Difference between revisions of "What does ‘Vibhajjavāda’ mean?"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | <nomobile>{{DisplayImages|2583|2843|2280|2551|3880|2194|4144|2474|1246|4557}}</nomobile> | |

Revision as of 15:45, 3 March 2016

What does ‘Vibhajjavāda’ mean?

So we are left with the problem: what did vibhajjavāda mean, and why was it relevant in the context of the Third Council?

Let us recall the flow of the text.

The non-Buddhist heretics assert various doctrines of the ‘self’; Moggaliputtatissa opposes them with the Buddha’s doctrine of vibhajjavāda; then the Mahāvihāra sources depict him as going on to teach the Kathāvatthu.

Even if the Kathāvatthu was a later addition, the Mahāvihāra must have added it for some reason.

The Kathāvatthu commentary, as we have seen, specifically says that the Kathāvatthu ‘distinguishes’ (vibhajanto) the heterodox and orthodox views, so perhaps it means to make some explicit connection between the Kathāvatthu and the vibhajjavāda.

Now, the Kathāvatthu discusses very many topics, many of which are trivial and are given little space, and far outweighing all other topics in the book is the first section, the discussion of the ‘person’.

This is, as we have seen, the only main topic common to the Kathāvatthu and the Vijñānakāya, apart from the opposing positions on the ‘all exists’ thesis.

It was clearly a difficult controversy, and despite the cool Abhidhamma dialectic, an emotional one.

In our present context, surely the emerging theme is this self/not-self debate. I would like to suggest that the term vibhajjavāda is used here to imply a critique of the non-Buddhist theory of Self.

This would certainly fulfil the criteria we asked for earlier, that the term must evoke a pithy, essential aspect of the Buddha’s teaching in a way that would answer the challenge of the heretics.

The teaching of not-self has always been regarded as a central doctrine of the Buddha.

A characteristic method used by the Buddhists to break down the false idea of self was to use analysis.

In early Buddhism, the main method was to systematically determine those things which are taken to be the self, hold them up for investigation, and find on scrutiny that they do not possess those features which we ascribe to a self.

Thus the five aggregates are described as forming the basis for self theories.

But on reflection, they are seen to lead to affliction, which is not how a self is conceived, so they fail to fulfil the criteria of a self.

In the Suttas, this method was exemplified by the disciple Kaccāyana, who was known as the foremost of those able to analyse (vibhajjati) in detail what the Buddha taught in brief; the Dīpavaṁsa says that he filled that role in the First Council.196

This analysis, or vibhaṅga, gathered momentum during the period of the Third Council.

Indeed, the basic text is called, in the Mahāvihāravāsin version, the Vibhaṅga;

the Sarvāstivāda version is the Dharmaskandha, and the Dharmaguptaka version is the Śāripūtrābhidharmaśāstra.

These all stem from an ancient phase of Abhidhamma development, collecting the ‘analytical’ Suttas, primarily arranged according to the topics of the Saṁyutta Nikāya/Āgama, and elaborating them with varying degrees of Abhidhammic exegesis.

So it would make perfect sense in our narrative for vibhajjavāda to represent the Abhidhamma movement as an analytic approach to Dhamma in general, and as a critique of the ‘self’ in particular.

It would also seem appropriate to describe the Buddha as a vibhajjavādin, equivalent to saying he was an anattavādin.

This interpretation must remain tentative, since it cannot be backed up with a clear statement from the texts. Yet, as we have seen, the definitions of vibhajjavāda that we are offered by the texts are inadequate to explain the usage by the Mahāvihāravāsins in their own texts:

they are late, or irrelevant, or derived from a different school.

If our speculations have any value, it would seem that the prime target of the polemics in this passage are not the Sarvāstivādins, but the non-Buddhist Self theorists, and perhaps by implication the Puggalavādins.

But there is another, quite different, aspect of the term vibhajjavāda that is suggested by our sources.

When the troubles in the Sangha proved intractable, king Aśoka asks his ministers who can resolve the problems.

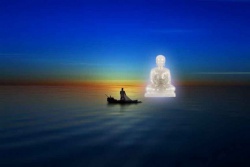

They suggest Moggaliputtatissa, and so the king orders that he be fetched on a boat.

Aśoka dreams that a white elephant will arrive and take him by the hand; accordingly, the next morning Moggaliputtatissa arrives, and, wading in the water to help him, the king and the Elder clasp each others’ hand.

This is a serious breach of royal taboos, and the guards draw their swords threateningly before being restrained by the king.

All this acts as a significant mythic precursor to the Third Council.

With the exception of the king’s dream, these events closely mirror events surrounding Upagupta; Moggaliputtatissa and Upagupta share such a close mythos that several scholars have seriously argued that they are the same monk.

The only significant difference between the two in this instance is the dream sequence, which echoes the dream of the Buddha’s mother before she was born, suggesting that Moggaliputtatissa, like Upagupta, is a ‘second Buddha’.197

The white elephant is also one of the seven ‘treasures’ of a Wheel-turning Monarch.

But next is another episode, which as far as I can see has no parallel with Upagupta.

The king asks to see a miracle of psychic power: he wants Moggaliputtatissa to make the earth quake.

The Elder asks whether he wants to see the whole earth shake, or only a part of it, saying it is more difficult to make only part shake, just as it is more difficult to make only half a bowl of water tremble.

Accordingly, the king asks to see a partial earthquake, and on the Elder’s suggestion, he places at a league’s distance in the four directions a chariot, a horse, a man, and a bowl of water respectively, each half in and half outside the boundary.

The Elder, using fourth jhana as a basis, determines that all the earth within a league should tremble: accordingly it does so, with such precision that the inside wheel of the chariot trembles,

but not that outside the boundary, and the same for the horse, the man, and even the bowl of water.

It was this miracle that convinced Aśoka that Moggaliputtatissa was the right man to stabilize the sāsana.198

The crucial value here is the precision with which the Elder can resolve his psychic abilities, dividing the earth as if with a razor.

This concern for precision, orderliness, and clean boundaries is characteristic of the Mahāvihāravāsin school, which evinces a philosophical revulsion for grey areas, graduations, and ambiguities.

For example, while other schools asserted that rebirth took place through a gradual transitional phase called the ‘in-between existence’, the Mahāvihāravāsins would have none of that, declaring that one life ends and the next begins in the following moment.

Or while many schools spoke of a gradual penetration to the Dhamma (anupubbābhisamaya), the Mahāvihāravāsins developed the idea that penetration happens all-at-once (ekābhisamaya).

Similarly, when explaining the ‘Twin Miracle’ where the Buddha was supposed to simultaneously emit both water and fire:

the point of the miracle would seem to be the fusion of opposites, but for the Mahāvihāravāsins there is no fusion, the miracle is an example of how fast the Buddha could advert between a water-kasiṇa and fire-kasiṇa, flashing back and forth to create the illusion of simultaneity.

This notion of a momentary flickering back and forth to explain what the text would appear to present as synthesis is found elsewhere, too.

In satipatthana the meditator first contemplates ‘internally’ then ‘externally’, then ‘internally/externally’.

While the Suttas regard this ‘internal/external’ contemplation as the comprehension that there is no fundamental difference between the two, the Mahāvihāravāsins explained it as a rapid flicking back and forth.

Similarly, the Suttas speak of ‘samatha and vipassana yoked together’, evidently imagining a concurrent balance of these qualities in a meditator’s consciousness.

While the Mahāyāna sources seem to retain this understanding, the Mahāvihāravāsins again speak of a rapid alteration between the two.

This admittedly ill defined sense of ‘clear-cut-ness’ that we see in the Mahāvihāravāsins may also be implied in the usage of vibhajjavādin.

There is one final implication in the word vibhajjavādin in this account.

One of the most dramatic episodes concerns Aśoka’s initial attempt to heal the problems in the Sangha.

He instructs a minister to go and order the monks to do uposatha.

The minister is told by the good monks that they refuse to do uposatha with the heretics.

The minister, misunderstanding Aśoka’s intention, starts beheading the obstinate monks.

He only stops when it he realizes that the next monk in line to have his head chopped off is none other that Tissa, the king’s brother.

He returns to inform Aśoka, who is understandably seized by remorse, rushes to apologize to the monks, and asks whether he is to be held karmically responsible.

The monks tell him different stories: some say he is to blame, some say he and the minister share the blame, while some say that only acts done intentionally reap a karmic result—as he had no intention there is no blame.

But none of them can assuage his doubt.

Only Moggaliputtatissa can do this.

The Elder is then sent for, and after his arrival in the boat and subsequent demonstration of his psychic powers, the king is able to accept his explanation: there is no intention, therefore there is no guilt.

This episode reminds us of the spectacular State visit by Ajātasattu to the Buddha, where he similarly confessed to a great crime and was comforted by the Buddha.

In both cases the king was unable to find peace of mind until hearing the Dhamma from the right person.

In this careful analysis of the distinction between physical and mental acts we see another possible meaning of vibhajjavādin.

This was a crucial doctrine that marked off the Buddhists from otherwise similar groups such as the Jains.

We have seen that Mahādeva similarly invokes such a distinction to justify his acts.

Thus vibhajjavāda might have a variety of meanings in this context.

Perhaps we should not seek for a definitive answer. As a mythic text, the passage is evoking a style, an atmosphere for the school, not laying down definitions.

It may be that we can go no further than to explore various possibilities.

After all, the school itself did not try to close off the specific denotation of the word.

But the important conclusion of this discussion is that we can find plenty of implications in the term vibhajjavāda, whether those explicitly offered by the tradition, or those speculatively inferred from context, that do not involve sectarian differences.

This stands in marked contrast to the often assumed conception of vibhajjavāda as the opposite of sarvāstivāda, which we examine next.

Source

http://santifm.org/santipada/2010/more-on-the-vibhajjavadins/ [[Category:]]