Difference between revisions of "Ganges"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| The Ganges (''Gaṅgā'') is the longest river in India and flows through the Middle Land, that part of India where the Buddha lived. It wa...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

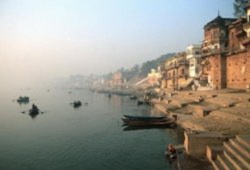

[[File:Ganges.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Ganges.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The Ganges (''Gaṅgā'') is the longest river in India and flows through the Middle Land, that part of India where | + | The Ganges (''Gaṅgā'') is the longest river in [[India]] and flows through the Middle Land, that part of [[India]] where [[The Buddha]] lived. It was also sometimes called Bhāgīrathī (J.V,255). The river’s great size and [[Beauty]] and its ability to both nourish crops and to sweep away villages when in flood meant that it was looked upon with a mixture of reverence and awe. A character in the [[Jātaka]] says: ‘I revere the Ganges whose waters flow and spread.’ (J.V,93). The Milky Way was called the Celestial Ganges (''Ākāsagaṅgā'', Ja.II,65). Hindus believed, as they still do, that the river’s waters wash away the effects of any [[Evil]] they have done, a belief which [[The Buddha]] criticized (M.I,39). The commentaries give a completely fantastic description of the river’s source and first reaches, saying that it starts from Lake Anotatta, rises up into the air and then passes through several rock tunnels before flowing into [[India]]. The Tipiṭaka says nothing about the source of the Ganges other than that it starts somewhere in the [[Himalayas]]. The Jatākas often say that when the [[Bodhisattva]] was an [[Ascetic]] in his former lives, he went into the [[Himalayas]] and ‘made a hermitage near a bend in the Ganges’ (e.g. Ja.II,145; II,258). The upper reaches of the Ganges were called Uddhagaṅgā (Ja.II,283), the Yamunā joins it at Payāga (modern Allahabad, Ja.II,151) and the river eventually flows into the sea (A.IV,199). |

| − | The Buddha often used the Ganges as a simile or metaphor in his teachings (e.g. M.I,225; S.II,184; IV,298). When he wanted to give the idea of an incalculable amount of something he would say that it was as numerous as the grains of sand in the Ganges (S.IV,376), a simile later often used in Mahāyāna literature. When he wanted to emphasize the effectiveness of his teachings for attaining Nirvāṇa he used the inevitable, unstoppable eastward movement of the Ganges to illustrate this idea. He said: ‘Just as the Ganges flows, slides, tends towards the east, so too, one who cultivates and makes much of the | + | [[The Buddha]] often used the Ganges as a simile or metaphor in his teachings (e.g. M.I,225; S.II,184; IV,298). When he wanted to give the idea of an incalculable amount of something he would say that it was as numerous as the grains of sand in the Ganges (S.IV,376), a simile later often used in [[Mahāyāna]] literature. When he wanted to emphasize the effectiveness of his teachings for attaining [[Nirvāṇa]] he used the inevitable, unstoppable eastward movement of the Ganges to illustrate this idea. He said: ‘Just as the Ganges flows, slides, tends towards the east, so too, one who cultivates and makes much of the [[NOBLE EIGHTFOLD PATH]] flows, slides tends towards [[Nirvāṇa]].’ (S.V,40). |

| − | When | + | When [[The Buddha]] left Pāṭaliputta (now Patna) during his last journey, he had to cross the Ganges in order to get to [[Vesāli]]. Today the river at this point is nearly a kilometer wide and it was probably just as wide in ancient times too. The townspeople who had come to bid him goodbye walked up and down along the river bank looking for a ferry or a boat to use to cross the river. Some even began binding reeds together in an attempt to make rafts. Then, according to the Mahāparinibbāna [[Sutta]], ‘as quickly as a strong man might stretch out his arm and draw it back again, [[The Buddha]] and his [[Monks]] vanished from this bank and reappeared on the other bank of the Ganges’ (D.II,89). |

| + | |||

| + | See also: Ganga | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://www.buddhisma2z.com/content.php?id=147 www.buddhisma2z.com] | [http://www.buddhisma2z.com/content.php?id=147 www.buddhisma2z.com] | ||

Revision as of 05:32, 10 May 2013

The Ganges (Gaṅgā) is the longest river in India and flows through the Middle Land, that part of India where The Buddha lived. It was also sometimes called Bhāgīrathī (J.V,255). The river’s great size and Beauty and its ability to both nourish crops and to sweep away villages when in flood meant that it was looked upon with a mixture of reverence and awe. A character in the Jātaka says: ‘I revere the Ganges whose waters flow and spread.’ (J.V,93). The Milky Way was called the Celestial Ganges (Ākāsagaṅgā, Ja.II,65). Hindus believed, as they still do, that the river’s waters wash away the effects of any Evil they have done, a belief which The Buddha criticized (M.I,39). The commentaries give a completely fantastic description of the river’s source and first reaches, saying that it starts from Lake Anotatta, rises up into the air and then passes through several rock tunnels before flowing into India. The Tipiṭaka says nothing about the source of the Ganges other than that it starts somewhere in the Himalayas. The Jatākas often say that when the Bodhisattva was an Ascetic in his former lives, he went into the Himalayas and ‘made a hermitage near a bend in the Ganges’ (e.g. Ja.II,145; II,258). The upper reaches of the Ganges were called Uddhagaṅgā (Ja.II,283), the Yamunā joins it at Payāga (modern Allahabad, Ja.II,151) and the river eventually flows into the sea (A.IV,199). The Buddha often used the Ganges as a simile or metaphor in his teachings (e.g. M.I,225; S.II,184; IV,298). When he wanted to give the idea of an incalculable amount of something he would say that it was as numerous as the grains of sand in the Ganges (S.IV,376), a simile later often used in Mahāyāna literature. When he wanted to emphasize the effectiveness of his teachings for attaining Nirvāṇa he used the inevitable, unstoppable eastward movement of the Ganges to illustrate this idea. He said: ‘Just as the Ganges flows, slides, tends towards the east, so too, one who cultivates and makes much of the NOBLE EIGHTFOLD PATH flows, slides tends towards Nirvāṇa.’ (S.V,40). When The Buddha left Pāṭaliputta (now Patna) during his last journey, he had to cross the Ganges in order to get to Vesāli. Today the river at this point is nearly a kilometer wide and it was probably just as wide in ancient times too. The townspeople who had come to bid him goodbye walked up and down along the river bank looking for a ferry or a boat to use to cross the river. Some even began binding reeds together in an attempt to make rafts. Then, according to the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, ‘as quickly as a strong man might stretch out his arm and draw it back again, The Buddha and his Monks vanished from this bank and reappeared on the other bank of the Ganges’ (D.II,89).

See also: Ganga