Difference between revisions of "To Touch Enlightenment with the Body"

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Like many Westerners, I always assumed that [[meditation]] was a "[[spiritual]]" [[phenomenon]], which I took to mean that it somehow had to do with [[realms]] beyond the [[physical]]. For a long [[time]] I wasn’t {{Wiki|aware}} that I believed this, but in retrospect I see that I did. At the same [[time]], it is also obvious that [[meditation]] practice actually tended to lead me in the [[direction]] of deeper engagement with the [[physical]]. Especially in intensives or on [[retreat]], I would [[feel]] a considerable amount of [[physical]] discomfort, which I saw as an unfortunate and unnecessary diversion from what I was “really” supposed to be doing. I [[thought]] that if I could get rid of my discomfort, I would be able to progress more quickly in my practice. I didn’t have a very clear [[idea]] of what "progressing" might mean, but it definitely did not include [[physical]] {{Wiki|distress}}. So I tried a variety of stretching exercises, [[yoga]] techniques, [[body]] work and other [[bodily]] engagements that I [[thought]] might help me toward my goal of pain-free [[meditation]]. | Like many Westerners, I always assumed that [[meditation]] was a "[[spiritual]]" [[phenomenon]], which I took to mean that it somehow had to do with [[realms]] beyond the [[physical]]. For a long [[time]] I wasn’t {{Wiki|aware}} that I believed this, but in retrospect I see that I did. At the same [[time]], it is also obvious that [[meditation]] practice actually tended to lead me in the [[direction]] of deeper engagement with the [[physical]]. Especially in intensives or on [[retreat]], I would [[feel]] a considerable amount of [[physical]] discomfort, which I saw as an unfortunate and unnecessary diversion from what I was “really” supposed to be doing. I [[thought]] that if I could get rid of my discomfort, I would be able to progress more quickly in my practice. I didn’t have a very clear [[idea]] of what "progressing" might mean, but it definitely did not include [[physical]] {{Wiki|distress}}. So I tried a variety of stretching exercises, [[yoga]] techniques, [[body]] work and other [[bodily]] engagements that I [[thought]] might help me toward my goal of pain-free [[meditation]]. | ||

| − | Most [[meditators]] [[suffer]] from two kinds of [[physical]] problems. First, we [[experience]] specific weak points such as sore knees, lower back [[pain]], a kinky neck, tightness, tension or [[pain]] in the shoulders or upper back, and so on. Second, a | + | Most [[meditators]] [[suffer]] from two kinds of [[physical]] problems. First, we [[experience]] specific weak points such as sore knees, lower back [[pain]], a kinky neck, tightness, tension or [[pain]] in the shoulders or upper back, and so on. Second, a general achiness comes over our [[bodies]], particularly when we sit more intensively: everything seems to hurt at once—our {{Wiki|legs}} are aching, our shoulders and neck are sore, our back is on [[fire]]. It came as a disappointing [[realization]] one day that while I might be able to alleviate or shift the specific "[[hot]] spots,” the general achiness remained. In fact, it almost seemed that the more I was able to alleviate a specific complaint, the more achy my whole [[body]] became. I began to suspect that [[physical]] [[pain]] was just part of sitting on the cushion, at least for me. I found the prospect of [[endless]] [[physical]] [[pain]] dismal and depressing. |

And then, like many who find themselves in just the place I was, I made a surprising discovery. Somewhere in the timeless terrain of a dathun—a month-long [[meditation]] intensive—I had a particularly rough day. My whole [[body]] was a mass of pain—my ankles were stiff and crampy, my knees were sore, my {{Wiki|legs}} ached, and I had separate and {{Wiki|distinct}} complaints of [[pain]] in my lower, middle and upper back. We were in the middle of a long stretch of sitting, and my [[mind]] struggled mightily against the prospect of being trapped in this [[pain]] for an {{Wiki|indeterminate}} amount of [[time]]. My [[mental state]] became more and more sore and inflamed and gradually I arrived at a point when I felt that I really could not stand the [[pain]] of both my [[mind]] and my [[body]] another second. I was a nuclear reactor that had attained critical mass and was about to explode. If I have had an [[experience]] of [[hell]] in this [[life]], that moment of totally claustrophobic [[pain]] was it. | And then, like many who find themselves in just the place I was, I made a surprising discovery. Somewhere in the timeless terrain of a dathun—a month-long [[meditation]] intensive—I had a particularly rough day. My whole [[body]] was a mass of pain—my ankles were stiff and crampy, my knees were sore, my {{Wiki|legs}} ached, and I had separate and {{Wiki|distinct}} complaints of [[pain]] in my lower, middle and upper back. We were in the middle of a long stretch of sitting, and my [[mind]] struggled mightily against the prospect of being trapped in this [[pain]] for an {{Wiki|indeterminate}} amount of [[time]]. My [[mental state]] became more and more sore and inflamed and gradually I arrived at a point when I felt that I really could not stand the [[pain]] of both my [[mind]] and my [[body]] another second. I was a nuclear reactor that had attained critical mass and was about to explode. If I have had an [[experience]] of [[hell]] in this [[life]], that moment of totally claustrophobic [[pain]] was it. | ||

Revision as of 14:46, 20 March 2014

By Reginald Ray

In the second of a three-part series on Buddhism and the body, Reginald Ray talks about how the body is not just the pathway to realization but the embodiment of enlightenment itself.

Like many Westerners, I always assumed that meditation was a "spiritual" phenomenon, which I took to mean that it somehow had to do with realms beyond the physical. For a long time I wasn’t aware that I believed this, but in retrospect I see that I did. At the same time, it is also obvious that meditation practice actually tended to lead me in the direction of deeper engagement with the physical. Especially in intensives or on retreat, I would feel a considerable amount of physical discomfort, which I saw as an unfortunate and unnecessary diversion from what I was “really” supposed to be doing. I thought that if I could get rid of my discomfort, I would be able to progress more quickly in my practice. I didn’t have a very clear idea of what "progressing" might mean, but it definitely did not include physical distress. So I tried a variety of stretching exercises, yoga techniques, body work and other bodily engagements that I thought might help me toward my goal of pain-free meditation.

Most meditators suffer from two kinds of physical problems. First, we experience specific weak points such as sore knees, lower back pain, a kinky neck, tightness, tension or pain in the shoulders or upper back, and so on. Second, a general achiness comes over our bodies, particularly when we sit more intensively: everything seems to hurt at once—our legs are aching, our shoulders and neck are sore, our back is on fire. It came as a disappointing realization one day that while I might be able to alleviate or shift the specific "hot spots,” the general achiness remained. In fact, it almost seemed that the more I was able to alleviate a specific complaint, the more achy my whole body became. I began to suspect that physical pain was just part of sitting on the cushion, at least for me. I found the prospect of endless physical pain dismal and depressing.

And then, like many who find themselves in just the place I was, I made a surprising discovery. Somewhere in the timeless terrain of a dathun—a month-long meditation intensive—I had a particularly rough day. My whole body was a mass of pain—my ankles were stiff and crampy, my knees were sore, my legs ached, and I had separate and distinct complaints of pain in my lower, middle and upper back. We were in the middle of a long stretch of sitting, and my mind struggled mightily against the prospect of being trapped in this pain for an indeterminate amount of time. My mental state became more and more sore and inflamed and gradually I arrived at a point when I felt that I really could not stand the pain of both my mind and my body another second. I was a nuclear reactor that had attained critical mass and was about to explode. If I have had an experience of hell in this life, that moment of totally claustrophobic pain was it.

And then something abruptly shifted. All of a sudden I was utterly free of physical discomfort. I had not dissociated—in fact I was much more fully in my body than before—but somehow I let go of my resistance and struggle. I surrendered to the pain rather than continued to fight against it. My body responded by relaxing. I sat in utter peace, feeling the contentment of having a physical body—enjoying my breathing, feeling the pleasure of my heart beating and blood coursing through my veins, feeling the rich, complex, abundant life of energy going on within, fully present to the other meditators in the room and to the falling night outside.

That moment helped me to understand that the pain in my body was not an independent phenomenon, but was somehow tied up with my mind. When my mind changed, so did the feeling in my body. In fact, it seemed clear that my physical pain was a reflection of my mental state— a mental state characterized by ambition and aggression toward my body.

I also realized that our body is our early warning system, signaling us when our ambition is leading us to ignore and override the limitations of our physical situation. It is the blessing of our incarnation that the body can’t be fooled; in fact, it feels the full brunt of our driven behavior. A relatively mild message might be a pain in our neck or a sore back after a day when we are awash in struggle. In more extreme cases, serious disease may interrupt our way of handling our mind.

From the Buddhist point of view, these are all physical reflections of our mental situation, and, painful though they may be, are regarded as providing needed feedback we were unable to receive in any other way. They are welcome opportunities to grow. This is why Trungpa Rinpoche, for example, remarked that one should be grateful to have physical ailments to deal with. "Those who get sick are the lucky ones," he would say. If your neurosis doesn't affect your body, you will just keep pushing on in your current direction until your mind reaches a point of no return.

The body, it turns out, is an ally in meditation practice. Physical distress in sitting calls our mind away from its fantasies of spiritual attainment, and brings it back to the here and now. In Buddhism, this is known as synchronizing body and mind; through practice, our mind attunes itself more and more with the body, the concrete and earthy reality of our situation. This is the meaning of paying attention to the breath in meditation: we cultivate the ability to pay attention and be present to this subtle manifestation of our physicality. In mindfulness of breathing, we are training to surrender to the body.

But physical pain is often a more powerful, direct and unavoidable route to this than following the breath. There are many times in intensive meditation retreats when you are sitting hour after hour. Your body may be incredibly sore and tender—so much so, in fact, that you are not able to follow your breath, watch your thoughts, or do anything else that might be considered "meditation." You sit there and the only thing going on is just being with the pain, the discomfort, the fatigue, the hunger or whatever physical distress you may be feeling. Rather than saying that in those moments we are unable to meditate, I think it would be more accurate to say that we are practicing "mindfulness of the body." We are meditating on the body because it is beyond us to do anything else. The most powerful and transformative periods in a dathun occur in the fiery furnace of meditation sessions where this is going on.

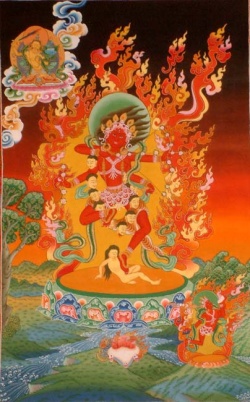

The more deeply one journeys into the world of meditation, the more one finds oneself working with the body. At a certain point, the body seems to be the main thing you are working with. For example, one of the most advanced Tibetan teachings—taken up after many years of beginning and intermediate meditation—is the practice of the inner yogas, sometimes known as the Six Yogas of Naropa. These involve using breathing exercises and yogic practices to explore more and more subtle levels of the body. The more refined one's knowledge of the body, the more the body reveals itself as transparent to the fundamental essence of its being. This essence is nothing other than the basic nature of mind itself. The more deeply you probe the body, the more you come to understand it as the energy and awareness of the awakened state itself. This is, in the evocative language of early Buddhism, to "touch enlightenment with the body."

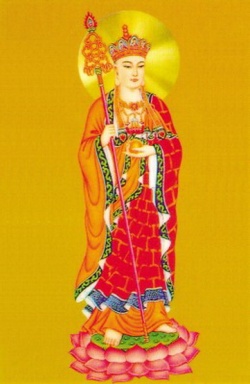

But in order to do this, we have to take our bodies seriously as spiritual reality. The great Buddhist saint Saraha remarked, "In my wanderings, I have visited shrines and other places of pilgrimage, but I have not seen another shrine as blissful as my body." We need to realize that our body is not a beginning point, not a jumping off point to something else. Rather, the body is itself the pathway to realization, and, at its deepest level, the embodiment of enlightenment itself. To know the body is to meet the awakened state. This is why Trungpa Rinpoche said, "There is no division between the spirituality of the mind and the spirituality of the body; they are both the same…." He commented further that the definition of samsara is a mind that parts company with the body. The definition of an awakened person is one for whom there is no separation of mind and body. To know the body is to know awareness. To know awareness in its pure state is to know the awakened state.

Reginald A. Ray, Ph.D., is Professor of Buddhist Studies at Naropa University and teacher in residence at Shambhala Mountain Center. His most recent book is Secret of the Vajra World: The Tantric Buddhism of Tibet.