Difference between revisions of "The solace of surrender"

(Created page with "{{DisplayImages|3926|1153|1259|811|2633}} BUDDHISM ASKS US TO relinquish the domination of the ego and its habits. We can do this by understanding the emptiness of self or ego...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DisplayImages|3926|1153|1259|811|2633}} | {{DisplayImages|3926|1153|1259|811|2633}} | ||

| − | BUDDHISM ASKS US TO relinquish the domination of the ego and its habits. We can do this by understanding the emptiness of self or ego. We can also understand this as the surrender of the ego to a deeper aspect of our nature that is transforming us. We may find that surrendering in this way is unfamiliar, but there are Buddhist practices intended to facilitate exactly this, particularly the practice of prostration. | + | [[BUDDHISM]] ASKS US TO relinquish the {{Wiki|domination}} of the [[ego]] and its [[habits]]. We can do this by [[understanding]] the [[emptiness]] of [[self]] or [[ego]]. We can also understand this as the surrender of the [[ego]] to a deeper aspect of our [[nature]] that is [[transforming]] us. We may find that surrendering in this way is unfamiliar, but there are [[Buddhist practices]] intended to facilitate exactly this, particularly the practice of [[prostration]]. |

| − | I am often asked why prostration—the ritual of bowing, kneeling, or lying face down before an image of the Buddha—is so important in Tibetan Buddhism. Although most schools of Buddhism have this ritual, it is particularly emphasized in the Tibetan tradition. Prostration can seem quaintly medieval; indeed, it has origins in a time when kneeling or lying prostrate on the ground before a king or emperor was expected. The way this has become translated into Buddhist practice therefore needs to be understood more deeply if it is to make sense as a spiritual practice. | + | I am often asked why prostration—the [[ritual]] of bowing, kneeling, or {{Wiki|lying}} face down before an image of the Buddha—is so important in [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. Although most [[schools of Buddhism]] have this [[ritual]], it is particularly emphasized in the [[Tibetan tradition]]. [[Prostration]] can seem quaintly {{Wiki|medieval}}; indeed, it has origins in a [[time]] when kneeling or {{Wiki|lying}} [[prostrate]] on the ground before a [[king]] or [[emperor]] was expected. The way this has become translated into [[Buddhist practice]] therefore needs to be understood more deeply if it is to make [[sense]] as a [[spiritual practice]]. |

| − | Traditional Tibetan teachings on prostration give many examples of its benefits: prostration can purify countless aeons of negative karma; the degree of purification is determined by the area of ground one may cover; the result of practice is rebirth in a beautiful body; and so forth. Personally, I have never found these ideas particularly convincing and have no way of knowing if they are true. I could see how the practice could counter pride, but always felt there must be more to it psychologically. When we understand that the figure, often a deity, to which we prostrate ourselves is an image of our totality—or, to use Jung’s language, an image of the Self—then we are performing a practice that involves the ego’s surrender to the Self. If we translate this into Buddhist understanding, the ego is honoring the more profound wisdom of our Buddha-nature, manifest in the deity. | + | [[Traditional]] [[Tibetan]] teachings on [[prostration]] give many examples of its benefits: [[prostration]] can {{Wiki|purify}} countless [[aeons]] of [[negative karma]]; the [[degree]] of [[purification]] is determined by the area of ground one may cover; the result of practice is [[rebirth]] in a beautiful [[body]]; and so forth. Personally, I have never found these [[ideas]] particularly convincing and have no way of [[knowing]] if they are true. I could see how the practice could counter [[pride]], but always felt there must be more to it {{Wiki|psychologically}}. When we understand that the figure, often a [[deity]], to which we [[prostrate]] ourselves is an image of our totality—or, to use Jung’s [[language]], an image of the Self—then we are performing a practice that involves the ego’s surrender to the [[Self]]. If we translate this into [[Buddhist]] [[understanding]], the [[ego]] is honoring the more [[profound wisdom]] of our [[Buddha-nature]], [[manifest]] in the [[deity]]. |

| − | Having performed around two hundred thousand prostrations in India between 1980 and 1985, I became very aware of the cleansing or purification power of the practice. Even just treated as a repetitive physical exercise, prostrations release huge amounts of emotional toxins held in the body. During periods of intense prostrations in Bodh Gaya beside the Maha Bodhi Temple, I experienced an extraordinary shift in the energetic nature of my body. Sometimes I found myself in agony, at others, ecstatic. What became particularly apparent as I continued this practice, however, was a powerful feeling of surrender. I sensed a deep shift in orientation as my Buddha-nature became the center of my journey, the root of meaning and direction. I was gradually giving up some level of self-will in order to align with a deeper sense of what must unfold. It has often surprised me that in the process of surrender what I give up is fear and struggle. A kind of strength comes from truly giving up. Something changes when I genuinely let go and ask for help. The challenge is maintaining this openness, rather than grasping at solid forms or quick solutions to feel safe. It’s not that I give up personal responsibility, believing that some external entity is going to rescue me. Rather, I realize that if I truly listen to the innate wisdom of my Buddha-nature, it will guide me. | + | Having performed around two hundred thousand [[prostrations]] in [[India]] between 1980 and 1985, I became very {{Wiki|aware}} of the cleansing or [[purification]] power of the practice. Even just treated as a repetitive [[physical]] exercise, [[prostrations]] release huge amounts of [[emotional]] toxins held in the [[body]]. During periods of intense [[prostrations]] in [[Bodh Gaya]] beside the [[Maha Bodhi Temple]], I [[experienced]] an [[extraordinary]] shift in the energetic [[nature]] of my [[body]]. Sometimes I found myself in agony, at others, {{Wiki|ecstatic}}. What became particularly apparent as I continued this practice, however, was a powerful [[feeling]] of surrender. I [[sensed]] a deep shift in orientation as my [[Buddha-nature]] became the center of my journey, the [[root]] of meaning and [[direction]]. I was gradually giving up some level of self-will in order to align with a deeper [[sense]] of what must unfold. It has often surprised me that in the process of surrender what I give up is {{Wiki|fear}} and struggle. A kind of strength comes from truly giving up. Something changes when I genuinely let go and ask for help. The challenge is maintaining this [[openness]], rather than [[grasping]] at solid [[forms]] or quick solutions to [[feel]] safe. It’s not that I give up personal {{Wiki|responsibility}}, believing that some external [[entity]] is going to rescue me. Rather, I realize that if I truly listen to the innate [[wisdom]] of my [[Buddha-nature]], it will [[guide]] me. “[[Trust]] your inner knowledge-wisdom,” my [[teacher]] [[Lama Thubten Yeshe]] used to say. |

| − | As we learn to surrender, we may discover that we’re very afraid to make such a deep psychological transition. In what do we trust if we give up control? To support our journey, we can project our surrender onto an outer person in the form of a guru. Many Tibetan Buddhist texts put great emphasis on the guru, “to whose lotus feet we prostrate ourselves,” as the root of the path and the source of realization. As Westerners we often have a certain ambivalence about this; we worry about whether or not the guru is trustworthy. There are times when it is fundamentally inappropriate or even hazardous to give so much power away. But if we understand the guru to be a projection of our own innate Buddha-nature, this relationship makes more sense. | + | As we learn to surrender, we may discover that we’re very afraid to make such a deep [[psychological]] transition. In what do we [[trust]] if we give up control? To support our journey, we can project our surrender onto an outer [[person]] in the [[form]] of a [[guru]]. Many [[Tibetan Buddhist]] texts put great {{Wiki|emphasis}} on the [[guru]], “to whose [[lotus]] feet we [[prostrate]] ourselves,” as the [[root]] of the [[path]] and the source of [[realization]]. As Westerners we often have a certain ambivalence about this; we {{Wiki|worry}} about whether or not the [[guru]] is trustworthy. There are times when it is fundamentally inappropriate or even hazardous to give so much power away. But if we understand the [[guru]] to be a projection of our own innate [[Buddha-nature]], this relationship makes more [[sense]]. |

| − | AS WE SURRENDER, we offer the whole of our life to the process of awakening. “In order to benefit sentient beings,” writes Pabongka Rinpoche in the Heruka Sadhana, “I offer myself immediately to all the Buddhas.” We offer ourselves as a vehicle for our Buddha-nature to manifest in the world for the welfare of others. We allow ourselves to be transformed. With this heartfelt attitude, one prostration performed at the right moment can touch us as deeply as one hundred thousand done without such commitment. | + | AS WE SURRENDER, we offer the whole of our [[life]] to the process of [[awakening]]. “In order to [[benefit]] [[sentient beings]],” writes [[Pabongka Rinpoche]] in the [[Heruka]] [[Sadhana]], “I offer myself immediately to all the [[Buddhas]].” We offer ourselves as a [[vehicle]] for our [[Buddha-nature]] to [[manifest]] in the [[world]] for the {{Wiki|welfare}} of others. We allow ourselves to be [[transformed]]. With this heartfelt [[attitude]], one [[prostration]] performed at the right moment can {{Wiki|touch}} us as deeply as one hundred thousand done without such commitment. |

| − | I have found that this process of surrender can profoundly affect the level of anxiety in our daily lives. For someone who is self-employed (like me), times when work is scarce can be very challenging. Fearing disaster, I can go into an insecure, anxious state. Insecurity makes many of us work so hard that we become stressed and even ill. It is then very hard to let go and trust that we will be okay. The transition is uncomfortable, and instead of allowing change to unfold we often stay in a safety zone that becomes increasingly unhealthy. But I have found that if I can surrender to the process and trust that something needs to change, my anxiety declines. I can create an inner space for something new to unfold rather than lock into a pattern. At these times I find myself offering my life up with the thought “May my life be taken where it is most beneficial to go.” | + | I have found that this process of surrender can profoundly affect the level of [[anxiety]] in our daily [[lives]]. For someone who is self-employed (like me), times when work is scarce can be very challenging. Fearing {{Wiki|disaster}}, I can go into an insecure, anxious state. Insecurity makes many of us work so hard that we become stressed and even ill. It is then very hard to let go and [[trust]] that we will be okay. The transition is uncomfortable, and instead of allowing change to unfold we often stay in a safety zone that becomes increasingly [[unhealthy]]. But I have found that if I can surrender to the process and [[trust]] that something needs to change, my [[anxiety]] declines. I can create an [[inner space]] for something new to unfold rather than lock into a pattern. At these times I find myself [[offering]] my [[life]] up with the [[thought]] “May my [[life]] be taken where it is most beneficial to go.” |

| − | A paradox inherent in this process is expressed by the curious Middle Eastern proverb | + | A [[paradox]] [[inherent]] in this process is expressed by the curious Middle Eastern proverb “[[Trust]] in [[God]] but tether your {{Wiki|camel}}.” While we need to let go and give up on one level, we must be practical and retain a [[sense]] of active participation in and {{Wiki|responsibility}} for the process. We do not simply drift into a kind of [[formless]] [[abandonment]] of the practicalities of [[life]]. This does not mean falling back into the [[Wikipedia:Habit (psychology)|habit]] of trying to compulsively organize everything so that we [[feel]] in control. We must walk a fine line between surrender and engagement. As we individuate, we learn to remain open to the [[nature]] of uncertainty in the journey, allowing ourselves to fearlessly unfold. At the same [[time]], our active participation in the process functions as a kind of {{Wiki|dialogue}} between the [[ego]] and our [[Buddha-nature]]. We still pay the bills, do the washing up, and take the kids to school. We may not know where this journey will take us, but we can [[trust]] that as we fully engage in the deeper undercurrent of unfolding, [[life]] will become ever more fulfilling. |

| − | Rob Preece has been a practicing Buddhist since 1973, principally within the Tibetan tradition, and has been working as a psychotherapist since 1987. He is the author of The Wisdom of Imperfection and The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra (both from Snow Lion Publications). | + | Rob Preece has been a practicing [[Buddhist]] since 1973, principally within the [[Tibetan tradition]], and has been working as a psychotherapist since 1987. He is the author of The [[Wisdom]] of Imperfection and The {{Wiki|Psychology}} of [[Buddhist Tantra]] (both from [[Snow Lion Publications]]). |

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://sgforums.com/forums/1728/topics/416499 sgforums.com] | [http://sgforums.com/forums/1728/topics/416499 sgforums.com] | ||

[[Category:Buddhist Practices]] | [[Category:Buddhist Practices]] | ||

Revision as of 17:43, 4 July 2014

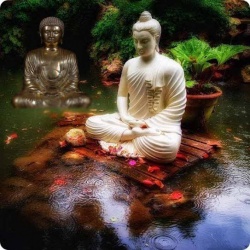

BUDDHISM ASKS US TO relinquish the domination of the ego and its habits. We can do this by understanding the emptiness of self or ego. We can also understand this as the surrender of the ego to a deeper aspect of our nature that is transforming us. We may find that surrendering in this way is unfamiliar, but there are Buddhist practices intended to facilitate exactly this, particularly the practice of prostration.

I am often asked why prostration—the ritual of bowing, kneeling, or lying face down before an image of the Buddha—is so important in Tibetan Buddhism. Although most schools of Buddhism have this ritual, it is particularly emphasized in the Tibetan tradition. Prostration can seem quaintly medieval; indeed, it has origins in a time when kneeling or lying prostrate on the ground before a king or emperor was expected. The way this has become translated into Buddhist practice therefore needs to be understood more deeply if it is to make sense as a spiritual practice.

Traditional Tibetan teachings on prostration give many examples of its benefits: prostration can purify countless aeons of negative karma; the degree of purification is determined by the area of ground one may cover; the result of practice is rebirth in a beautiful body; and so forth. Personally, I have never found these ideas particularly convincing and have no way of knowing if they are true. I could see how the practice could counter pride, but always felt there must be more to it psychologically. When we understand that the figure, often a deity, to which we prostrate ourselves is an image of our totality—or, to use Jung’s language, an image of the Self—then we are performing a practice that involves the ego’s surrender to the Self. If we translate this into Buddhist understanding, the ego is honoring the more profound wisdom of our Buddha-nature, manifest in the deity.

Having performed around two hundred thousand prostrations in India between 1980 and 1985, I became very aware of the cleansing or purification power of the practice. Even just treated as a repetitive physical exercise, prostrations release huge amounts of emotional toxins held in the body. During periods of intense prostrations in Bodh Gaya beside the Maha Bodhi Temple, I experienced an extraordinary shift in the energetic nature of my body. Sometimes I found myself in agony, at others, ecstatic. What became particularly apparent as I continued this practice, however, was a powerful feeling of surrender. I sensed a deep shift in orientation as my Buddha-nature became the center of my journey, the root of meaning and direction. I was gradually giving up some level of self-will in order to align with a deeper sense of what must unfold. It has often surprised me that in the process of surrender what I give up is fear and struggle. A kind of strength comes from truly giving up. Something changes when I genuinely let go and ask for help. The challenge is maintaining this openness, rather than grasping at solid forms or quick solutions to feel safe. It’s not that I give up personal responsibility, believing that some external entity is going to rescue me. Rather, I realize that if I truly listen to the innate wisdom of my Buddha-nature, it will guide me. “Trust your inner knowledge-wisdom,” my teacher Lama Thubten Yeshe used to say.

As we learn to surrender, we may discover that we’re very afraid to make such a deep psychological transition. In what do we trust if we give up control? To support our journey, we can project our surrender onto an outer person in the form of a guru. Many Tibetan Buddhist texts put great emphasis on the guru, “to whose lotus feet we prostrate ourselves,” as the root of the path and the source of realization. As Westerners we often have a certain ambivalence about this; we worry about whether or not the guru is trustworthy. There are times when it is fundamentally inappropriate or even hazardous to give so much power away. But if we understand the guru to be a projection of our own innate Buddha-nature, this relationship makes more sense.

AS WE SURRENDER, we offer the whole of our life to the process of awakening. “In order to benefit sentient beings,” writes Pabongka Rinpoche in the Heruka Sadhana, “I offer myself immediately to all the Buddhas.” We offer ourselves as a vehicle for our Buddha-nature to manifest in the world for the welfare of others. We allow ourselves to be transformed. With this heartfelt attitude, one prostration performed at the right moment can touch us as deeply as one hundred thousand done without such commitment.

I have found that this process of surrender can profoundly affect the level of anxiety in our daily lives. For someone who is self-employed (like me), times when work is scarce can be very challenging. Fearing disaster, I can go into an insecure, anxious state. Insecurity makes many of us work so hard that we become stressed and even ill. It is then very hard to let go and trust that we will be okay. The transition is uncomfortable, and instead of allowing change to unfold we often stay in a safety zone that becomes increasingly unhealthy. But I have found that if I can surrender to the process and trust that something needs to change, my anxiety declines. I can create an inner space for something new to unfold rather than lock into a pattern. At these times I find myself offering my life up with the thought “May my life be taken where it is most beneficial to go.”

A paradox inherent in this process is expressed by the curious Middle Eastern proverb “Trust in God but tether your camel.” While we need to let go and give up on one level, we must be practical and retain a sense of active participation in and responsibility for the process. We do not simply drift into a kind of formless abandonment of the practicalities of life. This does not mean falling back into the habit of trying to compulsively organize everything so that we feel in control. We must walk a fine line between surrender and engagement. As we individuate, we learn to remain open to the nature of uncertainty in the journey, allowing ourselves to fearlessly unfold. At the same time, our active participation in the process functions as a kind of dialogue between the ego and our Buddha-nature. We still pay the bills, do the washing up, and take the kids to school. We may not know where this journey will take us, but we can trust that as we fully engage in the deeper undercurrent of unfolding, life will become ever more fulfilling.

Rob Preece has been a practicing Buddhist since 1973, principally within the Tibetan tradition, and has been working as a psychotherapist since 1987. He is the author of The Wisdom of Imperfection and The Psychology of Buddhist Tantra (both from Snow Lion Publications).