Difference between revisions of "The Vows"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Little monk.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Little monk.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | It is possessing formal vows (dompa) that makes someone a monk or a nun. Vows are forms of restraint – formal rules that govern behavior – from the most serious (like killing) to the most minor (like spitting). Monastic vows are forms of physical and verbal control. They govern what a monk may/not do with his body, and what he may/not say with his speech. They do not control mental actions. That is, monastic vows are not restrictions about what monks may/not think. Controlling mental action is considered much more difficult, and even if this is the ultimate goal of Buddhism, monasticism is seen only as a preamble (and in some traditions also as a prerequisite) to this more difficult task of controlling the mind. The | + | It is possessing formal [[vows]] (dompa) that makes someone a [[monk]] or a [[nun]]. [[Vows]] are [[forms]] of restraint – formal rules that govern {{Wiki|behavior}} – from the most serious (like killing) to the most minor (like spitting). [[Monastic]] [[vows]] are [[forms]] of [[physical]] and [[verbal]] control. They govern what a [[monk]] may/not do with his [[body]], and what he may/not say with his [[speech]]. They do not control [[mental]] [[actions]]. That is, [[monastic]] [[vows]] are not restrictions about what [[monks]] may/not think. Controlling [[mental]] [[action]] is considered much more difficult, and even if this is the [[ultimate]] goal of [[Buddhism]], monasticism is seen only as a preamble (and in some [[traditions]] also as a prerequisite) to this more difficult task of controlling the [[mind]]. The [[monks]]’ [[vows]] were meant not only as a way of preparing {{Wiki|individuals}} for [[mental]] training, they were also meant to create well-polished gentlemen: upright and [[noble]] {{Wiki|individuals}} who would bring {{Wiki|honor}} to the community. Part of the goal of the [[monastic]] [[discipline]], therefore, was to create a respectable and dignified community that was [[worthy]] of the reverence and financial support of the laity. |

| − | The Buddha set forth the vows or regulations as situations arose that required him to offer his opinion/verdict about what were acceptable and unacceptable behaviors for his followers. In this sense the vows represent an inductive moral scheme – built up dialectically in conversation with real human actions – rather than an a priori scheme that is deduced from some set of fundamental moral principles or axioms. Insofar as the discipline is based on the authority of the Buddha, it can also be said to be a dogmatic scheme: it was not negotiable, even if, especially in later times, it became an object of interpretation and debate. How did the list of rules for the Buddhist clergy evolve? Typically, a monk or nun would engage in a certain activity that would be noticed, and considered inappropriate, by his or her colleagues. The action or behavior would be brought to the attention of the Buddha, who would intervene by declaring the activity either acceptable or (more frequently) unacceptable. Over the years of the Buddha’s life, these pronouncements came to constitute a list of proscribed actions that governed all aspects of a monk’s life down to the types of robes and shoes that a monk could wear. | + | The [[Buddha]] set forth the [[vows]] or regulations as situations arose that required him to offer his opinion/verdict about what were acceptable and unacceptable behaviors for his followers. In this [[sense]] the [[vows]] represent an inductive [[moral]] scheme – built up dialectically in [[conversation]] with real [[human]] [[actions]] – rather than an a priori scheme that is deduced from some set of fundamental [[moral]] {{Wiki|principles}} or axioms. Insofar as the [[discipline]] is based on the [[authority]] of the [[Buddha]], it can also be said to be a {{Wiki|dogmatic}} scheme: it was not negotiable, even if, especially in later times, it became an [[object]] of interpretation and [[debate]]. How did the list of rules for the [[Buddhist]] clergy evolve? Typically, a [[monk]] or [[nun]] would engage in a certain [[activity]] that would be noticed, and considered inappropriate, by his or her colleagues. The [[action]] or {{Wiki|behavior}} would be brought to the [[attention]] of the [[Buddha]], who would intervene by declaring the [[activity]] either acceptable or (more frequently) unacceptable. Over the years of the [[Buddha’s]] [[life]], these pronouncements came to constitute a list of proscribed [[actions]] that governed all aspects of a monk’s [[life]] down to the types of [[robes]] and shoes that a [[monk]] could wear. |

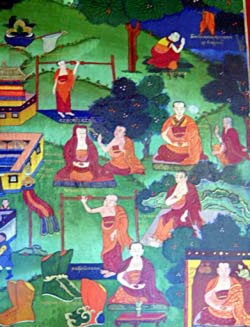

[[File:Mural-robes.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Mural-robes.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | In the Tibetan tradition, that follows the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, the set of proscribed actions came to be codified into a list of two-hundred and fifty-three vows.10 These are further classified into different subcategories according to the gravity of the offense. The most serious, bringing expulsion from the order, are the first four, called “the four defeats” (pampa): | + | In the [[Tibetan tradition]], that follows the [[Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya]], the set of proscribed [[actions]] came to be codified into a list of two-hundred and fifty-three vows.10 These are further classified into different subcategories according to the gravity of the offense. The most serious, bringing expulsion from the [[order]], are the first four, called “the four defeats” (pampa): |

| − | sexual intercourse | + | {{Wiki|sexual}} intercourse |

theft | theft | ||

| − | killing (of a human being) | + | killing (of a [[human]] being) |

false claims about superhuman abilities | false claims about superhuman abilities | ||

| − | Next, there are the “thirteen community-residue” (gendun lhakma chuksum) rules that include transgressions involving: (1-5) sexuality (masturbation, touching a woman out of sexual desire, etc.), (6-7) improper dwelling places (regulations concerning the site where the monk’s hut is to be built, the size of the abode, etc.), (8-9) falsely accusing other monks of having committed a “defeat” transgression, (10-11) creating schisms in the community, and (12-13) refusing to be admonished. Committing one of these offenses does not bring expulsion form the order, but does involve a process of penance, probation, and reinstatement by the community. | + | Next, there are the “thirteen community-residue” ([[gendun]] lhakma chuksum) rules that include transgressions involving: (1-5) {{Wiki|sexuality}} ([[masturbation]], touching a woman out of [[sexual desire]], etc.), (6-7) improper dwelling places (regulations concerning the site where the monk’s hut is to be built, the size of the [[abode]], etc.), (8-9) falsely accusing other [[monks]] of having committed a “defeat” transgression, (10-11) creating schisms in the community, and (12-13) refusing to be admonished. Committing one of these offenses does not bring expulsion [[form]] the [[order]], but does involve a process of penance, probation, and reinstatement by the community. |

[[File:Mural-life.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Mural-life.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Another lesser set of rules involves things incorrectly acquired or held, which have as their penalty the forfeiture of the item in question. Yet another set, requiring confession, involve incorrect speech (lying, being evasive or uncooperative, maligning others etc.), improperly associating with the laity or with other monks, eating improperly, and so forth. Still more minor rules may incur no penalty at all under certain circumstances, but simply set forth what is considered improper behavior. | + | Another lesser set of rules involves things incorrectly acquired or held, which have as their penalty the forfeiture of the item in question. Yet another set, requiring confession, involve incorrect [[speech]] (lying, [[being]] evasive or uncooperative, maligning others etc.), improperly associating with the laity or with other [[monks]], eating improperly, and so forth. Still more minor rules may incur no penalty at all under certain circumstances, but simply set forth what is considered improper behavior. |

| − | In addition to keeping the vows, monks also had to perform certain ritual actions (lé) associated with the Vinaya. Every month on the new and full moon, for example, monks had to perform the purification/confession ritual called sojong. Monks also had to ritually commit themselves to – and ritually release themselves from – the rainy season precepts (e.g., not to travel outside of the official boundary of the monastery for a period of three fortnights). | + | In addition to keeping the [[vows]], [[monks]] also had to perform certain [[ritual]] [[actions]] (lé) associated with the [[Vinaya]]. Every month on the new and [[full moon]], for example, [[monks]] had to perform the purification/confession [[ritual]] called sojong. [[Monks]] also had to [[ritually]] commit themselves to – and [[ritually]] release themselves from – the rainy season [[precepts]] (e.g., not to travel outside of the official boundary of the [[monastery]] for a period of three fortnights). |

| − | In theory, all monks were supposed to abide by these rules, and to undergo the appropriate punishments and penalties if they did not. In practice, few Buddhist communities probably ever followed the Vinaya exactly to the letter. While the Theravāda tradition of Southeast Asia is arguably the strictest of all the Buddhist traditions as regards Vinaya observance today, this emphasis on the discipline has been a relatively recent phenomenon. And even the monks of the Theravāda tradition do not uphold all of the rules and practices exactly as required by the Vinaya. In Tibet, although the Geluk school is known for emphasizing the importance of the monastic life, even the great seats – the densas, its greatest institutions – did not follow the Vinaya very strictly. At Sera, a monk who committed murder or who was caught having sex with a woman was indeed expelled from the monastery.11 He was stripped of his robes, made to wear a white, soiled garment,12 beaten, and physically cast out from the grounds of the monastery. 13 In regard to other rules, however, Tibetan Buddhist monks have always been more lax. For example, some monks engaged in forms of homosexual sex that while, strictly speaking, not constituting an expellable offense, nonetheless constituted infractions of the lesser rules of discipline.14 In other regards as well Tibetan monks were casual in upholding Vinaya regulations. For example, while monks take a vow not to eat after noon, few monks have traditionally observed this precept in Tibet. Those who do – called gongché, or “evening fasters,” literally, “those who have cut off the evening (meal)” – are few in number. There are also restrictions in the Vinaya concerning what type of meat monks can eat (the meat cannot be from an animal that has been slaughtered specifically for monks), but on special occasions the meals that were offered to monks in Sera’s large assemblies required that many animals be slaughtered.15 From sex to food to the size of their rooms to their interactions with lay people, Sera monks were typical of Tibetan Buddhist monks in disregarding – or else simply accepting their laxity in regard to – many of the rules of the Vinaya. Rather than this making them “bad monks,” it probably only makes them typical of the way that the Vinaya, as an ideal system, has always been practiced in the Buddhist world: with a certain amount of flexibility, and a good bit of compromise. | + | In {{Wiki|theory}}, all [[monks]] were supposed to abide by these rules, and to undergo the appropriate punishments and penalties if they did not. In practice, few [[Buddhist]] communities probably ever followed the [[Vinaya]] exactly to the [[letter]]. While the [[Theravāda]] [[tradition]] of [[Southeast]] {{Wiki|Asia}} is arguably the strictest of all the [[Buddhist traditions]] as regards [[Vinaya]] observance today, this emphasis on the [[discipline]] has been a relatively recent [[phenomenon]]. And even the [[monks]] of the [[Theravāda]] [[tradition]] do not uphold all of the rules and practices exactly as required by the [[Vinaya]]. In [[Tibet]], although the [[Geluk]] school is known for emphasizing the importance of the [[monastic]] [[life]], even the great seats – the densas, its greatest {{Wiki|institutions}} – did not follow the [[Vinaya]] very strictly. At [[Sera]], a [[monk]] who committed murder or who was caught having sex with a woman was indeed expelled from the monastery.11 He was stripped of his [[robes]], made to wear a white, soiled garment,12 beaten, and {{Wiki|physically}} cast out from the grounds of the [[monastery]]. 13 In regard to other rules, however, [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[monks]] have always been more lax. For example, some [[monks]] engaged in [[forms]] of homosexual sex that while, strictly speaking, not constituting an expellable offense, nonetheless constituted infractions of the lesser rules of discipline.14 In other regards as well [[Tibetan]] [[monks]] were casual in upholding [[Vinaya]] regulations. For example, while [[monks]] take a [[vow]] not to eat after noon, few [[monks]] have [[traditionally]] observed this [[precept]] in [[Tibet]]. Those who do – called gongché, or “evening fasters,” literally, “those who have cut off the evening (meal)” – are few in number. There are also restrictions in the [[Vinaya]] concerning what type of meat [[monks]] can eat (the meat cannot be from an [[animal]] that has been slaughtered specifically for [[monks]]), but on special occasions the meals that were [[offered]] to [[monks]] in Sera’s large assemblies required that many [[animals]] be slaughtered.15 From sex to [[food]] to the size of their rooms to their interactions with [[lay people]], [[Sera]] [[monks]] were typical of [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[monks]] in disregarding – or else simply accepting their laxity in regard to – many of the rules of the [[Vinaya]]. Rather than this making them “bad [[monks]],” it probably only makes them typical of the way that the [[Vinaya]], as an ideal system, has always been practiced in the [[Buddhist]] [[world]]: with a certain amount of [[flexibility]], and a good bit of compromise. |

[[File:Monk on pilgrimage.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Monk on pilgrimage.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [10] For a complete listing of these, see Charles S. Prebish, Buddhist Monastic Discipline: The Sanskrit Pratimokṣa Sūtras of the Mahāsāṃghikas and Mūlasarvāstivādins (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1974). | + | [10] For a complete listing of these, see Charles S. Prebish, [[Buddhist]] [[Monastic]] [[Discipline]]: The [[Sanskrit]] Pratimokṣa [[Sūtras]] of the [[Mahāsāṃghikas]] and [[Mūlasarvāstivādins]] ({{Wiki|University}} Park: The Pennsylvania State {{Wiki|University}} Press, 1974). |

| − | [11] It remains to be seen how severely the other two “defeats” were dealt with. | + | [11] It {{Wiki|remains}} to be seen how severely the other two “defeats” were dealt with. |

| − | [12] White is the symbol of the Buddhist laity, since in India lay people wore white; using a soiled garment is symbolic of the individual’s now polluted or “defeated” status. | + | [12] White is the [[symbol]] of the [[Buddhist]] laity, since in [[India]] [[lay people]] wore white; using a soiled garment is [[symbolic]] of the individual’s now polluted or “defeated” status. |

| − | [13] See the accounts of Tashi Khedrup in “The Life of a Dob Dob,” | + | [13] See the accounts of Tashi Khedrup in “The [[Life]] of a Dob Dob,” |

| − | [14] Since monks were discrete about sexual encounters and relationships of this sort, we do not really know how widespread such practices were. | + | [14] Since [[monks]] were discrete about {{Wiki|sexual}} encounters and relationships of this sort, we do not really [[know]] how widespread such practices were. |

| − | From anecdotal evidence it seems that it was more prevalent among adolescent boys, and that it tapered off later in life. The dopdop (on which, see below) were especially renowned for their homosexual liaisons. A typical form of sexual contact involved copulation between the thighs of the partner, a sexual action that avoided an expellable offense (“defeat”) since it did not involve penetration of the mouth or anus of the partner. Nor, it would seem, were such relationships only between monks. Melvyn C. Goldstein et al., ed., The Struggle for Modern Tibet: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering (Armonck: M.E. Sharpe, 1997), 26-30, offers us details of such a relationship between an older monk official and a young non-monk dancer (Tashi Tsering himself). Tashi Tsering also describes how he was abducted by a Sera dopdop on more than one occasion. | + | From anecdotal {{Wiki|evidence}} it seems that it was more prevalent among adolescent boys, and that it tapered off later in [[life]]. The dopdop (on which, see below) were especially renowned for their homosexual liaisons. A typical [[form]] of {{Wiki|sexual}} [[contact]] involved copulation between the thighs of the partner, a {{Wiki|sexual}} [[action]] that avoided an expellable offense (“defeat”) since it did not involve [[penetration]] of the {{Wiki|mouth}} or anus of the partner. Nor, it would seem, were such relationships only between [[monks]]. Melvyn C. Goldstein et al., ed., The Struggle for {{Wiki|Modern}} [[Tibet]]: The Autobiography of [[Tashi Tsering]] (Armonck: M.E. Sharpe, 1997), 26-30, offers us details of such a relationship between an older [[monk]] official and a young non-monk dancer ([[Tashi Tsering]] himself). [[Tashi Tsering]] also describes how he was abducted by a [[Sera]] dopdop on more than one occasion. |

| − | [15] Today, at Sera-India, the monastery serves no meat to monks, or even to lay patrons (even if individual monks continue to buy and to eat meat). But this is a recent departure from custom. | + | [15] Today, at Sera-India, the [[monastery]] serves no meat to [[monks]], or even to lay patrons (even if {{Wiki|individual}} [[monks]] continue to buy and to eat meat). But this is a recent departure from custom. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

Revision as of 07:47, 6 September 2013

It is possessing formal vows (dompa) that makes someone a monk or a nun. Vows are forms of restraint – formal rules that govern behavior – from the most serious (like killing) to the most minor (like spitting). Monastic vows are forms of physical and verbal control. They govern what a monk may/not do with his body, and what he may/not say with his speech. They do not control mental actions. That is, monastic vows are not restrictions about what monks may/not think. Controlling mental action is considered much more difficult, and even if this is the ultimate goal of Buddhism, monasticism is seen only as a preamble (and in some traditions also as a prerequisite) to this more difficult task of controlling the mind. The monks’ vows were meant not only as a way of preparing individuals for mental training, they were also meant to create well-polished gentlemen: upright and noble individuals who would bring honor to the community. Part of the goal of the monastic discipline, therefore, was to create a respectable and dignified community that was worthy of the reverence and financial support of the laity.

The Buddha set forth the vows or regulations as situations arose that required him to offer his opinion/verdict about what were acceptable and unacceptable behaviors for his followers. In this sense the vows represent an inductive moral scheme – built up dialectically in conversation with real human actions – rather than an a priori scheme that is deduced from some set of fundamental moral principles or axioms. Insofar as the discipline is based on the authority of the Buddha, it can also be said to be a dogmatic scheme: it was not negotiable, even if, especially in later times, it became an object of interpretation and debate. How did the list of rules for the Buddhist clergy evolve? Typically, a monk or nun would engage in a certain activity that would be noticed, and considered inappropriate, by his or her colleagues. The action or behavior would be brought to the attention of the Buddha, who would intervene by declaring the activity either acceptable or (more frequently) unacceptable. Over the years of the Buddha’s life, these pronouncements came to constitute a list of proscribed actions that governed all aspects of a monk’s life down to the types of robes and shoes that a monk could wear.

In the Tibetan tradition, that follows the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, the set of proscribed actions came to be codified into a list of two-hundred and fifty-three vows.10 These are further classified into different subcategories according to the gravity of the offense. The most serious, bringing expulsion from the order, are the first four, called “the four defeats” (pampa):

sexual intercourse

theft

killing (of a human being)

false claims about superhuman abilities

Next, there are the “thirteen community-residue” (gendun lhakma chuksum) rules that include transgressions involving: (1-5) sexuality (masturbation, touching a woman out of sexual desire, etc.), (6-7) improper dwelling places (regulations concerning the site where the monk’s hut is to be built, the size of the abode, etc.), (8-9) falsely accusing other monks of having committed a “defeat” transgression, (10-11) creating schisms in the community, and (12-13) refusing to be admonished. Committing one of these offenses does not bring expulsion form the order, but does involve a process of penance, probation, and reinstatement by the community.

Another lesser set of rules involves things incorrectly acquired or held, which have as their penalty the forfeiture of the item in question. Yet another set, requiring confession, involve incorrect speech (lying, being evasive or uncooperative, maligning others etc.), improperly associating with the laity or with other monks, eating improperly, and so forth. Still more minor rules may incur no penalty at all under certain circumstances, but simply set forth what is considered improper behavior.

In addition to keeping the vows, monks also had to perform certain ritual actions (lé) associated with the Vinaya. Every month on the new and full moon, for example, monks had to perform the purification/confession ritual called sojong. Monks also had to ritually commit themselves to – and ritually release themselves from – the rainy season precepts (e.g., not to travel outside of the official boundary of the monastery for a period of three fortnights).

In theory, all monks were supposed to abide by these rules, and to undergo the appropriate punishments and penalties if they did not. In practice, few Buddhist communities probably ever followed the Vinaya exactly to the letter. While the Theravāda tradition of Southeast Asia is arguably the strictest of all the Buddhist traditions as regards Vinaya observance today, this emphasis on the discipline has been a relatively recent phenomenon. And even the monks of the Theravāda tradition do not uphold all of the rules and practices exactly as required by the Vinaya. In Tibet, although the Geluk school is known for emphasizing the importance of the monastic life, even the great seats – the densas, its greatest institutions – did not follow the Vinaya very strictly. At Sera, a monk who committed murder or who was caught having sex with a woman was indeed expelled from the monastery.11 He was stripped of his robes, made to wear a white, soiled garment,12 beaten, and physically cast out from the grounds of the monastery. 13 In regard to other rules, however, Tibetan Buddhist monks have always been more lax. For example, some monks engaged in forms of homosexual sex that while, strictly speaking, not constituting an expellable offense, nonetheless constituted infractions of the lesser rules of discipline.14 In other regards as well Tibetan monks were casual in upholding Vinaya regulations. For example, while monks take a vow not to eat after noon, few monks have traditionally observed this precept in Tibet. Those who do – called gongché, or “evening fasters,” literally, “those who have cut off the evening (meal)” – are few in number. There are also restrictions in the Vinaya concerning what type of meat monks can eat (the meat cannot be from an animal that has been slaughtered specifically for monks), but on special occasions the meals that were offered to monks in Sera’s large assemblies required that many animals be slaughtered.15 From sex to food to the size of their rooms to their interactions with lay people, Sera monks were typical of Tibetan Buddhist monks in disregarding – or else simply accepting their laxity in regard to – many of the rules of the Vinaya. Rather than this making them “bad monks,” it probably only makes them typical of the way that the Vinaya, as an ideal system, has always been practiced in the Buddhist world: with a certain amount of flexibility, and a good bit of compromise.

[10] For a complete listing of these, see Charles S. Prebish, Buddhist Monastic Discipline: The Sanskrit Pratimokṣa Sūtras of the Mahāsāṃghikas and Mūlasarvāstivādins (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1974).

[11] It remains to be seen how severely the other two “defeats” were dealt with.

[12] White is the symbol of the Buddhist laity, since in India lay people wore white; using a soiled garment is symbolic of the individual’s now polluted or “defeated” status.

[13] See the accounts of Tashi Khedrup in “The Life of a Dob Dob,”

[14] Since monks were discrete about sexual encounters and relationships of this sort, we do not really know how widespread such practices were.

From anecdotal evidence it seems that it was more prevalent among adolescent boys, and that it tapered off later in life. The dopdop (on which, see below) were especially renowned for their homosexual liaisons. A typical form of sexual contact involved copulation between the thighs of the partner, a sexual action that avoided an expellable offense (“defeat”) since it did not involve penetration of the mouth or anus of the partner. Nor, it would seem, were such relationships only between monks. Melvyn C. Goldstein et al., ed., The Struggle for Modern Tibet: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering (Armonck: M.E. Sharpe, 1997), 26-30, offers us details of such a relationship between an older monk official and a young non-monk dancer (Tashi Tsering himself). Tashi Tsering also describes how he was abducted by a Sera dopdop on more than one occasion.

[15] Today, at Sera-India, the monastery serves no meat to monks, or even to lay patrons (even if individual monks continue to buy and to eat meat). But this is a recent departure from custom.