Difference between revisions of "The I-Ching and the Theories of David Bohm"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

In 1951, the American {{Wiki|quantum physicist}} {{Wiki|David Bohm}} (1917-1992), wrote a textbook entitled {{Wiki|Quantum Theory}}. In it he presented a clear account of the {{Wiki|orthodox}}, Copenhagen interpretation of {{Wiki|quantum physics}}, which was formulated in the 1920s by Danish {{Wiki|physicist}} Niels Bohr and the {{Wiki|German}} {{Wiki|Werner Heisenberg}}; it is still highly influential today. | In 1951, the American {{Wiki|quantum physicist}} {{Wiki|David Bohm}} (1917-1992), wrote a textbook entitled {{Wiki|Quantum Theory}}. In it he presented a clear account of the {{Wiki|orthodox}}, Copenhagen interpretation of {{Wiki|quantum physics}}, which was formulated in the 1920s by Danish {{Wiki|physicist}} Niels Bohr and the {{Wiki|German}} {{Wiki|Werner Heisenberg}}; it is still highly influential today. | ||

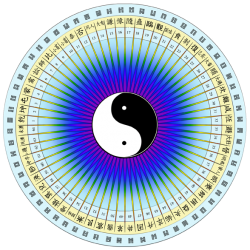

[[File:CircleHexChart 72.png|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:CircleHexChart 72.png|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | But even before Bohm's [[book]] was published, he began to have [[doubts]] about the assumptions underlying the {{Wiki|conventional}} approach. He had difficulty accepting that subatomic particles had no [[objective]] [[existence]] and took on definite properties only when {{Wiki|physicists}} tried to | + | But even before Bohm's [[book]] was published, he began to have [[doubts]] about the assumptions underlying the {{Wiki|conventional}} approach. He had difficulty accepting that subatomic particles had no [[objective]] [[existence]] and took on definite properties only when {{Wiki|physicists}} tried to observe and [[measure]] them. He also had difficulty believing that the {{Wiki|quantum}} [[world]] was characterized by [[absolute]] {{Wiki|indeterminism}} and chance, and that things just happened for no [[reason]] whatsoever. |

He began to suspect that there might be deeper [[causes]] behind the apparently random and crazy nature of the subatomic [[world]]. | He began to suspect that there might be deeper [[causes]] behind the apparently random and crazy nature of the subatomic [[world]]. | ||

Revision as of 11:43, 14 December 2013

In 1951, the American quantum physicist David Bohm (1917-1992), wrote a textbook entitled Quantum Theory. In it he presented a clear account of the orthodox, Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics, which was formulated in the 1920s by Danish physicist Niels Bohr and the German Werner Heisenberg; it is still highly influential today.

But even before Bohm's book was published, he began to have doubts about the assumptions underlying the conventional approach. He had difficulty accepting that subatomic particles had no objective existence and took on definite properties only when physicists tried to observe and measure them. He also had difficulty believing that the quantum world was characterized by absolute indeterminism and chance, and that things just happened for no reason whatsoever.

He began to suspect that there might be deeper causes behind the apparently random and crazy nature of the subatomic world.

Following the model of David Bohm, the Tao (Chinese: 道 Dao) resembles his explicate order (the physical universe we call "reality") and what he calls implicate order (the unlimited world of future potentialities and possibilities out of which reality manifests).

Tao is often translated as "the Way" or "the Path". It is the principle of change and becoming; it decides the defining modalities of reality and what in the not yet manifest realm of future possibilities as a potential reality holds. This also explains why Richard Wilhelm choose to translate Tao with "the Meaning" - the British Sinologist James Legge (1815-1897) chose the Greek philosophical term "Logos" - to illustrate that the way of all becoming, being and passing away is not random at all, but follows patterns established by the Tao.