Difference between revisions of "Buddhism more scientific than modern science"

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

[[Ordinary people]] know so little about [[science]] that they can hardly even understand the jargon. Yet, if they read in a newspaper or magazine "a [[scientist]] says that?", then they automatically take it to be true. | [[Ordinary people]] know so little about [[science]] that they can hardly even understand the jargon. Yet, if they read in a newspaper or magazine "a [[scientist]] says that?", then they automatically take it to be true. | ||

| − | Compare this to our {{Wiki|reaction}} when we read in the same journal "a politician says that?"! Why do [[scientists]] have such unchallenged credibility? Perhaps it is because the [[language]] and [[ritual]] of [[science]] has become so far removed from the common [[people]], that [[scientists]] have become today's revered and [[mystical]] priesthood. Dressed in their {{Wiki|ceremonial}} white lab coats, [[chanting]] incomprehensible mumbo jumbo about multi-dimensional fractal parallel [[universes]], and performing [[magical]] [[rituals]] that transubstantiate metal and plastic into TV's and computers, these {{Wiki|modern}} day alchemists are so awesome we'll believe anything they say. Elitist [[science]], as once was the Pope, is now infallible. | + | Compare this to our {{Wiki|reaction}} when we read in the same journal "a politician says that?"! Why do [[scientists]] have such unchallenged credibility? Perhaps it is because the [[language]] and [[ritual]] of [[science]] has become so far removed from the common [[people]], that [[scientists]] have become today's revered and [[mystical]] priesthood. Dressed in their {{Wiki|ceremonial}} white lab coats, [[chanting]] incomprehensible mumbo jumbo about multi-dimensional fractal parallel [[universes]], and performing [[magical]] [[rituals]] that transubstantiate metal and plastic into TV's and computers, these {{Wiki|modern}} day alchemists are so awesome we'll believe anything they say. Elitist [[science]], as once was the [[Pope]], is now infallible. |

Some know better. Much of what I learnt 30 years ago has now been proved wrong. There are, fortunately, many [[scientists]] with [[integrity]] and {{Wiki|humility}} who affirm that [[science]] is, at best, a work still in progress. They know that [[science]] can only suggest a [[truth]], but can never claim a [[truth]]. I was once told by a [[Buddhist]] G.P. that, on his first day at a {{Wiki|medical}} school in {{Wiki|Sydney}}, the famous {{Wiki|Professor}}, head of the {{Wiki|Medical}} School, began his welcoming address by stating "Half of what we are going to teach you in the next few years is wrong. Our problem is that we do not know which half it is!" Those were the words of a {{Wiki|real}} [[scientist]]. | Some know better. Much of what I learnt 30 years ago has now been proved wrong. There are, fortunately, many [[scientists]] with [[integrity]] and {{Wiki|humility}} who affirm that [[science]] is, at best, a work still in progress. They know that [[science]] can only suggest a [[truth]], but can never claim a [[truth]]. I was once told by a [[Buddhist]] G.P. that, on his first day at a {{Wiki|medical}} school in {{Wiki|Sydney}}, the famous {{Wiki|Professor}}, head of the {{Wiki|Medical}} School, began his welcoming address by stating "Half of what we are going to teach you in the next few years is wrong. Our problem is that we do not know which half it is!" Those were the words of a {{Wiki|real}} [[scientist]]. | ||

| − | [[Buddhism]] is more [[scientific]] than {{Wiki|modern}} [[science]]. Like [[science]], [[Buddhism]] is based on verifiable [[cause-and-effect]] relationships. But unlike [[science]], [[Buddhism]] challenges with thoroughness every [[belief]]. The famous [[Kalama Sutta]] of [[Buddhism]] states that one cannot believe fully in "what one is [[taught]], [[tradition]], hearsay, [[scripture]], [[logic]], {{Wiki|inference}}, [[appearance]], agreement with established opinion, the seeming competence of a [[teacher]], or even in one's [[own]] [[teacher]]". How many [[scientists]] are as rigorous in their [[thinking]] as this? [[Buddhism]] challenges everything, including [[logic]]. | + | [[Buddhism]] is more [[scientific]] than {{Wiki|modern}} [[science]]. Like [[science]], [[Buddhism]] is based on verifiable [[cause-and-effect]] relationships. But unlike [[science]], [[Buddhism]] challenges with thoroughness every [[belief]]. The famous [[Kalama Sutta]] of [[Buddhism]] states that one cannot believe fully in "what one is [[taught]], [[tradition]], hearsay, [[scripture]], [[logic]], {{Wiki|inference}}, [[appearance]], agreement with established opinion, the seeming competence of a [[teacher]], or even in one's [[own]] [[teacher]]". How many [[scientists]] are as rigorous in their [[thinking]] as this? [[Buddhism]] challenges everything, [[including]] [[logic]]. |

| − | It is worth noting that {{Wiki|Quantum Theory}} appeared quite illogical, even to such great [[scientists]] as {{Wiki|Einstein}}, when it was first proposed. It is yet to be disproved. [[Logic]] is only as reliable as the {{Wiki|assumptions}} on which it is based. [[Buddhism]] trusts only clear and [[objective]] [[experience]]. | + | It is worth noting that {{Wiki|Quantum Theory}} appeared quite [[illogical]], even to such great [[scientists]] as {{Wiki|Einstein}}, when it was first proposed. It is yet to be disproved. [[Logic]] is only as reliable as the {{Wiki|assumptions}} on which it is based. [[Buddhism]] trusts only clear and [[objective]] [[experience]]. |

Clear [[experience]] occurs when one's [[measuring]] instruments, one's [[senses]], are bright and undisturbed. In [[Buddhism]], this happens when the [[hindrances]] of sloth-and-torpor and restlessness-and-remorse are both overcome. [[Objective]] [[experience]] is that which is free from all bias. In [[Buddhism]], the three types of bias are [[desire]], [[ill will]] and [[sceptical doubt]]. [[Desire]] makes one see only what one wants to see, it bends the [[truth]] to fit one's preferences. [[Ill will]] makes one [[blind]] to whatever is {{Wiki|disturbing}} or disconcerting to one's [[views]] and it distorts the [[truth]] by {{Wiki|denial}}. [[Sceptical doubt]] stubbornly refuses to accept those [[truths]], like [[rebirth]], that are plainly valid but which fall outside of one's comforting worldview. In summary, clear and [[objective]] [[experience]] only happens when the [[Buddhist]] '[[Five Hindrances]]' have been overcome. Only then can one [[trust]] the {{Wiki|data}} arriving through one's [[senses]]. | Clear [[experience]] occurs when one's [[measuring]] instruments, one's [[senses]], are bright and undisturbed. In [[Buddhism]], this happens when the [[hindrances]] of sloth-and-torpor and restlessness-and-remorse are both overcome. [[Objective]] [[experience]] is that which is free from all bias. In [[Buddhism]], the three types of bias are [[desire]], [[ill will]] and [[sceptical doubt]]. [[Desire]] makes one see only what one wants to see, it bends the [[truth]] to fit one's preferences. [[Ill will]] makes one [[blind]] to whatever is {{Wiki|disturbing}} or disconcerting to one's [[views]] and it distorts the [[truth]] by {{Wiki|denial}}. [[Sceptical doubt]] stubbornly refuses to accept those [[truths]], like [[rebirth]], that are plainly valid but which fall outside of one's comforting worldview. In summary, clear and [[objective]] [[experience]] only happens when the [[Buddhist]] '[[Five Hindrances]]' have been overcome. Only then can one [[trust]] the {{Wiki|data}} arriving through one's [[senses]]. | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

Because [[scientists]] are not free of these [[five hindrances]], they are rarely clear and [[objective]]. It is common, for example, for [[scientists]] to ignore annoying {{Wiki|data}}, which do not fit their cherished theories, or else confine such {{Wiki|evidence}} to oblivion by filing it away as an 'anomaly'. Even most [[Buddhists]] aren't clear and [[objective]]. One has to have recent [[experience]] of [[Jhana]] to effectively put aside these [[five hindrances]] (according to the [[Nalakapana]] [[Sutta]], [[Majjhima]] No. 68). So only accomplished [[meditators]] can claim to be {{Wiki|real}} [[scientists]], that is, clear and [[objective]]. | Because [[scientists]] are not free of these [[five hindrances]], they are rarely clear and [[objective]]. It is common, for example, for [[scientists]] to ignore annoying {{Wiki|data}}, which do not fit their cherished theories, or else confine such {{Wiki|evidence}} to oblivion by filing it away as an 'anomaly'. Even most [[Buddhists]] aren't clear and [[objective]]. One has to have recent [[experience]] of [[Jhana]] to effectively put aside these [[five hindrances]] (according to the [[Nalakapana]] [[Sutta]], [[Majjhima]] No. 68). So only accomplished [[meditators]] can claim to be {{Wiki|real}} [[scientists]], that is, clear and [[objective]]. | ||

| − | [[Science]] claims to rely not only on clear and [[objective]] observation, but also on measurement. But what is measurement in [[science]]? To [[measure]] something, according to the [[pure]] [[science]] of {{Wiki|Quantum Theory}}, is to collapse the Schroedinger Wave Equation through an act of observation. Moreover, the "un-collapsed" [[form]] of the Schroedinger Wave Equation, that is before any measurement is made, is, perhaps, science's most {{Wiki|perfect}} description of the [[world]]. That description is weird! [[Reality]], according to [[pure]] [[science]], does not consist of well ordered {{Wiki|matter}} with precise massed, energies and positions in [[space]], all just waiting to be measured. [[Reality]] is the broadest of smudges of all possibilities, only some being more probable than others. Even basic 'measurable' qualities as 'alive' or '[[dead]]' have been demonstrated by [[science]] to be invalid sometimes. In the notorious '[[Wikipedia:Erwin Schrödinger|Schroedinger's]] {{Wiki|Cat}}' [[thought]] experiment, Prof. [[Wikipedia:Erwin Schrödinger|Schroedinger's]] {{Wiki|cat}} was ingeniously placed in a {{Wiki|real}} situation where it was neither [[dead]] nor alive, where such measurements became meaningless. [[Reality]], according to {{Wiki|Quantum Theory}}, is [[beyond]] measurements. [[Measuring]] disturbs [[reality]], it never describes it perfectly. It was [[Wikipedia:Werner Heisenberg|Heisenberg's]] famous '{{Wiki|Uncertainty Principle}}' that showed the inevitable error between the {{Wiki|real}} {{Wiki|Quantum}} [[world]] and the measured [[world]] of pseudo-science. | + | [[Science]] claims to rely not only on clear and [[objective]] observation, but also on measurement. But what is measurement in [[science]]? To [[measure]] something, according to the [[pure]] [[science]] of {{Wiki|Quantum Theory}}, is to collapse the [[Schroedinger]] Wave Equation through an act of observation. Moreover, the "un-collapsed" [[form]] of the [[Schroedinger]] Wave Equation, that is before any measurement is made, is, perhaps, science's most {{Wiki|perfect}} description of the [[world]]. That description is weird! [[Reality]], according to [[pure]] [[science]], does not consist of well ordered {{Wiki|matter}} with precise massed, energies and positions in [[space]], all just waiting to be measured. [[Reality]] is the broadest of smudges of all possibilities, only some being more probable than others. Even basic 'measurable' qualities as 'alive' or '[[dead]]' have been demonstrated by [[science]] to be invalid sometimes. In the notorious '[[Wikipedia:Erwin Schrödinger|Schroedinger's]] {{Wiki|Cat}}' [[thought]] experiment, Prof. [[Wikipedia:Erwin Schrödinger|Schroedinger's]] {{Wiki|cat}} was ingeniously placed in a {{Wiki|real}} situation where it was neither [[dead]] nor alive, where such measurements became meaningless. [[Reality]], according to {{Wiki|Quantum Theory}}, is [[beyond]] measurements. [[Measuring]] disturbs [[reality]], it never describes it perfectly. It was [[Wikipedia:Werner Heisenberg|Heisenberg's]] famous '{{Wiki|Uncertainty Principle}}' that showed the inevitable error between the {{Wiki|real}} {{Wiki|Quantum}} [[world]] and the measured [[world]] of pseudo-science. |

Anyway, how can anyone [[measure]] the measurer, the [[mind]]? At a recent seminar on [[Science]] and [[Religion]], at which I was a speaker, a {{Wiki|Catholic}} in the audience bravely announced that whenever she looks through a {{Wiki|telescope}} at the {{Wiki|stars}}, she [[feels]] uncomfortable because her [[religion]] is threatened. I commented that whenever a [[scientist]] looks the other way round through a {{Wiki|telescope}}, to observe the one who is watching, then they [[feel]] uncomfortable because their [[science]] is threatened by what is doing the [[seeing]]! So what is doing the [[seeing]], what is this [[mind]] that eludes {{Wiki|modern}} [[science]]? | Anyway, how can anyone [[measure]] the measurer, the [[mind]]? At a recent seminar on [[Science]] and [[Religion]], at which I was a speaker, a {{Wiki|Catholic}} in the audience bravely announced that whenever she looks through a {{Wiki|telescope}} at the {{Wiki|stars}}, she [[feels]] uncomfortable because her [[religion]] is threatened. I commented that whenever a [[scientist]] looks the other way round through a {{Wiki|telescope}}, to observe the one who is watching, then they [[feel]] uncomfortable because their [[science]] is threatened by what is doing the [[seeing]]! So what is doing the [[seeing]], what is this [[mind]] that eludes {{Wiki|modern}} [[science]]? | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

However, she was not quite right. The [[mind]] can see everything that one's [[eye]] can see, and it can also [[imagine]] so much more. It can also hear, {{Wiki|smell}}, {{Wiki|taste}} and {{Wiki|touch}}, as well as think. In fact, everything that can be known can fit into the [[mind]]. Therefore, the [[mind]] must be the biggest thing in the [[world]]. Science's mistake is obvious now. The [[mind]] is not in the {{Wiki|brain}}, nor in the [[body]]. The {{Wiki|brain}}, the [[body]] and the rest of the [[world]], are in the [[mind]]! | However, she was not quite right. The [[mind]] can see everything that one's [[eye]] can see, and it can also [[imagine]] so much more. It can also hear, {{Wiki|smell}}, {{Wiki|taste}} and {{Wiki|touch}}, as well as think. In fact, everything that can be known can fit into the [[mind]]. Therefore, the [[mind]] must be the biggest thing in the [[world]]. Science's mistake is obvious now. The [[mind]] is not in the {{Wiki|brain}}, nor in the [[body]]. The {{Wiki|brain}}, the [[body]] and the rest of the [[world]], are in the [[mind]]! | ||

| − | [[Mind]] is the sixth [[sense]] in [[Buddhism]], it is that which encompasses the [[five senses]] of [[sight]], hearing, {{Wiki|smell}}, {{Wiki|taste}} and {{Wiki|touch}}, and {{Wiki|transcends}} them with its [[own]] domain. It corresponds loosely to Aristotle's "{{Wiki|common sense}}" that is {{Wiki|distinct}} from the [[five senses]]. Indeed, {{Wiki|ancient Greek}} [[philosophy]], from where [[science]] is said to have its origins, [[taught]] [[six senses]] just like [[Buddhism]]. Somewhere along the historical journey of {{Wiki|European}} [[thinking]], they lost their [[mind]]! Or, as {{Wiki|Aristotle}} would put it, they somehow discarded their "{{Wiki|common sense}}"! And thus we got [[science]]. We got {{Wiki|materialism}} without any [[heart]]. One can accurately say that [[Buddhism]] is a [[science]] that has kept its [[heart]], and which hasn't lost its [[mind]]! | + | [[Mind]] is the sixth [[sense]] in [[Buddhism]], it is that which encompasses the [[five senses]] of [[sight]], hearing, {{Wiki|smell}}, {{Wiki|taste}} and {{Wiki|touch}}, and {{Wiki|transcends}} them with its [[own]] domain. It corresponds loosely to [[Aristotle's]] "{{Wiki|common sense}}" that is {{Wiki|distinct}} from the [[five senses]]. Indeed, {{Wiki|ancient Greek}} [[philosophy]], from where [[science]] is said to have its origins, [[taught]] [[six senses]] just like [[Buddhism]]. Somewhere along the historical journey of {{Wiki|European}} [[thinking]], they lost their [[mind]]! Or, as {{Wiki|Aristotle}} would put it, they somehow discarded their "{{Wiki|common sense}}"! And thus we got [[science]]. We got {{Wiki|materialism}} without any [[heart]]. One can accurately say that [[Buddhism]] is a [[science]] that has kept its [[heart]], and which hasn't lost its [[mind]]! |

Thus [[Buddhism]] is not a [[belief]] system. It is a [[science]] founded on [[objective]] observation, i.e. [[meditation]], ever careful not to disturb the [[reality]] through imposing artificial measurements, and it is evidently repeatable. | Thus [[Buddhism]] is not a [[belief]] system. It is a [[science]] founded on [[objective]] observation, i.e. [[meditation]], ever careful not to disturb the [[reality]] through imposing artificial measurements, and it is evidently repeatable. | ||

Revision as of 17:33, 30 November 2023

Ven. Ajahn Brahmavamso reflects on Buddhism’s enduring significance

I used to be a scientist. I did Theoretical Physics at Cambridge University, hanging out in the same building as the later-to-be-famous Professor Stephen Hawking. I became disillusioned with such science when, as an insider, I saw how dogmatic some scientists could be.

A dogma, according to the dictionary, is an arrogant declaration of an opinion. This was a fitting description of the science that I saw in the labs of Cambridge. Science had lost its sense of humility. Egotistical opinion prevailed over the impartial search for Truth. My favourite aphorism from that time was: "The eminence of a great scientist, is measured by the length of time that they OBSTRUCT PROGRESS in their field"!

To understand real science, one can go back to one of its founding fathers, the English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561 - 1628). He established the framework on which science was to progress, namely "the greater force of the negative instance". This meant that, having proposed a theory to explain some natural phenomenon, then one should try one's best to disprove it! One should test the theory with challenging experiments.

One must put it on trial with rigorous argument. When a flaw appears in the theory, only then does science advance. A new discovery has been made enabling the theory to be adjusted and refined. This fundamental and original methodology of science understood that it is impossible to prove anything with absolute certainty. One can only disprove with absolute certainty.

Some misguided scientists maintain the theory that there is no rebirth, that this stream of consciousness is incapable of returning to a successive human existence. All one needs to disprove this theory, according to science, is to find one instance of rebirth, just one! Professor Ian Stevenson, as some of you would know, has already demonstrated many instances of rebirth. The theory of no rebirth has been disproved. Rebirth is now a scientific fact!

Ordinary people know so little about science that they can hardly even understand the jargon. Yet, if they read in a newspaper or magazine "a scientist says that?", then they automatically take it to be true.

Compare this to our reaction when we read in the same journal "a politician says that?"! Why do scientists have such unchallenged credibility? Perhaps it is because the language and ritual of science has become so far removed from the common people, that scientists have become today's revered and mystical priesthood. Dressed in their ceremonial white lab coats, chanting incomprehensible mumbo jumbo about multi-dimensional fractal parallel universes, and performing magical rituals that transubstantiate metal and plastic into TV's and computers, these modern day alchemists are so awesome we'll believe anything they say. Elitist science, as once was the Pope, is now infallible.

Some know better. Much of what I learnt 30 years ago has now been proved wrong. There are, fortunately, many scientists with integrity and humility who affirm that science is, at best, a work still in progress. They know that science can only suggest a truth, but can never claim a truth. I was once told by a Buddhist G.P. that, on his first day at a medical school in Sydney, the famous Professor, head of the Medical School, began his welcoming address by stating "Half of what we are going to teach you in the next few years is wrong. Our problem is that we do not know which half it is!" Those were the words of a real scientist.

Buddhism is more scientific than modern science. Like science, Buddhism is based on verifiable cause-and-effect relationships. But unlike science, Buddhism challenges with thoroughness every belief. The famous Kalama Sutta of Buddhism states that one cannot believe fully in "what one is taught, tradition, hearsay, scripture, logic, inference, appearance, agreement with established opinion, the seeming competence of a teacher, or even in one's own teacher". How many scientists are as rigorous in their thinking as this? Buddhism challenges everything, including logic.

It is worth noting that Quantum Theory appeared quite illogical, even to such great scientists as Einstein, when it was first proposed. It is yet to be disproved. Logic is only as reliable as the assumptions on which it is based. Buddhism trusts only clear and objective experience.

Clear experience occurs when one's measuring instruments, one's senses, are bright and undisturbed. In Buddhism, this happens when the hindrances of sloth-and-torpor and restlessness-and-remorse are both overcome. Objective experience is that which is free from all bias. In Buddhism, the three types of bias are desire, ill will and sceptical doubt. Desire makes one see only what one wants to see, it bends the truth to fit one's preferences. Ill will makes one blind to whatever is disturbing or disconcerting to one's views and it distorts the truth by denial. Sceptical doubt stubbornly refuses to accept those truths, like rebirth, that are plainly valid but which fall outside of one's comforting worldview. In summary, clear and objective experience only happens when the Buddhist 'Five Hindrances' have been overcome. Only then can one trust the data arriving through one's senses.

Because scientists are not free of these five hindrances, they are rarely clear and objective. It is common, for example, for scientists to ignore annoying data, which do not fit their cherished theories, or else confine such evidence to oblivion by filing it away as an 'anomaly'. Even most Buddhists aren't clear and objective. One has to have recent experience of Jhana to effectively put aside these five hindrances (according to the Nalakapana Sutta, Majjhima No. 68). So only accomplished meditators can claim to be real scientists, that is, clear and objective.

Science claims to rely not only on clear and objective observation, but also on measurement. But what is measurement in science? To measure something, according to the pure science of Quantum Theory, is to collapse the Schroedinger Wave Equation through an act of observation. Moreover, the "un-collapsed" form of the Schroedinger Wave Equation, that is before any measurement is made, is, perhaps, science's most perfect description of the world. That description is weird! Reality, according to pure science, does not consist of well ordered matter with precise massed, energies and positions in space, all just waiting to be measured. Reality is the broadest of smudges of all possibilities, only some being more probable than others. Even basic 'measurable' qualities as 'alive' or 'dead' have been demonstrated by science to be invalid sometimes. In the notorious 'Schroedinger's Cat' thought experiment, Prof. Schroedinger's cat was ingeniously placed in a real situation where it was neither dead nor alive, where such measurements became meaningless. Reality, according to Quantum Theory, is beyond measurements. Measuring disturbs reality, it never describes it perfectly. It was Heisenberg's famous 'Uncertainty Principle' that showed the inevitable error between the real Quantum world and the measured world of pseudo-science.

Anyway, how can anyone measure the measurer, the mind? At a recent seminar on Science and Religion, at which I was a speaker, a Catholic in the audience bravely announced that whenever she looks through a telescope at the stars, she feels uncomfortable because her religion is threatened. I commented that whenever a scientist looks the other way round through a telescope, to observe the one who is watching, then they feel uncomfortable because their science is threatened by what is doing the seeing! So what is doing the seeing, what is this mind that eludes modern science?

A Grade-One teacher once asked her class "What is the biggest thing in the world?" One little girl answered "My daddy". A little boy said "An elephant", since he'd recently been to the zoo. Another girl suggested "A mountain". The six-year-old daughter of a close friend of mine replied, "My eye is the biggest thing in the world"! The class stopped. Even the teacher didn't understand her answer. So the little philosopher explained "Well, my eye can see her daddy, an elephant, and a mountain too. It can also see so much else. If all of that can fit into my eye, then my eye must be the biggest thing in the world"! Brilliant.

However, she was not quite right. The mind can see everything that one's eye can see, and it can also imagine so much more. It can also hear, smell, taste and touch, as well as think. In fact, everything that can be known can fit into the mind. Therefore, the mind must be the biggest thing in the world. Science's mistake is obvious now. The mind is not in the brain, nor in the body. The brain, the body and the rest of the world, are in the mind!

Mind is the sixth sense in Buddhism, it is that which encompasses the five senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch, and transcends them with its own domain. It corresponds loosely to Aristotle's "common sense" that is distinct from the five senses. Indeed, ancient Greek philosophy, from where science is said to have its origins, taught six senses just like Buddhism. Somewhere along the historical journey of European thinking, they lost their mind! Or, as Aristotle would put it, they somehow discarded their "common sense"! And thus we got science. We got materialism without any heart. One can accurately say that Buddhism is a science that has kept its heart, and which hasn't lost its mind!

Thus Buddhism is not a belief system. It is a science founded on objective observation, i.e. meditation, ever careful not to disturb the reality through imposing artificial measurements, and it is evidently repeatable.

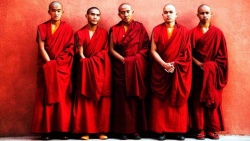

People have been re-creating the experimental conditions, known as establishing the factors of the Noble Eightfold Path, for over twenty-six centuries now, much longer than science. And those renowned Professors of Meditation, the male and female Arahants, have all arrived at the same conclusion as the Buddha. They verified the timeless Law of Dhamma, otherwise known as Buddhism. So Buddhism is the only real science, and I'm happy to say that I'm still a scientist at heart, only a much better scientist than I ever could have been at Cambridge.