Difference between revisions of "Resolving the mind"

m (Text replacement - "]]]" to "]])") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DisplayImages|1951|2553|2186|3054|2354|33|3491}} | {{DisplayImages|1951|2553|2186|3054|2354|33|3491}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

[[Buddha's]] [[Enlightenment]] | [[Buddha's]] [[Enlightenment]] | ||

| Line 11: | Line 19: | ||

| − | On top of [[Vulture Peak]] [[Shakyamuni]] was expounding the [[Dharma]]. Undoubtedly it was a place of great scenic [[beauty]] and sanctity. As usual, [[Shakyamuni's]] [[Ten Great Disciples]] along with {{Wiki|innumerable}} followers [[gathered]] like clouds. On that day [[Shakyamuni]] wanted to clarify the {{Wiki|matter}} of a [[Dharma heir]] and at the same [[time]] express his [[feelings]] about the [[Dharma]]. Unlike any occasion previously, he began his {{Wiki|sermon}} for the sake of finding an heir. He gently held up a [[lotus flower]] in his hand. Describing the figure in words, that is what appeared optically. But for the imperceivable [[mind]] which {{Wiki|transcends}} [[phenomenon]], [[Shakyamuni's]] entire [[body]] became the [[lotus flower]]. When the [[self]] disappears, when the gap, or {{Wiki|interval}} is removed, things are just themselves, as they are. There is nothing other than the thing itself. So there was no [[Shakyamuni]]. When this fact is clearly comprehended, it stands to [[reason]] that one must consent to "the thing is simply the thing itself." It seemed no one there on [[Vulture Peak]] could [[grasp]] at all this fact. They all only wondered, What's this all about? | + | On top of [[Vulture Peak]] [[Shakyamuni]] was expounding the [[Dharma]]. Undoubtedly it was a place of great scenic [[beauty]] and sanctity. As usual, [[Shakyamuni's]] [[Ten Great Disciples]] along with {{Wiki|innumerable}} followers [[gathered]] like clouds. On that day [[Shakyamuni]] wanted to clarify the {{Wiki|matter}} of a [[Dharma heir]] and at the same [[time]] express his [[feelings]] about the [[Dharma]]. Unlike any occasion previously, he began his {{Wiki|sermon}} for the [[sake]] of finding an heir. He gently held up a [[lotus flower]] in his hand. Describing the figure in words, that is what appeared optically. But for the imperceivable [[mind]] which {{Wiki|transcends}} [[phenomenon]], [[Shakyamuni's]] entire [[body]] became the [[lotus flower]]. When the [[self]] disappears, when the gap, or {{Wiki|interval}} is removed, things are just themselves, as they are. There is nothing other than the thing itself. So there was no [[Shakyamuni]]. When this fact is clearly comprehended, it stands to [[reason]] that one must consent to "the thing is simply the thing itself." It seemed no one there on [[Vulture Peak]] could [[grasp]] at all this fact. They all only wondered, What's this all about? |

| Line 55: | Line 63: | ||

[[Shakyamuni]] was the son of the {{Wiki|prince}} of [[Magadha]], a large country located in what is now [[India]]. He enjoyed many [[pleasures]]. But his [[intellectual]] growth and expansion fueled his [[doubts]] and [[suffering]] day by day. The [[living Buddha]] had already matured enough that his [[thoughts]] were turning inward. Usually one's interests turn outward to externals for [[pleasure]] and [[enjoyment]]. The response to external {{Wiki|stimulation}} through the doors of [[perception]] and the [[senses]] is immediate. But from [[birth]] [[Shakyamuni]] had gone {{Wiki|past}} the stage of external {{Wiki|stimulation}}. In other words, his {{Wiki|conception}} of external {{Wiki|stimuli}} was not founded in personal interests. His [[fate]] or [[reason]] for living was that each event that took place in his [[life]] [[manifested]] as a problem. They were the problems of [[birth]], [[old age]], [[sickness]], and [[death]]. His [[view]] of a festive scene full of beautiful dancers and smiling faces was, "What's the [[sense]] of all this? Another day is quickly passing. I'm not amused by it all. Wasting my [[time]] at this only piles a [[sense]] of futility on top of my [[suffering]]." And when the young [[Shakyamuni]] looked at [[flowers]] blooming in spring, he [[thought]], "Yes, they are beautiful now, but soon they will rot away and look detestable...........people get carried away by [[seeing]] a beautiful [[flower]], and deceive themselves all the more by putting on a showy banquet." | [[Shakyamuni]] was the son of the {{Wiki|prince}} of [[Magadha]], a large country located in what is now [[India]]. He enjoyed many [[pleasures]]. But his [[intellectual]] growth and expansion fueled his [[doubts]] and [[suffering]] day by day. The [[living Buddha]] had already matured enough that his [[thoughts]] were turning inward. Usually one's interests turn outward to externals for [[pleasure]] and [[enjoyment]]. The response to external {{Wiki|stimulation}} through the doors of [[perception]] and the [[senses]] is immediate. But from [[birth]] [[Shakyamuni]] had gone {{Wiki|past}} the stage of external {{Wiki|stimulation}}. In other words, his {{Wiki|conception}} of external {{Wiki|stimuli}} was not founded in personal interests. His [[fate]] or [[reason]] for living was that each event that took place in his [[life]] [[manifested]] as a problem. They were the problems of [[birth]], [[old age]], [[sickness]], and [[death]]. His [[view]] of a festive scene full of beautiful dancers and smiling faces was, "What's the [[sense]] of all this? Another day is quickly passing. I'm not amused by it all. Wasting my [[time]] at this only piles a [[sense]] of futility on top of my [[suffering]]." And when the young [[Shakyamuni]] looked at [[flowers]] blooming in spring, he [[thought]], "Yes, they are beautiful now, but soon they will rot away and look detestable...........people get carried away by [[seeing]] a beautiful [[flower]], and deceive themselves all the more by putting on a showy banquet." | ||

| − | [[Shakyamuni]] had a beautiful wife of a [[noble]] family and one son [[Ragora]]. But still he would muse, "Man's [[life]] is governed by [[fate]] and [[evolution]]. In youth we are beautiful and lively. Why does man fall into [[sickness]], become old, and finally [[die]]? Neither my [[parents]], wife, child, nor myself can avoid this. How did this severe law of [[reality]] come about?" The more he investigated his [[misery]] through study and [[philosophy]] the more he [[suffered]]. | + | [[Shakyamuni]] had a beautiful wife of a [[noble]] [[family]] and one son [[Ragora]]. But still he would muse, "Man's [[life]] is governed by [[fate]] and [[evolution]]. In youth we are beautiful and lively. Why does man fall into [[sickness]], become old, and finally [[die]]? Neither my [[parents]], wife, child, nor myself can avoid this. How did this severe law of [[reality]] come about?" The more he investigated his [[misery]] through study and [[philosophy]] the more he [[suffered]]. |

| − | What happened was that his [[world]] of [[pleasure]] [[arising]] from [[influences]] on the coarse or lower [[human]] response functions was at an end. It is said that [[Shakyamuni]] made 8000 journeys to the ordinary [[world]] of man. Making this many trips to the regular [[world]] he came to the conclusion that no {{Wiki|matter}} how much one indulges in [[pleasure]], the result is [[sorrow]] and [[grief]] and the [[realization]] of the futility of it all. All things and affairs of the [[phenomenal world]] eventually [[decay]] and uselessly [[die]]. Through personal [[experience]] Skakyamuni firmly grasped this [[reality]], both conceptually and [[philosophically]]. If one's sentiment is moved by deep [[intellectual]] [[understanding]] and [[metaphysics]] and a [[feeling]] for transiency, pathos, and nihility, then one's decision-making {{Wiki|processes}} are going to lead in a certain [[direction]]. All of his [[human]] qualities, including {{Wiki|empathy}}, {{Wiki|responsibility}}, and [[wisdom]] had been refined and polished through his 8000 crossings into the [[world]] of man. He certainly understood his family's tugs and pleas for more [[love]] and [[attention]], but there was something else that had unyieldingly seized him. He had already transcended the [[self-centered]] [[world]] and reached the [[absolute]], which was his [[universal]] Great [[Doubt]]. This Great [[Doubt]] is what made the man [[Shakyamuni]] a [[Buddha]]. | + | What happened was that his [[world]] of [[pleasure]] [[arising]] from [[influences]] on the coarse or lower [[human]] response functions was at an end. It is said that [[Shakyamuni]] made 8000 journeys to the ordinary [[world]] of man. Making this many trips to the regular [[world]] he came to the conclusion that no {{Wiki|matter}} how much one indulges in [[pleasure]], the result is [[sorrow]] and [[grief]] and the [[realization]] of the futility of it all. All things and affairs of the [[phenomenal world]] eventually [[decay]] and uselessly [[die]]. Through personal [[experience]] Skakyamuni firmly grasped this [[reality]], both conceptually and [[philosophically]]. If one's sentiment is moved by deep [[intellectual]] [[understanding]] and [[metaphysics]] and a [[feeling]] for transiency, [[pathos]], and nihility, then one's decision-making {{Wiki|processes}} are going to lead in a certain [[direction]]. All of his [[human]] qualities, [[including]] {{Wiki|empathy}}, {{Wiki|responsibility}}, and [[wisdom]] had been refined and polished through his 8000 crossings into the [[world]] of man. He certainly understood his family's tugs and pleas for more [[love]] and [[attention]], but there was something else that had unyieldingly seized him. He had already transcended the [[self-centered]] [[world]] and reached the [[absolute]], which was his [[universal]] Great [[Doubt]]. This Great [[Doubt]] is what made the man [[Shakyamuni]] a [[Buddha]]. |

| − | This Great [[Doubt]] was rooted in the utter futility of all relationships with the common [[world]] of [[humanity]]. This included his [[worldly]] position as [[king]], his castle and possessions, and his home and family. Here his [[suffering]] reached its [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] limit. Finally, greeting his [[fate]], he cut off all [[worldly]] relations and threw away his castle. He was nineteen. [Other sources [[state]] his age at 29. But this is [[doubtful]] because he would have been middle-aged in those days.] | + | This Great [[Doubt]] was rooted in the utter futility of all relationships with the common [[world]] of [[humanity]]. This included his [[worldly]] position as [[king]], his castle and possessions, and his home and [[family]]. Here his [[suffering]] reached its [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] limit. Finally, greeting his [[fate]], he cut off all [[worldly]] relations and threw away his castle. He was nineteen. [Other sources [[state]] his age at 29. But this is [[doubtful]] because he would have been middle-aged in those days.] |

Prepared even to [[die]], he left his castle with six companions in order to resolve the Great Matter. His sights were on the other shore. This was truly an example of [[Bodaishin]], the [[Mind]] that seeks the Way. What could stand in his [[path]]! Know that [[Bodaishin]] itself is the [[life]] of the [[buddhas]] and [[patriarchs]]. | Prepared even to [[die]], he left his castle with six companions in order to resolve the Great Matter. His sights were on the other shore. This was truly an example of [[Bodaishin]], the [[Mind]] that seeks the Way. What could stand in his [[path]]! Know that [[Bodaishin]] itself is the [[life]] of the [[buddhas]] and [[patriarchs]]. | ||

Latest revision as of 07:55, 16 February 2024

Buddha's Enlightenment

From a paper by:

Kido Inoue

SHORINKUTSU-DOJO

PRESENTED BY:

the Wanderling

On top of Vulture Peak Shakyamuni was expounding the Dharma. Undoubtedly it was a place of great scenic beauty and sanctity. As usual, Shakyamuni's Ten Great Disciples along with innumerable followers gathered like clouds. On that day Shakyamuni wanted to clarify the matter of a Dharma heir and at the same time express his feelings about the Dharma. Unlike any occasion previously, he began his sermon for the sake of finding an heir. He gently held up a lotus flower in his hand. Describing the figure in words, that is what appeared optically. But for the imperceivable mind which transcends phenomenon, Shakyamuni's entire body became the lotus flower. When the self disappears, when the gap, or interval is removed, things are just themselves, as they are. There is nothing other than the thing itself. So there was no Shakyamuni. When this fact is clearly comprehended, it stands to reason that one must consent to "the thing is simply the thing itself." It seemed no one there on Vulture Peak could grasp at all this fact. They all only wondered, What's this all about?

And it seems that the present situation here is no different from that time long ago.

However, there was a celebrated follower of Shakyamuni who saw through the mind/heart of his teacher and master. One person there, Mahakasyapa, grasping it all broke into a smile. It was a direct and intimate communication, like drinking a cup of water and knowing its coolness firsthand. And when Shakyamuni saw this, he said:

My eye and treasure of the True Law is the awakening of the mysterious mind. True form is without form: This is the subtle entrance to the Dharma. Independent of words and letters, it is transmitted outside the scriptures. It now belongs to Mahakasyapa.

What could be the meaning of this? What had occurred through Shakyamuni? Could something great have been discovered? What do you suppose was transmitted? What was Shakyamuni demonstrating by gently raising the flower? What was it that only Mahakasyapa grasped? Why did he smile upon seeing the flower? And why didn't the others there understand?

The famous Buddhist phrase, "the twirling flower and a smile," points to this event. It was the beginning of the ancestral lineage Transmission of the Light, in Buddhism and Zen. Namely, the Buddhadharma, the import or substance of Shakyamuni Buddha, was personally transmitted, not through words, but directly from mind to mind. Each succeeding ancestral patriarch verifying his predecessor, the succession has continued to the present. This is why all of those who have resolved the gap are referred to as ancestors. All others are only in the realm of explanation based on words. The uniqueness of the Zen sect lies here. It is a fundamental difference arising at the outset. Dogen Zenji wrote:

All the various buddhas are none other than the Buddha Shakyamuni himself. The Buddha Shakyamuni is nothing other than the fact that mind itself is buddha. When the buddhas of the past, present, and future realize enlightenment, they never fail to become the Buddha Shakyamuni. This is the meaning of the mind itself being buddha. Study this question carefully, for it is in this way that you can express your gratitude to the buddhas.

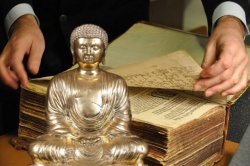

That great event occurring 2500 years ago was the beginning of this single transmission. It established the method of transmitting the true mind of Shakyamuni Buddha. The master verifies inherent objectivity that is grounded in real proof through personal experience. This verification, or Seal of Mind, which serves as a decree of the actualization of inherent objectivity is what Zen is. And, at the same time, it is the starting point of Zen. Consequently, it is called the Great Matter's causal link. Zen is the "Universal Storehouse of the Buddhadharma" because it transmits every aspect of buddha as it is. This Mind of Shakyamuni is called the "Great Vehicle." On the other hand, the records of Shakyamuni's teaching and symbolic deeds soon became forms and intellectual study material to foster a moralistic religious order. This intellectual world is a philosophical and conceptional world that take on the forms of scholarship and the arts to make the flower of Buddhist culture bloom. Because this world has a limited effect in removing the gap to resolve the self, it is called the "Lesser Vehicle" of entering the Dharma.

The mind of the Great Vehicle began with Shakyamuni. After 27 generations in India it declined and disappeared. The Buddhadharma managed to be passed down to the 28th Patriarch, Bodhidharma. Through him it crossed to China where the patriarchal succession continued 6 more generations. Thereafter, great numbers of patriarchs appeared. It became the "Golden Age of Zen." Zen in China had a tremendous influence on Chinese thought, study, and politics. Zen flourished for more than 500 years there before it decayed. And Shakyamuni's Seal of Mind was transmitted to Japan through these many patriarchs of that Golden Age. Eventually, the living Great Vehicle in China extinguished.

The Buddhadharma has gradually moved east. This is the "Eastward Advance of the Dharma." In Japan the teaching of Buddha has overflowed into all aspects of life. In this present day of ours in the demise of the human race, it is truly hoped that the Dharma Gate of the Great Vehicle will be revived for the continuation of a sound and healthy human race.

The theme of riddles, or puzzling problems, beginning at the birth of the first patriarc, the matter of a "communication outside of words," was the start of the treasure hunt for the Buddhadharma. Such riddles become a gateway to realizing the Dharma. These riddles were drawn from the speech and actions of the Chinese patriarchs and took the form of "public questions," or Koans. This method of investigation became the main element of Zen practice called "koan zen." Perhaps koans served notice to intellectuals and scholars of Zen. It was a method that the patriarchs used regularly for checking their disciples.

Koans certainly did not originate in China, nor are they ignored by the Soto Sect which advocates Shikantaza. What do you do with a koan? What don't you do in Shikantaza? Both are nothing more than a means or way. The master used these in accordance with the circumstances of the conceptionalizing student. The only purpose is to remove the gap, or interval. Because sometimes the words and actions of masters of the past were difficult to comprehend, many of those events were recorded for history as public questions and used for reference in Zen practice. Some of the larger collections of these koans include The Blue Cliff Record, the Mumonkan, known as the Gateless Gate, and The Book of Equanimity. Furthermore, all the records of the patriarchs and masters of the past can be considered collections of koans. They are the crystallization of the ancients, and the tears of their efforts. They are the mind of Shakyamuni, and his blood. They are not intended for just anyone to utilize.

The theme of Dogen Zenji's words:

Buddha Shakyamuni is nothing other than the fact that the mind itself is buddha. When the buddhas of the past, present, and future realize enlightenment, they never fail to become the Buddha Shakyamuni. This is the meaning of the mind itself being buddha. Study this question carefully, for it is in this way that you can express your gratitude to the buddhas.

It is an unmistakably clear koan. Plainly, it is the Buddhadharma and the mind of Shakyamuni. The koan is zen practice; it is Shikantaza in itself which, as it is, clarifies itself.

Advancing eastward and having reached Japan, 770 years have already past. It is a sign of the coming extinction of the Buddhadharma when there is no longer anybody yearning for the ancient teachings. This is both frightening and sad.

WHAT DID SHAKYAMUNI BUDDHA TRANSMIT?

Shakyamuni was the son of the prince of Magadha, a large country located in what is now India. He enjoyed many pleasures. But his intellectual growth and expansion fueled his doubts and suffering day by day. The living Buddha had already matured enough that his thoughts were turning inward. Usually one's interests turn outward to externals for pleasure and enjoyment. The response to external stimulation through the doors of perception and the senses is immediate. But from birth Shakyamuni had gone past the stage of external stimulation. In other words, his conception of external stimuli was not founded in personal interests. His fate or reason for living was that each event that took place in his life manifested as a problem. They were the problems of birth, old age, sickness, and death. His view of a festive scene full of beautiful dancers and smiling faces was, "What's the sense of all this? Another day is quickly passing. I'm not amused by it all. Wasting my time at this only piles a sense of futility on top of my suffering." And when the young Shakyamuni looked at flowers blooming in spring, he thought, "Yes, they are beautiful now, but soon they will rot away and look detestable...........people get carried away by seeing a beautiful flower, and deceive themselves all the more by putting on a showy banquet."

Shakyamuni had a beautiful wife of a noble family and one son Ragora. But still he would muse, "Man's life is governed by fate and evolution. In youth we are beautiful and lively. Why does man fall into sickness, become old, and finally die? Neither my parents, wife, child, nor myself can avoid this. How did this severe law of reality come about?" The more he investigated his misery through study and philosophy the more he suffered.

What happened was that his world of pleasure arising from influences on the coarse or lower human response functions was at an end. It is said that Shakyamuni made 8000 journeys to the ordinary world of man. Making this many trips to the regular world he came to the conclusion that no matter how much one indulges in pleasure, the result is sorrow and grief and the realization of the futility of it all. All things and affairs of the phenomenal world eventually decay and uselessly die. Through personal experience Skakyamuni firmly grasped this reality, both conceptually and philosophically. If one's sentiment is moved by deep intellectual understanding and metaphysics and a feeling for transiency, pathos, and nihility, then one's decision-making processes are going to lead in a certain direction. All of his human qualities, including empathy, responsibility, and wisdom had been refined and polished through his 8000 crossings into the world of man. He certainly understood his family's tugs and pleas for more love and attention, but there was something else that had unyieldingly seized him. He had already transcended the self-centered world and reached the absolute, which was his universal Great Doubt. This Great Doubt is what made the man Shakyamuni a Buddha.

This Great Doubt was rooted in the utter futility of all relationships with the common world of humanity. This included his worldly position as king, his castle and possessions, and his home and family. Here his suffering reached its ultimate limit. Finally, greeting his fate, he cut off all worldly relations and threw away his castle. He was nineteen. [Other sources state his age at 29. But this is doubtful because he would have been middle-aged in those days.]

Prepared even to die, he left his castle with six companions in order to resolve the Great Matter. His sights were on the other shore. This was truly an example of Bodaishin, the Mind that seeks the Way. What could stand in his path! Know that Bodaishin itself is the life of the buddhas and patriarchs.

Although this happened over 2500 years ago, all of time is but time itself. What a heartbreaking situation. Whenever I think about this, I shed countless tears in reverence. He truly embraced the Way. We should forever be grateful. Exalted is the World-Honored One Shakyamuni Buddha!

Like all celebrated ascetics, utterly discarding his body he immediately began his practice. He forgot about food and sleep and wished to experience any and all agonies. He was taught that in order to resolve the Great Doubt he must undergo severe ascetic practice. He endured ordeal after ordeal, but his mental functions would not come to a stop. Unfortunately, he practiced terribly hard refusing his doubts time or space to arise, and endured suffering as nobody else had ever done. But when off guard, they immediately appeared again; his doubts and suffering were the same as before he left the castle. Perceptively he came to realize the limits of religious austerities: physical disciplines have no relation with solving the Great Doubt. They would not bring him to his goal. He thought, Study is of no benefit to me. His practice of austerities lasted five years. Clearly, cleanly, and simply braking from ascetic practices, he felt refreshed. But fundamentally his doubts and usual mental condition still had not been resolved in the least. When perception based on the self begins functioning, even without clear cause one becomes confused. And doubts in the form of denial (What's the sense in doing such religious practices?) will arise. But this seems natural. The person who possessed more zeal than anyone else had exhausted all latent physical strength, as well.

He left ascetic life and set out for human habitation. His body had been tortured by the elements, and he was dangerously underweight. Finally he came to a roadside. A farm girl, variously named in the sutras as Sujata or Nandabala, offered him a rice-milk gruel. It was a mysterious event. Reverently taking the milk to his lips, he at once was taken back by his state of mind. ("What could this feeling be?") The taste of the delicious milk, his joy, gratitude, and deep emotion all began flooding him. It left him speechless. That instant his suffering heart caused by the Great Doubt had been cut off. He had never experienced anything like it before. He was full and satisfied. He had failed to notice this heart before. It didn't exist during his ascetic practices. It was his first such experience. He had touched upon the beginning of a new world. [Still, where could that refreshed, satisfied feeling have arisen from? What is this thing called the self? And how can he resolve his original doubts?]

Here Shakyamuni noticed the mysterious workings of the mind: "What is the make up of this mind that makes me suffer, and feel delight alike? Even if one wrestles with the question of his own death, isn't it a matter of the mind itself?" These doubts intensified. Investigating the mind like this is the beginning of Zen. His practice until this time had been unfocused. Instantenously things arose in the mind then disappeared. Things excited the mind, which the mind then amplified. Examining this happening, he realized the unlimited depth and power of the mind itself. And this is where he started focusing his attention. In introspection, he realized that punishing one's body will not temper or toughen the mind, and ascetic practices will not resolve his doubts.

In a river he cleansed his body and refreshed his mind, then regaining his dignity he began to sit under a tree. He tried neither to halt nor restrict the functioning mind. Thoughts and ideas were flowing from morning until night. Thoughts and images of everything imaginable continued to rise, shaking the foundations of his senses. He simply sat, unmoved. And the more he sat, the more helpless he became. He continued like this for many days buried in the emptiness of the mind.

Before long, his attention was totally drawn by fluttering thoughts of when, where, and how these mental phenomenon arise. Shakyamuni's good sense to investigate, totally devoid of any methodology, the mind, indicates his incisive reasoning power. The probable reason for this is he had collected, intensified, and deduced all mental appearances that came to him. Then, scientifically and logically he completely revised them. His conclusion was that these things didn't come from outside, but appear from within oneself. The only way to resolve one's doubts was to thoroughly investigate the root of this. And this must occur in the realm of the immediate and utter present, the instant before any and all working of the mind arises. And Shakyamuni thought here must be the origin of the universe, of all things.

His steering was on course. But how does one do nothing? Without utilizing any means, how do you clarify this world of the present instant, one's present mind?

Shakyamuni's investigation had been thorough up to this stage. But as sagacious as he was, from here he was completely helpless, helpless because the present moment exists prior to consciousness. By the time one becomes aware of something, it is already in the past. It has assumed a form; and it is the traces of the form that we apprehend. That is, the present moment is an empty world in absolute time (i.e., no time, no space) where the intellect does not reach, because it is the domain transcending all existence. The cognitive function itself is a qualified and perverted abstraction of the absolute world of no-time and no-space. Therefore it can never embrace the present moment. Shakyamuni was able to probe this far intellectually. A victim by personally experience, he thoroughly observed the functioning mental faculties. He had pushed the intellect to its limit.

But there was no way he could have understood that the intellectual function of recognition was the cause of the gap, or separation, and the seed of man's confusion. Hence, he could not have realize that throwing away the gap was the decisive means to resolving his Great Doubt. Even so, by the time he had come to see that mind was the world of the present moment and outside our reach, his emotional functions raising feelings of severe self-persecution and suffering caused by the Great Doubt had subsided. He had begun to focus directly on his problem. He had attained a profound serenity from his exhaustive intellectual examination of the mind. He had managed an exhaustive abstract theory on the source of his restlessness, the intellectual friction caused by the Great Doubt. It had now become a matter of a personal relationship with one's senses, perceptions, and consciousness. The world of the senses and cognition is the real, phenomenal world; and due to sense stimulation thoughts endlessly arise. Sagacious Shakyamuni couldn't avoid dealing with this reality.

The senses and perception are real. They are functions of the phenomenal world. Written in the Heart Sutra, Buddha explains to his follower Shariputra:

The six sense organs (eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind) function according to the six sense objects (form, sound, smell, taste, touch, and phenomenon).

The sense functions and our body exist together in equilibrium, but the sense objects merely appear instantaneously. Opening your eyes everything appears optically as it is. Closing them everything vanishes. It is a fact that nothing remains in the eye. Looking in another direction and opening them again, a whole new world momentarily appears. All actions of the senses are completed instanteously; moreover, completely and utterly disappear. This reality of existing-without-existing is dependent merely on causes or circumstances arising due to momentary phenomenon. Shakyamuni was easily able to comprehend and resolve this through personal experience. You can see how extensively he probed into the relationship between phenomenon and the mind. Afterward, he was able to give positive proof that all things in the cosmos functioned naturally and independently, without flaw nor want. He revealed this transcendental state as mu: nothingness.

Clarifying his doubt this far, he was about to make a great discovery: the six sense organs function according to the six sense objects, which appear due to sense stimulation. But he was to make the precise discover that these faculties and their actions are one reality, and pure, which precede the intellectual, conceptual world of thought. One understands if something is hot or cold the moment it is touched. In short, he discovered that it is the ultimate in candidness, absolutely without need of discrimination or any other intellectual functions. Things are just as they are. It is impossible to determine how long it took him to get this far. Groping in the dark as he was refining his investigation and repeating his actual observations, a considerable period of time was probably needed.