Difference between revisions of "Dignaga"

| (11 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

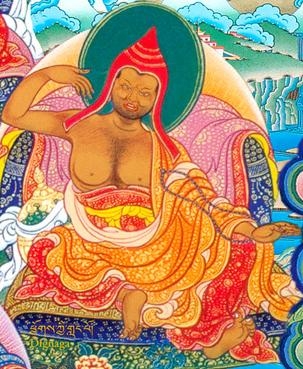

| − | [[File:Dignaga_and_Dharmakirti.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | + | [[Image:Dignaga.JPG|frame|'''Acharya Dignāga''']][[File:Dignaga_and_Dharmakirti.jpg|thumb|250px|]] |

| − | + | ||

| − | [[Dignaga]] | + | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Dignaga]] (Skt. ''[[Dignāga]]''; Tib. {{BigTibetan|[[ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་གླང་པོ་]]}}, [[Wyl.]] ''[[phyogs kyi glang po]]''; Tib. ''[[chok kyi langpo]]'') (circa 6th century AD) was one of the six great commentators (the ‘[[Six Ornaments]]’) on the [[Buddha’s teachings]]. He was one of the four great [[disciples]] of [[Vasubandhu]] who each surpassed their [[teacher]] in a particular field. [[Dignaga]] was more learned than [[Vasubandhu]] in [[pramāṇa]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | His reputation as unequaled in [[debate]] was cemented through his celebrated victory over the [[brahmin]] named [[Sudurjaya]] at [[Nalanda|Nālandā monastery]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Among his [[disciples]] was [[Iśvarasena]], who later became the [[teacher]] of [[Dharmakīrti]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Writings== | ||

| + | |||

| + | His early (extant) works were: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * The [[Abhidharmakośa-marma-pradīpa]] - a condensed summary of [[Vasubandhu]]'s seminal work | ||

| + | * A brief summary of the [[Aṣṭasāhasrika-prajñāpāramitā sūtra]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | His remaining works were all pertaining to [[logic]]: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[Ālambana-parīkṣā]] | ||

| + | * [[Trikāla-parikṣa]] | ||

| + | * [[Hetu-cakra-samarthana]] | ||

| + | * [[Nyāyamukha]] | ||

| + | * [[Compendium of Valid Cognition]] (''[[Pramāṇa-samuccaya]]''), which was a condensation of all these works | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Further Reading== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Nolinking|*Hattori, Masaaki. ''[[Dignāga]], On Perception''. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1968. | ||

| + | *Hayes, Richard P. ''[[Dignāga]] on the Interpretation of Signs''. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer, 1988.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{RigpaWiki}} | ||

| + | {{NewSourceBreak}} | ||

| + | [[Dignāga]] (c.480-540) | ||

[[陳那]] (n.d.) (Skt; Jpn [[Jinna]]) | [[陳那]] (n.d.) (Skt; Jpn [[Jinna]]) | ||

| − | + | A [[south]] [[Indian]] [[monk]] and [[scholar]] who was an indirect [[student]] of [[Vasubandhu]]. He combined aspects of [[Yogācāra]] and [[Sautrāntika]] theories of [[perception]] with his [[own]] innovative [[logical methodology]] ([[pramāṇa]]). | |

| − | + | Based in {{Wiki|Orissa}}, he wrote a number of important works on [[Abhidharma]] and [[pramāṇa]], [[including]] his highly influential [[Pramāṇa-samuccaya]]. This combines many of his earlier [[insights]] into a complete system of [[epistemology]]. | |

| − | + | The work deals with the problems of [[sense-perception]] and its role in [[knowledge]], the reliability of [[knowledge]], and the relationship between [[sensations]], images, [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], and the [[external world]]. | |

| − | + | After [[Dignāga]] the [[lineage]] continued through his pupil [[Īśvarasena]] to the great [[Dharmakīrti]] in the 7th century. | |

| − | + | An [[Indian]] {{Wiki|scholar}} of the [[Consciousness-Only school]] who lived from the fifth through the sixth century. | |

| − | + | Also a {{Wiki|scholar}} of [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|logic}}. Born to a {{Wiki|Brahman}} [[family]] in southern {{Wiki|India}}, he studied both [[Hinayana]] and [[Mahayana]] [[Buddhism]]. He further developed the [[ideas]] of [[Vasubandhu]] and established a branch of the [[Consciousness-Only school]] that regarded the images stored in the [[alaya-consciousness]] as {{Wiki|real}} rather than [[non-substantial]]. | |

| − | + | This [[teaching]] was inherited by [[Asvabhava]], [[Dharmapala]], [[Shilabhadra]], and [[Hsüan-tsang]]. [[Hsüan-tsang]] laid the foundation for the [[Dharma Characteristics]] ([[Fa-hsiang]]) school in {{Wiki|China}}. | |

| + | |||

| + | [[Dignaga]] also contributed to the [[development]] of [[Buddhist logic]], advancing a new [[form]] of {{Wiki|deductive}} {{Wiki|reasoning}}. His works include The [[Treatise on the Objects of Cognition]], The [[Treatise on Systems of Cognition]], and The [[Treatise on the Correct Principles of Logic]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

| − | [http://www.sgilibrary.org/search_dict.php | + | [http://www.sgilibrary.org/search_dict.php?id=455 sgilibrary.org] |

| + | {{NewSourceBreak}} | ||

| + | [[Dignāga]] ({{Wiki|Chinese}}: [[陳那論師/域龍]], [[Sanskrit]]: {{SanskritBig|[[दिग्नाग]]}}, [[Tibetan]]: {{BigTibetan|[[ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་གླང་པོ་]]}}) (c 480-540 CE) was an [[Indian]] [[scholar]] and one of the [[Buddhist]] founders of {{Wiki|Indian logic}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He was born into a [[Brahmin]] [[family]] in [[Simhavakta]] (near {{Wiki|Kanchi Kanchipuram}}), and very little is known of his early years, except that he took as his [[spiritual]] [[preceptor]] [[Nagadatta]] of the {{Wiki|Vatsiputriya}} school, before [[being]] expelled and becoming a [[student]] of [[Vasubandhu]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This branch of [[Buddhist]] [[thought]] defended the [[view]] that there [[exists]] a kind of {{Wiki|real}} [[personality]] {{Wiki|independent}} of the [[elements]] or [[aggregates]] composing it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Among [[Dignaga]]'s works there is {{Wiki|Hetucakra}} (The [[wheel of reason]]), considered his first work on {{Wiki|formal logic}}, advancing a new [[form]] of {{Wiki|deductive}} {{Wiki|reasoning}}. It may be regarded as a bridge between the older [[doctrine]] of {{Wiki|trairūpya}} and [[Dignaga]]'s [[own]] later {{Wiki|theory}} of {{Wiki|vyapti}} which is a {{Wiki|concept}} related to the {{Wiki|Western}} notion of implication. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other works include The Treatise on the [[Objects of Cognition]] ([[Ālambana-parīkṣā]]), The Treatise on [[Systems of Cognition]] ([[Pramāṇa-samuccaya]]), and The Treatise on the [[Correct Principles of Logic]] (*{{Wiki|Nyāya-mukha}}), produced in an [[effort]] to establish what were the valid [[sources of knowledge]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===[[Contribution to Buddhist Logic]]=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | During [[Dignāga]]'s [[time]], the {{Wiki|Nyaya}} school of {{Wiki|Hinduism}} had began to hold [[debates]] using their 5 step approach to making and evaluating arguments with {{Wiki|logic}}. [[Buddhist]] [[debaters]] such as [[Dignāga]] wanted to engage in these [[debates]], and also have a way to [[logically]] evaluate arguments, but a premise such as "all {{Wiki|dogs}} are {{Wiki|mammals}}" proved problematic for his {{Wiki|idealist}} [[Yogacara]] [[philosophy]]. [[Dignāga]] was a [[student]] of [[Vasubandhu]], and therefore believed that "the [[dharmas]] are [[empty]]." | ||

| + | |||

| + | In other words, there are not [[universal]] qualities such as "dog-ness" or "mammal-ness." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Such universals would have to be [[unchanging]], and since all things are [[subject]] to change and are lacking in [[essential]] [[essence]] according to his school of [[philosophy]], [[Dignāga]] attempted to find a way to engage in argument within the {{Wiki|Nyaya}} {{Wiki|structure}} without positing through the arguments that there is an [[essential]] "dog-ness," or what have you. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In [[order]] to do this he employed what is referred to in formal [[logic]] in the {{Wiki|West}} as contraposition, or in [[sanskrit]], {{Wiki|Apoha}}, where one switches the terms and swaps them for their term compliment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Therefore the example premise above, "all {{Wiki|dogs}} are {{Wiki|mammals}}" becomes "all non-mammals are non-dogs." These two statements are [[logically]] {{Wiki|equivalent}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Once this had been done, [[Dignāga]] could make arguments about non-mammals without positing that {{Wiki|mammals}} have an [[essential]] {{Wiki|nature}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | this move gets off the ground towards his goal, {{Wiki|reflection}} shows that making [[universal]] statements about non-mammals still implies that there are {{Wiki|mammals}} who share an [[essential]] {{Wiki|nature}}, and everything else, which lacks this "mammal-ness." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Still, using this method [[Dignāga]] and other [[Buddhist]] [[logicians]] were [[able]] to further their [[logical]] {{Wiki|discourse}} and felt more comfortable engaging in {{Wiki|Nyaya}} structured [[debates]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{W} | ||

[[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | ||

[[Category:Yogacara]] | [[Category:Yogacara]] | ||

[[Category:Dignaga]] | [[Category:Dignaga]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Historical Masters]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Indian Masters]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Seventeen Nalanda Masters]] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:11, 18 May 2023

Dignaga (Skt. Dignāga; Tib. ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་གླང་པོ་, Wyl. phyogs kyi glang po; Tib. chok kyi langpo) (circa 6th century AD) was one of the six great commentators (the ‘Six Ornaments’) on the Buddha’s teachings. He was one of the four great disciples of Vasubandhu who each surpassed their teacher in a particular field. Dignaga was more learned than Vasubandhu in pramāṇa.

His reputation as unequaled in debate was cemented through his celebrated victory over the brahmin named Sudurjaya at Nālandā monastery.

Among his disciples was Iśvarasena, who later became the teacher of Dharmakīrti.

Writings

His early (extant) works were:

- The Abhidharmakośa-marma-pradīpa - a condensed summary of Vasubandhu's seminal work

- A brief summary of the Aṣṭasāhasrika-prajñāpāramitā sūtra

His remaining works were all pertaining to logic:

- Ālambana-parīkṣā

- Trikāla-parikṣa

- Hetu-cakra-samarthana

- Nyāyamukha

- Compendium of Valid Cognition (Pramāṇa-samuccaya), which was a condensation of all these works

Further Reading

- Hattori, Masaaki. Dignāga, On Perception. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1968.

- Hayes, Richard P. Dignāga on the Interpretation of Signs. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer, 1988.

Source

Dignāga (c.480-540)

陳那 (n.d.) (Skt; Jpn Jinna)

A south Indian monk and scholar who was an indirect student of Vasubandhu. He combined aspects of Yogācāra and Sautrāntika theories of perception with his own innovative logical methodology (pramāṇa).

Based in Orissa, he wrote a number of important works on Abhidharma and pramāṇa, including his highly influential Pramāṇa-samuccaya. This combines many of his earlier insights into a complete system of epistemology.

The work deals with the problems of sense-perception and its role in knowledge, the reliability of knowledge, and the relationship between sensations, images, concepts, and the external world.

After Dignāga the lineage continued through his pupil Īśvarasena to the great Dharmakīrti in the 7th century.

An Indian scholar of the Consciousness-Only school who lived from the fifth through the sixth century.

Also a scholar of Buddhist logic. Born to a Brahman family in southern India, he studied both Hinayana and Mahayana Buddhism. He further developed the ideas of Vasubandhu and established a branch of the Consciousness-Only school that regarded the images stored in the alaya-consciousness as real rather than non-substantial.

This teaching was inherited by Asvabhava, Dharmapala, Shilabhadra, and Hsüan-tsang. Hsüan-tsang laid the foundation for the Dharma Characteristics (Fa-hsiang) school in China.

Dignaga also contributed to the development of Buddhist logic, advancing a new form of deductive reasoning. His works include The Treatise on the Objects of Cognition, The Treatise on Systems of Cognition, and The Treatise on the Correct Principles of Logic.

Source

Dignāga (Chinese: 陳那論師/域龍, Sanskrit: दिग्नाग, Tibetan: ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་གླང་པོ་) (c 480-540 CE) was an Indian scholar and one of the Buddhist founders of Indian logic.

He was born into a Brahmin family in Simhavakta (near Kanchi Kanchipuram), and very little is known of his early years, except that he took as his spiritual preceptor Nagadatta of the Vatsiputriya school, before being expelled and becoming a student of Vasubandhu.

This branch of Buddhist thought defended the view that there exists a kind of real personality independent of the elements or aggregates composing it.

Among Dignaga's works there is Hetucakra (The wheel of reason), considered his first work on formal logic, advancing a new form of deductive reasoning. It may be regarded as a bridge between the older doctrine of trairūpya and Dignaga's own later theory of vyapti which is a concept related to the Western notion of implication.

Other works include The Treatise on the Objects of Cognition (Ālambana-parīkṣā), The Treatise on Systems of Cognition (Pramāṇa-samuccaya), and The Treatise on the Correct Principles of Logic (*Nyāya-mukha), produced in an effort to establish what were the valid sources of knowledge.

Contribution to Buddhist Logic

During Dignāga's time, the Nyaya school of Hinduism had began to hold debates using their 5 step approach to making and evaluating arguments with logic. Buddhist debaters such as Dignāga wanted to engage in these debates, and also have a way to logically evaluate arguments, but a premise such as "all dogs are mammals" proved problematic for his idealist Yogacara philosophy. Dignāga was a student of Vasubandhu, and therefore believed that "the dharmas are empty."

In other words, there are not universal qualities such as "dog-ness" or "mammal-ness."

Such universals would have to be unchanging, and since all things are subject to change and are lacking in essential essence according to his school of philosophy, Dignāga attempted to find a way to engage in argument within the Nyaya structure without positing through the arguments that there is an essential "dog-ness," or what have you.

In order to do this he employed what is referred to in formal logic in the West as contraposition, or in sanskrit, Apoha, where one switches the terms and swaps them for their term compliment.

Therefore the example premise above, "all dogs are mammals" becomes "all non-mammals are non-dogs." These two statements are logically equivalent.

Once this had been done, Dignāga could make arguments about non-mammals without positing that mammals have an essential nature.

this move gets off the ground towards his goal, reflection shows that making universal statements about non-mammals still implies that there are mammals who share an essential nature, and everything else, which lacks this "mammal-ness."

Still, using this method Dignāga and other Buddhist logicians were able to further their logical discourse and felt more comfortable engaging in Nyaya structured debates.

{{W}