Difference between revisions of "The Teachings of the Nyingma Tradition"

| Line 221: | Line 221: | ||

[[Vows]] of [[Pratimoksa]] | [[Vows]] of [[Pratimoksa]] | ||

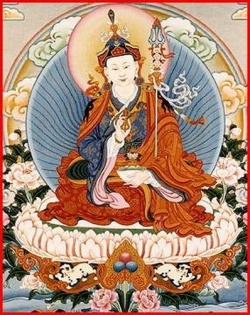

[[File:Nyingma_Refuge_Treehava-2.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Nyingma_Refuge_Treehava-2.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Pious attendants ([[shravaka]]) who seek to enter the stream to [[enlightenment]] and eventually to become [[arhats]] are required to | + | Pious attendants ([[shravaka]]) who seek to enter the stream to [[enlightenment]] and eventually to become [[arhats]] are required to observe a number of [[vows]] conductive to [[individual liberation]], the [[pratimoksha]], from [[rebirth]] in [[cyclic existence]]. Such [[precepts]] include (1) short-term [[vows]] that are taken by [[laymen]] and [[laywomen]] (for a single day) entailing abstinence from killing, {{Wiki|sexual}} misconduct, [[stealing]], lying, [[alcohol]], frivolous [[activities]], eating after lunch, and using high seats or beds; (2) lifelong [[vows]] taken by devout [[laymen]] or [[laywomen]] which require one not to kill, lie, steal, be {{Wiki|intoxicated}}, or commit {{Wiki|sexual}} misconduct; (3) lifelong [[vows]] taken by [[novice]] [[monks]] or [[nuns]], which include ten rules of training and [[thirty-three]] subsidiary restrictive rules; (4) the [[vows]] of a probationary [[nun]], which include six basic [[precepts]] and six ancillary [[precepts]]; (5) the two-hundred and fifty-three [[vows]] taken by a fully [[ordained]] [[monk]]; and (6) the three hundred and sixty [[four vows]] maintained by fully [[ordained]] [[nuns]]. |

The majority of these [[vows]] [[concern]] deportment, dress, {{Wiki|sexual}} abstinence, eating, drinking, walking, [[sleeping]] arrangements, and other modes of daily regimen, which are all deemed appropriate for renunciates. There are also the [[vows]] of abstinence from the “four defeats:” murder, {{Wiki|sexual}} misconduct, [[stealing]] and lying. Some advanced renunciates may additionally practice the so-called twelve [[ascetic]] [[virtues]], which entail further restrictions on [[diet]], attire and residence. | The majority of these [[vows]] [[concern]] deportment, dress, {{Wiki|sexual}} abstinence, eating, drinking, walking, [[sleeping]] arrangements, and other modes of daily regimen, which are all deemed appropriate for renunciates. There are also the [[vows]] of abstinence from the “four defeats:” murder, {{Wiki|sexual}} misconduct, [[stealing]] and lying. Some advanced renunciates may additionally practice the so-called twelve [[ascetic]] [[virtues]], which entail further restrictions on [[diet]], attire and residence. | ||

Revision as of 11:35, 14 December 2013

This essay provides a traditional Nyingma presentation of the Buddhist Teachings. It first describes the nine-vehicle doxography of the teachings. It then gives a standard explanation of the two modes of transmission as understood by the Nyingma tradition: Kama (bka’ ma, or “spoken word”) and terma (gter ma, or “treasure”).

I. Nine Vehicles of the Teachings

The Nyingma tradition classifies the teachings of the Buddha according to a system of nine vehicles, or yanas. The yanas do not said to represent separate altogether different approaches; instead each of them is a step toward the next, which naturally includes the preceding ones. According to the Nyingma, the highest teaching is that of Atiyoga, or Dzogchen (rdzogs chen).

Before summarizing the main features of each of the nine vehicles, it is useful to first establish the distinction between worldly or mundane vehicles, which cannot take the practitioner beyond samsara, and supramundane vehicles, which can lead first to freedom from samsara and, ultimately, to enlightenment.

Worldly Vehicles

There are two kinds of worldly or mundane vehicles which, according to their result, are considered to be unmistaken or mistaken. The first is the “vehicle followed by human and celestial beings” (lha mi thegs pa). It allows rebirth in the highest forms of existence within samsara but cannot deliver from samsara altogether. A brief summary of its view, meditation, and fruit follows:

View: The practitioner acknowledges the suffering of the lower realms of samsara and recognizes the laws of karma, of cause and effect (that negative acts will inevitably bring suffering and positive acts happiness), and the existence of past and future rebirths. In this respect the practitioner’s understanding is considered to be correct. The aim, however, is limited to avoiding rebirth in the lower realms and gaining rebirth as a human being or as one of the three kinds of celestial beings.

Meditation: Striving to reach this goal, one practices the four contemplations (bsam gtan) and merges with the four formless states.

Action: To achieve this, the ten non-virtuous actions (killing, stealing, and sexual misconduct; telling lies, slandering, gossiping, and speaking harsh words; envy, ill will, and erroneous views) are avoided. Their opposites are actively practiced: the ten virtuous acts, while cultivating loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity (known as the four boundless thoughts).

Fruit: According to the strength of the meditation and the extent of her virtuous deeds, the practitioner will take rebirth in any of the higher realms of samsara from the human realm up to the realm of formless gods.

Some followers of the second kind of worldly vehicles, the mistaken ones, thoroughly lack understanding and ignore the karmic laws of cause and effect. The nihilists have the wrong understanding in their assumption that there are no past and future lives. They are principally concerned with seeking power and pleasure in this present life. The eternalists also have mistaken views such as thinking that there is a permanent, independent, all-powerful creator, himself without cause, who decides the fate of beings and who produces impermanent phenomena despite being permanent himself. In short, the followers of these vehicles lack the views and means effective for achieving liberation.

The Supramundane Vehicles

The supramundane, or Nine Vehicles, are comprised of the three vehicles of the sutras – those of the Sravakas, the Pratyekabuddhas and the Bodhisattvas – and the six tantric vehicles of Kriya, Upa, Yoga, Mahayoga, Anuyoga, and Atiyoga tantras. The nine can also be grouped into three vehicles: 1) the Hinayana, which includes the first two; 2) the Mahayana, comprising the third, and 3) the Vajrayana, which includes the last six.

In the Nine Vehicles the practitioner takes the support of the Three Jewels – the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha – and trains in ethical discipline, concentrated meditationd penetrating insight, which can deliver one from the bonds of samsara.

1) Hinayana

The Hinayana path is based on renunciation that is motivated by the wish to liberate solely oneself from samsara. When considered on its own it may be called the “lesser vehicle;” when integrated into the whole path of the three vehicles, it is regarded as the “fundamental vehicle.”

The sravakas

A sravaka (literally, a “listener”) is someone who fears the sufferings of samsara. Concerned chiefly with his own liberation, he listens to the teachings of the Buddha, realizes the suffering inherent in all conditioned phenomena, and meditates upon the Four Noble Truths: suffering, the cause of suffering (the negative emotions), the extinction of suffering, and the path to attain this extinction.

View: A sravaka understands that there is no truly existent self inherent in an individual, but maintains that other phenomena have a real basis in indivisible particles and moments of consciousness that he holds to be truly existent. Such views define the Vaibhasika school.

Meditation: Steeping himself in flawless ethics and lay or monastic self-discipline, the practitioner listens to the teachings, ponders their meaning, and assimilates this meaning through meditation. Applying antidotes, such as considering the unpleasant aspects of objects of desire, he conquers the negative emotions (klesas) and attains inner calm (samatha). Then, by cultivating insight (vipasyana) he comes to understand that an individual possesses no truly existent, independent self.

Action: The practitioner performs the twelve ascetic virtues and acts chiefly to achieve personal liberation.

Fruit: Beginning with the stage of “stream-enterer,” and continuing with the stages of “once-returner” (he who will be reborn only one more time) and of “non-returner” (he who will no longer be reborn in samsara), the practitioner liberates himself and eventually becomes an arhat, “one who has destroyed his foe”, the negative emotions.

The pratyekabuddhas

A pratyekabuddha, “who became Buddha by himself,” can attain the level of an arhat without relying upon a teacher in this lifetime (though teachers have been met in former lifetimes). He meditates on dependent origination, the natural process through which everything appears through the combination of interdependent causes and conditions. No phenomenon can appear without a cause or can it be made by a permanent creator that himself is without cause.

Acquainting himself with the fact of death, this practitioner becomes weary of the condition of samsara. Pondering the causes of suffering and death, he investigates the twelve links of dependent origination to find that the misery of samsara originates in ignorance and further develops through grasping.

View: Though realizing that individuals and indivisible particles of matter are devoid of true existence, he still clings to moments of consciousness as constituting real entities. Thus, he realizes fully the selflessness of the individual and only partly the selflessness of phenomena. This view characterizes the Sautrantika School.

Meditation: The practitioner contemplates the twelve interdependent links in reverse order: seeing bones in a cemetery, he reflects upon death (12th link) and understands that it follows old age, which itself is caused by birth (11th). Birth results from the drive to exist (10th), which arises from grasping (9th), which rises from craving (8th), which arises from feeling (7th), which arises from contact (6th), which arises from the six senses (5th), which arise from name and form (4th) which arise from consciousness (3rd), which arises from karmic dispositions (2nd), which arise from ignorance (1st). Finally, following the chain from ignorance to death, the pratyekabuddha understands definitively that ignorance, the clinging to phenomena as real, is the source of all suffering in samsara.

Action and Fruit: Because he is practicing for his own, limited deliverance, the pratyekabuddha does not teach others verbally, but nonetheless inspires faith in them through the display of miracles, such as flying through the sky or transforming the upper half of his body into fire and the lower half into water, and so on. Eventually he becomes an arhat. Since sravakas and pratyekabuddhas practice primarily for their own sakes, they cannot attain complete buddhahood and benefit innumerable sentient beings, as does a Bodhisattva.

2) Mahayana

The Mahayana practitioner is motivated by the altruistic intention to liberate others from suffering and bring them to buddhahood. The Mahayana, or Great Vehicle, surpasses the Hinayana in many essential aspects. A bodhisattva recognizes the lack of true existence of both the individual and of all phenomena. Vowing to attain enlightenment for the sake of others, he develops limitless compassion for all suffering beings. This compassion, when united with perfect wisdom, inflames the realization of emptiness (shunyata). The view of emptiness is not a form of nihilism, but the understanding that all phenomena are devoid of an autonomous, permanent, true existence.

Having examined phenomena and recognized their empty nature, the bodhisattva regards everything as being like a dream or an illusion. However, this understanding of absolute truth does not cause him to ignore relative truth. With loving-kindness and compassion he keeps his actions in perfect accord with the karmic laws of cause and effect and works tirelessly to benefit beings. Realizing the ultimate nature of phenomena and the mind, and free from all clinging and conceptual fabrications, he rests in the great evenness of the non-dual, absolute truth.

View: The view is correct understanding of the lack of reality of both the individual and all phenomena. Various levels of the understanding of this view and the definitions of the absolute and the relative truth are found in the Mahayana schools of Cittamatra (Mind Only) and Madhyamaka (Middle Way).

The Cittamatrin says that all phenomena are the short or long-term products of mind and are therefore unreal. However, it postulates that, in terms of absolute truth, self-cognizant, non-dual awareness truly does exist.

The Madhyamaka has two main schools: Svatantrika and Prasangika. The first one posits that, in terms of absolute truth, phenomena have no true existence whatsoever. In terms of relative truth, however, phenomena appear through the combination of causes and conditions, perform their functions, and have a verifiable conventional existence.

The second school asserts that from both an absolute and a relative point of view phenomena are totally devoid of existence and cannot be characterized by any concept such as “existent,” “nonexistent,” “both existent and nonexistent,” or “neither existent nor nonexistent.” For the Prasangikas, absolute truth is the non-dual pristine wisdom of the buddhas, free from any conceptual elaboration.

Meditation: On the four “paths of learning” the thirty-seven branches of enlightenment is practiced. Having recognized that the potential for achieving buddhahood, the tathagatagarbha, is present within, the practitioner aspires to reach enlightenment. Through inner-calm meditation (samatha) he pacifies all clinging to outer perceptions and develops a serene concentration (samadhi).

Through insight meditation (vipasyana) he ascertains that all outer phenomena are unreal, illusory, and that all inner clinging and dualistic notions of subject-object are devoid of reality. According to the Great Middle Way, by being free from regarding things as real and resting in the evenness of the absolute nature in which there is nothing to subtract and nothing to add. Inner-calm and insight are perfectly united.

Action: In post-meditation the practitioner benefits others by regarding them as dearer than herself. The six paramitas – generosity, discipline, patience, diligence, meditationd insight – are practiced, enhanced by skillful means, strength, prayer, and pristine wisdom, thus defining ten paramitas altogether. When these all become permeated with wisdom, they are transmuted from ordinary virtues into transcendent activities.

Fruit: Eventually, when a Bodhisattva attains the path of “no more learning” and the eleventh spiritual level, or bhumi, she becomes a fully enlightened Buddha. Having fulfilled her own aspirations by realizing the dharmakaya (the absolute body), she manifests the rupakaya (the body of form which includes the sambhogakaya, the body of supreme enjoyment, and the nirmanakaya, the manifested body) for the sake of others and acts compassionately for their benefit until the end of samsara.

3) Vajrayana

The Vajrayana path is based on “pure perception” and motivated by the aspiration to swiftly free oneself and others from delusion through the application of skillful means. The tantras and their related vehicles are categorized into three outer and three inner tantras, according to the level of view, meditation, and fruit.

The Mahayana chiefly considers that the buddha-nature is present in every sentient being like a seed, or potentiality. The Vajrayana regards this nature to be already fully present as wisdom or pristine awareness – the undiluted and fundamental nature of mind. Therefore, while the former vehicles are known as “causal vehicles,” the Vajrayana is known as the “resultant vehicle.” As it is said, “In the causal vehicles one recognizes the nature of mind as the cause of buddhahood; in the resultant vehicle one regards the nature of mind as buddhahood itself.”

Since the “result” of the path, buddhahood, is primordially present, one only needs to actualize it or remove the veils that mask it. The Vajrayana is also said to be unobscured by narrow understanding, to provide many skillful means, to be without hardship, and intended for beings who possess the highest faculties.

The Madhyamaka philosophy considers relative truth to be false, impure, and devoid of true existence. The Vajrayana, however, makes use of relative truth by regarding phenomena as the unlimited display of primordial purity. The six classes of Vajrayana tantras teach this in an increasingly direct and profound way.

The gateway to the Vajrayana is the empowerment, or abhiseka, which is given by the spiritual master. It empowers the recipient to practice the Vajrayana teachings and to subsequently achieve ordinary and supreme spiritual attainments, or siddhi.

According to Nyingma religious history, the Buddha gave teachings on the Vajrayana such as the Kalachakra and Guhyasamaja to a few highly evolved individuals. He predicted in many scriptures that this teaching would later spread further, and that proceeding masters such as Saraha, the Eighty Mahasiddhas, the Eight Vidyadharas, and particularly Padmasambhava, would receive and spread these teachings.

This path is considered to be for the students with the highest spiritual capacities and therefore in Ancient India it was practiced in utmost secrecy. In Tibet, however, it was practiced openly. Hence a great heritage of Vajrayana philosophy, practice, and culture came from Tibet.

In the Vajrayana, as in all Buddhist teachings, there are the two aspects of the mediatation – shamata or calm abiding and vipashyana or higher perspective. In the Vajrayana these aspects are referred to as “the two stages.” Vajrayana shamata is known as utpattikrama, od “development stage” and involves focusing on the characteristics of deities and mandalas through visualization. The Vajrayana vipashyana, known as sampannakrama, or “completion stage,” involves resting the mind in the simplicity of wisdom’s clarity. In the Nyingma tradition these two stages are sought to be practiced in unity.

These two stages make use of visualizations using thangkas, deities, and mandalas, as well as ceremonies which employ dance and music.

The Three Outer Tantras

Tantra literally means continuity. This refers to the continuity of the absolute nature that pervades all phenomena and to the continuity of the primordial, luminous nature of mind. In general, the word tantra refers to the texts that teach the Vajrayana and also to the view, meditationd action that these texts express.

The three outer tantras refer to three classes of scriptures and to the related practices known as Kriya, Upa, and Yoga.

Kriya

Although the practitioner has gained some understanding of absolute truth, in the realm of relative truth he still seeks accomplishment as something to be gained from outside. Kriya tantra practice or tantra of activity emphasizes ritual cleanliness: cleanness of the mandala and the sacred substances, as well as the cleanliness of the practitioner who performs ablutions, changes clothes three times a day, and eats the three white and the three sweet foods. (milk, curd, butter, sugar, honey, and molasses).

View: The view is based on the two truths. Absolute truth is the wisdom of the mind’s ultimate nature that is pure, luminous, and void. It is free of the four limiting concepts: existence, nonexistence, appearance, and emptiness. Relative truth may be viewed in two ways. According to the Madhyamaka it is completely fictitious; according to the view of the tantras, since phenomena are perceived as constituting the mandala of enlightened deities, relative truth is naturally perfect.

Meditation: The practitioner usually visualizes himself in his ordinary form. He regards the deity that is the object of meditation as a lord and requests to be granted siddhi in the same way as a servant or subject would supplicate a master. The contemplation of absolute truth, without any specific object of focus, is also practiced.

Action: Action focuses on cleanliness, concentration, and mantra recitation.

Fruit: Realization of the Three Kayas and Five Wisdoms of perfect buddhahood is attained in seven human lifetimes.

Upa

Upa, or practice tantra, is also called Ubhayatantra, dual-tantra, because it combines the view of the next vehicle, Yoga tantra, with the action, or conduct, of Kriya tantra, the former one. The abhiseka consists of the empowerment of the Five Buddha Families. Realization may be gained in five lifetimes.

Yoga

The Yoga tantra, or tantra of union with the nature, is thus called because it emphasizes inner practice more than outer conduct. The abhiseka given here is the same as that of Upa but with the addition of the blessing of the vajra master.

View: In regard to absolute truth the practitioner realizes the non-conceptual, ultimate nature and its expression – luminosity. As result of this realization, within the context of perfect relative truth, phenomena appear as the “mandala of adamantine space” (vajradhatu mandala).

Meditation: During formal meditation the practitioner visualizes himself as a deity and invites from the buddhafield a wisdom deity similar in form to himself, who usually remains in the space before the practitioner. The relationship between the deity and the practitioner is one of equals or friends. During objectless meditatione practitioner merges his perception of phenomena with the absolute nature beyond characteristics and rests in evenness. Phenomena are thus seen as the play of wisdom manifesting as deities.

Action: The practitioner still strives for accomplishment through achieving the “good” and eschewing the “bad.” Chief importance is given to the yoga of the deity and the practitioner strives to benefit others.

Fruit: Realization is attained in three lifetimes.

The Three Inner Tantras

There are three inner tantras. Mahayoga is like the ground or basis. All phenomena are recognized as the magical display of mind-as-such, of the indivisible union of emptiness and appearances. Anuyoga is like the path. It allows us to realize that phenomena are the non-dual manifestation of space and primordial wisdom. Atiyoga is like the fruit and allows us to realize the natural presence of primordial wisdom, beyond beginning and ending.

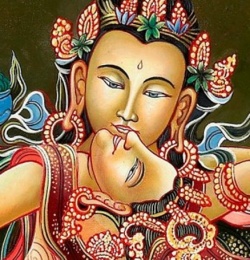

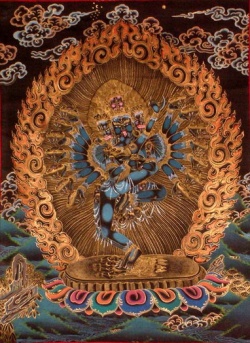

The general view of the inner tantras is to see all phenomena as being primordially perfect and to unite realization of the “great purity” with that of the “great evenness.” Deities are visualized in union, symbolizing the indivisibility of emptiness and compassion, wisdom and means. The wisdom nature of the deity is considered to be inseparable from our own buddha- nature. Action transcends accepting and rejecting. The fruit is buddhahood in one lifetime.

Maha

Mahayoga is called the “great yoga” because it brings realization of non-duality. Its gateway consists of four main empowerments: the vase, the secret, the wisdom, and the symbolic (or word) empowerment. These purify the defilements of the body, speech and mind, as well as their subtle obscurations, and enable the practitioner to realize the Four Kayas, respectively.

View: Awareness, free from conceptual limitations, is regarded as absolute truth and inherently endowed with all enlightened qualities. All phenomena – the outer universe, the various psychophysical elements of the body as well as thoughts – arise as a mandala which stands for relative truth. The two truths – emptiness and phenomena – are inseparable, like gold and its color.

Meditation: Mahayoga emphasizes the development stage which focuses on the process of visualization. The practitioner sees herself as a deity who is the very manifestation of her own wisdom nature. The outer world is seen as a buddhafield and the beings therein as male and female deities. These methods help the practitioner to recognize the primordial, unchanging purity of phenomena that is the true condition of all things.

The practitioner also engages in the completion stage that is related to the subtle channels (nadi), energy (prana), and essence (bindu). Formless meditation involves merging the mind with the profound, absolute nature.

Action: With confidence cultivated through skillful means such as devotion and pure perception, without rejection or attachment the practitioner uses samsaric experience as a catalyst to foster the practice.

Fruit: Realization is attained within this lifetime or in the ensuing bardo, the transitional state between death and rebirth.

Anu

Anuyoga emphasizes the practice of the completion stage and the understanding of the mandala as being contained within our own vajra-body. Having realized the non-duality of the expanse of emptiness and pristine wisdom, the practitioner attains accomplishment through “union” and “liberation.” Anuyoga is called the “ensuing yoga” because it focuses on the path of the transmutation of desire into wisdom that follows the experience of bliss. Its gateway, the empowerment, is comprised of thirty-six sections.

View: All phenomena are understood as the play of our own mind. The uncreated aspect of mind, transcending all conditions, is called the “immaculate expanse of the mother Samantabhadri,” the mandala of primordial nature. Its all-pervading and unobstructed manifestation, whichis mind's self-display, is the “wisdom father Samantabhadra,” the naturally present mandala.

These two aspects have the same nature. They are referred to as the “child of great bliss,” in which the absolute expanse and pristine wisdom are united, representing the indivisible nature of all mandalas.

Meditation: The practitioner uses the path of skillful means that focuses on the channels, energies, and vital essences of the vajra-body. Practicing the yogas of the “upper door” and the “lower door,” leads to swift realization of inherent wisdom.

The practitioner also practices the Path of Liberation without elaboration. Having merged with the depth of non-conceptual simplicity, without intentional meditatione lets everything remain in the absolute nature, just as it is. In formal, elaborate practice, through uttering a mantra once, the mandala with its deities arises instantly with perfect clarity, like a fish leaping out of water.

Action: The action here primarily involves resting in evenness. There are also three actions spoken of: the “sky-like action” that comes through realizing the non-duality of the absolute expanse of emptiness and pristine wisdom; the “king-like action,” also called the “action resembling wood burning in a bonfire,” which comes through mastering the five poisons as five wisdoms; the “uninterrupted, river-like action” that comes through realizing the sameness of samsara and nirvana.

Fruit: Within one lifetime, the practitioner actualizes the Body of Great Bliss that embodies the Four Kayas.

Ati

The extraordinary feature of Atiyoga is that the practitioner maintains lucid recognition of the ultimate nature of mind: pure, vividly clear, perfect in itself. It is luminosity that is naturally present, self-existing primordial wisdom, without any alteration or fabrication, beyond taking or rejecting, hope and fear.

This is the “ultimate yoga,” far surpassing all the lower vehicles that entail striving, fabrication, and effort. Atiyoga is also known as Dzogchen, the Great Perfection, meaning that all phenomena are naturally perfect in their primordial purity.

Its gateway is the empowerment of the “creative power of awareness.” According to the Secret Heart Essence, the practitioner receives four empowerments: elaborate, unelaborate, very unelaborate, and utterly unelaborate.

View: All phenomena within both samsara and nirvana are perfect in primordial buddhahood, the great sphere of Dharmakaya, the self-existing pristine wisdom beyond searching and effort.

Atiyoga has three classes. The first is meant for individuals who are concerned with the workings of mind, the second is intended for individuals whose minds are like the sky, and the third is for individuals whose temperaments transcend all effort.

According to the mind-class, all perceived phenomena are none other than the play of mind-as-such, the inexpressible, self-existing wisdom.

According to the space-class, self-existing wisdom and all phenomena sprung from its continuum never stray from the expanse of Samantabhadri. They have always been pure and liberated.

According to the most extraordinary of the three, the class of pith instructions, regarding the true nature of samsara and nirvana there are no obscurations to be rid of and no enlightenment to be acquired. To realize this allows an instantaneous arising of the self-existing wisdom beyond intellect.

Meditation: In the mind-class, having recognized that all phenomena are the indescribable Dharmakaya, the self-existing wisdom, the practitioner rests in the continuum of the awareness-void in which there is nothing to illuminate, nothing to reject, and nothing to add. The enlightened mind is like infinite space, its potential for manifestation is like a mirror, and limitless illusory phenomena are like multifarious reflections in that mirror. Since everything arises as the play of the enlightened mind, there is no need to obstruct the arising of thoughts. The practitioner simply remains in the natural condition of mind-as-such.

In the space-class, having recognized that all phenomena never leave the expanse of Samantabhadri and are primordially pure and free, the practitioner abides in the continuum of the ultimate nature without targets, effort, or searching. There is no need to use antidotes: being void, thoughts and perceptions vanish by themselves. Phenomena are like stars naturally arrayed as ornaments in the firmament of the absolute nature. There is no need to consider, as is done in the mind-class, that they arise as the play of awareness. Everything is the infinite expanse of primordial liberation.

In the class of pith instructions, having recognized that mind-as-such is primordially pure emptiness, we practice trekcho (khregs chod), leaving mind and all phenomena in their natural state of pristine liberation. Trekcho, “cutting through hardness (or concreteness),” refers to breaking through the solidity of mental clinging. Then, having discovered the naturally present mandala of the body, togal (thod rgal) is practiced and the very face of the naturally present luminosity, the pristine wisdom that dwells within, is seen.

Without leaning toward the “clarity” aspect of the mind-class or toward the “void” aspect of the space-class, without considering the self-liberation of thoughts (as in the mind-class) or the way of letting them be in emptiness (as in the space-class), the practitioner simply rests with unaltered simplicity in the confident realization of primordial purity that is inexpressible, beyond intellect, and of which phenomena are the natural radiance.

Two extraordinary practices are found only in the teachings of the Great Perfection. Togal, or, “direct leap,” refers to going directly to the highest point of realization. These two are related respectively to primordial purity and spontaneous presence. It is said that the first eight vehicles use mind as the path, and that only the ninth one uses awareness as the path.

Action: Since everything that arises is the play of the absolute nature, the practitioner acts within the continuum of non-dual evenness, without taking and rejecting, free from clinging and fixation.

Fruit: The practitioner dwells directly on the level of the Ever-perfect, Samantabhadra. Since outer phenomena have been mastered, they are realized as infinite buddhafields; since the inner aggregates of the illusory body have been mastered, this body can turn into radiant light; having mastered the innermost expanse of awareness, the practitioner puts an end to delusion. There is neither hope of attaining buddhahood, nor fear of falling into samsara. As it is said:

The fruit of the Great Perfection

Is primordially present as the Buddha nature.

It does not need to be obtained:

It is ripe within oneself.

As said above, the nine vehicles do not represent separate paths. Each of them is a step toward the next; all vehicles ultimately culminate in the Great Perfection.

The Three Vows

The practice of the nine vehicles involves vows, preceptsd commitments. There are many divisions to these, but, in essence, they fall under three sets of vows: 1.The Pratimoksa Vows of the Hinayana contain all the lay and monastic precepts of ethical conduct taught by the Buddha in the Vinaya. Discipline and strict maintenance of the vows protect the mind from conditions that generate negativity and emotional entanglements. 2. The Bodhisattva Vows of the Mahayana are embodied in the generation, cultivation, and preservation of bodhicitta. This vow is to dedicate all thoughts, words, and actions toward the benefit of others and to lead all beings to complete enlightenment. 3. The Samayas are the precepts and commitments of the Vajrayana. These formalize the all-important bonds with the guru, fellow disciples, and spiritual practice.

The various vehicles or pathways presented within the Buddhist teachings are often considered in terms of their philosophical views, meditative techniques and outward activities. The taking of vows, or samvara, or commitments, samaya, is primarily a means of regulating individual conduct or activity. Equally it is a means of securing a particular view or level of meditation.

All the schools of Tibetan Buddhism include teachings derived from all the three major stands of Indian Buddhism, the Hinayana, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. Therefore, varying traditions have sought to integrate and present vows or commitments as a unified system for the benefit of the practitioner. Within the Nyingma tradition, the best known and most influential work of this genre is the Ascertainment of the Three Vows, composed by Ngari Panchen Pema Wangyal (mnga’ ris paN chen pad+ma dbang rgyal; 1487-1543) and its commentary by Lochen Dharmashri (lo chen dharma shri; 1654-1717). They are both found in the Nyingma Kama, Volume 51.

Vows of Pratimoksa

Pious attendants (shravaka) who seek to enter the stream to enlightenment and eventually to become arhats are required to observe a number of vows conductive to individual liberation, the pratimoksha, from rebirth in cyclic existence. Such precepts include (1) short-term vows that are taken by laymen and laywomen (for a single day) entailing abstinence from killing, sexual misconduct, stealing, lying, alcohol, frivolous activities, eating after lunch, and using high seats or beds; (2) lifelong vows taken by devout laymen or laywomen which require one not to kill, lie, steal, be intoxicated, or commit sexual misconduct; (3) lifelong vows taken by novice monks or nuns, which include ten rules of training and thirty-three subsidiary restrictive rules; (4) the vows of a probationary nun, which include six basic precepts and six ancillary precepts; (5) the two-hundred and fifty-three vows taken by a fully ordained monk; and (6) the three hundred and sixty four vows maintained by fully ordained nuns.

The majority of these vows concern deportment, dress, sexual abstinence, eating, drinking, walking, sleeping arrangements, and other modes of daily regimen, which are all deemed appropriate for renunciates. There are also the vows of abstinence from the “four defeats:” murder, sexual misconduct, stealing and lying. Some advanced renunciates may additionally practice the so-called twelve ascetic virtues, which entail further restrictions on diet, attire and residence.

Vows of the Bodhisattva

Bodhisattvas are spiritual trainees dedicated to the cultivation and fulfillment of the altruistic intention to attain enlightenment, by gradually traversing the five paths and ten levels. Rather than simply seeking freedom from their own individual suffering, they cultivate four immeasurable aspirations: loving kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity. They vow to remain within cyclic existence in order to remove the sufferings of all sentient beings.

At the same time, they cultivate discriminative awareness through which selflessness and absence of conceptual elaboration are fully realized. To this end, the aspiring bodhisattva will act virtuously in accord with the six perfections. He will control malpractices by avoiding nineteen or twenty root downfalls (and forty-six lesser transgressions). These are described as perpetual vows, which are to be maintained over a succession of lifetimes.

The nineteen root downfalls are enumerated as follows: Five root downfalls are certain for kings, namely, to steal the wealth of the Three Precious Jewels, to punish disciplined monks, to divert a renunciate from his or her training, to commit the five inexpiable crimes, and to hold wrong views. Five are for ministers, namely, to subjugate towns, countryside, citadels, cities, and provinces. Eight are for ordinary persons, namely, to teach emptiness to those of unrefined intelligence, to oppose those who enter the Mahayana, to break monastic vows on the pretext of joining the Mahayana, to support the Hinayana, to praise oneself and deprecate others, to extol one's own patience, to dispense or receive property belonging to the Buddhist community, and to teach the meditation of calm abiding to those who are loud-mouthed.

One root downfall is common to all persons, namely to abandon the altruistic intention to attain enlightenment.

The enumeration of twenty root downfalls additionally includes the act of abandoning the actual implementation of the path to enlightenment.

The forty-six transgressions include thirty-four contradicting the accumulation of virtue and twelve contradicting actions undertaken on behalf of others.

Samaya: the vows of the tantika

Commitments, or samaya, are sacred pledges taken by practitioners of the Vajrayana. They vow to they persevere, through body, speech and mind, to maintain the appropriate levels of renunciation and attainment.

The basic distinction between vows and commitments is that vows depend on individual mental control whereas commitments are secured by maintaining the buddha-body, speech and mind without degeneration. It is said that the correct observance of commitments brings certain benefits when they are guarded, whereas their infringement brings certain retributions.

Each class of tantra has its own categorization of basic and ancillary commitments, which complement the aforementioned vows. Commitments therefore may entail the observation of specific precepts which are common to a whole class of tantra or individual preceptsh must be observed in relation to a particular meditational deity. When such commitments are broken they must be restored through appropriate Vajrayana ritual practices, for their degeneration may cause serious hindrances to progress on the path.

The observance of vows and commitments is intimately connected with the view and meditation upheld at each stage of development. See “Vajrayana Commitments” for a more in-depth description.

Longchen Rabjampa (klong chen rab ’byam pa) writes that the vows of renunciation adopted by pious attendants should be guarded by a practitioner who desires peace and happiness for herself alone, for the duration of her life. The bodhisattva vows bind the mind with moral discipline which has a dual purpose – they cause the practitioner to attain realization and extraordinary enlightened attributes through the accumulation of virtue, and they benefit others by actions undertaken on behalf of sentient beings. The samaya vows bring a great wave of benefit for others and transform dissonant mental states into pristine cognition. He further explains how the monastic vows of renunciation, the bodhisattva vows and the tantric commitments, can all be maintained without contradiction.

Those who have successfully guarded their commitments are said to accomplish all their purposes, provisional and conclusive. Conversely, retribution is exacted when commitments have been violated. On the question of the repairing or restoration of broken commitments, Longchen Rabjampa adds that whereas there are no means of restoring the broken vows of the pious attendants, the tantras do possess the means capable of repairing violations of the commitments. Purification is said to occur through rites of fulfillment and confession, attempting to realign one's ordinary body, speech and mind with the foremost commitments of buddha-body, speech and mind, which have been violated and broken.

II. Modes of Transmissions

According to Nyingma history, the three inner classes of tantra, Mahayoga, Anuyoga and Atiyoga, all derive ultimately from Samantabhadra, the primordial buddha-body of reality. They have been transmitted down to the present day in three distinctive phases: the lineage of the enlightened intention of the conquerors, the lineage of the symbolic gestures of the awareness holders, and the lineage of aural transmission through exalted individuals. Furthermore, there are two modes of transmission that are at work in Tibet: oral transmission, or Kama (bka’ ma) and revelation, or terma (gter ma).

The lineages of the three inner classes of tantra – Mahayoga, Anuyoga and Atiyoga – all derive ultimately from Samantabhadra – the primordial buddha-body of reality, the fundamental nature or actual reality of buddha-mind.

Manifesting in the realm of Great Akanistha, in the form of Vajradhara, endowed with all the signs and marks of buddhahood, Samantabhadra confers through the blessing of his enlightened intention, the realization of manifestly perfect buddhahood upon the five buddhas (Vairocana and so forth) who preside over the assembly of the hundred peaceful and wrathful deities, and who assume the buddha-body of perfect resource, inseparable from himself. This transmission is known as the lineage of the enlightened intention of the conquerors, and is therefore devoid of symbolic gestures or verbal expressions.

Simultaneously, in a special realm of Akanistha, the same blessing is conferred by the peaceful aspects of buddha-body of perfect resource – Vairocana and so forth – through symbolic gestures indicative of enlightened intention, upon the most exalted bodhisattvas – Vajrapani, Avalokiteshvara and Manjughosa, each of whom is responsible for communicating these teachings symbolically to their respective followers – yaksas, nagas and devas.

Meanwhile, in lesser realms of Akanistha the wrathful aspects of the buddha-body of perfect resource confer the same blessing through the imperishable sound of pure vibration upon harmful beings – Rudra, Bhairava and so forth; and, in a lower realm known as the Abode of the Thirty-three Gods (Trayatrimsha), the Buddha Vajrasattva bestowed the pith instructions of the Great Perfection upon his own emanation, Adhicitta, a divine being whose realization was also instantaneously born.

The first human recipient of this lineage is considered to have been the latter’s offspring – Prahevajra of Oddiyana, known in Tibetan as Garab Dorje (dga’ rab rdo rje).

In more conventional and terrestrial realms, such as Mt Malaya, Vajrapani then imparted the tantras symbolically to five exalted being, one of whom, Vimalkirti the Licchavi, was human. These transmissions, whereby the teachings of the buddha-body of perfect resource are conferred on the buddha-body of emanation, are collectively known as the lineages of the symbolic gestures of the awareness-holders, and are therefore devoid of verbal expressions.

The three classes of tantra were thereafter transmitted in the human world through lineages established by exalted individuals, and their respective texts gradually established. Among them, King Indrabhuti who had received the teachings from Vajrapani, and Vajrasattva transmitted the Mahayoga Tantras. His successor Kukkuraja divided them into eighteen books. The eight classes of sadhana based upon them fell to Humkara and so forth.

King Indrabhuti assumed the name Vyakaranavajra and, as such, he received the Anuyoga tantras from the aforementioned Vimalakirti, transmitting them in turn through Kambalapada, Prahevajra, Shakyaprabha (Prabhahasti), Shakyasimha (Padmasambhava), Dharanraksita, and Dharmabodhi.

The Atiyoga tantras are said to have been transmitted by Prahevajra through Manjushrmitra, who divided them into three classes, and Sri Simha who divided the pith instructions into four teaching-cycles. In this transmission the buddha-body of emanation confers the teachings upon human beings by word and letter. It is known as the lineage of the aural transmission through exalted persons. It continues down to the present day through an unbroken succession of oral teachings and spiritual revelations.

With regard to the class of spiritual revelations there are three additional modes of transmission that are considered to be orthodox. Among them, the lineage empowered by enlightened aspiration. This includes those treasure finders who discover their appropriate revelations on the basis of the former enlightened aspirations of Padmasambhava and Yeshe Tsogyal (ye shes mtsho rgyal) that the indicated individuals will emerge in the future to reveal their respective treasures.

The lineage of prophetically declared spiritual succession includes those treasure-finders whose actual names or circumstances have been prophesized in the writings of Padmasambhava. Finally, the lineage of the dakinis’ seal of entrustment includes those treasure-finders to whom the guardians of the treasures rightfully bequeath encoded texts, which they alone are able to interpret.

Kama Transmission

Nyingma Kama (rnying ma bka’ ma) literally means the Oral Lineage of the Ancient Ones. The term Kama in general refers to the Buddhist teachings that came through a long lineage from one master to another. Nyingma Kama specifically is a collection of teachings from the three inner tantras (nang brgyud sde gsum) that are considered to have been brought to Tibet from India and translated into Tibetan during the early translation period (8th and 9th centuries). Every major Nyingma master since the 8th century holds the Kama lineage.

These Kama teachings were transmitted through a long line of masters dating back to the Indian origins of Buddhism through the time when it was first brought to Tibet. It is said to be the very teachings that Padmasambhava and his disciples were actually practicing. Padmasambhava extracted the quintessence of these elaborated practices as a concise corpus of teachings that where then concealed as termas (gter ma), and revealed later for the sake of future generations.

The Kama is comprised of the teachings of the Trilogy of Sutra, Mayajala, and Citta. Within this structure, the Mayajala serves as the basis or tantra, the Sutra is the commentary or agrama (lung), and the Citta is the essential instruction.

The Mayajala teaching belongs to the Mahayoga. It is based on the philosophical view of the intrinsic purity of all appearances, as well as the equality of samsara and nirvana. It employs meditations on the mandalas of the One Hundred Peaceful and Wrathful Deities as explained in the Guhyagarbha Tantra.

The Sutra belongs to Anuyoga. It is based on the tantric scripture, the Samdhisamgraha Sutra, The Gonpa Dupa Do (dgongs pa ’dus pa mdo), which regards the meaning of all the Buddhist vehicles in the context of the view of Anuyoga. It is path has two aspects: the path of means which uses yogic exercises, and the path of liberation.

Citta refers to the instructions of the mind class of the Great Perfection. These teachings are concerned with sustaining the recognition of mind’s undeluded clarity, unstained by the confusion of samsara. This is a most profound path, through which many generations of meditators attained enlightenment. Some, like Vairochana’s octogenarian student, Mipam Gonpo (mi pham mgon po), even dissolved their bodies into light.

It is said of the Kama teachings that they “first fell to Nyak, then to Nub, and finally to Zur.” This means that they first were held and propagated by Nyak Janakumara (gnyags dznya na ku ma ra), next by Nub Sanggye Yeshe (gnubs sangs rgyas ye shes), and finally by the masters of the Zur lineage. Both Nyak Janakumara and Nub Sanggye Yeshe were direct disciples of Padmasambhava and Vimalamitra and are among the Twenty-five Disciples.

The Zur lineage began with Zur Shakya Jungne (zur po che shakya ’byung gnas), Zungchung Sherab Drakpa (zur chung shes rab ’byung gnas), and Zur Shakya Sengge (zur shakya seng ge). This lineage was well-known for its practice of Yangdag Heruka, and also established an important lineage of teaching the Sutra, Mayajala, and Citta Sections.

From these masters onward, the Kama teaching spread widely. The tradition of the Zur clan remained a hub of the Nyingma Kama teachings in Central Tibet. In eastern Tibet the Kama was preserved at the Katog monastery which was established by the great master Dampa Deshek (dam pa bde gshegs) in the 12th century.

Terma Transmission

Since the tenth century, Tibetan Buddhist traditions have recognized the discovery of concealed teachings – terma – as a profound and authentic form of transmission of the teachings. This mode of transmission is considered the “short” mode, as opposed to the “long” mode of the Kama, which has been transmitted person to person since the 8th century. Terma, in contrast, claims to be a direct transmission from Padmasambhava (or, less frequently, Vairocana or another 8th century master) and the treasure discover, bypassing the centuries inbetween.

The treasures are said to have been concealed by Padmasambhava to be discovered in the appropriate time. They are considered to be the condensed quintessence of the Kama, which contains the main teachings practiced at the time of Padmasambhava and upon which the termas are based.

According to the foundational legend, when Padmasambhava bestowed the ripening empowerments and liberating instructions upon the king Trisong Detsen (khri srong lde’u btsan), Yeshe Tsogyal and other of his twenty-five main disciples, he entrusted many teachings to each of them for later dissemination. With their assistance he then concealed these as treasures in various places – rocks, lake, temples, statues, and even in the sky and in the mindstream of the recipient. He then prophesied that, in the future, these disciples would reincarnate, reveal these teachings from their place of concealment and spread them for the sake of beings.

Those who reveal treasure are called tertons (gter ston). In due time, a terton is said to experience visions or signs indicating how and where to discover his or her destined terma. Often they experience a vision of a being who hands them an inventory of the treasures to be revealed, with the location.

A kind of treasure that is sometimes considered a third stream of transmission is dagnang (dag snang) or pure vision. As explained by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, in pure visions the terton has a vision of Padmasambhava or another saint from the lineage who transmits the teaching. Two other primary methods of revelation, to be discussed below, are earth treasure (sa gter), which are physical objects revealed from actual places, and mind treasure (dgongs gter), which are extracted from the mind of the treasure revealer.

The terma teachings are considered powerful because they were not corrupted by the impurities that inevitably occurred in the history of lineages and are particularly relevant for the time of their prophesized discovery. That is, as direct transmissions from Padmasambhava or other Imperial-era saints, they did not suffer from scribal errors or innovations introduced by lineage holders over the centuries.

There are customarily three ways by which Padmasambhava set forth a teaching as a treasure:

1) By giving a prediction: Padmasambhava predicted that the benefit of these teachings for sentient beings will be accomplished by a certain disciple and that the terma will be revealed at a certain appropriate time, place, and circumstance.

2) By means of an empowerment through wishing prayers: While focusing his wisdom mind, Padmasambhava prayed that the teachings and pith instructions given at the time of bestowing the empowerment may fully and clearly arise in the mind of the disciple in the rebirth during which he or she is meant to reveal the treasure. The disciples also prayed in the same way. This is why almost all Nyingma termas were revealed by incarnations of directs disciples of Padmasambhava, the main ones being known as the “Twenty-five, The Lord and Subjects” or jebang nyernga (rje ’bangs nyer lnga).

3) By entrusting the dakinis to look after the terma: Padmasambhava put the dakinis in charge of ensuring that, in due time, the terton will find the treasure, will be able to transmit it to suitable disciples, and that his lineage will carry great blessings while being kept secret from unqualified disciples.

The terma teaching is said to have then been placed under the guardianship of a specific protector, referred to as a Terma Protector (gter srung), who will only allow the right person to be given access to the treasure. One some occasions, however, a terton may bless another realized master to extract the treasure in his place. This is how, for instance, Jedrung Trinle Jampa Jungne (rje drung phrin las byams pa ’byung gnas) of Riwoche (ri bo ches) asked the famed yogi Gara Lama (mgar ra bla ma), in front of a large crowd, to retrieve a terma on Amitayus, the Buddha of Infinite Life.

Out of these three aspects of the transmission, the wishing prayer of Padmasambhava is considered to be the most important, as it is the means by which the entire process unfolds. In fact, it is sometimes said that whichever form the terma is found, such as dakini symbolic scripts written on a yellow parchment (shog ser), this is said to be a mere support for remembering the time when the terton received the teachings from Padmasambhava. The real transmission is said to have been given from mind to mind given by Padmasambhava.

On the basis of this symbolic support, the terton with proper karma will thus be able to “establish” (brtan la ’bab) the whole teachings, sometimes in the flash of an instant, and put it in writing without any of the hesitations and discursive thinking that normally characterize ordinary literary compositions. It is said that the terton may see the whole text “as if looking into a mirror.” It is explained that the sight of the dakini scripts acts as a trigger so that the teachings arise effortlessly from the creative power of the vast expanse of pure awareness.

Some termas arise in ways that are clearly and beautifully written, complete and in perfect order, such as the Prayer in Seven Chapters revealed by Rigdzin Godemchen (rig ’dzin rgod ldem chen), some in a seemingly disordered and obscure style that requires it to be rearranged and clarified, for instance some of the termas revealed by Rigdzin Longsel Nyingpo (rig ’dzin klong gsal snying po). This is why, in addition to the root terma, a great master in the terton’s lineage usually needs to prepare a text which incorporates the terma teachings but is arranged in the form of a “means of accomplishment” or sadhana, or a ritual text that can readily be used by practitioners.

How Terma is Found

Over its more than one thousand year history the treasure tradition has standardized the narrative of treasure discovery. Although few histories of revelations follow the standards narrative, it is useful to survey in order to understand the many steps that the tradition claims as part of the treasure discovery process.

The first thing that is said to be found by the terton is the list or inventory (dkar chag or byang bu) of the treasures that he is meant to reveal during his life. This list is found, like other termas, in rocks, statues, and so on, or is given to the terton in a vision or in reality by Padmasambhava. He appears sometimes in the guise of a yogi, a monk or in any other form. It can also be given by one of the guardians of the teachings. Ratna Lingpa (rat+na gling pa) is said to be the only terton who found all the termas predicted in his inventory. This is why his teachings are said to carry particular blessings and efficacy.

In order for the terton to find the treasures listed in the inventory, many auspicious connections need to be gathered. Often one condition is that the terton meet a predestined spiritual consort through whom his or her spiritual channels will be untied, allowing the free flowing of the teachings through the terton’s wisdom mind. That is, the treasure tradition maintains that sexual yoga is necessary for the discovery of treasure, a claim that has earned the tradition considerable scorn by its (primarily ordained) detractors. This applies to both male and female tertons. There were, however, a few major tertons, such as Rigdzin Jatson Nyingpo (rig ’dzin ’ja’ tshon snying po) and Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (’jam dbyangs mkhyen brtse’i dbang po) who were celibate and did not rely upon a spiritual consort to reveal their termas. However, Khyentse Wangpo bemoaned the fact that his treasures were only mind treasures and not earth treasures, which he considered superior.

Termas are said to be extracted from their place of concealment at the time when they are most needed and beneficial to sentient beings. Depending upon the circumstances, the quality of the auspicious connections, the purity of sacred bounds between teacher and disciple (samaya) and the merit of beings, the terma will be revealed more or less easily and will benefit a greater or a smaller number of people. When Dudjom Rinpoche (bdud ’joms rin po che), for example, was sitting in small room facing the entrance of Padmasambhava’s cave on the cliff of Paro Taksang (pa ro stag tshang) in Bhutan, the yellow scroll for his Vajrakilaya cycle of teachings came floating in the air through a small open window and landed in his lap. In some other cases, tertons are said to have toiled for days with axes and rods to reach the terma deeply embedded in the rock.

Normally, only the terton who was meant to find the terma is able to decipher the dakini script. Yet, according to Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, other tertons may get a general idea of the kind of treasure the scripts code is for, such as a guru sadhana or a Dzogchen teaching. Some exceptional tertons like Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo are said to be able to understand all forms of dakini scripts. Khyentse Wangpo once confided that, on one occasion, he had been able to see clearly the locations of all the termas hidden in Tibet and other places.

Such great tertons are also the ultimate reference to judge the authenticity of other termas. It is therefore customary for a terton to present his terma to such a master and ask him to confirm whether his discovery is genuine and will benefit beings, or whether it should be discarded. Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche used to show his mind treasures to his teacher, Dzongsar Khyentse Chokyi Lodro (rdzong sar mkhyen brtse chos kyi blo gros). Chokyi Lodro not only validated the termas but requested Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche to give him the transmission for them. Often treasure revealers are taken under the sponsorship of ordained lamas, granting them the legitimacy that celibate institutional hierarchs wield in Tibetan society.

The tradition allows for two or more tertons being entrusted with the same treasure discovering it either together or simultaneously in various places. This was often the case with the three great 19th century masters Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, Jamgon Kongtrul and Choggyur Lingpa (mchog gyur gling pa). Once, Choggyur Lingpa came to show Khyentse Wangpo the treasure of the Sampa Lhundrup cycle (bsam pa lhun grub) that he had just revealed. Khyentse Wangpo not only confirmed the authenticity of the terma, but added that he had exactly the same treasure, almost word for word, and that there was not need for him to put him into writing, since Choggyur Lingpa had already done so. A similar process happened for Choggyur Lingpa’s Barche Kunsel (bar chad kun gsal) treasure; Khyentse Wangpo claimed to have also revealed it, but as mind treasure, whereas Choggyur Lingpa’s was earth treasure.

Having received the treasure inventory, the terton next follows it to the proper location where he needs to find and “open the door of the treasure” that often bears a distinctive mark. In there he usually finds a treasure box (gter sgrom) that often takes the aspect of a round brown jewel stone that contains the yellow scroll. He then has to put back something in place of the treasure (gter tshab) and again seal the place of concealment. This is done to placate the non-human entity who guards the treasure, a form of barter to prevent the guardian from feeling bereft. The act of revelation is either done alone or with assistance, and is sometimes performed before an audience of devotees in an event called a “public treasure” (khrom gter). The fifteenth century terton Pema Lingpa (pad+ma gling pa) was particularly famous of public treasures, and Choggyur Lingpa made a habit of the practice in the later part of his career.

As mentioned above, auspicious circumstances play a vital role in the revelation of termas. The story is told that once Padmasambhava appeared in person in front of Ratna Lingpa in the form of a yogi dressed in yellow raw silk. He showed him three scrolls, a white, a red and a blue one, and asked Ratna Lingpa to choose one of them. Ratna Lingpa answered that he wanted all three. Because of the auspicious connection created by his answer, Ratna Lingpa received all three inventories and revealed in a single life time the termas he would have otherwise revealed in three successive life times.

Seemingly insignificant events may also create various levels of auspicious links. Once, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche was requested at Neten Monastery (gnas bstan) in Nangchen to decipher a yellow scroll rediscovered by Choggyur Lingpa, which the latter had never put into writing. Khyentse Rinpoche put the scroll in a cup filled with sacred amrita substances and asked the monks to perform an elaborate ganachakra offering. At some point during the ceremony, he requested ink and paper and was brought about fifty white sheets, which he soon filled with his writings. When he handed the text over to the lama who had made the request he said: “There was three versions of the terma, a long elaborate one, a medium one and a condensed one. According to the amount of paper you gave me, I have put into writing the medium-sized one.” Thus, some tertons write out a terma briefly while some in its full length. An example of a complete length terma is the thirteen-volume terma of Sanggye Lingpa (sangs rgyas gling pa, the Lama Gongdu (bla ma dgongs ’dus).

In many cases, the terton keeps his discovery secret for many years, and practices the teachings they contain until achieving signs of accomplishment. He will then transmit it to a single disciple. Such first recipient of the teachings, who has generally been prophesized in the terma itself, becomes the holder of the teaching. Jatshon Nyingpo kept his Konchok Chidu Treasure (dkon mchog

Background Information

BUDDHISM IN TIBET

The Jonang Tradition of Tibetan Buddhism

GELUG TRADITION

The Gelug Tradition

The Gelugpa Monastic Curriculum

KADAM TRADITION

The Kadampa Tradition

KAGYU TRADITION

The Kagyu Tradition of Tibetan Buddhism

NYINGMA TRADITION

The Teachings of the Nyingma Tradition

Nyingma History of the Early Propagation of Buddhism to Tibet