Difference between revisions of "Hossō"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

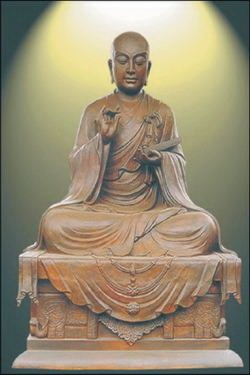

[[File:Xuanzang478.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang478.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | Hossō is one of the six [[schools of Buddhism]] during the {{Wiki|Nara period}} in [[Japan]] and one of three schools (the other two {{Wiki|being}} [[Kegon]] and [[Ritsu]] schools) which have survived till this day. Hossō in [[Japanese]] {{Wiki|literature}} is the school of the [[characteristics of dharma]]. It is the continuation of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Faxian]] school which in turn was based on the [[Yogacarya]] school of [[India]]. The school was transmitted to [[Japan]] by [[Japanese]] scholar-monks who studied in [[China]] with [[Faxian]] [[masters]] such as the [[monk]] [[Xuanzang]] (Jp. Genjo) and K’uei-chi (Jp. {{Wiki|Kuiji}}), and became one of the most {{Wiki|powerful}} of the six {{Wiki|Nara}} schools. | + | [[Hossō]] is one of the six [[schools of Buddhism]] during the {{Wiki|Nara period}} in [[Japan]] and one of three schools (the other two {{Wiki|being}} [[Kegon]] and [[Ritsu]] schools) which have survived till this day. [[Hossō]] in [[Japanese]] {{Wiki|literature}} is the school of the [[characteristics of dharma]]. It is the [[continuation]] of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Faxian]] school which in turn was based on the [[Yogacarya]] school of [[India]]. The school was transmitted to [[Japan]] by [[Japanese]] scholar-monks who studied in [[China]] with [[Faxian]] [[masters]] such as the [[monk]] [[Xuanzang]] (Jp. Genjo) and K’uei-chi (Jp. {{Wiki|Kuiji}}), and became one of the most {{Wiki|powerful}} of the six {{Wiki|Nara}} schools. |

| − | The [[Yogācāra]] schools are based on early [[Indian]] [[Buddhist thought]] by [[masters]] such as the brothers [[Asaṅga]] and [[Vasubandhu]] (380-450AD), and are also known as “[[consciousness only]]” since their [[doctrine]] stresses that all [[phenomena]] are [[phenomena]] of the [[mind]]. The [[doctrine]] of [[consciousness-only]] reduces all [[existence]] to one hundred [[dharmas]] (or factors) in five divisions, namely, [[mind]], [[mental]] [[function]], {{Wiki|material}}, not associated with [[mind]] and [[unconditioned]] [[dharma]]. Contrary to common [[perception]], [[Yogācāra]] thinkers placed heavy emphasis on [[consciousness]] not because they subscribe to the [[idea]] that [[consciousness]] has [[ultimate reality]] ([[Yogācāra]] claims [[consciousness]] is only conventionally {{Wiki|real}} since it arises from moment to moment due to fluctuating [[causes]] and [[conditions]]), but rather because [[consciousness]] is the [[cause]] of the [[karma]] which they were seeking to weed out (Lusthaus, 2007) [[Yogācāra]] [[tradition]] expounds that the [[mind]] distorts [[reality]] and projects it as [[reality]] itself (Tagawa, 2009). In the [[Yogācāra]] [[tradition]], the [[mind]] is divided into the [[Eight Consciousnesses]] and the Four Aspects of [[Cognition]] which produce what we [[view]] as [[reality]] (Zim, 1995). | + | The [[Yogācāra]] schools are based on early [[Indian]] [[Buddhist thought]] by [[masters]] such as the brothers [[Asaṅga]] and [[Vasubandhu]] (380-450AD), and are also known as “[[consciousness only]]” since their [[doctrine]] stresses that all [[phenomena]] are [[phenomena]] of the [[mind]]. The [[doctrine]] of [[consciousness-only]] reduces all [[existence]] to one hundred [[dharmas]] (or factors) in five divisions, namely, [[mind]], [[mental]] [[function]], {{Wiki|material}}, not associated with [[mind]] and [[unconditioned]] [[dharma]]. Contrary to common [[perception]], [[Yogācāra]] thinkers placed heavy emphasis on [[consciousness]] not because they subscribe to the [[idea]] that [[consciousness]] has [[ultimate reality]] ([[Yogācāra]] claims [[consciousness]] is only {{Wiki|conventionally}} {{Wiki|real}} since it arises from moment to moment due to fluctuating [[causes]] and [[conditions]]), but rather because [[consciousness]] is the [[cause]] of the [[karma]] which they were seeking to weed out ([[Lusthaus]], 2007) [[Yogācāra]] [[tradition]] expounds that the [[mind]] distorts [[reality]] and projects it as [[reality]] itself (Tagawa, 2009). In the [[Yogācāra]] [[tradition]], the [[mind]] is divided into the [[Eight Consciousnesses]] and the Four Aspects of [[Cognition]] which produce what we [[view]] as [[reality]] (Zim, 1995). |

| − | Therefore, the [[philosophy]] of Hossō was also known as Yuishiki, or ‘[[consciousness-only]]’, [[because of]] its fundamental [[belief]] that all of [[reality]], including both the [[objective]] [[world]] and the subjective [[mind]] that regards it, are but evolutions of [[consciousness]] according to [[karma]]. The {{Wiki|Discourse}} on the {{Wiki|Theory}} of [[Consciousness-Only]] (Jo yuishikiron) is an important text for the Hossō school in [[Japan]]. [[Lankavatara Sutra]] is also a very important text of the [[Japanese]] Hossō school. | + | Therefore, the [[philosophy]] of [[Hossō]] was also known as [[Yuishiki]], or ‘[[consciousness-only]]’, [[because of]] its fundamental [[belief]] that all of [[reality]], including both the [[objective]] [[world]] and the subjective [[mind]] that regards it, are but evolutions of [[consciousness]] according to [[karma]]. The {{Wiki|Discourse}} on the {{Wiki|Theory}} of [[Consciousness-Only]] (Jo yuishikiron) is an important text for the [[Hossō]] school in [[Japan]]. [[Lankavatara Sutra]] is also a very important text of the [[Japanese]] [[Hossō]] school. |

{{Wiki|History}} of [[Yogācāra School]] in [[China]] | {{Wiki|History}} of [[Yogācāra School]] in [[China]] | ||

[[File:Xuanzang79.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xuanzang79.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The {{Wiki|movement}} that would eventually [[form]] the Hossō school in [[Japan]] was initiated in [[China]] by [[Xuanzang]] around 630AD. [[Xuanzang]], the founder of the [[Faxian]] school was among the famous [[scholars]] who made [[pilgrimages]] to [[India]] to study [[Buddhist texts]] during the sixth and seventh centuries AD. [[Xuanzang]] travelled overland to [[India]] through perilous bandit-ridden deserts and treacherous mountains and studied at the renowned [[Nalanda]] [[monastic]] {{Wiki|university}} in [[India]]. He brought back with him to [[China]] volumes of [[Buddhist texts]] which he later translated to {{Wiki|Chinese}}. Among the important texts are the ‘[[Consciousness-only]]’ texts (Tagawa, 2009) | + | The {{Wiki|movement}} that would eventually [[form]] the [[Hossō]] school in [[Japan]] was initiated in [[China]] by [[Xuanzang]] around 630AD. [[Xuanzang]], the founder of the [[Faxian]] school was among the famous [[scholars]] who made [[pilgrimages]] to [[India]] to study [[Buddhist texts]] during the sixth and seventh centuries AD. [[Xuanzang]] travelled overland to [[India]] through perilous bandit-ridden deserts and treacherous [[mountains]] and studied at the renowned [[Nalanda]] [[monastic]] {{Wiki|university}} in [[India]]. He brought back with him to [[China]] volumes of [[Buddhist texts]] which he later translated to {{Wiki|Chinese}}. Among the important texts are the ‘[[Consciousness-only]]’ texts (Tagawa, 2009) |

| − | • The Samdhinirmocana [[Sūtra]] | + | • The [[Samdhinirmocana]] [[Sūtra]] |

• The Yogācārabhūmi-śastra composed by [[Nagarjuna]] (there is much [[scholarly]] [[debate]] on the origins of this text which some say is attributed to [[Asaṅga]]). | • The Yogācārabhūmi-śastra composed by [[Nagarjuna]] (there is much [[scholarly]] [[debate]] on the origins of this text which some say is attributed to [[Asaṅga]]). | ||

| − | • The Mahāyānasaṃgrāha composed by [[Asaṅga]] | + | • The [[Mahāyānasaṃgrāha]] composed by [[Asaṅga]] |

| − | These, with government support and many assistants, he translated into {{Wiki|Chinese}}, in addition to [[writing]] the influential text, the [[Cheng Weishi Lun]] ({{Wiki|Discourse}} on the {{Wiki|Theory}} of [[Consciousness-only]] or commonly referred to as Wei-shi), which became another core text of the {{Wiki|East Asian}} branches of [[Yogācāra]] [[thought]]. [[Xuanzang]] was also instrumental in promoting devotional, [[meditative]] practices toward [[Maitreya]], the [[future Buddha]], thus leading to a common association of the [[Consciousness-only school]] and that [[deity]]. Xuanzang’s [[disciple]], {{Wiki|Kuiji}} (one of the founders of the Hossō school) wrote a number of important commentaries on the [[Yogācāra]] texts and further developed the [[influence]] of this [[doctrine]] in [[China]] and was [[recognized]] by later {{Wiki|adherents}} as the first true patriach of the school (Lusthaus, -). In [[time]], the [[Faxian]] school in [[Chinese Buddhism]] [[died]] out due to competition with more native {{Wiki|Chinese}} schools of [[thought]] such as [[Tiantai]] and [[Huayan]] and later with more popular sects/schools such as [[Chan]] and [[Pure Land]]. However, the {{Wiki|tenets}} of the [[Yogācāra]] school in [[China]] was eventually absorbed into these later schools which heavily relied on its translations, commentaries and concepts (Tagawa, 2009). | + | These, with government support and many assistants, he translated into {{Wiki|Chinese}}, in addition to [[writing]] the influential text, the [[Cheng Weishi Lun]] ({{Wiki|Discourse}} on the {{Wiki|Theory}} of [[Consciousness-only]] or commonly referred to as Wei-shi), which became another core text of the {{Wiki|East Asian}} branches of [[Yogācāra]] [[thought]]. [[Xuanzang]] was also instrumental in promoting devotional, [[meditative]] practices toward [[Maitreya]], the [[future Buddha]], thus leading to a common association of the [[Consciousness-only school]] and that [[deity]]. [[Xuanzang’s]] [[disciple]], {{Wiki|Kuiji}} (one of the founders of the [[Hossō]] school) wrote a number of important commentaries on the [[Yogācāra]] texts and further developed the [[influence]] of this [[doctrine]] in [[China]] and was [[recognized]] by later {{Wiki|adherents}} as the first true [[patriach]] of the school ([[Lusthaus]], -). In [[time]], the [[Faxian]] school in [[Chinese Buddhism]] [[died]] out due to competition with more native {{Wiki|Chinese}} schools of [[thought]] such as [[Tiantai]] and [[Huayan]] and later with more popular sects/schools such as [[Chan]] and [[Pure Land]]. However, the {{Wiki|tenets}} of the [[Yogācāra]] school in [[China]] was eventually absorbed into these later schools which heavily relied on its translations, commentaries and [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] (Tagawa, 2009). |

[[Yogācāra]] in [[Korea]] and [[Japan]] | [[Yogācāra]] in [[Korea]] and [[Japan]] | ||

| − | The [[Faxian]] teachings were transmitted to [[Korea]] as Beopsang and [[Japan]] as Hossō where they made considerable impact. The Beopsang teachings did not last long as a {{Wiki|distinct}} school in [[Korea]] and like [[China]]; its teachings were frequently assimilated into later schools of [[thought]] (Tagawa, 2009). | + | The [[Faxian]] teachings were transmitted to [[Korea]] as Beopsang and [[Japan]] as [[Hossō]] where they made considerable impact. The Beopsang teachings did not last long as a {{Wiki|distinct}} school in [[Korea]] and like [[China]]; its teachings were frequently assimilated into later schools of [[thought]] (Tagawa, 2009). |

| − | The Hossō School was brought to [[Japan]] by the [[Japanese]] [[monk]] [[Dosho]] (629-700AD). He went to [[China]] in 653AD and became a student of [[Xuanzang]] (596/600-664AD) for ten years. Back in [[Japan]], [[Dosho]] propagated the Hossō [[teaching]] at the Guan-go-ji [[monastery]]. His first student was Gyogi (667-748AD). The [[lineage]] founded by him was called the [[transmission]] of the teachings of the Southern [[Monastery]]. | + | The [[Hossō]] School was brought to [[Japan]] by the [[Japanese]] [[monk]] [[Dosho]] (629-700AD). He went to [[China]] in 653AD and became a student of [[Xuanzang]] (596/600-664AD) for ten years. Back in [[Japan]], [[Dosho]] propagated the [[Hossō]] [[teaching]] at the Guan-go-ji [[monastery]]. His first student was Gyogi (667-748AD). The [[lineage]] founded by him was called the [[transmission]] of the teachings of the Southern [[Monastery]]. |

[[File:Xwf.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Xwf.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | In 716 the [[monk]] [[Gembo]] went to [[China]] and became a student of the [[Faxian]] [[master]] Chih-chou. [[Gembo]] also remained for ten years. After his return to [[Japan]] in 735, he taught at the Kobuku-ji [[monastery]]. His student was Genju, who propagated the line of the [[teaching]] represented by [[Gembo]]. This line of [[transmission]] is known as that of the Northern [[Monastery]]. It is generally considered to be the {{Wiki|orthodox}} line. The Hossō School never flourished in [[Japan]] to the extent that its counterparts had in [[India]] and [[China]]. | + | In 716 the [[monk]] [[Gembo]] went to [[China]] and became a student of the [[Faxian]] [[master]] [[Chih-chou]]. [[Gembo]] also remained for ten years. After his return to [[Japan]] in 735, he taught at the Kobuku-ji [[monastery]]. His student was Genju, who propagated the line of the [[teaching]] represented by [[Gembo]]. This line of [[transmission]] is known as that of the Northern [[Monastery]]. It is generally considered to be the {{Wiki|orthodox}} line. The [[Hossō]] School never flourished in [[Japan]] to the extent that its counterparts had in [[India]] and [[China]]. |

| − | The Hossō sect still [[exists]] in [[Japan]] to this day, surviving long after it [[died]] out in [[Korea]] and [[China]] but its [[influence]] has diminished since the centre of [[Buddhist]] authority moved away from {{Wiki|Nara}} and with the rise of the [[Ekayana]] [[schools of Buddhism]] ([[Tendai]], [[Zen]], [[Pure Land]], etc.) (Tagawa, 2009). There were frequent [[debates]] between [[scholars]] of the Hossō school and other [[emerging]] schools during the {{Wiki|Nara period}}. The founders of [[Shingon]] [[Buddhism]], [[Kūkai]] (774-835AD), and [[Tendai]] [[Buddhism]], [[Saichō]] (767-822AD) exchanged letters of [[debate]] with Hossō [[scholar]] Tokuitsu (Abe, 1999) Hossō [[scholars]] were particularly at odds with [[Saichō]] but maintained amicable relations with the [[Shingon]] [[esoteric]] school and even adopted some of their practices. | + | The [[Hossō]] sect still [[exists]] in [[Japan]] to this day, surviving long after it [[died]] out in [[Korea]] and [[China]] but its [[influence]] has diminished since the centre of [[Buddhist]] authority moved away from {{Wiki|Nara}} and with the rise of the [[Ekayana]] [[schools of Buddhism]] ([[Tendai]], [[Zen]], [[Pure Land]], etc.) (Tagawa, 2009). There were frequent [[debates]] between [[scholars]] of the [[Hossō]] school and other [[emerging]] schools during the {{Wiki|Nara period}}. The founders of [[Shingon]] [[Buddhism]], [[Kūkai]] (774-835AD), and [[Tendai]] [[Buddhism]], [[Saichō]] (767-822AD) exchanged letters of [[debate]] with [[Hossō]] [[scholar]] [[Tokuitsu]] (Abe, 1999) [[Hossō]] [[scholars]] were particularly at odds with [[Saichō]] but maintained amicable relations with the [[Shingon]] [[esoteric]] school and even adopted some of their practices. |

| − | The proponents of other schools like the [[Jōdo]] Shū [[Pure Land]] school such as [[Hōnen]] derived their early [[Buddhist]] [[philosophical]] foundation from Hossō [[scholars]] in their early [[monastic]] [[education]]. After completing his [[monastic]] training, [[Hōnen]] later went on to refute the [[philosophy]] by [[debating]] with Hossō [[scholars]]. Jōkei, a Hossō [[scholar]] and one of Hōnen’s toughest critics frequently refuted his teachings, while simultaneously striving to make [[Buddhism]] more accessible to the common [[people]] (much like [[Hōnen]] did) by reviving devotion to [[Maitreya Bodhisattva]] and placing emphasis on the benefits of [[rebirth]] in the [[Tusita Heaven]], rather than the [[Pure Land]] of [[Amitabha]] (Ford, 2009). Jōkei is also a leading figure in the efforts to revive [[monastic]] [[discipline]] at places like Toshodaiji, Kofukuji and counted other notable [[monks]] among his [[disciples]], including Eison who founded the Shingon-Vinaya sect (Ford J. L., 2006). | + | The proponents of other schools like the [[Jōdo]] [[Shū]] [[Pure Land]] school such as [[Hōnen]] derived their early [[Buddhist]] [[philosophical]] foundation from [[Hossō]] [[scholars]] in their early [[monastic]] [[education]]. After completing his [[monastic]] training, [[Hōnen]] later went on to refute the [[philosophy]] by [[debating]] with [[Hossō]] [[scholars]]. [[Jōkei]], a [[Hossō]] [[scholar]] and one of Hōnen’s toughest critics frequently refuted his teachings, while simultaneously striving to make [[Buddhism]] more accessible to the common [[people]] (much like [[Hōnen]] did) by reviving [[devotion]] to [[Maitreya Bodhisattva]] and placing emphasis on the benefits of [[rebirth]] in the [[Tusita Heaven]], rather than the [[Pure Land]] of [[Amitabha]] (Ford, 2009). [[Jōkei]] is also a leading figure in the efforts to revive [[monastic]] [[discipline]] at places like [[Toshodaiji]], [[Kofukuji]] and counted other notable [[monks]] among his [[disciples]], including [[Eison]] who founded the Shingon-Vinaya sect (Ford J. L., 2006). |

REFERENCES | REFERENCES | ||

-. (-). [[Life]] of [[Honen]], [[Jodo Shu]] homepage Homepage. Retrieved from http://www.jodo.org/about_hs/ho_life.html. Retrieved 2009-07-01. | -. (-). [[Life]] of [[Honen]], [[Jodo Shu]] homepage Homepage. Retrieved from http://www.jodo.org/about_hs/ho_life.html. Retrieved 2009-07-01. | ||

Abe, R. (1999). The Weaving of [[Mantra]]: [[Kūkai]] and the Construction of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Discourse}}. Columbia {{Wiki|University}} Press. | Abe, R. (1999). The Weaving of [[Mantra]]: [[Kūkai]] and the Construction of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Discourse}}. Columbia {{Wiki|University}} Press. | ||

Ford, J. (2009). Chapter 6: [[Buddhist]] Ceremonials (Kōshiki) and the Ideological {{Wiki|Discourse}} of Established [[Buddhism]] in {{Wiki|Medieval}} [[Japan]]”. in Payne, Richard K.; Leighton, Taigen Dan. {{Wiki|Discourse}} and Ideology in {{Wiki|Medieval}} [[Japanese Buddhism]]. Routledge. | Ford, J. (2009). Chapter 6: [[Buddhist]] Ceremonials (Kōshiki) and the Ideological {{Wiki|Discourse}} of Established [[Buddhism]] in {{Wiki|Medieval}} [[Japan]]”. in Payne, Richard K.; Leighton, Taigen Dan. {{Wiki|Discourse}} and Ideology in {{Wiki|Medieval}} [[Japanese Buddhism]]. Routledge. | ||

| − | Ford, J. L. (2006). Jokei and [[Buddhist]] Devotion in Early {{Wiki|Medieval}} [[Japan]]. US: Oxford {{Wiki|University}} Press. | + | Ford, J. L. (2006). Jokei and [[Buddhist]] [[Devotion]] in Early {{Wiki|Medieval}} [[Japan]]. US: {{Wiki|Oxford}} {{Wiki|University}} Press. |

| − | Lusthaus, D. (2007). Quick Overview of the Faxiang School 法相宗. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://www.acmuller.net/yogacara/schools/faxiang.html | + | [[Lusthaus]], D. (2007). Quick Overview of the [[Faxiang School]] [[法相宗]]. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://www.acmuller.net/yogacara/schools/faxiang.html |

| − | Lusthaus, D. (-). What is and is not [[Yogacara]]? Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dan_Lusthaus | + | [[Lusthaus]], D. (-). What is and is not [[Yogacara]]? Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dan_Lusthaus |

| − | Sho, K. (2002). The Elementary-Level Textbook: Part 1: Gosho Study “[[Letter]] To The Brothers”. SGI-USA Study Curriculum. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://www.sgi-usa.org/buddhism/library/SokaGakkai/Study/Elementary/Text1.htm | + | Sho, K. (2002). The Elementary-Level Textbook: Part 1: Gosho Study “[[Letter]] To The Brothers”. SGI-USA Study {{Wiki|Curriculum}}. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://www.sgi-usa.org/buddhism/library/SokaGakkai/Study/Elementary/Text1.htm |

Tagawa, S. (2009).Muller, C. Ed. Living [[Yogācāra]]: An Introduction to [[Consciousness-Only]] [[Buddhism]]. [[Wisdom Publications]]. | Tagawa, S. (2009).Muller, C. Ed. Living [[Yogācāra]]: An Introduction to [[Consciousness-Only]] [[Buddhism]]. [[Wisdom Publications]]. | ||

| − | Zim, R. (1995). Basic [[ideas]] of [[Yogacara]] [[Buddhism]]. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from San Francisco State {{Wiki|University}}: http://online.sfsu.edu/~rone/Buddhism/Yogacara/basicideas.htm | + | Zim, R. (1995). Basic [[ideas]] of [[Yogacara]] [[Buddhism]]. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from {{Wiki|San Francisco}} State {{Wiki|University}}: http://online.sfsu.edu/~rone/Buddhism/Yogacara/basicideas.htm |

Prepared by: | Prepared by: | ||

Revision as of 05:05, 15 February 2014

Hossō is one of the six schools of Buddhism during the Nara period in Japan and one of three schools (the other two being Kegon and Ritsu schools) which have survived till this day. Hossō in Japanese literature is the school of the characteristics of dharma. It is the continuation of the Chinese Faxian school which in turn was based on the Yogacarya school of India. The school was transmitted to Japan by Japanese scholar-monks who studied in China with Faxian masters such as the monk Xuanzang (Jp. Genjo) and K’uei-chi (Jp. Kuiji), and became one of the most powerful of the six Nara schools.

The Yogācāra schools are based on early Indian Buddhist thought by masters such as the brothers Asaṅga and Vasubandhu (380-450AD), and are also known as “consciousness only” since their doctrine stresses that all phenomena are phenomena of the mind. The doctrine of consciousness-only reduces all existence to one hundred dharmas (or factors) in five divisions, namely, mind, mental function, material, not associated with mind and unconditioned dharma. Contrary to common perception, Yogācāra thinkers placed heavy emphasis on consciousness not because they subscribe to the idea that consciousness has ultimate reality (Yogācāra claims consciousness is only conventionally real since it arises from moment to moment due to fluctuating causes and conditions), but rather because consciousness is the cause of the karma which they were seeking to weed out (Lusthaus, 2007) Yogācāra tradition expounds that the mind distorts reality and projects it as reality itself (Tagawa, 2009). In the Yogācāra tradition, the mind is divided into the Eight Consciousnesses and the Four Aspects of Cognition which produce what we view as reality (Zim, 1995).

Therefore, the philosophy of Hossō was also known as Yuishiki, or ‘consciousness-only’, because of its fundamental belief that all of reality, including both the objective world and the subjective mind that regards it, are but evolutions of consciousness according to karma. The Discourse on the Theory of Consciousness-Only (Jo yuishikiron) is an important text for the Hossō school in Japan. Lankavatara Sutra is also a very important text of the Japanese Hossō school.

History of Yogācāra School in China

The movement that would eventually form the Hossō school in Japan was initiated in China by Xuanzang around 630AD. Xuanzang, the founder of the Faxian school was among the famous scholars who made pilgrimages to India to study Buddhist texts during the sixth and seventh centuries AD. Xuanzang travelled overland to India through perilous bandit-ridden deserts and treacherous mountains and studied at the renowned Nalanda monastic university in India. He brought back with him to China volumes of Buddhist texts which he later translated to Chinese. Among the important texts are the ‘Consciousness-only’ texts (Tagawa, 2009)

• The Samdhinirmocana Sūtra

• The Yogācārabhūmi-śastra composed by Nagarjuna (there is much scholarly debate on the origins of this text which some say is attributed to Asaṅga).

• The Mahāyānasaṃgrāha composed by Asaṅga

These, with government support and many assistants, he translated into Chinese, in addition to writing the influential text, the Cheng Weishi Lun (Discourse on the Theory of Consciousness-only or commonly referred to as Wei-shi), which became another core text of the East Asian branches of Yogācāra thought. Xuanzang was also instrumental in promoting devotional, meditative practices toward Maitreya, the future Buddha, thus leading to a common association of the Consciousness-only school and that deity. Xuanzang’s disciple, Kuiji (one of the founders of the Hossō school) wrote a number of important commentaries on the Yogācāra texts and further developed the influence of this doctrine in China and was recognized by later adherents as the first true patriach of the school (Lusthaus, -). In time, the Faxian school in Chinese Buddhism died out due to competition with more native Chinese schools of thought such as Tiantai and Huayan and later with more popular sects/schools such as Chan and Pure Land. However, the tenets of the Yogācāra school in China was eventually absorbed into these later schools which heavily relied on its translations, commentaries and concepts (Tagawa, 2009).

Yogācāra in Korea and Japan

The Faxian teachings were transmitted to Korea as Beopsang and Japan as Hossō where they made considerable impact. The Beopsang teachings did not last long as a distinct school in Korea and like China; its teachings were frequently assimilated into later schools of thought (Tagawa, 2009).

The Hossō School was brought to Japan by the Japanese monk Dosho (629-700AD). He went to China in 653AD and became a student of Xuanzang (596/600-664AD) for ten years. Back in Japan, Dosho propagated the Hossō teaching at the Guan-go-ji monastery. His first student was Gyogi (667-748AD). The lineage founded by him was called the transmission of the teachings of the Southern Monastery.

In 716 the monk Gembo went to China and became a student of the Faxian master Chih-chou. Gembo also remained for ten years. After his return to Japan in 735, he taught at the Kobuku-ji monastery. His student was Genju, who propagated the line of the teaching represented by Gembo. This line of transmission is known as that of the Northern Monastery. It is generally considered to be the orthodox line. The Hossō School never flourished in Japan to the extent that its counterparts had in India and China.

The Hossō sect still exists in Japan to this day, surviving long after it died out in Korea and China but its influence has diminished since the centre of Buddhist authority moved away from Nara and with the rise of the Ekayana schools of Buddhism (Tendai, Zen, Pure Land, etc.) (Tagawa, 2009). There were frequent debates between scholars of the Hossō school and other emerging schools during the Nara period. The founders of Shingon Buddhism, Kūkai (774-835AD), and Tendai Buddhism, Saichō (767-822AD) exchanged letters of debate with Hossō scholar Tokuitsu (Abe, 1999) Hossō scholars were particularly at odds with Saichō but maintained amicable relations with the Shingon esoteric school and even adopted some of their practices.

The proponents of other schools like the Jōdo Shū Pure Land school such as Hōnen derived their early Buddhist philosophical foundation from Hossō scholars in their early monastic education. After completing his monastic training, Hōnen later went on to refute the philosophy by debating with Hossō scholars. Jōkei, a Hossō scholar and one of Hōnen’s toughest critics frequently refuted his teachings, while simultaneously striving to make Buddhism more accessible to the common people (much like Hōnen did) by reviving devotion to Maitreya Bodhisattva and placing emphasis on the benefits of rebirth in the Tusita Heaven, rather than the Pure Land of Amitabha (Ford, 2009). Jōkei is also a leading figure in the efforts to revive monastic discipline at places like Toshodaiji, Kofukuji and counted other notable monks among his disciples, including Eison who founded the Shingon-Vinaya sect (Ford J. L., 2006).

REFERENCES

-. (-). Life of Honen, Jodo Shu homepage Homepage. Retrieved from http://www.jodo.org/about_hs/ho_life.html. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

Abe, R. (1999). The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press.

Ford, J. (2009). Chapter 6: Buddhist Ceremonials (Kōshiki) and the Ideological Discourse of Established Buddhism in Medieval Japan”. in Payne, Richard K.; Leighton, Taigen Dan. Discourse and Ideology in Medieval Japanese Buddhism. Routledge.

Ford, J. L. (2006). Jokei and Buddhist Devotion in Early Medieval Japan. US: Oxford University Press.

Lusthaus, D. (2007). Quick Overview of the Faxiang School 法相宗. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://www.acmuller.net/yogacara/schools/faxiang.html

Lusthaus, D. (-). What is and is not Yogacara? Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dan_Lusthaus

Sho, K. (2002). The Elementary-Level Textbook: Part 1: Gosho Study “Letter To The Brothers”. SGI-USA Study Curriculum. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://www.sgi-usa.org/buddhism/library/SokaGakkai/Study/Elementary/Text1.htm

Tagawa, S. (2009).Muller, C. Ed. Living Yogācāra: An Introduction to Consciousness-Only Buddhism. Wisdom Publications.

Zim, R. (1995). Basic ideas of Yogacara Buddhism. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from San Francisco State University: http://online.sfsu.edu/~rone/Buddhism/Yogacara/basicideas.htm

Prepared by:

Karma Tashi Choedron