Difference between revisions of "In search of the Guhyagarbha tantra"

m (Text replacement - "]]]" to "]])") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Vajrasattva2as.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Vajrasattva2as.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | The [[Guhyagarbha tantra]] is a [[vital]] part of [[Tibet’s]] [[Nyingma]] (“{{Wiki|ancient}}”) [[lineages]]. And yet, ever since the 11th century, when certain partisans of the new {{Wiki|translations}} questioned the authenticity of the Guhyagarbha [[tantra]], its {{Wiki|status}} became a disputed issue in [[Tibet]]. | + | The [[Guhyagarbha tantra]] is a [[vital]] part of [[Tibet’s]] [[Nyingma]] (“{{Wiki|ancient}}”) [[lineages]]. And yet, ever since the 11th century, when certain partisans of the new {{Wiki|translations}} questioned the authenticity of the [[Guhyagarbha]] [[tantra]], its {{Wiki|status}} became a disputed issue in [[Tibet]]. |

| − | The most detailed and sustained attack on the authenticity of the [[Guhyagarbha tantra]] was written by the 11th century translator [[Gö Khugpa Lhetse]], based on his failure to find any [[lineage]] for the [[tantra]] in [[India]] and the fact that, according to his [[judgement]], it didn’t resemble genuine [[Indian]] [[tantras]]. [[Gö Khugpa’s]] [[criticism]] was rather rash: {{Wiki|features}} which he found suspect in the [[Guhyagarbha]] are in fact also found in [[tantras]] of the new translation period that he accepted. Nevertheless, enough [[doubt]] remained that the [[tantra]] was excluded from the scriptural [[canon]] ([[bka’ ‘gyur]]) compiled in the 14th century. | + | The most detailed and sustained attack on the authenticity of the [[Guhyagarbha tantra]] was written by the 11th century [[translator]] [[Gö Khugpa Lhetse]], based on his failure to find any [[lineage]] for the [[tantra]] in [[India]] and the fact that, according to his [[judgement]], it didn’t resemble genuine [[Indian]] [[tantras]]. [[Gö Khugpa’s]] [[criticism]] was rather rash: {{Wiki|features}} which he found suspect in the [[Guhyagarbha]] are in fact also found in [[tantras]] of the [[new translation]] period that he accepted. Nevertheless, enough [[doubt]] remained that the [[tantra]] was excluded from the [[scriptural]] [[canon]] ([[bka’ ‘gyur]]) compiled in the 14th century. |

| − | According to some [[Nyingma]] apologists, [[Gö Khugpa]] attacked the [[tantra]] because he had been refused certain transmissions by [[Zurpoché Shakya Jungne]], one of the most influential [[Nyingma]] figures of that period. The story has some credibility, as [[Gö Khugpa]] is portrayed as a competitive and rather bad-tempered [[character]] in some non-[[Nyingma]] histories, including the [[Subtle Vajra]], the early [[Sakya]] {{Wiki|history}} translated by Cyrus Stearns in his [[book]] [[Luminous Lives]]. There we see [[Gö Khugpa]] falling out with his [[teacher]] [[Drogmi]] and trying to outdo him by travelling to [[Nepal]] to meet the [[great master]] [[Maitripa]] (in fact he meets [[Drogmi’s]] own [[teacher]] [[Gayadhara]], who fools him into [[thinking]] he is [[Maitripa]]). | + | According to some [[Nyingma]] apologists, [[Gö Khugpa]] attacked the [[tantra]] because he had been refused certain [[transmissions]] by [[Zurpoché Shakya Jungne]], one of the most influential [[Nyingma]] figures of that period. The story has some credibility, as [[Gö Khugpa]] is portrayed as a competitive and rather bad-tempered [[character]] in some non-[[Nyingma]] histories, [[including]] the [[Subtle Vajra]], the early [[Sakya]] {{Wiki|history}} translated by [[Cyrus Stearns]] in his [[book]] [[Luminous Lives]]. There we see [[Gö Khugpa]] falling out with his [[teacher]] [[Drogmi]] and trying to outdo him by travelling to [[Nepal]] to meet the [[great master]] [[Maitripa]] (in fact he meets [[Drogmi’s]] [[own]] [[teacher]] [[Gayadhara]], who fools him into [[thinking]] he is [[Maitripa]]). |

[[File:445454 guru.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:445454 guru.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | In any case, if [[Sakya]] [[scholars]] have not tended to join in these attacks on the [[Guhyagarbha tantra’s]] authenticity, it may be because [[Śākyaśrībhadra]], the [[Kashmiri]] [[guru]] who taught [[Sakya Paṇḍita]], verified a [[Sanskrit]] {{Wiki|manuscript}} of the [[tantra]] which had been found at [[Samyé]] (this is mentioned in a 12th or 13th century [[Sakya]] {{Wiki|biography}} of [[Śākyaśrībhadra]]). The {{Wiki|manuscript}} was passed from hand to hand until it reached [[Gö Lotsawa Zhönu Pal]], author of the [[Blue Annals]], who wrote: | + | In any case, if [[Sakya]] [[scholars]] have not tended to join in these attacks on the [[Guhyagarbha tantra’s]] authenticity, it may be because [[Śākyaśrībhadra]], the [[Kashmiri]] [[guru]] who [[taught]] [[Sakya Paṇḍita]], verified a [[Sanskrit]] {{Wiki|manuscript}} of the [[tantra]] which had been found at [[Samyé]] (this is mentioned in a 12th or 13th century [[Sakya]] {{Wiki|biography}} of [[Śākyaśrībhadra]]). The {{Wiki|manuscript}} was passed from hand to hand until it reached [[Gö Lotsawa Zhönu Pal]], author of the [[Blue Annals]], who wrote: |

| − | When the Great {{Wiki|Kashmiri}} [[Pandita]] ([[Śākyaśrī]]) arrived at [[Samyé]], he discovered the [[Sanskrit]] text of the [[Guhyagarbha]]. Later it came into the hands of [[Tatön Ziji]], who presented it to it [[Shagang Lotsawa]]. The latter sent the {{Wiki|manuscript}} to [[Chomden Rigpai Ralgri]], who accepted it and composed The [[Flower to Ornament]] the [[Accomplishment of the Guhyagarbha]]. He showed the text at an assembly of [[tantrikas]] at [[Mamoné]], and highly praised it. After that [[Tarpa Lotsawa]] made a translation of the Subsequent [[Guhyagarbha Tantra]] which had not been found before. Most of the pages of the {{Wiki|manuscript}} were damaged. The remaining pages of the [[Sanskrit]] {{Wiki|manuscript}} are in my hands. | + | When the Great {{Wiki|Kashmiri}} [[Pandita]] ([[Śākyaśrī]]) arrived at [[Samyé]], he discovered the [[Sanskrit]] text of the [[Guhyagarbha]]. Later it came into the hands of [[Tatön Ziji]], who presented it to it [[Shagang Lotsawa]]. The [[latter]] sent the {{Wiki|manuscript}} to [[Chomden Rigpai Ralgri]], who accepted it and composed The [[Flower to Ornament]] the [[Accomplishment of the Guhyagarbha]]. He showed the text at an assembly of [[tantrikas]] at [[Mamoné]], and highly praised it. After that [[Tarpa Lotsawa]] made a translation of the Subsequent [[Guhyagarbha Tantra]] which had not been found before. Most of the pages of the {{Wiki|manuscript}} were damaged. The remaining pages of the [[Sanskrit]] {{Wiki|manuscript}} are in my hands. |

| − | So the authenticity of the [[Guhyagarbha tantra]] seems to be rather a non-issue, despite all the polemical [[activity]] devoted to the question over the centuries in [[Tibet]]. Still, some may be [[interested]] in the [[Guhyagarbha]]-related {{Wiki|material}} that is to be found in the [[Dunhuang]] [[collections]]. While these manuscripts are alost certainly no earlier than the 10th century, they do provide some [[insights]] into the role of the [[Guhyagarbha]] in early [[Tibet]]: | + | So the authenticity of the [[Guhyagarbha tantra]] seems to be rather a non-issue, despite all the polemical [[activity]] devoted to the question over the centuries in [[Tibet]]. Still, some may be [[interested]] in the [[Guhyagarbha]]-related {{Wiki|material}} that is to be found in the [[Dunhuang]] [[collections]]. While these [[manuscripts]] are alost certainly no earlier than the 10th century, they do provide some [[insights]] into the role of the [[Guhyagarbha]] in early [[Tibet]]: |

[[File:Relie.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Relie.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Some of the [[sādhanas]] ([[manuals for meditation practice]]) quote the [[Guhyagarbha]], though this is a little inconclusive, since (i) it is difficult to find exact parallel passages in the [[tantra]] itself and (ii) the [[Guhyagarbha]] is not mentioned by [[name]]. See for example IOL Tib J 332, which was originally noticed by Ken Eastman in his article listed below. | + | Some of the [[sādhanas]] ([[manuals for meditation practice]]) quote the [[Guhyagarbha]], though this is a little inconclusive, since (i) it is difficult to find exact parallel passages in the [[tantra]] itself and (ii) the [[Guhyagarbha]] is not mentioned by [[name]]. See for example IOL Tib J 332, which was originally noticed by [[Ken Eastman]] in his article listed below. |

One {{Wiki|manuscript}} (IOL Tib J 540) is a list of the [[mantras]] and the names of each of the 42 [[deities]] from the [[Guhyagarbha‘s]] [[peaceful]] [[maṇḍala]]. | One {{Wiki|manuscript}} (IOL Tib J 540) is a list of the [[mantras]] and the names of each of the 42 [[deities]] from the [[Guhyagarbha‘s]] [[peaceful]] [[maṇḍala]]. | ||

One scroll, which I mentioned in the previous post (Pelliot tibétain 849), contains a list of [[tantras]] in [[Tibetan]] and [[Sanskrit]]. It includes the [[Guhyagarbha]]–listed as [[rgyud gsang ba’I snyIng po]] in [[Tibetan]] and ‘[[Gu yya kar rba tan tra]] in [[Sanskrit]] (the [[Sanskrit]] tranliterations on this scroll are wildly erratic). The scroll is, as I mentioned previously, probably notes from the teachings of an [[Indian]] [[guru]] who passed through [[Dunhuang]] on his way to [[China]]. However, it is dated to the very end of the 10th century, so this tells us little about the [[existence]] of the [[tantra]] in [[Tibet]] prior to this [[time]]. | One scroll, which I mentioned in the previous post (Pelliot tibétain 849), contains a list of [[tantras]] in [[Tibetan]] and [[Sanskrit]]. It includes the [[Guhyagarbha]]–listed as [[rgyud gsang ba’I snyIng po]] in [[Tibetan]] and ‘[[Gu yya kar rba tan tra]] in [[Sanskrit]] (the [[Sanskrit]] tranliterations on this scroll are wildly erratic). The scroll is, as I mentioned previously, probably notes from the teachings of an [[Indian]] [[guru]] who passed through [[Dunhuang]] on his way to [[China]]. However, it is dated to the very end of the 10th century, so this tells us little about the [[existence]] of the [[tantra]] in [[Tibet]] prior to this [[time]]. | ||

| − | Thus something of the [[Guhyagarbha tantra]] is there in the manuscripts, but it has a lesser presence than one might expect given its importance in the later [[Nyingma]] [[tradition]]. What is perhaps most striking is how many more references and quotations from a different [[tantra]], the [[Guhyasamāja]], are found among the manuscripts. The [[Guhyasamāja tantra]] itself appears in an almost complete {{Wiki|manuscript}} (IOL Tib J 438), and is quoted more often and by [[name]] in various treatises and [[sādhanas]]. This raises the question of whether the [[Guhyasamāja tantra]] was actually more influential in pre-11th century [[Tibet]] than the[[ Guhyagarbha tantra]]. | + | Thus something of the [[Guhyagarbha tantra]] is there in the [[manuscripts]], but it has a lesser presence than one might expect given its importance in the later [[Nyingma]] [[tradition]]. What is perhaps most striking is how many more references and quotations from a different [[tantra]], the [[Guhyasamāja]], are found among the [[manuscripts]]. The [[Guhyasamāja tantra]] itself appears in an almost complete {{Wiki|manuscript}} (IOL Tib J 438), and is quoted more often and by [[name]] in various treatises and [[sādhanas]]. This raises the question of whether the [[Guhyasamāja tantra]] was actually more influential in pre-11th century [[Tibet]] than the[[ Guhyagarbha tantra]]. |

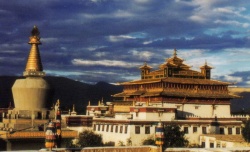

[[File:Samye051.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Samye051.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Perhaps the attacks on the [[Guhyagarbha]] and similar [[tantras]] were after all, as the [[Nyingma]] apologists suggest, {{Wiki|politically}} motivated. In the struggles between the holders of the old [[lineages]] (i.e. the incipient [[Nyingmapas]], the [[Zur]] family in particular) and the translators of the newly arrived [[tantric]] [[lineages]], the [[Guhyagarbha]] was an easy target, as it was not featured in any of the new [[lineages]], unlike the [[Guhyasamāja]]. Equally the [[Nyingmapas]] seem to have focussed more and more on the [[Guhyagarbha]] from the 11th century onward–perhaps exactly because it was not shared with the new schools. | + | Perhaps the attacks on the [[Guhyagarbha]] and similar [[tantras]] were after all, as the [[Nyingma]] apologists suggest, {{Wiki|politically}} motivated. In the struggles between the holders of the old [[lineages]] (i.e. the incipient [[Nyingmapas]], the [[Zur]] [[family]] in particular) and the [[translators]] of the newly arrived [[tantric]] [[lineages]], the [[Guhyagarbha]] was an easy target, as it was not featured in any of the new [[lineages]], unlike the [[Guhyasamāja]]. Equally the [[Nyingmapas]] seem to have focussed more and more on the [[Guhyagarbha]] from the 11th century onward–perhaps exactly because it was not shared with the new schools. |

References | References | ||

| − | 1. [[Dorje]], Gyurme. (no date). The [[Guhyagarbha Tantra]]: Introduction. Online at the [[Wisdom]] [[Books]] Reading Room | + | 1. [[Dorje]], [[Gyurme]]. (no date). The [[Guhyagarbha Tantra]]: Introduction. Online at the [[Wisdom]] [[Books]] Reading Room |

| − | 2. Eastman, Kenneth. 1983. “[[Mahāyoga]] Texts at [[Tun-huang]]”. Bulletin of the Institute of {{Wiki|Cultural}} Studies, Ryukoku {{Wiki|University}} 22: 42-60. | + | 2. Eastman, Kenneth. 1983. “[[Mahāyoga]] Texts at [[Tun-huang]]”. Bulletin of the Institute of {{Wiki|Cultural}} Studies, [[Ryukoku]] {{Wiki|University}} 22: 42-60. |

| − | 3. van der Kuijp, Leonard. 1994. “On the [[Lives]] of [[Śākyaśrībhadra]] (?-?1225)”. Journal of the American {{Wiki|Oriental}} {{Wiki|Society}} 114/4: 599–616. Available on JSTOR. | + | 3. [[van der Kuijp]], Leonard. 1994. “On the [[Lives]] of [[Śākyaśrībhadra]] (?-?1225)”. Journal of the [[American]] {{Wiki|Oriental}} {{Wiki|Society}} 114/4: 599–616. Available on JSTOR. |

4. Martin, Dan. 1987. “[[Illusion]] Web: Locating the [[Guhyagarbha Tantra]] in [[Buddhist]] | 4. Martin, Dan. 1987. “[[Illusion]] Web: Locating the [[Guhyagarbha Tantra]] in [[Buddhist]] | ||

| − | [[Intellectual]] {{Wiki|History}}”. Christopher I. Beckwith (ed.) Silver on Lapis: [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|Literary}} {{Wiki|Culture}} and {{Wiki|History}}. Bloomington: The [[Tibet]] {{Wiki|Society}}. 175-220. Available for free download here. | + | [[Intellectual]] {{Wiki|History}}”. Christopher I. Beckwith (ed.) {{Wiki|Silver}} on Lapis: [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|Literary}} {{Wiki|Culture}} and {{Wiki|History}}. [[Bloomington]]: The [[Tibet]] {{Wiki|Society}}. 175-220. Available for free download here. |

5. [[Roerich]]. (trans.) 1949. The [[Blue Annals]]. {{Wiki|Calcutta}}: {{Wiki|Royal Asiatic Society}} of {{Wiki|Bengal}}. (See pp.104-5.) Also available here. | 5. [[Roerich]]. (trans.) 1949. The [[Blue Annals]]. {{Wiki|Calcutta}}: {{Wiki|Royal Asiatic Society}} of {{Wiki|Bengal}}. (See pp.104-5.) Also available here. | ||

| − | 6. Stearns, Cyrus. 2001. Luminous [[Lives]]. Boston: [[Wisdom Publications]]. | + | 6. [[Stearns]], Cyrus. 2001. Luminous [[Lives]]. [[Boston]]: [[Wisdom Publications]]. |

| − | 7. [[Wangchuk]], Dorji. 2002. “An Eleventh-Century Defence of the Authenticity of the [[Guhyagarbha Tantra]]“. In Eimer and Germano (eds), The Many Canons of [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. Leiden: Brill. | + | 7. [[Wangchuk]], [[Dorji]]. 2002. “An Eleventh-Century Defence of the Authenticity of the [[Guhyagarbha Tantra]]“. In Eimer and [[Germano]] (eds), The Many Canons of [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. [[Leiden]]: Brill. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

Latest revision as of 19:34, 30 March 2024

The Guhyagarbha tantra is a vital part of Tibet’s Nyingma (“ancient”) lineages. And yet, ever since the 11th century, when certain partisans of the new translations questioned the authenticity of the Guhyagarbha tantra, its status became a disputed issue in Tibet.

The most detailed and sustained attack on the authenticity of the Guhyagarbha tantra was written by the 11th century translator Gö Khugpa Lhetse, based on his failure to find any lineage for the tantra in India and the fact that, according to his judgement, it didn’t resemble genuine Indian tantras. Gö Khugpa’s criticism was rather rash: features which he found suspect in the Guhyagarbha are in fact also found in tantras of the new translation period that he accepted. Nevertheless, enough doubt remained that the tantra was excluded from the scriptural canon (bka’ ‘gyur) compiled in the 14th century.

According to some Nyingma apologists, Gö Khugpa attacked the tantra because he had been refused certain transmissions by Zurpoché Shakya Jungne, one of the most influential Nyingma figures of that period. The story has some credibility, as Gö Khugpa is portrayed as a competitive and rather bad-tempered character in some non-Nyingma histories, including the Subtle Vajra, the early Sakya history translated by Cyrus Stearns in his book Luminous Lives. There we see Gö Khugpa falling out with his teacher Drogmi and trying to outdo him by travelling to Nepal to meet the great master Maitripa (in fact he meets Drogmi’s own teacher Gayadhara, who fools him into thinking he is Maitripa).

In any case, if Sakya scholars have not tended to join in these attacks on the Guhyagarbha tantra’s authenticity, it may be because Śākyaśrībhadra, the Kashmiri guru who taught Sakya Paṇḍita, verified a Sanskrit manuscript of the tantra which had been found at Samyé (this is mentioned in a 12th or 13th century Sakya biography of Śākyaśrībhadra). The manuscript was passed from hand to hand until it reached Gö Lotsawa Zhönu Pal, author of the Blue Annals, who wrote:

When the Great Kashmiri Pandita (Śākyaśrī) arrived at Samyé, he discovered the Sanskrit text of the Guhyagarbha. Later it came into the hands of Tatön Ziji, who presented it to it Shagang Lotsawa. The latter sent the manuscript to Chomden Rigpai Ralgri, who accepted it and composed The Flower to Ornament the Accomplishment of the Guhyagarbha. He showed the text at an assembly of tantrikas at Mamoné, and highly praised it. After that Tarpa Lotsawa made a translation of the Subsequent Guhyagarbha Tantra which had not been found before. Most of the pages of the manuscript were damaged. The remaining pages of the Sanskrit manuscript are in my hands.

So the authenticity of the Guhyagarbha tantra seems to be rather a non-issue, despite all the polemical activity devoted to the question over the centuries in Tibet. Still, some may be interested in the Guhyagarbha-related material that is to be found in the Dunhuang collections. While these manuscripts are alost certainly no earlier than the 10th century, they do provide some insights into the role of the Guhyagarbha in early Tibet:

Some of the sādhanas (manuals for meditation practice) quote the Guhyagarbha, though this is a little inconclusive, since (i) it is difficult to find exact parallel passages in the tantra itself and (ii) the Guhyagarbha is not mentioned by name. See for example IOL Tib J 332, which was originally noticed by Ken Eastman in his article listed below.

One manuscript (IOL Tib J 540) is a list of the mantras and the names of each of the 42 deities from the Guhyagarbha‘s peaceful maṇḍala.

One scroll, which I mentioned in the previous post (Pelliot tibétain 849), contains a list of tantras in Tibetan and Sanskrit. It includes the Guhyagarbha–listed as rgyud gsang ba’I snyIng po in Tibetan and ‘Gu yya kar rba tan tra in Sanskrit (the Sanskrit tranliterations on this scroll are wildly erratic). The scroll is, as I mentioned previously, probably notes from the teachings of an Indian guru who passed through Dunhuang on his way to China. However, it is dated to the very end of the 10th century, so this tells us little about the existence of the tantra in Tibet prior to this time.

Thus something of the Guhyagarbha tantra is there in the manuscripts, but it has a lesser presence than one might expect given its importance in the later Nyingma tradition. What is perhaps most striking is how many more references and quotations from a different tantra, the Guhyasamāja, are found among the manuscripts. The Guhyasamāja tantra itself appears in an almost complete manuscript (IOL Tib J 438), and is quoted more often and by name in various treatises and sādhanas. This raises the question of whether the Guhyasamāja tantra was actually more influential in pre-11th century Tibet than theGuhyagarbha tantra.

Perhaps the attacks on the Guhyagarbha and similar tantras were after all, as the Nyingma apologists suggest, politically motivated. In the struggles between the holders of the old lineages (i.e. the incipient Nyingmapas, the Zur family in particular) and the translators of the newly arrived tantric lineages, the Guhyagarbha was an easy target, as it was not featured in any of the new lineages, unlike the Guhyasamāja. Equally the Nyingmapas seem to have focussed more and more on the Guhyagarbha from the 11th century onward–perhaps exactly because it was not shared with the new schools.

References

1. Dorje, Gyurme. (no date). The Guhyagarbha Tantra: Introduction. Online at the Wisdom Books Reading Room

2. Eastman, Kenneth. 1983. “Mahāyoga Texts at Tun-huang”. Bulletin of the Institute of Cultural Studies, Ryukoku University 22: 42-60.

3. van der Kuijp, Leonard. 1994. “On the Lives of Śākyaśrībhadra (?-?1225)”. Journal of the American Oriental Society 114/4: 599–616. Available on JSTOR.

4. Martin, Dan. 1987. “Illusion Web: Locating the Guhyagarbha Tantra in Buddhist

Intellectual History”. Christopher I. Beckwith (ed.) Silver on Lapis: Tibetan Literary Culture and History. Bloomington: The Tibet Society. 175-220. Available for free download here.

5. Roerich. (trans.) 1949. The Blue Annals. Calcutta: Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal. (See pp.104-5.) Also available here.

6. Stearns, Cyrus. 2001. Luminous Lives. Boston: Wisdom Publications.

7. Wangchuk, Dorji. 2002. “An Eleventh-Century Defence of the Authenticity of the Guhyagarbha Tantra“. In Eimer and Germano (eds), The Many Canons of Tibetan Buddhism. Leiden: Brill.