Difference between revisions of "Sentient beings"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

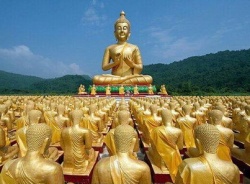

| − | + | [[File:Buddhas.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

| − | Sentient beings is a technical term in Buddhist discourse. Broadly speaking, it denotes beings with consciousness or sentience or, in some contexts, life itself. | + | Sentient beings is a technical term in Buddhist discourse. Broadly speaking, it denotes beings with consciousness or sentience or, in some contexts, life itself. Specifically, it denotes the presence of the five aggregates, or skandhas. While distinctions in usage and potential subdivisions or classes of sentient beings vary from one school, teacher, or thinker to another—and there is debate within some Buddhist schools as to what exactly constitutes sentience and how it is to be recognized—it principally refers to beings in contrast with buddhahood. That is, sentient beings are characteristically not enlightened, and are thus confined to the death, rebirth, and suffering characteristic of Saṃsāra. However, Mahayana Buddhism simultaneously teaches (in the Tathagatagarbha doctrine particularly) that sentient beings also contain Buddha-nature—the intrinsic potential to transcend the conditions of samsara and attain enlightenment, thereby becoming a Buddha. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :"Those who greatly enlighten illusion are Buddhas; those who are greatly deluded about enlightenment are sentient beings."::—Dōgen | |

| − | + | In Mahayana Buddhism, it is to sentient beings that the Bodhisattva vow of compassion is pledged. Furthermore, and particularly in Tibetan Buddhism and Japanese Buddhism, all beings (including plant life and even inanimate objects or entities considered "spiritual" or "metaphysical" by conventional Western thought) are or may be considered sentient beings. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The Chinese Scholar T'ien-T'ai (538–597) taught that plants, and other insentient objects could attain Buddhahood. This is because of the principle of Ichinen Sanzen (Eng. 3,000 Realms in a Single Thought Moment). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | == Definition == | |

| + | |||

| + | Getz (2004: p. 760) provides a generalist Western Buddhist encyclopedic definition: | ||

| + | |||

| + | : Sentient beings is a term used to designate the totality of living, conscious beings that constitute the object and audience of Buddhist teaching. Translating various Sanskrit terms (jantu, bahu jana, jagat, sattva), sentient beings conventionally refers to the mass of living things subject to illusion, suffering, and rebirth (Saṃsāra). Less frequently, sentient beings as a class broadly encompasses all beings possessing consciousness, including Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. | ||

| − | + | == Classification == | |

| − | + | Early scriptures in the Pali Canon and the conventions of the Tibetan Bhavachakra classify sentient beings into five categories—divinities, humans, animals, tormented spirits, and denizens of hell—although sometimes the classification adds another category of demonic beings between divinities and humans. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | {{R}} | |

| − | [[ | + | [[Wikipedia:Sentient beings (Buddhism)]] |

[[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | ||

| − | [[Category:Buddhist | + | [[Category:Buddhist philosophical concepts]] |

Revision as of 12:27, 24 December 2012

Sentient beings is a technical term in Buddhist discourse. Broadly speaking, it denotes beings with consciousness or sentience or, in some contexts, life itself. Specifically, it denotes the presence of the five aggregates, or skandhas. While distinctions in usage and potential subdivisions or classes of sentient beings vary from one school, teacher, or thinker to another—and there is debate within some Buddhist schools as to what exactly constitutes sentience and how it is to be recognized—it principally refers to beings in contrast with buddhahood. That is, sentient beings are characteristically not enlightened, and are thus confined to the death, rebirth, and suffering characteristic of Saṃsāra. However, Mahayana Buddhism simultaneously teaches (in the Tathagatagarbha doctrine particularly) that sentient beings also contain Buddha-nature—the intrinsic potential to transcend the conditions of samsara and attain enlightenment, thereby becoming a Buddha.

- "Those who greatly enlighten illusion are Buddhas; those who are greatly deluded about enlightenment are sentient beings."::—Dōgen

In Mahayana Buddhism, it is to sentient beings that the Bodhisattva vow of compassion is pledged. Furthermore, and particularly in Tibetan Buddhism and Japanese Buddhism, all beings (including plant life and even inanimate objects or entities considered "spiritual" or "metaphysical" by conventional Western thought) are or may be considered sentient beings.

The Chinese Scholar T'ien-T'ai (538–597) taught that plants, and other insentient objects could attain Buddhahood. This is because of the principle of Ichinen Sanzen (Eng. 3,000 Realms in a Single Thought Moment).

Definition

Getz (2004: p. 760) provides a generalist Western Buddhist encyclopedic definition:

- Sentient beings is a term used to designate the totality of living, conscious beings that constitute the object and audience of Buddhist teaching. Translating various Sanskrit terms (jantu, bahu jana, jagat, sattva), sentient beings conventionally refers to the mass of living things subject to illusion, suffering, and rebirth (Saṃsāra). Less frequently, sentient beings as a class broadly encompasses all beings possessing consciousness, including Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

Classification

Early scriptures in the Pali Canon and the conventions of the Tibetan Bhavachakra classify sentient beings into five categories—divinities, humans, animals, tormented spirits, and denizens of hell—although sometimes the classification adds another category of demonic beings between divinities and humans.