Difference between revisions of "Lubsan Sandan Tsydenov"

m (Text replacement - "times" to "times") |

m (1 revision: Robo text replace 30 sept) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 18:01, 30 September 2013

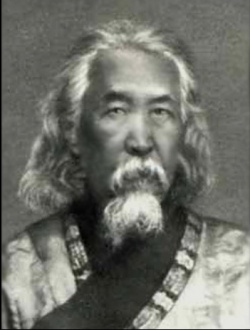

Lubsan Sandan Tsydenov (1850-1922) was a lama from the Kizhinga (Kudun) Datsan in southern Transbaikalia. He was known among his countrymen as a Buddhist scholar, writer and poet but, more importantly, as a great ascetic for his two-decade long practice of austerities in a secluded spot in the Kudun Valley. As a result he acquired great spiritual authority among Buryats who saw him as a saintly Buddha-like creature. His religious name was Sugada, being one of Shakyamuni Buddha’s nicknames, which means in Sanskrit “The happily gone (to Nirvana)”. Sandan Tsydenov formulated his theocratic doctrine in the early 20th century, under the influence of his Tibetan teachers, the incarnate lamas, Jayag (Jayagsy)-gegen, abbot of one of the datsans in Kumbum, and Agpa-gegen. This doctrine had two principal objects – to establish a lay Buddhist sangha in Buryatia, outside and independent of the traditional monastic community, and to revive with its help some of the old Tantric practices. Such a lay sangha, in Tsydenov’s thinking, would be more efficient in the preservation and further dissemination of the Buddhist teachings in times of trouble.

In February 1919 Tsydenov-Sugada established a Buddhist theocratic state, actually an enclave within the Buryat territory, then under the rule of the white Ataman Semionov, by proclaiming himself Dharmaraja, “the King of the Dharma in the Three Worlds”. This was when the Buryat People’s Duma (Burnatsduma), an organ of self-rule in Buryatia, announced the mobilization of the Buryats and Tungus into the people’s tsagda (army). It was an extremely unpopular measure and a large number of Buryats tried to avoid conscription by turning to the lama-ascetic. The latter is said to have addressed his countrymen with the words: “He who does not want to fight, since fighting is against the Buddha’s teachings, let him come unto me and be subject of my rule”.

This was the beginning of the Balagat theocratic movement which united mainly the Kizhinga Buryats who broke off with the official Buddhist (lamaist) church and were commonly referred to as Balagats. The superior dharmic state, Erheje Balgahan ulas (Righfully Detached State), founded by Tsydenov however lasted for only one week before its ruler was arrested by Semionov, together with his nine ministers. The Dharmaraja was soon released though, having formally agreed to collaborate with the white ataman.

In this way the theocratic movement continued for a while with a strong backing of the Buryat believers. It was finally crushed by the Red Army in the early 1920s when the Soviet rule was established in Transbaikalia. Tsydenov was arrested by the Cheka, the notorious Bolshevik political police, in the Irkutsk Province in 1922, put in jail and deported to Novonikolaevsk (today’s Novosibirsk) where he died in a hospital on 16 May 1922.

Tsydenov’s project was certainly a bold undertaking, but practically it had no chance of survival under the tough and uncompromising Soviet regime. His was an idealistic attempt to create a non-violent form of government on the lofty Dharma principles, such as never existed before, a kind of a mystical Buddhist “Pure Land” that would have no military force, or army, so that its subjects would not engage in killing. Politics was seen by him as inseparable from religion and religious ethics, yet Tsydenov’s theocracy was something very different from the traditional Mongolian and Tibetan types of theocracy. Tsydenov adopted a constitution which established the Great Suglan, an assembly of people’s deputies who were to elect, by secret voting, the president, vice-president and ministers of his theocratic government. Still the supreme political and religious authority was to remain in the hands of the Dharmaraja. As the Buryat scholar N.V. Tsyrempilov points out, by making this provision Tsydenov clearly followed European democratic standards. Thus his project was ultimately a “kind of fusion of the Buddhist theocratic model with Europeans models of state”.

See also

- Samdan Tsydenov And His Buddhist Theocratic Project In Siberia by Nikolay Tsyrempilov

- Dreams of a Pan-Mongolian state by Alexandre Andreyev