Difference between revisions of "The Life of Gautama Buddha"

m (Text replacement - "Pride" to "{{Wiki|Pride}}") |

m (Text replacement - "pride" to "{{Wiki|pride}}") |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

3. For ten years the {{Wiki|Prince}} was immersed in a round of music, [[dancing]] and [[pleasure]], in the different pavilions of Spring, Autumn and Winter, but ever his [[thoughts]] reverted to the problem of [[suffering]] as he pensively tried to understand the true meaning of [[human]] [[life]]. | 3. For ten years the {{Wiki|Prince}} was immersed in a round of music, [[dancing]] and [[pleasure]], in the different pavilions of Spring, Autumn and Winter, but ever his [[thoughts]] reverted to the problem of [[suffering]] as he pensively tried to understand the true meaning of [[human]] [[life]]. | ||

| − | "Luxuries of the palace, healthy [[bodies]], [[rejoicing]] youth! what do they mean to me?" he [[meditated]]. "Some day we may be sick, we shall become aged, from [[death]] we can not eventually escape. {{Wiki|Pride}} of youth, | + | "Luxuries of the palace, healthy [[bodies]], [[rejoicing]] youth! what do they mean to me?" he [[meditated]]. "Some day we may be sick, we shall become aged, from [[death]] we can not eventually escape. {{Wiki|Pride}} of youth, {{Wiki|pride}} of health, {{Wiki|pride}} of [[existence]], all thoughtful [[people]] must cast them aside." |

"A man struggling for [[existence]] will naturally look for help. There are two ways of looking for help, a right way and a wrong way. To look the wrong way means that, while he [[recognizes]] that [[sickness]], [[old age]] and [[death]] are unavoidable, he looks for help among the same class of [[empty]], transitory things. To look the right way means that he [[recognizes]] the [[true nature]] of [[sickness]], [[old age]] and [[death]], and looks for [[life]] in that which transcends all [[human]] [[suffering]]. In this palace [[life]] of [[pleasure]] I seem to be looking for help in the wrong way." | "A man struggling for [[existence]] will naturally look for help. There are two ways of looking for help, a right way and a wrong way. To look the wrong way means that, while he [[recognizes]] that [[sickness]], [[old age]] and [[death]] are unavoidable, he looks for help among the same class of [[empty]], transitory things. To look the right way means that he [[recognizes]] the [[true nature]] of [[sickness]], [[old age]] and [[death]], and looks for [[life]] in that which transcends all [[human]] [[suffering]]. In this palace [[life]] of [[pleasure]] I seem to be looking for help in the wrong way." | ||

Revision as of 19:02, 12 September 2013

1. The Shakya clansmen dwelt along the river Rohini that flowed among the southern foothills of the Himalayas. Their King Suddhodana Gautama had transferred his capitol to Kapila and there had built a great castle and had ruled wisely, winning the joyful acclaim of his people.

The Queen's name was Maya. She was the daughter of the King's uncle who was also a king of the neighboring division of the same Shakya clan. For twenty years they had no children, then, after dreaming a strange dream of an elephant entering her side, Queen Maya became pregnant. The King and the people looked forward with joyful expectancy to the birth of a royal child. According to their custom the Queen returned to her own home for the birth, and while on the way, in the beautiful spring sunshine, she rested in the flower garden of Lumbini Park. All about her were Asoka blossoms and in delight she reached out her right arm to pluck a branch and the Prince was born. All expressed their heartfelt delight and extolled the glory of the Queen and her princely child; even Heaven and Earth manifested their joy. This memorable day was the eighth day of April. The joy of the King was extreme as he named the child: Siddhartha, which means, "Every wish fulfilled."

2. In the palace of the King, however, delight was quickly followed by sorrow, for after a few days lovely Queen Maya suddenly passed away. Fortunately her younger sister, Prajapati became the child's foster mother and brought it up with loving care.

A hermit, who lived in the mountains not far away, noticing a glory about the castle and interpreting it as a good omen, came down to the palace and was shown the child. He predicted: "This prince, if he remains in the palace after his youth, will become a great King to rule the Four Seas. But if he forsakes the household life to embrace a religious life, he will become a Buddha and the world's Savior." At first the King was pleased because of the prophecy, but later became troubled at the thought of the possibility of his only son leaving the palace to become a homeless recluse.

At the age of seven the Prince began his lessons in literature and the military arts, but his thoughts more naturally ran to other things. One spring day he went out of the castle with his father and they were watching a farmer at his plowing; he noticed a bird flying down to the ground and carrying away a little worm which had been thrown out of the ground by the farmer's plough. He who had lost his mother so soon after his birth, was deeply affected by the tragedy of these two little creatures. He sat down in the shade of a tree and thought about it, whispering to himself:

"Alas! Do all living creatures kill each other?"

This spiritual wound was deepened day after day as he grew up; like a little scar on a young tree, the sufferings of human life were more and more deeply carved into his mind.

The King was increasingly worried as he recalled the hermit's prophecy and tried in every possible way to cheer the Prince and to turn his thoughts in other directions. At the age of nineteen, the King arranged the marriage of the Prince to the Princess Yasodhara, who was the daughter of Suprabuddha, Lord of Koliya castle and a brother of the late Queen Maya.

3. For ten years the Prince was immersed in a round of music, dancing and pleasure, in the different pavilions of Spring, Autumn and Winter, but ever his thoughts reverted to the problem of suffering as he pensively tried to understand the true meaning of human life.

"Luxuries of the palace, healthy bodies, rejoicing youth! what do they mean to me?" he meditated. "Some day we may be sick, we shall become aged, from death we can not eventually escape. Pride of youth, pride of health, pride of existence, all thoughtful people must cast them aside."

"A man struggling for existence will naturally look for help. There are two ways of looking for help, a right way and a wrong way. To look the wrong way means that, while he recognizes that sickness, old age and death are unavoidable, he looks for help among the same class of empty, transitory things. To look the right way means that he recognizes the true nature of sickness, old age and death, and looks for life in that which transcends all human suffering. In this palace life of pleasure I seem to be looking for help in the wrong way."

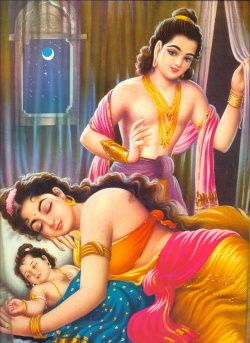

4. Thus the mental struggle went on in the mind of the Prince until his twenty-ninth year when his only child, Rahula, was born. This seemed to bring things to a climax and he decided to leave his palace home and seek the solution of his mental unrest in the homeless life of a mendicant. This plan he carried out one night, by leaving the castle with only his personal servant, Channa, and his favorite horse, the snow-white Kanthaka, and even these he left behind him when he had crossed the river at the b ounds of his Father's kingdom.

But his mental troubles were not at an end and many doubts beset him. "Perhaps it would be better for me to return to the castle and seek some other solution; then the whole world will be mine." But he resisted these doubts by realizing that nothing worldly could satisfy him. So he shaved his head, carried a begging bowl in his hand, and turned his mendicant steps to the south.

The Prince first visited the hermit Bhagava and watched his ascetic practices; then he went successively to Arada Kalama and Udraka Ramaputra to learn their methods of attainment, but after practicing them for a time became convinced that they would not lead him to enlightenment. Finally he went to the Magadha country and practiced asceticism in the forest of Uruvilva on the banks of the Nairanjana river where it flows by the Gaya Castle.

5. The methods of his practice were unbelievably intense. He spurred himself on with the thought that "no ascetic in the past, none in the present, and none in the future, ever have or ever will practice more earnestly that I do."

Still, the Prince could not get what he sought. After six years in the forest he gave up the practice of asceticism. He bathed in the river and accepted a bowl of food from the hand of Sujata, a maid who lived in the neighboring village. The five companions who had lived with the Prince for the six years of his ascetic practices looked on with amazement that he could receive food from the hand of a maiden; they thought him degraded thereby and left him. The Prince, thus, was left alone. He was still feeble but at the risk of his life he attempted a final meditation, saying to himself, "Blood may become exhausted, flesh may decay, bones may fall apart, but I will never leave this place until I find the way to enlightenment."

It was an intense and incomparable struggle! His mind was desperate, was filled with confusing thoughts, dark shadows overhung his spirit, he was beset with all the lures of evil. But carefully and patiently he examined them one by one and rejected them all. It, indeed, was a hard struggle, that made his blood run thin, his flesh creep, and his bones crack. But when the morning star appeared in the eastern sky, the struggle was over and the Prince's mind was as clear and bright as the day-break. He had found the path to enlightenment at last. It was December the 8th, when he was thirty-five years of age that the Prince became Buddha.

6. From this time on the Prince was known by different names; some spoke of him as Buddha, the Perfectly Enlightened One; some spoke of him as Shakyamuni, the Sage of the Shakya clan; and still others spoke of him affectionately as the Blessed One. He went first to Mrigadava in Varanasi where the five mendicants who had lived with him during the six years of his ascetic life were staying. At first they shunned him, but after he had talked with them, they believed in him and became his first followers. Then he went to Rajagriha castle and won over King Bimbisara who had always been his friend.

From there he went about the country living on alms and persuading men to accept his way of life, and men responded to him as thirsty men seek water and hungry men seek food. Two great teachers, Sariputra and Maudgalyayana, and their two thousand disciples came to him. At first the Buddha's Father, King Suddhodana, suffering inwardly from his son's retirement, held aloof, but afterward became his faithful disciple; and Maha-Prajapati, the Buddha's step-mother, and the Princess Yasodhara, his wife, and all the members of the Shakya clan, believed in him and followed him. And multitudes of others became his devoted and faithful followers.

7. For forty-five years the Buddha went about the country preaching and persuading men to follow his way of life, but at last, at Vaisali on the way from Rajagriha to Sravasti, he became ill and predicted that after three months he would enter Nirvana. Still he journeyed on until he reached Pava where he was made critically ill by food offered by Cunda, a blacksmith. Then by easy stages in spite of great pain and weakness, he reached the forest on the border of Kuninagara castle. Lying between two large sala trees, he continued his teachings to his favorite disciples until the last moment. Thus passed into the unknown the greatest of the world's teachers and the kindest of men.

8. Under the oversight of Ananda, the Buddha's favorite disciple, the body was cremated by his friends in Kusinagara castle. Seven of the neighboring rulers under the lead of King Ajatasatru demanded that the ashes be divided among them. The King of the Kunsinagara castle at first refused and the dispute even threatened to end in war, but by the advice of a wise man named Dona, the crises passed and the ashes were divided and buried under eight great monuments. Even the embers of the fire and the earthen jar that had held the ashes were divided and given to two others to be likewise honored.