Difference between revisions of "Ancient Japan"

(Created page with "thumb|250px|thumb|250px|thumb|250px|thumb|250px|thumb|250px| <poem...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:124 MG 9812.jpg|thumb|250px|]][[File:10f5m2.jpg|thumb|250px|]][[File:100000174.jpg|thumb|250px|]][[File:2 ha10.jpg|thumb|250px|]][[File:565 rge.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:124 MG 9812.jpg|thumb|250px|]][[File:10f5m2.jpg|thumb|250px|]][[File:100000174.jpg|thumb|250px|]][[File:2 ha10.jpg|thumb|250px|]][[File:565 rge.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | {{Wiki|Archaeologists}} are still working to discover the very early origins of [[human]] {{Wiki|culture}} in [[Japan]]. There is definite {{Wiki|evidence}} of [[humans]] at least 30,000 years ago, but little [[information]] about these [[people]] has survived. Probably about 10,000 b.c. [[people]] whom we now call the | + | {{Wiki|Archaeologists}} are still working to discover the very early origins of [[human]] {{Wiki|culture}} in [[Japan]]. There is definite {{Wiki|evidence}} of [[humans]] at least 30,000 years ago, but little [[information]] about these [[people]] has survived. Probably about 10,000 b.c. [[people]] whom we now call the Jomon were living in [[Japan]]. The [[name]] Jomon (“ropepattern”) comes from a type of pottery they made. It looks as if rope was pressed onto it to make markings, or it was made by coiling strips of clay. By the fourth century b.c., a new {{Wiki|culture}} emerged in [[Japan]]. These people—named Yayoi, after the place where their homes were first found by archaeologists—grew {{Wiki|rice}} and used {{Wiki|copper}} and other metals that earlier inhabitants did not. The gap between 10,000 b.c. and 300 b.c. is vast, and there is considerable [[debate]] among [[scholars]] about what happened during that [[time]]. |

They are not even sure where the Yayoi came from, though they can offer a good guess. Because of the metal [[objects]] and items such as mirrors associated with Yayoi excavations, {{Wiki|archaeologists}} believe that the Yayoi came from [[China]] and [[Korea]], or traded with [[people]] who did. The exact [[nature]] of this immigration or trade is still being studied, as is the {{Wiki|culture}} of the times. But the Yayoi [[people]] used sophisticated {{Wiki|iron}} tools and had {{Wiki|social}} and agricultural systems capable of sustaining large populations. Large populations almost always have complex [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} systems, and this seems to fit with {{Wiki|ancient}} [[Japan]] as well. | They are not even sure where the Yayoi came from, though they can offer a good guess. Because of the metal [[objects]] and items such as mirrors associated with Yayoi excavations, {{Wiki|archaeologists}} believe that the Yayoi came from [[China]] and [[Korea]], or traded with [[people]] who did. The exact [[nature]] of this immigration or trade is still being studied, as is the {{Wiki|culture}} of the times. But the Yayoi [[people]] used sophisticated {{Wiki|iron}} tools and had {{Wiki|social}} and agricultural systems capable of sustaining large populations. Large populations almost always have complex [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} systems, and this seems to fit with {{Wiki|ancient}} [[Japan]] as well. | ||

| − | The Yayoi seem to have spread from areas in {{Wiki|western}} [[Japan]] eastward. By a.d. 250–350, the inhabitants of the Nara plain in [[Japan]] built large burial mounds, called kofun in [[Japanese]]. {{Wiki|Historians}} generally connect the growth and spread of these keyhole-shaped tombs with the spread of the Yamato {{Wiki|clan}}, a large extended family that was prominent in the Yamat region of | + | The Yayoi seem to have spread from areas in {{Wiki|western}} [[Japan]] eastward. By a.d. 250–350, the inhabitants of the Nara plain in [[Japan]] built large burial mounds, called kofun in [[Japanese]]. {{Wiki|Historians}} generally connect the growth and spread of these keyhole-shaped tombs with the spread of the Yamato {{Wiki|clan}}, a large extended family that was prominent in the Yamat region of Kyoshi, the main island of [[Japan]], by the early centuries of the first millennium and controlled {{Wiki|western}} and central [[Japan]]. |

{{Wiki|Archaeologists}} also point out that the kofun are similar to mounds in southern [[Korea]]. There are several possible [[reasons]] for this. One is increased trade between the two areas. Another is the conquest of [[Korea]] by the [[Japanese]] [[people]]. But many anthropologists outside of [[Japan]] accept what is known as the [[horse]] rider {{Wiki|theory}}, which was suggested by Egami Namio. According to this {{Wiki|theory}}, invaders originally from [[China]] settled in [[Korea]] and then came to [[Japan]]. These [[people]]— who rode horses—subdued the early Yamato leaders and substituted themselves as the new rulers. Gradually they took over all of [[Japan]], unifying the many small settlements. | {{Wiki|Archaeologists}} also point out that the kofun are similar to mounds in southern [[Korea]]. There are several possible [[reasons]] for this. One is increased trade between the two areas. Another is the conquest of [[Korea]] by the [[Japanese]] [[people]]. But many anthropologists outside of [[Japan]] accept what is known as the [[horse]] rider {{Wiki|theory}}, which was suggested by Egami Namio. According to this {{Wiki|theory}}, invaders originally from [[China]] settled in [[Korea]] and then came to [[Japan]]. These [[people]]— who rode horses—subdued the early Yamato leaders and substituted themselves as the new rulers. Gradually they took over all of [[Japan]], unifying the many small settlements. | ||

Latest revision as of 18:50, 16 December 2013

Archaeologists are still working to discover the very early origins of human culture in Japan. There is definite evidence of humans at least 30,000 years ago, but little information about these people has survived. Probably about 10,000 b.c. people whom we now call the Jomon were living in Japan. The name Jomon (“ropepattern”) comes from a type of pottery they made. It looks as if rope was pressed onto it to make markings, or it was made by coiling strips of clay. By the fourth century b.c., a new culture emerged in Japan. These people—named Yayoi, after the place where their homes were first found by archaeologists—grew rice and used copper and other metals that earlier inhabitants did not. The gap between 10,000 b.c. and 300 b.c. is vast, and there is considerable debate among scholars about what happened during that time.

They are not even sure where the Yayoi came from, though they can offer a good guess. Because of the metal objects and items such as mirrors associated with Yayoi excavations, archaeologists believe that the Yayoi came from China and Korea, or traded with people who did. The exact nature of this immigration or trade is still being studied, as is the culture of the times. But the Yayoi people used sophisticated iron tools and had social and agricultural systems capable of sustaining large populations. Large populations almost always have complex religious and political systems, and this seems to fit with ancient Japan as well.

The Yayoi seem to have spread from areas in western Japan eastward. By a.d. 250–350, the inhabitants of the Nara plain in Japan built large burial mounds, called kofun in Japanese. Historians generally connect the growth and spread of these keyhole-shaped tombs with the spread of the Yamato clan, a large extended family that was prominent in the Yamat region of Kyoshi, the main island of Japan, by the early centuries of the first millennium and controlled western and central Japan.

Archaeologists also point out that the kofun are similar to mounds in southern Korea. There are several possible reasons for this. One is increased trade between the two areas. Another is the conquest of Korea by the Japanese people. But many anthropologists outside of Japan accept what is known as the horse rider theory, which was suggested by Egami Namio. According to this theory, invaders originally from China settled in Korea and then came to Japan. These people— who rode horses—subdued the early Yamato leaders and substituted themselves as the new rulers. Gradually they took over all of Japan, unifying the many small settlements.

Besides archaeological finds, there is support for this theory in early Japanese myths and legends. Horses, for example, begin to appear only in stories known from a certain time. There are parallels or similarities in some of the myths to events known or thought to have happened. Of course, by their very nature, myths are open to interpretation. It would be extremely misleading to base any historical conclusion on myths alone.

Wherever they came from, the Yamato kings or emperors gradually and steadily extended their rule over the Japanese islands through warfare and diplomacy. Rival states in the Japanese islands were generally organized according to clans or family structures. They were called uji, and an important function of each clan was to honor or venerate ancestral gods.

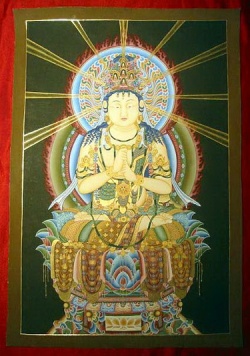

The religion of Japan’s emperor and people is Shinto. It involves the worship of different kami, which can be the spirits of ancestors or the divine essence of natural elements and phenomena, such as the rain or a mountain. To justify their control, the Yamato rulers associated their clan with a story about the beginning of the world that linked them to the gods who had created it. This creation myth, or story about the creation of the world, became central to the Shinto religion. Once writing was introduced in Japan, those oral traditions were recorded in the Kojiki (Book of Ancient Things) and the Nihongi (Chronicles of Japan, compiled in the eighth century).

The Introduction of Buddhism

The country unified under the Yamato clan was strong enough to invade Korea, but the major Asian power at the time was China. By the fifth century a.d. frequent contact between Japan and China brought many Chinese influences to Japan. This helped spread and introduce Buddhism, an important religion that had begun in India centuries before (see Indian influence). Other Chinese belief systems, such as Daoism and Confucianism (see Confucius), were also introduced to Japan. At the same time, Japan’s government began to model itself along the Chinese model. It became more centralized and bureaucratic.

Medieval Japan

Over a period of several hundred years, beginning in the ninth century, the emperor’s power was whittled away. First, powerful families or clans took over as regents, acting as assistants to the emperor and then concentrating their own power. Then, as the central government became weaker, rival families or groups began to assume more authority.

Conflicts between the emperor and powerful families led to a bloody civil war between the Minamoto and Taira clans at the end of the 12th century, culminating in a battle at Dannoura in 1185 that resulted in the annihilation of the Taira, also known as Heike.

This period and especially these battles gave rise to many legends and popular stories in Japan.

In the era that followed, the Shogun, or military leader of Japan, dominated the country, ruling as much in his own name as the emperor’s. Although the emperor and his family lost temporal power, his direct connection to the most important gods in the Japanese Shinto pantheon meant that he retained an important role in society. Others could usurp his authority or rule in his name, but they could not replace him. Nor could they take his place in religious ceremonies.

This unique position helped ensure that the imperial family survived the tumultuous times. But it helped the society as well, giving it continuity and meaning. Japanese traditions— many deeply connected to myth—also survived with the imperial family. The period from 1185 to 1868 was dominated by three different shogunates, or military regimes, periods when different families or clans dominated Japan: the Kamakura Shogunate (1185–1333), the Ashikaga Shogunate (1338–1598), and the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603–1867). The years between the shogunates were times

of great disruption, confusion, and civil war.

In a feudal society, very specific roles are defined and passed on from birth. At the top of the Japanese feudal order was the emperor, followed closely by the

Shogun, the greatest warlord in the country. Beneath him were the daimyo, lords who had great wealth and controlled large domains. Lesser lords rounded out the feudal aristocracy. Beneath them were samurai, warriors who for the most part were not noble and did not own land (though there were a few notable exceptions). The samurai are greatly celebrated in legends for their fighting ability, but during the later feudal period many worked as administrators and bureaucrats— performing what today we might call “desk jobs.”

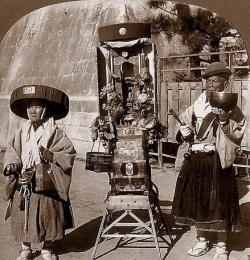

The most numerous class by far were farmers, ranked locally generally according to their wealth. Merchants and artisans were officially at the bottom of the local hierarchy, but in fact enjoyed a much higher standard of luxury than farmers and day laborers. Villages usually had a local government, with many decisions being made by village elders and headmen, who would deal with the local daimyo’s representatives.

The West

Europe played no role in Japanese culture until the arrival of Portuguese and other traders in the 16th century. After a brief period during which missionaries brought Christianity to the islands, trade and contact with the West was severely limited. Relations were not established with major Western countries until the United States threatened Japan with force in 1854.

Japan’s role in Asia gradually increased in the late 19th and 20th centuries. It fought a war with Russia in 1904–1905 and took a small part in World War I. In the 1930s it became aggressively imperialistic, invading China and other countries. Eventually it went to war with the United States and the Allies in World War II. After the war, the Japanese government was reorganized under U.S. occupation.

This ended the emperor’s direct role in government, though he remains an important ceremonial figure in Japan today.

Japanese myths developed and changed as the country did. As we look at this evolution, it is important to remember that it was very complex. Examining the surviving myths is akin to looking at a series of snapshots rather than a long, consistent narrative movie.