Difference between revisions of "Nagarjuna and the Limits of Thought"

m (Text replacement - "application" to "application") |

m (Text replacement - "one thing" to "one thing") |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

Department of [[Philosophy]], {{Wiki|University}} of {{Wiki|Melbourne}} | Department of [[Philosophy]], {{Wiki|University}} of {{Wiki|Melbourne}} | ||

| − | ‘‘If you know the [[nature]] of | + | ‘‘If you know the [[nature]] of one thing, you know the [[nature of all things]].’’ |

[[Khensur]] Yeshe Thubten | [[Khensur]] Yeshe Thubten | ||

Latest revision as of 09:29, 4 February 2016

Jay L. Garfield

Department of Philosophy, Smith College and School of Philosophy, University of

Tasmania

Graham Priest

Department of Philosophy, University of Melbourne

‘‘If you know the nature of one thing, you know the nature of all things.’’

Khensur Yeshe Thubten

Whatever is dependently co-arisen, That is explained to be emptiness. That, being a dependent designation,

Is itself the middle way. (MMK XXIV : 18)

Introduction

Nagarjuna is surely one of the most difficult philosophers to interpret in any tradi- tion. His texts are terse and cryptic. He does not shy away from paradox or apparent contradiction. He is coy about identifying his opponents. The commentarial traditions grounded in his texts present a plethora of interpretations of his view. None- theless, his influence in the Mahayana Buddhist world is not only unparalleled in that tradition, but exceeds in that tradition the influence of any single Western phi- losopher in the West. The degree to which he is taken seriously by so many eminent Indian, Chinese, Tibetan, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese philosophers, and lately by so many Western philosophers, alone justifies attention to his corpus. Even were he not such a titanic figure historically, the depth and beauty of his thought and the austere beauty of his philosophical poetry would justify that attention. While Nagarjuna may perplex and often infuriate, and while his texts may initially defy exegesis, anyone who spends any time with Nagarjuna’s thought inevitably develops a deep respect for this master philosopher.

One of the reasons Nagarjuna so perplexes many who come to his texts is his seeming willingness to embrace contradictions, on the one hand, while making use of classic reductio arguments, implicating his endorsement of the law of non- contradiction, on the other. Another is his apparent willingness to saw off the limbs on which he sits. He asserts that there are two truths, and that they are one; that everything both exists and does not exist; that nothing is existent or nonexistent; that he rejects all philosophical views including his own; that he asserts nothing. And he appears to mean every word of it. Making sense of all of this is sometimes difficult. Some interpreters of Nagarjuna, indeed, succumb to the easy temptation to read him as a simple mystic or an irrationalist of some kind. But it is significant that none of

Philosophy East & West Volume 53, Number 1 January 2003 1–21 1

> 2003 by University of Hawai‘i Press

the important commentarial traditions in Asia, however much they disagree in other respects, regard him in this light.1 And, indeed, most recent scholarship is unani- mous in this regard as well, again despite a wide range of divergence in interpretations in other respects. Nagarjuna is simply too committed to rigorous analytical argument to be dismissed as a mystic.

Our interest here is neither historical nor in providing a systematic exegesis or assessment of any of Nagarjuna’s work. Instead, we are concerned with the possi- bility that Nagarjuna, like many philosophers in the West, and indeed like many of his Buddhist successors—perhaps as a consequence of his influence—discovers and explores true contradictions arising at the limits of thought. If this is indeed the case, it would account for both sides of the interpretive tension just noted: Nagarjuna might appear to be an irrationalist by virtue of embracing some contradictions—both to Western philosophers and to Nyaya interlocutors, who see consistency as a necessary condition of rationality. But to those who share with us a dialetheist’s comfort with the possibility of true contradictions commanding rational assent, for Nagarjuna to endorse such contradictions would not undermine but instead would confirm the impression that he is indeed a highly rational thinker.2

We are also interested in the possibility that these contradictions are structurally analogous to those arising in the Western tradition. But while discovering a parallel between Nagarjuna’s thought and those of other paraconsistent frontiersmen such as Kant, Hegel, Heidegger, and Derrida may help Western philosophers to understand Nagarjuna’s project better, or at least might be a philosophical curio, we think we can deliver more than that: we will argue that while Nagarjuna’s contradictions are structurally similar to those that we find in the West, Nagarjuna delivers to us a paradox as yet unknown in the West. This paradox, we will argue, brings us a new insight into ontology and into our cognitive access to the world. We should read Nagarjuna, then, not because in him we can see affirmed what we already knew, but because we can learn from him.

One last set of preliminary remarks is in order before we get down to work: in this essay we will defend neither the reading of Nagarjuna’s texts that we adopt here, nor the cogency of dialethic logic, nor the claim that true contradictions satisfying the Inclosure Schema in fact emerge at the limits of thought. We will sketch these views, but will do so fairly baldly. This is not because we take these positions to be self-evident, but because each of us has defended our respective bits of this back- ground elsewhere. This essay will be about bringing Nagarjuna and dialetheism together. Finally, we do not claim that Nagarjuna himself had explicit views about logic, or about the limits of thought. We do, however, think that if he did, he had the views we are about to sketch. This is, hence, not textual history but rational recon- struction.

Inclosures and the Limits of Thought

In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein takes on the project of delimiting what can be thought. He says in the Preface:

the expression of thoughts: for in order to be able to draw a limit to thought, we should have to find both sides thinkable (i.e., we should have to be able to think what cannot be thought). It will therefore be only in language that the limit can be drawn, and what lies on the other side of the limit will simply be nonsense. ([1921] 1988, p. 3)

Yet, even having reformulated the problem in terms of language, the enterprise still runs into contradiction. In particular, the account of what can be said has as a consequence that it itself, and other things like it, cannot be said. Hence, we get the famous penultimate proposition of the Tractatus:

My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has used them—as steps—to climb up beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.) ([1921] 1988, p. 74)

Wittgenstein’s predicament is serious. No matter that we throw away the ladder after we have climbed it: its rungs were nonsensical while we were using them as well. So how could it have successfully scaffolded our ascent? And if it didn’t, on what basis are we now to agree that all of that useful philosophy was nonsense all along? This predicament, however, is not peculiar to him. It is a quite general feature of theories that try to characterize the limits of our cognitive abilities to think, describe, grasp, that they end up implying that they themselves cannot be thought, described, or grasped. Yet it would appear that they can be thought, described, and grasped. Otherwise, what on earth is the theory doing?

Thus, for example, when Sextus claims in Outlines of Pyrrhonism that it is impossible to assert anything about things beyond appearances, he would seem to be asserting just such a thing; and when he argues that no such assertion is justified, this must apply to his own assertion as well. When Kant says that it is impossible to know anything about, or apply any categories to, the noumenal realm, he would seem to be doing just what cannot be done. When Russell attempts to solve the paradoxes of self-reference by claiming that it is impossible to quantify over all objects, he does just that. And the list goes on. Anyone who disparages the philosophical traditions of the East on account of their supposed flirtation with paradox has a lot of the West to explain away.

Of course, the philosophers we just mentioned were well aware of the situation, and all of them tried to take steps to avoid the contradiction. Arguably, they were not successful. Even more striking: characteristically, such attempts seem to end up in other instances of the very contradictions they are trying to avoid. The recent literature surrounding the Liar Paradox provides a rich diet of such examples.3

Now, why does this striking pattern occur again and again? The simplest answer is that when people are driven to contradictions in charting the limits of thought, it is precisely because those limits are themselves contradictory. Hence, any theory of the limits that is anywhere near adequate will be inconsistent. The recurrence of the encounter with limit contradictions is therefore the basis of an argument to the best explanation for the inconsistent nature of the limits themselves. (It is not

the only argument. But other arguments draw on details of the particular limits in question.4)

The contradictions at the limits of thought have a general and bipartite structure.

The first part is an argument to the effect that a certain view, usually about the nature of the limit in question, transcends that limit (cannot be conceived, described, etc.). This is Transcendence. The other is an argument to the effect that the view is within the limit—Closure. Often, this argument is a practical one, based on the fact that Closure is demonstrated in the very act of theorizing about the limits. At any rate, together, the pair describe a structure that can conveniently be called an inclosure: a totality, n and an object, o, such that o both is and is not in n.

On closer analysis, inclosures can be found to have a more detailed structure. At its simplest, the structure is as follows. The inclosure comes with an operator, d, which, when applied to any suitable subset of n, gives another object that is in n (that is, one that is not in the subset in question, but is in n). Thus, for example, if we are talking about sets of ordinals, d might apply to give us the least ordinal not in the set. If we are talking about a set of entities that have been thought about, d might give us an entity of which we have not yet thought. The contradiction at the limit arises when d is applied to the totality n itself. For then the application of d gives an object that is both within and without n: the least ordinal greater than all ordinals, or the unthought object.

All of the above is cataloged in Graham Priest, Beyond the Limits of Thought (Priest 2002). The catalog of limit contradictions there is not exhaustive, though. In particular, it draws only on Western philosophy. In what follows, we will add to the list the contradictions at the limits of thought discovered by Nagarjuna. As we will see, these, too, fit the familiar pattern. The fact that they do so, while coming from a quite different tradition, shows that the pattern is even less parochial than one might have thought. This should not, of course, be surprising: if the limits of thought really are contradictory, then they should appear so from both east and west of the Euphrates.

One way in which Nagarjuna does differ from the philosophers we have so far

mentioned, though, is that he does not try to avoid the contradiction at the limits of thought. He both sees it clearly and endorses it. (In the Western tradition, fewphi- losophers other than Hegel and some of his successors have done this.) Moreover, Nagarjuna seems to have hit upon a limit contradiction unknown in the West, and to suggest connections between ontological and semantic contradictions worthy of attention.

To Nagarjuna, then.

Conventional and Ultimate Reality

Central to Nagarjuna’s view is his doctrine of the two realities. There is, according to Nagarjuna, conventional reality and ultimate reality. Correspondingly, there are two truths: conventional truth, that is, the truth about conventional reality, and ultimate truth, or the truth about the ultimate reality—qua ultimate reality.5 For this reason, two realities.

The things that are conventionally true are the truths concerning the empirical world. Nagarjuna generally calls this class of truths samvrti-satya, or occasionally vyavaha¯ ra-satya. The former is explained by Nagarjuna’s ˙ ˙r Candrak¯ırti to commentato be ambiguous. The first sense—the one most properly translated into English as ‘‘conventional truth (reality)’’ (Tibetan: tha snyad bden pa)—is itself in three ways ambiguous. On the one hand, it can mean ordinary, or everyday. In this sense a conventional truth is a truth to which we would ordinarily assent—common sense augmented by good science. The second of these three meanings is truth by agree- ment. In this sense, the decision in Australia to drive on the left establishes a con- ventional truth about the proper side of the road. A different decision in the U.S.A. establishes another. Conventional truth is, in this sense, often quite relative. (Can- drak¯ırti argues that, in fact, in the first sense it is also relative—relative to our sense organs, conceptual scheme, etc. In this respect he would agree with such Pyrrhonian skeptics as Sextus.) The final sense of this cluster is nominally true. To be true in this sense is to be true by virtue of a particular linguistic convention. So, for instance, the fact that shoes and boots are different kinds of things here, but are both instances of one kind in Tibetan—lham—makes their co-specificity or lack thereof a nominal matter. We English speakers, on the other hand, regard sparrows and crows both as members of a single natural superordinate kind, bird. Native Tibetan speakers dis- tinguish the bya (the full-sized avian) from the bya’u (the smaller relative). (Again, relativism about truth in this sense lurks in the background.)

But these three senses cluster as one family against which stands yet another principal meaning of samvrti. It can also mean concealing, hiding, obscuring, occluding. In this sense˙ ˙ captured by the Tibetan kun rdzob bden pa, literally

(aptly ‘‘costumed truth’’) a samvrti-satya is something that conceals the truth, or its real nature, or, as it is˙ ˙ glossed in the tradition, something that is regarded as

sometimes

a truth by an obscured or a deluded mind. Now, the Madhyamaka tradition, fol- lowing Candrak¯ırti, makes creative use of this ambiguity, noting, for instance, that what such truths conceal is precisely the fact that they are merely conventional (in any of the senses adumbrated above) or that an obscured mind is obscured precisely by virtue of not properly understanding the role of convention in constituting truth, et cetera.

This lexicographic interlude is important primarily so that when we explore Nagarjuna’s distinction between the conventional and the ultimate truth (reality), and between conventional and ultimate perspectives—the distinct stances toward the world that Nagarjuna distinguishes, taken by ordinary versus enlightened beings—the word ‘‘conventional’’ is understood with this cluster of connotations, all present in Nagarjuna’s treatment. Our primary concern as we get to the heart of this exploration will be, however, with the notion of ultimate truth (reality) ( parama¯ rtha- satya, literally ‘‘truth of the highest meaning,’’ or ‘‘truth of the highest object’’). This we can define negatively as the way things are, considered independently of con- vention, or positively as the way things are, when understood by a fully enlightened

being who does not mistake what is really conventional for something that belongs to the very nature of things.

What is ultimate truth/reality, according to Nagarjuna? To understand this, we

have to understand the notion of emptiness, which for Nagarjuna is emphatically not nonexistence but, rather, interdependent existence. For something to have an essence (Tibetan: rang bzhin; Sanskrit: svabha¯ va) is for it to be what it is, in and of itself, independently of all other things. (This entails, incidentally, that things that are essentially so are eternally so; for if they started to be, or ceased to be, then their so being would depend on other things, such as time.) To be empty is precisely to have no essence, in this sense.

The most important ultimate truth, according to Nagarjuna, is that everything is empty. Much of the Mu¯ lamadhyamakaka¯ rika¯ (henceforth MMK ) consists, in fact, of an extended set of arguments to the effect that everything that one might take to be an essence is, in fact, not so—that everything is empty of essence and of indepen- dent identity. The arguments are interesting and varied, and we will not go into them here. But just to give the flavor of them, a very general argument is to be found in MMK V. Here, Nagarjuna argues that the spatial properties (and, by analogy, all properties) of an object cannot be essential. For it would be absurd to suppose that the spatial location of an object could exist without the object itself—or, conversely, that there could be an object without location. Hence, location and object are interdependent.

From this it follows that there is no characterized

And no existing characteristic. (MMK V : 4a, b)

The existence in question here is, of course, ultimate existence. Nagarjuna is not denying the conventional existence of objects and their properties.

With arguments such as the preceding one, Nagarjuna establishes that every- thing is empty, contingently dependent on other things—dependently co-arisen, as it is often put.

We must take the ‘‘everything’’ here very seriously, though. When Nagarjuna claims that everything is empty, ‘‘everything’’ includes emptiness itself. The empti- ness of something is itself a dependently co-arisen property of that thing. The emp- tiness of emptiness is perhaps one of the most central claims of the MMK.6 Na¯ ga¯ r- juna devotes much of chapter 7 to this topic. In that chapter, using some of the more difficult arguments of the MMK, he reduces to absurdity the assumption that depen- dent co-arising is itself an (ultimately) existing property of things. We will not go into the argument here: it is its consequences that will concern us.

For Western philosophers it is very tempting to adopt a Kantian understanding of Nagarjuna (as is offered, e.g., in Murti 1955). Identify conventional reality with the phenomenal realm, and ultimate reality with the noumenal, and there you have it. But this is not Nagarjuna’s view. The emptiness of emptiness means that ultimate reality cannot be thought of as a Kantian noumenal realm. For ultimate reality is just as empty as conventional reality. Ultimate reality is hence only conventionally real! The distinct realities are therefore identical. As the Vimalak¯ırtinirdes´a-su¯ tra puts it,

‘‘To say this is conventional and this is ultimate is dualistic. To realize that there is no difference between the conventional and the ultimate is to enter the Dharma-door of nonduality,’’ or, as the Heart Su¯ tra puts it more famously, ‘‘Form is empty; emptiness is form; form is not different from emptiness; emptiness is not different from form.’’ The identity of the two truths has profound soteriological implications for Nagarjuna,

such as the identity of nirva¯ na and samsa¯ ra.7

But we will not go into these.

We are now nearly in a position to address the first of Nagarjuna’s limit contradictions.

Nagarjuna and the Law of Noncontradiction

Before we do this, however, there is one more preliminary matter we need to examine: Nagarjuna’s attitude toward the law of noncontradiction in the domain of conventional truth. For to charge Nagarjuna with irrationalism, or even with an extreme form of dialetheism, according to which contradictions are as numerous as blackberries, is, in part, to charge him with thinking that contradictions are true in the standard conventional realm. Although this view is commonly urged (see, e.g., Robinson 1957 and Wood 1994), it is wrong. Although Nagarjuna does endorse contradictions, they are not of a kind that concern conventional reality qua conventional reality.

We can get at this point in two ways. First, we can observe that Nagarjuna himself never asserts that there are true contradictions in this realm (or, more cautiously, that every apparent assertion of a contradiction concerning this domain, upon analysis, resolves itself into something else). Second, we can observe that Nagarjuna takes reductio arguments to be decisive in this domain. We confess: neither of these strategies is hermeneutically unproblematic. The first relies on careful and sometimes controversial readings of Nagarjuna’s dialectic. We will argue, using a couple of cases, that such readings are correct. Moreover, we add, such readings are defended in the canonical tradition by some of the greatest Madhyamaka exegetes.

The second strategy is hard because, typically, Nagarjuna’s arguments are directed as ad hominem arguments against specific positions defended by his adversaries, each of whom would endorse the law of noncontradiction. If we argue that Nagarjuna rejects the positions they defend by appealing to contradictory consequences of opponents’ positions that he regards as refutatory, it is always open to the irrationalist interpreter of Nagarjuna to reply that for the argument to be successful one needs to regard these only as refutations for the opponent. That is, according to this reading, Nagarjuna himself could be taken not to be finding contradictory consequences as problematic, but to be presenting a consequence un- acceptable to a consistent opponent, thereby forcing his opponent to relinquish the position on the opponent’s own terms. And indeed such a reading is cogent. So if we are to give this line of argument any probative force, we will have to show that in particular cases Nagarjuna himself rejects the contradiction and endorses the conventional claim whose negation entails the contradiction. We will present such examples.

Let us first consider the claim that Nagarjuna himself freely asserts contradictions. One might think, for instance, that when Nagarjuna says that

Therefore, space is not an entity. It is not a nonentity.

Not characterized, not without character.

The same is true of the other five elements (MMK V: 7)

he is endorsing the claim that space and the other fundamental elements have con- tradictory properties (existence and nonexistence, being characterized and being uncharacterized). But this reading would only be possible if one (as we have just done) lifts this verse out of context. The entire chapter in which it occurs is addressed to the problem of reification—to treating the elements as providing an ontological foundation for all of reality, that is, as essences. After all, he concludes in the very next verse:

Fools and reificationists who perceive

The existence and nonexistence Of objects

Do not see the pacification of objectification. (MMK V: 8)

It is then clear that Nagarjuna is not asserting that space and the other elements have contradictory properties. Rather, he is rejecting a certain framework in which they play the role of ultimate foundations, or the role of ultimate property bearers.

Moreover, although Western and non-Buddhist Indian commentators have urged that such claims are contradictory, we also note that they are not even prima facie contradictions unless one presupposes both the law of the excluded middle and that Nagarjuna himself endorses that law. Otherwise there is no way of getting from a verse that explicitly rejects both members of the pair ‘‘Space is an entity’’ and

‘‘Space is a nonentity’’ to the claim that, by virtue of rejecting each, he is accepting its negation and hence that he is asserting a contradiction. Much better to read Nagarjuna as rejecting the excluded middle for the kind of assertion the opponent in question is making, packed as it is with what Nagarjuna regards as illicit ontological presupposition (Garfield 1995).

Let us consider a second example. In his discussion of the aggregates, another context in which his concern is to dispose of the project of fundamental ontology, Nagarjuna says:

The assertion that the effect and cause are similar

Is not acceptable.

The assertion that they are not similar

Is also not acceptable. (MMK IV : 6)

Again, absent context, and granted the law of the excluded middle, this appears to be a bald contradiction. And again, context makes all the difference. The opponent in this chapter has been arguing that form itself (material substance) can be thought of as the cause of all psychophysical phenomena. In the previous verse Nagarjuna has just admonished the opponent to ‘‘think about form, but / Do not construct

theories about form’’ (5c–d). The point of this verse is just that form, per se, is a plausible explanation neither of the material world (this would beg the question) nor of the nonmaterial world (it fails to explain psychophysical relations). We are not concerned here with whether Nagarjuna is right or wrong in these cases. We want to point out only that in cases like this, where it might appear that Nagarjuna does assert contradictions, it is invariably the case that a careful reading of the text undermines the straightforwardly contradictory reading. And once again, we note that when it is read with logical circumspection, we have here, in any case, only a rejection in a particular context of the law of the excluded middle, and no warrant for moving from that rejection to any rejection of noncontradiction.

We now turn to the fact that Nagarjuna employs reductio arguments in order to

refute positions he rejects, showing that at least with regard to standard conventional situations, the fact that a claim entails contradictions is good reason to reject it. In chapter 15 of the MMK, Nagarjuna considers the possibility that what it is to exist and what it is to have a particular identity is to be explained by an appeal to essence. But he is able to conclude that

Those who see essence and essential difference

And entities and nonentities, They do not see

The truth taught by the Buddha (MMK XVI : 6)

precisely on the grounds that

If there is no essence,

What could become other? If there is essence,

What could become other? (MMK XV : 9)

In this argument, in lines c and d—the rest of whose details, and the question of the soundness of which, we leave aside for present purposes—Nagarjuna notes that an account of existence, change, and difference that appeals to essence leads to a contradiction. Things do ‘‘become other.’’ That is a central thesis of the Buddhist doctrine of impermanence that Nagarjuna defends in the text. But if they do, he argues, and if essence were explanatory of their existence, difference, and change, they would need both to have essence, in order to account for their existence, and to lack it, by virtue of the fact that essences are eternal. Since this is contradictory, essence is to be rejected. And of course, as we have already noted, Nagarjuna does reject essence. That is the central motivation of the text.

In chapter 17 Nagarjuna responds to the opponent’s suggestion that action may be something uncreated (XVII : 23), a desperate ploy to save the idea that actions have essences. He responds that

All conventions would then

Be contradicted, without doubt.

It would be impossible to draw a distinction

Between virtue and evil. (MMK XVII : 24)

Again, neither the details of the argument nor its success concerns us here. Rather, we emphasize the fact that, for Nagarjuna, contradictory consequences of positions in the standard conventional realm are fatal to these positions.

As a final example, we note that in chapter 18 Nagarjuna concludes:

Whatever comes into being dependent on another

Is not identical to that thing. Nor is it different from it.

Therefore it is neither nonexistent in time nor permanent. (MMK XVIII : 10)

Here Nagarjuna notes that the contradiction (not identical / not different) follows from the disjunction, ‘‘An entity is either nonexistent or permanent,’’ and so opts for the claim that existent phenomena are impermanent. We conclude, then, that not only does Nagarjuna not freely assert contradictions but also, when he employs them, at least when discussing standard conventional truth, he does so as the con- clusions of reductio arguments, whose point is to defend the negation of the claim he takes to entail these contradictions.

At this stage, then, we draw the following conclusions: Nagarjuna is not an irrationalist. He is committed to the canons of rational argument and criticism. He is not a mystic. He believes that reasoned argument can lead to the abandonment of error and to knowledge. He is not of the view that the conventional world, however nominal it may be, is riddled with contradictions.8 If Nagarjuna is to assert contradictions, they will be elsewhere, they will be defended rationally, and they will be asserted in the service of reasoned analysis.

The Ultimate Truth Is That There Is No Ultimate Truth

We are now in a position to examine Nagarjuna’s first limit contradiction. The centerpiece of his Madhyamaka or ‘‘middle way’’ philosophy is the thesis that everything is empty. This thesis has a profound consequence. Ultimate truths are those about ultimate reality. But since everything is empty, there is no ultimate reality. There are, therefore, no ultimate truths. We can get at the same conclusion another way. To express anything in language is to express truth that depends on language, and so this cannot be an expression of the way things are ultimately. All truths, then, are merely conventional.

Nagarjuna enunciates this conclusion in the following passages:

The Victorious ones have said

That Emptiness is the relinquishing of all views. For whomever emptiness becomes a view

That one will accomplish nothing. (MMK XIII : 8)

I prostrate to Gautama Who, through compassion Taught the true doctrine

Which leads to the relinquishing of all views. (MMK XXVII : 30)

Nagarjuna is not saying here that one must be reduced to total silence. He himself

certainly was not! The views that one must relinquish are views about the ultimate nature of reality. And there is no such thing as the ultimate nature of reality. That is what it is for all phenomena to be empty.

It might be thought that the rest is simply ineffable. Indeed, Nagarjuna is some-

times interpreted in this way, too (Gorampa 1990). But this, also, would be too simplistic a reading. There are ultimate truths. The MMK is full of them. For example, when Nagarjuna says

Something that is not dependently arisen

Such a thing does not exist. Therefore a nonempty thing Does not exist (MMK XXIV : 19)

he is telling us about the nature of ultimate reality. There are, therefore, ultimate truths. Indeed, that there is no ultimate reality is itself a truth about ultimate reality and is therefore an ultimate truth! This is Nagarjuna’s first limit contradiction.

There are various objections one might raise at this point in an attempt to save

Nagarjuna from (ultimate) inconsistency. Let us consider two. First, one might say that when Nagarjuna appears to assert ultimate truths, he is not really asserting any- thing. His utterances have some other function. One might develop this point in at least two different ways. First, one might say that Nagarjuna’s speech acts are to be taken not as acts of assertion but as acts of denial. It is as though, whenever someone else makes a claim about ultimate reality, Nagarjuna simply says ‘‘No!’’ This is to interpret Nagarjuna as employing a relentless via negativa. Alternatively, one might say that in these utterances Nagarjuna is not performing a speech act at all: he is merely uttering words with no illocutory force. In the same way, one may interpret Sextus as claiming that he, also, never made assertions: he simply uttered words, which, when understood by his opponents, would cause them to give up their views.9

While these strategies have some plausibility (and some ways of reading Bha¯ - vaviveka and Candrak¯ırti have them interpreting Nagarjuna in just this way), in the end the text simply cannot sustain this reading. There are just too many important passages in the MMK in which Nagarjuna[[]] is not simply denying what his opponents say, or saying things that will cause his opponents to retract, but where he is stating positive views of his own. Consider, for example, the central verse of the MMK:

Whatever is dependently co-arisen, That is explained to be emptiness. That, being a dependent designation,

Is itself the middle way. (MMK XXIV : 18)

Or consider Nagarjuna’s assertion that nirvana and samsara are identical:

˙ ˙

Whatever is the limit of nirvana,

That is the limit of cyclic existence.

There is not even the slightest difference between them, Or even the subtlest thing. (MMK XXV : 20)

These are telling it like it is.

The strategy of claiming that, in the relevant portions of the text, Nagarjuna is not making assertions gains some exegetical plausibility from the fact that sometimes Nagarjuna can be interpreted as describing his own utterances in this way. The locus classicus is the Vigrahavyavartanı, where Nagarjuna responds to a Nyaya charge that he has undermined his own claim to the emptiness of all things through his own commitment to his assertions. In his autocommentary to verse 29, he says:

If I had even one proposition thereby it would be just as you have said. Although if I had a proposition with the characteristic that you described I would have that fault, I have no proposition at all. Thus, since all phenomena are empty, at peace, by nature isolated, how could there be a proposition? How can there be a characteristic of a proposition? And how can there be a fault arising from the characteristic of a proposition? Thus, the statement ‘‘through the characteristic of your proposition you come to acquire the fault’’ is not true.

But context and attention to the structure of the argument make all the her- meneutic difference here. The Nyaya interlocutor has charged Nagarjuna not simply with asserting things but with a self-refutatory commitment to the existence of convention-independent truth-makers (propositions—pratijna¯ ) for the things he says, on pain of abandoning claims to the truth of his own theory. Nagarjuna’s reply does not deny that he is asserting anything. How could he deny that? Rather he asserts that his use of words does not commit him to the existence of any convention- independent phenomena (such as emptiness) to which those words refer. What he denies is a particular semantic theory, one he regards as incompatible with his doc- trine of the emptiness of all things precisely because it is committed to the claim that things have natures (Garfield 1996). Compare, in this context, Wittgenstein’s rejec- tion of the theory of meaning of the Tractatus, with its extralinguistic facts and propositions, in favor of the use-theory of the Investigations. We conclude that even the most promising textual evidence for this route to saving Nagarjuna from inconsistency fails.

A second way one might interpret Nagarjuna so as to save him from inconsistency is to suggest that the assertions Nagarjuna proffers that appear to be statements of ultimate truth state merely conventional, and not ultimate, truths after all. One might defend this claim by pointing out that these truths can indeed be expressed, and inferring that they therefore must be conventional, otherwise they would be ineffable. If this were so, then to say that there are no ultimate truths would simply be true, and not false. But this reading is also hard to sustain. For something to be an ultimate truth is for it to be the way a thing is found to be at the end of an analysis of its nature. When, for instance, a madhyamika says that things are ultimately empty, that claim can be cashed out by saying that when we analyze that thing, looking for its essence, we literally come up empty. The analysis never terminates with anything that can stand as an essence. But another way of saying this is to say that the result of this ultimate analysis is the discovery that all things are empty, and that they can be no other way. This, hence, is an ultimate truth about them. We might point out that

the Indo-Tibetan exegetical tradition, despite lots of other internecine disputes, is unanimous on this point.

There is, then, no escape. Nagarjuna’s view is contradictory.10 The contradiction is, clearly, a paradox of expressibility. Nagarjuna succeeds in saying the unsayable, just as much as Wittgenstein in the Tractatus. We can think (and characterize) reality only subject to language, which is conventional, so the ontology of that reality is all conventional. It follows that the conventional objects of reality do not ultimately (nonconventionally) exist. It also follows that nothing we say of them is ultimately true. That is, all things are empty of ultimate existence, and this is their ultimate nature and is an ultimate truth about them. They hence cannot be thought to have that nature, nor can we say that they do. But we have just done so. As Mark Siderits (1989) has put it, ‘‘the ultimate truth is that there is no ultimate truth.’’

Positive and Negative Tetralemmas: Conventional and Ultimate Perspectives

It may be useful to approach the contradiction at the limits of expressibility here by a different route: Nagarjuna’s unusual use of both positive and negative forms of the catushkoti, or classical Indian tetralemma. Classical Indian logic and rhetoric regards any proposition as defining a logical space involving four candidate positions, or corners (koti), in distinction to most Western logical traditions, which consider only two—truth˙ and falsity. The proposition may be true (and not false), false (and not true), both true and false, or neither true nor false. As a consequence, Indian epistemology and metaphysics, including Buddhist epistemology and metaphysics, typically partitions each problem space defined by a property into four possibilities, not two.11 So Nagarjuna in the Mulamadhyamakakarika considers the possibility that motion, for instance, is in the moving object, not in the moving object, both in and not in the moving object, and neither in nor not in the moving object. Each prima facie logical possibility needs analysis before rejection.

Nagarjuna makes use both of positive and negative tetralemmas and uses this distinction in mood to mark the difference between the perspectives of the two truths. Positive tetralemmas, such as this, are asserted from the conventional per- spective:

That there is a self has been taught, And the doctrine of no-self,

By the buddhas, as well as the

Doctrine of neither self nor nonself. (MMK XVIII : 6)

Some, of course, interpret these as evidence for the irrationalist interpretation of Nagarjuna that we defused a few minutes ago. But if we are not on the lookout for contradictory readings of this, we can see Nagarjuna explaining simply how the policy of two truths works in a particular case. Conventionally, he says, there is a self—the conventional selves that we recognize as persisting from day to day, such as Jay and Graham, exist. But selves don’t exist ultimately. They both exist conventionally and are empty, and so fail to exist ultimately—indeed, these are exactly the

same thing. This verse therefore records neither inconsistency nor incompleteness. Rather, it affirms the two truths and demonstrates that we can talk coherently about both, and about their relationship—from the conventional perspective, of course.

The distinctively Na¯ ga¯ rjunian negative tetralemmas are more interesting. Here

Nagarjuna is after the limits of expressibility, and the contradictory situation at that limit when we take the ultimate perspective:

‘‘Empty’’ should not be asserted.

‘‘Nonempty’’ should not be asserted.

Neither both nor neither should be asserted. These are used only nominally. (MMK XXII : 11)

The last line makes it clear (as does context in the text itself ) that Nagarjuna is dis- cussing what can’t be said from the ultimate perspective—from a point of view transcendent of the conventional. And it turns out here that nothing can be said, even that all phenomena are empty. Nor its negation. We can’t even say that nothing can be said. But we just did. And we have thereby characterized the ultimate perspective, which, if we are correct in our characterization, can’t be done.

The relationship between these two kinds of tetralemma generates a higher- order contradiction as well. They say the same thing: each describes completely (although from different directions) the relationship between the two truths. The positive tetralemma asserts that conventional phenomena exist conventionally and can be characterized truly from that perspective, and that ultimately nothing exists or satisfies any description. In saying this, it in no way undermines its own cogency, and in fact affirms and explains its own expressibility. The negative counterpart asserts the same thing: that existence and characterization make sense at, and only at, the conventional level, and that, at the ultimate level, nothing exists or satisfies any description. But in doing so it contradicts itself: if true, it asserts its own non- assertability. The identity of the prima facie opposite two truths is curiously mirrored in the opposition of the prima facie identical two tetralemmas.

All Things Have One Nature, That Is, No Nature

We have examined the contradiction concerning the limits of expressibility that arises for Nagarjuna. But as will probably be clear already, there is another, and more fundamental, contradiction that underlies this. This is the ontological contra- diction concerning emptiness itself. All things, including emptiness itself, are, as we have seen, empty. As Nagarjuna puts it in a verse that is at the heart of the MMK:

Whatever is dependently co-arisen, That is explained to be emptiness. That, being a dependent designation,

Is itself the middle way. (MMK XXIV : 18)

Now, since all things are empty, all things lack any ultimate nature, and this is a characterization of what things are like from the ultimate perspective. Thus, ulti-

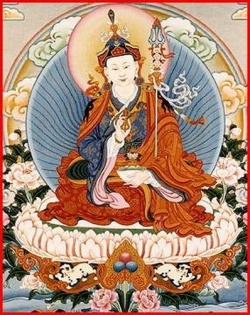

[[File:Padma yum.jpg|thumb|250px|]]

mately, things are empty. But emptiness is, by definition, the lack of any essence or ultimate nature. Nature, or essence, is just what empty things are empty of. Hence, ultimately, things must lack emptiness. To be ultimately empty is, ultimately, to lack emptiness. In other words, emptiness is the nature of all things; by virtue of this they have no nature, not even emptiness. As Nagarjuna puts it in his autocommentary to

the Vigrahavya¯ vartan¯ı, quoting lines from the Astasahasrika-prajn˜ a¯ pa¯ ramita¯ -su¯ tra:

‘‘All things have one nature, that is, no nature.’’ ˙˙

Nagarjuna’s enterprise is one of fundamental ontology, and the conclusion he comes to is that fundamental ontology is impossible. But that is a fundamentally ontological conclusion—and that is the paradox. There is no way that things are ultimately, not even that way. The Indo-Tibetan tradition, following the Vimalak¯ırti- nirdes´a-su¯ tra, hence repeatedly advises one to learn to ‘‘tolerate the groundlessness of things.’’ The emptiness of emptiness is the fact that not even emptiness exists ultimately, that it is also dependent, conventional, nominal, and, in the end, that it is just the everydayness of the everyday. Penetrating to the depths of being, we find ourselves back on the surface of things, and so discover that there is nothing, after all, beneath these deceptive surfaces. Moreover, what is deceptive about them is simply the fact that we take there to be ontological depths lurking just beneath.

There are, again, ways that one might attempt to avoid the ontological contra- diction. One way is to say that Nagarjuna’s utterances about emptiness are not assertions at all. We have discussed this move in connection with the previous limit contradiction. Another way, in this context, is to argue that even though Nagarjuna is asserting that everything is empty, the emptiness in question must be understood as an accident, and not an essence, to use Aristotelian jargon. Again, although this exegetical strategy may have some plausibility, it cannot be sustained. For things do not simply happen to be empty, as some things happen to be red. The arguments of the MMK are designed to show that all things cannot but be empty, that there is no other mode of existence of which they are capable. Since emptiness is a necessary characteristic of things, it belongs to them essentially—it is part of the very nature of phenomena per se. As Candrak¯ırti puts it, commenting on MMK XIII : 8:

As it is said in the great Ratnaku¯ ta-su¯ tra, ‘‘Things are not empty because of emptiness; to be a thing is to be empty.

Things are not without defining characteristics through characteristiclessness; to be a thing is to be without a defining characteristic. . . . [W]hoever understands things in this way, Kas´yapa, will understand perfectly how everything has been explained to be in the middle path.’’

To be is to be empty. That is what it is to be. It is no accidental property; it is something’s nature—although, being empty, it has no nature.

This paradox is deeply related to the first one that we discussed. One might fairly

ask, as have many on both sides of this planet, just why paradoxes of expressibility arise. The most obvious explanations might appear to be semantic in character, adverting only to the nature of language. One enamored of Tarski’s treatment of truth in a formal language might, for instance, take such a route. One might then regard limit paradoxes as indicating a limitation of language, an inadequacy to a reality that

must itself be consistent, and whose consistency would be mirrored in an adequate language. But Nagarjuna’s system provides an ontological explanation and a very different attitude toward these paradoxes, and, hence, to language. Reality has no nature. Ultimately, it is not in any way at all. So nothing can be said about it. Essencelessness thus induces non-characterizability. But, on the other side of the street, emptiness is an ultimate character of things. And this fact can ground the (ultimate) truth of what we have just said. The paradoxical linguistic utterances are therefore grounded in the contradictory nature of reality.

We think that the ontological insight of Nagarjuna’s is distinctive of the Madhyamaka; it is hard to find a parallel in the West prior to the work of Heidegger.12

But even Heidegger does not follow Nagarjuna all the way in the dramatic insistence on the identity of the two realities and the recovery of the authority of the conven- tional. This extirpation of the myth of the deep may be Nagarjuna’s greatest contri- bution to Western philosophy.

Nagarjuna and Inclosure

Everything is real and is not real, Both real and not real,

Neither real nor not real.

This is Lord Buddha’s teaching. (MMK XVIII : 8)

Central to Nagarjuna’s understanding of emptiness as immanent in the con- ventional world is his doctrine of the emptiness of emptiness. That, we have seen, is what prevents the two truths from collapsing into an appearance/reality or phenomenon/noumenon distinction. But it is also what generates the contradictions characteristic of philosophy at the limits. We have encountered two of these, and have seen that they are intimately connected. The first is a paradox of expressibility: linguistic expression and conceptualization can express only conventional truth; the ultimate truth is that which is inexpressible and that which transcends these limits. So it cannot be expressed or characterized. But we have just done so. The second is a paradox of ontology: all phenomena, Nagarjuna argues, are empty, and so ulti- mately have no nature. But emptiness is, therefore, the ultimate nature of things. So they both have and lack an ultimate nature.

That these paradoxes involve Transcendence should be clear. In the first case, there is an explicit claim that the ultimate truth transcends the limits of language and of thought. In the second case, Nagarjuna claims that the character of ultimate reality transcends all natures. That they also involve Closure is also evident. In the first case, the truths are expressed and hence are within the limits of expressibility; and in the second case, the nature is given and hence is within the totality of all natures.

Now consider the Inclosure Schema, introduced earlier, in a bit more detail. It concerns properties, j and c, and a function, d, satisfying the following conditions:

(1) n ¼ fJ: jðJÞg exists, and cðnÞ. (2) For all > J n such that cð>Þ:

(i) sdð>Þe> (Transcendence) (ii) dð>Þen (Closure)

Applying d to n then gives: dðnÞen and sdðnÞen. In a picture, we may represent the situation thus:

Fig. 1. Inclosure Schema.

In Nagarjuna’s ontological contradiction, an inclosure is formed by taking:

0 jðJÞ) as ‘J is empty’

0 cð>Þ as ‘> is a set of things with some common nature’

0 dð>Þ as ‘the nature of things in >’

To establish that this is an inclosure, we first note that cðnÞ. For n is the set of things that have the nature of being empty. Now assume that > J n and cð>Þ, that is, that > is a set of things with some common nature. dð>Þ is that nature, and dð>JÞen since all things are empty (Closure). It follows from this that dð>Þ has no nature. Hence, sdð>Þe>, since > is a set of things with some nature (Transcendence). The limit contradiction is that the nature of all things dðnÞ—namely emptiness— both is and is not empty. Or, to quote Nagarjuna, quoting the Prajnaparamita¯ , ‘‘All things have one nature, that is, no nature.’’

In Nagarjuna’s expressibility contradiction, an inclosure is formed by taking:

0 jðJÞ as ‘J is an ultimate truth’

0 cð>Þ as ‘> is definable’

0 dð>Þ as the sentence ‘there is nothing which is in D’, where ‘D’ refers to >. (If > is definable, there is such a D.)

To establish that this is an inclosure, we first note that cðnÞ. For ‘{J: J is an ultimate truth}’ defines n.

Now assume that > J n and cð>Þ; then dð>Þ is a sentence that says that nothing is in >. Call this s. It is an ultimate truth that there are no ultimate truths; that is, that there is nothing in n, and, since > J n, it is an ultimate truth that there is nothing in

>. That is, s is ultimately true: sen (Closure). For Transcendence, suppose that se>. Then sen; that is, s is an ultimate truth, and so true, that is, nothing is in >. Hence, it is not the case that se>. The limit contradiction is that dðnÞ, the claim that there are no ultimate truths, both is and is not an ultimate truth.

Thus, Nagarjuna’s paradoxes are both, precisely, inclosure contradictions. These

contradictions are unavoidable once we see emptiness as Nagarjuna characterizes it—as the lack of any determinate character. But this does not entail that Nagarjuna is an irrationalist, a simple mystic, or crazy; on the contrary: he is prepared to go exactly where reason takes him: to the transconsistent.

Nagarjuna’s Paradox and Others Like and Unlike It

Demonstrating that Nagarjuna’s two linked limit paradoxes satisfy a schema common to a number of well-known paradoxes in Western philosophy (the Liar, Mirimanoff ’s, the Burali-Forti, Russell’s, and the Knower, to name a few) goes further to normalizing Nagarjuna. We thus encounter him as a philosopher among familiar, respectable, philosophers, as a fellow traveler at the limits of epistemology and metaphysics. The air of irrationalism and laissez faire mysticism is thus dissipated once and for all. If Nagarjuna is beyond the pale, then so, too, are Kant, Hegel, Wittgenstein, and Heidegger.

This tool also allows us to compare Nagarjuna’s insights with those of his Western colleagues and to ask what, if anything, is distinctive about his results. We suggest the following: the paradox of expressibility, while interesting and important, and crucial to Nagarjuna’s philosophy of language (as well as to the development of Mahayana Buddhist philosophical practice throughout Central and East Asia), is not Nagarjuna’s unique contribution (although he may be the first to discover and to mobilize it, which is no mean distinction in the history of philosophy). It recurs in the West in the work of Wittgenstein, Heidegger, and Derrida, to name a few, and shares a structure with such paradoxes as the Liar. Discovering that Nagarjuna shares this insight with many Western philosophers may help to motivate the study of Nagarjuna by Westerners, but it does not demonstrate that he has any special value to us.

The ontological paradox, on the other hand—which we hereby name ‘‘Nagarjuna’s Paradox’’—although, as we have seen, is intimately connected with a paradox of expressibility, is quite distinctive, and to our knowledge is found nowhere else. If Nagarjuna is correct in his critique of essence, and if it thus turns out that all things lack fundamental natures, it turns out that they all have the same nature, that is, emptiness, and hence both have and lack that very nature. This is a direct consequence of the purely negative character of the property of emptiness, a prop- erty Nagarjuna first fully characterizes, and the centrality of which to philosophy he first demonstrates. Most dramatically, Nagarjuna demonstrates that the emptiness of emptiness permits the ‘‘collapse’’ of the distinction between the two truths, revealing the empty to be simply the everyday, and so saves his ontology from a simple-minded dualism. Nagarjuna demonstrates that the profound-limit contradic- tion he discovers sits harmlessly at the heart of all things. In traversing the limits of the conventional world, there is a twist, like that in a Mo¨ bius strip, and we find ourselves to have returned to it, now fully aware of the contradiction on which it rests.13

Notes

Thanks to Paul Harrison, Megan Howe, and Koji Tanaka for comments on earlier drafts of this essay and to our audience at the 2000 meeting of the Australasian Association of Philosophy and the Australasian Society for Asian and Comparative Philosophy, especially to Peter Forrest, Tim Oakley, and John Powers, for their comments and questions.

1 – Gorampa, in fourteenth-century Tibet, may be an exception to this claim, for in Nges don rab gsal he argues that Nagarjuna regards all thought and all con- ceptualization as necessarily totally false and deceptive. But even Gorampa agrees that Nagarjuna argues (and indeed soundly) for that conclusion.

2 – We note that Tillemans (1999) takes Nagarjuna’s sincere endorsement of con- tradictions to be possible evidence that he endorses paraconsistent logic with regard to the ultimate while remaining classical with regard to the conven- tional. We think he is right about this.

3 – For how this phenomenon plays out in the theories of Kripke and of Gupta and Herzberger, see Priest 1987, chap. 1; for the theory of Barwise and Etch- emendy, see Priest 1993; and for McGee, see Priest 1995.

4 – See Priest 1987 and 2002 for extended discussion.

5 – The reason for the qua qualification will become clear shortly. It will turn out that conventional and ultimate reality are, in a sense, the same.

6 – See, e.g., Garfield 1990, 1994, 1995, 1996; Huntington and Wangchen 1989; Kasulis 1989.

7 – These are taken up most notably in the Zen tradition (Kasulis 1989).

8 – On the other hand, it is no doubt true that in Nagarjuna’s view many of our pretheoretical and philosophical conceptions regarding the world are indeed riddled with incoherence. Getting them coherent is the task of the MMK.

9 – Although we take no position here on any debates in Sextus’ interpretation, or on whether Sextus is correct in characterizing his own method in this way.

10 – The fact that Nagarjuna’s view is inconsistent does not, of course—in his own view or in ours—mean that it is incoherent.

11 – See Hayes 1994 and Tillemans 1999 for excellent general discussions of the

catushkoti and its role in Indian logic and epistemology.

12 – On the paradoxical nature of being in Heidegger, see Priest 2001.

13 – Kasulis (1989) appropriately draws attention to the way in which Nagarjuna’s account of the way this traversal returns us to the conventional world, but with deeper insight into its conventional character; this is taken up by the great Zen philosopher Do¯ gen in his account of the great death and its consequent reaf- firmation of all things.

[[File:Padma 32.jpg|thumb|250px|]]

References

Bhattacarya, Kamaleswar, trans. and introd. 1985. The Dialectical Method of Nagarjuna: Vigrahavya¯ vartan¯ı. Critically edited by E. H. Johnston and Arnold Kunst. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Garfield, Jay L. 1990. ‘‘Epoche and S´ u¯ nyata¯ : Skepticism East and West.’’ Philosophy

East and West 40 : 285–307.

———. 1994. ‘‘Dependent Arising and the Emptiness of Emptiness: Why Did

Nagarjuna Start with Causation?’’ Philosophy East and West 44 : 219–250.

———. 1996. ‘‘Emptiness and Positionlessness: Do the Madhyamika Relinquish All

Views?’’ Journal of Indian Philosophy and Religion 1 : 1–34.

———, trans. and comment. 1995. The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way: Nagarjuna’s Mu¯ lamadhyamakaka¯ rika¯ . New York: Oxford University Press.

Gorampa. 1990. Nges don ran gsal. Sarnath: Sakya Students’ Union.

Hayes, R. 1994. ‘‘Nagarjuna’s Appeal.’’ Journal of Indian Philosophy 22 : 299–378. Huntington, C. W., with Geshe´ Namgyal Wangchen. 1989. The Emptiness of Emp-

tiness: An Introduction to Early Indian Ma¯ dhyamika. Honolulu: University of

Hawai‘i Press.

Kasulis, T. P. 1989. Zen Action / Zen Person. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. Murti, T.R.V. 1955. The Central Philosophy of Buddhism: A Study of the Ma¯ dhya-

mika System. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Priest, Graham. 1987. In Contradiction: A Study of the Transconsistent. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

———. 1993. ‘‘Another Disguise of the Same Fundamental Problems: Barwise and

Etchemendy on the Liar.’’ Australasian Journal of Philosophy 71 : 60–69.

———. 1995. Review of Vann McGee, Truth, Vagueness, and Paradox [Indianapo- lis: Hackett, 1990]. Mind 103 : 387–391.

———. 2002. Beyond the Limits of Thought, 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. ‘‘The Grammar of Being.’’ In Richard Gaskin, ed., Grammar in Early Twen- tieth Century Philosophy. London: Routledge, 2001.

Robinson, Richard H. 1957. ‘‘Some Logical Aspects of Nagarjuna’s System.’’ Phi- losophy East and West 6 : 291–308.

———. 1972. ‘‘Did Nagarjuna Really Refute All Philosophical Views?’’ Philosophy

East and West 22 : 325–331.

Siderits, Mark. 1989. ‘‘Thinking on Empty: Madhyamika Anti-Realism and Canons of Rationality.’’ In Shlomo Biderman and Ben-Ami Scharfstein, eds., Rationality in Question: On Eastern and Western Views of Rationality. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Tillemans, Tom J. F. 1999. ‘‘Is Nagarjuna’s Logic Deviant or Non-Classical?’’ In Tom J. F. Tillemans, Scripture, Logic, Language: Essays on Dharmakirti and His Tibe- tan Successors. Boston: Wisdom Publications.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. [1921] 1988. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Translated by D. F. Pears and B. F. McGuiness, with the Introduction by Bertrand Russell. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Wood, Thomas E. 1994. Na¯ ga¯ rjunian Disputations: A Philosophical Journey through an Indian Looking-Glass. Monographs of the Society for Asian and Comparative Philosophy, no. 11. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.