Difference between revisions of "Manas (early Buddhism)"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

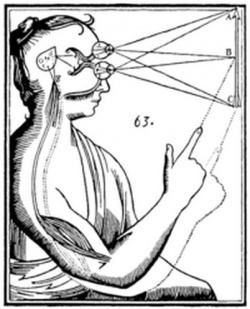

[[File:Cartes.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Cartes.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Manas]] ([[Pali]]) is one of three overlapping terms used in the [[nikayas]] to refer to the [[mind]], the others being [[citta]] and [[viññāṇa]]. Each is sometimes used in the generic and non-technical [[sense]] of "[[mind]]" in general, and the three are sometimes used in sequence to refer to one’s [[mental]] {{Wiki|processes}} as a whole. Their primary uses are, however, {{Wiki|distinct}}. | + | [[Manas]] ([[Pali]]) The [[name]] of the [[seventh consciousness]] of the [[eight consciousnesses]] refers to the {{Wiki|faculty}} of [[thought]], the [[intellectual function of consciousness]].is one of three overlapping terms used in the [[nikayas]] to refer to the [[mind]], the others being [[citta]] and [[viññāṇa]]. Each is sometimes used in the generic and non-technical [[sense]] of "[[mind]]" in general, and the three are sometimes used in sequence to refer to one’s [[mental]] {{Wiki|processes}} as a whole. Their primary uses are, however, {{Wiki|distinct}}. |

| − | [[Manas]] often indicates the general [[thinking]] | + | [[Manas]] often indicates the general [[thinking faculty]]. [[Thinking]] is closely associated with [[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volitions]], because [[mental activity]] is one of the ways that [[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volitions]] [[manifest]] themselves: "Having willed, one acts through [[body]], [[speech]], and [[thoughts]]." Furthermore, willing is described in terms of deliberate [[thinking]]. |

| − | Undeliberate [[thought]] is often an expression of latent tendencies ([[anusaya]]), which are [[conditioned]] by the [[volitional]] nexus of the {{Wiki|past}}. | + | Undeliberate [[thought]] is often an expression of latent {{Wiki|tendencies}} ([[anusaya]]), which are [[conditioned]] by the [[volitional]] nexus of the {{Wiki|past}}. |

| − | The term is not used in the description of the {{Wiki|cognitive}} process in the early texts, aside from the preliminary role of [[manodhātu]]. The discursive [[activities]] of the {{Wiki|cognitive}} process are rather the [[function]] of [[saññā]], together with "{{Wiki|reasoning}}" and "making manifold". This suggests that the "[[thinking]]" done by [[manas]] is more closely linked to [[volition]] than to the discursive {{Wiki|processes}} associated with {{Wiki|apperception}}. [[Manas]] is mainly the [[mental | + | The term is not used in the description of the {{Wiki|cognitive}} process in the early texts, aside from the preliminary role of [[manodhātu]]. The discursive [[activities]] of the {{Wiki|cognitive}} process are rather the [[function]] of [[saññā]], together with "{{Wiki|reasoning}}" and "making manifold". This suggests that the "[[thinking]]" done by [[manas]] is more closely linked to [[volition]] than to the discursive {{Wiki|processes}} associated with {{Wiki|apperception}}. [[Manas]] is mainly the [[mental activity]] which follows from [[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volitions]], whether immediately, or separated by [[time]] and [[caused]] by the activation of a latent tendency. |

Revision as of 04:25, 22 March 2014

Manas (Pali) The name of the seventh consciousness of the eight consciousnesses refers to the faculty of thought, the intellectual function of consciousness.is one of three overlapping terms used in the nikayas to refer to the mind, the others being citta and viññāṇa. Each is sometimes used in the generic and non-technical sense of "mind" in general, and the three are sometimes used in sequence to refer to one’s mental processes as a whole. Their primary uses are, however, distinct.

Manas often indicates the general thinking faculty. Thinking is closely associated with volitions, because mental activity is one of the ways that volitions manifest themselves: "Having willed, one acts through body, speech, and thoughts." Furthermore, willing is described in terms of deliberate thinking.

Undeliberate thought is often an expression of latent tendencies (anusaya), which are conditioned by the volitional nexus of the past.

The term is not used in the description of the cognitive process in the early texts, aside from the preliminary role of manodhātu. The discursive activities of the cognitive process are rather the function of saññā, together with "reasoning" and "making manifold". This suggests that the "thinking" done by manas is more closely linked to volition than to the discursive processes associated with apperception. Manas is mainly the mental activity which follows from volitions, whether immediately, or separated by time and caused by the activation of a latent tendency.