Difference between revisions of "Wisdom of Buddha: The Samdhinirmocana Sutra"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{DisplayImages|3498|1681|1885|2600|2225|945|1627|182|2111|2744|777|1460|1355|79|231|158|894|1205|1317|2122|2675|2217|1739|3238|2238|3644|1501|1162|1377|582|1403|2114|2580|2787|2949|254|695|872|36|3334|1637|2654|862|601|149|2384|696|2362|2222|2216|2331|2759|1076|438|1106|1604|199|2747|2194|3019|2531|2799|2719|31|2182|2589|1788|2500|2964|2625|1374|1904|700|1217|1430|210|1993|2008|645|1829|1737|1492|140|1249|421|2482|204|2688|2220|2939|1954|524|23|2547|1068|397|288|2898|1547|2979|1243|3120|1443|722|1764|2483|3082|3247|1356|927|3214|971|1304|2359|3032|774|1828|2000|495|690|2305|564|3291|1569|253|1198|756|2074|864|1729|1146|3017|2291|2278|3450|2195|361|3331|472|388|3638|867|2052|544|1424|1946|295|1428|2108|2391|1617|2604|370|522|926|545|261|1668|1204|321|1625|1467|1407|684|2200|1738|2112|2755|836|2368|3303|1839|2342|181|252|27 | + | {{DisplayImages|3498|1681|1885|2600|2225|945|1627|182|2111|2744|777|1460|1355|79|231|158|894|1205|1317|2122|2675|2217|1739|3238|2238|3644|1501|1162|1377|582|1403|2114|2580|2787|2949|254|695|872|36|3334|1637|2654|862|601|149|2384|696|2362|2222|2216|2331|2759|1076|438|1106|1604|199|2747|2194|3019|2531|2799|2719|31|2182|2589|1788|2500|2964|2625|1374|1904|700|1217|1430|210|1993|2008|645|1829|1737|1492|140|1249|421|2482|204|2688|2220|2939|1954|524|23|2547|1068|397|288|2898|1547|2979|1243|3120|1443|722|1764|2483|3082|3247|1356|927|3214|971|1304|2359|3032|774|1828|2000|495|690|2305|564|3291|1569|253|1198|756|2074|864|1729|1146|3017|2291|2278|3450|2195|361|3331|472|388|3638|867|2052|544|1424|1946|295|1428|2108|2391|1617|2604|370|522|926|545|261|1668|1204|321|1625|1467|1407|684|2200|1738|2112|2755|836|2368|3303|1839|2342|181|252|27}} |

{{Centre|<big>Wisdom of Buddha</big> | {{Centre|<big>Wisdom of Buddha</big> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | <big><big>The Samdhinirmocana Sutra</big></big> <br/> | + | <big><big>The [[Samdhinirmocana Sutra]]</big></big> <br/> |

Translated by | Translated by | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

Revision as of 19:12, 19 March 2014

Wisdom of Buddha

The Samdhinirmocana Sutra

Translated by

John Powers

Preface

Buddhism teaches that life is precious. If we wish to use O our limited time on earth to create a truly meaningful existence, there is no better foundation than the Dharma, the teachings of the Buddha.

The Buddha taught for almost fifty years, and although many of his teachings have been lost over the millennia, thousands of texts have been preserved in Sanskrit, Pali, Tibetan, and Chinese, bringing the wisdom of the Dharma to many lands. Only a few hundred of these texts have been translated into Western languages. Each new translation reveals further aspects of the Buddha's realization, confirming the value of the Dharma and the depth and richness of the teachings. With this publication, the Samdhinirmocana Sūtra becomes available in its entirety in English for the first time.

Considered a Sūtra of definitive meaning, the Samdhinirmocana is among the extraordinary teachings that the Buddha gave to the advanced Bodhisattvas. Its brilliance illuminates ideas and practices of great depth and subtlety. Vast in scope, the Samdhinirmocana is rich in profound meaning that cannot be fully fathomed in one reading. However, patient study, reflection, and rereading will evoke clear insight into the Buddha's awakened vision.

Conveying the deep and subtle meanings of a text such as the Samdhinirmocana into clear, readable English is a demanding task. Buddhist terminology and perspectives are still unfamiliar to the West, and the vocabulary available cannot always convey the ideas being expressed. In the eighth and ninth centuries, when the Dharma was being transmitted to Tibet, Indian p a r k a s and Tibetan lotsāwas worked together to establish uniform standards of translation. As similar efforts are carried out in the West, the challenge of communicating the heart of the Dharma teachings will become easier and the results more accurate. I hope that the present translation will inspire efforts in this direction.

For over twenty years Dharma Publishing has been dedicated to producing Buddhist books and art of the highest quality. Although a work such as this has a very limited audience and is quite difficult to produce, I am confident that the immeasurable virtue of the wisdom that the text contains makes it infinitely worth the effort.

I would like to thank the translator, John Powers, for his careful work. My thanks go as well to the Dharma Publishing editors and production staff, especially Sylvia Gretchen, who worked closely with Dr. Powers to prepare the translation for publication. There is no doubt that the meritorious action of making this wonderful Sūtra available to the English-reading world will benefit many living beings.

SarvaA Mañgalam

Tarthang Tulku

September 1994

Introduction

One of the most influential texts in Indian Mahayana Buddhist literature, the Samdhini^mocana Sūtra presents a wealth of teachings central to all Buddhist practice and philosophy. Its explications of the meaning of the ultimate, the basis-consciousness (ālaya-vijñāna), and the doctrine of cognition- only (vijñapti-mātra) have had a major impact in every country where Mahāyāna Buddhism has flourished, including India, Tibet, Mongolia, China, Korea, and Japan.

The teachings of the Buddha demonstrate how our common modes of viewing reality and our habitual ways of living and relating to the world are fundamentally mistaken. While Christian philosophy traditionally identifies the root of our existential problems as original sin, the Buddha taught that ignorance is more fundamental than sin, for through ignorance we unwittingly commit actions that result in harm to ourselves and others. This ignorance clouds the continuum of each and every being who is not a Buddha, and can be overcome only through individual effort.

The Samdhinirmocana Sūtra tells us how the full force of our mental and physical faculties can be harnessed for this task. Comprehensive and multifaceted, the text details the world view, stages, and yogic practices necessary for transforming even the most subtle manifestations of ignorance.

The reader is guided on a path that leads to mental balance, insight into the nature of reality, and deep commitment to work selflessly for the benefit of other beings.

Summary of the Text

Like many Sutras, the text recounts a series of questions and answers between the Buddha and his followers, or, in the case of chapter one, between two Bodhisattvas. Except for chapter four, where the Śrāvaka Subhūti questions the Buddha, all of the interlocutors are highly developed Bodhisattvas. Their questions and the Buddha's answers go to the very heart of the practice or issue being discussed, fully explicating profound and subtle meanings.

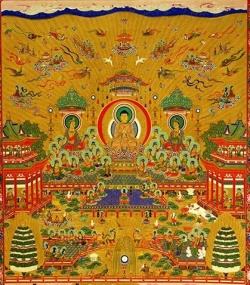

The setting in which the Buddha teaches the Sūtra is described as a vast celestial palace that fills countless worldly realms with its brilliance and surpasses all other dwellings. This wondrous palace reflects the supreme spiritual attainments of the Buddha, who created it, and the aspirations of all its inhabitants, who are Dharma practitioners of a high level of development.

The Sūtra may be divided into five main parts. The first four chapters present the ultimate and how it is to be understood by trainees. Chapter five is an analysis of consciousness; chapters six and seven discuss the relative character of phenomena and of teachings as they are illuminated by definitive understanding. The path to enlightenment is the subject of the eighth and ninth chapters, which focus on meditative practices and the methods for mastering the mental afflictions and obstacles that undermine progress on the path. Chapter ten is a discussion of the nature of a Buddha, the final goal of yogic practice.

The Bodhisattva Gambhlrarthasamdhinirmocana characterizes the ultimate as "ineffable and of a non-dual character" in chapter one. The ultimate pervades all reality but cannot be described in words or understood by conceptual thought. It is realized only by Āryas, those who have attained the path of seeing and are able to perceive the ultimate directly.

In chapter two the Bodhisattva Dharmodgata describes a debate on the ultimate character of phenomena that he witnessed among proponents of various Tīrthika systems. The Bodhisattva laments their divergent opinions, doubts, and misconceptions and marvels at the Buddha's realization and actualization of the ultimate, "whose character completely transcends all argumentation." In response, the Buddha teaches that the ultimate is realized individually, is signless, inexpressible, devoid of the conventional, and free from all dispute. Beings caught up in desire, discursiveness, and the conventions of seeing, hearing, differentiating, and perceiving, as well as beings engaged in dispute, cannot even imagine what the ultimate is like.

In chapter three, the Bodhisattva Suviśuddhamati points out that even Bodhisattvas disagree about the ultimate: Some believe the character of the ultimate and the character of the compounded are the same; others believe them to be different. Through a series of reasonings, the Buddha demonstrates that any attempt to categorize leads to error, for the ultimate is "profound and subtle, having a character completely transcending sameness and difference."

The ultimate must be sought through meditation that moves beyond all limiting and distorting categories. In chapter four the Buddha poses two questions to Subhūti: How many people communicate their spiritual understanding under the influence of conceit? How many communicate without conceit? Subhūti recounts a time when he witnessed a large gathering of monks, all advanced in training, who expressed their understanding based on "various forms of phenomena" such as the five aggregates, the six sense spheres, and the four noble truths. Since they did "not seek the ultimate whose character is all of one taste . . . therefore, these venerable persons have conceit." The Buddha explains that the ultimate, which pervades all phenomena and is undifferentiated in all compounded things, is "an object of observation for purification of the aggregates."

Using this discussion of the ultimate as a basis, chapter five provides an analysis of the nature of consciousness that indicates how we are able to progress from our present state of ignorance, desire, and hatred to the state of a Buddha. In response to questions by the Bodhisattva Viśālamati, the Buddha teaches that our present mental states and life situations result solely from our own past actions. Each action and thought creates a concordant predisposition that is deposited in our mental continuum. The Buddha points to a "basis-consciousness" which collects these predispositions and holds them until the time is ripe for them to give rise to their resultant effects. "Bodhisattvas are wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness," not only because they understand the very subtle ways that consciousness functions, but also because they have transcended even the most subtle clinging to any object of perception.

In chapter six the Buddha teaches the Bodhisattva Gunākara that phenomena exhibit a threefold character: the imputational (parikalpita), the other-dependent (paratantra), and the thoroughly established (parinispanna). These characters are illustrated by compelling examples that remind us that the Buddha is not introducing abstract philosophical concepts, but is instructing us in how to reorient the mind toward enlightenment.

In chapter seven, the Bodhisattva Paramārthasamudgata asks the Buddha his intention in teaching that "All phenomena lack own-being; all phenomena are unproduced, unceasing, quiescent from the start, and naturally in a state of nirvāna." The Buddha's response further reveals the nature of phenomena and differentiates teachings of definitive meaning from those of interpretable meaning. Just as space pervades all form, teachings of definitive meaning pervade all Sutras of interpretable meaning. Those who understand the intention behind the Buddha's teaching know that although beings are diverse, there is a "single purity" and "one vehicle."

In the eighth chapter the Bodhisattva Maitreya's questions focus on how to develop śamatha and vipaśyanā, two main bases of Buddhist meditation. Śamatha is the ability, developed through concentrated meditative practice, to focus one's mind on an object without distraction. This is essential for more advanced meditative practice, since it prevents the afflictions from arising. Vipaśyanā involves analyzing the object to determine its true nature. This practice recalls the teachings of the first four chapters, since the true nature of phenomena is the ultimate, which is equated with suchness and emptiness. Through developing vipaśyanā, one eradicates the basis of the afflictions and is able to perceive the ultimate directly. Here the Buddha teaches that the images of people and things that we observe are "cognition-only."

The ninth chapter maps the path to enlightenment, delineating the ten Bodhisattva stages, the levels through which Mahāyāna practitioners progress. Each stage represents a decisive advance in understanding and spiritual attainment. The questioner here is Avalokiteśvara, the embodiment of compassion. The main meditative practice is the six perfections— generosity, ethics, patience, effort, concentration, and wisdom—the essence of the Bodhisattva's training.

Compassion motivates Bodhisattvas to work tirelessly on the spiritual path for an unimaginably long period of time. The final fruition of their efforts is the state of a Buddha, the focus of chapter ten. It represents the apex of all spiritual qualities and the highest development of compassion and wisdom. Through the Buddha's answers to the Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī's questions, we learn that a Buddha's limitless compassionate action is accomplished without any manifest activity. There is no afflicted being who later becomes purified: "Afflicted phenomena and pure phenomena are all without activity and personhood." Hearing this, the aspiring Bodhisattva is again reminded that pursuing the ultimate goal of the path of yogic practice begins and ends with a proper understanding of the nature of the ultimate.

About This Translation

As this brief summary suggests, the Samdhinirmocana Sūtra is a complex and advanced text. Translating it has proven to be a demanding task which has taken many years. I first began work on the translation as a graduate student at the University of Virginia, where it became my doctoral thesis. Later much effort was devoted to refining the translation and preparing it for publication. Throughout, my goal has been to keep the English translation faithful to the structure of the Tibetan text and to translate technical terms conservatively and consistently. While this has sometimes resulted in awkward readings, I prefer this approach to being overly speculative about the meaning of the Sutra's many difficult passages.

Although the original Sanskrit text was probably lost by the thirteenth century, numerous translations of this Sūtra exist today in Asian languages. I chose to base this translation on the Tibetan since I had access to a number of different Tibetan editions, and also because the Tibetans are especially noted for their accurate translations of canonical texts. In my studies, I have consulted ten different Tibetan editions, as well as three Chinese editions, and have noted their variant readings.

The Tibetan text presented here is reproduced from the canonical edition found in the sDe-dge bKa'-'gyur, which is highly esteemed by Tibetan scholars, and the English translation is based on this text. It is my hope that having the Tibetan text facing the English translation will encourage students and scholars to draw inspiration and clarity from both.

In preparing the translation and notes, I have also relied on the five commentaries found in the Tibetan Buddhist Canon, as well as on Tibetan exegetical materials (both written texts and oral instructions), and on Yogācāra texts that explain concepts presented in the Sūtra.

Most of the footnotes are drawn from the two most comprehensive commentaries in Tibetan. The larger of these is a three-volume work authored by Wonch'uk, a Korean student of the great Chinese scholar Hsūan-tsang. Since major sections of Wonch'uk's original Chinese text have been lost, the only complete version of the text available today is the Tibetan translation found in the Tibetan Buddhist Canon.

The text is a masterpiece of traditional Buddhist scholarship that draws upon a vast range of Buddhist literature, cites many different opinions, raises important points about the thought of the Sūtra, and provides explanations of virtually every technical term and phrase.

The other major commentary, consisting of two volumes, is signed by "Byang-chub-rdzu-'phrul." Although there is some mystery surrounding the author's identity, most Tibetan scholars attribute this text to Cog-ro Klu'i-rgyal-mtshan, a renowned eighth-century Tibetan translator and scholar. The text provides insightful explications of most of the Sūtra.

Other sources consulted for the notes include the works of Asañga and his brother Vasubandhu (generally considered to be the main exponents and systematizers of the Yogācāra school); commentaries on their works by Sthiramati and Sumatiśīla; the commentary on the eighth chapter attributed to Jñanagarbha; the Legs-bshad-snying-po (which mainly focuses on the seventh chapter of the Sūtra) by Tsong-kha-pa, founder of the dGe-lugs-pa school of Tibetan Buddhism; its commentary by dPal-'byor-lhun-grub; and oral explanations from contemporary Tibetan scholars.

I am truly fortunate to have had access to such a wide range of secondary materials and explanations, for the meanings expressed in the Sūtra can be obscure. Each source has helped me greatly in understanding and translating the Sūtra. While the constraints of space have made it necessary to condense the notes prepared for my doctoral thesis, I hope that the notes included here will inspire readers to consider the many differing perspectives available and foster a deeper understanding of the Sutra's meaning.

I have also had the great good fortune to have worked with Tibetan and Western scholars who generously shared their knowledge and understanding of this Sūtra with me. I would especially like to thank Geshe Jamphel Phandro, Geshe Palden Dragpa, Geshe Yeshe Thabkhe, Dr. Jeffrey Hopkins, Dr. Christian Lindtner, Dr. Ernst Steinkellner, and Dr. Helmut Eimer. I am also grateful to H. H. the Dalai Lama for his illuminating remarks on this Sūtra during a meeting in Dharamsala in 1988.

Taught by the Buddha as a skillful means, the Samdhinirrnocana Sūtra is intended as a basis for meditative practice, a guide to a Bodhisattva's training for enlightenment. Bearing this in mind may encourage the reader to undertake the careful and sustained study, contemplation, and application in daily life that will ultimately help to reveal the full depth and scope of this profound work.

The Chapter of Gambhīrārthasamdhinirmocana

The Setting and Chapter One

Homage to all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas!

Thus have I heard at one time: The Bhagavan was dwelling in an immeasurable palace arrayed with the supreme brilliance of the seven precious substances,[1] emanating great rays of light that suffused innumerable universes. Well-apportioned into distinctive sections, it was limitless in reach;[2] an unimpeded mandala; a sphere of activity completely transcending the three worldly realms; arisen from the root of supreme virtue that transcends the world.[3] It was characterized by perfect knowledge, the knowledge of one who has mastery.[4]

Abode of the Tathāgata, attended by a community of innumerable Bodhisattvas,[5] it was alive with unlimited numbers of devas, nāgas, yakças, gandharvas, asuras, garudas, kimnaras, rnahoragas, humans, and non-humans.[6] Steadfast due to great bliss and joy in the taste of the Dharma; enduring in order to bring about the welfare of all sentient beings; free from the harm of the defilements of the afflictions; completely free from all demons;[7] surpassing all patterns; arranged through the blessing of the Tathāgata; emancipated through great mindfulness, intelligence, and realization; support of the great state of peace and penetrating awareness; entered through the great doors of liberation—emptiness, signlessness, and wishlessness- this pattern was adorned with boundless masses of excellent qualities, and with great kingly jeweled lotuses.[8]

The Bhagavan was endowed with a mind of good understanding and did not possess the two (negative) behaviors.[9] Perfectly absorbed in the teaching of signlessness, abiding in the way that a Buddha abides,[10] having attained sameness with all Buddhas, having full realization without obscurations, he was endowed with irreversible qualities.[11] Not captivated by objects of activity, positing (doctrines) inconceivably,[12] thoroughly penetrating the sameness of the three times, the (Bhagavan) was endowed with the five (types of) embodiments that abide in every worldly realm.

Having attained the knowledge that has no doubts regarding all phenomena, having attained intelligence possessing all capabilities, he was unperplexed with respect to knowledge of the Dharma. Endowed with an unimaginable embodiment,[13] having fully given rise to the wisdom of all the Bodhisattvas, endowed with the non-dual abiding of a Buddha[14] and the supreme perfections, he had reached the limit of the uniquely liberating and exalted wisdom of a Tathāgata. He had realized full equality with the state of a Buddha without ends or middle, wholly permeated by the Dharmadhātu, extending to the limit of the realm of space.[15]

He was also accompanied by a measureless assembly of Śrāvakas, all very knowledgeable sons of the Buddha, with liberated minds,[16] very liberated wisdom, and completely pure ethics. They happily associated with those who yearn for the teaching. They were very learned, bearing in mind what they had learned, accumulating learning, intent on good contemplations, speaking good words, and doing good deeds. They had agile wisdom, quick wisdom, sharp wisdom, the wisdom of renunciation, the wisdom of certain realization, great wisdom, extensive wisdom, profound wisdom, wisdom without equal. Endowed with the precious jewel of wisdom, they possessed the three knowledges[17] and had obtained supremely blissful abiding in this life and great purity. They had fully developed a completely peaceful way of acting, were endowed with great patience and determination, and were wholly engaged in the Tathāgata's teaching.

Also in attendance were innumerable Bodhisattvas who assembled from various Buddha lands, all of them fully engaged and abiding in the great state (of the Mahāyāna).[18] They had renounced cyclic existence through the teaching of the Great Vehicle, were even-minded toward all beings, and were free from all imputations, ideations, and mental constructions. They had conquered all demons and opponents and were removed from all the mental tendencies of the Śrāvakas and Pratyekabuddhas. They were steadfast through great bliss and joy in the taste of the Dharma. They had completely transcended the five great fears[19] and had progressed solely to the irreversible stages.[20] They had actualized those stages which bring to rest all harms to all sentient beings.

Among them were the Bodhisattvas, the Mahāsattvas, Gambhīrārthasamdhinirmocana and Vidhivatpariprcchaka, Dharmodgata, Suviśuddhamati, Viśālamati and Gunākara, Paramārthasamudgata and Āryāvalokiteśvara, Maitreya and Mañjuśrī, all abiding together.

At that time, Bodhisattva Vidhivatpariprcchaka questioned the Bodhisattva Gambhīrārthasamdhinirmocana[21] about the ultimate whose character is inexpressible and non-dual. "O Son of the Conqueror, when it is said, 'All phenomena are nondual, all phenomena are non-dual,' how is it that all phenomena are non-dual?"

"Son of good lineage, with respect to all phenomena, 'all phenomena' are of just two kinds: compounded and uncompounded.uncompounded. The uncompounded is not uncompounded, nor is it compounded."

"O son of the Conqueror, why is the compounded neither compounded nor uncompounded? Why is the uncompounded neither uncompounded nor compounded?"

"Son of good lineage, 'compounded' is a term designated by the Teacher. This term designated by the Teacher is a conventional expression arisen from mental construction.

Because a conventional expression arisen from mental construction is a conventional expression of various mental constructions, it is not established. Therefore, it is (said to be) not compounded.

"Son of good lineage, 'uncompounded' is also included within the conventional. Even if something were expressed that is not included within the compounded or uncompounded it would be just the same as this. It would be just like this. An expression is also not without thingness. What is a thing? It is that to which the Āryas completely and perfectly awaken without explanation, through their exalted wisdom and exalted vision.[22] Because they have completely and perfectly realized that very reality which is inexpressible, they designate the name 'compounded'.

"Son of good lineage, 'uncompounded' is also a term designated by the Teacher. This term designated by the Teacher is a conventional expression arisen from mental construction. Because a conventional expression arisen from mental construction is a conventional expression of various mental constructions, it is not established. Therefore, it is (said to be) not uncompounded.

"Son of good lineage, 'compounded' is also included within the conventional. Even if something were expressed that is not included within the compounded or uncompounded it would be just the same as this. It would be just like this. An expression is also not without thingness. What is a thing? It is that to which the Āryas completely and perfectly awaken without explanation, through their exalted wisdom and exalted vision. Because they have completely and perfectly realized that very reality which is inexpressible, they designate the name 'uncompounded'."

"O son of the Conqueror, how is it that the Āryas, through their exalted wisdom and exalted vision completely and perfectly realize things without explanation, and completely and perfectly realize that very reality which is inexpressible and therefore designate the names 'compounded' and 'uncompounded'?"

"Son of good lineage, for example, a magician or a magician's able student, standing at the crossing of four great roads, after gathering grasses, leaves, twigs, pebbles or stones, displays various magical forms, such as a herd of elephants, a cavalry, chariots, and infantry; collections of gems, pearls, lapis lazuli, conch-shells, crystal, and coral; collections of wealth, grain, treasuries, and granaries.[23]

"When those sentient beings who have childish natures, foolish natures, or confused natures—who do not realize that these are grasses, leaves, twigs, pebbles, and stones—see or hear these things, they think: 'This herd of elephants that appears, exists; these cavalry, chariots, infantry, gems, pearls, lapis lazuli, conch-shells, crystal, coral, wealth, grain, treasuries, and granaries that appear, exist.'

"Having thought this, they emphatically apprehend and emphatically assert in accordance with how they see and hear. Subsequently they make the conventional designations: 'This is true, the other is false.' Later they must closely examine these things.

"When those sentient beings who do not have childish or foolish natures, who have natures endowed with wisdom— who recognize that these are grasses, twigs, pebbles, and stones—hear and see these things, they think: 'This herd of elephants that appears does not exist. These cavalry, chariots, infantry, gems, pearls, lapis lazuli, conch-shells, crystal, coral, wealth, grain, treasuries, and granaries that appear do not exist. But, in regard to them there arises the perception of a herd of elephants and the perception of the attributes of a herd of elephants, the perception of wealth, grain, treasuries, and granaries and the perception of their attributes. These magical illusions exist.'

"Having thought, 'These visual deceptions exist,' they emphatically apprehend and emphatically assert in accordance with how they see and hear. Subsequently they do not make the conventional designations: 'This is true, the other is false.' They make conventional designations because they fully know the object in this way. Later, they will not need to closely examine these things.

"Similarly, when sentient beings who are ordinary beings with childish natures—who have not attained the supramundane wisdom of Āryas, who do not manifestly recognize the inexpressible reality of all phenomena—see and hear these compounded and uncompounded things, they think: 'These compounded and uncompounded things which appear, exist.' They emphatically apprehend and emphatically assert in accordance with how they see and hear. Subsequently they make the conventional designations: 'This is true, the other is false.' Later they must closely examine these things.

"When those sentient beings who do not have childish natures—who see the truth, who have attained the supramundane wisdom of the Āryas, who manifestly recognize the inexpressible reality of all phenomena—see and hear these compounded and uncompounded things, they think: 'These compounded and uncompounded things that appear do not exist.' With regard to them there arises a perception of what is compounded and uncompounded and a perception of the attributes of the compounded and the uncompounded.

"Thinking that, 'The compositional signs that arise from mental constructions exist like a magician's illusions; these obscurations of the mind exist,' they emphatically apprehend and emphatically assert in accordance with how they see and how they hear. But they do not subsequently make the conventional designations: 'This is true, the other is false.' They make conventional designations because they fully know the object in this way. Later, they will not need to closely examine these things.

"Son of good lineage, in that way the Āryas, through exalted wisdom and exalted vision, completely and perfectly realize things without explanation. Because they completely and perfectly realize that very reality which is inexpressible, they nominally designate the names 'compounded' and 'uncompounded'." Then Bodhisattva Gambhīrārthasamdhinirmocana spoke these verses:

"The Conquerors taught that the profound, inexpressible and non-dual, is not the domain of children, but childish ones, obscured by ignorance, delight in elaborations of speech and abide in duality.[24]

"Those who do not realize this or who understand it wrongly will be reborn as sheep or oxen. Having abandoned the speech of the wise, they cycle in samsāra for a very long time."

This completes the first chapter of the Bodhisattva Gambhīrārthasamdhinirmocana.

The Questions of Dharmodgata

Chapter Two

Jhen Bodhisattva Dharmodgata[25] spoke to the Bhagavan: "Bhagavan, in a distant epoch of ancient times, passing beyond this world system as many world systems as there are grains of sand in seventy-seven Ganges rivers, I lived in the world system Kīrtimat, Buddha Land of the Tathāgata Viśālakīrti. While there, I saw 7,700,000 teachers and others of various Tīrthika systems.[26]

"They had gathered together at a certain place to begin considering the ultimate character of phenomena. Although they contemplated, weighed, closely examined, and sought the ultimate character of phenomena, they had not realized it. They had divergent opinions, doubts, and misconceptions. They debated and quarreled; they insulted each other with harsh words; they were abusive, deceitful, and overbearing; they attacked one another.

"Having seen them so divided, Bhagavan, I thought: 'Alas! Tathāgatas arise in the world and through their arising the realization and actualization of the ultimate, whose character completely transcends all argumentation, is indeed marvelous and astonishing!'"

The Bhagavan replied to the Bodhisattva Dharmodgata: "So it is! Dharmodgata, so it is! I have fully and perfectly realized the ultimate whose character completely transcends all argumentation.[27] Having fully and perfectly realized this, I have proclaimed it and made it clear, opened it up and systematized it, and taught it comprehensively.

"Why is this? I have explained that the ultimate is realized individually by the Āryas,[28] while objects collectively known by ordinary beings (belong to) the realm of argumentation. Thus, Dharmodgata, by this form of explanation know that whatever has a character completely transcending all argumentation is the ultimate.

"Moreover, Dharmodgata, I have explained that the ultimate belongs to the signless realm, while argumentation belongs to the realm of signs. Thus, Dharmodgata, by this form of explanation also know that whatever has a character completely transcending all argumentation is the ultimate.

"Moreover, Dharmodgata, I have explained that the ultimate is inexpressible, while argumentation belongs to the realm of expression. Thus, Dharmodgata, by this form of explanation also know that whatever has a character completely transcending all argumentation is the ultimate.

"Moreover, Dharmodgata, I have explained that the ultimate is devoid of conventions, while argumentation belongs to the realm of conventions.[29] Thus, Dharmodgata, by this form of explanation also know that whatever has a character completely transcending all argumentation is the ultimate.

"Moreover, Dharmodgata, I have explained that the ultimate is completely devoid of all dispute, while argumentation belongs to the realm of controversy. Thus, Dharmodgata, by this form of explanation also know that whatever has a character completely transcending argumentation is the ultimate. "Dharmodgata, for example,[30] beings acquainted only with hot and bitter tastes for their entire lives would be unable to imagine, infer, or appreciate the sweet taste of honey or the taste of sugar.

"Beings who have been engaged in passionate desire for a long time, who have been utterly tormented by the pangs of desire, are unable to imagine, infer, or appreciate the happiness of inner solitude free from all the signs of form, sound, smell, taste, or touch.

"Because beings have been engaged in discursiveness for a long time, manifestly delighting in discursiveness, they are unable to imagine, infer, or appreciate the inner non-discursive joy of the Āryas.

"Because beings have been engaged in the conventions of seeing, hearing, differentiating, and perceiving for a long time, manifestly delighting in these conventions, they are unable to imagine, infer, or appreciate nirvāria, which is the cessation of (belief in) true personhood,[31] the complete elimination of all conventions.

"Dharmodgata, for instance, because beings have devoted their energy to dispute for a long time through strongly holding onto 'mine', manifestly delighting in dispute, they are unable to imagine, infer, or appreciate the absence of dispute or the absence of strongly holding onto 'mine' (like those who dwell) in Uttarakuru.[32]

"Accordingly, Dharmodgata, all disputants are unable to imagine, infer, or appreciate the ultimate whose characteristic completely transcends all argumentation." Then the Bhagavan spoke this verse:

"The realm with an individually realized character

is ineffable and devoid of conventions.

Ultimate reality is free from dispute,

a character that transcends all argument."

This completes the second chapter of Dharmodgata.

The Questions of Suviśuddhamati

Chapter Three

Then Bodhisattva Suviśuddhamati[33] spoke to the Bhagavan: "Bhagavan, regarding what the Bhagavan formerly said: 'The ultimate, profound and subtle, having a character completely transcending sameness and difference, is difficult to realize.' What the Bhagavan has spoken so eloquently in this way is truly wondrous.

"Bhagavan, concerning this, once at a certain place I saw a great many Bodhisattvas who had entered the stage of engagement through conviction.[34] They had gathered together to set about considering the difference or non-difference of the compounded and the ultimate.

"Once they had assembled, a certain Bodhisattva said, 'The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are not different.'

"Another said, 'It is not the case that the character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are not different: The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are different.'

"Another became uncertain and full of doubts and said, 'There are those who say, "The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are different," and those who say, "The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are not different." Which of these Bodhisattvas is truthful, which is mistaken? Which is properly oriented, which is improperly oriented?'

"Bhagavan, having seen these things, I thought this: 'All these sons and daughters of good lineage have not sought out the ultimate, the subtle character completely transcending difference or non-difference from compounded things. They are all childish, obscured, unclear, unskilled, and they are not properly oriented.'"[35]

The Bhagavan replied to the Bodhisattva Suviśuddhamati: "So it is! Suviśuddhamati, so it is! All these sons and daughters of good lineage do not understand the ultimate, the subtle character completely transcending difference or non-difference from compounded things. They are all childish, obscured, unclear, unskilled, and not properly oriented.

"Why is this? Suviśuddhamati, it is because those who investigate the compounded in that way neither realize the ultimate nor do they manifest the ultimate.

"Why is this? Suviśuddhamati, if the character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate were not different, then, because of that, even all ordinary childish beings would see the truth and, while still mere ordinary beings, would attain (the highest achievement) and would even achieve the highest bliss of nirvana. Moreover, they would completely and perfectly realize unsurpassed, perfect enlightenment.

"If the character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate were different, then, because of that, even those who see the truth would not be free from the signs of the compounded.

"Since they would not be free from the signs of the compounded, even those who see the truth would not be liberated from the bondage of signs. If they were not liberated from the bondage of signs, then they would also not be liberated from the bondage of errant tendencies.[36] If they were not liberated from these two bonds, then those who see the truth would not attain (the highest achievement), and would not achieve the highest bliss of nirvāna. Furthermore, they would not completely and perfectly realize unsurpassed, perfect enlightenment.

"Suviśuddhamati, since ordinary beings are not seers of truth, they are merely ordinary beings. They have not attained (the highest achievement), nor have they achieved the highest bliss of nirvana. Further, they have not completely and perfectly realized unsurpassed, perfect enlightenment. Therefore, it is not suitable to say, 'The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are not different.' Know by this form of explanation that those who say, 'The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are not different' are improperly oriented; their orientation is incorrect.

"Suviśuddhamati, it is not the case that seers of truth are free from the signs of the compounded; they are simply free. Moreover, seers of truth are not liberated from the bondage of signs, but they are liberated. Seers of truth are not liberated from the bondage of errant tendencies, but they are liberated.

"Since they are liberated from these two bonds, they attain the highest achievement. With unexcelled bliss they attain nirvana and also completely and perfectly realize unsurpassed enlightenment. Therefore, it is not suitable to say, 'The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are different.'

"Know by this form of explanation that those who say, 'The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are different' are improperly oriented; their orientation is incorrect.

"Moreover, Suviśuddhamati, if the character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate were not different, then just as the character of the compounded would be included in the afflicted character, the character of the ultimate would also be included in the afflicted character.

"Suviśuddhamati, if the character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate were different, then the ultimate character within all characters of compounded things would not be their general character.

"Suviśuddhamati, since the character of the ultimate is not included in the character of the afflicted, and the ultimate character in all characters of compounded things is their general character, it is neither suitable to say, 'The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are not different,' nor is it suitable to say, 'The character of the ultimate is different.

"Know by this form of explanation that those who say, 'The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are not different' and those who say, 'The character of the ultimate is different' are improperly oriented; their orientation is incorrect.

"Moreover, Suviśuddhamati, if the character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate were not different, then just as the ultimate character does not differ within all characters of compounded things, so also all the characters of compounded things would not differ. Even yogis would not search for an ultimate beyond compounded things as they are seen, heard, differentiated, and known.

"If the character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate were different, then just the absence of self and just the absence of an own-being of compounded things would not be the ultimate character (of those phenomena).

The afflicted character and the purified character would also be established as simultaneously having different characters.

"Suviśuddhamati, since the characters of the compounded both differ and do not differ, yogis search for an ultimate beyond all compounded things as they are seen, heard, differentiated, and known. The ultimate is distinguished by being the selflessness of compounded things. Further, the afflicted character and the purified character are not established as simultaneously having different characters. Therefore, it is not suitable to say that the character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are either 'notdifferent' or 'different'.

"Also know by this form of explanation that those who say, 'The character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate are not different,' and those who say, They are different' are improperly oriented; their orientation is incorrect. "Suviśuddhamati, for instance, it is not easy to designate the whiteness of a conch as being a character that is different from the conch or as being a character that is not different from it.[37] As it is with the whiteness of a conch, so it is with the yellowness of gold.

"It is also not easy to designate the melodiousness of the sound of the vmā[38] as being either a character that is not different from the sound of the vmā or as being a character that is different (from it). It is also not easy to designate the fragrant smell of the black agaru tree[39] as being a character that is not different from the black agaru tree or as being a character that is different from it.

"Similarly, it is not easy to designate the heat of pepper as being a character that is not different from pepper or as being a character that is different (from it). As it is with the heat of pepper, so it is also with the astringency of myrobalan arjuna.[40]

"For instance, it is not easy to designate the softness of cotton as being either a character that is not different from the cotton or a character that is different (from it). For instance, it is not easy to designate clarified butter as being either a character that is not different from butter or a character that is different from it. For instance, it is not easy to designate the impermanence in all compounded things, or the suffering in all contaminated things, or the selflessness in all phenomena as being characters that are not different from those things or characters that are different from them.

"Suviśuddhamati, for instance, it is not easy to designate the agitating character of desire and the character of affliction as being a character that is not different from desire or a character that is different (from it). Know that just as it is with desire, so it is with hatred and also obscuration.

"Similarly, Suviśuddhamati, it is not appropriate to designate the character of the compounded and the character of the ultimate as being either characters that are not-different or characters that are different.

"Suviśuddhamati, in that way I have completely and perfectly realized the ultimate, which is subtle, supremely subtle, supremely profound, difficult to realize, supremely difficult to realize, and which is a character that completely transcends difference and non-difference. Having completely and perfectly realized this, I have proclaimed it and made it clear, opened it up, systematized it, and taught it comprehensively." Then the Bhagavan spoke these verses:

"The character of the compounded realm and of the ultimate

is a character devoid of sameness and difference.

Those who impute sameness and difference

are improperly oriented.

"Cultivating śamatha and vipaśyanā,

beings will be liberated from

the bonds of errant tendencies

and the bonds of signs."

This completes the third chapter of Suviśuddhamati.

The Questions of Subhūti

Chapter Four

Then the Bhagavan spoke to the venerable Subhuti:[41] "Subhūti, in the realms of sentient beings, how many sentient beings do you think there are who communicate their understanding under the influence of conceit? In the realms of sentient beings, how many sentient beings do you think there are who communicate their understanding without conceit?"[42]

Subhūti replied: "Bhagavan, I think that in the realms of sentient beings, those sentient beings who communicate their understanding without conceit are few. Bhagavan, I think that in the realms of sentient beings, sentient beings who communicate their understanding under the influence of conceit are immeasurable, countless, and inexpressible (in number).

"Bhagavan, at one time I lived in a great forest hermitage. Dwelling with me in that great forest hermitage were numerous monks. Early one morning, I saw the monks gather together. At that time, they communicated their understanding by describing what they had manifestly realized through observing the various forms of phenomena. One communicated his understanding based on observing the (five) aggregates: observing the signs of the aggregates, observing the arising of the aggregates, observing the disintegration of the aggregates, observing the cessation of the aggregates, and observing the actualization of the cessation of the aggregates.[43]

"Just as this one communicated his understanding based upon observing the aggregates, another did so based upon observing the sense spheres. Another did so based on observing dependent origination. Another communicated his understanding based on observing the (four) sustenances: observing the signs of the sustenances, observing the arising of the sustenances, observing the disintegration of the sustenances, observing the cessation of the sustenances, and observing the actualization of the cessation of the sustenances.[44]

"Another communicated his understanding based on observing the (four) truths: observing the signs of the truths, observing realization of the truth (of suffering), observing the truth of the abandonment (of the source of suffering), observing actualization of the truth (of the cessation of suffering), and observing meditative cultivation of the truth (of the path).[45]

"Another communicated his understanding based on observing the constituents: observing the signs of the constituents, observing the various constituents, observing the manifold constituents, observing the cessation of the constituents, and observing the actualization of the cessation of the constituents.[46]

"Another communicated his understanding based on observing the (four) mindful establishments: observing the signs of the mindful establishments, observing the discordances to the mindful establishments and the antidotes, observing the meditative cultivation of the mindful establishments, observing the arising of the mindful establishments that have not yet arisen, and observing the abiding, non-forgetting, continued arising, and increasing and extending of the mindful establishments that have arisen.[47]

"Just as that one (observed) the mindful establishments, others (observed) the (four) correct abandonings, the (four) bases of magical abilities, the (five) powers, the (five) forces, and the (seven) branches of enlightenment. Another one communicated his understanding based on observing the eight branches of the path of the Āryas: observing the signs of the eight branches of the path of the Āryas, observing the antidotes to the discordances to the eight branches of the path of the Āryas, observing the meditative cultivation of the eight branches of the path of Āryas, observing the arising of the eight branches of the path of Āryas that have not yet arisen, and observing the abiding, non-forgetting, continued arising, and increasing and extending of the eight branches of the path of the Āryas that have arisen.[48]

"Having seen them, I thought: 'These venerable persons communicate their understandings by describing their manifest realization of the various forms of phenomena, and, in this way, they do not seek the ultimate whose character is all of one taste.[49] Therefore, these venerable persons have conceit; they can only communicate their understanding under the influence of conceit.'

"Bhagavan, regarding what the Bhagavan formerly said: 'The ultimate is profound and subtle, very difficult to realize, supremely difficult to realize, and it is of a character that is all of one taste.' What the Bhagavan said so eloquently in this way is wondrous.

"Bhagavan, regarding those who have entered into this very teaching by the Bhagavan that the ultimate is of a character that is everywhere of one taste: Since those sentient beings who are monks have difficulty in understanding in this way, what need is there to mention Tīrthikas who are outside of this (teaching)?"

The Bhagavan replied: "So it is! Subhūti, so it is! I have perfectly and completely realized the ultimate having a character that is all of one taste, which is subtle, supremely subtle, profound, supremely profound, difficult to realize, supremely difficult to realize. Having perfectly and manifestly realized this, I have proclaimed it and made it clear, opened it up and systematized it, and taught it comprehensively.

"Why is this so? Subhūti, I teach that the object of observation for purification of the aggregates is the 'ultimate'.[50] Also, Subhūti, I teach that the ultimate is an object of observation for purification of the sense spheres, dependent origination, the sustenances, the truths, the constituents, the mindful establishments, the correct abandonings, the bases of magical abilities, the powers, the forces, the branches of enlightenment, and, Subhūti, the eight branches of the path of the Âryas. That which is an object of observation for purification of the aggregates is all of one taste; its character does not differ.

"Just as it is with the aggregates, so also that which is the object of observation for purification of (phenomena) ranging from the sense spheres up to the eight branches of the path of the Âryas is all of one taste: Its character does not differ.

Therefore, Subhūti, know by this form of explanation that whatever is of a character that is all of one taste is the ultimate. "Moreover, Subhūti, monks who practice yoga, having completely realized the suchness of one aggregate, the selflessness of phenomena that is the ultimate, do not have to seek further for suchness, for the ultimate, and for selflessness in each of the other aggregates, or in the constituents, the sense spheres, dependent origination, in the sustenances, the truths, the mindful establishments, in the correct abandonings, the bases of magical abilities, in the powers, the forces, the branches of enlightenment, or in each of the eight branches of the path of the Āryas.

"They rely on the non-dual understanding that follows suchness. Through just that, they definitely apprehend and manifestly realize the ultimate which is of a character that is all of one taste. Therefore, Subhūti, also know by this form of explanation that whatever is of a character that is all of one taste is the ultimate.

"Furthermore, Subhūti, the aggregates, sense spheres, dependent origination, sustenances, truths, constituents, mindful establishments, correct abandonings, bases of magical abilities, powers, forces, and branches of enlightenment are of mutually different characters, just as the eight branches of the path of the Āryas are of mutually different characters. If, in the same way, the suchness of these phenomena, the ultimate, the selflessness of phenomena were also of different characters, then suchness, the ultimate, the selflessness of phenomena would also be associated with causes and would be produced from causes. If it were produced from causes, it would be compounded. If it were compounded, it would not be the ultimate. If it were not the ultimate it would be necessary to search for another ultimate.

"Therefore, Subhūti, the ultimate, the selflessness of phenomena, is not produced from causes and is not compounded. It is not that which is not the ultimate, and it is not necessary to search for an ultimate other than that ultimate.

"Whether Tathāgatas arise or do not arise, because phenomena abide in permanent, permanent time and in everlasting, everlasting time, the sphere of reality of phenomena alone abides.[51] Therefore, Subhūti, know by this form of explanation that whatever is of a character that is all of one taste is the ultimate.

"Subhūti, for example, with respect to the differing signs, the manifold various aspects of form, space is signless, nonconceptual, and unchanging. It is of a character that is all of one taste. Similarly, Subhūti, with respect to phenomena that are of different characters, the ultimate is also to be viewed as being of a character that is all of one taste."[52]

Then the Bhagavan spoke this verse:

"Buddhas teach that the ultimate is undifferentiated

and is of a character all of one taste.

Those who conceptualize difference within it

abide in conceit and are obscured."

This completes the fourth chapter of Subhūti.

The Questions of Viśālamati

Chapter Five

Then Bodhisattva Viśalamati[53] questioned the Bhagavan: "Bhagavan, when you say, 'Bodhisattvas are wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness; Bodhisattvas are wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness,' Bhagavan, just how are Bodhisattvas wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness?[54] For what reason does the Tathāgata designate a Bodhisattva as wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness?"

The Bhagavan replied to the Bodhisattva Viśālamati: "Viśālamati, you are involved in (asking) this in order to benefit many beings, to bring happiness to many beings, out of sympathy for the world, and for the sake of the welfare, benefit, and happiness of many beings, including gods and humans. Your intention in questioning the Tathāgata about this subject is good. It is good! Therefore, Viśālamati, listen well and I will describe for you the way (Bodhisattvas) are wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness.

"Viśālamati, whatever type of sentient being there may be in this cyclic existence with its six kinds of beings, those sentient beings manifest a body and arise within states of birth such as egg-born, or womb-born, or moisture-born, or spontaneously- born.[55]

"Initially, in dependence upon two types of appropriation— the appropriation of the physical sense powers associated with a support and the appropriation of predispositions which proliferate conventional designations with respect to signs, names, and concepts—the mind which has all seeds ripens; it develops, increases, and expands in its operations.[56] Although two types of appropriation exist in the form realm, appropriation is not twofold in the formless realm.[57]

"Viśālamati, consciousness is also called the 'appropriating consciousness' because it holds and appropriates the body in that way.[58] It is called the 'basis-consciousness' because there is the same establishment and abiding within those bodies.[59] Thus they are wholly connected and thoroughly connected. It is called 'mind' because it collects and accumulates forms, sounds, smells, tastes, and tangible objects.[60]

"Viśālamati, the sixfold collection of consciousness—the eye consciousness, ear consciousness, nose consciousness, tongue consciousness, body consciousness, and mind consciousness— arises depending upon and abiding in that appropriating consciousness. An eye consciousness arises depending on an eye and a form in association with consciousness. Functioning together with that eye consciousness, a conceptual mental consciousness arises at the same time, having the same objective reference.

"Viśālamati, (an ear consciousness, a nose consciousness, a tongue consciousness, and) a bodily consciousness arise depending on an ear, a nose, a tongue, and a body in association with consciousness and (sound, smell, taste, and) tangibles. Functioning together with (nose, ear, tongue, and bodily) consciousness, a conceptual mental consciousness arises at the same time, having the same objective reference.

"If there arises one eye consciousness, there arises together with it only one mental consciousness, which has the same object of activity as the eye consciousness. Likewise, if two, three, four, or five consciousnesses arise together, then there still arises, together with them, only one conceptual mental consciousness, which has the same object of activity as the fivefold collection of consciousness.

"Viśālamati, for example, if the causal conditions for the arising of one wave in a great flowing river are present, then just one wave will arise. If the causal conditions for two waves or many waves are present, then multiple waves will arise. But the river's own continuity will not be broken; it will never be entirely stopped.

"If the causal conditions for the arising of a single image in a perfectly clear round mirror are present, then just one image will arise. If the causal conditions for the arising of two images or of many images are present, then multiple images will arise. However, that round mirror will not be transformed into the nature of the image; they will never be fully linked. "Viśālamati, just as it is with the water and the mirror, if, depending upon and abiding in the appropriating consciousness, the causal conditions for the simultaneous arising of one eye consciousness are present, then just one eye consciousness will arise one time. If the causal conditions for the single arising of up to the fivefold assemblage of consciousness are present, then up to that fivefold assemblage of consciousness will also arise one time.

"Viśālamati, it is like this: Bodhisattvas who rely on knowledge of the system of doctrine and abide in knowledge of the system of doctrine are wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness. However, when the Tathāgata designates Bodhisattvas as being wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness, it is not only because of this that he designates those Bodhisattvas as being (wise) in all ways.[61]

"Viśālamati, those Bodhisattvas (wise in all ways) do not perceive their own internal appropriators; they also do not perceive an appropriating consciousness, but they are in accord with reality. They also do not perceive a basis, nor do they perceive a basis-consciousness. They do not perceive accumulations, nor do they perceive mind. They do not perceive an eye, nor do they perceive form, nor do they perceive an eye-consciousness. They do not perceive an ear, nor do they perceive a sound, nor do they perceive an ear-consciousness. They do not perceive a nose, nor do they perceive a smell, nor do they perceive a nose-consciousness. They do not perceive a tongue, nor do they perceive a taste, nor do they perceive a tongue consciousness. They do not perceive a body, nor do they perceive a tangible object, nor do they perceive a bodily consciousness. Viśālamati, these Bodhisattvas do not perceive their own particular thoughts, nor do they perceive phenomena, nor do they perceive a mental consciousness, but they are in accord with reality. These Bodhisattvas are said to be 'wise with respect to the ultimate'. The Tathāgata designates Bodhisattvas who are wise with respect to the ultimate as also being 'wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness'.

"Viśālamati, this is how Bodhisattvas are wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness. When the Tathāgata designates Bodhisattvas as being 'wise with respect to the secrets of mind, thought, and consciousness', he designates them as such for this very reason."

Then the Bhagavan spoke this verse:

"If the appropriating consciousness, deep and subtle,

all its seeds flowing like a river,

were conceived as a self, that would not be right.

Thus I have not taught this to children."[62]

This completes the fifth chapter of Viśālamati.

The Questions of Gunākara

Chapter Six

Then Bodhisattva Gunakara[63] questioned the Bhagavan: "Bhagavan, when you say 'Bodhisattvas are wise with respect to the character of phenomena; Bodhisattvas are wise with respect to the character of phenomena,' Bhagavan, just how are Bodhisattvas wise with respect to the character of phenomena? For what reason does the Tathāgata designate a Bodhisattva as being wise with respect to the character of phenomena?"

The Bhagavan replied to the Bodhisattva Gunākara: "Gunākara, you are involved in (asking) this in order to benefit many beings, to bring happiness to many beings, out of sympathy for the world, and for the sake of the welfare, benefit, and happiness of many beings, including gods and humans. Your intention in questioning the Tathāgata about this subject is good! It is good! Therefore, Gunākara, listen well and I will describe for you how (Bodhisattvas) are wise with respect to the character of phenomena.

"Gunākara, there are three characteristics of phenomena. What are these three? They are the imputational character, the other-dependent character, and the thoroughly established character.

"Gunākara, what is the imputational character of phenomena?[64] It is that which is imputed as a name or symbol in terms of the own-being or attributes of phenomena in order to subsequently designate any convention whatsoever.

"Gunākara, what is the other-dependent character of phenomena? It is simply the dependent origination of phenomena. It is like this: Because this exists, that arises; because this is produced, that is produced. It ranges from: 'Due to the condition of ignorance, compositional factors (arise),' up to: 'In this way, the whole great assemblage of suffering arises.'[65]

"Gunākara, what is the thoroughly established character of phenomena? It is the suchness of phenomena. Through diligence and through proper mental application, Bodhisattvas establish realization and cultivate realization of (the thoroughly established character). Thus it is what establishes (all the stages) up to unsurpassed, complete, perfect enlightenment.[66]

"Gunākara, for example, the imputational character should be viewed as being like the defects of clouded vision[67] in the eyes of a person with clouded vision. Gunākara; for example, the other-dependent character should be viewed as being like the appearance of the manifestations of clouded vision in that very (person), manifestations which appear as a net of hairs, or as insects, or as sesame seeds; or as a blue manifestation, or a yellow manifestation, or a red manifestation, or a white manifestation.

"Gunākara, for example, the thoroughly established character should be viewed as being like the unerring objective reference, the natural objective reference of the eyes when that person's eyes have become pure and free from the defects of clouded vision.

"Gunakara, for example, when a very clear crystal comes in contact with the color blue, it then appears as a precious gem, such as a sapphire or a mahānīla.[68] Further, by mistaking it for a precious gem such as a sapphire or a mahānīla, sentient beings are deluded.

"When it comes in contact with the color red, it then appears as a precious gem such as a ruby and, by mistaking it for a precious gem such as a ruby, sentient beings are deluded. When it comes in contact with the color green, it then appears as a precious gem such as an emerald and, further, by mistaking it for a precious gem such as an emerald, sentient beings are deluded. When it comes in contact with the color gold, it then appears as gold and, further, by mistaking it for gold, sentient beings are deluded.

"Gunākara, for example, you should see that in the same way as a very clear crystal comes in contact with a color, the other-dependent character comes in contact with the predispositions for conventional designations that are the imputational character. For example, in the same way as a very clear crystal is mistaken for a precious substance such as a sapphire, a mahānīla, a ruby, an emerald, or gold, see how the other-dependent character is apprehended as the imputational character.

"Gunākara, for example, you should see that the otherdependent nature is like that of very clear crystal. For example, a clear crystal is not thoroughly established in permanent, permanent time or in everlasting, everlasting time as having the character of a precious substance like a sapphire, a mahānīla, a ruby, an emerald, or gold, and is without the natures (of such things).

"In the same way, you should see that since the otherdependent character is not thoroughly established in permanent, permanent time, or in everlasting, everlasting time as being the imputational character, and is without its nature, it is the thoroughly established character.

"Gunākara, in dependence upon names that are connected with signs, the imputational character is known. In dependence upon strongly adhering to the other-dependent character as being the imputational character, the otherdependent character is known. In dependence upon absence of strong adherence to the other-dependent character as being the imputational character, the thoroughly established character is known.[69]

"Gunākara, when Bodhisattvas know the imputational character as it really is with respect to the other-dependent character of phenomena, then they know characterless phenomena as they really are.

"Gunākara, when Bodhisattvas know the other-dependent character as it really is, then they know the phenomena of afflicted character as they really are.

"Gunākara, when Bodhisattvas know the thoroughly established character as it really is, then they know the phenomena of purified character as they really are.

"Gunākara, when Bodhisattvas know characterless phenomena as they really are with respect to the other-dependent character, then they completely abandon phenomena of afflicted character. When they have completely abandoned phenomena of afflicted character, they realize phenomena of purified character.

"Therefore, Guçākara, Bodhisattvas know the imputational character of phenomena, the other-dependent character, and the thoroughly established character of phenomena as they really are. Once they know characterlessness, the thoroughly afflicted character, and the purified character as they really are, then they know characterless phenomena as they really are. They completely abandon the phenomena of afflicted character, and when they have completely abandoned phenomena of afflicted character, then they realize phenomena of purified character.

"This is how Bodhisattvas are wise with respect to the character of phenomena. When the Tathāgata designates Bodhisattvas as being wise with respect to the character of phenomena, he designates them as such for this very reason." Then the Bhagavan spoke these verses:

"When one knows characterless phenomena,

one abandons phenomena of afflicted character.

When one abandons phenomena of afflicted character,

one attains phenomena of pure character.

"Heedless beings, overcome by faults and lazy,

do not consider the faults of compounded phenomena.

Weak regarding stable and fluctuating phenomena,

they are objects of compassion."

This completes the sixth chapter of Gunākara

The Questions of Paramār thasamudgatâ

Chapter Seven

Then Bodhisattva Paramārthasamudgata[70] questioned the Bhagavan: "Bhagavan, when I was in seclusion there arose this thought: 'The Bhagavan has spoken in many ways of the own-character of the aggregates and further spoken of their character of production, their character of disintegration, and their abandonment and realization. Just as he has spoken of the aggregates, he has also spoken of the sense spheres, dependent origination, and the sustenances.

"'The Bhagavan has also spoken in many ways of the (own-) character of the (four) truths and further spoken of the realization (of suffering), abandonment (of the source of suffering), actualization (of the cessation of suffering), and meditative cultivation (of the path).

"'The Bhagavan has also spoken in many ways of the owncharacter of the constituents and has further spoken of the various constituents, the manifold constituents, and of their abandonment and realization.

"'The Bhagavan has also spoken in many ways of the owncharacter of the mindful establishments and further spoken of their discordances and antidotes, their meditative cultivation, the production of (the mindful establishments) that have not yet arisen, the abiding of those that have arisen, their nonforgetting, continued arising, increasing, and extending.

"'Just as he spoke of the mindful establishments, he has also spoken of the correct abandonings, the bases of magical abilities, the powers, the forces, and the branches of enlightenment. The Bhagavan has also spoken in many ways of the own-character of the eight branches of the path of the Âryas and further spoken of their discordances and antidotes, their meditative cultivation, the production of those that have not yet arisen, the abiding of those that have arisen, their nonforgetting, continued arising, increasing, and extending.

"'The Bhagavan has also said that all phenomena lack ownbeing, that all phenomena are unproduced, unceasing, quiescent from the start, and naturally in a state of nirvāna.'"

"Then I thought, 'Of what was the Bhagavan thinking when he said, "All phenomena lack own-being; all phenomena are unproduced, unceasing, quiescent from the start, and naturally in a state of nirvāna."

"'Why was the Bhagavan thinking, "All phenomena lack own-being; all phenomena are unproduced, unceasing, quiescent from the start, and naturally in a state of nirvāna?"' I ask the Bhagavan the meaning of this."[71]

The Bhagavan replied to Bodhisattva Paramārthasamudgata: "Paramārthasamudgata, your thought, virtuously arisen, is good! It is good! Paramārthasamudgata, you are involved (in asking) this in order to benefit many beings, to bring happiness to many beings, out of sympathy for the world, and for the sake of the welfare, benefit, and happiness of beings, including gods and humans. Your intention in questioning the Tathāgata about this subject is good! Therefore, Paramārthasamudgata, listen well and I will explain to you what I was thinking when I said: 'All phenomena lack an ownbeing; all phenomena are unproduced, unceasing, quiescent from the start, and naturally in a state of nirvāna.'

"Paramārthasamudgata, thinking of the three types of lack of own-being of phenomena—the lack of own-being in terms of character, the lack of own-being in terms of production, and an ultimate lack of own-being—I taught, 'All phenomena lack own-being.'

"Paramārthasamudgata, what is the lack of own-being in terms of character of phenomena? It is the imputational character. Why is this? The (imputational character) is a character posited as names and symbols, but it does not subsist by way of its own character. Therefore, it is the 'lack of own-being in terms of character'.

"Paramārthasamudgata, what is the lack of own-being in terms of production of phenomena? It is the other-dependent character of phenomena. Why is this? The (other-dependent character) arises through the force of other conditions and not by itself. Therefore, it is the 'lack of own-being in terms of production'.

"Paramārthasamudgata, what is an ultimate lack of ownbeing of phenomena? Phenomena that are dependently originated lack an own-being due to the lack of own-being in terms of production. They also lack own-being due to an ultimate lack of own-being. Why is this? Paramārthasamudgata, I teach that whatever is an object of observation for purification of phenomena is the ultimate.[72] Since the other-dependent character is not an object of observation for purification, it is an 'ultimate lack of own-being'.

"Moreover, Paramārthasamudgata, the thoroughly established character of phenomena is also 'an ultimate lack of own-being'. Why is this? Paramārthasamudgata, that which is the 'selflessness of phenomena' of phenomena is known as their 'lack of own-being'. That is the ultimate. Since the ultimate is distinguished as the lack of own-being of all phenomena, it is an 'ultimate lack of own-being'. "Paramārthasamudgata, for example, you should view lack

of own-being in terms of character as being like a sky-flower.[73] For example, Paramārthasamudgata, you should also view the lack of own-being in terms of production as being like a magical apparition.

"The ultimate lack of own-being should be viewed as being something other than those (first two characters). For example, Paramārthasamudgata, just as (space) is distinguished by being just the lack of own-being of forms in space and as pervading everywhere, in the same way the ultimate lack of own-being is distinguished by being the selflessness of phenomena and should be viewed as all-pervasive and unitary.

"Paramārthasamudgata, thinking of those three types of lack of own-being, I taught, 'All phenomena lack own-being.' "Paramārthasamudgata, thinking of lack of own-being in terms of character, I taught: All phenomena are unproduced, unceasing, quiescent from the start, and naturally in a state of nirvāna.' Why is this?

"Paramārthasamudgata, that which does not exist by way of its own character is not produced. That which is not produced does not cease. That which is not produced and does not cease is quiescent from the start. That which is quiescent from the start is naturally in a state of nirvāna. That which is naturally in a state of nirvāna does not have even the slightest remainder that could pass beyond sorrow. Therefore, thinking of lack of own-being in terms of character, I taught, 'All phenomena are unproduced, unceasing, quiescent from the start, and naturally in a state of nirvāna.'[74]

"Moreover, Paramārthasamudgata, thinking of an ultimate lack of own-being that is distinguished by being the selflessness of phenomena, I taught: 'All phenomena are unproduced, unceasing, quiescent from the start, and naturally in a state of nirvāna.' Why is this?

"An ultimate lack of own-being, distinguished by being the selflessness of phenomena, abides solely in permanent, permanent time and everlasting, everlasting time. That uncompounded reality of phenomena is free from all afflictions. That which is uncompounded, which abides in permanent, permanent time and everlasting, everlasting time due to being this very reality, is uncompounded. Therefore, it is unproduced and unceasing. Because it is free from all afflictions, it is quiescent from the start and is naturally in a state of nirvāna. Therefore, thinking of an ultimate lack of own-being that is distinguished by being the selflessness of phenomena, I taught, 'All phenomena are unproduced, unceasing, quiescent from the start, and naturally in a state of nirvāna.'

"Paramārthasamudgata, I do not designate the three types of lack of own-being because sentient beings in the realms of sentient beings view the own-being of the imputational as distinct (from the other-dependent and the thoroughly established character) in terms of own-being; or because they view the other-dependent and the thoroughly established as distinct in terms of own-being. Superimposing the own-being of the imputational onto the own-being of the other-dependent and the thoroughly established, sentient beings subsequently attribute conventions of the character of the own-being of the imputational to the own-being of the other-dependent and the thoroughly established.

"To the extent that they subsequently attribute such conventions, their minds are infused with conventional designations. Thereafter, because of being bound to conventional designations or due to predispositions toward conventional designations, they strongly adhere to the character of the own-being of the imputational as the own-being of the otherdependent and the thoroughly established.