strong centre of [[Buddhism]]. | + | [[Xuanzang]] turned southward and travelled to [[Andhradesa]] to visit the famous [[Viharas]] at {{Wiki|Amaravati}} and [[Nagarjunakonda]]. He stayed at {{Wiki|Amaravati}} and studied '[[Abhidhammapitakam]]'. He observed that there were many [[Viharas]] at {{Wiki|Amaravati}} and some of them were deserted. He later proceeded to [[Kanchi]], the {{Wiki|imperial}} {{Wiki|capital}} of [[Pallavas]] and a strong centre of [[Buddhism]]. |

His [[influence]] on [[Chinese Buddhism]] | His [[influence]] on [[Chinese Buddhism]] | ||

| − | During his travels he studied with many famous [[Buddhist masters]], especially at the famous center of [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|learning}} at [[Nālanda]] {{Wiki|University}}. When he returned, he brought with him some 657 [[Sanskrit]] texts. With the emperor's support, he set up a large translation bureau in Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), drawing students and collaborators from all over {{Wiki|East Asia}}. He is credited with the translation of some 1,330 fascicles of [[scriptures]] into {{Wiki|Chinese}}. His strongest personal [[interest]] in [[Buddhism]] was in the field of [[Yogācāra]] ([[瑜伽行派]]) or [[Consciousness-only]] ([[唯識]]). | + | During his travels he studied with many famous [[Buddhist masters]], especially at the famous center of [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|learning}} at [[Nālanda]] {{Wiki|University}}. When he returned, he brought with him some 657 [[Sanskrit]] texts. With the [[emperor's]] support, he set up a large translation bureau in [[Chang'an]] (present-day {{Wiki|Xi'an}}), drawing students and collaborators from all over {{Wiki|East Asia}}. He is credited with the translation of some 1,330 fascicles of [[scriptures]] into {{Wiki|Chinese}}. His strongest personal [[interest]] in [[Buddhism]] was in the field of [[Yogācāra]] ([[瑜伽行派]]) or [[Consciousness-only]] ([[唯識]]). |

| − | The force of his own study, translation and commentary of the texts of these [[traditions]] initiated the development of the Faxiang school (法相宗) in {{Wiki|East Asia}}. Although the school itself did not thrive for a long [[time]], its theories regarding [[perception]], [[consciousness]], [[karma]], [[rebirth]], etc. found their way into the [[doctrines]] of other more successful schools. [[Xuanzang's]] closest and most eminent student was {{Wiki|Kuiji}} ([[Wikipedia:Kuiji|窺基]]) who became [[recognized]] as the first [[patriarch]] of the Faxiang school. Hsuan Tsang's [[logic]], as described by {{Wiki|Kuiji}}, was often misunderstood by [[scholars]] of [[Chinese Buddhism]] because they lack the necessary background in {{Wiki|Indian logic}}. | + | The force of his [[own]] study, translation and commentary of the texts of these [[traditions]] [[initiated]] the [[development]] of the [[Faxiang school]] ([[法相宗]]) in {{Wiki|East Asia}}. Although the school itself did not thrive for a long [[time]], its theories regarding [[perception]], [[consciousness]], [[karma]], [[rebirth]], etc. found their way into the [[doctrines]] of other more successful schools. [[Xuanzang's]] closest and most {{Wiki|eminent}} [[student]] was {{Wiki|Kuiji}} ([[Wikipedia:Kuiji|窺基]]) who became [[recognized]] as the first [[patriarch]] of the [[Faxiang school]]. [[Hsuan Tsang's]] [[logic]], as described by {{Wiki|Kuiji}}, was often misunderstood by [[scholars]] of [[Chinese Buddhism]] because they lack the necessary background in {{Wiki|Indian logic}}. |

[[File:Xuanzang36.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang36.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Xuanzang]] was known for his extensive but careful translations of [[Indian]] [[Buddhist texts]] to {{Wiki|Chinese}}, and subsequent recoveries of lost [[Indian]] [[Buddhist texts]] from translated {{Wiki|Chinese}} copies. He is credited with [[writing]] or compiling the [[Cheng Weishi Lun]] as a commentary on these texts. His translation of the [[Heart Sutra]] became and {{Wiki|remains}} standard.He also founded the short-lived but influential Faxiang school of [[Buddhism]]. Additionally, he was known for recording the events of the reign of the northern [[Indian]] [[emperor]], [[Harsha]]. | + | [[Xuanzang]] was known for his extensive but careful translations of [[Indian]] [[Buddhist texts]] to {{Wiki|Chinese}}, and subsequent recoveries of lost [[Indian]] [[Buddhist texts]] from translated {{Wiki|Chinese}} copies. He is credited with [[writing]] or compiling the [[Cheng Weishi Lun]] as a commentary on these texts. His translation of the [[Heart Sutra]] became and {{Wiki|remains}} standard.He also founded the short-lived but influential [[Faxiang school]] of [[Buddhism]]. Additionally, he was known for recording the events of the reign of the northern [[Indian]] [[emperor]], [[Harsha]]. |

The [[Perfection of Wisdom Sutra]] | The [[Perfection of Wisdom Sutra]] | ||

| − | [[Xuanzang]] returned to [[China]] with three copies of the [[Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra]]. [[Xuanzang]], with a team of [[disciple]] translators, commenced translating the voluminous work in 660 CE, using all three versions to ensure the integrity of the source documentation. [[Xuanzang]] was {{Wiki|being}} encouraged by a number of his [[disciple]] translators to render an abridged version. After a suite of [[dreams]] quickened his decision, [[Xuanzang]] determined to render an unabridged, complete volume, faithful to the original of 600 chapters. | + | [[Xuanzang]] returned to [[China]] with three copies of the [[Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra]]. [[Xuanzang]], with a team of [[disciple]] [[translators]], commenced translating the voluminous work in 660 CE, using all three versions to ensure the [[integrity]] of the source documentation. [[Xuanzang]] was {{Wiki|being}} encouraged by a number of his [[disciple]] [[translators]] to render an abridged version. After a suite of [[dreams]] quickened his [[decision]], [[Xuanzang]] determined to render an unabridged, complete volume, [[faithful]] to the original of 600 chapters. |

His Autobiography and {{Wiki|Biography}} | His Autobiography and {{Wiki|Biography}} | ||

| − | In 646, under the Emperor's request, [[Xuanzang]] completed his [[book]] Journey to the {{Wiki|West}} in the [[Great]] {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} ([[大唐西域記]]), which has become one of the [[primary]] sources for the study of {{Wiki|medieval}} {{Wiki|Central Asia}} and [[India]]. This [[book]] was first translated into {{Wiki|French}} by the Sinologist Stanislas Julien in 1857. | + | In 646, under the [[Emperor's]] request, [[Xuanzang]] completed his [[book]] Journey to the {{Wiki|West}} in the [[Great]] {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} ([[大唐西域記]]), which has become one of the [[primary]] sources for the study of {{Wiki|medieval}} {{Wiki|Central Asia}} and [[India]]. This [[book]] was first translated into {{Wiki|French}} by the {{Wiki|Sinologist}} {{Wiki|Stanislas Julien}} in 1857. |

| − | There was also a {{Wiki|biography}} of [[Xuanzang]] written by the [[monk]] Huili (慧立). Both [[books]] were first translated into {{Wiki|English}} by Samuel Beal, in 1884 and 1911 respectively. An {{Wiki|English}} translation with copious notes by Thomas Watters was edited by T. S. {{Wiki|Rhys Davids}} and S.W. Bushell, and published posthumously in {{Wiki|London}} in 1905. | + | There was also a {{Wiki|biography}} of [[Xuanzang]] written by the [[monk]] [[Huili]] ([[慧立]]). Both [[books]] were first translated into {{Wiki|English}} by [[Samuel Beal]], in 1884 and 1911 respectively. An {{Wiki|English}} translation with copious notes by Thomas Watters was edited by T. S. {{Wiki|Rhys Davids}} and S.W. Bushell, and published posthumously in {{Wiki|London}} in 1905. |

His Legacy | His Legacy | ||

[[File:Xuanzang35.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang35.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Xuanzang's]] journey along the so-called {{Wiki|Silk Road}}s, and the legends that grew up around it, inspired the Ming {{Wiki|novel}} Journey to the {{Wiki|West}}, one of the great classics of {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|literature}}. The [[Xuanzang]] of the {{Wiki|novel}} is the [[reincarnation]] of a [[disciple]] of [[Gautama Buddha]], and is protected on his journey by three {{Wiki|powerful}} [[disciples]]. One of them, the {{Wiki|monkey}}, was a popular favourite and profoundly influenced {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|culture}} and contemporary [[Japanese]] manga and anime, (including the popular [[Dragon]] Ball and Saiyuki series'), and became well known in the {{Wiki|West}} by Arthur Waley's translation and later the {{Wiki|cult}} TV series {{Wiki|Monkey}}. | + | [[Xuanzang's]] journey along the so-called {{Wiki|Silk Road}}s, and the {{Wiki|legends}} that grew up around it, inspired the [[Ming]] {{Wiki|novel}} Journey to the {{Wiki|West}}, one of the great classics of {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|literature}}. The [[Xuanzang]] of the {{Wiki|novel}} is the [[reincarnation]] of a [[disciple]] of [[Gautama Buddha]], and is protected on his journey by three {{Wiki|powerful}} [[disciples]]. One of them, the {{Wiki|monkey}}, was a popular favourite and profoundly influenced {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|culture}} and contemporary [[Japanese]] [[manga]] and anime, ([[including]] the popular [[Dragon]] Ball and [[Saiyuki series]]'), and became well known in the {{Wiki|West}} by Arthur Waley's translation and later the {{Wiki|cult}} TV series {{Wiki|Monkey}}. |

| − | In the Yuan Dynasty, there was also a play by Wu Changling (吳昌齡) about [[Xuanzang]] obtaining [[scriptures]]. | + | In the [[Yuan Dynasty]], there was also a play by [[Wu Changling]] ([[吳昌齡]]) about [[Xuanzang]] obtaining [[scriptures]]. |

[[Relics]] | [[Relics]] | ||

| − | A skull [[relic]] purported to be that of [[Xuanzang]] was held in the [[Temple]] of [[Great Compassion]], Tianjin until 1956 when it was taken to [[Nalanda]] - allegedly by the [[Dalai Lama]] - and presented to [[India]]. The [[relic]] is now in the [[Patna]] museum. The Wenshu [[Monastery]] in Chengdu, {{Wiki|Sichuan}} province also claims to have part of [[Xuanzang's]] skull. | + | A [[skull]] [[relic]] purported to be that of [[Xuanzang]] was held in the [[Temple]] of [[Great Compassion]], Tianjin until 1956 when it was taken to [[Nalanda]] - allegedly by the [[Dalai Lama]] - and presented to [[India]]. The [[relic]] is now in the [[Patna]] museum. The [[Wenshu]] [[Monastery]] in {{Wiki|Chengdu}}, {{Wiki|Sichuan}} province also claims to have part of [[Xuanzang's]] [[skull]]. |

See also | See also | ||

| − | [[Great]] Tang Records on the Western Regions | + | [[Great]] Tang Records on the {{Wiki|Western Regions}} |

Journey to the {{Wiki|West}} | Journey to the {{Wiki|West}} | ||

| − | {{Wiki|Sun}} Wukong | + | {{Wiki|Sun}} [[Wukong]] |

{{Wiki|Silk Road}} [[transmission]] of [[Buddhism]] | {{Wiki|Silk Road}} [[transmission]] of [[Buddhism]] | ||

[[Buddhism in China]] | [[Buddhism in China]] | ||

Sino-Indian relations | Sino-Indian relations | ||

| − | Zhang Qian | + | {{Wiki|Zhang Qian}} |

[[File:Xuanzang21.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang21.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

[[Faxian]] | [[Faxian]] | ||

| − | Genjō-sanzō | + | [[Genjō-sanzō]] |

[[Hyecho]] | [[Hyecho]] | ||

| − | Yi Jing | + | [[Yi Jing]] |

Footnotes | Footnotes | ||

| Line 77: | Line 77: | ||

Wriggins, Sally Hovey. [[Xuanzang]]: A [[Buddhist]] [[Pilgrim]] on the {{Wiki|Silk Road}} . Westview Press, 1996. Revised and updated as The {{Wiki|Silk Road}} Journey With [[Xuanzang]] . Westview Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8133-6599-6. | Wriggins, Sally Hovey. [[Xuanzang]]: A [[Buddhist]] [[Pilgrim]] on the {{Wiki|Silk Road}} . Westview Press, 1996. Revised and updated as The {{Wiki|Silk Road}} Journey With [[Xuanzang]] . Westview Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8133-6599-6. | ||

| − | Watters, Thomas. On Yuan Chwang’s Travels in [[India]] Reprint. Hesperides Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1406713879. | + | Watters, Thomas. On [[Yuan Chwang’s]] Travels in [[India]] Reprint. Hesperides Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1406713879. |

| − | Stanislas Julien. 1857. Memoires sur les contrées occidentales . {{Wiki|Paris}}. | + | {{Wiki|Stanislas Julien}}. 1857. Memoires sur les contrées occidentales . {{Wiki|Paris}}. |

Further reading | Further reading | ||

| − | Beal, Samuel (1884). Si-Yu-Ki: [[Buddhist]] Records of the Western [[World]], by Hiuen Tsiang . 2 vols. Translated by Samuel Beal. {{Wiki|London}}. 1884. Reprint: Delhi. {{Wiki|Oriental}} [[Books]] Reprint Corporation. 1969. | + | Beal, Samuel (1884). [[Si-Yu-Ki]]: [[Buddhist]] Records of the {{Wiki|Western}} [[World]], by [[Hiuen Tsiang]] . 2 vols. Translated by [[Samuel Beal]]. {{Wiki|London}}. 1884. Reprint: {{Wiki|Delhi}}. {{Wiki|Oriental}} [[Books]] Reprint Corporation. 1969. |

| − | Beal, Samuel (1911). The [[Life]] of Hiuen-Tsiang. Translated from the {{Wiki|Chinese}} of {{Wiki|Shaman}} ([[monk]]) Hwui Li by Samuel Beal. {{Wiki|London}}. 1911. Reprint Munshiram Manoharlal, {{Wiki|New Delhi}}. 1973. | + | Beal, Samuel (1911). The [[Life]] of Hiuen-Tsiang. Translated from the {{Wiki|Chinese}} of {{Wiki|Shaman}} ([[monk]]) Hwui Li by [[Samuel Beal]]. {{Wiki|London}}. 1911. Reprint Munshiram Manoharlal, {{Wiki|New Delhi}}. 1973. |

Bernstein, Richard (2001). [[Ultimate]] Journey: Retracing the [[Path]] of an {{Wiki|Ancient}} [[Buddhist Monk]] ([[Xuanzang]]) who crossed {{Wiki|Asia}} in Search of [[Enlightenment]] . Alfred A. Knopf, {{Wiki|New York}}. ISBN 0-375-40009-5 | Bernstein, Richard (2001). [[Ultimate]] Journey: Retracing the [[Path]] of an {{Wiki|Ancient}} [[Buddhist Monk]] ([[Xuanzang]]) who crossed {{Wiki|Asia}} in Search of [[Enlightenment]] . Alfred A. Knopf, {{Wiki|New York}}. ISBN 0-375-40009-5 | ||

| − | Li, Rongxi (translator) (1995). A {{Wiki|Biography}} of the [[Tripiṭaka]] [[Master]] of the [[Great]] Ci’en [[Monastery]] of the [[Great]] {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} . Numata Center for [[Buddhist]] Translation and Research. {{Wiki|Berkeley}}, California. ISBN 1-886439-00-1 | + | Li, Rongxi ([[translator]]) (1995). A {{Wiki|Biography}} of the [[Tripiṭaka]] [[Master]] of the [[Great]] [[Ci’en]] [[Monastery]] of the [[Great]] {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} . Numata [[Center]] for [[Buddhist]] Translation and Research. {{Wiki|Berkeley}}, {{Wiki|California}}. ISBN 1-886439-00-1 |

| − | Li, Rongxi (translator) (1995). The [[Great]] {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} [[Record of the Western Regions]] . Numata Center for [[Buddhist]] Translation and Research. {{Wiki|Berkeley}}, California. ISBN 1-886439-02-8 | + | Li, Rongxi ([[translator]]) (1995). The [[Great]] {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} [[Record of the Western Regions]] . Numata [[Center]] for [[Buddhist]] Translation and Research. {{Wiki|Berkeley}}, {{Wiki|California}}. ISBN 1-886439-02-8 |

| − | Saran, Mishi (2005). Chasing the Monk’s Shadow: A Journey in the Footsteps of [[Xuanzang]] . Penguin/Viking, {{Wiki|New Delhi}}. | + | Saran, Mishi (2005). Chasing the [[Monk’s]] Shadow: A Journey in the Footsteps of [[Xuanzang]] . Penguin/Viking, {{Wiki|New Delhi}}. |

Gordon, Stewart. When {{Wiki|Asia}} was the [[World]]: Traveling {{Wiki|Merchants}}, [[Scholars]], {{Wiki|Warriors}}, and [[Monks]] who created the "Riches of the {{Wiki|East}}" Da Capo Press, Perseus [[Books]], 2008. ISBN 0-306-81556-7. | Gordon, Stewart. When {{Wiki|Asia}} was the [[World]]: Traveling {{Wiki|Merchants}}, [[Scholars]], {{Wiki|Warriors}}, and [[Monks]] who created the "Riches of the {{Wiki|East}}" Da Capo Press, Perseus [[Books]], 2008. ISBN 0-306-81556-7. | ||

{{Wiki|Sun}} Shuyun (2003). Ten Thousand {{Wiki|Miles}} without a Cloud (retracing [[Xuanzang's]] journeys). Harper [[Perennial]]. ISBN 0-00-712974-2 | {{Wiki|Sun}} Shuyun (2003). Ten Thousand {{Wiki|Miles}} without a Cloud (retracing [[Xuanzang's]] journeys). Harper [[Perennial]]. ISBN 0-00-712974-2 | ||

| − | Wriggins, Sally Hovey (2004). The {{Wiki|Silk Road}} Journey with [[Xuanzang]] . Boulder, Colorado: WestviewPress. ISBN 0-8133-6599-6 | + | Wriggins, Sally Hovey (2004). The {{Wiki|Silk Road}} Journey with [[Xuanzang]] . {{Wiki|Boulder, Colorado}}: WestviewPress. ISBN 0-8133-6599-6 |

Waley, Arthur (1952). The {{Wiki|Real}} [[Tripitaka]], and Other Pieces . {{Wiki|London}}: G. Allen and Unwin. | Waley, Arthur (1952). The {{Wiki|Real}} [[Tripitaka]], and Other Pieces . {{Wiki|London}}: G. Allen and Unwin. | ||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

Details of [[Xuanzang's]] [[life]] and works | Details of [[Xuanzang's]] [[life]] and works | ||

| − | {{Wiki|History}} of San Zang A narration of Xuan Zang's journey to [[India]]. | + | {{Wiki|History}} of San [[Zang]] A narration of Xuan Zang's journey to [[India]]. |

[[Xuanzang's]] Journey In the footsteps of [[Xuanzang]] | [[Xuanzang's]] Journey In the footsteps of [[Xuanzang]] | ||

| − | 大慈恩寺三藏法师传 (全文) {{Wiki|Chinese}} text of The [[Life]] of Hiuen-Tsiang , by {{Wiki|Shaman}} ([[monk]]) Hwui Li (Hui Li) (沙门慧立) | + | 大慈恩寺三藏法师传 (全文) {{Wiki|Chinese}} text of The [[Life]] of Hiuen-Tsiang , by {{Wiki|Shaman}} ([[monk]]) Hwui Li ([[Hui]] Li) (沙门慧立) |

The [[Prajñāpāramitā]] [[Heart Sūtra]] Translated from the {{Wiki|Chinese}} version of [[Xuanzang]]. | The [[Prajñāpāramitā]] [[Heart Sūtra]] Translated from the {{Wiki|Chinese}} version of [[Xuanzang]]. | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

Latest revision as of 22:37, 23 November 2020

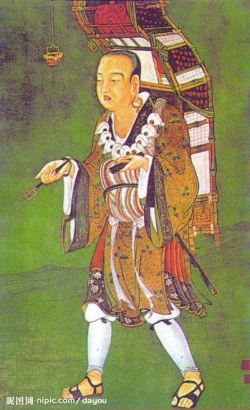

Xuanzang (pronounced Shwan-dzang ) was a famous Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator that brought up the interaction between China and India in the early Tang period.

He became famous for his seventeen year overland trip to India and back, which is recorded in detail in his autobiography and a biography.

Nomenclature, orthography and etymology

Xuanzang is also known as Táng-sānzàng (唐三藏) or simply as Táng Sēng (唐僧), or Tang (Dynasty) Monk in Mandarin; in Cantonese as Tong Sam Jong and in Vietnamese as Đường Tam Tạng . Less common romanizations of Xuanzang include Hhuen Kwan, Hiouen Thsang, Hiuen Tsiang, Hsien-tsang, Hsyan-tsang, Hsuan Chwang, Hsuan Tsiang, Hwen Thsang, Xuan Cang, Xuan Zang, Shuen Shang, Yuan Chang, Yuan Chwang, and Yuen Chwang . Hsüan, Hüan, Huan and Chuang are also found. In Korean, he is known as Hyeon Jang . In Japanese, he is known as Genjō , or Genjō-sanzō (Xuanzang-sanzang). In Vietnamese, he is known as Đường Tăng (Tang Buddhist monk), Đường Tam Tạng ("Tang Tripitaka" monk), Huyền Trang (the Han-Vietnamese name of Xuanzang )

Sānzàng (三藏) is the Chinese term for the Tripitaka scriptures, and in some English-language fiction he is addressed with this title.

Early life

Xuanzang was born near Luoyang, Henan in 602? as Chén Huī or Chén Yī (陳 褘) and died 5th Feb. 664 in Yu Hua Gong (玉華宮). Xuanzang, whose lay name was Chen Hui, was born into a family noted for its erudition for generations. He was the youngest of four children. His great-grandfather was an official serving as a prefect, his grandfather was appointed as professor in the Imperial College at the capital. His father was a conservative Confucianist who gave up office and withdrew into seclusion to escape the political turmoil that gripped China at that time. According to traditional biographies, Xuanzang displayed a superb intelligence and earnestness, amazing his father by his careful observance of the Confucian rituals at the age of eight. Along with his brothers and sister, he received an early education from his father, who instructed him in classical works on filial piety and several other canonical treatises of orthodox Confucianism.

Although his household in Chenhe Village of Goushi Town (緱氏 gou1), Luo Prefecture (洛州), Henan, was essentially Confucian, at a young age Xuanzang expressed interest in becoming a Buddhist monk as one of his elder brothers had done. After the death of his father in 611, he lived with his older brother Chensu (later known as Changjie) for five years at Jingtu Monastery (淨土寺) in Luoyang, supported by the Sui Dynasty state. During this time he studied both Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism, preferring the latter.

In 618, the Sui Dynasty collapsed and Xuanzang and his brother fled to Chang'an, which had been proclaimed as the capital of the Tang state, and thence southward to Chengdu, Sichuan. Here the two brothers spent two or three years in further study in the monastery of Kong Hui, including the Abhidharmakosa-sastra (Abhidharma Storehouse Treatise). When Xuanzang requested to take Buddhist orders at the age of thirteen, the abbot Zheng Shanguo made an exception in his case because of his precocious knowledge.

Xuanzang was fully ordained as a monk in 622, at the age of twenty. The myriad contradictions and discrepancies in the texts at that time prompted Xuanzang to decide to go to India and study in the cradle of Buddhism. He subsequently left his brother and returned to Chang'an to study foreign languages and to continue his study of Buddhism. He began his mastery of Sanskrit in 626, and probably also studied Tocharian. During this time Xuanzang also became interested in the metaphysical Yogacara school of Buddhism.

Pilgrimage

In 629, Xuanzang reportedly had a dream that convinced him to journey to India. The Tang Dynasty and Eastern Türk Göktürks were waging war at the time; therefore Emperor Tang Taizong prohibited foreign travel. Xuanzang persuaded some Buddhist guards at the gates of Yumen and slipped out of the empire via Liangzhou ( Gansu), and Qinghai province. He subsequently travelled across the Gobi Desert to Kumul (Hami), thence following the Tian Shan westward, arriving in Turfan in 630. Here he met the king of Turfan, a Buddhist who equipped him further for his travels with letters of introduction and valuables to serve as funds.

Moving further westward, Xuanzang escaped robbers to reach Yanqi, then toured the Theravada monasteries of Kucha. Further west he passed Aksu before turning northwest to cross the Tian Shan's Bedal Pass into modern Kyrgyzstan. He skirted Issyk Kul before visiting Tokmak on its northwest, and met the great Khan of the Western Türk, whose relationship to the Tang emperor was friendly at the time. After a feast, Xuanzang continued west then southwest to Tashkent (Chach/Che-Shih), capital of modern day Uzbekistan. From here, he crossed the desert further west to Samarkand. In Samarkand, which was under Persian influence, the party came across some abandoned Buddhist temples and Xuanzang impressed the local king with his preaching. Setting out again to the south, Xuanzang crossed a spur of the Pamirs and passed through the famous Iron Gates. Continuing southward, he reached the Amu Darya and Termez, where he encountered a community of more than a thousand Buddhist monks.

Further east he passed through Kunduz, where he stayed for some time to witness the funeral rites of Prince Tardu, who had been poisoned. Here he met the monk Dharmasimha, and on the advice of the late Tardu made the trip westward to Balkh (modern day Afghanistan), to see the Buddhist sites and relics, especially the Nava Vihara, or Nawbahar, which he described as the westernmost monastic institution in the world. Here Xuanzang also found over 3,000 Theravada monks, including Prajnakara, a monk with whom Xuanzang studied Theravada scriptures. He acquired the important [[[Mahāvibhāṣa]]] text here, which he later translated into Chinese. Prajnakara then accompanied the party southward to Bamyan, where Xuanzang met the king and saw tens of Theravada monasteries, in addition to the two large Bamyan Buddhas carved out of the rockface. The party then resumed their travel eastward, crossing the Shibar pass and descending to the regional capital of Kapisi (about 60 km north of modern Kabul), which sported over 100 monasteries and 6,000 monks, mostly Mahayana. This was part of the fabled old land of Gandhara. Xuanzang took part in a religious debate here, and demonstrated his knowledge of many Buddhist sects. Here he also met the first Jains and Hindus of his journey. He pushed on to Jalalabad and Laghman, where he considered himself to have reached India. The year was 630.

South Asia

Xuanzang left Jalalabad, which had few Buddhist monks, but many stupas and monasteries. He passed through Hunza and the Khyber Pass to the east, reaching the former capital of Gandhara, on the other side. Peshawar was nothing compared to its former glory, and Buddhism was declining in the region. Xuanzang visited a number of stupas around Peshawar, notably the Kanishka Stupa. This stupa was built just southeast of Peshawar, by a former king of the city. In 1908 it was rediscovered by D.B. Spooner with the help of Xuanzang's account.

Xuanzang left Peshawar and travelled northeast to the Swat Valley. Reaching Udyana, he found 1,400 old monasteries, that had previously supported 18,000 monks. The remnant monks were of the Mahayana school. Xuanzang continued northward and into the Buner Valley, before doubling back via Shabaz Gharni to cross the Indus river at Hund. Thereafter he headed to Taxila, a Mahayana Buddhist kingdom that was a vassal of Kashmir, which is precisely where he headed next. Here he found 5,000 more Buddhist monks in 100 monasteries. Here he met a talented Mahayana monk and spent his next two years (631-633) studying Mahayana alongside other schools of Buddhism. During this time, Xuanzang writes about the Fourth Buddhist council that took place nearby, ca. 100 AD, under the order of King Kanishka of Kushana.

In 633, Xuanzang left Kashmir and journeyed south to Chinabhukti (thought to be modern Firozpur), where he studied for a year with the monk-prince Vinitaprabha.

In 634 he went east to Jalandhar in eastern Punjab, before climbing up to visit predominantly " Hinayana" monasteries in the Kulu valley and turning southward again to Bairat and then Mathura, on the Yamuna river. Mathura had 2,000 monks of both major Buddhist branches, despite being Hindu-dominated. Xuanzang travelled up the river to Srughna before crossing eastward to Matipura, where he arrived in 635, having crossed the river Ganges. From here, he headed south to Sankasya (Kapitha), said to be where Buddha descended from heaven, then onward to the northern Indian emperor Harsha's grand capital of Kanyakubja (Kanauji). Here, in 636, Xuanzang encountered 100 monasteries of 10,000 monks (both Mahayana and " Hinayana"), and was impressed by the king's patronage of both scholarship and Buddhism. Xuanzang spent time in the city studying Theravada scriptures, before setting off eastward again for Ayodhya (Saketa), homeland of the Yogacara school. Xuanzang now moved south to Kausambi (Kosam), where he had a copy made from an important local image of the Buddha.

Xuanzang now returned northward to Sravasti, travelled through Terai in the southern part of modern Nepal (here he found deserted Buddhist monasteries) and thence to Kapilavastu, his last stop before Lumbini, the birthplace of Buddha. Reaching Lumbini, he would have seen a pillar near the old Ashoka tree that Buddha is said to have been born under. This was from the reign of emperor Ashoka, and records that he worshipped at the spot. The pillar was rediscovered by A. Fuhrer in 1895.

In 637, Xuanzang set out from Lumbini to Kusinagara, the site of Buddha's death, before heading southwest to the deer park at Sarnath where Buddha gave his first sermon, and where Xuanzang found 1,500 resident monks. Travelling eastward, at first via Varanasi, Xuanzang reached Vaisali, Pataliputra ( Patna) and Bodh Gaya. He was then accompanied by local monks to Nalanda, the great ancient university of India, where he spent at least the next two years. He was in the company of several thousand scholar-monks, whom he praised. Xuanzang studied logic, grammar, Sanskrit, and the Yogacara school of Buddhism during his time at Nalanda.

Xuanzang turned southward and travelled to Andhradesa to visit the famous Viharas at Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda. He stayed at Amaravati and studied 'Abhidhammapitakam'. He observed that there were many Viharas at Amaravati and some of them were deserted. He later proceeded to Kanchi, the imperial capital of Pallavas and a strong centre of Buddhism.

His influence on Chinese Buddhism

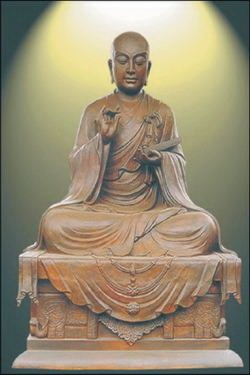

During his travels he studied with many famous Buddhist masters, especially at the famous center of Buddhist learning at Nālanda University. When he returned, he brought with him some 657 Sanskrit texts. With the emperor's support, he set up a large translation bureau in Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), drawing students and collaborators from all over East Asia. He is credited with the translation of some 1,330 fascicles of scriptures into Chinese. His strongest personal interest in Buddhism was in the field of Yogācāra (瑜伽行派) or Consciousness-only (唯識).

The force of his own study, translation and commentary of the texts of these traditions initiated the development of the Faxiang school (法相宗) in East Asia. Although the school itself did not thrive for a long time, its theories regarding perception, consciousness, karma, rebirth, etc. found their way into the doctrines of other more successful schools. Xuanzang's closest and most eminent student was Kuiji (窺基) who became recognized as the first patriarch of the Faxiang school. Hsuan Tsang's logic, as described by Kuiji, was often misunderstood by scholars of Chinese Buddhism because they lack the necessary background in Indian logic.

Xuanzang was known for his extensive but careful translations of Indian Buddhist texts to Chinese, and subsequent recoveries of lost Indian Buddhist texts from translated Chinese copies. He is credited with writing or compiling the Cheng Weishi Lun as a commentary on these texts. His translation of the Heart Sutra became and remains standard.He also founded the short-lived but influential Faxiang school of Buddhism. Additionally, he was known for recording the events of the reign of the northern Indian emperor, Harsha.

The Perfection of Wisdom Sutra

Xuanzang returned to China with three copies of the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra. Xuanzang, with a team of disciple translators, commenced translating the voluminous work in 660 CE, using all three versions to ensure the integrity of the source documentation. Xuanzang was being encouraged by a number of his disciple translators to render an abridged version. After a suite of dreams quickened his decision, Xuanzang determined to render an unabridged, complete volume, faithful to the original of 600 chapters.

His Autobiography and Biography

In 646, under the Emperor's request, Xuanzang completed his book Journey to the West in the Great Tang Dynasty (大唐西域記), which has become one of the primary sources for the study of medieval Central Asia and India. This book was first translated into French by the Sinologist Stanislas Julien in 1857.

There was also a biography of Xuanzang written by the monk Huili (慧立). Both books were first translated into English by Samuel Beal, in 1884 and 1911 respectively. An English translation with copious notes by Thomas Watters was edited by T. S. Rhys Davids and S.W. Bushell, and published posthumously in London in 1905.

His Legacy

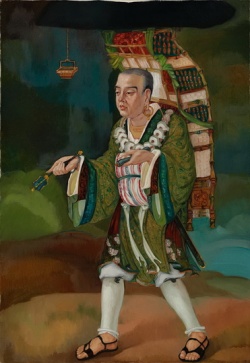

Xuanzang's journey along the so-called Silk Roads, and the legends that grew up around it, inspired the Ming novel Journey to the West, one of the great classics of Chinese literature. The Xuanzang of the novel is the reincarnation of a disciple of Gautama Buddha, and is protected on his journey by three powerful disciples. One of them, the monkey, was a popular favourite and profoundly influenced Chinese culture and contemporary Japanese manga and anime, (including the popular Dragon Ball and Saiyuki series'), and became well known in the West by Arthur Waley's translation and later the cult TV series Monkey.

In the Yuan Dynasty, there was also a play by Wu Changling (吳昌齡) about Xuanzang obtaining scriptures.

Relics

A skull relic purported to be that of Xuanzang was held in the Temple of Great Compassion, Tianjin until 1956 when it was taken to Nalanda - allegedly by the Dalai Lama - and presented to India. The relic is now in the Patna museum. The Wenshu Monastery in Chengdu, Sichuan province also claims to have part of Xuanzang's skull.

See also

Great Tang Records on the Western Regions

Journey to the West

Sun Wukong

Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

Buddhism in China

Sino-Indian relations

Zhang Qian

Faxian

Genjō-sanzō

Hyecho

Yi Jing

Footnotes

References

Wriggins, Sally Hovey. Xuanzang: A Buddhist Pilgrim on the Silk Road . Westview Press, 1996. Revised and updated as The Silk Road Journey With Xuanzang . Westview Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8133-6599-6.

Watters, Thomas. On Yuan Chwang’s Travels in India Reprint. Hesperides Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1406713879.

Stanislas Julien. 1857. Memoires sur les contrées occidentales . Paris.

Further reading

Beal, Samuel (1884). Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang . 2 vols. Translated by Samuel Beal. London. 1884. Reprint: Delhi. Oriental Books Reprint Corporation. 1969.

Beal, Samuel (1911). The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang. Translated from the Chinese of Shaman (monk) Hwui Li by Samuel Beal. London. 1911. Reprint Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi. 1973.

Bernstein, Richard (2001). Ultimate Journey: Retracing the Path of an Ancient Buddhist Monk (Xuanzang) who crossed Asia in Search of Enlightenment . Alfred A. Knopf, New York. ISBN 0-375-40009-5

Li, Rongxi (translator) (1995). A Biography of the Tripiṭaka Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty . Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. Berkeley, California. ISBN 1-886439-00-1

Li, Rongxi (translator) (1995). The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions . Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. Berkeley, California. ISBN 1-886439-02-8

Saran, Mishi (2005). Chasing the Monk’s Shadow: A Journey in the Footsteps of Xuanzang . Penguin/Viking, New Delhi.

Gordon, Stewart. When Asia was the World: Traveling Merchants, Scholars, Warriors, and Monks who created the "Riches of the East" Da Capo Press, Perseus Books, 2008. ISBN 0-306-81556-7.

Sun Shuyun (2003). Ten Thousand Miles without a Cloud (retracing Xuanzang's journeys). Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-712974-2

Wriggins, Sally Hovey (2004). The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang . Boulder, Colorado: WestviewPress. ISBN 0-8133-6599-6

Waley, Arthur (1952). The Real Tripitaka, and Other Pieces . London: G. Allen and Unwin.

External links

Details of Xuanzang's life and works

History of San Zang A narration of Xuan Zang's journey to India.

Xuanzang's Journey In the footsteps of Xuanzang

大慈恩寺三藏法师传 (全文) Chinese text of The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang , by Shaman (monk) Hwui Li (Hui Li) (沙门慧立)

The Prajñāpāramitā Heart Sūtra Translated from the Chinese version of Xuanzang.