Difference between revisions of "Accomplishment"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

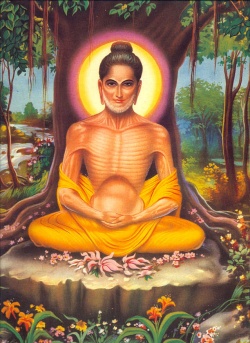

| − | [[File:Buddha12.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | + | [[File:Buddha12.jpg|thumb|250px|]]<nomobile>{{DisplayImages|3480|426|3255|1589|795|3104|1606}}</nomobile> |

Revision as of 06:38, 27 December 2015

Accomplishment. 1) (dngos grub, Skt. siddhi) (cheng-jiu): .

The attainment resulting from Dharma practice usually referring to the 'supreme accomplishment' of complete enlightenment.

It can also mean the 'common accomplishments,' eight mundane accomplishments such as:

clairvoyance,

clairaudiance,

flying in the sky,

becoming invisible,

everlasting youth, or

powers of transmutation.

The most eminent attainments on the path are, however,

renunciation,

compassion,

unshakable faith and

realization of the correct view.

See also 'supreme and common accomplishments.'

2) (sgrub pa). See 'four aspects of approach and accomplishment' and 'approach and accomplishment.'

Accomplishment (dngos grub)

- Spiritual accomplishments (Skt. siddhi) may be supramundane or common.

The former (mchog gi dngos grub) refers to the accomplishment of enlightenment or buddhahood, transcending cyclic existence.

The latter (thun mong gi dngos grub) are a series of mystical powers gained through meditative practices which are based on mantra recitation in the context of specific rituals.

Eight such types of common accomplishment are enumerated:

1) The accomplishment of compounding pills that can sustain life without conventional food for a long period (ril bu’i dngos grub);

2) The accomplishment of preparing an eye salve which can extend one's vision (mig sman gyi dngos grub);

3) The accomplishment of being able to walk underground without obstruction (sa ’og gi dngos grub);

4) The accomplishment of being able to ride on a flying sword (ral gri’i dngos grub);

5) The accomplishment of being able to fly (mkha’ la phur ba’i dngos grub);

6) The accomplishment of invisibility (mi snang ba’i dngos grub);

7) The accomplishment of being able to prolong one's life indefinitely (‘chi ba med pa’I dngos grub); and

8) The accomplishment of the power to heal diseases (nad ‘joms pa’I dngos grub).

The above accomplishments are mundane in that the purposes they fulfill are ordinary and such feats can be acquired without any experience of emptiness (śūnyatā) or enlightened mind (bodhicitta).

For references to these powers in rNying-ma literature, see e.g. NSTB, pp. 247, 281, 404, and 480. GD (from the Glossary to Tibetan Elemental Divination Paintings)

- 1) (dngos grub), Skt. siddhi. The attainment resulting from Dharma practice usually referring to the 'supreme accomplishment' of complete enlightenment.

It can also mean the 'common accomplishments,' eight mundane accomplishments such as:

clairvoyance,

clairaudiance,

flying in the sky,

becoming invisible,

everlasting youth, or powers of transmutation.

The most eminent attainments on the path are, however, renunciation, compassion, unshakable faith and realization of the correct view.

See also 'supreme and common accomplishments.'

Source

RangjungYesheWiki:Accomplishment

2) (sgrub pa). See also 'approach and accomplishment.' [RY]

- Accomplishment — dngos grub, Skt. siddhi, accomplishment is described as either supreme or common.

Supreme accomplishment is the attainment of buddhahood. Common accomplishments are the miraculous powers acquired in the course of spiritual training.

The attainment of these powers, which are similar in kind to those acquired by the practitioners of some non-Buddhist traditions, are not regarded as ends in themselves.

When they arise, however, they are taken as signs of progress on the path and are employed for the benefit of the teachings and disciples. [AJP] from The Great Image ISBN 1-59030-069-6

(1) dngos grub, Skt. siddhi. The fruit wished for and obtained through the practice of the instructions. Common accomplishments can be simply supernatural powers, but the term accomplishment can also refer to the supreme accomplishment, which is enlightenment.

(2) sgrub pa. In the context of the recitation of mantras. [MR]

It is important to know when you have let go of desire: when you no longer judge or try to get rid of it; when you recognise that it’s just the way it is.

When you are really calm and peaceful, then you will find that there is no attachment to anything. You are not caught up, trying to get something or trying to get rid of something. Well-being is just knowing things as they are without feeling the necessity to pass judgement upon them.

We say all the time, ‘This shouldn’t be like this!’, ‘I shouldn’t be this way!’ and, ‘You shouldn’t be like this and you shouldn’t do that!’ and so on. I’m sure I could tell you what you should be - and you could tell me what I should be.

We should be kind, loving, generous, good-hearted, hard-working, diligent, courageous, brave and compassionate.

I don’t have to know you at all to tell you that! But to really know you, I would have to open up to you rather than start from an ideal about what a woman or man should be, what a Buddhist should be . It’s not that we don’t know what we should be.

Our suffering comes from the attachment that we have to ideals, and the complexities we create about the way things are.

We are never what we should be according to our highest ideals. Life, others, the country we are in, the world we live in - things never seem to be what they should be. We become very critical of everything and of ourselves:

‘I know I should be more patient, but I just CAN’T be patient!’....

Listen to all the ‘shoulds’ and the ‘should nots’ and the desires: wanting the pleasant, wanting to become or wanting to get rid of the ugly and the painful. It’s like listening to somebody talking over the fence saying, ‘I want this and I don’t like that.

It should be this way and it shouldn’t be that way.’ Really take time to listen to the complaining mind; bring it into consciousness.

I used to do a lot of this when I felt discontented or critical. I would close my eyes and start thinking, ‘I don’t like this and I don’t want that’, ‘That person shouldn’t be like this’, and ‘The world shouldn’t be like that’.

I would keep listening to this kind of critical demon that would go on and on, criticising me, you and the world.

Then I would think, ‘I want happiness and comfort; I want to feel safe;

I want to be loved!’ I would deliberately think these things out and listen to them in order to know them simply as conditions that arise in the mind. So bring them up in your mind - arouse all the hopes, desires and criticisms.

Bring them into consciousness. Then you will know desire and be able to lay it aside.

The more we contemplate and investigate grasping, the more the insight arises: ‘Desire should be let go of.’

Then, through the actual practice and understanding of what letting go really is, we have the third insight into the Second Noble Truth, which is: ‘Desire has been let go of.’ We actually know letting go.

It is not a theoretical letting go, but a direct insight. You know letting go has been accomplished. This is what practice is all about.