Difference between revisions of "The Symbolism of the Early Stūpa"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| <poem> by Peter Harvey I. Introduction In this paper, I wish to focus on the symbolism of the Buddhist stiipa. In its sim...") |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

I. Introduction | I. Introduction | ||

| − | In this paper, I wish to focus on the symbolism of the Buddhist stiipa. In its simplest sense, this is a "(relic) mound" and a symbol of the Buddha's parinibbiina. I wish to show, how ever, that its form also comprises a system of overlapping sym bols which make the stupa as a whole into a symbol of the Dhamma and of the enlightened state of a Buddha. | + | In this paper, I wish to focus on the [[symbolism]] of the [[Buddhist]] stiipa. In its simplest [[sense]], this is a "([[relic]]) mound" and a [[symbol]] of the [[Buddha's]] parinibbiina. I wish to show, how ever, that its [[form]] also comprises a system of overlapping sym bols which make the [[stupa]] as a whole into a [[symbol]] of the [[Dhamma]] and of the [[enlightened]] state of a Buddha. |

| − | Some authors, such as John Irwin,1 Ananda Coomaras wamy,and, to some extent, Lama Anagarika Govinda,:have seen a largely pre-Buddhist, Vedic rneaning in the stupa's sym bolism. I wish to bring out its Buddhist meaning, drawing on certain evidence cited by Irwin in support of his interpretation, and on the work of such scholars as Gustav Roth.4 | + | Some authors, such as John Irwin,1 [[Ananda]] Coomaras wamy,and, to some extent, [[Lama]] [[Anagarika]] Govinda,:have seen a largely pre-Buddhist, {{Wiki|Vedic}} rneaning in the stupa's sym bolism. I wish to bring out its [[Buddhist]] meaning, drawing on certain {{Wiki|evidence}} cited by Irwin in support of his interpretation, and on the work of such [[scholars]] as Gustav Roth.4 |

II. The Origins of the Stupa | II. The Origins of the Stupa | ||

| − | From pre-Buddhist times, in India and elsewhere, the re mains of kings and heroes were interred in burial mounds (tu muli), out of both respect and fear of the dead. Those in an cient India were low, circular mounds of earth, kept in place by a ring of boulders; these boulders also served to mark off a mound as a sacred area. | + | From pre-Buddhist [[times]], in [[India]] and elsewhere, the re mains of {{Wiki|kings}} and heroes were interred in burial mounds (tu muli), out of both [[respect]] and {{Wiki|fear}} of the [[dead]]. Those in an cient [[India]] were low, circular mounds of [[earth]], kept in place by a ring of boulders; these boulders also served to mark off a mound as a [[sacred]] area. |

| − | According to the account in the Mahiiparinibbiina Sutta (D.Il.l41-3), when the Buddha was asked what was to be done | + | According to the account in the Mahiiparinibbiina [[Sutta]] (D.Il.l41-3), when the [[Buddha]] was asked what was to be done |

| − | *First given at the Eighth Symposium on Indian Religions (British Association for the History of Religion), Oxford, April | + | *First given at the Eighth Symposium on [[Indian]] [[Religions]] (British Association for the History of [[Religion]]), Oxford, April |

| − | 1982 with his remains after death, he seems to have brought to mind this ancient tradition. He explained that his body should be treated like that of a Cakkavatti emperor: after wrapping it in many layers of cloth and placing it within two iron vessels, it should be cremated; the relics should then be placed in a stupa "where four roads meet" (ciitummahiipathe). The relics of a "dis ciple" (siivaka) of a Tathagata should be treated likewise. At the stupa of either, a person's citta could be gladdened and calmed at the thought of its significance. | + | 1982 with his {{Wiki|remains}} after [[death]], he seems to have brought to [[mind]] this ancient [[tradition]]. He explained that his [[body]] should be treated like that of a [[Cakkavatti]] {{Wiki|emperor}}: after wrapping it in many layers of cloth and placing it within two [[iron]] vessels, it should be {{Wiki|cremated}}; the [[relics]] should then be placed in a [[stupa]] "where four roads meet" (ciitummahiipathe). The [[relics]] of a "dis ciple" (siivaka) of a [[Tathagata]] should be treated likewise. At the [[stupa]] of either, a person's [[citta]] could be gladdened and [[calmed]] at the [[thought]] of its significance. |

[[File:Dciplan3rd.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dciplan3rd.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | After the Buddha's cremation, his relics (sariras) are said to have been divided into eight portions, and each was placed in a stupa. The pot (kumbha) in which the relics were collected and the ashes of the cremation fire were dealt with in the same way (D.I 1.166). | + | After the [[Buddha's]] [[cremation]], his [[relics]] ([[sariras]]) are said to have been divided into eight portions, and each was placed in a [[stupa]]. The pot ([[kumbha]]) in which the [[relics]] were collected and the ashes of the [[cremation]] [[fire]] were dealt with in the same way (D.I 1.166). |

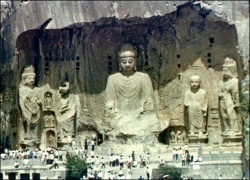

| − | ()ne of the things which Asoka (273-232 B.C.) did in his efforts to spread Buddhism, was to open up these original ten stupas and distribute their relics in thousands of new stupas throughout India. By doing this, the stiipa was greatly popular ised. Though the development of the Buddha-image, probably in the second century A.D., provided another focus for devo tion to the Buddha, stiipas remain popular to this day, especial ly in Theravadin countries. rfhey have gone through a long development in form and symbolism, but I wish to concentrate on their early significance. | + | ()ne of the things which [[Asoka]] (273-232 B.C.) did in his efforts to spread [[Buddhism]], was to open up these original ten [[stupas]] and distribute their [[relics]] in thousands of new [[stupas]] throughout [[India]]. By doing this, the stiipa was greatly popular ised. Though the development of the Buddha-image, probably in the second century A.D., provided another focus for devo tion to the [[Buddha]], stiipas remain popular to this day, especial ly in [[Theravadin]] countries. rfhey have gone through a long development in [[form]] and [[symbolism]], but I wish to [[concentrate]] on their early significance. |

Ill. Relics | Ill. Relics | ||

| − | Before dealing with the stupa itself, it is necessary to say something about the relics contained in it. The contents of a stiipa may be the reputed physical relics (sariras or dhiitus) of Gotama Buddha, of a previous Buddha, of an Arahant or other saint, or copies of these relics; they may also be o jects used by such holy beings, images symbolising them, or texts seen as the "relics" of the "Dhamma-body" of Gotama Buddha. | + | Before dealing with the [[stupa]] itself, it is necessary to say something about the [[relics]] contained in it. The contents of a stiipa may be the reputed [[physical]] [[relics]] ([[sariras]] or dhiitus) of [[Gotama Buddha]], of a previous [[Buddha]], of an [[Arahant]] or other {{Wiki|saint}}, or copies of these [[relics]]; they may also be o jects used by such holy [[beings]], images symbolising them, or texts seen as the "[[relics]]" of the "Dhamma-body" of [[Gotama]] Buddha. |

| − | Physical relics are seen as the most powerful kind of contents. Firstly, they act as reminders of a Buddha or saint: of their spiritual qualities, their teachings, and the fact that they have actually lived on this earth. 'fhis, in turn, shows that it is possible for a human being to become a Buddha or saint. While even copies of relics can act as reminders, they cannot fulfill the second function of relics proper. This is because these are thought to contain something of the spiritual force and purity of the person they once formed part of. As they were part of the body of a person whose mind was freed of spiritual faults and possessed of a great energy-for-good, it is believed that they were somehow affected by this. Relics are therefore seen as radiating a kind of beneficial power. This is probably why ch. | + | Physical [[relics]] are seen as the most powerful kind of contents. Firstly, they act as reminders of a [[Buddha]] or {{Wiki|saint}}: of their [[spiritual]] qualities, their teachings, and the fact that they have actually lived on this [[earth]]. 'fhis, in turn, shows that it is possible for a [[human being]] to become a [[Buddha]] or {{Wiki|saint}}. While even copies of [[relics]] can act as reminders, they cannot fulfill the second [[function]] of [[relics]] proper. This is because these are [[thought]] to contain something of the [[spiritual]] force and [[purity]] of the [[person]] they once formed part of. As they were part of the [[body]] of a [[person]] whose [[mind]] was freed of [[spiritual]] faults and possessed of a great energy-for-good, it is believed that they were somehow affected by this. [[Relics]] are therefore seen as radiating a kind of beneficial [[power]]. This is probably why ch. |

| − | 28 of the Buddhavarpsa says: The ancients say that the dispersal of the relics of Gotama, the great seer, was out of compassion for living beings. | + | 28 of the Buddhavarpsa says: The ancients say that the dispersal of the [[relics]] of [[Gotama]], the great seer, was out of [[compassion]] for living beings. |

[[File:948.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:948.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Miraculous powers are also attributed to relics, as seen in a story of the second century B.C. related in the Mahiiva1{1Sa XXXI v.97-IOO. When king DunhagamaQi was enshrining some relics of Gotama in the Great Stiipa at Anuradhapura, they rose into the air in their casket, and then emerged to form the shape of the Buddha. In a similar vein, the Vibhanga AUha katha p. 433 says that at the end of the 5000 year period of the siisana, all the relics in Sri | + | Miraculous [[powers]] are also attributed to [[relics]], as seen in a story of the second century B.C. related in the Mahiiva1{1Sa XXXI v.97-IOO. When [[king]] DunhagamaQi was enshrining some [[relics]] of [[Gotama]] in the Great Stiipa at [[Anuradhapura]], they rose into the [[air]] in their casket, and then emerged to [[form]] the [[shape]] of the [[Buddha]]. In a similar vein, the [[Vibhanga]] AUha katha p. 433 says that at the end of the 5000 year period of the siisana, all the [[relics]] in [[Sri Lanka]] will assemble, travel through the [[air]] to the foot of the [[Bodhi tree]] in [[India]], emit rays of [[light]], and then disappear in a flash of [[light]]. l his is referred to as the parinibbiina of the dhiitus. [[Relics]], then, act both as reminders of [[Gotama]], or some other holy [[being]], and as actual tangible links with them and their [[spiritual]] [[powers]]. The Mahava1{1Sa XXX v.1 00 says, indeed, that there is equal [[merit]] in devotion to the [[Buddha's relics]] as there was in devotion to him when he was alive. |

| − | IV. The Symbolism of the Stiipa's Components | + | IV. The [[Symbolism]] of the Stiipa's Components |

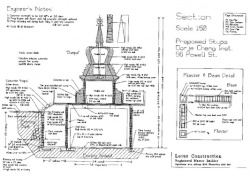

| − | The best preserved of the early Indian stupas is the Great Stiipa at Saflci, central India. First built by Asoka, it was later enlarged and embellished, up to the first century A.D. The diagramatic representation of it in figure I gives a clear indica tion of the various parts of an early stu pa. | + | The best preserved of the early [[Indian]] [[stupas]] is the Great Stiipa at Saflci, central [[India]]. First built by [[Asoka]], it was later enlarged and embellished, up to the first century A.D. The diagramatic [[representation]] of it in figure I gives a clear indica tion of the various parts of an early stu pa. |

| − | The four torarJa.5, or gateways, of this stupa were built between the first centuries B.C. and A.D., to replace previous wooden ones. Their presence puts the stflpa, symbolically, at the place where four roads meet, as is specified in the Mahapar inibbflna Sutta. This is probably to indicate the openness and universality of the Buddhist teaching, which invites all to come and try its path, and also to radiate loving-kindness to beings in all four directions. | + | The four torarJa.5, or gateways, of this [[stupa]] were built between the first centuries B.C. and A.D., to replace previous wooden ones. Their presence puts the stflpa, [[symbolically]], at the place where four roads meet, as is specified in the Mahapar inibbflna [[Sutta]]. This is probably to indicate the [[openness]] and universality of the [[Buddhist teaching]], which invites all to come and try its [[path]], and also to radiate [[loving-kindness]] to [[beings]] in all four directions. |

| − | In a later development of the stiipa, in North India, the orientation to the four directions was often expressed by n1eans of a square, terraced base, sornetimes with staircases on each side in place of the early gateways. At Sand, these gateways arc covered with carved reliefs of the Bodhisatta career of Gotarna and also, using aniconic syrnbols, of his final life as a Buddha. Symbols also represent previous Buddhas. In this way, the gates convey Buddhist teachings and the life of the Buddhas to those who enter the precincts of the stflpa. | + | In a later development of the stiipa, in {{Wiki|North}} [[India]], the orientation to the four [[directions]] was often expressed by n1eans of a square, terraced base, sornetimes with staircases on each side in place of the early gateways. At Sand, these gateways arc covered with carved reliefs of the [[Bodhisatta]] career of Gotarna and also, using aniconic syrnbols, of his final [[life]] as a [[Buddha]]. [[Symbols]] also represent previous [[Buddhas]]. In this way, the gates convey [[Buddhist teachings]] and the [[life]] of the [[Buddhas]] to those who enter the precincts of the stflpa. |

| − | :ncircling Sand stupa, connecting its gateways, is a stone vedikii, or railing, originally made of wood. This encloses and marks off the site dedicated to the stupa and a path for circu marnbulating it. Clockwise circun1an1bulation, or padakkhi tiil prada irJii, literally "keeping to the right," is the n1ain act of devotion performed at a stu pa. It is also performed round a Bodhi | + | :ncircling Sand [[stupa]], connecting its gateways, is a stone vedikii, or railing, originally made of [[wood]]. This encloses and [[marks]] off the site dedicated to the [[stupa]] and a [[path]] for circu marnbulating it. Clockwise circun1an1bulation, or padakkhi tiil prada irJii, literally "keeping to the [[right]]," is the n1ain act of devotion performed at a stu pa. It is also performed round a [[Bodhi tree]] and, especially in [[Tibet]], round any [[sacred]] o ject, building or [[person]]. Keeping one's [[right]] side towards someone is a way of showing [[respect]] to then1: in the [[Pali Canon]], [[people]] are often said to have departed fron1 the [[Buddha]] keeping their [[right]] side towards hitn. The precedent for actual circumanlbu lation may bave been the Brahrnanical practice of the priest walking around the fire-sacrifice [[offerings]], or of a bride walk ing around the domestic hearth at her rnarriageJi All such prac tices demonstrate that what is walked around is, or should be, the "centre" of a person's life. |

[[File:968.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:968.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Fron1 the main circun1arnbulatory path at Sand, a devotee can tnount sorne stairs to a second one, also enclosed by a ve dik(l. This second path runs round the top of the low cylindrical drurn of the stupa base. •rhe Divylivadiina refers to this as the rnedhi, or platfonn, while sorne n1odern Sinhalese sources refer to it as the iisarw, or throne. This structure serves to elevate the n1ain body of the stflpa, and so put it in a place of honour. In later stf1pas, it was multiplied into a series of terraces, to raise the stupa dome to a yet rnore honourific height. •rhese terraces were probably what developed into the multiple rooves of the East | + | Fron1 the main circun1arnbulatory [[path]] at Sand, a devotee can tnount sorne stairs to a second one, also enclosed by a ve dik(l. This second [[path]] runs round the top of the low cylindrical drurn of the [[stupa]] base. •rhe Divylivadiina refers to this as the rnedhi, or platfonn, while sorne n1odern {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} sources refer to it as the iisarw, or throne. This structure serves to elevate the n1ain [[body]] of the stflpa, and so put it in a place of honour. In later stf1pas, it was multiplied into a series of terraces, to raise the [[stupa]] dome to a yet rnore honourific height. •rhese terraces were probably what developed into the multiple rooves of the {{Wiki|East Asian}} [[form]] of the [[stupa]], often known in the {{Wiki|West}} as a pagoda. |

| − | The most obvious component of the stupa is the solid dome, resting on the base. Its function is to house the precious relics within (the Burmese say that the presence of relics gives a stupa a "heart"). The relics are kept in a relic-chamber, usually somewhere on the central axis of the dome. In this, they are often found to rest in a golden container, placed within a silver, then bronze, then earthenware ones. rrhe casing of the stupa dome seems therefore to be seen as the outermost and least valuable container of the relics. Indeed, the usual term for the dome of a stupa, both in the Sinhalese tradition and in two first century A.D. Sanskrit texts, translated from their Tibetan ver sions by Gustav Roth,6 is kumbha, or pot. The Sanskrit Mahiipar iniroii?Ja Siitra also reports the Buddha as saying that his relics should be placed in a golden kumbha,7 while the P ili Mahiipari nibbiina Sutta says that the Buddha's relics were collected in a kumbha before being divided up. Again, kumbha is used as a word for an urn in which the bones of a dead person arc col lected, in the Brahmanical A.{valilyana Grhya-Siitra. These facts reinforce the idea of the stiipa dome being seen as the outer most container of the relics. | + | The most obvious component of the [[stupa]] is the solid dome, resting on the base. Its [[function]] is to house the [[precious]] [[relics]] within (the [[Burmese]] say that the presence of [[relics]] gives a [[stupa]] a "[[heart]]"). The [[relics]] are kept in a relic-chamber, usually somewhere on the central axis of the dome. In this, they are often found to rest in a golden container, placed within a silver, then bronze, then earthenware ones. rrhe casing of the [[stupa]] dome seems therefore to be seen as the outermost and least valuable container of the [[relics]]. Indeed, the usual term for the dome of a [[stupa]], both in the {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} [[tradition]] and in two first century A.D. [[Sanskrit]] texts, translated from their [[Tibetan]] ver sions by Gustav Roth,6 is [[kumbha]], or pot. The [[Sanskrit]] Mahiipar iniroii?Ja Siitra also reports the [[Buddha]] as saying that his [[relics]] should be placed in a golden kumbha,7 while the P ili Mahiipari nibbiina [[Sutta]] says that the [[Buddha's relics]] were collected in a [[kumbha]] before [[being]] divided up. Again, [[kumbha]] is used as a [[word]] for an urn in which the bones of a [[dead]] [[person]] arc col lected, in the {{Wiki|Brahmanical}} A.{valilyana Grhya-Siitra. These facts reinforce the [[idea]] of the stiipa dome [[being]] seen as the outer most container of the relics. |

[[File:Borobudur012.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Borobudur012.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The dome of the stftpa is a "kumbha" not only as a relic pot, but also because of symbolic connotations of the word kurnhha. At S.ll.83, it is said that the death of an Arahant, when feelings "grow cold" and sariras remain, is like the cooling off of a kumbha taken fron1 an oven, with kapalliini rernaining. Wood ward's translation gives "sherds" for this, but the Rhys Davids and Stede Pali-English Dictionary gives "a bowl in the form of a sku}) ... an earthenware pan used to carry ashes." The itnplica tion of the cited passage would seem to be that a (cold) kumhha is itself like the relics of a saint; certainly Dhp. v.40 sees the body (krlya) as like a kumbha (in its fragility, says the con1n1entary). Thus, the stupa don1e both is a container of the relics, and also an analogical representative of the relics. | + | The dome of the stftpa is a "[[kumbha]]" not only as a [[relic]] pot, but also because of [[symbolic]] connotations of the [[word]] kurnhha. At S.ll.83, it is said that the [[death]] of an [[Arahant]], when [[feelings]] "grow cold" and [[sariras]] remain, is like the cooling off of a [[kumbha]] taken fron1 an oven, with kapalliini rernaining. Wood ward's translation gives "sherds" for this, but the Rhys Davids and Stede Pali-English {{Wiki|Dictionary}} gives "a [[bowl]] in the [[form]] of a sku}) ... an earthenware pan used to carry ashes." The itnplica tion of the cited passage would seem to be that a (cold) kumhha is itself like the [[relics]] of a {{Wiki|saint}}; certainly Dhp. v.40 sees the [[body]] (krlya) as like a [[kumbha]] (in its fragility, says the con1n1entary). Thus, the [[stupa]] don1e both is a container of the [[relics]], and also an analogical representative of the relics. |

| − | 'I'he use of the tern1 kumhha for the stiipa dome n1ay well have further symbolic meaning. It rnay relate to the pur w-gha(a (or fJilrrJa-kumbha), or vase of plenty. This is one of the eight auspicious symbols in the Sinhalese and Tibetan traditions, and is found as a decoration in ancient Indian Buddhist art. Piir w gha(a designs, for exam pie, were among those on the dome of the Great Stupa at An1aravatiY The pur w-glwa is also an auspi cious symbol in Hinduism, where it is probably equivalent to the golden kumhha, containing amrta (the gods' nectar of im mortality), which emerged at the churning of the cosmic ocean. | + | 'I'he use of the tern1 kumhha for the stiipa dome n1ay well have further [[symbolic]] meaning. It rnay relate to the pur w-gha(a (or fJilrrJa-kumbha), or vase of plenty. This is one of the [[eight auspicious symbols]] in the {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} and [[Tibetan]] [[traditions]], and is found as a decoration in ancient [[Indian]] [[Buddhist]] [[art]]. Piir w gha(a designs, for exam pie, were among those on the dome of the Great [[Stupa]] at An1aravatiY The pur w-glwa is also an auspi cious [[symbol]] in [[Hinduism]], where it is probably equivalent to the golden kumhha, containing amrta (the [[gods]]' [[nectar]] of im mortality), which emerged at the churning of the [[cosmic]] ocean. |

| − | To decide on the symbolic meanings of kumhha in Buddhism, we may fruitfully look at further uses of the word kumbha in sulta sin1ilies. At S.V.48 and A.V.3: 7, water pouring out from an upturned kumbha is likened to an ariyan disciple getting rid of unskilful states, while at Dhp. v.121-2, a kumbha being gradually filled by drops of water is likened to a person gradually tilling himself with evil or merit. In this way, the kumbha is generally likened to the personality as a container of bad or good states. A number of passages, though, use a full kumbha as a sin1ile for a specifically positive state | + | To decide on the [[symbolic]] meanings of kumhha in [[Buddhism]], we may fruitfully look at further uses of the [[word]] [[kumbha]] in sulta sin1ilies. At S.V.48 and A.V.3: 7, [[water]] pouring out from an upturned [[kumbha]] is likened to an [[ariyan]] [[disciple]] getting rid of unskilful states, while at Dhp. v.121-2, a [[kumbha]] [[being]] gradually filled by drops of [[water]] is likened to a [[person]] gradually tilling himself with [[evil]] or [[merit]]. In this way, the [[kumbha]] is generally likened to the [[personality]] as a container of bad or good states. A number of passages, though, use a full [[kumbha]] as a sin1ile for a specifically positive [[state of being]]. At A.I1.1 04, a [[person]] who [[understands]], as they really are, the four [[ariyan]] [[truths]], is like a full (puro)kumbha. Miln.414, with Sn. v. 721-2, sees one who has perfected his recluseship (an [[Arahant]], surely) as [[being]] like a full kumhha, which makes no [[sound]] when struck: his [[speech]] is not boastful, but he teaches Dhamn1a. At A.l.131, a [[person]] of wide wisdorn (puthupariiio), who bears in n1ind the [[Dhamma]] he has [[heard]], is like an upright [[kumbha]] which accurnulates the [[water]] poured into it. The itnplication of these passages is that the stflpa dome, if known as a [[kumbha]] and even decorated with pur ta-gha(a motifs, would be a natural [[symbol]] for the [[personality]] of someone who is "full" of Dhan1n1a: a [[Buddha]] or {{Wiki|saint}}. While the [[Hindu]] piirtta-gha(a con tains amrta, the [[Buddhist]] one contains Dhamrna, that which brings a [[person]] to the [[amata]] and which in the [[highest]] [[sense]] ([[Nibbana]]) is this "deathless" state. |

[[File:Boudhanath Stupa 456.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Boudhanath Stupa 456.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The above symbolisJn neatly dove-tails with another indica tion of the dome's meaning. As stu pas developed, they sotne times can1e to have interior strengthening walls radiating- from the centre, as in figure 2. As the stiipa dome, in plan, is circular, the impression is strongly given of the Dhamma-wheel syn1bol. This sytnbolises both the Buddha and the Dhan1ma-teaching, path and culmination-in a number of ways. For cxarnple, i) its regularly spaced spokes suggest the spiritual order and rnental integration produced in one who practices Dhan1ma; ii) as the spokes converge in the hub, so the factors of Dhamma, in the sense of the path, lead to Dhamma, in the sense of Nibbana; iii) as the spokes stand firm in the hub, so the Buddha was the discoverer and teacher of the Dhamma: he firmly established its practice in the world. The Dhamma-wheel is also a symbol of universal spiritual sovereignty, which aligns with the signifi cance of the stiipa's openness to the four directions (see above). | + | The above symbolisJn neatly dove-tails with another indica tion of the dome's meaning. As stu pas developed, they sotne [[times]] can1e to have interior strengthening walls radiating- from the centre, as in figure 2. As the stiipa dome, in plan, is circular, the [[impression]] is strongly given of the Dhamma-wheel syn1bol. This sytnbolises both the [[Buddha]] and the Dhan1ma-teaching, [[path]] and culmination-in a number of ways. For cxarnple, i) its regularly spaced spokes suggest the [[spiritual]] [[order]] and rnental integration produced in one who practices Dhan1ma; ii) as the spokes converge in the hub, so the factors of [[Dhamma]], in the [[sense]] of the [[path]], lead to [[Dhamma]], in the [[sense]] of [[Nibbana]]; iii) as the spokes stand firm in the hub, so the [[Buddha]] was the discoverer and [[teacher]] of the [[Dhamma]]: he firmly established its practice in the [[world]]. The Dhamma-wheel is also a [[symbol]] of [[universal]] [[spiritual]] sovereignty, which aligns with the signifi cance of the stiipa's [[openness]] to the four [[directions]] (see above). |

| − | The stiipa dome, then, is not only a container of the Bud dha's relics and their power, but also sytnbolises both the state of the Buddha, and the Dhamma he encotnpassed. The dome is also known, in the third century A.D. Divyiivadiina, as the ar:uf,a, or egg. The meaning of this must be that, just as an egg contains the potential for growth, so the stiipa dome contains relics, sometimes known as bijas, or seeds. By devotion to the stiipa and its relics, a person's spiritual life may grow and be fruitful. This connotation is a neat parallel to that of the dome as a "vase of plenty." | + | The stiipa dome, then, is not only a container of the Bud dha's [[relics]] and their [[power]], but also sytnbolises both the state of the [[Buddha]], and the [[Dhamma]] he encotnpassed. The dome is also known, in the third century A.D. Divyiivadiina, as the ar:uf,a, or egg. The meaning of this must be that, just as an egg contains the potential for growth, so the stiipa dome contains [[relics]], sometimes known as bijas, or [[seeds]]. By devotion to the stiipa and its [[relics]], a person's [[spiritual]] [[life]] may grow and be fruitful. This connotation is a neat parallel to that of the dome as a "vase of plenty." |

| − | Another connection with spiritual growth is provided by the association of the stiipa dome with the lotus (which, inci dentally, is often portrayed growing out of a purr.w-gha(a). Do1nes are often decorated with lotus designs, and their circu lar plans resemble the circle of an open lotus | + | Another connection with [[spiritual]] growth is provided by the association of the stiipa dome with the [[lotus]] (which, inci dentally, is often portrayed growing out of a purr.w-gha(a). Do1nes are often decorated with [[lotus]] designs, and their circu lar plans resemble the circle of an open [[lotus flower]], as in the lotus-medallion shown in figure 3. In addition, the [[Burmese]] see the [[shape]] of the stiipa (whose bulk is its dome) as that of a [[lotus]] bud, with the [[name]] of its components recalling the [[idea]] of a [[flower]] bud with its young leaves folded in adoration. 11 We see, then, that a further [[Buddhist]] [[symbol]] is included in the stiipa as a symbol-system. |

| − | The lotus, of course, is a common Buddhist symbol from early times. While it is a popular pan-Indian symbol for birth, its meaning in Buddhism is best given by a passage frequently recurring in the suttas (e.g., S.III.l40): | + | The [[lotus]], of course, is a common [[Buddhist]] [[symbol]] from early [[times]]. While it is a popular pan-Indian [[symbol]] for [[birth]], its meaning in [[Buddhism]] is best given by a passage frequently recurring in the [[suttas]] (e.g., S.III.l40): |

| − | "Just as, monks, a lotus, blue, red, or white, though born in the water, grown up in the water, when it reaches the sur face stands unsoiled by the water; just so, monks, though born in the world, grown up in the world, having over come the world, a Tathagata abides unsoiled by the world." | + | "Just as, [[monks]], a [[lotus]], [[blue]], red, or white, though born in the [[water]], grown up in the [[water]], when it reaches the sur face stands unsoiled by the [[water]]; just so, [[monks]], though born in the [[world]], grown up in the [[world]], having over come the [[world]], a [[Tathagata]] abides unsoiled by the world." |

[[File:Dia 0079.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dia 0079.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Just as the beautiful lotus blossom grows up from the mud and water, so one with an enlightened rnind, a Buddha, develops out of the ranks of ordinary beings, by maturing, over many lives, the spiritual potential latent in all. He thus stands out above the greed, hatred and delusion of the world, not attached to anything, as a lotus | + | Just as the [[beautiful]] [[lotus]] blossom grows up from the mud and [[water]], so one with an [[enlightened]] rnind, a [[Buddha]], develops out of the ranks of ordinary [[beings]], by maturing, over many [[lives]], the [[spiritual]] potential latent in all. He thus stands out above the [[greed]], [[hatred]] and [[delusion]] of the [[world]], not attached to anything, as a [[lotus flower]] stands above the [[water]], unsoiled by it. The [[lotus]], then, syn1bolises the potential for [[spiritual]] growth latent in all [[beings]], and the complete non-attachtnent of the [[enlightened]] n1ind, which stands beyond all defilements. |

| − | Not only are the Dhanuna-whcel and lotus syn1bols incorporated within the stupa but, as we shall now see, the other key syrnbol, the Bodhi | + | Not only are the Dhanuna-whcel and [[lotus]] syn1bols incorporated within the [[stupa]] but, as we shall now see, the other key syrnbol, the [[Bodhi tree]], also finds a place in this symbol-systcrn. ()n top of Sai1d [[stupa]] can be seen a ya. i, or pole, with three discs on it (figure I). These discs represent cerernonial [[parasols]], the ancient [[Indian]] ernblen1s of royalty. Large ceretnonial para sols are still used in South-East {{Wiki|Asia}}, for exatnple to hold over a n1an about to be [[ordained]], i.e., over someone in a role parallel to that of [[prince]] [[Siddhattha]]. In [[Tibetan]] Buddhisrn, such para sols arc held over the [[Dalai]] Lan1a on in1portant occasions. By placing [[parasols]] on a [[stupa]], there is expressed the [[idea]] of the [[spiritual]] sovereignty of the [[Buddha]] and his teachings (also ex pressed by the Dhan1n1a-wheel syrnbol). In accordance with this interpretation of a stupa's pole and discs, we see that [[king]] DunhagatnatJi of [[Sri Lanka]] (second century B.C.), when he had finished the Great [[Stupa]] at [[Anuradhapura]], placed his roy al [[parasol]] on it, conferring on it sovereignty over [[Sri Lanka]] for seven days (Mahflvayttsa XXXI v. 90 and Ill); he later replaced his [[parasol]] with a [[wood]] or stone copy. |

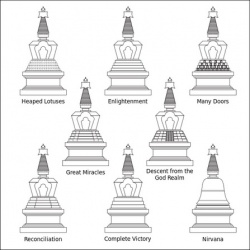

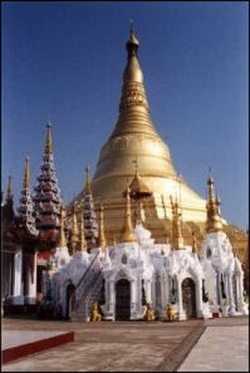

| − | While there are three honourific parasol-discs at Sar1d, on later stiipas these generally increased in nurnber, so as to in crease the inferred honour. 12 Sometin1es, they came to fuse into a spire, as seen in the present super-structure of the Great Stupa at Anuradhapura (figure 4). Another phase in the devel opnlent of a spire can be seen in the 14-16th century Shwe Dagon Stupa in Rangoon (figure 5). Here, the don1c is bell shaped and has come to merge with the spire, to forrn one flowing outline. Because the spire no longer really conveys the impression of a series of parasol-discs, a separate, large n1ctal parasol is placed at its sun1mit. | + | While there are three honourific parasol-discs at Sar1d, on later stiipas these generally increased in nurnber, so as to in crease the inferred honour. 12 Sometin1es, they came to fuse into a spire, as seen in the present super-structure of the Great [[Stupa]] at [[Anuradhapura]] (figure 4). Another phase in the devel opnlent of a spire can be seen in the 14-16th century Shwe Dagon [[Stupa]] in {{Wiki|Rangoon}} (figure 5). Here, the don1c is bell shaped and has come to merge with the spire, to forrn one flowing outline. Because the spire no longer really conveys the [[impression]] of a series of parasol-discs, a separate, large n1ctal [[parasol]] is placed at its sun1mit. |

| − | The use of the parasol as an e1nblen1 of royalty probably derives from the ancient custorn of a ruler sitting under the shade of a sacred tree, at the centre of a comn1unity, to ad ministerjustice. The shading tree thus becarne an insignia of sover eignty. When the ruler rnoved about, it carne t.o be represented by a parasol. The parasols on a stupa, then, while being an en1blern of sovereignty, alw connote a sacred tree. Indeed, a second century B.C. relief from Amaravati depicts a stupa which, in place of the ya. {i and parasol discs, has a tree with parasol-shaped leaves . | + | The use of the [[parasol]] as an e1nblen1 of royalty probably derives from the ancient custorn of a ruler sitting under the shade of a [[sacred]] [[tree]], at the centre of a comn1unity, to ad ministerjustice. The shading [[tree]] thus becarne an insignia of sover eignty. When the ruler rnoved about, it carne t.o be represented by a [[parasol]]. The [[parasols]] on a [[stupa]], then, while [[being]] an en1blern of sovereignty, alw connote a [[sacred]] [[tree]]. Indeed, a second century B.C. relief from {{Wiki|Amaravati}} depicts a [[stupa]] which, in place of the ya. {i and [[parasol]] discs, has a [[tree]] with parasol-shaped leaves . |

[[File:Dongzhng.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dongzhng.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | ()f course, the Buddhist sacred tree is the Bodhi | + | ()f course, the [[Buddhist]] [[sacred]] [[tree]] is the [[Bodhi tree]], J: so the ya.i and [[parasols]] on a [[stupa]] Inust syn1bolically represent this, itself a potent [[Buddhist]] syrnbol. This [[idea]] is re-inforced by the fact that, in [[Burma]], free-standing [[parasols]] are sornetin1es worshipped as [[Bodhi tree]] [[symbols]], and the n1etal [[parasols]] on [[stupas]] sometimes have srnall brass [[Bodhi]] leaves hanging frorn them. That the ya.i and parasol-discs represent a [[Bodhi tree]] is also supported when we examine the structure in1mediately below them on a [[stupa]]. Figure l shows that, at Sand, this is a cubical stone, surrounded by another vedikrl, or railing. |

| − | Now these two features are reminiscent of ones found at pre-Bud dhist tree-shrines, which had an altar-seat at their base, and a railing to surround their sacred enclosure. In Buddhisrn, de scendants of the original Bod hi tree became o jects of devotion f(lf, as in the case of physical relics, they were a tangible link with the departed Buddha and his spiritual power. Such Bodhi trees were enclosed by railings in the same way as the previous tree shrines. As the style of the stupa developed, the cubical stone structure expanded in size and can1e to incorporate the vedikii in the fonn of a carved relief on its surface, as in figure 4. The irnportant point to note is that Bodhi | + | Now these two {{Wiki|features}} are reminiscent of ones found at pre-Bud dhist tree-shrines, which had an altar-seat at their base, and a railing to surround their [[sacred]] enclosure. In Buddhisrn, de scendants of the original Bod hi [[tree]] became o jects of devotion f(lf, as in the case of [[physical]] [[relics]], they were a tangible link with the departed [[Buddha]] and his [[spiritual]] [[power]]. Such [[Bodhi trees]] were enclosed by railings in the same way as the previous [[tree]] [[shrines]]. As the style of the [[stupa]] developed, the cubical stone structure expanded in size and can1e to incorporate the vedikii in the fonn of a carved relief on its surface, as in figure 4. The irnportant point to note is that [[Bodhi tree]] [[shrines]] devel oped into n1ore cornplex [[forms]], as seen for [[example]] in figure 7; as this happened, the superstructure of [[stupas]] tnirrored this development, as seen in figure 8. This is dear {{Wiki|evidence}} that the superstructure of a [[stupa]] was syrnbolically equated with a [[Bodhi tree]] and its shrine. |

| − | The Bodhi | + | The [[Bodhi tree]], of course, as the kind of [[tree]] under which the [[Buddha]] attained enlightenrnent, became established as a syn1bol for that enlightenrnent, in early Buddhisrn.H Like the [[lotus]], it is a syrnbol drawn from the vegetable {{Wiki|kingdom}}. While both, therefore, suggest [[spiritual]] growth, the [[lotus]] emphasizes the potential for growth, whereas the [[Bodhi tree]] indicates the culmination of this growth, enlightenn1ent. |

| − | The structure underneath the royal/Bodhi tree syrnbol came to be known, e.g., in the Dirryiivadiina, as the harmikii, or "top enclosure." This was the name for a cool sumtner chatnber on the roof of a building. This connection need not contradict the idea of the structure as a symbolic Bodhi | + | The structure underneath the royal/Bodhi [[tree]] syrnbol came to be known, e.g., in the Dirryiivadiina, as the harmikii, or "top enclosure." This was the [[name]] for a cool sumtner chatnber on the roof of a building. This connection need not contradict the [[idea]] of the structure as a [[symbolic]] [[Bodhi tree]] [[shrine]], for both a cool "top enclosure" and a [[Bodhi tree]] can symbolise the [[enlightened]] [[mind]]: the chamber suggests its "coolness," and the [[tree]] suggests its [[enlightened]] nature. |

[[File:Eight great stupas.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Eight great stupas.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | While all the components of the stupa seem now to have been discussed, there rernains one of crucial irnportance: the axial pillar running down the centre of the dome. This is hid den in most stupas, but it can be seen in the stupa shown in figure 9. John Irwin has reported the finding of axis holes in early stupas, some containing fragments of a wooden axis pole. 15 In the case of the Lauriya-Nandagarh Stiipa (excavated 1904-5), he reports the finding of a waterlogged wooden axis stump, penetrating deep below the original ground-level. Irwin regards this stupa as a very ancient one, pre-third century B.C., but S.P. Gupta argues against this. 11i In the most ancient stupas known (fourth-fifth centuries B.C.), Vaisali and Piprahwa, we find, respectively, only a pile of earth and a pile of rnud faced with mud bricks. They had no axial pole or shaft. Irwin's evi dence, however, is well marshalled, and shows that a wooden axis pole had become incorporated in Buddhist stiipas by the third-second centuries B.C.; S. Paranavitana also has found evidence of what can only have been stone axial pillars in the ruins of early Sinhalese stu pas. | + | While all the components of the [[stupa]] seem now to have been discussed, there rernains one of crucial irnportance: the axial pillar running down the centre of the dome. This is hid den in most [[stupas]], but it can be seen in the [[stupa]] shown in figure 9. John Irwin has reported the finding of axis holes in early [[stupas]], some containing fragments of a wooden axis pole. 15 In the case of the Lauriya-Nandagarh Stiipa (excavated 1904-5), he reports the finding of a waterlogged wooden axis stump, penetrating deep below the original ground-level. Irwin regards this [[stupa]] as a very ancient one, pre-third century B.C., but S.P. Gupta argues against this. 11i In the most ancient [[stupas]] known (fourth-fifth centuries B.C.), [[Vaisali]] and [[Piprahwa]], we find, respectively, only a pile of [[earth]] and a pile of rnud faced with mud bricks. They had no axial pole or shaft. Irwin's evi dence, however, is well marshalled, and shows that a wooden axis pole had become incorporated in [[Buddhist]] stiipas by the third-second centuries B.C.; S. Paranavitana also has found {{Wiki|evidence}} of what can only have been stone axial pillars in the ruins of early {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} stu pas. |

| − | 17 Axial pillars were also a very in1portant feature of East Asian "pagodas," as shown in figure | + | 17 Axial pillars were also a very in1portant feature of {{Wiki|East Asian}} "[[pagodas]]," as shown in figure |

| − | 10. The pagoda form probably developed from a late form of the Indian stupa and certain multi-rooved Chinese buildings. It is important to note, though, that none of the pre-Buddhist Chinese precursors had an axial pillar: this must have derived from the Indian stupa, therefore.'Hyrhe archaeological evidence, then, indicates that in early Indian stupas, after the most ancient period, wooden axial pil lars were incorporated, and that in later ones, they were super seded by stone pillars. Originally, they projected above the stiipa dome, with the ya.yti and parasols as separate items, as in the case of the Amaravati Stupa (dating from Asokan times) shown in figure 9. When, however, the domes of stiipas came to be enlarged, the axes became completely buried within, and the ya tis were fixed on top of them, as if being their extensions. | + | 10. The [[pagoda]] [[form]] probably developed from a late [[form]] of the [[Indian]] [[stupa]] and certain multi-rooved [[Chinese]] buildings. It is important to note, though, that none of the pre-Buddhist [[Chinese]] precursors had an axial pillar: this must have derived from the [[Indian]] [[stupa]], therefore.'Hyrhe {{Wiki|archaeological}} {{Wiki|evidence}}, then, indicates that in early [[Indian]] [[stupas]], after the most ancient period, wooden axial pil lars were incorporated, and that in later ones, they were super seded by stone pillars. Originally, they projected above the stiipa dome, with the ya.yti and [[parasols]] as separate items, as in the case of the {{Wiki|Amaravati}} [[Stupa]] (dating from Asokan [[times]]) shown in figure 9. When, however, the domes of stiipas came to be enlarged, the axes became completely buried within, and the ya tis were fixed on top of them, as if [[being]] their extensions. |

| − | The Divyiivadiina refers to a "yupa-y {i" being implanted in the summit of an enlarged stupa. 1 Y This, and other references, shows that the usual term for the axial pillar of a stiipa was yupa. Somewhat surprisingly, this was the term for the wooden post where, in Vedic religion, an animal would be tethered before it was sacrificed to the gods. There is a parallel in more than name, however. T'he Vedic yupa was square at the bottom, octangular in the middle, and round at the top, while the stone axial pillars of ancient Sinhalese stiipas are found to be of the same basic shape.° Clearly, then, the axial pillars of stiipas had close associations with the Vedic sacrificial post. | + | The Divyiivadiina refers to a "yupa-y {i" [[being]] implanted in the summit of an enlarged [[stupa]]. [[1]] Y This, and other references, shows that the usual term for the axial pillar of a stiipa was yupa. Somewhat surprisingly, this was the term for the wooden post where, in {{Wiki|Vedic}} [[religion]], an [[animal]] would be tethered before it was sacrificed to the [[gods]]. There is a parallel in more than [[name]], however. T'he {{Wiki|Vedic}} yupa was square at the bottom, octangular in the middle, and round at the top, while the stone axial pillars of ancient {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} stiipas are found to be of the same basic shape.° Clearly, then, the axial pillars of stiipas had close associations with the {{Wiki|Vedic}} sacrificial post. |

[[File:Golden-sand-stupa-3.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Golden-sand-stupa-3.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | How can this be explained? While the non-violent teachings of Buddhism r jected animal sacrifice, early Buddhist stiipas may well have been built round Vedic sacrificial posts by converted Brahmins. Indeed, excavation of the early Gotihawa Stiipa, by which Asoka placed a pillar, has revealed animal bones below the original ground level at the base of the stiipa axis, where a wooden post once stood. The most ancient stupas lack signs of any axial pillar, probably because Buddhism was not sufficient ly well established in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. for the conversion of a Brahmanic site to have been acceptable. With the increasing popularity of Buddhism, it would have con1e to be acceptable for stiipas to be built around existing Vedic yupas. These already marked sacred spots of sorts: building stu pas on these spots showed that they were now taken over by the new religion. In such early stiipas, the original wooden Vedic yupa was probably retained to form the stiipa axis, but later on, a stone yupa would have been erected to 1nark the sacred spot which would be the centre of a new stiipa. | + | How can this be explained? While the non-violent teachings of [[Buddhism]] r jected [[animal]] sacrifice, early [[Buddhist]] stiipas may well have been built round {{Wiki|Vedic}} sacrificial posts by converted [[Brahmins]]. Indeed, excavation of the early Gotihawa Stiipa, by which [[Asoka]] placed a pillar, has revealed [[animal]] bones below the original [[ground]] level at the base of the stiipa axis, where a wooden post once stood. The most ancient [[stupas]] lack signs of any axial pillar, probably because [[Buddhism]] was not sufficient ly well established in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. for the [[conversion]] of a [[Brahmanic]] site to have been acceptable. With the increasing popularity of [[Buddhism]], it would have con1e to be acceptable for stiipas to be built around [[existing]] {{Wiki|Vedic}} yupas. These already marked [[sacred]] spots of sorts: building stu pas on these spots showed that they were now taken over by the new [[religion]]. In such early stiipas, the original wooden {{Wiki|Vedic}} yupa was probably retained to [[form]] the stiipa axis, but later on, a stone yupa would have been erected to 1nark the [[sacred]] spot which would be the centre of a new stiipa. |

| − | l he axial yupa of a stupa surely had a further symbolic function. l"'o fully explore this, it is also necessary to note an alternative name for the stupa axis. Paranarvitana has reported that the monks of Sri Lanka (in the 1940s) gave the traditional term for the stOpa axis as Inda-khila, equivalent to the Sanskrit Indra-kila, Indra's stake. 1 The monks did not know the reason for this name, however. John Irwin has argued that both the terms yupa and Indra-kila show the stOpa axis to symbolise the axis mundi: the world pillar or world tree of Vedic mythology. | + | l he axial yupa of a [[stupa]] surely had a further [[symbolic]] [[function]]. l"'o fully explore this, it is also necessary to note an alternative [[name]] for the [[stupa]] axis. Paranarvitana has reported that the [[monks]] of [[Sri Lanka]] (in the 1940s) gave the [[traditional]] term for the stOpa axis as Inda-khila, equivalent to the [[Sanskrit]] Indra-kila, Indra's stake. [[1]] The [[monks]] did not know the [[reason]] for this [[name]], however. John Irwin has argued that both the terms yupa and Indra-kila show the stOpa axis to symbolise the axis mundi: the [[world]] pillar or [[world]] [[tree]] of {{Wiki|Vedic}} mythology. |

| − | I shall summarise Irwin's arguments below before going on to my own preferred interpretation. Firstly, he argues that the Vedic sacrificial yiipa was itself a substitute for the axial world | + | I shall summarise Irwin's arguments below before going on to my own preferred interpretation. Firstly, he argues that the {{Wiki|Vedic}} sacrificial yiipa was itself a substitute for the axial world |

Gyantse0.jpg | Gyantse0.jpg | ||

| − | tree, as demonstrated by the way it is addressed in Brahn1anic texts, and the fact that the tree sections of the yupa (square, octagonal and round) are regarded as representing, respective ly, the earth, the atmosphere, and the heavens.2:-\ Secondly, Irwin notes that "Indra's stake" is the designation, in the Vedas, f(n the stake with which Indra pegged the primaeval n1ound to the bottom of the cosmic ocean on which it floated, thus giving our world stability.24 Thirdly, Irwin argues that this stake is mythologically synonyrnous with the Vedic world axis.2:) He refers to a Vedic cosmogonic n1yth in which lndra, with his vajra, slays the obstructing dragon Vrtra, so as to release the waters of fertility and life locked up in the primaeval mound, floating on the cosmic ocean. At the same time, lndra props up the atn1osphere and heavens with the world axis or tree (which seen1s equivalent to his vajra), and pegs the mound to the ocean bottom, as above. The world axis and Indra's stake can there fore be seen as running into each other, rnerging into one.21 | + | tree, as demonstrated by the way it is addressed in Brahn1anic texts, and the fact that the [[tree]] sections of the yupa (square, octagonal and round) are regarded as representing, respective ly, the [[earth]], the {{Wiki|atmosphere}}, and the heavens.2:-\ Secondly, Irwin notes that "Indra's stake" is the designation, in the [[Vedas]], f(n the stake with which [[Indra]] pegged the primaeval n1ound to the bottom of the [[cosmic]] ocean on which it floated, thus giving our [[world]] stability.24 Thirdly, Irwin argues that this stake is mythologically synonyrnous with the {{Wiki|Vedic}} [[world]] axis.2:) He refers to a {{Wiki|Vedic}} cosmogonic n1yth in which lndra, with his [[vajra]], slays the obstructing [[dragon]] Vrtra, so as to release the waters of {{Wiki|fertility}} and [[life]] locked up in the primaeval mound, floating on the [[cosmic]] ocean. At the same [[time]], lndra props up the atn1osphere and [[heavens]] with the [[world]] axis or [[tree]] (which seen1s equivalent to his [[vajra]]), and pegs the mound to the ocean bottom, as above. The [[world]] axis and Indra's stake can there fore be seen as running into each other, rnerging into one.21 |

| − | Fourthly, Irwin cites certain archaeological evidence which might suggest that Buddhist stupa builders actually conceived of the stOpa axis as symbolising the world axis or world tree of the above Vedic myth.:n Sorne of this evidence is as follows: | + | Fourthly, Irwin cites certain {{Wiki|archaeological}} {{Wiki|evidence}} which might suggest that [[Buddhist]] [[stupa]] builders actually conceived of the stOpa axis as symbolising the [[world]] axis or [[world]] [[tree]] of the above {{Wiki|Vedic}} myth.:n Sorne of this {{Wiki|evidence}} is as follows: |

| − | i) a reliquary from the Great Stupa at Anuradhapura has a y11pa obtruding frorn its top, sprouting leaves as if it were a tree (as shown in figure II). | + | i) a reliquary from the Great [[Stupa]] at [[Anuradhapura]] has a y11pa obtruding frorn its top, sprouting leaves as if it were a [[tree]] (as shown in figure II). |

| − | ii) the description of the relic chamber of the above stupa at Mahiivarrzsa XXX 6:fl. refers to a huge golden Bodhi | + | ii) the description of the [[relic]] chamber of the above [[stupa]] at Mahiivarrzsa XXX 6:fl. refers to a huge golden [[Bodhi tree]] [[standing]] at the centre of the stOpa, as if the [[tree]] were the stfJ pa axis. ' |

| − | iii) the circuman1bulatory paths of son1e early stupas were paved with azure-blue glass tiles, or glazed tiles decorated with water-symbols, suggesting, perhaps, that the stftpa don1e symbolically rests on the cosmic ocean, as did the pri rnaeval mound of Vedic myth.:.!9 | + | iii) the circuman1bulatory [[paths]] of son1e early [[stupas]] were paved with azure-blue glass tiles, or glazed tiles decorated with water-symbols, suggesting, perhaps, that the stftpa don1e [[symbolically]] rests on the [[cosmic]] ocean, as did the pri rnaeval mound of {{Wiki|Vedic}} myth.:.!9 |

| − | lrwin, therefore, sees the stiipa as an image ld' the creation of the universe (the archetype of regeneration), with the stOpa axis founded on the waters and rising through the earth, auno sphere and heavens so as to unite thern and fonn a com•nuni cating link between then1.:w | + | lrwin, therefore, sees the stiipa as an image ld' the creation of the [[universe]] (the archetype of regeneration), with the stOpa axis founded on the waters and rising through the [[earth]], auno [[sphere]] and [[heavens]] so as to unite thern and fonn a com•nuni cating link between then1.:w |

| − | I do not want to rule out Irwin's interpretation (though it seems unlikely), but I feel that there are more "Buddhist" ones easier to hand: after all, the Bodhi | + | I do not want to rule out Irwin's interpretation (though it seems unlikely), but I [[feel]] that there are more "[[Buddhist]]" ones easier to hand: after all, the [[Bodhi tree]] and water-born [[lotus]] are well established [[Buddhist symbols]]. Moreover, Irwin himself [[thinks]] that while the above {{Wiki|Vedic}} [[myth]] affected stiipa construc tion and the meaning of the axis, the {{Wiki|Vedic}} significance came to be mostly forgotten as the old meaning was adapted for the new and increasingly dominant [[doctrinal]] scheme. |

[[File:Lotus Stupa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Lotus Stupa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Inasmuch as the stiipa axis seems to have originated as Vedic sacrificial post, it can surely have taken on a symbolic meaning from this association. To see what this was, we have, firstly, to examine what the Buddhist equivalent of "sacrifice" was. In the Kiltadanta Sutta (0.1.144 fT.) it is said that the Bud dha was once asked by a Brahmin about the best form of "sacri fice." Instead of describing some bloody Brahmanical sacrifice, he answers by talking about giving alms-food and support to monks, Brahmins and the poor, about living a virtuous life, being self-controlled, practicing samatha and vipassanii medita tions, and attaining N ibbana. He describes each such stage of the Buddhist path as a kind of "sacrifice," with the attainment of its goal being the highest and best kind. Again, at D.III.76 it is said that a yupa is the place where a future Cakkavatti emperor will distribute goods to all, renounce his royal life to become a monk under Metteyya Buddha, and go on to become an Ara hant. Therefore, what was once a sacrificial post could natural ly come, in the new religion of Buddhism, to symbolise the Buddhist path and goal-the Dhamma-and all the "sacrifices" involved in these. Indeed, at Miln. 21-22, it is said of the rnonk N agasena that he is engaged in | + | Inasmuch as the stiipa axis seems to have originated as {{Wiki|Vedic}} sacrificial post, it can surely have taken on a [[symbolic]] meaning from this association. To see what this was, we have, firstly, to examine what the [[Buddhist]] equivalent of "sacrifice" was. In the Kiltadanta [[Sutta]] (0.1.144 fT.) it is said that the Bud dha was once asked by a [[Brahmin]] about the best [[form]] of "sacri fice." Instead of describing some bloody {{Wiki|Brahmanical}} sacrifice, he answers by talking about giving alms-food and support to [[monks]], [[Brahmins]] and the poor, about living a [[virtuous]] [[life]], [[being]] self-controlled, practicing [[samatha]] and vipassanii medita tions, and attaining N ibbana. He describes each such stage of the [[Buddhist path]] as a kind of "sacrifice," with the [[attainment]] of its goal [[being]] the [[highest]] and best kind. Again, at D.III.76 it is said that a yupa is the place where a future [[Cakkavatti]] {{Wiki|emperor}} will distribute goods to all, renounce his {{Wiki|royal}} [[life]] to become a [[monk]] under [[Metteyya]] [[Buddha]], and go on to become an Ara hant. Therefore, what was once a sacrificial post could natural ly come, in the new [[religion]] of [[Buddhism]], to symbolise the [[Buddhist path]] and goal-the Dhamma-and all the "sacrifices" involved in these. Indeed, at Miln. 21-22, it is said of the rnonk N agasena that he is engaged in |

| − | pointing out the way of Dharnma, carrying the torch of Dhamma, bearing alr ft the yilfJa r {Dhamma, offering the gift of Dhan1ma ... sounding the drum of Dhamma, roanng the lion's | + | pointing out the way of Dharnma, carrying the torch of [[Dhamma]], bearing alr ft the yilfJa r {[[Dhamma]], [[offering]] the gift of Dhan1ma ... sounding the drum of [[Dhamma]], roanng the [[lion's roar]], thundering out Indra's {{Wiki|thunder}} and thor oughly satisfying the whole [[world]] by thundering out [[sweet]] utterances and wrapping then1 round with the {{Wiki|lightning}} flashes of superb [[knowledge]], filling then1 with the waters of [[compassion]] and the great cloud of the Deathlessness of Dhanuna ... |

[[File:Osel-stupa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Osel-stupa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | This passage certainly shows that Buddhisn1 could draw on Vedic symbolism, but also shows that such symbolism is fully Buddhicized when it is used. "Yilpa" is used as a metaphor for Dhamma: the Buddhist teaching, path and goal, and Indra's releasing of the cosmic waters is a metaphor for a great Dhamma-teacher's com passionate bestowal of that which brings Deathlessness. | + | This passage certainly shows that Buddhisn1 could draw on {{Wiki|Vedic}} [[symbolism]], but also shows that such [[symbolism]] is fully Buddhicized when it is used. "Yilpa" is used as a {{Wiki|metaphor}} for [[Dhamma]]: the [[Buddhist teaching]], [[path]] and goal, and Indra's releasing of the [[cosmic]] waters is a {{Wiki|metaphor}} for a great Dhamma-teacher's com [[passionate]] bestowal of that which brings Deathlessness. |

| − | When we look at the other term for the stiipa axis, "Indra's stake," we also see that this came to have a dear Buddhist meaning. Firstly, we see that from the Vedic myth about In dra's stabilising stake, Jndra-kila came to be a term for the huge pillars standing firmly in the ground at the entrance to ancient Indian and Sinhalese cities, being used to secure the heavy gates when they stood open. It also became a term for the gate posts of houses. Indeed, Jndra-kzla became a term for anything which was stable and firmly rooted and which secured the safe ty of something. While it might be thought that the stiipa axis was called an lndra-kila because it structurally stabilised the stiipa, this does not seem to have been the case, architectural ly.:iJ It is more likely that the axis was an "Indra's stake" in a purely symbolic sense, symbolising the Dhamma, the stable cen tre of a Buddhist's life, which secures his safety in life's troubles and also acts as a "gateway" to a better life and, ultimately, to Deathlessness. The use of "lndra's stake" in metaphors in the suttas indicates that, in particular, the term symbolises that as pect of the Dhamn1a which is the unshakeable state | + | When we look at the other term for the stiipa axis, "Indra's stake," we also see that this came to have a dear [[Buddhist]] meaning. Firstly, we see that from the {{Wiki|Vedic}} [[myth]] about In dra's stabilising stake, Jndra-kila came to be a term for the huge pillars [[standing]] firmly in the [[ground]] at the entrance to ancient [[Indian]] and {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} cities, [[being]] used to secure the heavy gates when they stood open. It also became a term for the gate posts of houses. Indeed, Jndra-kzla became a term for anything which was stable and firmly [[rooted]] and which secured the safe ty of something. While it might be [[thought]] that the stiipa axis was called an lndra-kila because it structurally stabilised the stiipa, this does not seem to have been the case, architectural ly.:iJ It is more likely that the axis was an "Indra's stake" in a purely [[symbolic]] [[sense]], symbolising the [[Dhamma]], the stable cen tre of a Buddhist's [[life]], which secures his safety in life's troubles and also acts as a "gateway" to a better [[life]] and, ultimately, to Deathlessness. The use of "lndra's stake" in metaphors in the [[suttas]] indicates that, in particular, the term symbolises that as pect of the Dhamn1a which is the unshakeable [[state of mind]] of [[Arahants]] and other [[ariyan]] persons. At S.V.444, one who under stands the four [[ariyan]] [[truths]] and has sure and well-founded [[knowledge]] is like an unshakeable lnda-khila, while at Sn.v.229, we read: |

| − | "As an Jnda-khila resting in the earth would be unshakeable by the four winds, of such a kind I say is the good man, who having understood the ariyan truths, sees them (clear ly). This splendid jewel is the Sangha; by this truth may there be well-being." | + | "As an Jnda-khila resting in the [[earth]] would be unshakeable by the four winds, of such a kind I say is the good man, who having understood the [[ariyan]] [[truths]], sees them (clear ly). This splendid [[jewel]] is the [[Sangha]]; by this [[truth]] may there be well-being." |

| − | Dhp.v.95 uses the metaphor specifically of an Arahant: Like the earth, he does not resent; a balanced and well disciplined person is like an Jrula-khila.rfhis is probably also the case at Thag.v.663: | + | Dhp.v.95 uses the {{Wiki|metaphor}} specifically of an [[Arahant]]: Like the [[earth]], he does not resent; a balanced and well [[disciplined]] [[person]] is like an Jrula-khila.rfhis is probably also the case at Thag.v.663: |

[[File:P1174474.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:P1174474.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | But those who in the midst of pain and happiness have overcome the seamstress (craving), stand like an Jnda-khfla; they are neither elated nor cast down. | + | But those who in the midst of [[pain]] and [[happiness]] have overcome the seamstress ([[craving]]), stand like an Jnda-khfla; they are neither [[elated]] nor cast down. |

| − | Referring to the stiipa axis as "lndra's stake," then, would seem to imply that the axis was seen as symbolising the unshakeable state of an ariyan person's Dhamma-filled mind.:i:Z Such symbol ism harmonises with that of the axis as a yupa, and also with that of the don1e as a kumhha, representing the personality of sorne one full of Dhamma. | + | Referring to the stiipa axis as "lndra's stake," then, would seem to imply that the axis was seen as symbolising the unshakeable state of an [[ariyan]] person's Dhamma-filled mind.:i:Z Such symbol ism harmonises with that of the axis as a yupa, and also with that of the don1e as a kumhha, representing the [[personality]] of sorne one full of Dhamma. |

| − | A final aspect of the syrnbolism of the stupa axis is that it was seen to represent Mount Meru, the huge axial world moun tain of Hindu and Buddhist rnythology, with the circular plan of the stflpa don1c representing the circle of the earth. •rhat the stupa was seen in this way, even in Theravada lands, can be seen from several pieces of evidence. Firstly, the huge Bodhi tree which MahiivaT{l,.'ia XXX v.6:1 fl. describes as being in the relic charnber of the Great Stupa at Anuradhapura, is said to have a canopy over it on which are depicted the sun, moon and stars-which are said to revolve round Meru. Around the trees are said to be placed statues of the gods, the Four | + | A final aspect of the syrnbolism of the [[stupa]] axis is that it was seen to represent [[Mount Meru]], the huge axial [[world]] moun tain of [[Hindu]] and [[Buddhist]] rnythology, with the circular plan of the stflpa don1c representing the circle of the [[earth]]. •rhat the [[stupa]] was seen in this way, even in [[Theravada]] lands, can be seen from several pieces of {{Wiki|evidence}}. Firstly, the huge [[Bodhi tree]] which MahiivaT{l,.'ia XXX v.6:1 fl. describes as [[being]] in the [[relic]] charnber of the Great [[Stupa]] at [[Anuradhapura]], is said to have a canopy over it on which are depicted the {{Wiki|sun}}, [[moon]] and stars-which are said to revolve round [[Meru]]. Around the [[trees]] are said to be placed [[statues]] of the [[gods]], the [[Four Great Kings]] who are said to guard the slopes of [[Meru]]; while the [[relic]] charn ber walls are said to have painted on thern zig-zag shaped walls-such walls, at least in the •ribetan [[tradition]], are used to portray the rings of mountains on the disc of the [[earth]]. Second ly, the harmikrl of ancient {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} [[stupas]] sometimes has the {{Wiki|sun}} on the {{Wiki|east}} face and the [[moon]] on the {{Wiki|west}} face. •rhirdly, in late {{Wiki|Sinhalese}} texts, the tern1 for the drun1 at the base of the stiipa spire (see figure 4) is devaW ko(uva, enclosure of the de ities. This corresponds to the [[idea]] that the lower [[gods]] dwell on [[Meru]], with lndra's palace at its summit.:\:\ |

| − | I would see the significance of the Meru symbolism as be ing that the stflpa axis and dome represent the world of gods and men; the implication of this will be brought out below. | + | I would see the significance of the [[Meru]] [[symbolism]] as be ing that the stflpa axis and dome represent the [[world]] of [[gods]] and men; the implication of this will be brought out below. |

[[File:P7181674.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:P7181674.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | V. The Symbolism | + | V. The [[Symbolism]] |

| − | (1• the Stupa as a Whole So far, I have assigned various syn1bolic meanings to the components of the stfrpa. The dorne, container of the precious relics, can be seen to represent a pot full of Dharnma, a Dhan1n1a-wheel, a lotus | + | (1• the [[Stupa]] as a Whole So far, I have assigned various syn1bolic meanings to the components of the stfrpa. The dorne, container of the [[precious]] [[relics]], can be seen to represent a pot full of Dharnma, a Dhan1n1a-wheel, a [[lotus flower]], or the circle of the [[earth]]. 'rhe [[stupa]] axis, as a yupa, symbolises the Dhan1ma ([[teaching]], [[path]] and realizations) and all its "sacrifices," and, as lrula-khila, synl bolises the great stability of the Dhanuna and the unshakeable nature of the [[mind]] full of [[Dhamma]]; it also represents [[Mount Meru]], home of the [[gods]]. On top of the [[stupa]] don1e is a cool "top enclosure" and a _va,yi cotnplete with honourific parasol discs, equivalent to a [[Bodhi tree]], [[symbol]] of a [[Buddha's]] enlight enment and his [[enlightened]] n1ind. |

| − | While a stiipa is worthy of devotion due to the relics it contains, it also serves to inspire because the spnbols of its separate cornponents unite together to n1ake an overall spiritu al staten1ent. The whole symbolises the enlightened n1ind of a Buddha (represented by the _-ya,y(i and parasol-discs as Bodhi tree syrnbols) standing out above the world of gods and humans (represented by the axis and dome). The symbolism shows that the enlightened n1ind arises fnnn within the world by a process of spiritual growth (represented by the don1e as a lotus syn1bol, or as a vase of plenty) on a finn basis of the practice of Dhatnma (represented by the don1e as a Dharnrna-wheel). | + | While a stiipa is [[worthy]] of devotion due to the [[relics]] it contains, it also serves to inspire because the spnbols of its separate cornponents unite together to n1ake an overall spiritu al staten1ent. The whole symbolises the [[enlightened]] n1ind of a [[Buddha]] (represented by the _-ya,y(i and parasol-discs as [[Bodhi tree]] syrnbols) [[standing]] out above the [[world]] of [[gods]] and [[humans]] (represented by the axis and dome). The [[symbolism]] shows that the [[enlightened]] n1ind arises fnnn within the [[world]] by a process of [[spiritual]] growth (represented by the don1e as a [[lotus]] syn1bol, or as a vase of plenty) on a finn basis of the practice of Dhatnma (represented by the don1e as a Dharnrna-wheel). |

| − | This Dharnrna (now represented by the axis) is also the path which leads up out of the world of humans and gods to enlightenment (repre sented by the ya (i and parasol-discs, resting on top of the axis as its uppermost portion). A personality (the dorne as a kumbha) full of such Dhamrna is worthy of reverence and has an unshakeable n1ind (represented by the axis as hula-khlla, with the .Wt- '(i as its extension). In brief, we could say that the stiipa symbolises the Dhamrna and the transfonnations it brings in one who practices it, culruinating in enlightenrnent. It is not surprising, then, that at an early date, the various layers of the stiipa's structure were explicitly seen as symbolising specific aspects of the Dhamma (teaching, path and culmination) and of a Buddha's nature. Gustav Roth has translated, from their Tibetan versions, two ancient Sanskrit texts which see the stllpa as symbolising the Dharmakc1ya in the sense of the :7 "requisites of cnlightenn1cnt" (bodhipak i.va-dlwrmas) and certain other spiritual qualities.:H These texts arc the first century A.D. Cai lya-viblut{{a-viuayabluiva Siilra, frat-{tnents of an unknown Vin aya, and the second century A. D. SLiijm-fakyaua-lulrilal-1'ivf'tww of the Lokouaravadin Vinaya. | + | This Dharnrna (now represented by the axis) is also the [[path]] which leads up out of the [[world]] of [[humans]] and [[gods]] to [[enlightenment]] (repre sented by the ya (i and parasol-discs, resting on top of the axis as its uppermost portion). A [[personality]] (the dorne as a [[kumbha]]) full of such Dhamrna is [[worthy]] of reverence and has an unshakeable n1ind (represented by the axis as hula-khlla, with the .Wt- '(i as its extension). In brief, we could say that the stiipa symbolises the Dhamrna and the transfonnations it brings in one who practices it, culruinating in enlightenrnent. It is not surprising, then, that at an early date, the various layers of the stiipa's structure were explicitly seen as symbolising specific aspects of the [[Dhamma]] ([[teaching]], [[path]] and culmination) and of a [[Buddha's]] nature. Gustav Roth has translated, from their Tibetan versions, two ancient [[Sanskrit]] texts which see the stllpa as symbolising the Dharmakc1ya in the [[sense]] of the :7 "requisites of cnlightenn1cnt" (bodhipak i.va-dlwrmas) and certain other [[spiritual]] qualities.:H These texts arc the first century A.D. Cai lya-viblut{{a-viuayabluiva Siilra, frat-{tnents of an unknown Vin aya, and the second century A. D. SLiijm-fakyaua-lulrilal-1'ivf'tww of the Lokouaravadin Vinaya. |

[[File:Sanchi-stupa01.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Sanchi-stupa01.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

A scheme of symbolic corrcspondences identical with that outlined in the first of these texts is shown in figure 12. Each layer of the stllpa's structure repre sents a group of spiritual qualities cultivated on the path, while the spire represents the powers of a Tathagata.: ;, | A scheme of symbolic corrcspondences identical with that outlined in the first of these texts is shown in figure 12. Each layer of the stllpa's structure repre sents a group of spiritual qualities cultivated on the path, while the spire represents the powers of a Tathagata.: ;, | ||

Revision as of 09:19, 7 September 2013

by Peter Harvey

I. Introduction

In this paper, I wish to focus on the symbolism of the Buddhist stiipa. In its simplest sense, this is a "(relic) mound" and a symbol of the Buddha's parinibbiina. I wish to show, how ever, that its form also comprises a system of overlapping sym bols which make the stupa as a whole into a symbol of the Dhamma and of the enlightened state of a Buddha.

Some authors, such as John Irwin,1 Ananda Coomaras wamy,and, to some extent, Lama Anagarika Govinda,:have seen a largely pre-Buddhist, Vedic rneaning in the stupa's sym bolism. I wish to bring out its Buddhist meaning, drawing on certain evidence cited by Irwin in support of his interpretation, and on the work of such scholars as Gustav Roth.4

II. The Origins of the Stupa

From pre-Buddhist times, in India and elsewhere, the re mains of kings and heroes were interred in burial mounds (tu muli), out of both respect and fear of the dead. Those in an cient India were low, circular mounds of earth, kept in place by a ring of boulders; these boulders also served to mark off a mound as a sacred area.

According to the account in the Mahiiparinibbiina Sutta (D.Il.l41-3), when the Buddha was asked what was to be done

- First given at the Eighth Symposium on Indian Religions (British Association for the History of Religion), Oxford, April

1982 with his remains after death, he seems to have brought to mind this ancient tradition. He explained that his body should be treated like that of a Cakkavatti emperor: after wrapping it in many layers of cloth and placing it within two iron vessels, it should be cremated; the relics should then be placed in a stupa "where four roads meet" (ciitummahiipathe). The relics of a "dis ciple" (siivaka) of a Tathagata should be treated likewise. At the stupa of either, a person's citta could be gladdened and calmed at the thought of its significance.

After the Buddha's cremation, his relics (sariras) are said to have been divided into eight portions, and each was placed in a stupa. The pot (kumbha) in which the relics were collected and the ashes of the cremation fire were dealt with in the same way (D.I 1.166).

()ne of the things which Asoka (273-232 B.C.) did in his efforts to spread Buddhism, was to open up these original ten stupas and distribute their relics in thousands of new stupas throughout India. By doing this, the stiipa was greatly popular ised. Though the development of the Buddha-image, probably in the second century A.D., provided another focus for devo tion to the Buddha, stiipas remain popular to this day, especial ly in Theravadin countries. rfhey have gone through a long development in form and symbolism, but I wish to concentrate on their early significance.

Ill. Relics

Before dealing with the stupa itself, it is necessary to say something about the relics contained in it. The contents of a stiipa may be the reputed physical relics (sariras or dhiitus) of Gotama Buddha, of a previous Buddha, of an Arahant or other saint, or copies of these relics; they may also be o jects used by such holy beings, images symbolising them, or texts seen as the "relics" of the "Dhamma-body" of Gotama Buddha.

Physical relics are seen as the most powerful kind of contents. Firstly, they act as reminders of a Buddha or saint: of their spiritual qualities, their teachings, and the fact that they have actually lived on this earth. 'fhis, in turn, shows that it is possible for a human being to become a Buddha or saint. While even copies of relics can act as reminders, they cannot fulfill the second function of relics proper. This is because these are thought to contain something of the spiritual force and purity of the person they once formed part of. As they were part of the body of a person whose mind was freed of spiritual faults and possessed of a great energy-for-good, it is believed that they were somehow affected by this. Relics are therefore seen as radiating a kind of beneficial power. This is probably why ch.

28 of the Buddhavarpsa says: The ancients say that the dispersal of the relics of Gotama, the great seer, was out of compassion for living beings.

Miraculous powers are also attributed to relics, as seen in a story of the second century B.C. related in the Mahiiva1{1Sa XXXI v.97-IOO. When king DunhagamaQi was enshrining some relics of Gotama in the Great Stiipa at Anuradhapura, they rose into the air in their casket, and then emerged to form the shape of the Buddha. In a similar vein, the Vibhanga AUha katha p. 433 says that at the end of the 5000 year period of the siisana, all the relics in Sri Lanka will assemble, travel through the air to the foot of the Bodhi tree in India, emit rays of light, and then disappear in a flash of light. l his is referred to as the parinibbiina of the dhiitus. Relics, then, act both as reminders of Gotama, or some other holy being, and as actual tangible links with them and their spiritual powers. The Mahava1{1Sa XXX v.1 00 says, indeed, that there is equal merit in devotion to the Buddha's relics as there was in devotion to him when he was alive.

IV. The Symbolism of the Stiipa's Components

The best preserved of the early Indian stupas is the Great Stiipa at Saflci, central India. First built by Asoka, it was later enlarged and embellished, up to the first century A.D. The diagramatic representation of it in figure I gives a clear indica tion of the various parts of an early stu pa.

The four torarJa.5, or gateways, of this stupa were built between the first centuries B.C. and A.D., to replace previous wooden ones. Their presence puts the stflpa, symbolically, at the place where four roads meet, as is specified in the Mahapar inibbflna Sutta. This is probably to indicate the openness and universality of the Buddhist teaching, which invites all to come and try its path, and also to radiate loving-kindness to beings in all four directions.

In a later development of the stiipa, in North India, the orientation to the four directions was often expressed by n1eans of a square, terraced base, sornetimes with staircases on each side in place of the early gateways. At Sand, these gateways arc covered with carved reliefs of the Bodhisatta career of Gotarna and also, using aniconic syrnbols, of his final life as a Buddha. Symbols also represent previous Buddhas. In this way, the gates convey Buddhist teachings and the life of the Buddhas to those who enter the precincts of the stflpa.