Difference between revisions of "Madhyāntavibhāga"

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

[[Madhyānta-vibhāga-kārikā]] (Verses Distinguishing the Middle and the [[Extremes]]) is a key work in [[Yogācāra]] [[Buddhist]] [[philosophy]], attributed in the {{Wiki|Tibetan}} [[tradition]] to [[Maitreya-nātha]] and in other [[traditions]] to [[Asanga]]' | [[Madhyānta-vibhāga-kārikā]] (Verses Distinguishing the Middle and the [[Extremes]]) is a key work in [[Yogācāra]] [[Buddhist]] [[philosophy]], attributed in the {{Wiki|Tibetan}} [[tradition]] to [[Maitreya-nātha]] and in other [[traditions]] to [[Asanga]]' | ||

| − | The [[Madhyānta-vibhāga-kārikā]] consists of 112 | + | The [[Madhyānta-vibhāga-kārikā]] consists of 112 verses ([[kārikā]]) which [[delineate the distinctions]] ([[vibhāga]]) and relationship between the [[middle]] ([[madya]]) [[view]] and the [[extremes]] ([[anta]]); it contains five chapters: [[Attributes]] ([[laksana]]), [[Obscurations]] ([[āvarana]]), [[Reality]] ([[tattva]]), [[Cultivation of Antidotes]] ([[pratipaksa-bhāvanā]]) and the [[Supreme Way]] ([[yānānuttarya]]). Along with {{Wiki|Chinese}}, {{Wiki|Tibetan}} and {{Wiki|Mongolian}} translations, the text survives in a single {{Wiki|Sanskrit}} {{Wiki|manuscript}} discovered in {{Wiki|Tibet}} by the {{Wiki|Indian}} [[Buddhologist]] and explorer, {{Wiki|Rahul Sankrityayan}}. The [[Sanskrit]] version also included a [[commentary]] ([[bhāsya]]) by [[Vasubandhu]]. An important [[sub-commentary]] ([[tīkā]]) by [[Sthiramati]] also survives in [[Sanskrit]] as well as a {{Wiki|Tibetan}} version. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

[[Category:Yogacara]] | [[Category:Yogacara]] | ||

Revision as of 08:24, 26 January 2014

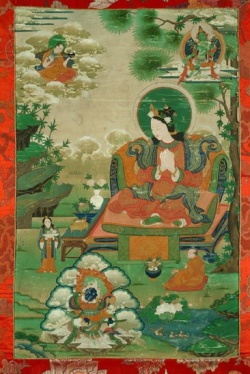

Madhyāntavibhāga by Maitreya-nātha (ca. 4th century) - a key work of Yogācāra Buddhist philosophy - based on the commentaries by Vasubandhu and Ju Mipham (1846–1912), which delineates the distinctions and relationship (vibhāga) between the middle view (madhya) and extremes (anta).

Maitreya's work speaks about the two sides of the same coin—mind in its confused state of daydreaming its own world versus waking up to its true nature. Like many other Yogacara scriptures, this text too describes the phenomenal world as being nothing but the product of our own essentially confused imagination and thus lacking any real existence outside of the imagining mind. The samsaric mind, which is ignorant about its own true nature, creates an imaginary split into subject and object and then becomes caught up in its own display of the subject grasping at all kinds of objects.

On the other hand, the nature of phenomena (or the mind) is described here in detail as the nonconceptual wisdom that lacks any duality of subject and object, but realizes its own primordially enlightened nature. This wisdom is not something newly produced through the path—it is said to exist primordially and is only obscured temporarily by adventitious stains (phenomena). Thus, its own natural state is always unchanging, just as the sun itself is never altered by the presence or absence of clouds. However, from the perspective of samsaric beings who do not realize mind's nature, it first seems to be obscured, thus appearing as the play of various dualistic phenomena, while later, its state seems to change into the pure awareness that is free of illusory dualistic creations.

Madhyānta-vibhāga-kārikā (Verses Distinguishing the Middle and the Extremes) is a key work in Yogācāra Buddhist philosophy, attributed in the Tibetan tradition to Maitreya-nātha and in other traditions to Asanga'

The Madhyānta-vibhāga-kārikā consists of 112 verses (kārikā) which delineate the distinctions (vibhāga) and relationship between the middle (madya) view and the extremes (anta); it contains five chapters: Attributes (laksana), Obscurations (āvarana), Reality (tattva), Cultivation of Antidotes (pratipaksa-bhāvanā) and the Supreme Way (yānānuttarya). Along with Chinese, Tibetan and Mongolian translations, the text survives in a single Sanskrit manuscript discovered in Tibet by the Indian Buddhologist and explorer, Rahul Sankrityayan. The Sanskrit version also included a commentary (bhāsya) by Vasubandhu. An important sub-commentary (tīkā) by Sthiramati also survives in Sanskrit as well as a Tibetan version.