Difference between revisions of "The Mahasiddha Tradition in Tibet by John Myrdhin Reynolds"

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

:This [[Buddhist]] [[monastic]] {{Wiki|culture}} was introduced into [[Tibet]] from [[India]] in the seventh and eighth centuries of our {{Wiki|era}}, and revived again in the eleventh century after a {{Wiki|temporary}} eclipse. The [[Indian]] [[Buddhist]] [[scholars]] brought with them to [[Tibet]] and exceptionally rich and profound thousand year old [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|culture}}, and whereas this {{Wiki|culture}} largely disappeared from [[India]] itself in the thirteenth century due to the total destruction of the great [[Buddhist]] [[monastic]] {{Wiki|universities}} of {{Wiki|Northern India}} by rampaging invading hordes from {{Wiki|Afghanistan}} and {{Wiki|Central Asia}} bent on pillage, loot, rape, and the forcible [[conversion]] of conquered native populations to the ascendant [[religion]] of {{Wiki|Islam}}, much of the [[intellectual]] heritage of these {{Wiki|universities}}, lost in [[India]], was preserved in [[Tibet]]. | :This [[Buddhist]] [[monastic]] {{Wiki|culture}} was introduced into [[Tibet]] from [[India]] in the seventh and eighth centuries of our {{Wiki|era}}, and revived again in the eleventh century after a {{Wiki|temporary}} eclipse. The [[Indian]] [[Buddhist]] [[scholars]] brought with them to [[Tibet]] and exceptionally rich and profound thousand year old [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|culture}}, and whereas this {{Wiki|culture}} largely disappeared from [[India]] itself in the thirteenth century due to the total destruction of the great [[Buddhist]] [[monastic]] {{Wiki|universities}} of {{Wiki|Northern India}} by rampaging invading hordes from {{Wiki|Afghanistan}} and {{Wiki|Central Asia}} bent on pillage, loot, rape, and the forcible [[conversion]] of conquered native populations to the ascendant [[religion]] of {{Wiki|Islam}}, much of the [[intellectual]] heritage of these {{Wiki|universities}}, lost in [[India]], was preserved in [[Tibet]]. | ||

| − | :During these early centuries the [[Tibetan]] government sponsored one of the greatest translations projects ever undertaken in history-- translating the bulk of texts of [[Mahayana Buddhism]] from the [[Sanskrit]] [[language]] into [[Tibetan]]. But although this [[monastic]] {{Wiki|culture}} of [[monks]] and [[monasteries]] has been throughout the past 2500 years the principal {{Wiki|social}} institution for the preservation and the [[transmission]] of the [[Buddhist]] heritage, that there have existed other [[forms]] of [[Buddhist teaching]] and practice. | + | :During these early centuries the [[Tibetan]] government sponsored one of the greatest translations projects ever undertaken in history-- translating the bulk of texts of [[Mahayana Buddhism]] from the [[Sanskrit]] [[language]] into [[Tibetan]]. But although this [[monastic]] {{Wiki|culture}} of [[monks]] and [[monasteries]] has been throughout the {{Wiki|past}} 2500 years the [[principal]] {{Wiki|social}} institution for the preservation and the [[transmission]] of the [[Buddhist]] heritage, that there have existed other [[forms]] of [[Buddhist teaching]] and practice. |

: | : | ||

:Even in the [[time]] of [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] himself, not all of his [[principle]] followers were [[monks]]. One example is the [[layman]] and {{Wiki|merchant}} [[Vimalakirti]] who could defeat in [[debate]] on the [[subject]] of [[Shunyata]] or [[emptiness]] the great [[monk]] [[scholar]] [[Shariputra]] himself. [[Scholars]] such as E. Lamotte and E. Conze have speculated that the tension between the {{Wiki|saffron}} robbed [[Elders]] of the [[monastic community]] and the white garbed leaders of the [[Buddhist]] lay {{Wiki|community}}, was one factor in the historical development of the [[Mahayana]]. | :Even in the [[time]] of [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] himself, not all of his [[principle]] followers were [[monks]]. One example is the [[layman]] and {{Wiki|merchant}} [[Vimalakirti]] who could defeat in [[debate]] on the [[subject]] of [[Shunyata]] or [[emptiness]] the great [[monk]] [[scholar]] [[Shariputra]] himself. [[Scholars]] such as E. Lamotte and E. Conze have speculated that the tension between the {{Wiki|saffron}} robbed [[Elders]] of the [[monastic community]] and the white garbed leaders of the [[Buddhist]] lay {{Wiki|community}}, was one factor in the historical development of the [[Mahayana]]. | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Only a century after the passing away of the [[Lord]] [[Buddha]], at or around the council at [[Vaishali]] there was a {{Wiki|schism}} between the [[Sthaviras]] or [[Elders]] and the [[Mahasanghikas]] or {{Wiki|adherents}} of the Greater Assembly, which included many leaders who were not [[monks]]. Whereas the [[traditions]] preserved among the [[Sthaviras]] or elder [[monks]] evolved into the eighteen schools of [[Hinayana Buddhism]], which asserted that in order to attain [[liberation]] from the cycle of [[rebirth]] one must first be [[reborn]] as a {{Wiki|male}} and second become a [[monk]], the [[Mahasanghikas]] held the [[enlightenment]] was open to everyone, {{Wiki|male}} or {{Wiki|female}}, [[monk]] or lay-person, because each {{Wiki|individual}} possessed an inner disposition to [[enlightenment]]. | Only a century after the passing away of the [[Lord]] [[Buddha]], at or around the council at [[Vaishali]] there was a {{Wiki|schism}} between the [[Sthaviras]] or [[Elders]] and the [[Mahasanghikas]] or {{Wiki|adherents}} of the Greater Assembly, which included many leaders who were not [[monks]]. Whereas the [[traditions]] preserved among the [[Sthaviras]] or elder [[monks]] evolved into the eighteen schools of [[Hinayana Buddhism]], which asserted that in order to attain [[liberation]] from the cycle of [[rebirth]] one must first be [[reborn]] as a {{Wiki|male}} and second become a [[monk]], the [[Mahasanghikas]] held the [[enlightenment]] was open to everyone, {{Wiki|male}} or {{Wiki|female}}, [[monk]] or lay-person, because each {{Wiki|individual}} possessed an inner disposition to [[enlightenment]]. | ||

| − | This {{Wiki|community}} of the [[Mahasanghikas]] was the {{Wiki|matrix}} out of which the later [[Mahayana]] grew-- but both [[Sthaviras]] and [[Mahasanghikas]] possessed [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] [[traditions]] that went back to the [[historical Buddha]] himself, although their emphases differed. In the Mahasanghika-Mahayana [[tradition]] it was possible for the [[layman]] or the laywoman to be a full-fledged [[practitioner]] of the [[Buddha Dharma]], and not just a second rate citizen of the [[Sangha]] in [[relation]] to the [[ordained]] {{Wiki|clergy}} of the [[monks]]. | + | This {{Wiki|community}} of the [[Mahasanghikas]] was the {{Wiki|matrix}} out of which the later [[Mahayana]] grew-- but both [[Sthaviras]] and [[Mahasanghikas]] possessed [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] [[traditions]] that went back to the [[historical Buddha]] himself, although their emphases differed. In the [[Mahasanghika-Mahayana]] [[tradition]] it was possible for the [[layman]] or the laywoman to be a full-fledged [[practitioner]] of the [[Buddha Dharma]], and not just a second rate citizen of the [[Sangha]] in [[relation]] to the [[ordained]] {{Wiki|clergy}} of the [[monks]]. |

: | : | ||

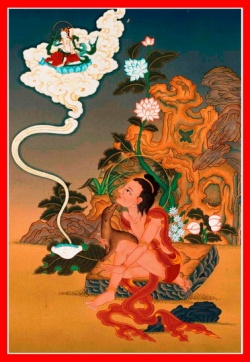

:But most important historically for the development of [[Buddhism]] in [[Tibet]] was the [[Mahasiddha]] [[Tradition]] that evolved in [[North]] [[India]] in the early {{Wiki|Medieval}} Period (3-13 cen. CE). {{Wiki|Philosophically}} this {{Wiki|movement}} was based on the [[insights]] revealed in the [[Mahayana Sutras]] and as systematized in the [[Madhyamaka]] and [[Chittamatrin]] schools of [[philosophy]], but the methods of [[meditation]] and practice were radically different than anything seen in the [[monasteries]]. The [[Sanskrit]] term [[Mahasiddha]] means a great {{Wiki|adept}}. | :But most important historically for the development of [[Buddhism]] in [[Tibet]] was the [[Mahasiddha]] [[Tradition]] that evolved in [[North]] [[India]] in the early {{Wiki|Medieval}} Period (3-13 cen. CE). {{Wiki|Philosophically}} this {{Wiki|movement}} was based on the [[insights]] revealed in the [[Mahayana Sutras]] and as systematized in the [[Madhyamaka]] and [[Chittamatrin]] schools of [[philosophy]], but the methods of [[meditation]] and practice were radically different than anything seen in the [[monasteries]]. The [[Sanskrit]] term [[Mahasiddha]] means a great {{Wiki|adept}}. | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

[[File:84mahasiddha-03.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:84mahasiddha-03.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | :The [[form]] of ascesis expounded in the [[Tantras]], unlike the [[Sutras]] and the [[Vinaya]] which taught the methods of the [[path]] of [[renunciation]], taught the methods of [[transformation]], where the [[poisons]] of the [[passions]], far from being renounced were actually cultivated to their extreme, in order that their [[energy]] might be transmuted within the [[alchemical]] vessel of the [[physical]] [[human]] [[body]] into the luminous [[nectar]] of [[enlightened]] [[awareness]]. There was a deliberate and clear parallel here with [[alchemy]]-- the [[kleshas]] or [[passions]] through the [[alchemical]] process of [[sadhana]] were transmuted into [[Jnana]] ([[gnosis]]) or [[knowledge]]. Thus the things of the [[world]] that are usually renounced by the [[ascetic]]-- wine, meat, and {{Wiki|sex}}-- which are seen as the [[fetters]] binding the [[spirit]] to [[matter]] and [[nature]], especially the latter (women and {{Wiki|sex}}) are not renounced in the higher [[Tantras]] but actually employed as the very means to [[enlightenment]]. But this was not an excuse or rationale to party with wine, women, and song-- it represented a highly [[disciplined]] [[ascetic]] [[path]]. And since the methods of the [[Tantra]] principally works with [[energy]], and one of the most important and powerful energies in [[human]] [[experience]] is {{Wiki|sex}} [[desire]], a sophisticated {{Wiki|sexual}} [[yoga]] developed, known as Upayamarga and as Karmamudra. | + | :The [[form]] of ascesis expounded in the [[Tantras]], unlike the [[Sutras]] and the [[Vinaya]] which taught the methods of the [[path]] of [[renunciation]], taught the methods of [[transformation]], where the [[poisons]] of the [[passions]], far from being renounced were actually cultivated to their extreme, in order that their [[energy]] might be transmuted within the [[alchemical]] vessel of the [[physical]] [[human]] [[body]] into the luminous [[nectar]] of [[enlightened]] [[awareness]]. There was a deliberate and clear parallel here with [[alchemy]]-- the [[kleshas]] or [[passions]] through the [[alchemical]] process of [[sadhana]] were transmuted into [[Jnana]] ([[gnosis]]) or [[knowledge]]. Thus the things of the [[world]] that are usually renounced by the [[ascetic]]-- wine, meat, and {{Wiki|sex}}-- which are seen as the [[fetters]] binding the [[spirit]] to [[matter]] and [[nature]], especially the latter (women and {{Wiki|sex}}) are not renounced in the higher [[Tantras]] but actually employed as the very means to [[enlightenment]]. But this was not an excuse or rationale to party with wine, women, and song-- it represented a highly [[disciplined]] [[ascetic]] [[path]]. And since the methods of the [[Tantra]] principally works with [[energy]], and one of the most important and powerful energies in [[human]] [[experience]] is {{Wiki|sex}} [[desire]], a sophisticated {{Wiki|sexual}} [[yoga]] developed, known as [[Upayamarga]] and as [[Karmamudra]]. |

| − | [[Yoga]] practitioners took [[consorts]] or {{Wiki|sexual}} partners from among the village girls, including even outcaste girls, such as Dombhis, Chandalis, etc. and lived with them in [[retreat]] or in the villages while plying humbles trades. For example, the young [[Brahman]] [[scholar]] [[Saraha]] {{Wiki|defiled}} his [[caste]] {{Wiki|status}} by living openly with a low [[caste]] who was an arrow-maker, yet he is considered one of the greatest poets and [[scholars]] of the [[Buddhist]] [[Tantric]] [[tradition]]. Or [[Naropa]], once a {{Wiki|professor}} and chancellor at [[Nalanda]] [[monastic]] {{Wiki|university}}, abandoned his {{Wiki|academic}} career to pursue the teachings of [[Tilopa]], a wild-eyed and apparently half-mad [[ascetic]] who lived in a series of remote [[cremation]] grounds in the company of women of questionable [[virtue]]. In [[India]] generally the [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]] were not practiced in the [[monasteries]] because their practice was incompatible with the [[Vinaya]], the rules and [[vows]] incumbent upon a [[monk]]. | + | [[Yoga]] practitioners took [[consorts]] or {{Wiki|sexual}} partners from among the village girls, including even outcaste girls, such as [[Dombhis]], [[Chandalis]], etc. and lived with them in [[retreat]] or in the villages while plying humbles trades. For example, the young [[Brahman]] [[scholar]] [[Saraha]] {{Wiki|defiled}} his [[caste]] {{Wiki|status}} by living openly with a low [[caste]] who was an arrow-maker, yet he is considered one of the greatest poets and [[scholars]] of the [[Buddhist]] [[Tantric]] [[tradition]]. Or [[Naropa]], once a {{Wiki|professor}} and chancellor at [[Nalanda]] [[monastic]] {{Wiki|university}}, abandoned his {{Wiki|academic}} career to pursue the teachings of [[Tilopa]], a wild-eyed and apparently half-mad [[ascetic]] who lived in a series of remote [[cremation]] grounds in the company of women of questionable [[virtue]]. In [[India]] generally the [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]] were not practiced in the [[monasteries]] because their practice was incompatible with the [[Vinaya]], the rules and [[vows]] incumbent upon a [[monk]]. |

| − | At first this was also the case in Tibet.This [[tradition]] which existed outside of but parallel to the [[monastic]] [[discipline]], was brought to [[Tibet]] in the eighth century by such accomplished [[Mahasiddha]]s as [[Padmasambhava]] and [[Vimalamitra]] and readily adopted as the principal practice in non-monastic [[Tantric]] circles led by such {{Wiki|individual}} as [[Nubchen Sangye Yeshe]] (gNubs-chen sangs-rgyas ye-shes, 9 cen. CE), who in contrast to the [[monks]] at [[Samye monastery]] went about in the guise of a [[Bonpo]] black hat sorcerer. Nubchen was a married [[Lama]], and he was not only a [[Tantric]] sorcerer and [[Wikipedia:Magician(paranormal)|magician]], but a learned [[scholar]] and translator. However, his work and the studies and translations of the [[Mahayoga Tantras]] (the technical designation for the [[Higher Tantras]] in the early period) of others like him went on out side of government control and sponsorship. Basically the translation and practice of the [[Sutra]]s and the [[Vinaya]], and to a very limited extent certain Lower [[Tantras]], was all that was sanctioned and financed by the [[Tibetan]] government. | + | At first this was also the case in Tibet.This [[tradition]] which existed outside of but parallel to the [[monastic]] [[discipline]], was brought to [[Tibet]] in the eighth century by such accomplished [[Mahasiddha]]s as [[Padmasambhava]] and [[Vimalamitra]] and readily adopted as the [[principal]] practice in non-monastic [[Tantric]] circles led by such {{Wiki|individual}} as [[Nubchen Sangye Yeshe]] ([[gNubs-chen sangs-rgyas ye-shes]], 9 cen. CE), who in contrast to the [[monks]] at [[Samye monastery]] went about in the guise of a [[Bonpo]] black hat sorcerer. [[Nubchen]] was a married [[Lama]], and he was not only a [[Tantric]] sorcerer and [[Wikipedia:Magician(paranormal)|magician]], but a learned [[scholar]] and [[translator]]. However, his work and the studies and translations of the [[Mahayoga Tantras]] (the technical designation for the [[Higher Tantras]] in the early period) of others like him went on out side of government control and sponsorship. Basically the translation and practice of the [[Sutra]]s and the [[Vinaya]], and to a very limited extent certain Lower [[Tantras]], was all that was sanctioned and financed by the [[Tibetan]] government. |

| − | This represented an official [[Buddhism]]. But the [[Higher Tantras]], the [[Mahayoga Tantras]] (early period) or [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]] (later period) represented something of an outlaw or underground {{Wiki|movement}} at first. The antinomian and libertine Gnostic sentiments of the [[Tantras]] and especially the abundant {{Wiki|sexual}} [[symbolism]] ([[deities]] copulating, exhortations to practice incest, etc.) were calculated to offend the sentiments of {{Wiki|polite}} {{Wiki|society}}. It was not that the [[Tibetan]] were puritanical as such; in [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|culture}} {{Wiki|sex}} is not something [[evil]]. It is a natural appetite like hunger and [[thirst]], and to be freely indulged without any [[guilt]]. But {{Wiki|sexual}} expression in public is discouraged, so at first images of copulating [[deities]] were not to be publicly displayed. Even in [[India]], were erotic [[symbolism]] was not so restricted, the [[Tantras]] were pre-eminently an [[esoteric]] [[tradition]]. But even there much of what was expressed in the [[Tantra]] was there for its shock value-- it is part of the method of the [[Tantras]] to take the {{Wiki|individual}} [[beyond]] his limitations. to break through all {{Wiki|social}} and [[monastic]] conventions. Therefore the abundance of antinomian statements that would shock the [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[morality]] of the [[Brahman]] priest and the [[Buddhist monk]]-- all this put into the {{Wiki|mouth}} of the [[Buddha]]. | + | This represented an official [[Buddhism]]. But the [[Higher Tantras]], the [[Mahayoga Tantras]] (early period) or [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]] (later period) represented something of an outlaw or underground {{Wiki|movement}} at first. The {{Wiki|antinomian}} and libertine Gnostic sentiments of the [[Tantras]] and especially the abundant {{Wiki|sexual}} [[symbolism]] ([[deities]] copulating, exhortations to practice [[incest]], etc.) were calculated to offend the sentiments of {{Wiki|polite}} {{Wiki|society}}. It was not that the [[Tibetan]] were puritanical as such; in [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|culture}} {{Wiki|sex}} is not something [[evil]]. It is a natural appetite like hunger and [[thirst]], and to be freely indulged without any [[guilt]]. But {{Wiki|sexual}} expression in public is discouraged, so at first images of copulating [[deities]] were not to be publicly displayed. Even in [[India]], were {{Wiki|erotic}} [[symbolism]] was not so restricted, the [[Tantras]] were pre-eminently an [[esoteric]] [[tradition]]. But even there much of what was expressed in the [[Tantra]] was there for its shock value-- it is part of the method of the [[Tantras]] to take the {{Wiki|individual}} [[beyond]] his limitations. to break through all {{Wiki|social}} and [[monastic]] conventions. Therefore the abundance of {{Wiki|antinomian}} statements that would shock the [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[morality]] of the [[Brahman]] priest and the [[Buddhist monk]]-- all this put into the {{Wiki|mouth}} of the [[Buddha]]. |

No wonder that in the [[Guhyasamaja Tantra]] when the assembly of [[monks]] hear the {{Wiki|real}} [[teaching]] of the [[Buddha]] announced, they faint [[dead]] away in horror. | No wonder that in the [[Guhyasamaja Tantra]] when the assembly of [[monks]] hear the {{Wiki|real}} [[teaching]] of the [[Buddha]] announced, they faint [[dead]] away in horror. | ||

[[File:Babhaha s.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Babhaha s.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

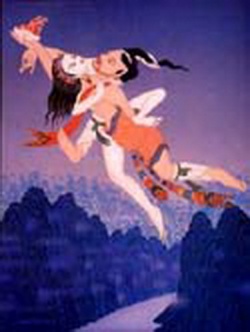

| − | :One might almost think of these [[Tantras]] as [[teaching]] a kind of [[Buddhist]] Satanism: the invocation of and {{Wiki|worship}} of a horned and hairy [[deity]] called a [[Heruka]], copulating with his [[goddess]] [[consort]], who eats raw flesh and drinks {{Wiki|blood}} while making thunderous {{Wiki|sounds}}, surrounded by nocturnal [[rites]] and orgies by {{Wiki|male}} and {{Wiki|female}} naked celebrants singing and [[dancing]], a veritable Witches' Sabbat. In the [[West]] in past centuries this was the perverse fantasy of [[celibate]] clerics and paranoid authorities-- a dark conspiracy against [[God]] and civil authority. Burning of heretics and culminated in the witch persecutions in which up to nine million [[people]] are said to have perished, burned at the stake or hanged. | + | :One might almost think of these [[Tantras]] as [[teaching]] a kind of [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Satanism}}: the invocation of and {{Wiki|worship}} of a horned and hairy [[deity]] called a [[Heruka]], copulating with his [[goddess]] [[consort]], who eats raw flesh and drinks {{Wiki|blood}} while making thunderous {{Wiki|sounds}}, surrounded by nocturnal [[rites]] and orgies by {{Wiki|male}} and {{Wiki|female}} naked celebrants singing and [[dancing]], a veritable Witches' Sabbat. In the [[West]] in {{Wiki|past}} centuries this was the perverse fantasy of [[celibate]] clerics and paranoid authorities-- a dark conspiracy against [[God]] and civil authority. Burning of {{Wiki|heretics}} and culminated in the witch persecutions in which up to nine million [[people]] are said to have perished, burned at the stake or hanged. |

| − | But the context in [[Buddhism]] and the use to which this chthonic and lunar [[symbolism]] is put is quite different. Here the [[aim]] is not to overthrow the established {{Wiki|church}} or the government of the [[king]], but the [[ignorant]] tyranny of the [[ego]], the false [[God]] and the false [[king]]. This lunar and chthonic [[symbolism]] of the [[Heruka]], the Horned [[God]], and the Witches' Sabbat is integrated into the [[spiritual]] [[path]] to [[enlightenment]]. What the whole [[world]] condemns becomes the very means to [[enlightenment]]. The forbidden fruit is tasted. And the method here is [[alchemical]] [[transformation]]. | + | But the context in [[Buddhism]] and the use to which this {{Wiki|chthonic}} and {{Wiki|lunar}} [[symbolism]] is put is quite different. Here the [[aim]] is not to overthrow the established {{Wiki|church}} or the government of the [[king]], but the [[ignorant]] tyranny of the [[ego]], the false [[God]] and the false [[king]]. This {{Wiki|lunar}} and {{Wiki|chthonic}} [[symbolism]] of the [[Heruka]], the Horned [[God]], and the Witches' Sabbat is integrated into the [[spiritual]] [[path]] to [[enlightenment]]. What the whole [[world]] condemns becomes the very means to [[enlightenment]]. The forbidden fruit is tasted. And the method here is [[alchemical]] [[transformation]]. |

: | : | ||

| − | :The [[Higher Tantras]] were underground in the early days, but translations were made, despite the lack of government sanction and sponsorship. And transmissions were received from [[Tantric]] [[masters]] who came to [[Tibet]], such as [[Guru Padmasambhava]] in the eighth century who taught the [[Tantric]] system of the [[Eight Herukas]] (bka'-brgyad), as well as [[Dzogchen]]. Three of these [[Herukas]] were [[worldly]] and concerned with [[magic]]: the [[Worldly]] [[Gods]], the [[Mamo]] mother [[goddesses]], and the Fierce [[Mantras]]. In their [[mandalas]] [[Padmasambhava]] even incorporated native [[Tibetan]] [[deities]] in a subordinate role. But he gave these [[initiations]] in a {{Wiki|cave}} at [[Chimphu]] and not in the nearby recently erected [[monastery]] of [[Samye]]. The {{Wiki|cult}} of the [[Higher Tantras]] was not practiced publicly. Wall paintings from these early centuries depict the [[peaceful]] [[deities]] of the [[Yoga Tantras]] but not the [[wrathful]] blood-drinking and copulating [[deities]] of the [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]]. | + | :The [[Higher Tantras]] were underground in the early days, but translations were made, despite the lack of government sanction and sponsorship. And [[transmissions]] were received from [[Tantric]] [[masters]] who came to [[Tibet]], such as [[Guru Padmasambhava]] in the eighth century who taught the [[Tantric]] system of the [[Eight Herukas]] ([[bka'-brgyad]]), as well as [[Dzogchen]]. Three of these [[Herukas]] were [[worldly]] and concerned with [[magic]]: the [[Worldly]] [[Gods]], the [[Mamo]] mother [[goddesses]], and the Fierce [[Mantras]]. In their [[mandalas]] [[Padmasambhava]] even incorporated native [[Tibetan]] [[deities]] in a subordinate role. But he gave these [[initiations]] in a {{Wiki|cave}} at [[Chimphu]] and not in the nearby recently erected [[monastery]] of [[Samye]]. The {{Wiki|cult}} of the [[Higher Tantras]] was not practiced publicly. Wall paintings from these early centuries depict the [[peaceful]] [[deities]] of the [[Yoga Tantras]] but not the [[wrathful]] blood-drinking and copulating [[deities]] of the [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]]. |

: | : | ||

| − | :When [[Buddhism]] was persecuted in [[Tibet]] in the ninth century after the assassination of the [[Buddhist]] [[king]] Ralpachan, it was only the [[monasteries]] and the [[monks]] that were suppressed. The faction in the government responsible for the coups was not anti-Buddhist as such (a later anachronistic interpretation) but felt that the [[monks]] were {{Wiki|social}} parasites and that the [[monasteries]] represented too great a drain on the {{Wiki|royal}} treasury at a [[time]] when foreign wars needed to be prosecuted to preserve the [[Tibetan]] [[empire]] in tact. {{Wiki|Individual}} [[Tantrikas]] or [[Tantric]] practitioners like [[Nubchen Sangye Yeshe]] continued their work and teachings privately without government interference. Although historical records a few and scanty, this period, the ninth and tenth centuries. is the seminal age for what subsequently became known as the schools of [[Nyingmapa]] and [[Yungdrung Bon]]. | + | :When [[Buddhism]] was persecuted in [[Tibet]] in the ninth century after the assassination of the [[Buddhist]] [[king]] [[Ralpachan]], it was only the [[monasteries]] and the [[monks]] that were suppressed. The faction in the government responsible for the coups was not anti-Buddhist as such (a later anachronistic interpretation) but felt that the [[monks]] were {{Wiki|social}} parasites and that the [[monasteries]] represented too great a drain on the {{Wiki|royal}} treasury at a [[time]] when foreign wars needed to be prosecuted to preserve the [[Tibetan]] [[empire]] in tact. {{Wiki|Individual}} [[Tantrikas]] or [[Tantric]] practitioners like [[Nubchen Sangye Yeshe]] continued their work and teachings privately without government interference. Although historical records a few and scanty, this period, the ninth and tenth centuries. is the seminal age for what subsequently became known as the schools of [[Nyingmapa]] and [[Yungdrung Bon]]. |

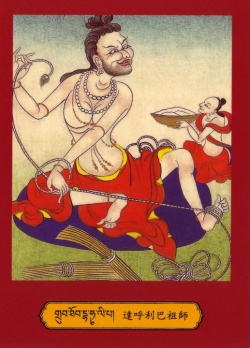

[[File:Dhahulipa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dhahulipa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | :Then in the eleventh century there was a revival of [[monastic]] [[Buddhism]] in Central and {{Wiki|Western}} [[Tibet]], initially under official government sponsorship in the {{Wiki|Western}} [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|kingdom}} of Guge. Inscription there of the {{Wiki|royal}} [[monks]] Lhalama Yeshe-od and his kinsman Dawa-od attack and condemn [[Dzogchen]] and the [[Mahayoga Tantras]], especially what is called sbyor-grol. sByor-ba refers to the practice of {{Wiki|sexual}} [[yoga]] and sgrol-ba to the killing of a [[living being]] in a [[ritual]] [[manner]] without incurring any negative [[karma]]. But in general, the [[Buddhist]] [[Tantras]], unlike the [[Hindu]] [[Tantras]] associated with the {{Wiki|cult}} of the [[goddess]] [[Kali]], do not involve actual {{Wiki|blood}} {{Wiki|sacrifice}}, although that [[symbolism]] may be employed. Both [[Buddhism]] and [[Yungdrung Bon]], unlike tribal [[shamanism]], categorically reject and condemn the practice of the red [[offering]] (dmar mchod) or {{Wiki|blood}} {{Wiki|sacrifice}}. But {{Wiki|sex}} is a different [[matter]] altogether. | + | :Then in the eleventh century there was a revival of [[monastic]] [[Buddhism]] in Central and {{Wiki|Western}} [[Tibet]], initially under official government sponsorship in the {{Wiki|Western}} [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|kingdom}} of [[Guge]]. Inscription there of the {{Wiki|royal}} [[monks]] [[Lhalama Yeshe-od]] and his kinsman [[Dawa-od]] attack and condemn [[Dzogchen]] and the [[Mahayoga Tantras]], especially what is called [[sbyor-grol]]. [[sByor-ba]] refers to the practice of {{Wiki|sexual}} [[yoga]] and [[sgrol-ba]] to the killing of a [[living being]] in a [[ritual]] [[manner]] without incurring any negative [[karma]]. But in general, the [[Buddhist]] [[Tantras]], unlike the [[Hindu]] [[Tantras]] associated with the {{Wiki|cult}} of the [[goddess]] [[Kali]], do not involve actual {{Wiki|blood}} {{Wiki|sacrifice}}, although that [[symbolism]] may be employed. Both [[Buddhism]] and [[Yungdrung Bon]], unlike tribal [[shamanism]], categorically reject and condemn the practice of the red [[offering]] ([[dmar mchod]]) or {{Wiki|blood}} {{Wiki|sacrifice}}. But {{Wiki|sex}} is a different [[matter]] altogether. |

| − | The [[Mahasiddhas]] in [[India]] and initially their followers in [[Tibet]] practiced {{Wiki|sexual}} [[yoga]], not just [[symbolically]] but actually. This however, scandalized many [[Tibetans]] who accused these [[Lamas]] of fornicating in the [[temples]]. When the great [[Indian]] [[Tantric]] [[master]] and [[scholar]] [[Atisha]] was invited to Guge in {{Wiki|Western}} [[Tibet]] in the eleventh century his own chief [[disciple]] [[Dromton]] forbade his [[master]] to teach the [[Higher Tantras]], claiming that the [[Tibetans]] would inevitably misunderstand their antinomianism and their {{Wiki|sexual}} [[symbolism]]. [[Dromton]] founded the first {{Wiki|distinct}} [[school]] of [[Tibetan Buddhism]], the [[Kadampa]], which was noted for its [[stress]] on the [[Vinaya]] or [[monastic]] [[discipline]]. | + | The [[Mahasiddhas]] in [[India]] and initially their followers in [[Tibet]] practiced {{Wiki|sexual}} [[yoga]], not just [[symbolically]] but actually. This however, scandalized many [[Tibetans]] who accused these [[Lamas]] of fornicating in the [[temples]]. When the great [[Indian]] [[Tantric]] [[master]] and [[scholar]] [[Atisha]] was invited to [[Guge]] in {{Wiki|Western}} [[Tibet]] in the eleventh century his own chief [[disciple]] [[Dromton]] forbade his [[master]] to teach the [[Higher Tantras]], claiming that the [[Tibetans]] would inevitably misunderstand their antinomianism and their {{Wiki|sexual}} [[symbolism]]. [[Dromton]] founded the first {{Wiki|distinct}} [[school]] of [[Tibetan Buddhism]], the [[Kadampa]], which was noted for its [[stress]] on the [[Vinaya]] or [[monastic]] [[discipline]]. |

: | : | ||

| − | :The [[Tibetan]] [[disciples]] of [[Atisha]] as well as other [[Tibetans]], some of whom went to [[India]] for studies, began building [[monasteries]]. In general [[Tibetans]] think that [[Buddhism]] only [[exists]] when there are [[monks]] and [[monasteries]], that is, a {{Wiki|social}} institution or {{Wiki|church}} which serves as the base for the [[transmission]] of the [[Buddhist teachings]]. But outside the [[monasteries]] and soon inside them the [[Mahasiddha]] [[Tradition]] continued to flourish and grow. The principal [[reason]] for this was that the [[Indian Buddhism]] of the [[time]] had become more and more dominated by [[Tantric]] practice. It was impossible for any of the [[Tibetan]] reformers, despite the new puritanism of the eleventh century to deny that the [[Higher Tantras]] were the [[word]] of the [[Buddha]]. | + | :The [[Tibetan]] [[disciples]] of [[Atisha]] as well as other [[Tibetans]], some of whom went to [[India]] for studies, began building [[monasteries]]. In general [[Tibetans]] think that [[Buddhism]] only [[exists]] when there are [[monks]] and [[monasteries]], that is, a {{Wiki|social}} institution or {{Wiki|church}} which serves as the base for the [[transmission]] of the [[Buddhist teachings]]. But outside the [[monasteries]] and soon inside them the [[Mahasiddha]] [[Tradition]] continued to flourish and grow. The [[principal]] [[reason]] for this was that the [[Indian Buddhism]] of the [[time]] had become more and more dominated by [[Tantric]] practice. It was impossible for any of the [[Tibetan]] reformers, despite the new puritanism of the eleventh century to deny that the [[Higher Tantras]] were the [[word]] of the [[Buddha]]. |

| − | The [[Higher Tantras]] were all the fashion in [[India]] and were taught to their [[Tibetan]] [[disciples]] by [[Indian]] [[masters]] such as [[Naropa]], [[Maitripa]], [[Atisha]], and so on. And so a reapproachment had to be made.The [[Higher Tantras]] could not be a congregational practice of [[monks]] because [[Tantric]] [[sadhana]], as well as {{Wiki|celebrations}} of the High [[Tantric]] feast or Ganachakrapuja, required partaking of meat, wine, and {{Wiki|sexual}} intercourse. | + | The [[Higher Tantras]] were all the fashion in [[India]] and were taught to their [[Tibetan]] [[disciples]] by [[Indian]] [[masters]] such as [[Naropa]], [[Maitripa]], [[Atisha]], and so on. And so a reapproachment had to be made.The [[Higher Tantras]] could not be a congregational practice of [[monks]] because [[Tantric]] [[sadhana]], as well as {{Wiki|celebrations}} of the High [[Tantric]] feast or [[Ganachakrapuja]], required partaking of meat, wine, and {{Wiki|sexual}} intercourse. |

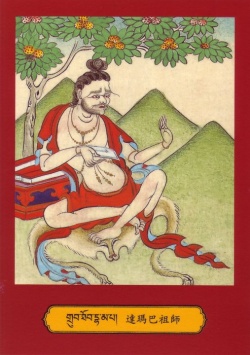

[[File:Dhamapa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dhamapa.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | At the very least the latter two would force a [[monk]] to break his [[vows]]. And so what came about in the eleventh century was a change in the [[external]] style of practice; the [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]], many of them freshly brought from [[India]] and newly translated into [[Tibetan]], came to be practiced in the style of the lower [[Yoga Tantras]]. Although there is a great deal of [[ritual]] in the [[Yoga Tantras]], there is [[nothing]] there that would require a [[monk]] to violate his [[monastic]] [[vows]]. The presence of a woman or [[Dakini]] is require at High [[Tantric]] [[initiation]] and also at the [[Tantric]] feast of the Ganachakrapuja, but in the eleventh century reform the actual [[Dakini]] {{Wiki|physically}} present was replaced by a mind-consort (yid kyi rig-ma), a [[visualization]] of the [[Dakini]]. One did the {{Wiki|sexual}} practice only in [[visualization]], not in actuality. In this way the practices of the [[Higher Tantras]] could be taken into the [[monasteries]] and incorporated into the congregations practice and liturgy of the [[monks]] known as [[puja]]. Unlike the [[Zen]] [[Buddhists]] of [[Japan]], [[Tibetan]] [[monks]] customarily do not practice group [[meditation]]. | + | At the very least the latter two would force a [[monk]] to break his [[vows]]. And so what came about in the eleventh century was a change in the [[external]] style of practice; the [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]], many of them freshly brought from [[India]] and newly translated into [[Tibetan]], came to be practiced in the style of the lower [[Yoga Tantras]]. Although there is a great deal of [[ritual]] in the [[Yoga Tantras]], there is [[nothing]] there that would require a [[monk]] to violate his [[monastic]] [[vows]]. The presence of a woman or [[Dakini]] is require at High [[Tantric]] [[initiation]] and also at the [[Tantric]] feast of the [[Ganachakrapuja]], but in the eleventh century reform the actual [[Dakini]] {{Wiki|physically}} {{Wiki|present}} was replaced by a [[mind-consort]] ([[yid kyi rig-ma]]), a [[visualization]] of the [[Dakini]]. One did the {{Wiki|sexual}} practice only in [[visualization]], not in [[actuality]]. In this way the practices of the [[Higher Tantras]] could be taken into the [[monasteries]] and incorporated into the congregations practice and liturgy of the [[monks]] known as [[puja]]. Unlike the [[Zen]] [[Buddhists]] of [[Japan]], [[Tibetan]] [[monks]] customarily do not practice group [[meditation]]. |

| − | That is something done in the privacy of one's room or in a [[retreat]] situation. The typical congregational practice of [[Tibetan]] [[monks]] is [[puja]] which may involve the [[chanting]] of liturgies and the making of [[offerings]] for many hours. Partaking of a little wine or meat during Ganapuja is allright because in the course of the [[ritual]] they have been mystically transmuted into nectars, and the {{Wiki|holy}} red and white {{Wiki|substances}} in the [[skull cup]] have been replaced by [[symbolic]] substitutes. But if one were to read the text of the liturgy, they are filled with the [[activities]] of [[wrathful deities]] which are both {{Wiki|sexual}} and sanguine. But otherwise, everything is perfect [[monastic]] [[decorum]]. This was so successful a solution to the dilemma that all [[four schools]] of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] almost exclusively practice the [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]], to the neglect of the [[Yoga Tantras]]. Nonetheless, the [[Yoga Tantra]] transmissions have been preserved, especially in the [[Sakyapa]] [[school]] which is quite fastidious about preserving all of the [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] [[Indian]] [[Tantric]] transmissions. Among the [[Nyingmapas]], who preserve the [[traditions]] coming from the early period of the spread of [[Buddhism]] in [[Tibet]] (7-9 cen. CE), practitioners of the [[Higher Tantras]] who do not take [[monastic]] [[ordination]] and become [[monks]] are known as [[Tantrikas]] or [[Ngagpas]] (sngags-pa), meaning "those who use [[mantras]] (sngags)". They are typically married [[Lamas]]. A [[Lama]], though functioning as a priest and [[teacher]], is not necessarily a [[monk]]. | + | That is something done in the privacy of one's room or in a [[retreat]] situation. The typical congregational practice of [[Tibetan]] [[monks]] is [[puja]] which may involve the [[chanting]] of liturgies and the making of [[offerings]] for many hours. Partaking of a little wine or meat during [[Ganapuja]] is allright because in the course of the [[ritual]] they have been mystically transmuted into nectars, and the {{Wiki|holy}} red and white {{Wiki|substances}} in the [[skull cup]] have been replaced by [[symbolic]] substitutes. But if one were to read the text of the liturgy, they are filled with the [[activities]] of [[wrathful deities]] which are both {{Wiki|sexual}} and sanguine. But otherwise, everything is perfect [[monastic]] [[decorum]]. This was so successful a solution to the {{Wiki|dilemma}} that all [[four schools]] of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] almost exclusively practice the [[Anuttara]] [[Tantras]], to the neglect of the [[Yoga Tantras]]. Nonetheless, the [[Yoga Tantra]] [[transmissions]] have been preserved, especially in the [[Sakyapa]] [[school]] which is quite fastidious about preserving all of the [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] [[Indian]] [[Tantric]] [[transmissions]]. Among the [[Nyingmapas]], who preserve the [[traditions]] coming from the early period of the spread of [[Buddhism]] in [[Tibet]] (7-9 cen. CE), practitioners of the [[Higher Tantras]] who do not take [[monastic]] [[ordination]] and become [[monks]] are known as [[Tantrikas]] or [[Ngagpas]] ([[sngags-pa]]), meaning "those who use [[mantras]] ([[sngags]])". They are typically married [[Lamas]]. A [[Lama]], though functioning as a priest and [[teacher]], is not necessarily a [[monk]]. |

Latest revision as of 04:20, 3 January 2014

- This Buddhist monastic culture was introduced into Tibet from India in the seventh and eighth centuries of our era, and revived again in the eleventh century after a temporary eclipse. The Indian Buddhist scholars brought with them to Tibet and exceptionally rich and profound thousand year old spiritual culture, and whereas this culture largely disappeared from India itself in the thirteenth century due to the total destruction of the great Buddhist monastic universities of Northern India by rampaging invading hordes from Afghanistan and Central Asia bent on pillage, loot, rape, and the forcible conversion of conquered native populations to the ascendant religion of Islam, much of the intellectual heritage of these universities, lost in India, was preserved in Tibet.

- During these early centuries the Tibetan government sponsored one of the greatest translations projects ever undertaken in history-- translating the bulk of texts of Mahayana Buddhism from the Sanskrit language into Tibetan. But although this monastic culture of monks and monasteries has been throughout the past 2500 years the principal social institution for the preservation and the transmission of the Buddhist heritage, that there have existed other forms of Buddhist teaching and practice.

- Even in the time of Shakyamuni Buddha himself, not all of his principle followers were monks. One example is the layman and merchant Vimalakirti who could defeat in debate on the subject of Shunyata or emptiness the great monk scholar Shariputra himself. Scholars such as E. Lamotte and E. Conze have speculated that the tension between the saffron robbed Elders of the monastic community and the white garbed leaders of the Buddhist lay community, was one factor in the historical development of the Mahayana.

Only a century after the passing away of the Lord Buddha, at or around the council at Vaishali there was a schism between the Sthaviras or Elders and the Mahasanghikas or adherents of the Greater Assembly, which included many leaders who were not monks. Whereas the traditions preserved among the Sthaviras or elder monks evolved into the eighteen schools of Hinayana Buddhism, which asserted that in order to attain liberation from the cycle of rebirth one must first be reborn as a male and second become a monk, the Mahasanghikas held the enlightenment was open to everyone, male or female, monk or lay-person, because each individual possessed an inner disposition to enlightenment.

This community of the Mahasanghikas was the matrix out of which the later Mahayana grew-- but both Sthaviras and Mahasanghikas possessed authentic traditions that went back to the historical Buddha himself, although their emphases differed. In the Mahasanghika-Mahayana tradition it was possible for the layman or the laywoman to be a full-fledged practitioner of the Buddha Dharma, and not just a second rate citizen of the Sangha in relation to the ordained clergy of the monks.

- But most important historically for the development of Buddhism in Tibet was the Mahasiddha Tradition that evolved in North India in the early Medieval Period (3-13 cen. CE). Philosophically this movement was based on the insights revealed in the Mahayana Sutras and as systematized in the Madhyamaka and Chittamatrin schools of philosophy, but the methods of meditation and practice were radically different than anything seen in the monasteries. The Sanskrit term Mahasiddha means a great adept.

A Siddha or adept is an individual who, through the practice of sadhana, a spiritual and psychic discipline or process of realization, attains the realization of siddhis, psychic and spiritual powers. These methods were revealed in Buddhist scriptures known as Tantras. Sometimes their source is said to be the historical Buddha, but more often it is a transhistorical aspect of the Buddha called Vajradhara who reveals the Tantra in question directly in a vision to a specific Mahasiddha. This vague and ill defined community of Mahasiddhas was the historical matrix for the revelation of the Higher Tantras, the Anuttara Tantras. They broke with the conventions of Buddhist monastic life of the time, and abandoning the monastery they practiced in the caves, the forests, and the country villages of Northern India. In complete contrast to the settled monastic establishment of their day, which concentrated the Buddhist intelligenzia in a limited number of large monastic universities, they adopted the life-style of itinerant mendicants, much the wandering Sadhus of modern India.

- The form of ascesis expounded in the Tantras, unlike the Sutras and the Vinaya which taught the methods of the path of renunciation, taught the methods of transformation, where the poisons of the passions, far from being renounced were actually cultivated to their extreme, in order that their energy might be transmuted within the alchemical vessel of the physical human body into the luminous nectar of enlightened awareness. There was a deliberate and clear parallel here with alchemy-- the kleshas or passions through the alchemical process of sadhana were transmuted into Jnana (gnosis) or knowledge. Thus the things of the world that are usually renounced by the ascetic-- wine, meat, and sex-- which are seen as the fetters binding the spirit to matter and nature, especially the latter (women and sex) are not renounced in the higher Tantras but actually employed as the very means to enlightenment. But this was not an excuse or rationale to party with wine, women, and song-- it represented a highly disciplined ascetic path. And since the methods of the Tantra principally works with energy, and one of the most important and powerful energies in human experience is sex desire, a sophisticated sexual yoga developed, known as Upayamarga and as Karmamudra.

Yoga practitioners took consorts or sexual partners from among the village girls, including even outcaste girls, such as Dombhis, Chandalis, etc. and lived with them in retreat or in the villages while plying humbles trades. For example, the young Brahman scholar Saraha defiled his caste status by living openly with a low caste who was an arrow-maker, yet he is considered one of the greatest poets and scholars of the Buddhist Tantric tradition. Or Naropa, once a professor and chancellor at Nalanda monastic university, abandoned his academic career to pursue the teachings of Tilopa, a wild-eyed and apparently half-mad ascetic who lived in a series of remote cremation grounds in the company of women of questionable virtue. In India generally the Anuttara Tantras were not practiced in the monasteries because their practice was incompatible with the Vinaya, the rules and vows incumbent upon a monk.

At first this was also the case in Tibet.This tradition which existed outside of but parallel to the monastic discipline, was brought to Tibet in the eighth century by such accomplished Mahasiddhas as Padmasambhava and Vimalamitra and readily adopted as the principal practice in non-monastic Tantric circles led by such individual as Nubchen Sangye Yeshe (gNubs-chen sangs-rgyas ye-shes, 9 cen. CE), who in contrast to the monks at Samye monastery went about in the guise of a Bonpo black hat sorcerer. Nubchen was a married Lama, and he was not only a Tantric sorcerer and magician, but a learned scholar and translator. However, his work and the studies and translations of the Mahayoga Tantras (the technical designation for the Higher Tantras in the early period) of others like him went on out side of government control and sponsorship. Basically the translation and practice of the Sutras and the Vinaya, and to a very limited extent certain Lower Tantras, was all that was sanctioned and financed by the Tibetan government.

This represented an official Buddhism. But the Higher Tantras, the Mahayoga Tantras (early period) or Anuttara Tantras (later period) represented something of an outlaw or underground movement at first. The antinomian and libertine Gnostic sentiments of the Tantras and especially the abundant sexual symbolism (deities copulating, exhortations to practice incest, etc.) were calculated to offend the sentiments of polite society. It was not that the Tibetan were puritanical as such; in Tibetan culture sex is not something evil. It is a natural appetite like hunger and thirst, and to be freely indulged without any guilt. But sexual expression in public is discouraged, so at first images of copulating deities were not to be publicly displayed. Even in India, were erotic symbolism was not so restricted, the Tantras were pre-eminently an esoteric tradition. But even there much of what was expressed in the Tantra was there for its shock value-- it is part of the method of the Tantras to take the individual beyond his limitations. to break through all social and monastic conventions. Therefore the abundance of antinomian statements that would shock the conventional morality of the Brahman priest and the Buddhist monk-- all this put into the mouth of the Buddha.

No wonder that in the Guhyasamaja Tantra when the assembly of monks hear the real teaching of the Buddha announced, they faint dead away in horror.

- One might almost think of these Tantras as teaching a kind of Buddhist Satanism: the invocation of and worship of a horned and hairy deity called a Heruka, copulating with his goddess consort, who eats raw flesh and drinks blood while making thunderous sounds, surrounded by nocturnal rites and orgies by male and female naked celebrants singing and dancing, a veritable Witches' Sabbat. In the West in past centuries this was the perverse fantasy of celibate clerics and paranoid authorities-- a dark conspiracy against God and civil authority. Burning of heretics and culminated in the witch persecutions in which up to nine million people are said to have perished, burned at the stake or hanged.

But the context in Buddhism and the use to which this chthonic and lunar symbolism is put is quite different. Here the aim is not to overthrow the established church or the government of the king, but the ignorant tyranny of the ego, the false God and the false king. This lunar and chthonic symbolism of the Heruka, the Horned God, and the Witches' Sabbat is integrated into the spiritual path to enlightenment. What the whole world condemns becomes the very means to enlightenment. The forbidden fruit is tasted. And the method here is alchemical transformation.

- The Higher Tantras were underground in the early days, but translations were made, despite the lack of government sanction and sponsorship. And transmissions were received from Tantric masters who came to Tibet, such as Guru Padmasambhava in the eighth century who taught the Tantric system of the Eight Herukas (bka'-brgyad), as well as Dzogchen. Three of these Herukas were worldly and concerned with magic: the Worldly Gods, the Mamo mother goddesses, and the Fierce Mantras. In their mandalas Padmasambhava even incorporated native Tibetan deities in a subordinate role. But he gave these initiations in a cave at Chimphu and not in the nearby recently erected monastery of Samye. The cult of the Higher Tantras was not practiced publicly. Wall paintings from these early centuries depict the peaceful deities of the Yoga Tantras but not the wrathful blood-drinking and copulating deities of the Anuttara Tantras.

- When Buddhism was persecuted in Tibet in the ninth century after the assassination of the Buddhist king Ralpachan, it was only the monasteries and the monks that were suppressed. The faction in the government responsible for the coups was not anti-Buddhist as such (a later anachronistic interpretation) but felt that the monks were social parasites and that the monasteries represented too great a drain on the royal treasury at a time when foreign wars needed to be prosecuted to preserve the Tibetan empire in tact. Individual Tantrikas or Tantric practitioners like Nubchen Sangye Yeshe continued their work and teachings privately without government interference. Although historical records a few and scanty, this period, the ninth and tenth centuries. is the seminal age for what subsequently became known as the schools of Nyingmapa and Yungdrung Bon.

- Then in the eleventh century there was a revival of monastic Buddhism in Central and Western Tibet, initially under official government sponsorship in the Western Tibetan kingdom of Guge. Inscription there of the royal monks Lhalama Yeshe-od and his kinsman Dawa-od attack and condemn Dzogchen and the Mahayoga Tantras, especially what is called sbyor-grol. sByor-ba refers to the practice of sexual yoga and sgrol-ba to the killing of a living being in a ritual manner without incurring any negative karma. But in general, the Buddhist Tantras, unlike the Hindu Tantras associated with the cult of the goddess Kali, do not involve actual blood sacrifice, although that symbolism may be employed. Both Buddhism and Yungdrung Bon, unlike tribal shamanism, categorically reject and condemn the practice of the red offering (dmar mchod) or blood sacrifice. But sex is a different matter altogether.

The Mahasiddhas in India and initially their followers in Tibet practiced sexual yoga, not just symbolically but actually. This however, scandalized many Tibetans who accused these Lamas of fornicating in the temples. When the great Indian Tantric master and scholar Atisha was invited to Guge in Western Tibet in the eleventh century his own chief disciple Dromton forbade his master to teach the Higher Tantras, claiming that the Tibetans would inevitably misunderstand their antinomianism and their sexual symbolism. Dromton founded the first distinct school of Tibetan Buddhism, the Kadampa, which was noted for its stress on the Vinaya or monastic discipline.

- The Tibetan disciples of Atisha as well as other Tibetans, some of whom went to India for studies, began building monasteries. In general Tibetans think that Buddhism only exists when there are monks and monasteries, that is, a social institution or church which serves as the base for the transmission of the Buddhist teachings. But outside the monasteries and soon inside them the Mahasiddha Tradition continued to flourish and grow. The principal reason for this was that the Indian Buddhism of the time had become more and more dominated by Tantric practice. It was impossible for any of the Tibetan reformers, despite the new puritanism of the eleventh century to deny that the Higher Tantras were the word of the Buddha.

The Higher Tantras were all the fashion in India and were taught to their Tibetan disciples by Indian masters such as Naropa, Maitripa, Atisha, and so on. And so a reapproachment had to be made.The Higher Tantras could not be a congregational practice of monks because Tantric sadhana, as well as celebrations of the High Tantric feast or Ganachakrapuja, required partaking of meat, wine, and sexual intercourse.

At the very least the latter two would force a monk to break his vows. And so what came about in the eleventh century was a change in the external style of practice; the Anuttara Tantras, many of them freshly brought from India and newly translated into Tibetan, came to be practiced in the style of the lower Yoga Tantras. Although there is a great deal of ritual in the Yoga Tantras, there is nothing there that would require a monk to violate his monastic vows. The presence of a woman or Dakini is require at High Tantric initiation and also at the Tantric feast of the Ganachakrapuja, but in the eleventh century reform the actual Dakini physically present was replaced by a mind-consort (yid kyi rig-ma), a visualization of the Dakini. One did the sexual practice only in visualization, not in actuality. In this way the practices of the Higher Tantras could be taken into the monasteries and incorporated into the congregations practice and liturgy of the monks known as puja. Unlike the Zen Buddhists of Japan, Tibetan monks customarily do not practice group meditation.

That is something done in the privacy of one's room or in a retreat situation. The typical congregational practice of Tibetan monks is puja which may involve the chanting of liturgies and the making of offerings for many hours. Partaking of a little wine or meat during Ganapuja is allright because in the course of the ritual they have been mystically transmuted into nectars, and the holy red and white substances in the skull cup have been replaced by symbolic substitutes. But if one were to read the text of the liturgy, they are filled with the activities of wrathful deities which are both sexual and sanguine. But otherwise, everything is perfect monastic decorum. This was so successful a solution to the dilemma that all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism almost exclusively practice the Anuttara Tantras, to the neglect of the Yoga Tantras. Nonetheless, the Yoga Tantra transmissions have been preserved, especially in the Sakyapa school which is quite fastidious about preserving all of the authentic Indian Tantric transmissions. Among the Nyingmapas, who preserve the traditions coming from the early period of the spread of Buddhism in Tibet (7-9 cen. CE), practitioners of the Higher Tantras who do not take monastic ordination and become monks are known as Tantrikas or Ngagpas (sngags-pa), meaning "those who use mantras (sngags)". They are typically married Lamas. A Lama, though functioning as a priest and teacher, is not necessarily a monk.

- But the old pre-Buddhist pagan and shamanic culture of Tibet continued side by side with the growth of this monastic system of Indian origin. Gradually, in all of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism these indigenous magical and ritual practices began integrated with the Buddhist practices of Indian origin, thus giving to Tibetan Buddhism its unique flavor and character which is so different from other forms of Mahayana Buddhism. The Ngakpas like Nubchen Sangye Yeshe, living outside the monasteries and still close to the common people of Tibet, the peasants and the nomads, were especially open to incorporating the native magical tradition into their Buddhism. The same had been done previously in India, incorporating the traditions of popular Indian magic into the Buddhist Tantras, as for example, the Mahakala Tantra. This was done by both Indian and Tibetan Buddhists for the simple reason that, on the practical level, magic works. Magic is a way of evoking and channeling energy in order to realize certain effects.

It does not work with the same efficiency as a mechanical device because its efficacy depends on the state of mind of the practitioner and may other secondary factors, but it works enough of the time to inspire the confidence of most of humanity for most of human history. However, in the West, since the eighteenth century with its mechanistic model of reality and the general fruitfulness of the scientific method and explanations, magic has received a bad press from Western scholars. Western scholars of Buddhism tend to underplay the role of magic in Buddhism, including Theravada Buddhism, and they become upset with the idea that Buddhist Tantra represents an incredibly complex and sophisticated system of theurgy and ceremonial magic.