Difference between revisions of "Manual Of Prajna Paramita"

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

BUDDHIST REFUGE | BUDDHIST REFUGE | ||

| − | Level 1of The Perfection of [[Wisdom]] (Prajna Paramita) | + | Level 1of The [[Perfection]] of [[Wisdom]] ([[Prajna]] Paramita) |

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Reading One: The Three Kinds of [[Refuge]] | Reading One: The Three Kinds of [[Refuge]] | ||

| − | From the presentation on The Three [[Refuges]] found in the Analysis of the Perfection of [[Wisdom]], by [[Kedrup Tenpa Dargye]] (1493-1568): | + | From the presentation on The Three [[Refuges]] found in the Analysis of the [[Perfection]] of [[Wisdom]], by [[Kedrup Tenpa Dargye]] (1493-1568): |

| − | Here we will discuss the line of the root text which says, “The [[Three Jewels]], the [[Buddha]] and the rest.” Let us first consider the section of the middle-length [[sutra]] on the Mother which includes the lines: | + | Here we will discuss the line of the [[root]] text which says, “The [[Three Jewels]], the [[Buddha]] and the rest.” Let us first consider the section of the middle-length [[sutra]] on the Mother which includes the lines: |

| − | Do not think that this very [[Knowledge]] of All Things is something which applies to what you can see, and do not think it is separate from what you can see. Just so, never view what you can see itself as being real. | + | Do not think that this very [[Knowledge]] of All Things is something which applies to what you can see, and do not think it is separate from what you can see. Just so, never [[view]] what you can see itself as [[being]] real. |

These are the “Instruction on the [[Three Jewels]],” for they are words from the middle-length [[sutra]] on the Mother which give us the following advice: | These are the “Instruction on the [[Three Jewels]],” for they are words from the middle-length [[sutra]] on the Mother which give us the following advice: | ||

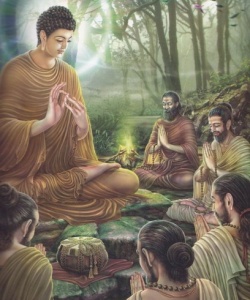

[[File:000x297x1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:000x297x1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | These [[Three Jewels]] are no place of [[refuge]] for persons who seek an ultimate [[liberation]]. They are a place of [[refuge]] for persons who seek a [[liberation]] only in words. | + | These [[Three Jewels]] are no place of [[refuge]] for persons who seek an [[ultimate]] [[liberation]]. They are a place of [[refuge]] for persons who seek a [[liberation]] only in words. |

Our analysis of this section will proceed in three parts: a refutation of our opponent’s position, a presentation of our own position, and a rebuttal of their objections. | Our analysis of this section will proceed in three parts: a refutation of our opponent’s position, a presentation of our own position, and a rebuttal of their objections. | ||

| − | Here is the second section, in which we present our own position. There is a specific reason why the [[Three Jewels]] are established as being the [[refuges]] for practitioners of the three classes. From the point of view of cause [[refuge]], practitioners of all three classes take refuge in all three of the Jewels. But from the point of view of result [[refuge]], those of the Listener class aspire chiefly to attain the state of a foe destroyer. | + | Here is the second section, in which we present our own position. There is a specific [[reason]] why the [[Three Jewels]] are established as [[being]] the [[refuges]] for practitioners of the three classes. From the point of [[view]] of [[cause]] [[refuge]], practitioners of all three classes take [[refuge]] in all three of the Jewels. But from the point of [[view]] of result [[refuge]], those of the Listener class aspire chiefly to attain the state of a foe destroyer. |

| − | Those of the class of Self-Made [[Buddhas]] aspire chiefly to attain that meditative wisdom where they abide in a [[meditation]] of [[cessation]], a state where all the obstacles of the mental afflictions have been eliminated. | + | Those of the class of Self-Made [[Buddhas]] aspire chiefly to attain that [[meditative]] [[wisdom]] where they abide in a [[meditation]] of [[cessation]], a state where all the obstacles of the [[mental]] [[afflictions]] have been eliminated. |

| − | Those of the Greater Way aspire chiefly to attain the [[Buddha]] Jewel, one who possesses that cause within him which will allow him to turn the wheel of the [[dharma]], in its entirety, for [[disciples]] of all three classes. This then is the reason why the [[Three Jewels]] are established as being [[refuges]] for practitioners of the three classes. | + | Those of the Greater Way aspire chiefly to attain the [[Buddha]] [[Jewel]], one who possesses that [[cause]] within him which will allow him to turn the [[wheel]] of the [[dharma]], in its entirety, for [[disciples]] of all three classes. This then is the [[reason]] why the [[Three Jewels]] are established as [[being]] [[refuges]] for practitioners of the three classes. |

| − | The definition of the [[Buddha]] Jewel is “That ultimate place of [[refuge]], the one which has completely satisfied both the needs.” There are two kinds of [[Buddha]] Jewel: the apparent [[Buddha]] Jewel, and the ultimate [[Buddha]] Jewel. | + | The definition of the [[Buddha]] [[Jewel]] is “That [[ultimate]] place of [[refuge]], the one which has completely satisfied both the needs.” There are two kinds of [[Buddha]] [[Jewel]]: the apparent [[Buddha]] [[Jewel]], and the [[ultimate]] [[Buddha]] Jewel. |

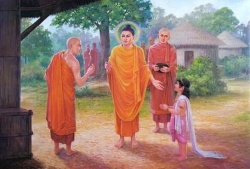

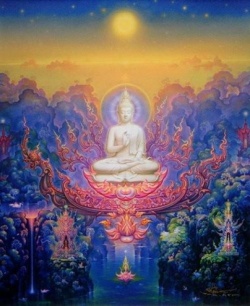

[[File:002asd.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:002asd.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | This [[Buddha]] Jewel posseses eight different fine qualities, beginning with the quality of being uncaused. As the Higher Line states, | + | This [[Buddha]] [[Jewel]] posseses eight different fine qualities, beginning with the quality of [[being]] uncaused. As the Higher Line states, |

This is the One, the [[Buddha]]: | This is the One, the [[Buddha]]: | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

He is uncaused, He is spontaneous, | He is uncaused, He is spontaneous, | ||

| − | He is realized by no other way; | + | He is [[realized]] by no other way; |

| − | He has [[knowledge]], and love, and power; | + | He has [[knowledge]], and [[love]], and power; |

He has satisfied both the needs. | He has satisfied both the needs. | ||

| − | The definition of the [[Dharma]] Jewel is “The [[enlightened]] side of {{Wiki|truth}}, either in the form of a [[cessation]], or in the form of a path, or both.” In name only this Jewel can be divided into two kinds: the ultimate [[Dharma]] Jewel, and the apparent [[Dharma]] Jewel. | + | The definition of the [[Dharma]] [[Jewel]] is “The [[enlightened]] side of {{Wiki|truth}}, either in the [[form]] of a [[cessation]], or in the [[form]] of a [[path]], or both.” In [[name]] only this [[Jewel]] can be divided into two kinds: the [[ultimate]] [[Dharma]] [[Jewel]], and the apparent [[Dharma]] Jewel. |

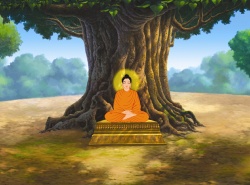

[[File:00x2400.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:00x2400.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The definition of the [[Sangha]] Jewel is “A realized being who possesses any number of the eight fine qualities of [[knowledge]] and [[liberation]].” In name only, this Jewel can be divided into two kinds: the ultimate [[Sangha]] Jewel, and the apparent [[Sangha]] Jewel. | + | The definition of the [[Sangha]] [[Jewel]] is “A [[realized]] [[being]] who possesses any number of the eight fine qualities of [[knowledge]] and [[liberation]].” In [[name]] only, this [[Jewel]] can be divided into two kinds: the [[ultimate]] [[Sangha]] [[Jewel]], and the apparent [[Sangha]] Jewel. |

| − | The definition of an ultimate refuge is “Any refuge where the journey along the path has reached its final goal.” | + | The definition of an [[ultimate]] [[refuge]] is “Any [[refuge]] where the journey along the [[path]] has reached its final goal.” |

| − | The definition of an apparent refuge is “Any refuge where the journey along the path has not reached its final goal.” | + | The definition of an apparent [[refuge]] is “Any [[refuge]] where the journey along the [[path]] has not reached its final goal.” |

| − | The definition of taking refuge is “Any movement of the mind that acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that some object outside of one’s self will be able to render one assistance.” | + | The definition of [[taking refuge]] is “Any movement of the [[mind]] that acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that some [[object]] outside of one’s [[self]] will be able to render one assistance.” |

| − | In name only, taking refuge may be divided into two: taking refuge in words, the expression of refuge; and taking refuge in thoughts, the reliance on refuge. An example of the first would be something like the words you use as you take refuge. | + | In [[name]] only, [[taking refuge]] may be divided into two: [[taking refuge]] in words, the expression of [[refuge]]; and [[taking refuge]] in [[thoughts]], the reliance on [[refuge]]. An example of the first would be something like the words you use as you take refuge. |

| − | The latter is of two types: ordinary taking of refuge, and exceptional taking of refuge. The definition of the first is “Any movement of the mind which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that some ordinary type of refuge will render one assistance.” | + | The latter is of two types: ordinary taking of [[refuge]], and [[exceptional]] taking of [[refuge]]. The definition of the first is “Any movement of the [[mind]] which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that some ordinary type of [[refuge]] will render one assistance.” |

| − | The definition of the latter is “Any movement of the mind which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that any one or number of the Three Jewels will render one assistance.” | + | The definition of the latter is “Any movement of the [[mind]] which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that any one or number of the [[Three Jewels]] will render one assistance.” |

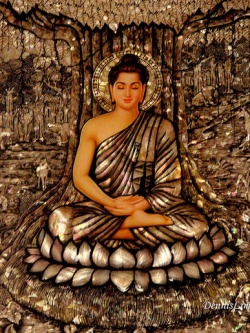

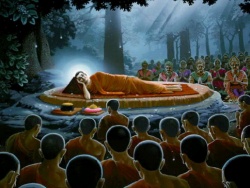

[[File:0147.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:0147.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | There are five different kinds of this extraordinary taking of refuge: the taking of refuge which is shared with practitioners of a lesser scope, the taking of refuge which is shared with practitioners of a medium scope, the taking of refuge which is shared with practitioners of a greater scope, cause refuge, and result refuge. | + | There are five different kinds of this [[extraordinary]] taking of [[refuge]]: the taking of [[refuge]] which is shared with practitioners of a lesser scope, the taking of [[refuge]] which is shared with practitioners of a medium scope, the taking of [[refuge]] which is shared with practitioners of a greater scope, [[cause]] [[refuge]], and result refuge. |

| − | Here are their respective definitions. The first is defined as: “First, you feel a personal fear for the sufferings of the births of misery. Second, you believe that the Three Jewels possess the power to protect you from these sufferings. Finally you have a thought which acts of its own accord: it is a hope, or something of the type, that some one or number of the Three Jewels will render you assistance, to protect you from these sufferings. | + | Here are their respective definitions. The first is defined as: “First, you [[feel]] a personal {{Wiki|fear}} for the [[sufferings]] of the [[births]] of [[misery]]. Second, you believe that the [[Three Jewels]] possess the [[power]] to protect you from these [[sufferings]]. Finally you have a [[thought]] which acts of its own accord: it is a {{Wiki|hope}}, or something of the type, that some one or number of the [[Three Jewels]] will render you assistance, to protect you from these sufferings. |

| − | The second is defined as: “First, you feel a personal fear for each and every suffering of the cycle of life. Second, you believe that the Three Jewels possess the power to protect you from these sufferings. Finally you have a movement of the mind which acts of its own accord: it is a hope, or something of the type, that some one or number of the Three Jewels will render you assistance, to protect you from these sufferings. | + | The second is defined as: “First, you [[feel]] a personal {{Wiki|fear}} for each and every [[suffering]] of the cycle of [[life]]. Second, you believe that the [[Three Jewels]] possess the [[power]] to protect you from these [[sufferings]]. Finally you have a movement of the [[mind]] which acts of its own accord: it is a {{Wiki|hope}}, or something of the type, that some one or number of the [[Three Jewels]] will render you assistance, to protect you from these sufferings. |

| − | The third is defined as: “Any movement of the mind which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that any one or number of the Three Jewels will render assistance, to protect every living being from the sufferings of the cycle of life.” | + | The third is defined as: “Any movement of the [[mind]] which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that any one or number of the [[Three Jewels]] will render assistance, to protect every [[living being]] from the [[sufferings]] of the cycle of life.” |

| − | The fourth is defined as: “Any movement of the mind which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that any one or number of the Three Jewels, as already achieved in another person, will render assistance.” The fifth is defined as: “Any movement of the mind which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that any one or number of the Three Jewels, as they are to be achieved within ones self, will render assistance.” | + | The fourth is defined as: “Any movement of the [[mind]] which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that any one or number of the [[Three Jewels]], as already achieved in another [[person]], will render assistance.” The fifth is defined as: “Any movement of the [[mind]] which acts of its own accord, and consists of hoping that any one or number of the [[Three Jewels]], as they are to be achieved within ones [[self]], will render assistance.” |

[[File:01g.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:01g.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | There is a specific purpose for taking refuge in the Three Jewels. A temporal purpose is that they can provide you the highest form of protection. The ultimate purpose is to attain the state of enlightenment. | + | There is a specific purpose for [[taking refuge]] in the [[Three Jewels]]. A temporal purpose is that they can provide you the [[highest]] [[form]] of protection. The [[ultimate]] purpose is to attain the state of enlightenment. |

| − | Taking refuge also serves as the foundation for all the different kinds of vows. When you take refuge, you thereby join the ranks of the “ones inside”: you become a Buddhist. This taking refuge acts as well to slam shut the door to the births of misery. These and others are the purpose for taking refuge in the Three. | + | Taking [[refuge]] also serves as the foundation for all the different kinds of [[vows]]. When you take [[refuge]], you thereby join the ranks of the “ones inside”: you become a [[Buddhist]]. This [[taking refuge]] acts as well to slam shut the door to the [[births]] of [[misery]]. These and others are the purpose for [[taking refuge]] in the Three. |

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

Reading Two: The Wish for Enlightenment | Reading Two: The Wish for Enlightenment | ||

| − | From the presentation on The Wish for Enlightenment found in the Overview of the Perfection of Wisdom, by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): | + | From the presentation on The Wish for [[Enlightenment]] found in the Overview of the [[Perfection of Wisdom]], by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): |

| − | Here we will discuss the lines of the root text which begin with “The wish for enlightenment is, for the benefit of others…” First we will relate this concept to the original texts, and then we will analyze it in detail. | + | Here we will discuss the lines of the [[root]] text which begin with “The wish for [[enlightenment]] is, for the benefit of others…” First we will relate this {{Wiki|concept}} to the original texts, and then we will analyze it in detail. |

Here is the first. We find the following lines in sutra: | Here is the first. We find the following lines in sutra: | ||

[[File:01jpegn.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:01jpegn.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Sharibu, those who wish to gain total enlightenment, a knowledge of every kind of thing, must train themselves in the perfection of wisdom. Those who wish this, and that, must train themselves in the wisdom perfection. | + | Sharibu, those who wish to gain total [[enlightenment]], a [[knowledge]] of every kind of thing, must train themselves in the [[perfection of wisdom]]. Those who wish this, and that, must train themselves in the [[wisdom]] perfection. |

| − | The root text and commentary include other lines that begin with “The wish for enlightenment is” and continue up to “the twenty-two.” The function of these latter sections is to clarify the hidden meaning of the words of the sutra, including as it does the essential nature of the wish for enlightenment. | + | The [[root]] text and commentary include other lines that begin with “The wish for [[enlightenment]] is” and continue up to “the twenty-two.” The [[function]] of these latter sections is to clarify the hidden meaning of the words of the [[sutra]], including as it does the [[essential]] nature of the wish for enlightenment. |

| − | As such, we can understand the definition of the wish for enlightenment as “The wish to achieve total enlightenment for the benefit of others.” | + | As such, we can understand the definition of the wish for [[enlightenment]] as “The wish to achieve total [[enlightenment]] for the benefit of others.” |

| − | Here is the section in which we present our own position. The definition of the greater way’s wish for enlightenment is as follows. | + | Here is the section in which we present our own position. The definition of the greater way’s wish for [[enlightenment]] is as follows. |

| − | First, it is that main mental awareness belonging to the greater way, which is focussed on achieving total enlightenment for the benefit of others, and which is matched with a state of mind that is associated with it: the aspiration to achieve total enlightenment. | + | First, it is that main [[mental]] [[awareness]] belonging to the greater way, which is focussed on achieving total [[enlightenment]] for the benefit of others, and which is matched with a [[state of mind]] that is associated with it: the [[aspiration]] to achieve total enlightenment. |

| − | Secondly, it is a knowledge belonging to the greater way, which acts as a door for entering the greater way (or is something of the type), and which is included into the activity side of the standard division into the two of | + | Secondly, it is a [[knowledge]] belonging to the greater way, which acts as a door for entering the greater way (or is something of the type), and which is included into the [[activity]] side of the standard division into the two of “[[view]]” and “activity.” |

[[File:038f9e01a.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:038f9e01a.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Here next are the divisions of this wish. Nominally, the wish can be divided into the apparent wish for enlightenment and the ultimate wish for enlightenment. In essence, it can be divided into the wish of prayer and the wish of engagement. In terms of level, it can be divided into the four types that begin with “the wish that acts out of belief.” In terms of how the wish is developed, there are three types, starting with the “king’s wish.” | + | Here next are the divisions of this wish. Nominally, the wish can be divided into the apparent wish for [[enlightenment]] and the [[ultimate]] wish for [[enlightenment]]. In [[essence]], it can be divided into the wish of [[prayer]] and the wish of engagement. In terms of level, it can be divided into the four types that begin with “the wish that acts out of [[belief]].” In terms of how the wish is developed, there are three types, starting with the “king’s wish.” |

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

Reading Three: What is Nirvana? | Reading Three: What is Nirvana? | ||

| − | From the presentation on Nirvana found in the Analysis of the Perfection of Wisdom, by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): | + | From the presentation on [[Nirvana]] found in the Analysis of the [[Perfection of Wisdom]], by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): |

| − | Here secondly is the section in which we present our own position. The definition of nirvana is “A cessation which comes from the individual analysis, and which consists of having eliminated the mental-affliction obstacles in their entirety.” | + | Here secondly is the section in which we present our own position. The definition of [[nirvana]] is “A [[cessation]] which comes from the {{Wiki|individual}} analysis, and which consists of having eliminated the mental-affliction obstacles in their entirety.” |

| − | In name only, nirvana can be divided into the following four types: natural nirvana, nirvana with something left over, nirvana with nothing left over, and nirvana which does not stay. | + | In [[name]] only, [[nirvana]] can be divided into the following four types: natural [[nirvana]], [[nirvana]] with something left over, [[nirvana]] with [[nothing]] left over, and [[nirvana]] which does not stay. |

[[File:04351.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:04351.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The following all refer to the same thing: natural nirvana, the natural Mother, the natural perfection of wisdom, the natural Dharma Body, and ultimate truth. The definition of nirvana with something left over is: “A cessation which comes from the individual analysis, and which consists of having eliminated the mental-affliction obstacles in their entirety, but where one still has the suffering heaps that are a result of his past actions and bad thoughts.” A classical example of this would be the nirvana found in the mental stream of a listener who is a foe destroyer, and who has not yet shucked off the heaps he took on. The definition of nirvana with nothing left over is: “A cessation which comes from the individual analysis, and which consists of having eliminated the mental-affliction obstacles in their entirety, and where one is free of the suffering heaps that are a result of his past actions and bad thoughts.” A classical example of this would be the nirvana found in the mental stream of a listener who is a foe destroyer, and who has shucked off the heaps he took on. | + | The following all refer to the same thing: natural [[nirvana]], the natural Mother, the natural [[perfection of wisdom]], the natural [[Dharma Body]], and [[ultimate truth]]. The definition of [[nirvana]] with something left over is: “A [[cessation]] which comes from the {{Wiki|individual}} analysis, and which consists of having eliminated the mental-affliction obstacles in their entirety, but where one still has the [[suffering]] heaps that are a result of his past [[actions]] and bad [[thoughts]].” A classical example of this would be the [[nirvana]] found in the [[mental]] stream of a listener who is a foe destroyer, and who has not yet shucked off the heaps he took on. The definition of [[nirvana]] with [[nothing]] left over is: “A [[cessation]] which comes from the {{Wiki|individual}} analysis, and which consists of having eliminated the mental-affliction obstacles in their entirety, and where one is free of the [[suffering]] heaps that are a result of his past [[actions]] and bad [[thoughts]].” A classical example of this would be the [[nirvana]] found in the [[mental]] stream of a listener who is a foe destroyer, and who has shucked off the heaps he took on. |

| − | The definition of nirvana which does not stay is: “A cessation which comes from the individual analysis, and which consists of having eliminated both kinds of obstacles in their entirety.” A classical example of this would be the truth of cessation in the mental stream of a realized being who is a Buddha. The nirvana we are describing here is not something that one can achieve by using any method at all. Rather, you must achieve it with the training of wisdom, which realizes that nothing has any self nature; this wisdom must be under the influence of the first two trainings, and with it you must habituate yourself to what you were already able to realize. | + | The definition of [[nirvana]] which does not stay is: “A [[cessation]] which comes from the {{Wiki|individual}} analysis, and which consists of having eliminated both kinds of obstacles in their entirety.” A classical example of this would be the [[truth]] of [[cessation]] in the [[mental]] stream of a [[realized]] [[being]] who is a [[Buddha]]. The [[nirvana]] we are describing here is not something that one can achieve by using any method at all. Rather, you must achieve it with the training of [[wisdom]], which realizes that [[nothing]] has any [[self]] nature; this [[wisdom]] must be under the [[influence]] of the first two trainings, and with it you must [[habituate]] yourself to what you were already able to realize. |

| − | This fact is supported by the King of Concentration | + | This fact is supported by the [[King]] of [[Concentration]]h states: |

Suppose you are able to analyze | Suppose you are able to analyze | ||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

This is what then leads you to | This is what then leads you to | ||

| − | Achieve your freedom; nirvana beyond grief. | + | Achieve your freedom; [[nirvana]] beyond grief. |

It is impossible for any other | It is impossible for any other | ||

| − | Cause to bring this peace to you. | + | Cause to bring this [[peace]] to you. |

| − | Reading Four: The Object We Deny | + | Reading Four: The [[Object]] We Deny |

[[File:10d2fd63.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:10d2fd63.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | From the presentation on The Object We Deny found in the Overview of the Perfection of Wisdom, by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): | + | From the presentation on The [[Object]] We Deny found in the Overview of the [[Perfection of Wisdom]], by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): |

| − | Next we will explain what it means when we say that the three of basic knowledge, path knowledge, and the knowledge of all things have no real nature of arising. This explanation has three parts: identifying what it is we deny with reasoning that treats the ultimate; introducing the various reasons used to deny this object; and, once we have established these two, detailing the steps to develop correct view. | + | Next we will explain what it means when we say that the three of basic [[knowledge]], [[path]] [[knowledge]], and the [[knowledge]] of all things have no {{Wiki|real}} nature of arising. This explanation has three parts: identifying what it is we deny with {{Wiki|reasoning}} that treats the [[ultimate]]; introducing the various [[reasons]] used to deny this [[object]]; and, once we have established these two, detailing the steps to develop correct view. |

| − | The first of these has two sections of its own: a demonstration of why we must identify what it is we deny, and then the actual identification of this object. Before a person can develop within his mind that correct view which realizes emptiness, he must first identify the final object which is denied with reasoning that treats the ultimate. As the Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life states, | + | The first of these has two sections of its own: a demonstration of why we must identify what it is we deny, and then the actual identification of this [[object]]. Before a [[person]] can develop within his [[mind]] that correct [[view]] which realizes [[emptiness]], he must first identify the final [[object]] which is denied with {{Wiki|reasoning}} that treats the [[ultimate]]. As the Guide to the [[Bodhisattva’s]] Way of [[Life]] states, |

| − | Until you can find what you thought was there, | + | Until you can find what you [[thought]] was there, |

| − | You can never grasp how it cannot exist. | + | You can never [[grasp]] how it cannot exist. |

[[File:111.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:111.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Suppose that what you sought to deny was the existence of a water pitcher in a certain place. If before you started you had no mental picture of what a water pitcher looked like, you would never be able to verify with an accurate perception that it wasn’t there. Here it’s just the same. What we seek to deny is that things could really exist. If before we start we have no mental picture of what a thing that really exists would be like, then we can never have a clear idea of emptiness: the simple absence where the object that we deny isn’t there. | + | Suppose that what you sought to deny was the [[existence]] of a [[water]] pitcher in a certain place. If before you started you had no [[mental]] picture of what a [[water]] pitcher looked like, you would never be able to verify with an accurate [[perception]] that it wasn’t there. Here it’s just the same. What we seek to deny is that things could really [[exist]]. If before we start we have no [[mental]] picture of what a thing that really [[exists]] would be like, then we can never have a clear [[idea]] of [[emptiness]]: the simple absence where the [[object]] that we deny isn’t there. |

| − | Here now is the actual identification of the object we deny. Suppose something were to occur in some way that was opposite to the way that all the phenomena of physical form and so on exist deceptively. Anything that could occur this way would be precisely the final object we deny with reasoning that treats the ultimate. Therefore we must first explain how it is that all the phenomena of physical form and the rest exist deceptively. | + | Here now is the actual identification of the [[object]] we deny. Suppose something were to occur in some way that was opposite to the way that all the [[phenomena]] of [[physical]] [[form]] and so on [[exist]] deceptively. Anything that could occur this way would be precisely the final [[object]] we deny with {{Wiki|reasoning}} that treats the [[ultimate]]. Therefore we must first explain how it is that all the [[phenomena]] of [[physical]] [[form]] and the rest [[exist]] deceptively. |

| − | The second part to the discussion of how things exist deceptively consists of an explanation of the various scriptural references. First we will give a brief treatment of these references, and after that talk about how this system establishes the two truths; this latter step will include an instructive metaphor. Here now is the briefer treatment. | + | The second part to the [[discussion]] of how things [[exist]] deceptively consists of an explanation of the various scriptural references. First we will give a brief treatment of these references, and after that talk about how this system establishes the [[two truths]]; this latter step will include an instructive {{Wiki|metaphor}}. Here now is the briefer treatment. |

| − | There is a specific reason why we say that all these phenomena, physical form and the rest, exist deceptively. They are described this way because their existence is established by means of a deceptive state of mind, one which is not affected by a temporary factor that would cause it to be mistaken. | + | There is a specific [[reason]] why we say that all these [[phenomena]], [[physical]] [[form]] and the rest, [[exist]] deceptively. They are described this way because their [[existence]] is established by means of a deceptive [[state of mind]], one which is not affected by a temporary factor that would [[cause]] it to be mistaken. |

[[File:13sd.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:13sd.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | That state of mind which acts to establish the existence of physical form and other such things, and which is colored by seeing things as being real, and which is not affected by a temporary factor that would cause it to be mistaken, is only the deceptive mind. This deceptive state of mind though is not the actual grasping to real existence, for it holds its object in a way which is consistent with what the object actually is. The state of mind is deceptive in that the deceptive mind is affected by the tendency to grasp to things as being real. | + | That [[state of mind]] which acts to establish the [[existence]] of [[physical]] [[form]] and other such things, and which is colored by [[seeing]] things as [[being]] {{Wiki|real}}, and which is not affected by a temporary factor that would [[cause]] it to be mistaken, is only the deceptive [[mind]]. This deceptive [[state of mind]] though is not the actual [[grasping]] to {{Wiki|real}} [[existence]], for it holds its [[object]] in a way which is consistent with what the [[object]] actually is. The [[state of mind]] is deceptive in that the deceptive [[mind]] is affected by the tendency to [[grasp]] to things as [[being]] real. |

| − | Therefore any and every object whose existence is established by a consistent state of mind belonging to a living being who is not a Buddha is said to exist “deceptively.” The deceptive state of mind occurs by force of a deep mental seed which causes it to be mistaken; this is a seed for the tendency to grasp to things as being real, and it has been in our minds for time without beginning. This seed makes every living creature who is not a Buddha see every existing phenomenon, physical form and the rest, look as if it were a pure, discrete entity. And so we call a state of mind “deceptive” when it holds that physical form and all other things purely exist, whereas in fact they are quite the opposite: they do not purely exist. We say it is “deceptive” [Sanskrit: sawˆ vr¸ti] because such a state of mind is itself blind to the way things really are, and also because it functions in a sense to screen [Sanskrit: vr¸] or cover other things; it keeps us from seeing their suchness. | + | Therefore any and every [[object]] whose [[existence]] is established by a consistent [[state of mind]] belonging to a [[living being]] who is not a [[Buddha]] is said to [[exist]] “deceptively.” The deceptive [[state of mind]] occurs by force of a deep [[mental]] seed which [[causes]] it to be mistaken; this is a seed for the tendency to [[grasp]] to things as [[being]] {{Wiki|real}}, and it has been in our [[minds]] for [[time]] without beginning. This seed makes every living creature who is not a [[Buddha]] see every [[existing]] [[phenomenon]], [[physical]] [[form]] and the rest, look as if it were a [[pure]], discrete entity. And so we call a [[state of mind]] “deceptive” when it holds that [[physical]] [[form]] and all other things purely [[exist]], whereas in fact they are quite the opposite: they do not purely [[exist]]. We say it is “deceptive” [[[Sanskrit]]: sawˆ vr¸ti] because such a [[state of mind]] is itself blind to the way things really are, and also because it functions in a [[sense]] to screen [[[Sanskrit]]: vr¸] or cover other things; it keeps us from [[seeing]] their suchness. |

| − | So now we can define the final object which we deny by reasoning that treats the ultimate. It is any object of the mind that could exist on its side through its own unique way of being, without its existence having to be established by the fact of its appearing to a state of mind that is not impaired. This is true | + | So now we can define the final [[object]] which we deny by {{Wiki|reasoning}} that treats the [[ultimate]]. It is any [[object]] of the [[mind]] that could [[exist]] on its side through its own unique [[way of being]], without its [[existence]] having to be established by the fact of its appearing to a [[state of mind]] that is not impaired. This is true |

[[File:143kl.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:143kl.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | because the final way in which physical form and all other such phenomena exist deceptively is that they are established as existing by force of a state of mind which is not impaired by any temporary factor that would cause it to be mistaken. | + | because the final way in which [[physical]] [[form]] and all other such [[phenomena]] [[exist]] deceptively is that they are established as [[existing]] by force of a [[state of mind]] which is not impaired by any temporary factor that would [[cause]] it to be mistaken. |

| − | There is an instructive metaphor we can use for describing how physical form and other such phenomena are from our side established as existing, by the fact of their appearing to a state of mind which is not impaired; while at the same time these objects of our mind exist on their own side through their own way of being. | + | There is an instructive {{Wiki|metaphor}} we can use for describing how [[physical]] [[form]] and other such [[phenomena]] are from our side established as [[existing]], by the fact of their appearing to a [[state of mind]] which is not impaired; while at the same [[time]] these [[objects]] of our [[mind]] [[exist]] on their own side through their own way of being. |

| − | Suppose a magician is making a little piece of wood appear as a horse or cow. Seeing the piece of wood as a horse or cow comes from the side of the viewer, by the force of his own mind, as his eyes are affected by the spell of the magician. And yet the piece of wood, from its side, is appearing this way as well. Both conditions must be present. | + | Suppose a magician is making a little piece of wood appear as a [[horse]] or cow. [[Seeing]] the piece of wood as a [[horse]] or cow comes from the side of the viewer, by the force of his own [[mind]], as his [[eyes]] are affected by the spell of the magician. And yet the piece of wood, from its side, is appearing this way as well. Both [[conditions]] must be present. |

| − | There is a reason why the first condition must be present: the condition of being established from the side of the viewer, by force of his own mind, as his eyes are affected by the spell of the magician. If this condition didn’t have to be present, then a spectator whose eyes were not affected by the spell would have to see the wood appear as the animal, whereas in actuality he does not. | + | There is a [[reason]] why the first [[condition]] must be present: the [[condition]] of [[being]] established from the side of the viewer, by force of his own [[mind]], as his [[eyes]] are affected by the spell of the magician. If this [[condition]] didn’t have to be present, then a spectator whose [[eyes]] were not affected by the spell would have to see the wood appear as the [[animal]], whereas in actuality he does not. |

| − | At this same time the second condition, that the piece of wood appear from its own side as a horse or cow, must be present as well. If this condition didn’t have to be present, then the piece of wood’s appearing as a horse or cow would have to show up as well in places where there were no piece of wood, whereas in actuality it does not. | + | At this same [[time]] the second [[condition]], that the piece of wood appear from its own side as a [[horse]] or cow, must be present as well. If this [[condition]] didn’t have to be present, then the piece of wood’s appearing as a [[horse]] or cow would have to show up as well in places where there were no piece of wood, whereas in actuality it does not. |

[[File:145x.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:145x.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | In this same way are the phenomena of physical form and the rest established by force of a state of mind which is not impaired. They are labeled with names, through an unimpaired state of mind and a name which is consistent with what they are. | + | In this same way are the [[phenomena]] of [[physical]] [[form]] and the rest established by force of a [[state of mind]] which is not impaired. They are labeled with names, through an unimpaired [[state of mind]] and a [[name]] which is consistent with what they are. |

| − | They do not however exist on their side through their own unique way of being, without their existence having to be established by the fact of their appearing to a state of mind that is not impaired. If they were to exist this way, then they would have to be the ultimate way things are. And if they were, then they would have to be realized directly by a state of mind which was not mistaken; by the wisdom of a realized being who is not a Buddha, and who in a state of balanced meditation is directly realizing the way things are. In fact though they are not directly realized by such a wisdom. | + | They do not however [[exist]] on their side through their own unique [[way of being]], without their [[existence]] having to be established by the fact of their appearing to a [[state of mind]] that is not impaired. If they were to [[exist]] this way, then they would have to be the [[ultimate]] way things are. And if they were, then they would have to be [[realized]] directly by a [[state of mind]] which was not mistaken; by the [[wisdom]] of a [[realized]] [[being]] who is not a [[Buddha]], and who in a state of balanced [[meditation]] is directly [[realizing]] the way things are. In fact though they are not directly [[realized]] by such a wisdom. |

| − | Suppose a magician makes a little piece of wood appear as a horse or cow. Spectators whose eyes have been affected by his spell both see the piece of wood as a horse or cow and believe that it really is. The magician himself only sees the horse or cow; he has no belief that it is real. A spectator who arrives later, who hasn’t had the spell cast on him, neither sees the piece of wood as a horse or cow nor believes that it is. | + | Suppose a magician makes a little piece of wood appear as a [[horse]] or cow. Spectators whose [[eyes]] have been affected by his spell both see the piece of wood as a [[horse]] or cow and believe that it really is. The magician himself only sees the [[horse]] or cow; he has no [[belief]] that it is {{Wiki|real}}. A spectator who arrives later, who hasn’t had the spell cast on him, neither sees the piece of wood as a [[horse]] or cow nor believes that it is. |

| − | Three different combinations of seeing and believing exist as well with physical form and other such phenomena. The kind of people we call “common” people, those who have never had a realization of emptiness, both see and believe that form and the rest really exist. Bodhisattvas who are at one of the pure levels see phenomena as really existing during the periods following emptiness meditation; but they do not believe it. Realized beings who are not yet Buddhas, and who are in the state where they are realizing the way things are directly, neither see physical form and other such phenomena as really existing, nor do they believe that they really exist. | + | Three different combinations of [[seeing]] and believing [[exist]] as well with [[physical]] [[form]] and other such [[phenomena]]. The kind of [[people]] we call “common” [[people]], those who have never had a [[realization]] of [[emptiness]], both see and believe that [[form]] and the rest really [[exist]]. [[Bodhisattvas]] who are at one of the [[pure]] levels see [[phenomena]] as really [[existing]] during the periods following [[emptiness]] [[meditation]]; but they do not believe it. [[Realized]] [[beings]] who are not yet [[Buddhas]], and who are in the state where they are [[realizing]] the way things are directly, neither see [[physical]] [[form]] and other such [[phenomena]] as really [[existing]], nor do they believe that they really exist. |

[[File:147ages.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:147ages.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The Implication and Independent branches of the Middle Way school are identical in asserting that to exist really, to exist purely, to exist just so, to exist ultimately, and the idea where you hold that things could exist these ways are all objects which are denied by reasoning that treats the ultimate. | + | The Implication and Independent branches of the [[Middle Way]] school are identical in asserting that to [[exist]] really, to [[exist]] purely, to [[exist]] just so, to [[exist]] ultimately, and the [[idea]] where you hold that things could [[exist]] these ways are all [[objects]] which are denied by {{Wiki|reasoning}} that treats the ultimate. |

| − | The Independent branch though does not agree that to exist from its own side, to exist by nature, to exist in substance, to exist by definition, and the idea where you hold that form and other such phenomena could exist these ways are also objects which are denied by reasoning that treats the ultimate. They say that in fact anything that exists must exist these ways, with the exception of existing in substance. (There is some question though about things that are nominal.) They assert that any functional thing that exists must exist in substance. | + | The Independent branch though does not agree that to [[exist]] from its own side, to [[exist]] by nature, to [[exist]] in [[substance]], to [[exist]] by definition, and the [[idea]] where you hold that [[form]] and other such [[phenomena]] could [[exist]] these ways are also [[objects]] which are denied by {{Wiki|reasoning}} that treats the [[ultimate]]. They say that in fact anything that [[exists]] must [[exist]] these ways, with the exception of [[existing]] in [[substance]]. (There is some question though about things that are nominal.) They assert that any functional thing that [[exists]] must [[exist]] in substance. |

| − | Neither the Implication nor the Independent branches of the Middle Way school asserts that to exist as the way things are, to exist as ultimate truth, or to exist as the real nature of things is the final object which is denied by reasoning that treats the ultimate; for if something is ultimate truth, it always exists in all these three ways. | + | Neither the Implication nor the Independent branches of the [[Middle Way]] school asserts that to [[exist]] as the way things are, to [[exist]] as [[ultimate truth]], or to [[exist]] as the {{Wiki|real}} nature of things is the final [[object]] which is denied by {{Wiki|reasoning}} that treats the [[ultimate]]; for if something is [[ultimate truth]], it always [[exists]] in all these three ways. |

| Line 184: | Line 184: | ||

Reading Five: The Proofs for Emptiness | Reading Five: The Proofs for Emptiness | ||

| − | From the presentation on The Proofs for Emptiness ["The Emptiness of One or Many"] found in the Analysis of the Perfection of Wisdom, by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): | + | From the presentation on The Proofs for [[Emptiness]] ["The [[Emptiness]] of One or Many"] found in the Analysis of the [[Perfection of Wisdom]], by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): |

[[File:19gmkm.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:19gmkm.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

Here secondly is our own position. | Here secondly is our own position. | ||

| − | Consider the three: basic knowledge, path knowledge, and the knowledge of all things. | + | Consider the three: basic [[knowledge]], [[path]] [[knowledge]], and the [[knowledge]] of all things. |

They do not really exist; | They do not really exist; | ||

| − | For they exist neither as one thing which really exists, nor as many things which really exist. | + | For they [[exist]] neither as one thing which really [[exists]], nor as many things which really exist. |

They are, for example, like the reflection of a figure in a mirror. | They are, for example, like the reflection of a figure in a mirror. | ||

| − | The Jewel of the Middle Way supports this when it says, | + | The [[Jewel]] of the [[Middle Way]] supports this when it says, |

| − | The things of self and other | + | The things of [[self]] and other |

[[File:211120.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:211120.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Are free of being purely one | + | Are free of [[being]] purely one |

| − | Or being purely many, | + | Or [[being]] purely many, |

And so they have no nature: | And so they have no nature: | ||

| Line 210: | Line 210: | ||

Consider these same things. | Consider these same things. | ||

| − | They do not exist as one thing which really exists; | + | They do not [[exist]] as one thing which really exists; |

For they are things with parts. | For they are things with parts. | ||

| − | The one always implies the other, for if something existed as one thing which really exists, then it could never be a thing which appeared one way but actually existed in a different way. | + | The one always implies the other, for if something existed as one thing which really [[exists]], then it could never be a thing which appeared one way but actually existed in a different way. |

[[File:217106.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:217106.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | They do not exist as many things which really exist, because they do not exist as one thing which really exists. The one always implies the other, for many things come from bringing together a group of things that are one. | + | They do not [[exist]] as many things which really [[exist]], because they do not [[exist]] as one thing which really [[exists]]. The one always implies the other, for many things come from bringing together a group of things that are one. |

| − | The implication in the original statement is true, for if something really existed, it would have to exist either as one thing that really existed or as many things that really existed. This is always the case, for if something exists it must exist either as one or as many. | + | The implication in the original statement is true, for if something really existed, it would have to [[exist]] either as one thing that really existed or as many things that really existed. This is always the case, for if something [[exists]] it must [[exist]] either as one or as many. |

| − | Here is the “Sliver of | + | Here is the “Sliver of [[Diamond]]” {{Wiki|reasoning}}, for denying that things can come from causes: |

| − | Consider all inner and outer things that perform a function. They do not arise ultimately, For they do not arise from themselves, and they do not arise ultimately from something other than themselves, and they do not arise from both, and they do not arise without a cause. | + | Consider all inner and outer things that perform a [[function]]. They do not arise ultimately, For they do not arise from themselves, and they do not arise ultimately from something other than themselves, and they do not arise from both, and they do not arise without a cause. |

| − | These things do not arise from themselves, because they do not arise from a cause which is such that, if something were the cause, it would have to be the thing it caused. | + | These things do not arise from themselves, because they do not arise from a [[cause]] which is such that, if something were the [[cause]], it would have to be the thing it caused. |

| − | They do not arise ultimately from something which is other than themselves, for they neither arise ultimately from a cause which is other than themselves and which is unchanging, nor do they arise ultimately from a cause which is other from themselves and which is changing. | + | They do not arise ultimately from something which is other than themselves, for they neither arise ultimately from a [[cause]] which is other than themselves and which is [[unchanging]], nor do they arise ultimately from a [[cause]] which is other from themselves and which is changing. |

[[File:220d36.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:220d36.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

They do not arise ultimately from both the above, because they do not arise ultimately from either one of them individually. | They do not arise ultimately from both the above, because they do not arise ultimately from either one of them individually. | ||

| − | They do not arise without a cause, because that would be utterly absurd. The implication in the original statement is true, for if something were to arise ultimately, it would have to arise ultimately through one of the four possibilities mentioned. | + | They do not arise without a [[cause]], because that would be utterly absurd. The implication in the original statement is true, for if something were to arise ultimately, it would have to arise ultimately through one of the four possibilities mentioned. |

| − | Here is the reasoning called “The Denial that Things which Exist or Do Not Exist could Arise,” which we use for denying that things can come from results: | + | Here is the {{Wiki|reasoning}} called “The Denial that Things which [[Exist]] or Do Not [[Exist]] could Arise,” which we use for denying that things can come from results: |

| − | Consider results. They do not arise ultimately, For results which exist at the time of their cause do not arise ultimately, and results that do not exist at the time of their cause do not arise ultimately, and results that both exist and do not exist at the time of their cause do not arise ultimately, and results that neither exist nor do not exist at the time of their cause do not arise ultimately. | + | Consider results. They do not arise ultimately, For results which [[exist]] at the [[time]] of their [[cause]] do not arise ultimately, and results that do not [[exist]] at the [[time]] of their [[cause]] do not arise ultimately, and results that both [[exist]] and do not [[exist]] at the [[time]] of their [[cause]] do not arise ultimately, and results that neither [[exist]] nor do not [[exist]] at the [[time]] of their [[cause]] do not arise ultimately. |

The implication is proven in the same way as above. | The implication is proven in the same way as above. | ||

| − | Here is the reasoning known as “The Denial that Things could Arise through Any of the Four Possibilities,” which we use for denying that things can come from both causes and results: | + | Here is the {{Wiki|reasoning}} known as “The Denial that Things could Arise through Any of the Four Possibilities,” which we use for denying that things can come from both [[causes]] and results: |

[[File:221.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:221.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Consider the functional things of causes and results. They do not arise ultimately, For multiple results of multiple causes do not arise ultimately, and single results of multiple causes do not arise ultimately, and multiple results of single causes do not arise ultimately, and single results of single causes do not arise ultimately. | + | Consider the functional things of [[causes]] and results. They do not arise ultimately, For multiple results of multiple [[causes]] do not arise ultimately, and single results of multiple [[causes]] do not arise ultimately, and multiple results of single [[causes]] do not arise ultimately, and single results of single [[causes]] do not arise ultimately. |

| − | [From the Overview:] Here we will explain the fifth type of reasoning, the one based on interdependence, and known as the | + | [From the Overview:] Here we will explain the fifth type of {{Wiki|reasoning}}, the one based on [[interdependence]], and known as the “[[King]] of [[Reasons]].” First we will present the {{Wiki|reasoning}}, and then secondly prove the validity of its elements. |

Consider all inner and outer things that perform a function. | Consider all inner and outer things that perform a function. | ||

| − | They are not real, For they are interdependent. The reasoning can also be stated as: | + | They are not {{Wiki|real}}, For they are [[interdependent]]. The {{Wiki|reasoning}} can also be stated as: |

| − | Consider all inner and outer things that perform a function. They do not arise really, For they arise in dependence on other things which act as their causes and conditions. | + | Consider all inner and outer things that perform a [[function]]. They do not arise really, For they arise in dependence on other things which act as their [[causes]] and conditions. |

| − | Either way you state the reasoning, the following part should be added at the end: They are, for example, like the reflection of a figure in a mirror. This reasoning is correct, for it is spoken by the Protector [Nagarjuna]: | + | Either way you state the {{Wiki|reasoning}}, the following part should be added at the end: They are, for example, like the reflection of a figure in a [[mirror]]. This {{Wiki|reasoning}} is correct, for it is spoken by the Protector [[[Nagarjuna]]]: |

[[File:2as.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:2as.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

Anything that occurs in interdependence | Anything that occurs in interdependence | ||

| − | Is also peace in its very essence. | + | Is also [[peace]] in its very essence. |

| − | It is also proven by the Sutra Requested by Anavatapta, which states: | + | It is also proven by the [[Sutra]] Requested by [[Anavatapta]], which states: |

Anything that arises from other factors | Anything that arises from other factors | ||

| Line 270: | Line 270: | ||

Is empty. | Is empty. | ||

| − | He who understands emptiness | + | He who [[understands]] emptiness |

Acts rightly. | Acts rightly. | ||

| − | Now we will prove the various elements of this reasoning. This consists of two steps: proving the relationship between the subject and the reason, and proving the relationship between the reason and the characteristic asserted. Here is the first: | + | Now we will prove the various [[elements]] of this {{Wiki|reasoning}}. This consists of two steps: proving the relationship between the [[subject]] and the [[reason]], and proving the relationship between the [[reason]] and the [[characteristic]] asserted. Here is the first: |

| − | Consider all inner and outer things that perform a function. They are interdependent, For they consist of a label applied to their parts; they exist in dependence on their parts. | + | Consider all inner and outer things that perform a [[function]]. They are [[interdependent]], For they consist of a label applied to their parts; they [[exist]] in dependence on their parts. |

| − | The relationship between the reason and the characteristic asserted is proved as follows: | + | The relationship between the [[reason]] and the [[characteristic]] asserted is proved as follows: |

| − | If something either consists of a label applied to its parts, or exists in dependence on its parts, then it cannot be real; | + | If something either consists of a label applied to its parts, or [[exists]] in dependence on its parts, then it cannot be real; |

| − | For if something were real, neither of these two could apply to it. | + | For if something were {{Wiki|real}}, neither of these two could apply to it. |

| − | This is true because, if something were real, it would have to exist without relying on anything else. | + | This is true because, if something were {{Wiki|real}}, it would have to [[exist]] without relying on anything else. |

[[File:33015 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:33015 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Proving the relationship between the subject and the reason in the latter version of the reasoning is simple. This is how we prove the relationship between the subject and the characteristic asserted in this same version: | + | Proving the relationship between the [[subject]] and the [[reason]] in the latter version of the {{Wiki|reasoning}} is simple. This is how we prove the relationship between the [[subject]] and the [[characteristic]] asserted in this same version: |

| − | If something arises in dependence on other things which act as its causes and conditions, it cannot arise really, | + | If something arises in dependence on other things which act as its [[causes]] and [[conditions]], it cannot arise really, |

For if something were to arise really, it would have to arise without relying on anything else. | For if something were to arise really, it would have to arise without relying on anything else. | ||

| − | Both versions of the reasoning represent a type of logic where the presence of something which cannot coexist with something else is used to prove that inner and outer things which perform a function either do not exist really or do not have any nature of arising really. This is true because both of the reasons stated are such that they cannnot coexist with existing really. | + | Both versions of the {{Wiki|reasoning}} represent a type of [[logic]] where the presence of something which cannot coexist with something else is used to prove that inner and outer things which perform a [[function]] either do not [[exist]] really or do not have any nature of arising really. This is true because both of the [[reasons]] stated are such that they cannnot coexist with [[existing]] really. |

| − | There is a specific reason why we refer to this reasoning, the one based on interdependence, as the | + | There is a specific [[reason]] why we refer to this {{Wiki|reasoning}}, the one based on [[interdependence]], as the “[[King]] of [[Reasons]].” First of all, each of the other reasonings here ultimately comes down to the {{Wiki|reasoning}} of [[interdependence]]. Secondly, this {{Wiki|reasoning}} allows one to eliminate, in one step, both the extreme of permanence and the extreme of ending focussed towards this particular [[subject]] or basis of dispute. |

Reading Six: Who is Maitreya? | Reading Six: Who is Maitreya? | ||

| − | From the presentation on The Text of Maitreya found in the Overview of the Perfection of Wisdom, by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): | + | From the presentation on The Text of [[Maitreya]] found in the Overview of the [[Perfection of Wisdom]], by Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568): |

[[File:338a48773.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:338a48773.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Here is how these others make their argument. They say that “It is incorrect to relate the opening lines [of the Jewel of Realizations], the ones that are an offering of praise, to any need of the author himself. This is because Maitreya possesses no state of mind where he is aspiring to fulfill his own needs, and because the lines appear here only as a means to induce persons other than the author to follow the work.” | + | Here is how these others make their argument. They say that “It is incorrect to relate the opening lines [of the [[Jewel]] of Realizations], the ones that are an [[offering]] of praise, to any need of the author himself. This is because [[Maitreya]] possesses no [[state of mind]] where he is aspiring to fulfill his own needs, and because the lines appear here only as a means to induce persons other than the author to follow the work.” |

| − | Here secondly is our own position. It is incorrect to make the argument that appeared earlier, for such an argument only reveals that the person making it has failed to undertake exhaustive study and contemplation of the major scriptures of the greater way. How can we say this? Let us first ask the following: do you make this argument assuming that the Holy One [Maitreya] is a Buddha, or do you make it assuming that he is a bodhisattva? | + | Here secondly is our own position. It is incorrect to make the argument that appeared earlier, for such an argument only reveals that the [[person]] making it has failed to undertake exhaustive study and [[contemplation]] of the major [[scriptures]] of the greater way. How can we say this? Let us first ask the following: do you make this argument assuming that the [[Holy One]] [[[Maitreya]]] is a [[Buddha]], or do you make it assuming that he is a bodhisattva? |

| − | Suppose you say that you are making the former assumption. Doing so represents a failure to distinguish between speaking in the context of the way which is shared, the way of the perfections, and speaking in the context of the way which is not shared; that is, the way of the secret word. | + | Suppose you say that you are making the former assumption. [[Doing]] so represents a failure to distinguish between speaking in the context of the way which is shared, the way of the [[perfections]], and speaking in the context of the way which is not shared; that is, the way of the secret word. |

| − | The teaching of the secret way says that the holy Maitreya is a Buddha. This is true because—according to the secret way—Manjushri is a Buddha, and the reasons for His being so apply equally to Maitreya in every respect. | + | The [[teaching]] of the secret way says that the holy [[Maitreya]] is a [[Buddha]]. This is true because—according to the secret way—Manjushri is a [[Buddha]], and the [[reasons]] for His [[being]] so apply equally to [[Maitreya]] in every respect. |

| − | It is correct for us to say that the way of the perfections is the way which is “shared,” and that the way of the secret word is the way which is “not shared.” This is because such a description is found in a great number of authoritative works. The Steps of the Path to Buddhahood, for example, speaks about “how to train oneself in the way which is shared—the way of the perfections, and how to train oneself in the way which is not shared—the way of the secret word.” The Concise Steps as well includes the lines: | + | It is correct for us to say that the way of the [[perfections]] is the way which is “shared,” and that the way of the secret [[word]] is the way which is “not shared.” This is because such a description is found in a great number of authoritative works. The Steps of the [[Path]] to [[Buddhahood]], for example, speaks about “how to train oneself in the way which is shared—the way of the [[perfections]], and how to train oneself in the way which is not shared—the way of the secret [[word]].” The Concise Steps as well includes the lines: |

| − | Thus is the path which is shared, | + | Thus is the [[path]] which is shared, |

[[File:36.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:36.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

The one which is required | The one which is required | ||

| Line 320: | Line 320: | ||

In the higher way, | In the higher way, | ||

| − | The path which is supreme. | + | The [[path]] which is supreme. |

| − | There is another description that mentions the “way for common | + | There is another description that mentions the “way for common [[disciples]]” and the “way for unique [[disciples]].” It is apparent that these expressions, [which use the same [[Tibetan]] term,] have the same connotation as “shared” and “not shared” above. |

| − | Someone might assert that “In the context of the way of the perfections, the way of the secret word is not accepted.” This though is incorrect, for the Brief Commentary includes a section where it states that presenting the bodies of a Buddha as being exactly four is moreover not inconsistent with the way of the secret word. This section reads: “Nor moreover is this inconsistent with the other division of the teachings.” | + | Someone might assert that “In the context of the way of the [[perfections]], the way of the secret [[word]] is not accepted.” This though is incorrect, for the Brief Commentary includes a section where it states that presenting the [[bodies]] of a [[Buddha]] as [[being]] exactly four is moreover not inconsistent with the way of the secret [[word]]. This section reads: “Nor moreover is this inconsistent with the other division of the teachings.” |

[[File:425432es.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:425432es.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | There are other reasons too which prove that there is a way of the secret word. It is stated with authority that the ability to fly in the sky, and other such miraculous abilities described in the Tantra of the Garuda, occur through the power of the being who has spoken the tantra. This is true because the Commentary on Valid Perception states: | + | There are other [[reasons]] too which prove that there is a way of the secret [[word]]. It is stated with authority that the ability to fly in the sky, and other such miraculous {{Wiki|abilities}} described in the [[Tantra]] of the [[Garuda]], occur through the [[power]] of the [[being]] who has spoken the [[tantra]]. This is true because the Commentary on Valid [[Perception]] states: |

| − | There do exist the ones who know | + | There do [[exist]] the ones who know |

| − | The tantra and can in cases | + | The [[tantra]] and can in cases |

| − | Use the secret word with success; | + | Use the secret [[word]] with success; |

These are the proof. It’s mainly the power | These are the proof. It’s mainly the power | ||

| Line 340: | Line 340: | ||

And following his precepts. | And following his precepts. | ||

| − | Beyond this type of reasoning, I personally am unable to accept all the other things that people say on this point. | + | Beyond this type of {{Wiki|reasoning}}, I personally am unable to accept all the other things that [[people]] say on this point. |

[[File:542.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:542.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Here next we will demonstrate that it is also incorrect to make the argument above under the assumption that Maitreya is a bodhisattva. We ask those who make such an argument: Are we to assume then that the definition of the wish for enlightenment presented in the Ornament is a definition which is less than comprehensive? Because isn’t it true that, according to your argument, this definition would fail to cover the wish for enlightenment at the tenth bodhisattva level? | + | Here next we will demonstrate that it is also incorrect to make the argument above under the assumption that [[Maitreya]] is a [[bodhisattva]]. We ask those who make such an argument: Are we to assume then that the definition of the wish for [[enlightenment]] presented in the Ornament is a definition which is less than comprehensive? Because isn’t it true that, according to your argument, this definition would fail to cover the wish for [[enlightenment]] at the tenth [[bodhisattva]] level? |

| − | And wouldn’t this be the case, because—according to you—wouldn’t a person at the tenth bodhisattva level have fulfilled his own needs without having to stop his feeling of being satisfied with nothing more than putting a final end to the truth of suffering and the truth of its origin? | + | And wouldn’t this be the case, because—according to you—wouldn’t a [[person]] at the tenth [[bodhisattva]] level have fulfilled his own needs without having to stop his [[feeling]] of [[being]] satisfied with [[nothing]] more than putting a final end to the [[truth of suffering]] and the [[truth]] of its origin? |

| − | And wouldn’t this be the case, because—according to you—doesn’t such a person aspire to fulfill his own needs completely, and yet also fail to see that attaining the Dharma Body is necessary for him to do so? | + | And wouldn’t this be the case, because—according to you—doesn’t such a [[person]] aspire to fulfill his own needs completely, and yet also fail to see that attaining the [[Dharma Body]] is necessary for him to do so? |

| − | The above statements should help you grasp a number of crucial points. | + | The above statements should help you [[grasp]] a number of crucial points. |

| − | Realize first of all that, if something is the greater way’s wish for enlightenment, it must be linked with an associate state of mind, an aspiration to fulfill one’s own needs, which means the Dharma Body. Realize secondly that, if something is that state of mind in which one aspires to fulfill his own needs—meaning the Dharma Body—then it is a state of mind in which one aspires to fulfill his own needs. | + | Realize first of all that, if something is the greater way’s wish for [[enlightenment]], it must be linked with an associate [[state of mind]], an [[aspiration]] to fulfill one’s own needs, which means the [[Dharma Body]]. Realize secondly that, if something is that [[state of mind]] in which one aspires to fulfill his own needs—meaning the [[Dharma]] Body—then it is a [[state of mind]] in which one aspires to fulfill his own needs. |

| − | The above arguments demonstrate then that the Maitreya who authored the Ornament is a bodhisattva who has one life to go. This is true since the Mother includes a line which says, “Go and ask Maitreya there; he is a bodhisattva who has one life to go.” Moreover, the Higher Line states that Maitreya authored it in order to utilize the word of the Able One to purify himself of the obstacles to omniscience. | + | The above arguments demonstrate then that the [[Maitreya]] who authored the Ornament is a [[bodhisattva]] who has one [[life]] to go. This is true since the Mother includes a line which says, “Go and ask [[Maitreya]] there; he is a [[bodhisattva]] who has one [[life]] to go.” Moreover, the Higher Line states that [[Maitreya]] authored it in [[order]] to utilize the [[word]] of the Able One to purify himself of the obstacles to omniscience. |

[[File:56581 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:56581 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| Line 358: | Line 358: | ||

CLASS NOTES | CLASS NOTES | ||

| − | Class One: Perfection of Wisdom; the Three Jewels | + | Class One: [[Perfection of Wisdom]]; the Three Jewels |

| − | [Everything in this course is from the Svatantrika school] | + | [Everything in this course is from the [[Svatantrika]] school] |

Perfection of Wisdom | Perfection of Wisdom | ||

| − | Shakyamuni Buddha taught it for 51 years; three books remain: | + | Shakyamuni [[Buddha]] taught it for 51 years; three [[books]] remain: |

GYE DRING DU SUM | GYE DRING DU SUM | ||

| Line 370: | Line 370: | ||

long middle short three | long middle short three | ||

| − | The long sutra on Prajna Paramita Sutra has 100,000 verses | + | The long [[sutra]] on [[Prajna Paramita]] [[Sutra]] has 100,000 verses |

[[File:567.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:567.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The middle sutra has 20,000 verses | + | The middle [[sutra]] has 20,000 verses |

The short has 8,000 verses | The short has 8,000 verses | ||

| − | Together they are called YUM, or mother, because the perfection of wisdom produces all the Buddhas. | + | Together they are called YUM, or mother, because the [[perfection of wisdom]] produces all the Buddhas. |

| − | These books only remain in Tibetan. The Sanskrit libraries were burned by Moslems invading India. | + | These [[books]] only remain in [[Tibetan]]. The [[Sanskrit]] libraries were burned by Moslems invading India. |

| − | The commentary was taught by Maitreya to Asanga (~350 A.D.). The commentary on the three books above by Asanga/Maitreya is called Ornament of Realizations (short GYEN in Tibetan). It’s 50 pages in a code, so we need a commentary on this commentary. That commentary is by Haribhadra (850 A.D.), called Clarification. That one is too hard also, as is | + | The commentary was taught by [[Maitreya]] to [[Asanga]] (~350 A.D.). The commentary on the three [[books]] above by Asanga/Maitreya is called Ornament of Realizations (short GYEN in [[Tibetan]]). It’s 50 pages in a code, so we need a commentary on this commentary. That commentary is by [[Haribhadra]] (850 A.D.), called Clarification. That one is too hard also, as is |

| − | Je Tsongkhapa’s commentary (~1400). So we study the commentary by Kedrup Tempa Dargye (1493-1568), called the Analysis of the Perfection of Wisdom. | + | Je Tsongkhapa’s commentary (~1400). So we study the commentary by Kedrup Tempa Dargye (1493-1568), called the Analysis of the [[Perfection]] of Wisdom. |

| − | Definition of Prajñaparamita: - The perception of emptiness under the influence of the desire to help all sentient beings. - emptiness with love (bodhichitta). | + | Definition of [[Prajñaparamita]]: - The [[perception]] of [[emptiness]] under the [[influence]] of the [[desire]] to help all [[sentient beings]]. - [[emptiness]] with [[love]] (bodhichitta). |

| − | Realization or understanding of emptiness (wisdom) without bodhichitta isn’t perfected. Bodhichitta without understanding emptiness isn’t perfected. | + | Realization or understanding of [[emptiness]] ([[wisdom]]) without [[bodhichitta]] isn’t perfected. [[Bodhichitta]] without understanding [[emptiness]] isn’t perfected. |

[[File:60.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:60.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Arya is anyone who has direct perception of emptiness. | + | Arya is anyone who has [[direct perception]] of emptiness. |

| − | Arhant is anyone who has reached nirvana. After you perceive emptiness directly, it requires training and the application of that direct perception of emptiness to your thoughts to change the way you think and behave to reach nirvana and become an Arhant. | + | Arhant is anyone who has reached [[nirvana]]. After you perceive [[emptiness]] directly, it requires training and the application of that [[direct perception]] of [[emptiness]] to your [[thoughts]] to [[change]] the way you think and behave to reach [[nirvana]] and become an Arhant. |

| − | There are three levels of Perfection of Wisdom: | + | There are three levels of [[Perfection]] of Wisdom: |

| − | 1.) Perfection of Wisdom of the path - one who has seen emptiness directly and has bodhichitta. This person is not yet a Buddha. | + | 1.) [[Perfection of Wisdom]] of the [[path]] - one who has seen [[emptiness]] directly and has [[bodhichitta]]. This [[person]] is not yet a Buddha. |

| − | 2.) Perfection of Wisdom of the result - One who has seen emptiness directly and sees all things simultaneously as both empty and deceptive reality. Sees all past, present, and future simultaneously. This person is a Buddha. | + | 2.) [[Perfection of Wisdom]] of the result - One who has seen [[emptiness]] directly and sees all things simultaneously as both [[empty]] and deceptive [[reality]]. Sees all past, present, and future simultaneously. This [[person]] is a Buddha. |

| − | 3.) Books about Perfection of Wisdom and teachings. (The sounds of the words of the Buddha.) | + | 3.) [[Books]] about [[Perfection of Wisdom]] and teachings. (The {{Wiki|sounds}} of the words of the Buddha.) |

| − | Refuge – Buddha, Dharma, Sangha – Three Jewels | + | Refuge – [[Buddha]], [[Dharma]], [[Sangha]] – Three Jewels |

[[File:6975080 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:6975080 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | For refuge to be real, there must be: | + | For [[refuge]] to be {{Wiki|real}}, there must be: |

| − | (1) fear of suffering, i.e. wanting protection (renunciation), and | + | (1) {{Wiki|fear}} of [[suffering]], i.e. wanting protection ([[renunciation]]), and |

| − | (2) belief that something can help/protect you. Nothing in the world can protect you from suffering, except for the Three Jewels. (Called jewels because we go to them for refuge.) | + | (2) [[belief]] that something can help/protect you. [[Nothing]] in the [[world]] can protect you from [[suffering]], except for the [[Three Jewels]]. (Called jewels because we go to them for refuge.) |