Difference between revisions of "Through the Lens of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism"

m (Text replacement - "favorable " to "favorable ") |

|||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

For instance, the insatiability and addictive {{Wiki|tendencies}} of the [[hungry ghost]] are strategies for avoiding the [[rage]] and {{Wiki|depression}} of the [[hell realms]], where [[beings]] are depicted as [[suffering]] [[inconceivable]] torments—such as the repeated severing of limbs and gouging of eyeballs in settings of either extreme heat or cold, depending on the [[nature]] of the [[anger]] in whose [[grip]] one is held. This extreme [[aggression]] is, as {{Wiki|Freud}} (1917/1957) suggested of {{Wiki|depression}}, directed toward one’s [[own]] identifications of [[self]], and the [[pain]] of the [[hell realms]] thereby conveys the intensity of [[suffering]] that can arise when self-hatred and [[rage]] become extreme. | For instance, the insatiability and addictive {{Wiki|tendencies}} of the [[hungry ghost]] are strategies for avoiding the [[rage]] and {{Wiki|depression}} of the [[hell realms]], where [[beings]] are depicted as [[suffering]] [[inconceivable]] torments—such as the repeated severing of limbs and gouging of eyeballs in settings of either extreme heat or cold, depending on the [[nature]] of the [[anger]] in whose [[grip]] one is held. This extreme [[aggression]] is, as {{Wiki|Freud}} (1917/1957) suggested of {{Wiki|depression}}, directed toward one’s [[own]] identifications of [[self]], and the [[pain]] of the [[hell realms]] thereby conveys the intensity of [[suffering]] that can arise when self-hatred and [[rage]] become extreme. | ||

| − | The desperate [[grasping]] of the [[hungry ghost]] helps it avoid falling into the {{Wiki|terror}} of the [[hell realms]] and expresses its longing for the [[bliss]] of the [[god]] [[realm]], where [[beings]] are endowed with [[beauty]] and [[wealth]], and enjoy every conceivable [[pleasure]] ([[Trungpa]], 1973). In contemporary {{Wiki|Western culture}}, this [[desire]] to be a [[god]] is made [[visible]] in voyeuristic fascination with celebrities and their [[lives]]. However, we also exhibit the [[characteristics]] of the [[jealous]] gods—those who [[envy]] the [[gods]] and are paranoid about losing their [[own]] | + | The desperate [[grasping]] of the [[hungry ghost]] helps it avoid falling into the {{Wiki|terror}} of the [[hell realms]] and expresses its longing for the [[bliss]] of the [[god]] [[realm]], where [[beings]] are endowed with [[beauty]] and [[wealth]], and enjoy every conceivable [[pleasure]] ([[Trungpa]], 1973). In contemporary {{Wiki|Western culture}}, this [[desire]] to be a [[god]] is made [[visible]] in voyeuristic fascination with celebrities and their [[lives]]. However, we also exhibit the [[characteristics]] of the [[jealous]] gods—those who [[envy]] the [[gods]] and are paranoid about losing their [[own]] favorable position— whenever we wallow in a celebrity’s fall from grace. When we let go of such [[envy]] we can truly be [[human]], meaning that while we [[live]] in [[desire]], we are able to [[balance]] [[suffering]] with [[compassion]]. |

[[File:Maitreya sta.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Maitreya sta.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

When our [[suffering]] becomes too difficult to bear, however, we sink into the [[ignorance]] of the [[animal realm]], whereupon we may, for example, [[space]] out in front of our 46-inch flat screen TV. When that [[pleasure]] wears out, we are caught once again in the [[mindset]] of the [[hungry ghost]], desperately afraid of the [[hell realms]], and longing for the [[pleasures]] of the [[god]] [[realm]]. We return to the mall, opting for consumerism as our best chance at a {{Wiki|stable}} [[state of being]], albeit one that [[lives]] in [[fantasy]] and [[sacrifices]] [[compassion]]. {{Wiki|Neuroscientific}} {{Wiki|Materialism}} and the [[Hungry Ghost]] The underlying basis of the [[hungry ghost]], and of the MVO, can be found in the [[philosophical]] [[doctrine]] of [[dualism]], the position that [[mind]] and [[body]] are two completely different {{Wiki|substances}} (Karr, 2007). This [[view]] is ultimately untenable, leading to two predominant solutions: (1) reducing everything to material [[reality]], or {{Wiki|materialism}}, and (2) reducing everything to [[mind]], or {{Wiki|idealism}}. Contemporary [[traditional]] {{Wiki|neuroscience}} adopts the {{Wiki|materialist}} [[view]] in its assumption that [[mind]] is an emergent property of underlying {{Wiki|neurological}} {{Wiki|structure}} and [[function]]. Given that this approach frames most conversations about addiction, it is worth considering briefly what [[light]] it might shed on the [[hungry ghost]]. In this [[view]], the [[subjective]] [[mental]] [[experience]] of hunger arises from the complex interplay of numerous [[physical]] [[elements]], including a variety of {{Wiki|brain}} structures, {{Wiki|blood}} sugar levels, and {{Wiki|hormones}} (Le Magnen, 1985). | When our [[suffering]] becomes too difficult to bear, however, we sink into the [[ignorance]] of the [[animal realm]], whereupon we may, for example, [[space]] out in front of our 46-inch flat screen TV. When that [[pleasure]] wears out, we are caught once again in the [[mindset]] of the [[hungry ghost]], desperately afraid of the [[hell realms]], and longing for the [[pleasures]] of the [[god]] [[realm]]. We return to the mall, opting for consumerism as our best chance at a {{Wiki|stable}} [[state of being]], albeit one that [[lives]] in [[fantasy]] and [[sacrifices]] [[compassion]]. {{Wiki|Neuroscientific}} {{Wiki|Materialism}} and the [[Hungry Ghost]] The underlying basis of the [[hungry ghost]], and of the MVO, can be found in the [[philosophical]] [[doctrine]] of [[dualism]], the position that [[mind]] and [[body]] are two completely different {{Wiki|substances}} (Karr, 2007). This [[view]] is ultimately untenable, leading to two predominant solutions: (1) reducing everything to material [[reality]], or {{Wiki|materialism}}, and (2) reducing everything to [[mind]], or {{Wiki|idealism}}. Contemporary [[traditional]] {{Wiki|neuroscience}} adopts the {{Wiki|materialist}} [[view]] in its assumption that [[mind]] is an emergent property of underlying {{Wiki|neurological}} {{Wiki|structure}} and [[function]]. Given that this approach frames most conversations about addiction, it is worth considering briefly what [[light]] it might shed on the [[hungry ghost]]. In this [[view]], the [[subjective]] [[mental]] [[experience]] of hunger arises from the complex interplay of numerous [[physical]] [[elements]], including a variety of {{Wiki|brain}} structures, {{Wiki|blood}} sugar levels, and {{Wiki|hormones}} (Le Magnen, 1985). | ||

Latest revision as of 10:43, 29 January 2016

Modern Materialism International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 171

Modern Materialism

Through the Lens of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism

By Alan Pope

University of West Georgia

Carrollton, GA, USA

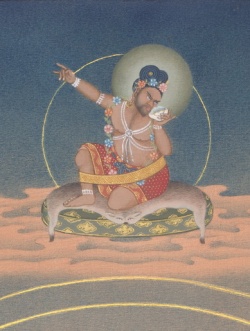

The suffering that gives rise to and is perpetuated by contemporary culture’s addiction to materialistic consumption is described surprisingly well by the ancient tradition of Indo- Tibetan Buddhism. From this perspective, modern human beings exemplify hungry ghosts trapped in a state of incessant greed and insatiability, which at its core reflects a desperate attempt to maintain a sense of self that is out of accord with basic reality. The rich Tibetan Buddhist understanding of the unfolding process by which the hungry ghost negotiates its project, including its attempts to avoid greater suffering and to seek bliss, serves to elucidate our contemporary psychological dynamic. This analysis points to what is needed in order to extract ourselves from a consumerist mentality and find genuine fulfillment. In Indo-Tibetan Buddhist iconography, the hungry ghost is a being whose massive, protruding belly is paired with a tiny pinhole mouth. Because it is able to consume but small bits of food at any one time, its huge stomach remains ever empty, and its limbs and torso scrawny. Although the Tibetan tradition speaks of hungry ghosts as denizens of a realm into which beings may incarnate, modern teachers emphasize that such realms are not places, but rather primordial states of mind familiar to us all (e.g., Trungpa, 1973, 1992).

As such, the hungry ghost symbolizes addictive greed and insatiability. In this paper, I use this image and the philosophy of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism to shed light on the state of mind made presently manifest through contemporary consumerist culture.1 In so doing, I look beyond materialism as simply a historical-cultural phenomenon, situating it as the outward expression of a mental state endemic to the human condition, one described with extraordinary detail by a spiritual tradition whose roots are more than 2500 years old. Modern Materialism The difficulties inherent in modern materialism have been well documented and empirically demonstrated (e.g., see Kasser, 2002; Kasser & Kanner, 2004).

Csikszentmihalyi (2004) defined materialism as “the tendency to allocate excessive attention to goals that involve material objects: wanting to own them, consume them, or flaunt possession of them” (p. 92). In this instance, excessive means exceeding survival and encroaching on other important areas of a person’s development and enjoyment. Kasser, Ryan, Couchman, and Sheldon (2004) described contemporary America’s culture of consumption as having a materialistic value orientation (MVO). Copious research suggests that an MVO develops both as compensation for an insecure self-image and through social exposure to materialistic models and values.

These studies also demonstrate that this approach leads to lower subjective well-being and diminished concern for the welfare of others and the environment. This latter aspect is not surprising given that overconsumption—through its exploitation of natural resources and polluting of the environment—is the driving force behind the accelerating ecological crisis (Starke & Mastny, 2010). The MVO operates under the premise that by consuming more and more goods, we can be happy (throughout this article, all uses of “we” and “our” refer to human beings in the collective sense, while acknowledging that the author writes from his own specific location in Western culture). But does this strategy work? When I buy that new 46-inch flat screen TV, I may enjoy it for some time, taking pride in my possession, displaying it for others to see. I enjoy the crisp, clean images of my favorite programs. I might International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 30(1-2), 2011, pp. 171-177 Keywords: hungry ghost, Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, materialistic value orientation, consumerism, neuromarketing, addiction, meditation 172 International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Pope spend countless hours watching it, freed momentarily from the other concerns and worries of my life.

However, there remains a deep longing that in fact the TV does not fulfill. The TV becomes another fixture to fade into the background of my life. My unfulfilled desire turns its attention to new objects that might satisfy it. I return to the shopping mall, looking for my next conquest, which I make, and then the cycle repeats. In Buddhist parlance, I am caught in the cycle of samsara, a compulsive repetition of suffering that thrives on my failure to recognize the source of my suffering and of my happiness (Ray, 2000). The Six Realms In Buddhist theory, samsara is depicted by six realms, known as that of the gods, jealous gods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts, and hell beings (see Patrul Rinpoche, 1994, for vivid descriptions). These realms represent different states of mind through which we cycle in the course of a human lifetime. They are interdependently connected, and so we cannot understand one without the other.

For instance, the insatiability and addictive tendencies of the hungry ghost are strategies for avoiding the rage and depression of the hell realms, where beings are depicted as suffering inconceivable torments—such as the repeated severing of limbs and gouging of eyeballs in settings of either extreme heat or cold, depending on the nature of the anger in whose grip one is held. This extreme aggression is, as Freud (1917/1957) suggested of depression, directed toward one’s own identifications of self, and the pain of the hell realms thereby conveys the intensity of suffering that can arise when self-hatred and rage become extreme.

The desperate grasping of the hungry ghost helps it avoid falling into the terror of the hell realms and expresses its longing for the bliss of the god realm, where beings are endowed with beauty and wealth, and enjoy every conceivable pleasure (Trungpa, 1973). In contemporary Western culture, this desire to be a god is made visible in voyeuristic fascination with celebrities and their lives. However, we also exhibit the characteristics of the jealous gods—those who envy the gods and are paranoid about losing their own favorable position— whenever we wallow in a celebrity’s fall from grace. When we let go of such envy we can truly be human, meaning that while we live in desire, we are able to balance suffering with compassion.

When our suffering becomes too difficult to bear, however, we sink into the ignorance of the animal realm, whereupon we may, for example, space out in front of our 46-inch flat screen TV. When that pleasure wears out, we are caught once again in the mindset of the hungry ghost, desperately afraid of the hell realms, and longing for the pleasures of the god realm. We return to the mall, opting for consumerism as our best chance at a stable state of being, albeit one that lives in fantasy and sacrifices compassion. Neuroscientific Materialism and the Hungry Ghost The underlying basis of the hungry ghost, and of the MVO, can be found in the philosophical doctrine of dualism, the position that mind and body are two completely different substances (Karr, 2007). This view is ultimately untenable, leading to two predominant solutions: (1) reducing everything to material reality, or materialism, and (2) reducing everything to mind, or idealism. Contemporary traditional neuroscience adopts the materialist view in its assumption that mind is an emergent property of underlying neurological structure and function. Given that this approach frames most conversations about addiction, it is worth considering briefly what light it might shed on the hungry ghost. In this view, the subjective mental experience of hunger arises from the complex interplay of numerous physical elements, including a variety of brain structures, blood sugar levels, and hormones (Le Magnen, 1985).

Normally, this system maintains homeostasis, alternating between experiences of hunger and, upon eating, satiety. However, what makes food potentially addictive is that eating also provides a jolt of dopamine, the same pleasureinducing neurotransmitter that is implicated in drugs of abuse (Avena, Rada, & Hoebel, 2008; Stoehr, 2006). If our baseline dopamine levels are depressed, we might consume food beyond the point of physical satiety, or take drugs purely to get high, both of which provide short-term relief with negative long-term consequences. Hence, even at the neurobiological level, the essential root cause of the hungry ghost’s insatiable hunger is likewise the basis for substance addiction more generally. However, this same physical root cause can lead to all manner of craving. For example, even the sight or smell of food in the absence of actual consumption induces the release of dopamine levels (Zurawicki, 2010).

Further, it has been shown that processing novel visual or cognitive information also elevates dopamine (in addition to activating opioid receptors in association areas of the cerebral cortex; Biederman & Vessel, 2006; Bromberg- Martin & Hikosaka, 2009). Thus, seeing food, smelling Modern Materialism International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 173 food, consuming drugs, viewing novel displays, thinking about interesting new things—all have the capacity to induce a chemical experience of pleasure and the craving that comes with it. A new discipline calling itself neuromarketing is exploiting these findings and applying them to the task of developing ways to maximize potential customers’ dopamine surges and other consumption-friendly biological processes (Zurawicki, 2010; Lindstrom, 2010). For example, if a product is displayed strategically, a dopamine rush will induce a purchase, even as the ensuing “crash” leaves us wondering what we were thinking (Lindstrom, 2010). Neurologically speaking, humans are wired for all manner of consumption, and advertisers—just as they have done in the past with behaviorism and psychoanalysis—are exploiting the latest trends in psychology in order to stimulate desire, increase profit, and populate the world with ever more hungry ghosts. Nevertheless, there is a growing body of evidence that this wiring can be changed. Neuroplasticity and Meditation Just as physics has advanced to the point that it has overthrown its earlier limiting assumptions, the work of Richard Davidson and other neuroscientists is challenging the presuppositions of traditional neuroscience.

In particular, they have demonstrated that the adult brain can change in response to experience, a phenomenon termed neuroplasticity (Lutz, Dunne, & Davidson, 2007). This view is largely based on studies with highly experienced meditators in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Using brain imaging equipment, Davidson and colleagues found that in meditation these individuals could easily slip into a pronounced pattern of asymmetrical firing in the prefrontal cortex (Begley, 2007). This pattern, in which the left cortex is extremely active relative to the right, signals the inner subjective experience of energized happiness, joy, and well-being. The extreme degree to which this pattern was demonstrated—far beyond what non-meditators exhibit—suggests the potential to rewire the brain through mental training. Whereas it used to be thought that the prefrontal cortex only pertains to the highest levels of abstract reasoning, and that the limbic system was the seat of emotions, it is now known that the prefrontal cortex is neurologically connected with and mediates the centers of emotional processing (Begley, 2007).

As such, cutting edge neuroscience is suggesting that mental training can change our relationship to our emotions, and that we can come to naturally have greater control over our urges and cravings. Actually, this is precisely what the Buddhist tradition teaches (Tsering, 2005). It stands to reason that studies of lower animals—generally the basis of addiction studies—will uncover the neurology of unmediated craving; however, investigations of highly conscious human beings show that neurological determinism is an inaccurate model. Human cognitive capacities can modulate emotional ones, and as such we need not be the puppet of advertisers and profiteers. The hungry ghost can be transformed. Beyond Materialism The studies by Davidson and his colleagues open onto even larger implications. They challenge the very assumptions of standard neurobiology—namely, that the mind is an emergent property of matter. If training the mind can affect neurology, then one must perhaps take seriously the suggestion made by the Dalai Lama (2005) that thoughts may give rise to chemical events. In that event, the brain should be viewed not as the origin of mind, but rather as mind’s executive officer.

The philosophical doctrine of materialism itself is thrown into question, and in turn it is necessary to question the cost of continuing to adopt it. In the words of Buddhist writer Andy Karr (2007), “these materialistic views can prevent us from understanding the causal relationships that are more important to us: the determinants of happiness and sorrow, bondage and liberation” (p. 79). In holding to a materialistic view, we look to the outer world for happiness, rather than looking within. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism regards idealism— besides materialism, the other proposed solution to the problem of dualism—as the superior position, recognizing that all experience is mental, meaning that it first registers in the mind (Karr, 2007). Although this view is developed in great detail in the Cittamatra, or Mind Only School of Mahayana Buddhism, it is ultimately recognized as only partially correct, for the One Mind is itself a concept that is superimposed on reality (Gyamtso, 1994). The Madhyamaka, or Middle- Way, teachings of Mahayana Buddhism assert that everything is ultimately neither mind nor matter, because neither ultimately exists.

Rather, they both arise together, interdependently. It is only when we appeal to concepts that we see either mind or matter as prior. When we realize the middle way position, placing primacy on neither the mind nor material 174 International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Pope reality, we see vividly that the ego, or sense of “I,” is an illusion. It neither exists in a solid way (the doctrine of eternalism), nor does it not exist altogether (the doctrine of nihilism). In order to escape the endless cycling through the six realms, we must see through our habituated patterns and realize the true nature of the self. When we closely examine the body, we see that it is composed of a collection of parts, such as blood, skin, sensory organs, internal organs, nerves, and so forth. These parts are composed of ever-smaller particles, none of which has an intrinsic, separate existence. If we examine the mind, we find an overlapping stream of thoughts, feelings, impressions, and sensations, none of which exists independently. What we call a self is really a succession of experiences onto which we have imputed various concepts, the most central one being “I.” That is, our sense of self is a fiction, a story we tell ourselves to give coherency to our experience. It exists not as a solid entity, but rather as a character in a social fabric of conceptual understanding and storytelling. Interdependent Existence The MVO is an integral part of the contemporary social fabric that gives definition and shape to our sense of self. In its part, the ego is not interested in consuming materials goods in an authentic sense; rather, what the ego consumes is symbols.

It is what things represent, what they tell about us—whether we are successful, affluent, desirable, or superior—that establishes their worth. In the meantime, we are actually covering over a tremendous sense of lack, hiding from the fact that we do not exist in the ways we conventionally think that we do. As David Loy (1996) has suggested, this lack is the deepest source of our anxiety, more fundamental even than the fear of death. In order to comfort ourselves in the face of this lack, we bow to what Chögyam Trungpa (1973) characterized as The Three Lords of Materialism: those of Form, Speech, and Mind. Of the first one, he explained: The Lord of Form refers to the neurotic pursuit of physical comfort, security, and pleasure. Our highly organized and technological society reflects our preoccupation with manipulating physical surroundings so as to shield ourselves from the irritations of the raw, rugged, unpredictable aspects of life…The Lord of Form does not signify the physically rich and secure life-situations we create per se. Rather it refers to the neurotic preoccupation that drives us to create them, to try to control nature. (pp. 5-6) The deep source of our consumerist mentality can be seen in this neurotic pursuit of comfort, security and pleasure, the compulsion to control the seeming chaos of life. This approach to life reflects a basic confusion about ourselves and our actions. When we recognize that mind and matter arise together, and that we do not exist in an intrinsic and separate way, we realize that no one phenomenon can appear except in interdependent relationship with all other phenomena.

This realization invites a deeper understanding of the consequences of our consumerist actions. We recognize not only that habitual consumption is not in the service of our own happiness—it is as well deeply unethical, for its far-ranging impact places our collective survival in jeopardy. Genuine Happiness In the most basic sense, the MVO cannot promote true happiness because it is based on a principle of satisfaction rather than fulfillment. When we seek satisfaction, we seek the external conditions whereby we can feel temporarily sated. Inevitably, however, as conditions change, these states of satiation fade and new hunger arises. Even so, the ancient philosophical doctrine of hedonism regarded the pursuit of pleasure as the highest good (Kashdan, Biswas-Diener, & King, 2008). In its subtler versions, such as that expressed by Epicurus, a greater happiness necessitates that we use moderation in order that excessive indulgence not lead to excessive pain (De Lacy, 1967). Nevertheless, in this view happiness depends on the manipulation of external circumstances in the pursuit of more rather than less (pleasure).

Given that pleasure can only be defined in contrast to pain, happiness is necessarily relative and fleeting. Insofar as Freud’s economic model considered the pursuit of pleasure to be the ultimate motivating force of psyche, we can understand how it is that a successful psychoanalytic treatment aims merely to bring ordinary unhappiness to its patients (Freud, 1895/1955). It is laudable that the hedonistic view values immediate experience, for otherwise we would live in our thoughts about the past or the future, separated from reality as it is. However, that which is revealed in our immediate experience varies depending on the state of our mind. For example, we can be immediately present Modern Materialism International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 175 to feelings of greed or hatred without recognizing that such feelings are transitory and ultimately empty of any substantial reality. Immediacy without genuine presence leaves us vulnerable to surfing a series of ever-pressing desires and aversions. Instead, we must train our minds to rest in a panoramic awareness that sees mental states such as greed and hatred as adventitious phenomena that cannot touch the deep sense of our true nature. From this perspective, genuine fulfillment or happiness, rather than being the accumulation of pleasures, is “a deep sense of flourishing that arises from an exceptionally healthy mind” (Ricard, 2003, p. 19). From a Buddhist perspective, such mental health is gained through disciplined mental training of no less effort than that used to maintain our physical bodies in peak condition.

Through the practices of contemplation and meditation we can face our fears and discomforts in a disciplined way. When we confront them directly, their force is diminished, for it is what we do not see that unnerves us. A mind that is consequently calm and balanced can withstand any external circumstance. While such happiness can be regarded as an objective state relating to the condition of one’s awareness, it has subjective correlates. When times are prosperous, the fulfilled mind experiences joy; when times are difficult, it responds with courage (DeWit, 2001, March). Rather than being passive to events in the world, we choose the ways we interpret and respond to them. Rather than being a temporary experience, genuine happiness is an optimal state of being (Ricard, 2003). This form of happiness resembles the Hellenic concept of eudaimonia, which for Aristotle was an objective condition associated with living a life of contemplation and virtue (Waterman, 2008). Drawing upon the work of contemporary philosopher David Norton, Waterman (2008) explained: “Eudaimonia was seen as a consequence of ‘living in truth to one’s daimon’ or ‘true self,’ when an individual strives toward excellence in fulfilling his or her personal potentials” (pp. 235-236). At this level, we can see Buddhist happiness as a strong form of eudaimonia in which the true self to be realized is the no-self, the self that exists beyond all concepts. However, the Greek conception of eudaimonia, particularly in its contemporary interpretation, preserves the sense of the self as intrinsic and separate. Waterman goes on to observe that whereas daimon originally meant guiding spirit, contemporary theorists regard it as a constellation of interrelated psychological processes.

Although this description resonates with the Buddhist notion of the ego as a continuum of {{Wiki|psychophysical]] events, it does not accord with Buddhism’s understanding of our deepest nature. That is, it does not explicitly account for realizing our transpersonal potentials, those that enable us to let go of even the subtlest traces of greed and protective selfcherishing. Regaining the Natural State According to the Madhyamaka Shentong teachings of Tibetan Buddhism, all humans have the same basic nature at the core of their Being (Maitraya, 2000). This so-called buddha-nature is naturally and spontaneously wise, loving, and compassionate. However, it is obscured to the extent that we cling to ego identifications that keep the natural qualities of ourselves and our experience cloaked by layers of conceptual artifice. When that conceptual artifice, erected and maintained with the support of consumerist culture, tells us to seek pleasure and avoid pain—and not only sanctions shopping, but regards it as a nationalistic duty—then we are kept in a state of alienation from ourselves and from one another. We live as hungry ghosts, unable to really touch the material world, unable to touch each other, and unable to be sated in any meaningful way. We are removed from the possibility of genuine fulfillment. Genuine fulfillment arises to the extent that we can put the needs of others before our own. Such altruism is not simply a “random act of kindness”; rather, in Tibetan Buddhist thought it is a pervasive modality of being that we must cultivate in order to recover our true nature. Given that we are interdependent rather than independent beings, to think only of ourselves is to live out of accord with reality and to create the conditions for suffering. The material sensibilities of the modern age inculcate this deluded perception in us, imprisoning us in a vicious circle of heightened pleasure and subsequent pain. The way to overcome this state of affairs is to confront the fear and grief from which we are hiding, whereupon shopping will lose its appeal in favor of human connection and caring. References Avena, N. M., Rada, P., & Hoebel, B. G. (2008). Evidence for sugar addiction: Behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake.

Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32, 20-39. 176 International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Pope Begley, S. (2007). Train your mind, change your brain: How a new science reveals our extraordinary potential to transform ourselves. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. Biederman, I., & Vessel, E. A. (2006, June). Perceptual pleasure and the brain. American Scientist, 93, 249-255. Bromberg-Martin, E., & Hikosaka, O. (2009). Midbrain dopamine neurons signal preference for advance information about upcoming rewards. Neuron, 63, 119-126. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004). Materialism and the evolution of consciousness. In T. Kasser & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Psychology and consumer culture. Washington, DC: Amerian Psychological Association. Dalai Lama. H. (2005). The universe in a single atom: The convergence of science and spirituality. New York, NY: Morgan Road Books. De Lacy, P. H. (1967). Epicurus. In P. Edwards (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Vol. 3, pp. 3-5). New York, NY: Macmillan & Free Press. De Wit, H. F. (2001, March). The case for contemplative psychology. Shambhala Sun, 34-37. Freud, S. (1895/1955). Studies of hysteria (Vol. 2). London, UK: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psychoanalysis. Freud, S. (1917/1957). Mourning and melancholia (J. Strachey, Trans.). In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 237-260). London, UK: Hogarth Press. Gyamtso, K. T. (1994). Progressive stages of meditation on emptiness. Auckland, New Zealand: Zhyisil Chokyi Ghatsal. Karr, A. (2007). Contemplating reality: A practitioner’s guide to the view in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Boston, MA: Shambhala. Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4), 219. Kasser, T. (2002). The high price of materialism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Kasser, T., & Kanner, A. D. (Eds.). (2004). Psychology and consumer culture. Washington, DC: American Psychological Asscociation. Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences. In T. Kasser & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Psychology and consumer culture. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. Le Magnen, J. (1985). Hunger. London, UK: Cambridge University Press. Lindstrom, M. (2010). Buy-ology: The new science of why we buy. New York, NY: Broadway Books. Loy, D. (1996). Lack and transcendence: The problem of death and life in psychotherapy, existentialism, and Buddhism. Amherst, NY: Humanity Books. Lutz, A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2007). Meditation and the neuroscience of consciousness: An introduction. In P. D. Zelazo, M. Moscovitch, & E. Thompson (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of consciousness (pp. 499-551). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Maitraya, A. (2000). Buddha nature: The Mahayana Uttaratantra Shastra with commentary (R. Fuchs, Trans.). Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion. Patrul Rinpoche. (1994). The words of my perfect teacher. The sacred literature series. New York, NY: HarperCollins. Ray, R. A. (2000). Indestructible truth: The living spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism. Boston, MA: Shambhala. Ricard, M. (2003). Happiness: A guide to developing life’s most important skill. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company. Starke, L., & Mastny, L. (Eds.). (2010). State of the world 2010: Transforming cultures: From consumerism to sustainability. New York, NY: W. W. Norton. Stoehr, J. (2006). The neurobiology of addiction. Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House. Tsering, T. (2005). The four noble truths. Boston, MA: Wisdom. Trungpa, C. (1973). Cutting through spiritual materialism. Boston, MA: Shambhala. Trungpa, C. (1992). Transcending madness: The experience of the six bardos. Boston, MA: Shambhala. Waterman, A. S. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: A eudaimonist’s perspective. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4), 234. Zurawicki, L. (2010). Neuromarketing: Exploring the brain of the consumer. London, UK: Springer. Notes 1. The term Indo-Tibetan Buddhism acknowledges that the rich philosophical tradition of Tibetan Buddhism has deep roots in Indian culture, from whence Buddhism migrated to Tibet. Modern Materialism International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 177 About the Author Alan Pope, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of West Georgia. Following advanced graduate studies in computer science and artificial intelligence (Ph.D./ABD), he received his doctorate in clinical existential-phenomenological psychology at Duquesne University (2000). In addition, for the past 20 years he has studied and practiced within the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition. His research generally seeks to elucidate the processes of psycho-spiritual transformation resulting from involuntary suffering and through disciplined spiritual and creative practice. His recent work examines various aspects of Western psychology and culture through the lens of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. He is the author of From Child to Elder: Personal Transformation in Becoming an Orphan at Midlife (2006, Peter Lang). He was the 2009 recipient of Division 32 (APA)’s Carmi Harari Early/Mid Career Award for Outstanding Contribution to Inquiry in Humanistic and Transpersonal Psychology. About the Journal The International Journal of Transpersonal Studies is a peer-reviewed academic journal in print since 1981. It is published by Floraglades Foundation, and serves as the official publication of the International Transpersonal Association. The journal is available online at www. transpersonalstudies.org, and in print through www. lulu.com (search for IJTS).