Difference between revisions of "The Yogacara Lineage"

m (1 revision: Robo 2.48 15 septmeber replacetext) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Asanga -55lk.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Asanga -55lk.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | The [[wisdom]] teachings of the [[Mahayana]] are contained in three [[primary]] sets of writings. The first and oldest of these are the [[Prajnaparamita]] texts, which date to the beginning of the current {{Wiki|era}}. These [[wisdom]] texts go beyond conventional understanding and speak directly to one’s innate [[enlightened]] nature. They are the first pointing out texts –transmitting the [[transcendent]] [[wisdom]] that sees the [[emptiness]] of all [[conceptualized]] [[views]] of [[reality]]. | + | The [[wisdom]] teachings of the [[Mahayana]] are contained in three [[primary]] sets of writings. The first and oldest of these are the [[Prajnaparamita]] texts, which date to the beginning of the current {{Wiki|era}}. These [[wisdom]] texts go beyond [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[understanding]] and speak directly to one’s innate [[enlightened]] [[nature]]. They are the first pointing out texts –transmitting the [[transcendent]] [[wisdom]] that sees the [[emptiness]] of all [[conceptualized]] [[views]] of [[reality]]. |

| − | Later, Nargarjuna applied the insights of the [[Prajnaparamita]] to classical [[Indian philosophy]] and through his articulation of the nature of [[emptiness]] beautifully and impeccably dismantled prevailing scholastic [[views]] on the nature of [[reality]], establishing the primacy of the inexpressible as the [[heart]] of the [[Buddhist path]]. In the [[Mahayana]] [[tradition]] Nargarjuna is seen as the [[primary]] spokesperson of the Pranjaparamita {{Wiki|literature}}. | + | Later, [[Nargarjuna]] applied the [[insights]] of the [[Prajnaparamita]] to classical [[Indian philosophy]] and through his articulation of the [[nature]] of [[emptiness]] beautifully and impeccably dismantled prevailing {{Wiki|scholastic}} [[views]] on the [[nature]] of [[reality]], establishing the primacy of the inexpressible as the [[heart]] of the [[Buddhist path]]. In the [[Mahayana]] [[tradition]] [[Nargarjuna]] is seen as the [[primary]] spokesperson of the Pranjaparamita {{Wiki|literature}}. |

| − | These teachings were united with the [[meditative]] and devotional [[traditions]] of [[Mahayana]] by a brilliant set of [[teachers]] from [[Gandhara]], [[Asanga]] and [[Vasubandu]], whose works are the culmination of the early [[Mahayana]] movement. The school that held this [[transmission]] [[tradition]] was [[Yogacara]], which became the leading [[philosophical]] school in [[India]] during the 3rd to 5th centuries, at the same [[time]] that {{Wiki|Neoplatonism}} was the leading [[philosophical]] school in the Classical Western [[World]]. [[Yogacara]] teachings still [[form]] the [[philosophical]] core of the great [[Buddhist]] contemplative [[lineages]] such as [[Zen]], [[Mahamudra]] and [[Dzogchen]]. In a similar [[manner]] {{Wiki|Neoplatonism}} underlines Western contemplative [[lineages]]. | + | These teachings were united with the [[meditative]] and devotional [[traditions]] of [[Mahayana]] by a brilliant set of [[teachers]] from [[Gandhara]], [[Asanga]] and [[Vasubandu]], whose works are the culmination of the early [[Mahayana]] {{Wiki|movement}}. The school that held this [[transmission]] [[tradition]] was [[Yogacara]], which became the leading [[philosophical]] school in [[India]] during the 3rd to 5th centuries, at the same [[time]] that {{Wiki|Neoplatonism}} was the leading [[philosophical]] school in the Classical {{Wiki|Western}} [[World]]. [[Yogacara]] teachings still [[form]] the [[philosophical]] core of the great [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|contemplative}} [[lineages]] such as [[Zen]], [[Mahamudra]] and [[Dzogchen]]. In a similar [[manner]] {{Wiki|Neoplatonism}} underlines {{Wiki|Western}} {{Wiki|contemplative}} [[lineages]]. |

| − | [[Yogacara]] translates as “practitioners of [[yoga]]” emphasizing the school’s commitment to [[meditation]] as the [[essential]] nature of the [[Buddhist path]]. It is also known as the [[Consciousness Only]] School for their central [[teaching]] that all [[reality]] is a display of [[consciousness]]. | + | [[Yogacara]] translates as “practitioners of [[yoga]]” {{Wiki|emphasizing}} the school’s commitment to [[meditation]] as the [[essential]] [[nature]] of the [[Buddhist path]]. It is also known as the [[Consciousness Only]] School for their central [[teaching]] that all [[reality]] is a display of [[consciousness]]. |

[[File:Asanga -ups.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Asanga -ups.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

[[Asanga]] | [[Asanga]] | ||

| − | According to the [[Tibetan tradition]], [[Asanga]] was born in Purusapura, the capital of [[Gandhara]], of a [[Brahmin]] woman who was herself a considerable adept in the teachings of [[Buddhism]] and who taught him the “eighteen | + | According to the [[Tibetan tradition]], [[Asanga]] was born in [[Purusapura]], the capital of [[Gandhara]], of a [[Brahmin]] woman who was herself a considerable {{Wiki|adept}} in the teachings of [[Buddhism]] and who [[taught]] him the “eighteen {{Wiki|sciences}}” which he mastered easily. He became a [[monk]] and for five years applied himself diligently, memorizing one hundred thousand verses of [[dharma]] each year and correctly [[understanding]] their meaning. |

He then left the [[monastery]] to practice the [[Arya]] [[Maitreya]] [[Sadhana]] in a {{Wiki|cave}} at the foot of a mountain. For three years, not a single good sign appeared, and he became depressed and decided to leave his [[retreat]]. [[Emerging]] from his {{Wiki|cave}} he noticed a bird’s nest by the mountain where the rock had become worn just by the brushing of the bird’s wing as it flew back and forth. [[Realizing]] his perseverance was weak, he returned to his {{Wiki|cave}} to practice. For three more years he [[meditated]], but again not a single good sign appeared. He became discouraged and left again. This [[time]] he saw a rock beside the road that was slowly disintegrating because of the trickle of single drops of [[water]]. Inspired by this, he returned and practiced another three years. | He then left the [[monastery]] to practice the [[Arya]] [[Maitreya]] [[Sadhana]] in a {{Wiki|cave}} at the foot of a mountain. For three years, not a single good sign appeared, and he became depressed and decided to leave his [[retreat]]. [[Emerging]] from his {{Wiki|cave}} he noticed a bird’s nest by the mountain where the rock had become worn just by the brushing of the bird’s wing as it flew back and forth. [[Realizing]] his perseverance was weak, he returned to his {{Wiki|cave}} to practice. For three more years he [[meditated]], but again not a single good sign appeared. He became discouraged and left again. This [[time]] he saw a rock beside the road that was slowly disintegrating because of the trickle of single drops of [[water]]. Inspired by this, he returned and practiced another three years. | ||

| − | When again no signs appeared, he left his [[retreat]] a third [[time]]. He encountered an old man who was rubbing a piece of iron with a smooth cotton cloth. “I am just finishing this needle,” the man said to [[Asanga]]. “I have already made those over there” and pointed to small pile of needles lying nearby. [[Asanga]] [[thought]], “If such [[effort]] is put into a [[mundane]] task such as this, my [[effort]] so far has been merely a trifle.” | + | When again no [[signs]] appeared, he left his [[retreat]] a third [[time]]. He encountered an old man who was rubbing a piece of {{Wiki|iron}} with a smooth cotton cloth. “I am just finishing this needle,” the man said to [[Asanga]]. “I have already made those over there” and pointed to small pile of needles {{Wiki|lying}} nearby. [[Asanga]] [[thought]], “If such [[effort]] is put into a [[mundane]] task such as this, my [[effort]] so far has been merely a trifle.” |

[[File:Asanga 527.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Asanga 527.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | He returned and [[meditated]] for another three years. Although he had by now [[meditated]] for 12 years on [[Maitreya]], he still had no signs of favor. He became extremely despondent and walked away from his {{Wiki|cave}}. After awhile he came across a half-dead dog lying beside the road, infested with maggots, crying out in [[pain]]. [[Asanga]] [[thought]], “This dog will [[die]] if these worms are not removed, but if I try to lift them out with my hand, I will crush them.” So using his {{Wiki|tongue}} so as not to hurt them, and cutting off some of his own flesh for them to [[live]] in, he bent down to remove them. At that moment the dog vanished and [[Maitreya]] appeared, showering cascades of [[light]] in all [[directions]]. | + | He returned and [[meditated]] for another three years. Although he had by now [[meditated]] for 12 years on [[Maitreya]], he still had no [[signs]] of favor. He became extremely despondent and walked away from his {{Wiki|cave}}. After awhile he came across a half-dead {{Wiki|dog}} {{Wiki|lying}} beside the road, infested with maggots, crying out in [[pain]]. [[Asanga]] [[thought]], “This {{Wiki|dog}} will [[die]] if these worms are not removed, but if I try to lift them out with my hand, I will crush them.” So using his {{Wiki|tongue}} so as not to hurt them, and cutting off some of his own flesh for them to [[live]] in, he bent down to remove them. At that moment the {{Wiki|dog}} vanished and [[Maitreya]] appeared, showering cascades of [[light]] in all [[directions]]. |

| − | [[Asanga]] burst into tears and cried, | + | [[Asanga]] burst into {{Wiki|tears}} and cried, “[[Ah]], my sole [[teacher]] and [[refuge]], all those years I made so much [[effort]] in my practice, exerting myself in a hundred different ways, but I saw [[nothing]]. Why has the [[rain]] and the might of the ocean come only now when tormented by [[pain]], I am no longer thirsting?” [[Maitreya]] replied, “In [[truth]], I was in your presence constantly, yet because of [[karmic]] {{Wiki|obscuration}} you were unable to see me. However, your practice has [[purified]] your [[karma]] and removed your [[obstacles]]. Now by the force of your [[great compassion]] you are able to meet me. To test my words, put me on you shoulders for others to see and carry me across the city.” |

| − | [[Asanga]] was overjoyed. Lifting [[Maitreya]] onto his shoulders carried him into town, yet no one saw [[Maitreya]]. One old woman saw [[Asanga]] was carrying a [[dead]] dog and that brought her endless good [[fortune]]. A faithful servant saw Maitreya’s feet and found himself in a state of [[samadhi]] which granted him all the [[siddhis]]. [[Asanga]] himself [[realized]] the [[samadhi]] called “{{Wiki|Continuum}} of [[Reality]]”. “What is your [[desire]] now?” [[Maitreya]] asked him. “To revive the teachings of the [[Mahayana]],” [[Asanga]] replied. “Well then, hold onto the end of my robe.” [[Asanga]] did this and together they ascended to the [[pure land]] of [[Tushita]] where they stayed for fifty years. Here [[Asanga]] mastered the teachings of the [[Mahayana]] and received the famous Five Texts of [[Maitreya]], each of which opens a different door of [[samadhi]]. | + | [[Asanga]] was overjoyed. Lifting [[Maitreya]] onto his shoulders carried him into town, yet no one saw [[Maitreya]]. One old woman saw [[Asanga]] was carrying a [[dead]] {{Wiki|dog}} and that brought her [[endless]] good [[fortune]]. A faithful servant saw [[Maitreya’s]] feet and found himself in a state of [[samadhi]] which granted him all the [[siddhis]]. [[Asanga]] himself [[realized]] the [[samadhi]] called “{{Wiki|Continuum}} of [[Reality]]”. “What is your [[desire]] now?” [[Maitreya]] asked him. “To revive the teachings of the [[Mahayana]],” [[Asanga]] replied. “Well then, hold onto the end of my robe.” [[Asanga]] did this and together they ascended to the [[pure land]] of [[Tushita]] where they stayed for fifty years. Here [[Asanga]] mastered the teachings of the [[Mahayana]] and received the famous Five Texts of [[Maitreya]], each of which opens a different door of [[samadhi]]. |

| − | Dedicated to actualizing these teachings, [[Asanga]] returned to the [[earth]] and built a small [[temple]] in a forest. At first only a few students came to learn teachings from him, but gradually the [[fame]] of his [[doctrine]] spread and the [[Yogacara]] School was established. He became the [[abbot]] of [[Nalanda]] and lived to be well over 100, but always had a youthful look, with no gray [[hair]] or wrinkles. | + | Dedicated to actualizing these teachings, [[Asanga]] returned to the [[earth]] and built a small [[temple]] in a {{Wiki|forest}}. At first only a few students came to learn teachings from him, but gradually the [[fame]] of his [[doctrine]] spread and the [[Yogacara]] School was established. He became the [[abbot]] of [[Nalanda]] and lived to be well over 100, but always had a youthful look, with no gray [[hair]] or wrinkles. |

[[File:Asanga-78o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Asanga-78o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | He compiled many important [[Mahayana]] works including what has come to be known as The Five Texts of [[Maitreya]]. These include the Abhisamayalamkara (Ornament of Clear [[Comprehension]]), the Mahanaya Sutralankara (Ornament of the [[Mahayana Sutras]]), the Madhyanta-vibhanga ({{Wiki|Discourse}} on the Middle between the [[Extremes]]), the Dharma-dharmata-vibhaga, and the Uttaratantra (The Peerless {{Wiki|Continuum}}). His Mahayana-samparigraha (Compendium of the [[Mahayana]]), Abhidarma-samuccaya (Compendium of Higher [[Doctrine]]), and Yogacharabhumi-shastra (Treatise on the Stages of [[Yoga]] Practice) are also famous. | + | He compiled many important [[Mahayana]] works including what has come to be known as The Five Texts of [[Maitreya]]. These include the [[Abhisamayalamkara]] (Ornament of Clear [[Comprehension]]), the Mahanaya [[Sutralankara]] (Ornament of the [[Mahayana Sutras]]), the Madhyanta-vibhanga ({{Wiki|Discourse}} on the Middle between the [[Extremes]]), the [[Dharma-dharmata-vibhaga]], and the [[Uttaratantra]] (The Peerless {{Wiki|Continuum}}). His Mahayana-samparigraha (Compendium of the [[Mahayana]]), Abhidarma-samuccaya (Compendium of Higher [[Doctrine]]), and Yogacharabhumi-shastra (Treatise on the Stages of [[Yoga]] Practice) are also famous. |

| − | According to the [[Tibetan]] historian [[Taranatha]], [[Tantric teachings]] were handed down in secret through the [[Yogacara]] [[lineage]] from the [[time]] of [[Asanga]]. In the [[Tibetan canon]] are several [[Tantric]] works ascribed to [[Asanga]] including a [[Maitreya]] [[Sadhana]] and a Prajna-Paramita [[Sadhana]]. | + | According to the [[Tibetan]] historian [[Taranatha]], [[Tantric teachings]] were handed down in secret through the [[Yogacara]] [[lineage]] from the [[time]] of [[Asanga]]. In the [[Tibetan canon]] are several [[Tantric]] works ascribed to [[Asanga]] including a [[Maitreya]] [[Sadhana]] and a [[Prajna-Paramita]] [[Sadhana]]. |

[[Vasubandu]] | [[Vasubandu]] | ||

| − | The cofounder of [[Yogacara]], [[Vasubandu]], is [[traditionally]] said to be the younger brother of [[Asanga]]. He was also born in Purusapura in [[Gandhara]] and became a [[monk]] of the [[Sarvastivadin]] school. He went to [[Kashmir]] to study their teachings including their renown [[Abhidharma]] works. He also was said to possess a complete understanding of the [[Tripitaka]] and the tenets of all the [[Hinayana]] schools. | + | The cofounder of [[Yogacara]], [[Vasubandu]], is [[traditionally]] said to be the younger brother of [[Asanga]]. He was also born in [[Purusapura]] in [[Gandhara]] and became a [[monk]] of the [[Sarvastivadin]] school. He went to [[Kashmir]] to study their teachings including their renown [[Abhidharma]] works. He also was said to possess a complete [[understanding]] of the [[Tripitaka]] and the {{Wiki|tenets}} of all the [[Hinayana]] schools. |

| − | [[Vasubandu]] wrote Seven Branches of [[Metaphysics]], an encyclopedic work clarifying the main points of teachings of the early [[Arhats]], The Four Oral [[Traditions]] of [[Vinaya]] on [[Buddhist]] [[discipline]], and the most famous compendium of [[Abhidharma]] teachings in the [[Buddhist tradition]], the [[Abhidharma-kosa]] and a commentary to it called the Abhidharma-kosa-Bhayasa. The Kosa describes the [[Buddhist path]] to [[enlightenment]] by categorizing and analyzing the basic factors of [[experience]] called [[dharmas]]. | + | [[Vasubandu]] wrote [[Seven Branches]] of [[Metaphysics]], an {{Wiki|encyclopedic}} work clarifying the main points of teachings of the early [[Arhats]], The Four Oral [[Traditions]] of [[Vinaya]] on [[Buddhist]] [[discipline]], and the most famous compendium of [[Abhidharma]] teachings in the [[Buddhist tradition]], the [[Abhidharma-kosa]] and a commentary to it called the Abhidharma-kosa-Bhayasa. The [[Kosa]] describes the [[Buddhist path]] to [[enlightenment]] by categorizing and analyzing the basic factors of [[experience]] called [[dharmas]]. |

[[File:Vasubandhu336.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Vasubandhu336.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Already famous for his [[intellectual]] understanding of [[Buddhism]], [[Vasubandu]] came to [[Nalanda University]] and was converted to the [[Mahayana]] by [[Asanga]]. According to a [[traditional]] account, [[Asanga]] summoned [[Vasubandu]] under the pretext that he was dying. When [[Vasubandu]] arrived and asked the [[cause]] of his illness, [[Asanga]] replied, “I have a serious disease of the [[heart]] which arose on account of you.” [[Vasubandu]] asked, “How did it arise on account of me?” [[Asanga]] replied, “Because you do not believe in the [[Mahayana]] and are forever attacking and criticizing it. For this wickedness you will be [[reborn]] in a [[miserable]] [[existence]]. Grieving for you has brought me close to [[death]].” [[Vasubandu]] was surprised at this and asked [[Asanga]] to expound the [[Mahayana]] to him. Upon doing so he became convinced of the [[truth]] of the [[Mahayana]] and asked his brother what he could do to overcome the negative [[karma]] he had accumulated. [[Asanga]] answered, “Since your [[skillful]] and eloquent [[speech]] against the [[Mahayana]] earned you this negative [[karma]], you must now use your [[skillful]] and eloquent [[speech]] to propound the [[Mahayana]].” | + | Already famous for his [[intellectual]] [[understanding]] of [[Buddhism]], [[Vasubandu]] came to [[Nalanda University]] and was converted to the [[Mahayana]] by [[Asanga]]. According to a [[traditional]] account, [[Asanga]] summoned [[Vasubandu]] under the pretext that he was dying. When [[Vasubandu]] arrived and asked the [[cause]] of his {{Wiki|illness}}, [[Asanga]] replied, “I have a serious {{Wiki|disease}} of the [[heart]] which arose on account of you.” [[Vasubandu]] asked, “How did it arise on account of me?” [[Asanga]] replied, “Because you do not believe in the [[Mahayana]] and are forever attacking and criticizing it. For this wickedness you will be [[reborn]] in a [[miserable]] [[existence]]. Grieving for you has brought me close to [[death]].” [[Vasubandu]] was surprised at this and asked [[Asanga]] to expound the [[Mahayana]] to him. Upon doing so he became convinced of the [[truth]] of the [[Mahayana]] and asked his brother what he could do to overcome the negative [[karma]] he had accumulated. [[Asanga]] answered, “Since your [[skillful]] and eloquent [[speech]] against the [[Mahayana]] earned you this negative [[karma]], you must now use your [[skillful]] and eloquent [[speech]] to propound the [[Mahayana]].” |

[[Vasubandu]] went on to write many works which systematized the [[Consciousness Only]] teachings including On the [[Three Natures]], the Twenty Verses, and the Thirty Verses, perhaps the most famous of the [[Consciousness Only]] texts. He also wrote devotional hymns and commentaries on [[Mahayana texts]], including works of [[Asanga]]. He is also credited with [[being]] the founder of [[Pure Land]] [[Buddhism]]. | [[Vasubandu]] went on to write many works which systematized the [[Consciousness Only]] teachings including On the [[Three Natures]], the Twenty Verses, and the Thirty Verses, perhaps the most famous of the [[Consciousness Only]] texts. He also wrote devotional hymns and commentaries on [[Mahayana texts]], including works of [[Asanga]]. He is also credited with [[being]] the founder of [[Pure Land]] [[Buddhism]]. | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

According to one [[Tibetan]] account, | According to one [[Tibetan]] account, | ||

| − | [[Vasubandu]] was in the [[habit]] of reciting daily the [[Perfection]] of [[Wisdom]] in 8000 Verses. Once a year he would sit in an iron cauldron filled with sesame oil and for fifteen consecutive days and nights would recite five hundred [[Hinayana]] [[sutras]] and five hundred [[Mahayana sutras]]. After [[Asanga]] passed away, he became [[abbot]] of [[Nalanda]]. Every day he taught 20 classes on various [[Mahayana Sutras]] and constantly met in [[debate]] and defeated the false [[views]] of other [[teachers]]. For over 100 years he traveled in [[India]] and [[Nepal]] establishing the [[dharma]] and [[teaching]] the [[Mahayana]] [[doctrine]]. | + | [[Vasubandu]] was in the [[habit]] of reciting daily the [[Perfection]] of [[Wisdom]] in 8000 Verses. Once a year he would sit in an {{Wiki|iron}} cauldron filled with sesame oil and for fifteen consecutive days and nights would recite five hundred [[Hinayana]] [[sutras]] and five hundred [[Mahayana sutras]]. After [[Asanga]] passed away, he became [[abbot]] of [[Nalanda]]. Every day he [[taught]] 20 classes on various [[Mahayana Sutras]] and constantly met in [[debate]] and defeated the false [[views]] of other [[teachers]]. For over 100 years he traveled in [[India]] and [[Nepal]] establishing the [[dharma]] and [[teaching]] the [[Mahayana]] [[doctrine]]. |

[[File:Vasubandhu-00125.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Vasubandhu-00125.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

Many of his [[debates]] were with Samyka [[teachers]], a school like [[Yogacara]] based on [[yogic]] [[experience]] that flourished at that [[time]]. Other [[debates]] were with proponents of [[yoga]] as reflected in Patanjali’s famous [[sutras]]. | Many of his [[debates]] were with Samyka [[teachers]], a school like [[Yogacara]] based on [[yogic]] [[experience]] that flourished at that [[time]]. Other [[debates]] were with proponents of [[yoga]] as reflected in Patanjali’s famous [[sutras]]. | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

Stirmati | Stirmati | ||

| − | Stirmati was one of the famous [[disciples]] of [[Vasubandu]]. He was born in the southern [[Indian]] city of Dandakaranya of low [[caste]] parents, and studied with [[Vasubandu]] from age seven. He wrote commentaries on [[Abhidharma]] and the works of [[Vasubandu]], including the Trimsikabhasya (Commentary on The Thirty Verses). | + | Stirmati was one of the famous [[disciples]] of [[Vasubandu]]. He was born in the southern [[Indian]] city of Dandakaranya of low [[caste]] [[parents]], and studied with [[Vasubandu]] from age seven. He wrote commentaries on [[Abhidharma]] and the works of [[Vasubandu]], including the Trimsikabhasya (Commentary on The Thirty Verses). |

Dinaga | Dinaga | ||

| − | [[Dignaga]], another [[disciple]] of [[Vasubandu]], was one of the most respected [[Indian]] [[philosophers]]. Born in the southern [[Indian]] city of Simhavakta to a [[Brahmin]] family, he became a [[monk]] with a [[Hinayana]] [[teacher]], but dissatisfied with the [[Hinayana]] teachings went in search of further instruction and met [[Vasubandu]]. | + | [[Dignaga]], another [[disciple]] of [[Vasubandu]], was one of the most respected [[Indian]] [[philosophers]]. Born in the southern [[Indian]] city of [[Simhavakta]] to a [[Brahmin]] family, he became a [[monk]] with a [[Hinayana]] [[teacher]], but dissatisfied with the [[Hinayana]] teachings went in search of further instruction and met [[Vasubandu]]. |

Every day he would recite 500 [[Mahayana sutras]]. From a [[tantric]] [[master]] who was an [[emanation]] of [[Heruka]] he received the [[empowerment]] and the “Method of Actualization” of [[Manjushri]]. By practicing this, he received a [[vision]] of [[Manjushri]], and from then on received teachings from [[Manjushri]] whenever he wished. | Every day he would recite 500 [[Mahayana sutras]]. From a [[tantric]] [[master]] who was an [[emanation]] of [[Heruka]] he received the [[empowerment]] and the “Method of Actualization” of [[Manjushri]]. By practicing this, he received a [[vision]] of [[Manjushri]], and from then on received teachings from [[Manjushri]] whenever he wished. | ||

[[File:Dignaga-746o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dignaga-746o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Dignaga]] is known as the founder of [[Buddhist logic]]. He wrote over a hundred works on [[logic]] and other matters including [[Arya]] [[Prajnaparamita]] -samgraha-karika (A Verse Compendium of the [[Noble]] [[Perfection]] of [[Wisdom]]), and the [[Pramanasamuccaya]] (The Synthesis of All {{Wiki|Reasoning}}). The later was such a profound and timely text that according to the [[Tibetans]] when [[Dignaga]] wrote the salutation to the work, “Homage to him who is [[Logic]] personified…”, the [[earth]] shook, thunder and lightning flashed, and the legs of all the heretical [[teachers]] in the vicinity became as stiff as wood. Using his skills at [[logic]], he became famous as a debater. He was also famous for his [[miracles]] and had many [[disciples]]. He traveled throughout [[India]] establishing [[Mahayana]], and spent many years in [[Kashmir]]. He completed his [[life]] [[meditating]] in a remote {{Wiki|cave}} in the jungles of Odivisha. | + | [[Dignaga]] is known as the founder of [[Buddhist logic]]. He wrote over a hundred works on [[logic]] and other matters including [[Arya]] [[Prajnaparamita]] -samgraha-karika (A Verse Compendium of the [[Noble]] [[Perfection]] of [[Wisdom]]), and the [[Pramanasamuccaya]] (The Synthesis of All {{Wiki|Reasoning}}). The later was such a profound and timely text that according to the [[Tibetans]] when [[Dignaga]] wrote the salutation to the work, “Homage to him who is [[Logic]] personified…”, the [[earth]] shook, [[thunder]] and {{Wiki|lightning}} flashed, and the {{Wiki|legs}} of all the {{Wiki|heretical}} [[teachers]] in the vicinity became as stiff as [[wood]]. Using his skills at [[logic]], he became famous as a debater. He was also famous for his [[miracles]] and had many [[disciples]]. He traveled throughout [[India]] establishing [[Mahayana]], and spent many years in [[Kashmir]]. He completed his [[life]] [[meditating]] in a remote {{Wiki|cave}} in the jungles of Odivisha. |

[[Gunaprabha]] | [[Gunaprabha]] | ||

| − | [[Gunaprabha]], one of Vasubandu’s closest [[disciples]], is famous for his [[mastery]] of [[Vinaya]]. He was born in Mathura of a [[Brahmin]] family. He studied the {{Wiki|Vedic}} teachings, and the [[Hinayana]] teachings in addition to receiving [[Mahayana]] teachings from [[Vasubandu]]. | + | [[Gunaprabha]], one of Vasubandu’s closest [[disciples]], is famous for his [[mastery]] of [[Vinaya]]. He was born in [[Mathura]] of a [[Brahmin]] family. He studied the {{Wiki|Vedic}} teachings, and the [[Hinayana]] teachings in addition to receiving [[Mahayana]] teachings from [[Vasubandu]]. |

| − | According to the [[Tibetan]] accounts, he recited the Hundred Thousand [[Vinayas]] daily and resided in a [[monastery]] in Mathura called Adrapuri that had 5000 [[monks]], all of whom kept the [[Vinaya]] rules perfectly. | + | According to the [[Tibetan]] accounts, he recited the Hundred Thousand [[Vinayas]] daily and resided in a [[monastery]] in [[Mathura]] called Adrapuri that had 5000 [[monks]], all of whom kept the [[Vinaya]] rules perfectly. |

| − | He composed the Vinaya-Sutra, Basic Teachings of the [[Vinaya]] and One Hundred [[Actions]]. His Aphorisms of [[Discipline]] are one of the “five great [[books]]” that [[form]] the basis for the twenty year study program in [[Tibetan]] [[monastic]] colleges. | + | He composed the [[Vinaya-Sutra]], Basic Teachings of the [[Vinaya]] and One Hundred [[Actions]]. His {{Wiki|Aphorisms}} of [[Discipline]] are one of the “five great [[books]]” that [[form]] the basis for the twenty year study program in [[Tibetan]] [[monastic]] {{Wiki|colleges}}. |

[[File:Gunanrabkha-746867.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Gunanrabkha-746867.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Vimuktasena | + | [[Vimuktasena]] |

| − | Vimuktasena was another close [[disciple]] of [[Vasubandu]]. He is famous for his [[mastery]] of the Prajna-Paramita [[sutras]]. He was born in Jvala-guha in south-central [[India]]. He was a devotee of [[Maitreya]] and received both advice and teachings from the [[celestial]] [[Buddha]]. | + | [[Vimuktasena]] was another close [[disciple]] of [[Vasubandu]]. He is famous for his [[mastery]] of the [[Prajna-Paramita]] [[sutras]]. He was born in Jvala-guha in south-central [[India]]. He was a [[devotee]] of [[Maitreya]] and received both advice and teachings from the [[celestial]] [[Buddha]]. |

| − | He wrote a text called Twenty Thousand Lights on the Prajna-Paramitas. Towards the end of his [[life]] he became the [[spiritual]] guide of a [[king]] in {{Wiki|South India}} and supervised twenty-four [[temples]] where he widely taught the Prajna-Paramita [[Sutras]]. | + | He wrote a text called Twenty Thousand Lights on the Prajna-Paramitas. Towards the end of his [[life]] he became the [[spiritual]] [[guide]] of a [[king]] in {{Wiki|South India}} and supervised twenty-four [[temples]] where he widely [[taught]] the [[Prajna-Paramita]] [[Sutras]]. |

[[Dharmapala]] | [[Dharmapala]] | ||

| − | A [[disciple]] of Dinaga, [[Dharmapala]] became the head of [[Nalanda]] after his [[teacher]] [[died]]. After that he went to [[Bodhgaya]] and became [[abbot]] of the Mahabodhi [[Monastery]]. He [[died]] at the age of 32. He wrote a number of original works and commentaries most of which have been lost. | + | A [[disciple]] of Dinaga, [[Dharmapala]] became the head of [[Nalanda]] after his [[teacher]] [[died]]. After that he went to [[Bodhgaya]] and became [[abbot]] of the [[Mahabodhi]] [[Monastery]]. He [[died]] at the age of 32. He wrote a number of original works and commentaries most of which have been lost. |

[[Dharmakirti]] | [[Dharmakirti]] | ||

| − | [[Dharmakirti]] was born in the southern [[Indian]] town of Cudamani to a [[Brahmin]] family. At an early age he became learned in the arts, the teachings of the [[vedas]], [[medicine]], [[grammar]], and the tenets of the various sages. Then becoming inspired by the teachings of [[Buddha]] and the [[lineage]] of [[Pure Consciousness]], he took [[ordination]] as a [[monk]] from Ararya Dharmpala and studied the [[Tripitaka]] from beginning to end. Every day he recited 500 different [[sutras]] and [[mantras]]. | + | [[Dharmakirti]] was born in the southern [[Indian]] town of Cudamani to a [[Brahmin]] family. At an early age he became learned in the [[arts]], the teachings of the [[vedas]], [[medicine]], [[grammar]], and the {{Wiki|tenets}} of the various [[sages]]. Then becoming inspired by the teachings of [[Buddha]] and the [[lineage]] of [[Pure Consciousness]], he took [[ordination]] as a [[monk]] from Ararya Dharmpala and studied the [[Tripitaka]] from beginning to end. Every day he recited 500 different [[sutras]] and [[mantras]]. |

[[File:Dharmakirti47.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dharmakirti47.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | He became a great adept at [[logic]], equal to the [[master]] [[Dignaga]] himself, and wrote a famous commentary on Dignaga’s Synthesis of All {{Wiki|Reasoning}}. He also wrote Seven Treatises of [[Logic]]. His works became the basis for [[debate]] training in the [[Tibetan]] [[monasteries]]. He himself was said to be such an excellent debater that the population of [[Indian]] sages of other schools was quite depleted by his efforts, since after losing they had to convert to [[Buddhism]] or throw themselves into the [[Ganges]]. | + | He became a great {{Wiki|adept}} at [[logic]], {{Wiki|equal}} to the [[master]] [[Dignaga]] himself, and wrote a famous commentary on [[Dignaga’s]] Synthesis of All {{Wiki|Reasoning}}. He also wrote [[Seven Treatises]] of [[Logic]]. His works became the basis for [[debate]] training in the [[Tibetan]] [[monasteries]]. He himself was said to be such an {{Wiki|excellent}} debater that the population of [[Indian]] [[sages]] of other schools was quite depleted by his efforts, since after losing they had to convert to [[Buddhism]] or throw themselves into the [[Ganges]]. |

| − | Silabhadra | + | [[Silabhadra]] |

| − | A [[disciple]] of [[Dharmapala]], Silabhadra was born to a royal [[Brahmin]] family in the East [[Indian]] city of Samatata. He was conversant with the teachings of all sects, famous for his [[mastery]] of [[Buddhist sutras]] and commentaries, and became head of [[Nalanda]] where 104 years old, he taught the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Master]], Hsuan-Tsang, the [[Consciousness Only]] [[doctrine]] through his exposition of Asanga’s Treatise on the Stages of [[Yoga]] Practice. | + | A [[disciple]] of [[Dharmapala]], [[Silabhadra]] was born to a {{Wiki|royal}} [[Brahmin]] family in the [[East]] [[Indian]] city of {{Wiki|Samatata}}. He was conversant with the teachings of all sects, famous for his [[mastery]] of [[Buddhist sutras]] and commentaries, and became head of [[Nalanda]] where 104 years old, he [[taught]] the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Master]], [[Hsuan-Tsang]], the [[Consciousness Only]] [[doctrine]] through his [[exposition]] of [[Asanga’s]] Treatise on the Stages of [[Yoga]] Practice. |

[[Paramartha]] | [[Paramartha]] | ||

| − | [[Paramartha]] was one of the great translators of [[Buddhist texts]] into {{Wiki|Chinese}}, [[Paramartha]] was already a [[master]] in [[India]] when he traveled to [[China]] in 546 at the age of 47. At the request of the emperor of [[China]], he settled in the capital and began the translation of texts. {{Wiki|Political}} instability in [[China]] forced him to move quite often, but he was still able to translate the important works of the [[Yogacara]] [[lineage]] into {{Wiki|Chinese}} including the [[Abhidharmakosa]], the Mahayana-Samparigraha, and various works of [[Vasubandu]]. He is also famous for his translation of the [[Diamond Sutra]]. All together, [[Paramartha]] translated sixty-four works in 278 volumes. His translations made the later success of [[Yogacara]] possible in [[China]] and inspired Hsuan-Tsang several generations later to travel to [[India]] for additional texts and commentaries. | + | [[Paramartha]] was one of the great [[translators]] of [[Buddhist texts]] into {{Wiki|Chinese}}, [[Paramartha]] was already a [[master]] in [[India]] when he traveled to [[China]] in 546 at the age of 47. At the request of the [[emperor]] of [[China]], he settled in the capital and began the translation of texts. {{Wiki|Political}} instability in [[China]] forced him to move quite often, but he was still able to translate the important works of the [[Yogacara]] [[lineage]] into {{Wiki|Chinese}} including the [[Abhidharmakosa]], the Mahayana-Samparigraha, and various works of [[Vasubandu]]. He is also famous for his translation of the [[Diamond Sutra]]. All together, [[Paramartha]] translated sixty-four works in 278 volumes. His translations made the later [[success]] of [[Yogacara]] possible in [[China]] and inspired [[Hsuan-Tsang]] several generations later to travel to [[India]] for additional texts and commentaries. |

| − | Hsuan-Tsang | + | [[Hsuan-Tsang]] |

| − | Hsuan-Tsang was a remarkable [[spiritual]] [[pilgrim]] who became one of the most famous {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Masters]]. The son of a poor {{Wiki|Chinese}} official, he left home at the age of 13 to study [[Buddhism]]. According to a [[traditional]] account, | + | [[Hsuan-Tsang]] was a remarkable [[spiritual]] [[pilgrim]] who became one of the most famous {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Masters]]. The son of a poor {{Wiki|Chinese}} official, he left home at the age of 13 to study [[Buddhism]]. According to a [[traditional]] account, |

| − | During those early years of study, if there was a [[Dharma]] [[Master]] lecturing on a [[Buddhist text]], no matter who the [[Dharma]] [[Master]] was or how far away the lecture was [[being]] held, he went, whether it was a [[Sutra]] lecture, a [[Shastra]] lecture or a [[Vinaya]] lecture. He listened to them all. Wind and rain couldn’t keep him away from lectures on the [[Tripitaka]], to the point that he even forgot to be hungry. He just took the [[Buddhadharma]] as his [[food]] and drink. He did this for five years and then took the Complete [[Precepts]]. | + | During those early years of study, if there was a [[Dharma]] [[Master]] lecturing on a [[Buddhist text]], no {{Wiki|matter}} who the [[Dharma]] [[Master]] was or how far away the lecture was [[being]] held, he went, whether it was a [[Sutra]] lecture, a [[Shastra]] lecture or a [[Vinaya]] lecture. He listened to them all. [[Wind]] and [[rain]] couldn’t keep him away from lectures on the [[Tripitaka]], to the point that he even forgot to be hungry. He just took the [[Buddhadharma]] as his [[food]] and drink. He did this for five years and then took the Complete [[Precepts]]. |

| − | In 629 at the age of 27, having been a [[monk]] for fifteen years, he secretly left [[China]] and made the [[dangerous]] journey across the silk road to [[India]]. Sixteen years later, having learned [[Sanskrit]] and studied with the best [[Indian]] [[teachers]], he returned with an incredible collection of 657 [[Indian]] texts, a number of [[statues]] of the [[Buddha]] and various [[relics]]. He was acclaimed by the [[Emperor]] who supported him the remainder of his [[life]] so he could translate the texts and convey the [[Mahayana]] teachings to [[China]]. On his deathbed he dedicated his [[merit]] so that all present would be born again among the inner circle of [[Maitreya]] in [[Tushita Heaven]] | + | In 629 at the age of 27, having been a [[monk]] for fifteen years, he secretly left [[China]] and made the [[dangerous]] journey across the [[silk road]] to [[India]]. Sixteen years later, having learned [[Sanskrit]] and studied with the best [[Indian]] [[teachers]], he returned with an incredible collection of 657 [[Indian]] texts, a number of [[statues]] of the [[Buddha]] and various [[relics]]. He was acclaimed by the [[Emperor]] who supported him the remainder of his [[life]] so he could translate the texts and convey the [[Mahayana]] teachings to [[China]]. On his deathbed he dedicated his [[merit]] so that all {{Wiki|present}} would be born again among the inner circle of [[Maitreya]] in [[Tushita Heaven]] |

| − | Kuei-Chi (638-682 A.D.) was Hsuan-Tsang’s most prominent {{Wiki|Chinese}} student. He systematized the [[Yogacara]] [[teaching]] and established [[Yogacara]] as a distinct school in [[China]], called [[Fa-hsiang]]. He also wrote commentaries to Hsuan-Tsang’s [[Yogacara]] works including the Fa-yuan-i-lin-chang and the Wei-shih-shu-chi. | + | Kuei-Chi (638-682 A.D.) was Hsuan-Tsang’s most prominent {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[student]]. He systematized the [[Yogacara]] [[teaching]] and established [[Yogacara]] as a {{Wiki|distinct}} school in [[China]], called [[Fa-hsiang]]. He also wrote commentaries to Hsuan-Tsang’s [[Yogacara]] works including the Fa-yuan-i-lin-chang and the Wei-shih-shu-chi. |

| − | Hsuan-Tsang also had several notable {{Wiki|Japanese}} and [[Korean]] students. [[Dosho]] (628-700) studied with Hsuan-Tsang for ten years sharing a room with Kuei-Chi. When he left to go back to [[Japan]] he was given [[sutras]], treatises and [[Yogacara]] commentaries to help him establish [[Yogacara]] there which he did, [[teaching]] at Bwangoji [[monastery]]. His most famous student is Gyogi (667-748). A [[Korean]] student [[Chiho]] studied with Hsuan-Tsang and also went to [[Japan]] to teach. His pupil [[Gembo]] went back to [[China]] in 716 and was instructed by Chih-Chou, a pupil of Kuei-Chi. Another early {{Wiki|Japanese}} student who studied with Hsuan-Tsang was [[Chitsu]]. “[[Thus]],” as Junjiro Takakusu wrote in his [[Essentials]] of [[Buddhist Philosophy]] in 1947, “[[Japan]] received the {{Wiki|orthodox}} [[teaching]] sacrosanct from first-hand authorities of the [[Indian]] and {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Yogacara]] School and with the {{Wiki|Japanese}} even now it is the chief [[subject]] of [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|learning}}.” | + | [[Hsuan-Tsang]] also had several notable {{Wiki|Japanese}} and [[Korean]] students. [[Dosho]] (628-700) studied with [[Hsuan-Tsang]] for ten years sharing a room with Kuei-Chi. When he left to go back to [[Japan]] he was given [[sutras]], treatises and [[Yogacara]] commentaries to help him establish [[Yogacara]] there which he did, [[teaching]] at Bwangoji [[monastery]]. His most famous [[student]] is Gyogi (667-748). A [[Korean]] [[student]] [[Chiho]] studied with [[Hsuan-Tsang]] and also went to [[Japan]] to teach. His pupil [[Gembo]] went back to [[China]] in 716 and was instructed by Chih-Chou, a pupil of Kuei-Chi. Another early {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[student]] who studied with [[Hsuan-Tsang]] was [[Chitsu]]. “[[Thus]],” as Junjiro [[Takakusu]] wrote in his [[Essentials]] of [[Buddhist Philosophy]] in 1947, “[[Japan]] received the {{Wiki|orthodox}} [[teaching]] sacrosanct from first-hand authorities of the [[Indian]] and {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Yogacara]] School and with the {{Wiki|Japanese}} even now it is the chief [[subject]] of [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|learning}}.” |

| − | [[Hosso]], the {{Wiki|Japanese}} name for [[Yogacara]], thrived during the {{Wiki|Nara period}} and today several prominent ancient [[temples]] are still functioning. [[Yogacara]] proper in [[India]] and [[China]] did not fare so well. The [[Yogacara]] School in [[India]] became part of a Yogacara-Madhyamika School which thrived in the last centuries before [[Buddhism]] disappeared in [[India]] under Islamic persecution. This school became influential in [[Tibet]] through [[Santaraksita]], one of the first [[Buddhist Masters]] to teach in [[Tibet]], and today all [[Tibetan]] sects have a strong [[Yogacara]] component. This is especially [[visible]] in the more contemplative [[Kagyu]] and [[Nyingma]] practice [[traditions]]. Several [[Kagyu]] [[teachers]] have supervised English translations of Asanga’s works in recent years. | + | [[Hosso]], the {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[name]] for [[Yogacara]], thrived during the {{Wiki|Nara period}} and today several prominent {{Wiki|ancient}} [[temples]] are still functioning. [[Yogacara]] proper in [[India]] and [[China]] did not fare so well. The [[Yogacara]] School in [[India]] became part of a Yogacara-Madhyamika School which thrived in the last centuries before [[Buddhism]] disappeared in [[India]] under {{Wiki|Islamic}} persecution. This school became influential in [[Tibet]] through [[Santaraksita]], one of the first [[Buddhist Masters]] to teach in [[Tibet]], and today all [[Tibetan]] sects have a strong [[Yogacara]] component. This is especially [[visible]] in the more {{Wiki|contemplative}} [[Kagyu]] and [[Nyingma]] practice [[traditions]]. Several [[Kagyu]] [[teachers]] have supervised English translations of [[Asanga’s]] works in recent years. |

An example of the [[respect]] [[Tibetan]] [[teachers]] have for [[Yogacara]] is this [[appreciation]] taken from a [[dharma talk]] by the [[Venerable]] [[Traleg Rinpoche]], | An example of the [[respect]] [[Tibetan]] [[teachers]] have for [[Yogacara]] is this [[appreciation]] taken from a [[dharma talk]] by the [[Venerable]] [[Traleg Rinpoche]], | ||

| − | [[People]] have generally ignored how [[Yogacara]] [[philosophy]] influenced [[Buddhist]] [[tantra]] and its development. Even though it’s quite patent in the writings of [[Buddhist]] [[tantra]]… [[Yogacara]] [[philosophy]] itself developed as a reaction against too much theorization. It came to emphasize {{Wiki|individual}} [[experience]] and practice,hence the name [[Yogacara]], meaning practitioners of [[yoga]]… You could not theorize about [[Yogacara]] [[philosophy]] without [[meditating]]. In fact, you could not be a [[Yogacara]] [[philosopher]] unless you [[meditate]]. When we look at the writings of [[Yogacara]] [[philosophy]], we discover many [[tantric]] concepts mentioned. | + | [[People]] have generally ignored how [[Yogacara]] [[philosophy]] influenced [[Buddhist]] [[tantra]] and its [[development]]. Even though it’s quite patent in the writings of [[Buddhist]] [[tantra]]… [[Yogacara]] [[philosophy]] itself developed as a {{Wiki|reaction}} against too much theorization. It came to {{Wiki|emphasize}} {{Wiki|individual}} [[experience]] and practice,hence the [[name]] [[Yogacara]], meaning practitioners of [[yoga]]… You could not theorize about [[Yogacara]] [[philosophy]] without [[meditating]]. In fact, you could not be a [[Yogacara]] [[philosopher]] unless you [[meditate]]. When we look at the writings of [[Yogacara]] [[philosophy]], we discover many [[tantric]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] mentioned. |

| − | The [[Fa-hsiang]] School [[suffered]] under the general persecution of [[Buddhism]] in [[China]] during the middle of the 9th century and gradually disappeared. However, its works are still preserved, and it was revived in the 20th century by several [[Masters]] including Ou-Yang Ching-Wu (1871-1943), [[Abbot]] Taiuhso (1889-1947, and Hsin Shih-Li (1883-1968), who wrote A New [[Doctrine]] of [[Consciousness Only]] in 1944. This revival led to the Hsuan-Tsang’s Cheng Wei Shih Lun [[being]] translated into English for the first [[time]] in 1973 by Wei Tat, a member of a {{Wiki|Hong Kong}} [[Yogacara]] group. | + | The [[Fa-hsiang]] School [[suffered]] under the general persecution of [[Buddhism]] in [[China]] during the middle of the 9th century and gradually disappeared. However, its works are still preserved, and it was revived in the 20th century by several [[Masters]] including [[Ou-Yang]] Ching-Wu (1871-1943), [[Abbot]] Taiuhso (1889-1947, and Hsin Shih-Li (1883-1968), who wrote A New [[Doctrine]] of [[Consciousness Only]] in 1944. This revival led to the Hsuan-Tsang’s Cheng Wei Shih Lun [[being]] translated into English for the first [[time]] in 1973 by Wei Tat, a member of a {{Wiki|Hong Kong}} [[Yogacara]] group. |

| − | Perhaps the greatest success of the [[Yogacara]] teachings was in [[Gandhara]] where it Third Turning was revealed. There [[Yogacara]] became the foundation for [[Dzogchen]] which flourishes today in [[Tibet]] as the summit of [[Buddhist philosophy]]. That is no small {{Wiki|honor}} for the remarkable work the early [[Yogacara]] [[Masters]] accomplished in clarifying the [[essence]] of the [[Mahayana]] [[path]]. | + | Perhaps the greatest [[success]] of the [[Yogacara]] teachings was in [[Gandhara]] where it Third Turning was revealed. There [[Yogacara]] became the foundation for [[Dzogchen]] which flourishes today in [[Tibet]] as the summit of [[Buddhist philosophy]]. That is no small {{Wiki|honor}} for the remarkable work the early [[Yogacara]] [[Masters]] accomplished in clarifying the [[essence]] of the [[Mahayana]] [[path]]. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://wutai.wordpress.com/category/yogacara/ wutai.wordpress.com] | [http://wutai.wordpress.com/category/yogacara/ wutai.wordpress.com] | ||

[[Category:Yogacara]] | [[Category:Yogacara]] | ||

Revision as of 18:39, 10 July 2014

The wisdom teachings of the Mahayana are contained in three primary sets of writings. The first and oldest of these are the Prajnaparamita texts, which date to the beginning of the current era. These wisdom texts go beyond conventional understanding and speak directly to one’s innate enlightened nature. They are the first pointing out texts –transmitting the transcendent wisdom that sees the emptiness of all conceptualized views of reality.

Later, Nargarjuna applied the insights of the Prajnaparamita to classical Indian philosophy and through his articulation of the nature of emptiness beautifully and impeccably dismantled prevailing scholastic views on the nature of reality, establishing the primacy of the inexpressible as the heart of the Buddhist path. In the Mahayana tradition Nargarjuna is seen as the primary spokesperson of the Pranjaparamita literature.

These teachings were united with the meditative and devotional traditions of Mahayana by a brilliant set of teachers from Gandhara, Asanga and Vasubandu, whose works are the culmination of the early Mahayana movement. The school that held this transmission tradition was Yogacara, which became the leading philosophical school in India during the 3rd to 5th centuries, at the same time that Neoplatonism was the leading philosophical school in the Classical Western World. Yogacara teachings still form the philosophical core of the great Buddhist contemplative lineages such as Zen, Mahamudra and Dzogchen. In a similar manner Neoplatonism underlines Western contemplative lineages.

Yogacara translates as “practitioners of yoga” emphasizing the school’s commitment to meditation as the essential nature of the Buddhist path. It is also known as the Consciousness Only School for their central teaching that all reality is a display of consciousness.

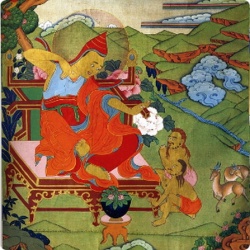

Asanga

According to the Tibetan tradition, Asanga was born in Purusapura, the capital of Gandhara, of a Brahmin woman who was herself a considerable adept in the teachings of Buddhism and who taught him the “eighteen sciences” which he mastered easily. He became a monk and for five years applied himself diligently, memorizing one hundred thousand verses of dharma each year and correctly understanding their meaning.

He then left the monastery to practice the Arya Maitreya Sadhana in a cave at the foot of a mountain. For three years, not a single good sign appeared, and he became depressed and decided to leave his retreat. Emerging from his cave he noticed a bird’s nest by the mountain where the rock had become worn just by the brushing of the bird’s wing as it flew back and forth. Realizing his perseverance was weak, he returned to his cave to practice. For three more years he meditated, but again not a single good sign appeared. He became discouraged and left again. This time he saw a rock beside the road that was slowly disintegrating because of the trickle of single drops of water. Inspired by this, he returned and practiced another three years.

When again no signs appeared, he left his retreat a third time. He encountered an old man who was rubbing a piece of iron with a smooth cotton cloth. “I am just finishing this needle,” the man said to Asanga. “I have already made those over there” and pointed to small pile of needles lying nearby. Asanga thought, “If such effort is put into a mundane task such as this, my effort so far has been merely a trifle.”

He returned and meditated for another three years. Although he had by now meditated for 12 years on Maitreya, he still had no signs of favor. He became extremely despondent and walked away from his cave. After awhile he came across a half-dead dog lying beside the road, infested with maggots, crying out in pain. Asanga thought, “This dog will die if these worms are not removed, but if I try to lift them out with my hand, I will crush them.” So using his tongue so as not to hurt them, and cutting off some of his own flesh for them to live in, he bent down to remove them. At that moment the dog vanished and Maitreya appeared, showering cascades of light in all directions.

Asanga burst into tears and cried, “Ah, my sole teacher and refuge, all those years I made so much effort in my practice, exerting myself in a hundred different ways, but I saw nothing. Why has the rain and the might of the ocean come only now when tormented by pain, I am no longer thirsting?” Maitreya replied, “In truth, I was in your presence constantly, yet because of karmic obscuration you were unable to see me. However, your practice has purified your karma and removed your obstacles. Now by the force of your great compassion you are able to meet me. To test my words, put me on you shoulders for others to see and carry me across the city.”

Asanga was overjoyed. Lifting Maitreya onto his shoulders carried him into town, yet no one saw Maitreya. One old woman saw Asanga was carrying a dead dog and that brought her endless good fortune. A faithful servant saw Maitreya’s feet and found himself in a state of samadhi which granted him all the siddhis. Asanga himself realized the samadhi called “Continuum of Reality”. “What is your desire now?” Maitreya asked him. “To revive the teachings of the Mahayana,” Asanga replied. “Well then, hold onto the end of my robe.” Asanga did this and together they ascended to the pure land of Tushita where they stayed for fifty years. Here Asanga mastered the teachings of the Mahayana and received the famous Five Texts of Maitreya, each of which opens a different door of samadhi.

Dedicated to actualizing these teachings, Asanga returned to the earth and built a small temple in a forest. At first only a few students came to learn teachings from him, but gradually the fame of his doctrine spread and the Yogacara School was established. He became the abbot of Nalanda and lived to be well over 100, but always had a youthful look, with no gray hair or wrinkles.

He compiled many important Mahayana works including what has come to be known as The Five Texts of Maitreya. These include the Abhisamayalamkara (Ornament of Clear Comprehension), the Mahanaya Sutralankara (Ornament of the Mahayana Sutras), the Madhyanta-vibhanga (Discourse on the Middle between the Extremes), the Dharma-dharmata-vibhaga, and the Uttaratantra (The Peerless Continuum). His Mahayana-samparigraha (Compendium of the Mahayana), Abhidarma-samuccaya (Compendium of Higher Doctrine), and Yogacharabhumi-shastra (Treatise on the Stages of Yoga Practice) are also famous.

According to the Tibetan historian Taranatha, Tantric teachings were handed down in secret through the Yogacara lineage from the time of Asanga. In the Tibetan canon are several Tantric works ascribed to Asanga including a Maitreya Sadhana and a Prajna-Paramita Sadhana.

Vasubandu

The cofounder of Yogacara, Vasubandu, is traditionally said to be the younger brother of Asanga. He was also born in Purusapura in Gandhara and became a monk of the Sarvastivadin school. He went to Kashmir to study their teachings including their renown Abhidharma works. He also was said to possess a complete understanding of the Tripitaka and the tenets of all the Hinayana schools.

Vasubandu wrote Seven Branches of Metaphysics, an encyclopedic work clarifying the main points of teachings of the early Arhats, The Four Oral Traditions of Vinaya on Buddhist discipline, and the most famous compendium of Abhidharma teachings in the Buddhist tradition, the Abhidharma-kosa and a commentary to it called the Abhidharma-kosa-Bhayasa. The Kosa describes the Buddhist path to enlightenment by categorizing and analyzing the basic factors of experience called dharmas.

Already famous for his intellectual understanding of Buddhism, Vasubandu came to Nalanda University and was converted to the Mahayana by Asanga. According to a traditional account, Asanga summoned Vasubandu under the pretext that he was dying. When Vasubandu arrived and asked the cause of his illness, Asanga replied, “I have a serious disease of the heart which arose on account of you.” Vasubandu asked, “How did it arise on account of me?” Asanga replied, “Because you do not believe in the Mahayana and are forever attacking and criticizing it. For this wickedness you will be reborn in a miserable existence. Grieving for you has brought me close to death.” Vasubandu was surprised at this and asked Asanga to expound the Mahayana to him. Upon doing so he became convinced of the truth of the Mahayana and asked his brother what he could do to overcome the negative karma he had accumulated. Asanga answered, “Since your skillful and eloquent speech against the Mahayana earned you this negative karma, you must now use your skillful and eloquent speech to propound the Mahayana.”

Vasubandu went on to write many works which systematized the Consciousness Only teachings including On the Three Natures, the Twenty Verses, and the Thirty Verses, perhaps the most famous of the Consciousness Only texts. He also wrote devotional hymns and commentaries on Mahayana texts, including works of Asanga. He is also credited with being the founder of Pure Land Buddhism.

According to one Tibetan account,

Vasubandu was in the habit of reciting daily the Perfection of Wisdom in 8000 Verses. Once a year he would sit in an iron cauldron filled with sesame oil and for fifteen consecutive days and nights would recite five hundred Hinayana sutras and five hundred Mahayana sutras. After Asanga passed away, he became abbot of Nalanda. Every day he taught 20 classes on various Mahayana Sutras and constantly met in debate and defeated the false views of other teachers. For over 100 years he traveled in India and Nepal establishing the dharma and teaching the Mahayana doctrine.

Many of his debates were with Samyka teachers, a school like Yogacara based on yogic experience that flourished at that time. Other debates were with proponents of yoga as reflected in Patanjali’s famous sutras.

After a long life, Vasubandu eventually left this world to reside in the Tushita heaven with Maitreya.

Stirmati

Stirmati was one of the famous disciples of Vasubandu. He was born in the southern Indian city of Dandakaranya of low caste parents, and studied with Vasubandu from age seven. He wrote commentaries on Abhidharma and the works of Vasubandu, including the Trimsikabhasya (Commentary on The Thirty Verses).

Dinaga

Dignaga, another disciple of Vasubandu, was one of the most respected Indian philosophers. Born in the southern Indian city of Simhavakta to a Brahmin family, he became a monk with a Hinayana teacher, but dissatisfied with the Hinayana teachings went in search of further instruction and met Vasubandu.

Every day he would recite 500 Mahayana sutras. From a tantric master who was an emanation of Heruka he received the empowerment and the “Method of Actualization” of Manjushri. By practicing this, he received a vision of Manjushri, and from then on received teachings from Manjushri whenever he wished.

Dignaga is known as the founder of Buddhist logic. He wrote over a hundred works on logic and other matters including Arya Prajnaparamita -samgraha-karika (A Verse Compendium of the Noble Perfection of Wisdom), and the Pramanasamuccaya (The Synthesis of All Reasoning). The later was such a profound and timely text that according to the Tibetans when Dignaga wrote the salutation to the work, “Homage to him who is Logic personified…”, the earth shook, thunder and lightning flashed, and the legs of all the heretical teachers in the vicinity became as stiff as wood. Using his skills at logic, he became famous as a debater. He was also famous for his miracles and had many disciples. He traveled throughout India establishing Mahayana, and spent many years in Kashmir. He completed his life meditating in a remote cave in the jungles of Odivisha.

Gunaprabha

Gunaprabha, one of Vasubandu’s closest disciples, is famous for his mastery of Vinaya. He was born in Mathura of a Brahmin family. He studied the Vedic teachings, and the Hinayana teachings in addition to receiving Mahayana teachings from Vasubandu.

According to the Tibetan accounts, he recited the Hundred Thousand Vinayas daily and resided in a monastery in Mathura called Adrapuri that had 5000 monks, all of whom kept the Vinaya rules perfectly.

He composed the Vinaya-Sutra, Basic Teachings of the Vinaya and One Hundred Actions. His Aphorisms of Discipline are one of the “five great books” that form the basis for the twenty year study program in Tibetan monastic colleges.

Vimuktasena

Vimuktasena was another close disciple of Vasubandu. He is famous for his mastery of the Prajna-Paramita sutras. He was born in Jvala-guha in south-central India. He was a devotee of Maitreya and received both advice and teachings from the celestial Buddha.

He wrote a text called Twenty Thousand Lights on the Prajna-Paramitas. Towards the end of his life he became the spiritual guide of a king in South India and supervised twenty-four temples where he widely taught the Prajna-Paramita Sutras.

Dharmapala

A disciple of Dinaga, Dharmapala became the head of Nalanda after his teacher died. After that he went to Bodhgaya and became abbot of the Mahabodhi Monastery. He died at the age of 32. He wrote a number of original works and commentaries most of which have been lost.

Dharmakirti

Dharmakirti was born in the southern Indian town of Cudamani to a Brahmin family. At an early age he became learned in the arts, the teachings of the vedas, medicine, grammar, and the tenets of the various sages. Then becoming inspired by the teachings of Buddha and the lineage of Pure Consciousness, he took ordination as a monk from Ararya Dharmpala and studied the Tripitaka from beginning to end. Every day he recited 500 different sutras and mantras.

He became a great adept at logic, equal to the master Dignaga himself, and wrote a famous commentary on Dignaga’s Synthesis of All Reasoning. He also wrote Seven Treatises of Logic. His works became the basis for debate training in the Tibetan monasteries. He himself was said to be such an excellent debater that the population of Indian sages of other schools was quite depleted by his efforts, since after losing they had to convert to Buddhism or throw themselves into the Ganges.

Silabhadra

A disciple of Dharmapala, Silabhadra was born to a royal Brahmin family in the East Indian city of Samatata. He was conversant with the teachings of all sects, famous for his mastery of Buddhist sutras and commentaries, and became head of Nalanda where 104 years old, he taught the Chinese Master, Hsuan-Tsang, the Consciousness Only doctrine through his exposition of Asanga’s Treatise on the Stages of Yoga Practice.

Paramartha

Paramartha was one of the great translators of Buddhist texts into Chinese, Paramartha was already a master in India when he traveled to China in 546 at the age of 47. At the request of the emperor of China, he settled in the capital and began the translation of texts. Political instability in China forced him to move quite often, but he was still able to translate the important works of the Yogacara lineage into Chinese including the Abhidharmakosa, the Mahayana-Samparigraha, and various works of Vasubandu. He is also famous for his translation of the Diamond Sutra. All together, Paramartha translated sixty-four works in 278 volumes. His translations made the later success of Yogacara possible in China and inspired Hsuan-Tsang several generations later to travel to India for additional texts and commentaries.

Hsuan-Tsang

Hsuan-Tsang was a remarkable spiritual pilgrim who became one of the most famous Chinese Masters. The son of a poor Chinese official, he left home at the age of 13 to study Buddhism. According to a traditional account,

During those early years of study, if there was a Dharma Master lecturing on a Buddhist text, no matter who the Dharma Master was or how far away the lecture was being held, he went, whether it was a Sutra lecture, a Shastra lecture or a Vinaya lecture. He listened to them all. Wind and rain couldn’t keep him away from lectures on the Tripitaka, to the point that he even forgot to be hungry. He just took the Buddhadharma as his food and drink. He did this for five years and then took the Complete Precepts.

In 629 at the age of 27, having been a monk for fifteen years, he secretly left China and made the dangerous journey across the silk road to India. Sixteen years later, having learned Sanskrit and studied with the best Indian teachers, he returned with an incredible collection of 657 Indian texts, a number of statues of the Buddha and various relics. He was acclaimed by the Emperor who supported him the remainder of his life so he could translate the texts and convey the Mahayana teachings to China. On his deathbed he dedicated his merit so that all present would be born again among the inner circle of Maitreya in Tushita Heaven

Kuei-Chi (638-682 A.D.) was Hsuan-Tsang’s most prominent Chinese student. He systematized the Yogacara teaching and established Yogacara as a distinct school in China, called Fa-hsiang. He also wrote commentaries to Hsuan-Tsang’s Yogacara works including the Fa-yuan-i-lin-chang and the Wei-shih-shu-chi.

Hsuan-Tsang also had several notable Japanese and Korean students. Dosho (628-700) studied with Hsuan-Tsang for ten years sharing a room with Kuei-Chi. When he left to go back to Japan he was given sutras, treatises and Yogacara commentaries to help him establish Yogacara there which he did, teaching at Bwangoji monastery. His most famous student is Gyogi (667-748). A Korean student Chiho studied with Hsuan-Tsang and also went to Japan to teach. His pupil Gembo went back to China in 716 and was instructed by Chih-Chou, a pupil of Kuei-Chi. Another early Japanese student who studied with Hsuan-Tsang was Chitsu. “Thus,” as Junjiro Takakusu wrote in his Essentials of Buddhist Philosophy in 1947, “Japan received the orthodox teaching sacrosanct from first-hand authorities of the Indian and Chinese Yogacara School and with the Japanese even now it is the chief subject of Buddhist learning.”

Hosso, the Japanese name for Yogacara, thrived during the Nara period and today several prominent ancient temples are still functioning. Yogacara proper in India and China did not fare so well. The Yogacara School in India became part of a Yogacara-Madhyamika School which thrived in the last centuries before Buddhism disappeared in India under Islamic persecution. This school became influential in Tibet through Santaraksita, one of the first Buddhist Masters to teach in Tibet, and today all Tibetan sects have a strong Yogacara component. This is especially visible in the more contemplative Kagyu and Nyingma practice traditions. Several Kagyu teachers have supervised English translations of Asanga’s works in recent years.

An example of the respect Tibetan teachers have for Yogacara is this appreciation taken from a dharma talk by the Venerable Traleg Rinpoche,

People have generally ignored how Yogacara philosophy influenced Buddhist tantra and its development. Even though it’s quite patent in the writings of Buddhist tantra… Yogacara philosophy itself developed as a reaction against too much theorization. It came to emphasize individual experience and practice,hence the name Yogacara, meaning practitioners of yoga… You could not theorize about Yogacara philosophy without meditating. In fact, you could not be a Yogacara philosopher unless you meditate. When we look at the writings of Yogacara philosophy, we discover many tantric concepts mentioned.

The Fa-hsiang School suffered under the general persecution of Buddhism in China during the middle of the 9th century and gradually disappeared. However, its works are still preserved, and it was revived in the 20th century by several Masters including Ou-Yang Ching-Wu (1871-1943), Abbot Taiuhso (1889-1947, and Hsin Shih-Li (1883-1968), who wrote A New Doctrine of Consciousness Only in 1944. This revival led to the Hsuan-Tsang’s Cheng Wei Shih Lun being translated into English for the first time in 1973 by Wei Tat, a member of a Hong Kong Yogacara group.

Perhaps the greatest success of the Yogacara teachings was in Gandhara where it Third Turning was revealed. There Yogacara became the foundation for Dzogchen which flourishes today in Tibet as the summit of Buddhist philosophy. That is no small honor for the remarkable work the early Yogacara Masters accomplished in clarifying the essence of the Mahayana path.