Difference between revisions of "East Mountain Teaching"

m (1 revision: link fix) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

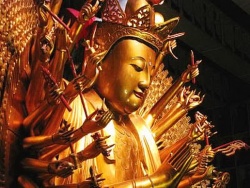

[[File:Url422.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Url422.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | '''East Mountain Teaching''' denotes the teachings of the Fourth Ancestor Dayi Daoxin, his student and heir the Fifth Ancestor Daman Hongren, and their students of the Chan lineage of China. | + | '''{{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Teaching]]''' denotes the teachings of the Fourth {{Wiki|Ancestor}} Dayi Daoxin, his student and heir the Fifth {{Wiki|Ancestor}} Daman Hongren, and their students of the [[Chan]] [[lineage]] of [[China]]. |

| − | East Mountain Teaching gets its name from the East Mountain Temple on 'Shuangfeng' ("Twin Peaks") of Huangmei. The East Mountain Temple was on the easternmost peak of the two. The label "East Mountain Teaching" (Chinese: 東山法門, dong shan fa men) is literally translated as the East Mountain [[Dharma]] Gate. It is also translated as the East Mountain School. | + | {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Teaching]] gets its [[name]] from the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Temple]] on 'Shuangfeng' ("Twin Peaks") of Huangmei. The {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Temple]] was on the easternmost peak of the two. The label "{{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Teaching]]" ({{Wiki|Chinese}}: 東山法門, dong shan fa men) is literally translated as the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Dharma]] Gate. It is also translated as the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain School. |

| − | The two most famous disciples of Hongren, Dajian Huineng and Yuquan Shenxiu, both were referred as continuing the East Mountain teaching. | + | The two most famous [[disciples]] of Hongren, Dajian [[Huineng]] and Yuquan [[Shenxiu]], both were referred as continuing the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[teaching]]. |

| − | ==History | + | =={{Wiki|History}} |

| − | The East Mountain School was established by Daoxin (道信 580–651)at East Mountain Temple on Potou (Broken Head) Mountain, which was later renamed Shuangfeng (Twin Peaks). Daoxin taught there for 30 years. He established the first monastic home for "Bodhidharma's Zen". | + | The {{Wiki|East}} Mountain School was established by Daoxin (道信 580–651)at {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Temple]] on Potou (Broken {{Wiki|Head}}) Mountain, which was later renamed Shuangfeng (Twin Peaks). Daoxin taught there for 30 years. He established the first [[monastic]] home for "Bodhidharma's [[Zen]]". |

| − | The tradition holds that Hongren (弘忍 601–674) left home at an early age (between seven and fourteen) and lived at East Mountain Temple on Twin Peaks, where Daoxiin was the abbot. | + | The [[tradition]] holds that Hongren (弘忍 601–674) left home at an early age (between seven and fourteen) and lived at {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Temple]] on Twin Peaks, where Daoxiin was the [[abbot]]. |

| − | : Upon Daoxin's death [in 651 C.E]. at the age of seventy-two, Hongren assumed the abbacy. He then moved East Mountain Temple approximately ten kilometers east to the flanks of Mt. Pingmu. Soon, Hongren's fame eclipsed that of his teacher. | + | : Upon Daoxin's [[death]] [in 651 C.E]. at the age of seventy-two, Hongren assumed the abbacy. He then moved {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Temple]] approximately [[ten]] kilometers {{Wiki|east}} to the flanks of Mt. Pingmu. Soon, Hongren's [[fame]] eclipsed that of his [[teacher]]. |

==Teachings== | ==Teachings== | ||

| − | The East Mountain community was a specialized meditation training centre. The establishment of a community in one location was a change from the wandering lives of Bodhiharma and Huike and their followers. It fitted better into the Chinese society, which highly valued community-oriented behaviour, instead of solitary practice | + | The {{Wiki|East}} Mountain community was a specialized [[meditation]] training centre. The establishment of a community in one location was a [[change]] from the wandering [[lives]] of Bodhiharma and Huike and their followers. It fitted better into the {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|society}}, which highly valued community-oriented {{Wiki|behaviour}}, instead of {{Wiki|solitary}} practice |

| − | An important aspect of the East Mountain Teachings was its nonreliance on a single [[Sutra]] or a single set of sutras for its doctrinal foundation as was done by most of the other Buddhist sects of the time. | + | An important aspect of the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain Teachings was its nonreliance on a single [[Sutra]] or a single set of [[sutras]] for its [[doctrinal]] foundation as was done by most of the other [[Buddhist]] sects of the [[time]]. |

| − | The East Mountain School incorporated both [[The Lankavatara Sutra]] and the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutras. | + | The {{Wiki|East}} Mountain School incorporated both [[The Lankavatara Sutra]] and the Mahaprajnaparamita [[Sutras]]. |

| − | The view of the mind in the Awakening of Faith in the [[Mahayana]] (Chinese: Ta-ch'eng ch'i-hsin lun) also had a significant import on the doctrinal development of the East Mountain Teaching.: | + | The [[view]] of the [[mind]] in the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] in the [[Mahayana]] ({{Wiki|Chinese}}: Ta-ch'eng ch'i-hsin lun) also had a significant import on the [[doctrinal]] development of the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Teaching]].: |

[[File:Url733.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Url733.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | : In the words of the Awakening of Faith — which summarizes the essentials of [[Mahayana]] — self and world, mind and suchness, are integrally one. Everything is a carrier of that a priori [[Enlightenment]]; all incipient [[Enlightenment]] is predicated on it. The mystery of existence is, then, not, "How may we overcome alienation?" The challenge is, rather, "Why do we think we are lost in the first place?" | + | : In the words of the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] — which summarizes the [[essentials]] of [[Mahayana]] — [[self]] and [[world]], [[mind]] and [[suchness]], are integrally one. Everything is a carrier of that a priori [[Enlightenment]]; all incipient [[Enlightenment]] is predicated on it. The {{Wiki|mystery}} of [[existence]] is, then, not, "How may we overcome alienation?" The challenge is, rather, "Why do we think we are lost in the first place?" |

===Daoxin=== | ===Daoxin=== | ||

| − | Daoxin is credited with several important innovations that led directly to the ability of Zen to become a popular religion. Among his most important contributions were: | + | Daoxin is credited with several important innovations that led directly to the ability of [[Zen]] to become a popular [[religion]]. Among his most important contributions were: |

| − | # The Unification of Zen practice with acceptance of the Buddhist precepts, | + | # The Unification of [[Zen]] practice with acceptance of the [[Buddhist]] [[precepts]], |

| − | # The unification of the teachings of [[The Lankavatara Sutra]] with those of the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutras, which includes the well-known Heart and Diamond sutras, | + | # The unification of the teachings of [[The Lankavatara Sutra]] with those of the Mahaprajnaparamita [[Sutras]], which includes the well-known [[Heart]] and [[Diamond]] [[sutras]], |

| − | # The incorporation of chanting, including chanting the name of Buddha, into Zen practice. | + | # The incorporation of [[chanting]], including [[chanting]] the [[name]] of [[Buddha]], into [[Zen]] practice. |

===Hongren=== | ===Hongren=== | ||

| − | Hongren was a plain meditation teacher, who taught students of "various religious interests", including "practitioners of the [[Lotus Sutra]], students of [[Madhyamaka]] philosophy, or specialists in the monastic regulations of Buddhist [[Vinaya]]". | + | Hongren was a plain [[meditation]] [[teacher]], who taught students of "various [[religious]] interests", including "practitioners of the [[Lotus Sutra]], students of [[Madhyamaka]] [[philosophy]], or specialists in the [[monastic]] regulations of [[Buddhist]] [[Vinaya]]". |

| − | Following Daoxin, Hongren included an emphasis on the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutras, including [[The Heart Sutra]] and [[The Diamond Sutra]], along with the emphasis on [[The Lankavatara Sutra]]. | + | Following Daoxin, Hongren included an emphasis on the Mahaprajnaparamita [[Sutras]], including [[The Heart Sutra]] and [[The Diamond Sutra]], along with the emphasis on [[The Lankavatara Sutra]]. |

| − | Though Hongren was known for not compiling writings and for teaching Zen principles orally, the classical Zen text Discourse on the Highest Vehicle, is attributed to him. This work emphasizes the practice of "maintaining the original true mind" that "naturally cuts off the arising of delusion." | + | Though Hongren was known for not compiling writings and for [[teaching]] [[Zen]] {{Wiki|principles}} orally, the classical [[Zen]] text {{Wiki|Discourse}} on the [[Highest]] [[Vehicle]], is attributed to him. This work emphasizes the practice of "maintaining the original true [[mind]]" that "naturally cuts off the [[arising]] of [[delusion]]." |

==Split in Northern and Southern School== | ==Split in Northern and Southern School== | ||

| − | Originally Shenxiu was considered to be the "Sixth Patriarch", carrying the mantle of Bodhidharma's Zen through the East Mountain School. After the death of Shenxiu, his student Heze Shenhui started a campaign to establish Huineng as the Sixth Ancestor. Eventually Shenhui's position won the day, and Huineng was recognized as the Sixth Patriarch. | + | Originally [[Shenxiu]] was considered to be the "[[Sixth Patriarch]]", carrying the mantle of Bodhidharma's [[Zen]] through the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain School. After the [[death]] of [[Shenxiu]], his student Heze Shenhui started a campaign to establish [[Huineng]] as the Sixth {{Wiki|Ancestor}}. Eventually Shenhui's position won the day, and [[Huineng]] was [[recognized]] as the [[Sixth Patriarch]]. |

| − | The successful promulgation of Shenhui's views led to Shenxiu's branch being widely referred to by others as the "Northern School." This nomenclature has continued in western scholarship, which for the most part has largely viewed Chinese Zen through the lens of southern Chan. | + | The successful promulgation of Shenhui's [[views]] led to Shenxiu's branch {{Wiki|being}} widely referred to by others as the "[[Northern School]]." This {{Wiki|nomenclature}} has continued in western {{Wiki|scholarship}}, which for the most part has largely viewed {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Zen]] through the lens of southern [[Chan]]. |

===Northern and Southern School=== | ===Northern and Southern School=== | ||

[[File:Urlbbn.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Urlbbn.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

The terms Northern and Southern have little to do with geography: | The terms Northern and Southern have little to do with geography: | ||

| − | : Contrary to first impressions, the formula has little to do with geography. Like the general designations of [[Mahāyāna]] ("great vehicle") and Hīnayāna ("little vehicle"), the formula carries with it a value judgement. According to the mainstream of later Zen, not only is sudden [[Enlightenment]] incomparably superior to gradual experience but it represents true Zen - indeed, it is the very touchstone of authentic Zen. | + | : Contrary to first [[impressions]], the [[formula]] has little to do with geography. Like the general designations of [[Mahāyāna]] ("[[great vehicle]]") and [[Hīnayāna]] ("little [[vehicle]]"), the [[formula]] carries with it a value [[judgement]]. According to the mainstream of later [[Zen]], not only is sudden [[Enlightenment]] incomparably {{Wiki|superior}} to gradual [[experience]] but it represents true [[Zen]] - indeed, it is the very touchstone of authentic [[Zen]]. |

| − | The basic difference is between approaches. Shenhui characterised the Northern School as employing gradual teachings, while his Southern school employed sudden teachings: | + | The basic [[difference]] is between approaches. Shenhui characterised the [[Northern School]] as employing gradual teachings, while his Southern school employed sudden teachings: |

| − | : suddenness of the South, gradualness of the North" (Chinese: nan-tun bei qian; Japanese: nanton hokuzen). | + | : suddenness of the {{Wiki|South}}, gradualness of the {{Wiki|North}}" ({{Wiki|Chinese}}: nan-tun bei qian; [[Japanese]]: nanton hokuzen). |

| − | The term "East Mountain Teaching" is seen as more culturally and historically appropriate. | + | The term "{{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Teaching]]" is seen as more culturally and historically [[appropriate]]. |

| − | But the characterization of Shenxiu's East Mountain Teaching as gradualist is argued to be unfounded in light of the documents found amongst manuscripts recovered from the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang. Shenhui's Southern School incorporated Northern teachings as well, and Shenhui himself admittedly saw the need of further practice after initial awakening. | + | But the characterization of Shenxiu's {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Teaching]] as gradualist is argued to be unfounded in [[light]] of the documents found amongst manuscripts recovered from the [[Mogao Caves]] near {{Wiki|Dunhuang}}. Shenhui's Southern School incorporated Northern teachings as well, and Shenhui himself admittedly saw the need of further practice after initial [[awakening]]. |

| − | ===Shenxiu (神秀, 606?-706 CE)=== | + | ===[[Shenxiu]] (神秀, 606?-706 CE)=== |

| − | Shenxiu's prominent position in the history of Chán, despite the popular narrative, is recognized by modern scholarship: | + | Shenxiu's prominent position in the {{Wiki|history}} of [[Chán]], despite the popular {{Wiki|narrative}}, is [[recognized]] by {{Wiki|modern}} {{Wiki|scholarship}}: |

| − | : No doubt the most important personage within the Northern school is [Shenxiu], a man of high education and widespread notoriety. | + | : No [[doubt]] the most important personage within the [[Northern school]] is [[[Shenxiu]]], a man of high [[education]] and widespread notoriety. |

| − | Kuiken (undated: p. 17) in discussing a Dunhuang document of the Tang [[Monk]] and meditator, 'Jingjue' (靜覺, 683- ca. 750) states: | + | Kuiken (undated: p. 17) in discussing a {{Wiki|Dunhuang}} document of the Tang [[Monk]] and [[meditator]], 'Jingjue' (靜覺, 683- ca. 750) states: |

| − | : Jingjue's Record introduces Hongren of Huangmei 黃梅宏忍 (d.u.) as the main teacher in the sixth generation of the 'southern' or 'East Mountain' meditation tradition. Shenxiu is mentioned as Hongren's authorized successor. In Shenxiu's shadow, Jingjue mentions 'old An' 老安 (see A) as a 'seasoned' meditation teacher and some minor 'local disciples' of Hongren. | + | : Jingjue's Record introduces Hongren of Huangmei 黃梅宏忍 (d.u.) as the main [[teacher]] in the sixth generation of the 'southern' or '{{Wiki|East}} Mountain' [[meditation]] [[tradition]]. [[Shenxiu]] is mentioned as Hongren's authorized successor. In Shenxiu's shadow, Jingjue mentions 'old An' 老安 (see A) as a 'seasoned' [[meditation]] [[teacher]] and some minor 'local [[disciples]]' of Hongren. |

===Hui-neng=== | ===Hui-neng=== | ||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

| − | The story of Huineng is famously worded in the Platform [[Sutra]], a text which originated after Shenhui's death. Its core may have originated within the so-called Oxhead school. The text was subsequently edited and enlarged, and reflects various Chán teachings. It de-emphasizes the difference between the Northern and the Southern School. | + | The story of [[Huineng]] is famously worded in the Platform [[Sutra]], a text which originated after Shenhui's [[death]]. Its core may have originated within the so-called Oxhead school. The text was subsequently edited and enlarged, and reflects various [[Chán]] teachings. It de-emphasizes the [[difference]] between the Northern and the Southern School. |

| − | The first chapter of the Platform [[Sutra]] relates the story of Huineng and his inheritance of the East Mountain Teachings. | + | The first chapter of the Platform [[Sutra]] relates the story of [[Huineng]] and his inheritance of the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain Teachings. |

| − | ==Wider influence of the East Mountain Teachings== | + | ==Wider [[influence]] of the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain Teachings== |

| − | The tradition of a list of patriarchs, which granted credibily to the developing tardition, developed early in the Chán tradition: | + | The [[tradition]] of a list of [[patriarchs]], which granted credibily to the developing tardition, developed early in the [[Chán]] [[tradition]]: |

| − | : The consciousness of a unique line of transmission of Bodhidharma Zen, which is not yet demonstrable in the Bodhidharma treatise, grew during the seventh century and must have taken shape on the East Mountain prior to the death of the Fourth Patriarch Tao-hsin (580-651). The earliest indication appears in the epitaph for Faru (638-689), one of the '10 outstanding disciples' of the Fifth Patriarch Hongren (601-674). The author of the epitaph is not known, but the list comprises six names: after Bodhidharma and Huike follow Sengcan, Daoxin, Hongren, and Faru. The Ch'uan fa-pao chi takes this list over and adds as a seventh name that of Shen-hsiu (605?-706) | + | : The [[consciousness]] of a unique line of [[transmission]] of [[Bodhidharma]] [[Zen]], which is not yet demonstrable in the [[Bodhidharma]] treatise, grew during the seventh century and must have taken [[shape]] on the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain prior to the [[death]] of the [[Fourth Patriarch]] Tao-hsin (580-651). The earliest indication appears in the epitaph for Faru (638-689), one of the '10 [[outstanding]] [[disciples]]' of the [[Fifth Patriarch]] Hongren (601-674). The author of the epitaph is not known, but the list comprises six names: after [[Bodhidharma]] and Huike follow Sengcan, Daoxin, Hongren, and Faru. The Ch'uan fa-pao [[chi]] takes this list over and adds as a seventh [[name]] that of Shen-hsiu (605?-706) |

===Faru (法如, 638-689 CE)=== | ===Faru (法如, 638-689 CE)=== | ||

| − | Faru (法如, 638-689) was "the first pioneer" and "actual founder" of the Northern School. His principal teachers were Hui-ming and Daman Hongren (Hung-jen). He was sent to Hongren by Hui-ming, and attained awakening when studying with Hung-jen | + | Faru (法如, 638-689) was "the first pioneer" and "actual founder" of the [[Northern School]]. His principal [[teachers]] were Hui-ming and Daman Hongren (Hung-jen). He was sent to Hongren by Hui-ming, and attained [[awakening]] when studying with Hung-jen |

| − | Originally Faru too was credited to be the successor of Hongren. But Faru did not have a good publicist, and he was not included within the list of Chan Patriarchs. | + | Originally Faru too was credited to be the successor of Hongren. But Faru did not have a good publicist, and he was not included within the list of [[Chan]] [[Patriarchs]]. |

| − | : In an epitaph for Shenxiu, his name is made to take the place of Faru's. The Leng-ch'ieh shih-tzu chi omits Faru and ends after Shenxiu with the name of his disciple Puji (651-739). These indications from the Northern school argue for the succession of the Third Patriarch Sengcan (d. 606), which has been thrown into doubt because of lacunae in the historical work of Tao-hsuan. Still, the matter cannot be settled with certainty. | + | : In an epitaph for [[Shenxiu]], his [[name]] is made to take the place of Faru's. The Leng-ch'ieh shih-tzu [[chi]] omits Faru and ends after [[Shenxiu]] with the [[name]] of his [[disciple]] Puji (651-739). These indications from the [[Northern school]] argue for the succession of the Third [[Patriarch]] Sengcan (d. 606), which has been thrown into [[doubt]] [[because of]] lacunae in the historical work of Tao-hsuan. Still, the [[matter]] cannot be settled with certainty. |

[[File:Urlcv.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Urlcv.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Because of Faru, the 'Shaolin Monastery', constructed in 496CE, yet again became prominent. [Faru] had only a brief stay at Shaolin Temple, but during his stay the cloister became the epicentre of the flourishing Chan movement. An epitaph commemorating the success of Faru's pioneering endeavors is located on Mount Sung. | + | Because of Faru, the '[[Shaolin]] [[Monastery]]', [[constructed]] in 496CE, yet again became prominent. [Faru] had only a brief stay at [[Shaolin Temple]], but during his stay the cloister became the epicentre of the flourishing [[Chan]] {{Wiki|movement}}. An epitaph commemorating the [[success]] of Faru's pioneering endeavors is located on Mount Sung. |

===Pao-t'ang (無住; Wu-chu; 714-774 CE)=== | ===Pao-t'ang (無住; Wu-chu; 714-774 CE)=== | ||

| − | [[Pao-t'ang Wu-chu]] or '[[Bao-tang Wu-zhu]]' (保唐无住) (Chinese: 無住; Wu-chu; 714-774CE), head and founder of Pao-t'ang Monastery (Chinese: 保唐寺) at Chengdu, Szechwan located in south west China was a member of the East Mountain Teachings as was Reverend Kim (Chin ho-shang). | + | [[Pao-t'ang Wu-chu]] or '[[Bao-tang Wu-zhu]]' (保唐无住) ({{Wiki|Chinese}}: 無住; Wu-chu; 714-774CE), {{Wiki|head}} and founder of [[Pao-t'ang Monastery]] ({{Wiki|Chinese}}: 保唐寺) at Chengdu, Szechwan located in {{Wiki|south}} {{Wiki|west}} [[China]] was a member of the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain Teachings as was Reverend Kim (Chin ho-shang). |

===Moheyan (late eighth century CE)=== | ===Moheyan (late eighth century CE)=== | ||

| − | Moheyan (late eighth century CE) was a proponent of the Northern School. Moheyan traveled to Dunhuang, which at the time belonged to the Tibetan Empire, in 781 or 787 CE. | + | Moheyan (late eighth century CE) was a proponent of the [[Northern School]]. Moheyan traveled to {{Wiki|Dunhuang}}, which at the [[time]] belonged to the [[Tibetan]] [[Empire]], in 781 or 787 CE. |

| − | Moheyan participated in a prolonged debate with Kamalashila at [[Samye]] in Tibet over sudden versus gradual teachings, which was decisive for the course the [[Tibetan Buddhist]] tradition took: | + | Moheyan participated in a prolonged [[debate]] with [[Kamalashila]] at [[Samye]] in [[Tibet]] over sudden versus gradual teachings, which was decisive for the course the [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[tradition]] took: |

| − | : As is well known, the fate of Chan [East Mountain Teachings] in Tibet was said to have been decided in a debate at the [[Samye Monastery]] near Lhasa in c.792-797. | + | : As is well known, the [[fate]] of [[Chan]] [{{Wiki|East}} Mountain Teachings] in [[Tibet]] was said to have been decided in a [[debate]] at the [[Samye Monastery]] near {{Wiki|Lhasa}} in c.792-797. |

| − | Broughton identifies the Chinese and Tibetan nomenclature of Mohoyen's teachings and identifies them principally with the East Mountain Teachings: | + | Broughton identifies the {{Wiki|Chinese}} and [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|nomenclature}} of Mohoyen's teachings and identifies them principally with the {{Wiki|East}} Mountain Teachings: |

| − | : Mo-ho-yen's teaching in Tibet as the famed proponent of the all-at-once gate can be summarized as "gazing-at-mind" (Chinese: k'an-hsin, Tibetan: sems la bltas) and "no examining" (Chinese: pu-kuan, Tibetan: myi rtog pa) or "no-thought no-examining" (Chinese: pu-ssu pu-kuan, Tibetan: myi bsam myi rtog). "Gazing-at-mind" is an original Northern (or East Mountain [[Dharma]] Gate) teaching. As will become clear, Poa-t'ang and the Northern Ch'an dovetail in the Tibetan sources. Mo-ho-yen's teaching seems typical of late Northern Ch'an. It should be noted that Mo-ho-yen arrived on the central Tibetan scene somewhat late in comparison to the Ch'an transmissions from Szechwan. | + | : Mo-ho-yen's [[teaching]] in [[Tibet]] as the famed proponent of the all-at-once gate can be summarized as "gazing-at-mind" ({{Wiki|Chinese}}: k'an-hsin, [[Tibetan]]: sems [[la]] bltas) and "no examining" ({{Wiki|Chinese}}: pu-kuan, [[Tibetan]]: myi rtog pa) or "no-thought no-examining" ({{Wiki|Chinese}}: pu-ssu pu-kuan, [[Tibetan]]: myi bsam myi rtog). "Gazing-at-mind" is an original Northern (or {{Wiki|East}} Mountain [[Dharma]] Gate) [[teaching]]. As will become clear, Poa-t'ang and the Northern [[Ch'an]] dovetail in the [[Tibetan]] sources. Mo-ho-yen's [[teaching]] seems typical of late Northern [[Ch'an]]. It should be noted that Mo-ho-yen arrived on the {{Wiki|central}} [[Tibetan]] scene somewhat late in comparison to the [[Ch'an]] transmissions from Szechwan. |

| − | The teachings of Moheyan and other Chan masters were unified with the Kham Dzogchen lineages {this may or may not be congruent with the Kahma (Tibetan: bka' ma) lineages} through the Kunkhyen (Tibetan for "omniscient"), [[Rongzom Chokyi Zangpo]]. | + | The teachings of Moheyan and other [[Chan]] [[masters]] were unified with the [[Kham]] [[Dzogchen]] [[lineages]] {this may or may not be congruent with the Kahma ([[Tibetan]]: bka' ma) [[lineages]]} through the Kunkhyen ([[Tibetan]] for "[[omniscient]]"), [[Rongzom Chokyi Zangpo]]. |

| − | The Dzogchen ("Great Perfection") School of the [[Nyingmapa]] was often identified with the 'sudden [[Enlightenment]]' (Tibetan: cig car gyi ‘jug pa) of Moheyan and was called to defend itself against this charge by avowed members of the Sarma lineages that held to the staunch view of 'gradual enlightenmnent' (Tibetan: rim gyis ‘jug pa). | + | The [[Dzogchen]] ("[[Great Perfection]]") School of the [[Nyingmapa]] was often identified with the 'sudden [[Enlightenment]]' ([[Tibetan]]: cig car gyi ‘jug pa) of Moheyan and was called to defend itself against this charge by avowed members of the [[Sarma]] [[lineages]] that held to the staunch [[view]] of 'gradual enlightenmnent' ([[Tibetan]]: rim gyis ‘jug pa). |

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

Revision as of 11:22, 17 September 2013

East Mountain Teaching denotes the teachings of the Fourth Ancestor Dayi Daoxin, his student and heir the Fifth Ancestor Daman Hongren, and their students of the Chan lineage of China.

East Mountain Teaching gets its name from the East Mountain Temple on 'Shuangfeng' ("Twin Peaks") of Huangmei. The East Mountain Temple was on the easternmost peak of the two. The label "East Mountain Teaching" (Chinese: 東山法門, dong shan fa men) is literally translated as the East Mountain Dharma Gate. It is also translated as the East Mountain School.

The two most famous disciples of Hongren, Dajian Huineng and Yuquan Shenxiu, both were referred as continuing the East Mountain teaching.

==History

The East Mountain School was established by Daoxin (道信 580–651)at East Mountain Temple on Potou (Broken Head) Mountain, which was later renamed Shuangfeng (Twin Peaks). Daoxin taught there for 30 years. He established the first monastic home for "Bodhidharma's Zen".

The tradition holds that Hongren (弘忍 601–674) left home at an early age (between seven and fourteen) and lived at East Mountain Temple on Twin Peaks, where Daoxiin was the abbot.

- Upon Daoxin's death [in 651 C.E]. at the age of seventy-two, Hongren assumed the abbacy. He then moved East Mountain Temple approximately ten kilometers east to the flanks of Mt. Pingmu. Soon, Hongren's fame eclipsed that of his teacher.

Teachings

The East Mountain community was a specialized meditation training centre. The establishment of a community in one location was a change from the wandering lives of Bodhiharma and Huike and their followers. It fitted better into the Chinese society, which highly valued community-oriented behaviour, instead of solitary practice

An important aspect of the East Mountain Teachings was its nonreliance on a single Sutra or a single set of sutras for its doctrinal foundation as was done by most of the other Buddhist sects of the time.

The East Mountain School incorporated both The Lankavatara Sutra and the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutras.

The view of the mind in the Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana (Chinese: Ta-ch'eng ch'i-hsin lun) also had a significant import on the doctrinal development of the East Mountain Teaching.:

- In the words of the Awakening of Faith — which summarizes the essentials of Mahayana — self and world, mind and suchness, are integrally one. Everything is a carrier of that a priori Enlightenment; all incipient Enlightenment is predicated on it. The mystery of existence is, then, not, "How may we overcome alienation?" The challenge is, rather, "Why do we think we are lost in the first place?"

Daoxin

Daoxin is credited with several important innovations that led directly to the ability of Zen to become a popular religion. Among his most important contributions were:

- The Unification of Zen practice with acceptance of the Buddhist precepts,

- The unification of the teachings of The Lankavatara Sutra with those of the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutras, which includes the well-known Heart and Diamond sutras,

- The incorporation of chanting, including chanting the name of Buddha, into Zen practice.

Hongren

Hongren was a plain meditation teacher, who taught students of "various religious interests", including "practitioners of the Lotus Sutra, students of Madhyamaka philosophy, or specialists in the monastic regulations of Buddhist Vinaya".

Following Daoxin, Hongren included an emphasis on the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutras, including The Heart Sutra and The Diamond Sutra, along with the emphasis on The Lankavatara Sutra.

Though Hongren was known for not compiling writings and for teaching Zen principles orally, the classical Zen text Discourse on the Highest Vehicle, is attributed to him. This work emphasizes the practice of "maintaining the original true mind" that "naturally cuts off the arising of delusion."

Split in Northern and Southern School

Originally Shenxiu was considered to be the "Sixth Patriarch", carrying the mantle of Bodhidharma's Zen through the East Mountain School. After the death of Shenxiu, his student Heze Shenhui started a campaign to establish Huineng as the Sixth Ancestor. Eventually Shenhui's position won the day, and Huineng was recognized as the Sixth Patriarch.

The successful promulgation of Shenhui's views led to Shenxiu's branch being widely referred to by others as the "Northern School." This nomenclature has continued in western scholarship, which for the most part has largely viewed Chinese Zen through the lens of southern Chan.

Northern and Southern School

The terms Northern and Southern have little to do with geography:

- Contrary to first impressions, the formula has little to do with geography. Like the general designations of Mahāyāna ("great vehicle") and Hīnayāna ("little vehicle"), the formula carries with it a value judgement. According to the mainstream of later Zen, not only is sudden Enlightenment incomparably superior to gradual experience but it represents true Zen - indeed, it is the very touchstone of authentic Zen.

The basic difference is between approaches. Shenhui characterised the Northern School as employing gradual teachings, while his Southern school employed sudden teachings:

- suddenness of the South, gradualness of the North" (Chinese: nan-tun bei qian; Japanese: nanton hokuzen).

The term "East Mountain Teaching" is seen as more culturally and historically appropriate.

But the characterization of Shenxiu's East Mountain Teaching as gradualist is argued to be unfounded in light of the documents found amongst manuscripts recovered from the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang. Shenhui's Southern School incorporated Northern teachings as well, and Shenhui himself admittedly saw the need of further practice after initial awakening.

Shenxiu (神秀, 606?-706 CE)

Shenxiu's prominent position in the history of Chán, despite the popular narrative, is recognized by modern scholarship:

- No doubt the most important personage within the Northern school is [[[Shenxiu]]], a man of high education and widespread notoriety.

Kuiken (undated: p. 17) in discussing a Dunhuang document of the Tang Monk and meditator, 'Jingjue' (靜覺, 683- ca. 750) states:

- Jingjue's Record introduces Hongren of Huangmei 黃梅宏忍 (d.u.) as the main teacher in the sixth generation of the 'southern' or 'East Mountain' meditation tradition. Shenxiu is mentioned as Hongren's authorized successor. In Shenxiu's shadow, Jingjue mentions 'old An' 老安 (see A) as a 'seasoned' meditation teacher and some minor 'local disciples' of Hongren.

Hui-neng

The story of Huineng is famously worded in the Platform Sutra, a text which originated after Shenhui's death. Its core may have originated within the so-called Oxhead school. The text was subsequently edited and enlarged, and reflects various Chán teachings. It de-emphasizes the difference between the Northern and the Southern School.

The first chapter of the Platform Sutra relates the story of Huineng and his inheritance of the East Mountain Teachings.

Wider influence of the East Mountain Teachings

The tradition of a list of patriarchs, which granted credibily to the developing tardition, developed early in the Chán tradition:

- The consciousness of a unique line of transmission of Bodhidharma Zen, which is not yet demonstrable in the Bodhidharma treatise, grew during the seventh century and must have taken shape on the East Mountain prior to the death of the Fourth Patriarch Tao-hsin (580-651). The earliest indication appears in the epitaph for Faru (638-689), one of the '10 outstanding disciples' of the Fifth Patriarch Hongren (601-674). The author of the epitaph is not known, but the list comprises six names: after Bodhidharma and Huike follow Sengcan, Daoxin, Hongren, and Faru. The Ch'uan fa-pao chi takes this list over and adds as a seventh name that of Shen-hsiu (605?-706)

Faru (法如, 638-689 CE)

Faru (法如, 638-689) was "the first pioneer" and "actual founder" of the Northern School. His principal teachers were Hui-ming and Daman Hongren (Hung-jen). He was sent to Hongren by Hui-ming, and attained awakening when studying with Hung-jen

Originally Faru too was credited to be the successor of Hongren. But Faru did not have a good publicist, and he was not included within the list of Chan Patriarchs.

- In an epitaph for Shenxiu, his name is made to take the place of Faru's. The Leng-ch'ieh shih-tzu chi omits Faru and ends after Shenxiu with the name of his disciple Puji (651-739). These indications from the Northern school argue for the succession of the Third Patriarch Sengcan (d. 606), which has been thrown into doubt because of lacunae in the historical work of Tao-hsuan. Still, the matter cannot be settled with certainty.

Because of Faru, the 'Shaolin Monastery', constructed in 496CE, yet again became prominent. [Faru] had only a brief stay at Shaolin Temple, but during his stay the cloister became the epicentre of the flourishing Chan movement. An epitaph commemorating the success of Faru's pioneering endeavors is located on Mount Sung.

Pao-t'ang (無住; Wu-chu; 714-774 CE)

Pao-t'ang Wu-chu or 'Bao-tang Wu-zhu' (保唐无住) (Chinese: 無住; Wu-chu; 714-774CE), head and founder of Pao-t'ang Monastery (Chinese: 保唐寺) at Chengdu, Szechwan located in south west China was a member of the East Mountain Teachings as was Reverend Kim (Chin ho-shang).

Moheyan (late eighth century CE)

Moheyan (late eighth century CE) was a proponent of the Northern School. Moheyan traveled to Dunhuang, which at the time belonged to the Tibetan Empire, in 781 or 787 CE.

Moheyan participated in a prolonged debate with Kamalashila at Samye in Tibet over sudden versus gradual teachings, which was decisive for the course the Tibetan Buddhist tradition took:

- As is well known, the fate of Chan [[[Wikipedia:East|East]] Mountain Teachings] in Tibet was said to have been decided in a debate at the Samye Monastery near Lhasa in c.792-797.

Broughton identifies the Chinese and Tibetan nomenclature of Mohoyen's teachings and identifies them principally with the East Mountain Teachings:

- Mo-ho-yen's teaching in Tibet as the famed proponent of the all-at-once gate can be summarized as "gazing-at-mind" (Chinese: k'an-hsin, Tibetan: sems la bltas) and "no examining" (Chinese: pu-kuan, Tibetan: myi rtog pa) or "no-thought no-examining" (Chinese: pu-ssu pu-kuan, Tibetan: myi bsam myi rtog). "Gazing-at-mind" is an original Northern (or East Mountain Dharma Gate) teaching. As will become clear, Poa-t'ang and the Northern Ch'an dovetail in the Tibetan sources. Mo-ho-yen's teaching seems typical of late Northern Ch'an. It should be noted that Mo-ho-yen arrived on the central Tibetan scene somewhat late in comparison to the Ch'an transmissions from Szechwan.

The teachings of Moheyan and other Chan masters were unified with the Kham Dzogchen lineages {this may or may not be congruent with the Kahma (Tibetan: bka' ma) lineages} through the Kunkhyen (Tibetan for "omniscient"), Rongzom Chokyi Zangpo.

The Dzogchen ("Great Perfection") School of the Nyingmapa was often identified with the 'sudden Enlightenment' (Tibetan: cig car gyi ‘jug pa) of Moheyan and was called to defend itself against this charge by avowed members of the Sarma lineages that held to the staunch view of 'gradual enlightenmnent' (Tibetan: rim gyis ‘jug pa).