Difference between revisions of "Who is the Buddha?"

m (Text replace - "ordinary" to "ordinary") |

m (Text replace - "to pass" to "to pass") |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

This is true, but you can go deeper than this. The abrupt [[attainment]] of [[Enlightenment]], you may say, has [[nothing]] to do with speed within [[time]]. It doesn't mean that you begin the usual process of attaining [[Enlightenment]] and get through it more quickly. It doesn't mean that whereas you might normally spend fifteen or fifty years on the gradual [[path]], you are somehow able to speed it up and compress it into a year, or even a month, or a week, or a weekend. The abrupt [[path]] is outside [[time]] altogether. Sudden [[Enlightenment]] is simply the point at which this new [[dimension]] of eternity outside [[time]] is entered. You can never get closer to eternity by speeding up your approach to it within [[time]]. Within [[time]] you just have to stop. At the same [[time]], of course, you can't stop without first having speeded up. So [[Enlightenment]] can be looked at from two points of [[view]], both of which are valid. It can be regarded as the culmination of the evolutionary process, a culmination which is reached through personal [[effort]]. But [[Enlightenment]] can also be regarded as [[being]] a sort of breakthrough into a new [[dimension]] beyond [[time]] and [[space]]. | This is true, but you can go deeper than this. The abrupt [[attainment]] of [[Enlightenment]], you may say, has [[nothing]] to do with speed within [[time]]. It doesn't mean that you begin the usual process of attaining [[Enlightenment]] and get through it more quickly. It doesn't mean that whereas you might normally spend fifteen or fifty years on the gradual [[path]], you are somehow able to speed it up and compress it into a year, or even a month, or a week, or a weekend. The abrupt [[path]] is outside [[time]] altogether. Sudden [[Enlightenment]] is simply the point at which this new [[dimension]] of eternity outside [[time]] is entered. You can never get closer to eternity by speeding up your approach to it within [[time]]. Within [[time]] you just have to stop. At the same [[time]], of course, you can't stop without first having speeded up. So [[Enlightenment]] can be looked at from two points of [[view]], both of which are valid. It can be regarded as the culmination of the evolutionary process, a culmination which is reached through personal [[effort]]. But [[Enlightenment]] can also be regarded as [[being]] a sort of breakthrough into a new [[dimension]] beyond [[time]] and [[space]]. | ||

| − | There is a rather picturesque story which vividly illustrates the {{Wiki|paradoxical}} meeting of these two dimensions. It concerns a famous bandit, called [[Angulimala]], who lived in a great forest somewhere in {{Wiki|northern India}}. Angulimala's speciality was to ambush travellers on their way through the forest, murder them, and chop off one of their fingers as a trophy. These fingers he strung into a garland which he wore round his neck; hence his name, [[Angulimala]], meaning 'garland of fingers'. It was his [[ambition]] to have one hundred fingers on his garland, and he had got to ninety-eight when the [[Buddha]] happened | + | There is a rather picturesque story which vividly illustrates the {{Wiki|paradoxical}} meeting of these two dimensions. It concerns a famous bandit, called [[Angulimala]], who lived in a great forest somewhere in {{Wiki|northern India}}. Angulimala's speciality was to ambush travellers on their way through the forest, murder them, and chop off one of their fingers as a trophy. These fingers he strung into a garland which he wore round his neck; hence his name, [[Angulimala]], meaning 'garland of fingers'. It was his [[ambition]] to have one hundred fingers on his garland, and he had got to ninety-eight when the [[Buddha]] happened to pass through that forest. The village folk had tried to dissuade him from entering it, warning him that he was in [[danger]] of losing a finger - and his [[life]] - to the notorious [[Angulimala]], but the [[Buddha]] had carried on regardless. The [[sight]] of him just about made Angulimala's day, because he had been getting a bit desperate to find the last two fingers for his garland. His mother, a devoted old [[soul]], was living with him in the forest and cooking for him, and he had got so fed up with waiting he had finally decided there was [[nothing]] for it but to add one of her fingers to his collection (maybe she used to nag him a bit). That would make ninety-nine, so he would just need one more. He had been on his way to find his poor old mother when he saw the [[Buddha]] coming through the forest. He [[thought]], 'Well, I can always deal with mother later. But first I will settle the hash of this . Finger number ninety-nine coming up!' |

[[File:Buddha22.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddha22.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

It was a [[beautiful]] afternoon, a gentle breeze stirring the tree-tops and the birds singing, when the [[Buddha]] came walking along the little trail that wound through the forest. He walked meditatively, slowly, [[thinking]] to himself or, perhaps, not [[thinking]] at all. [[Angulimala]] emerged from the forest, and stealthily began to tail the [[Buddha]], creeping up on him from behind. He had his sword drawn ready, so he could make very quick work of his prey when he got close to him. He loped along smoothly and rapidly to cut down the distance between them before he was seen. The last thing he wanted was a long messy struggle. | It was a [[beautiful]] afternoon, a gentle breeze stirring the tree-tops and the birds singing, when the [[Buddha]] came walking along the little trail that wound through the forest. He walked meditatively, slowly, [[thinking]] to himself or, perhaps, not [[thinking]] at all. [[Angulimala]] emerged from the forest, and stealthily began to tail the [[Buddha]], creeping up on him from behind. He had his sword drawn ready, so he could make very quick work of his prey when he got close to him. He loped along smoothly and rapidly to cut down the distance between them before he was seen. The last thing he wanted was a long messy struggle. | ||

Revision as of 11:35, 8 September 2013

By now we know a good deal about the Buddha. We know that he was born in the Lumbini garden, we know how he was educated, we know how he left home, how he gained Enlightenment at the age of thirty-five, how he communicated his teaching, how he founded his Sangha, and how, finally, he passed away. And there is a good deal more we could find out. The traditional biographies give us all the facts. We could find out the names of the Buddha's half-brothers and cousins, the name of the town where he was brought up, the name of the astrologer who came to see him as a baby. But although his life is fully documented, although we've got the whole story, does his biography really tell us who the Buddha was? Do we know the Buddha from a description of the life of Gautama the Buddha?

What do we mean by 'knowing' the Buddha anyway? In what sense, really, do we know anybody? Suppose you are told all about someone: where they live, what they do - the sort of things people always want to know about a person - how old they are, and so on. In some sense you have an answer to the question, 'Who is this person?' You know their social identity, their position in society. Gradually you can fill in any number of details - how tall they are, their accent, their background, their taste in food and music, their political affiliations and their religious beliefs. You can then say you know about this person. But however much you know about someone, you would not claim to know them until you'd met them, until you'd met them a few times, probably. You'd then know them personally. This deeper knowledge would, in fact, be based on a relationship, on communication: you know someone, properly speaking, when they also know you. Eventually you may claim to know this person very well.

But is it really so? Do you really know them? After all, it sometimes happens that we have to correct our evaluation of someone. Sometimes we are taken completely by surprise. They do something quite unexpected, quite 'out of character', and we say to ourselves, rather surprised and sometimes a little hurt, 'Well, I never would have expected them to do that. They're the last person I'd have thought would do that.' But they did it, and this shows how little we really know other people. We are not truly able to fathom the deepest springs of their action, their fundamental motivation. This happens even with those who are supposedly nearest and dearest to us. It's a wise child that knows its own father, as the saying goes - and it's a wise father or mother that knows his or her own child.

Particularly, perhaps, it is a wise husband that knows his own wife, and a wise wife that knows her own husband. Sometimes I've had the experience of meeting - separately - a husband and wife, each having come to talk to me about the other. And usually what happens is that each gives a picture of the other that I would never have recognized. The impression I've had is that neither really knows the other. It's as though the so-called closeness gets in the way, and what we know is not the other person to whom we are supposed to be so close, but only our own projected mental state, our own quite subjective reaction to that person. In other words, our ego gets in the way.

In order really to know another person we have to go much deeper than the ordinary level of communication - which means, in effect, that ordinary communication is not real communication at all. It's just the same when it comes to knowing the Buddha. We may know all the biographical facts about his life, but are we thereby any nearer really knowing the Buddha? Well, no. The question continues to arise: Who was the Buddha? This question has been asked since the very dawn of Buddhism. In fact, the first question that was put to the Buddha after his Enlightenment was, 'Who are you?'

Walking along the road one day, the Buddha met a brahmin called Dona. As he saw the Buddha in the distance, coming towards him, there was something about the approaching figure that stopped Dona dead in his tracks. There were plenty of singular-looking individuals walking about India at that time - Dona himself was one of them - but Dona could see that this individual coming towards him was somehow utterly different from anyone he had ever seen. The Buddha, after all, was just fresh from his Enlightenment. He was happy, serene, and joyful; there was a radiance about his whole being, as though a light were shining from his face.

As the Buddha drew near, Dona asked him, 'Who are you?' Not 'Lovely weather we're having,' or 'Where are you from?' but 'Who are you?' If you were standing at the bus stop waiting for the bus into town and someone came up and said, 'Who are you?' you'd probably think they were being rather impertinent, but in India, of course, it's different, and Dona could put this question without fear of giving offence. The point is that Dona was not asking who the Buddha was in social terms; he was not asking what sort of a human being the Buddha was. Dona was, in fact, wondering if this was really a human being at all that he was seeing.

The ancient Indians believed that the universe was stratified into various levels of existence. There were not just human beings and animals, as we tend to think. There were also gods and ghosts and yakshas and gandharvas - all sorts of mythological beings - inhabiting a sort of multi-storey universe. The human plane was just one out of scores of planes of existence. Dona's first thought, therefore, impressed as he was by the appearance of the Buddha, was, 'This isn't a human being. He must be from - or on his way to - some other realm. Perhaps he's a sort of spirit.' So he asked the Buddha, 'Who are you? Would you be a deva?' - a deva being a god, a divine being, a sort of archangel. The Buddha simply said, 'No.' So Dona tried again. 'Are you a gandharva?' This creature is like a kind of celestial musician, a beautiful, singing, angelic figure. The Buddha again said, 'No.' 'Well,' said Dona, 'Are you a yaksha?' A yaksha is a sort of sublime spirit, rather a terrifying one, who lives in the jungle. But the Buddha rejected this designation as well. Then Dona thought, 'He must be a human being after all. That's strange.' So he asked, 'Are you a human being?' (the kind of question you could only ask in ancient India) and once again the Buddha said, 'No.' 'Well, that is odd,' Dona thought. 'If he isn't a deva, or a gandharva, or a yaksha, or a human being, what on earth is he?' 'Who are you?' he asked, now even more wonderingly. 'If you are none of these things, who are you? What are you?'

The Buddha said, 'Those conditions (or, perhaps better, those psychological conditionings) on account of which I might have been described as a deva or a gandharva or a yaksha or a human being have been destroyed. Therefore am I a Buddha.' It is, as we have seen, these conditioned mental attitudes, volitions, or karma formations as they are sometimes called, which according to Buddhism (and Indian belief in general) determine our rebirth, as well as our human condition here and now. The Buddha was free from all this, free from all conditioning, so there was nothing to cause him to be reborn as a god or a gandharva, or even a human being. Even as he stood before this Brahmin, therefore, he was not any of these things. His body might appear to be that of a man, but his mind, his consciousness, was unconditioned, and therefore he was a Buddha. As a Buddha he was a personification, so to speak - even, if you like, an incarnation - of the Unconditioned mind.

What Dona tried to do is what we all try to do when we meet something new. The human mind proceeds slowly, by degrees, from the known to the unknown, and we try to describe the unknown in terms of the known; which is fair enough so long as one is aware of the limitations of this procedure. And we may say that the limitations of this procedure are most pronounced when it comes to trying to know other human beings.

There always seems to be a basic tendency to want to put people in categories and think that we have thereby got them neatly pigeon-holed. In India I have often been stopped in the road by someone just passing, who has said, 'What is your caste?' - without any sort of preamble. If they can't classify you according to caste, they don't know what to do with you. They don't know how to treat you. They don't know whether they can take water from your hand or not, whether they can get to know you or not, whether you might marry their daughter or not. All these things are very important, especially in southern India. In Britain people are much more indirect in their approach, but they try to worm out of you the same sort of information. They want to know what sort of job you've got (and perhaps from that they try to work out your income), they want to know where you were born, where you were educated, where you live now, and by taking these various sociological readings, they gradually narrow down the field, and think they've got you nicely pinned down.

So likewise, when Dona saw this majestic, radiant figure, and wanted to know who - or what - it was, he had at his disposal various labels - gandharva, yaksha, deva, human being - and he tried to stick these labels on what he saw. But the Buddha wouldn't have it. His reply said, in effect, 'None of these labels fit. None of them apply. I'm a Buddha. I transcend all conditionings. I am above and beyond all this.'

Dona may have been one of the first to puzzle over the Buddha's nature, but he was certainly not the last. We have already come across four of the Fourteen Inexpressibles: whether the Buddha would exist after death, or not, or both, or neither. Although the Buddha was constantly being asked about this - the ancient Indians had a real thing about it - he would always say that it was inappropriate to apply any of those four statements to a Buddha. And he would go on to say, 'Even during his lifetime, even when he sits there in a physical body, the Buddha is beyond all your classifications. You can't say anything about him.'(footnote 29)

This point is easily made, of course, but actually very difficult to accept, and it evidently needed to be constantly hammered home. The most suggestive and evocative repudiation of any attempt to grasp the nature of the Buddha is found in the Dhammapada: 'Whose conquest is not to be undone, whom not even a bit of those conquered passions follows, that Enlightened One whose sphere is endless, by what path will you trace him, the pathless one?'(footnote 30) According to this well-known verse, therefore, there is absolutely nothing by which a Buddha can be identified or tracked down or classified or categorized. You cannot trace the path of a bird's flight by looking for signs of its passage in the sky - and you cannot track a Buddha either.

If this is clear, however, it has not really been understood. It is somehow the nature of the human mind to keep on trying, and to imagine that, having understood what is being said, it understands what it is that is being spoken of. So if we turn to the Sutta Nipata, we find the Buddha saying:

There is no measuring of man,

Won to the goal, whereby they'd say

His measure's so: that's not for him.

When all conditions are removed,

All ways of telling are removed.(footnote 31)

When all psychological conditions are removed in a person, you have no way of accounting for that person. You can't say anything about the Buddha because he doesn't have anything. In a sense, he isn't anything. In fact, we are introduced in this sutta to an epithet for an Enlightened being which says just this. Akincana, usually translated as 'man of nought', is one who has nothing because he is nothing. And of nothing, nothing can be said.

Although many of the Buddha's disciples gained Enlightenment, and themselves went through the world leaving no trace, as it were, they still worshipped the Buddha. They still felt there was something about him, about the man who discovered the Way for himself with no one to guide him, that was mysteriously beyond them and unfathomable. Even his chief disciple, Sariputra, floundered when it came to estimating the Buddha's stature. He was once in the presence of the Buddha when, out of an excess of faith and devotion, he exclaimed, 'Lord, I think you are the greatest of all the Enlightened Ones who have ever existed, or will exist, or exist now. I think you are the greatest of them all.' The Buddha was neither pleased nor displeased by this. He didn't say, 'What a marvellous disciple you are, and how wonderfully well you understand me!' He just asked a question: 'Sariputra, have you known all the Buddhas of the past?' Sariputra said, 'No, Lord.' Then he said, 'Have you known all the Buddhas of the future?' 'No, Lord.' 'Do you know all the Buddhas that now are?' 'No, Lord.' Finally, the Buddha asked 'Do you even know me?' And Sariputra said, 'No, Lord.' Then the Buddha said, 'That being the case, Sariputra, how is it that your words are so bold and so grand?'(footnote 32)

So even the closest of his disciples didn't really know who the Buddha was. To try to make sense of this attitude, they put together, after his death, a list of ten powers and eighteen special qualities which they attributed to the Buddha just to distinguish him from his Enlightened disciples. But in a way this was just an expression of the fact that they simply could not understand who or what he was at all.

This fact that the Enlightened disciples of the Buddha, enjoying personal contact with him, did not understand who he really was does not say much for our own chances in the matter. However, at a certain level, we can build up a collection of hints and clues, and the episode with Dona offers an important lead. What it is suggesting is that we have to step back and bring in a whole new dimension to our search for the Buddha. He is untraceable because he belongs to a different dimension, the transcendental dimension, the dimension of eternity.

So far we have seen him very much in terms of time - his birth, his Enlightenment, his death - his historical existence. We have, in fact, been looking at him according to the evolutionary model we introduced in the first chapter, which model is, of course, one of progress through space and time. This, however, is only one way of looking at things. As well as looking at the Buddha from the standpoint of time, we can also look at him from the standpoint of eternity.

The problem with any biographical account of the Buddha is that in a sense it deals with two quite different people: Siddhartha and the Buddha - divided by the central event of the Enlightenment. But one tends to come away from the biographical facts with the view that his early life simply built up to this point, and that after it he was more or less the same as he was before - apart from being Enlightened, of course. If we had been around at the time we should probably have been none the wiser. If we had known the Buddha a few months before he was Enlightened and a few months after, we should almost certainly not have been able to perceive any difference in him at all. We would have seen the same physical body, probably the same clothes. He spoke the same language and had the same general characteristics. This being so, we tend to regard the Buddha's Enlightenment as a finishing touch to a process which had been going on for a long time, the feather that turned the scale, the final piece of the jigsaw, that little difference that made all the difference. But really it isn't like that at all - not in the least like that.

Enlightenment - the Buddha's or anybody else's - represents 'the intersection of the timeless moment.'(footnote 33) We need to modify T.S. Eliot's analogy a little, because strictly speaking only a line can intersect another line, and although we can represent time as a line, the whole point of the timeless - eternity - is that it isn't a line. Perhaps we should think rather in terms of time as a line which at a given point just stops, just disappears into another dimension. It's rather like - to use a hackneyed but (if we don't take it too literally) rather useful simile - the flowing of a river into the ocean, where the river is time and the ocean is eternity. Perhaps, indeed, we can improve on the simile to some extent. Suppose we imagine that the ocean into which our river is flowing is just over the horizon. From where we are, we can see the river flowing to the horizon, but we can't see the ocean into which the river is flowing, so it seems as though the river is flowing into nothingness, flowing into a void. It just stops at the horizon because that is the point at which it enters the new dimension which we cannot see.

The point of intersection is what we call Enlightenment. Time just stops at eternity; time is succeeded, so to speak, by eternity. Siddhartha disappears, like the river disappearing at the horizon, and the Buddha takes his place. This is, of course, from the standpoint of eternity. Whereas from the standpoint of time Siddhartha becomes, evolves into, the Buddha, from the standpoint of eternity Siddhartha just ceases to exist, and there is the Buddha, who has been there all the time.

This difference of approach - in terms of time and in terms of eternity - is at the bottom of the whole controversy between the two schools of Zen, the gradual school and the abrupt school. In the early days of Zen (or rather Ch'an) in China, there were two apparently opposing viewpoints: there were those who believed that Enlightenment was attained in a sudden flash of illumination; and there were those who believed that it was attained gradually, step by step, by patient effort and practice. In the Platform Sutra Hui Neng tries to clear up the whole controversy: he says it isn't that there are two paths, a gradual one and a sudden one; it is merely that some people gain Enlightenment more quickly than others, presumably because they make a greater effort.

This is true, but you can go deeper than this. The abrupt attainment of Enlightenment, you may say, has nothing to do with speed within time. It doesn't mean that you begin the usual process of attaining Enlightenment and get through it more quickly. It doesn't mean that whereas you might normally spend fifteen or fifty years on the gradual path, you are somehow able to speed it up and compress it into a year, or even a month, or a week, or a weekend. The abrupt path is outside time altogether. Sudden Enlightenment is simply the point at which this new dimension of eternity outside time is entered. You can never get closer to eternity by speeding up your approach to it within time. Within time you just have to stop. At the same time, of course, you can't stop without first having speeded up. So Enlightenment can be looked at from two points of view, both of which are valid. It can be regarded as the culmination of the evolutionary process, a culmination which is reached through personal effort. But Enlightenment can also be regarded as being a sort of breakthrough into a new dimension beyond time and space.

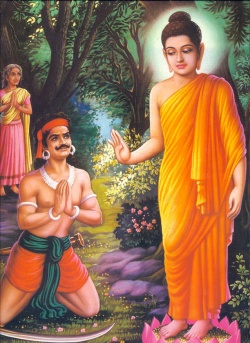

There is a rather picturesque story which vividly illustrates the paradoxical meeting of these two dimensions. It concerns a famous bandit, called Angulimala, who lived in a great forest somewhere in northern India. Angulimala's speciality was to ambush travellers on their way through the forest, murder them, and chop off one of their fingers as a trophy. These fingers he strung into a garland which he wore round his neck; hence his name, Angulimala, meaning 'garland of fingers'. It was his ambition to have one hundred fingers on his garland, and he had got to ninety-eight when the Buddha happened to pass through that forest. The village folk had tried to dissuade him from entering it, warning him that he was in danger of losing a finger - and his life - to the notorious Angulimala, but the Buddha had carried on regardless. The sight of him just about made Angulimala's day, because he had been getting a bit desperate to find the last two fingers for his garland. His mother, a devoted old soul, was living with him in the forest and cooking for him, and he had got so fed up with waiting he had finally decided there was nothing for it but to add one of her fingers to his collection (maybe she used to nag him a bit). That would make ninety-nine, so he would just need one more. He had been on his way to find his poor old mother when he saw the Buddha coming through the forest. He thought, 'Well, I can always deal with mother later. But first I will settle the hash of this . Finger number ninety-nine coming up!'

It was a beautiful afternoon, a gentle breeze stirring the tree-tops and the birds singing, when the Buddha came walking along the little trail that wound through the forest. He walked meditatively, slowly, thinking to himself or, perhaps, not thinking at all. Angulimala emerged from the forest, and stealthily began to tail the Buddha, creeping up on him from behind. He had his sword drawn ready, so he could make very quick work of his prey when he got close to him. He loped along smoothly and rapidly to cut down the distance between them before he was seen. The last thing he wanted was a long messy struggle.

After he had followed the Buddha for a while, however, he noticed that something rather odd was happening. Although he seemed to be moving much more quickly than the Buddha, he didn't seem to be getting any closer to him. There was the Buddha way in front, pacing slowly, and there was Angulimala shadowing him and trying to catch up, but not getting any nearer. Angulimala quickened his pace, and then he was running, but he still got no nearer to the Buddha. When Angulimala realized what was happening, he apparently broke into a cold sweat of terror and astonishment and bewilderment. But he was not a man to give up easily - or to stop and think about things either. He just lengthened his stride till he was sprinting along in the wake of the Buddha. The Buddha, however, stayed just the same distance ahead, and if anything he seemed to be going even more slowly. It was like a bad dream.

In desperation, Angulimala called out to the Buddha: 'Stand still!' The Buddha turned round and said, 'I am standing still. It is you who are moving.' So Angulimala, who had considerable presence of mind despite his fear - for he was a bold fellow - said, 'You are supposed to be a shramana, a holy man. How can you tell such a lie? Here am I running like mad, and I can't catch up with you. What do you mean, you are standing still?' The Buddha said, 'I am standing still because I am standing in nirvana. I have come to rest. You are moving because you are going round and round in samsara.'(footnote 34)

Of course, Angulimala becomes the Buddha's disciple, but that, and what happens afterwards, is another story. What this particular adventure illustrates is that Angulimala could not catch up with the Buddha because the Buddha was moving - or standing still, it is the same thing here - in another dimension. Angulimala, representing time, couldn't catch up with the Buddha, representing eternity. However long time goes on, it never comes to a point where it catches up with eternity. Time doesn't find eternity within the temporal process. Angulimala couldn't have caught up with the Buddha even if the Buddha had come to a dead halt. He could still be running now, after 2,500 years, but he still wouldn't have caught up with the Buddha.

When the Buddha attained Enlightenment, he entered a new dimension of being. There was no continuity, essentially, from the person who was there before. He was not just the old Siddhartha slightly improved, or even considerably improved, but a new person. This is actually a very difficult thing to grasp, it needs reflecting on, because we naturally think of the Buddha's Enlightenment in terms of our own experience of life. In the course of our lives we may add to our knowledge, learn different things, do different things, go to different places, meet different people, life teaches us things - but underneath we remain fundamentally and recognizably the same person. Whatever changes take place don't go that deep. 'The child is father to the man' - that is, what one is now is determined to a remarkable degree by what one was as a child. One remains much the same person as one was then. The conditions for one's fundamental attitude to life were set up a long time ago, and any change that takes place subsequently is comparatively superficial. This even applies to our commitment to a spiritual path. We may take to Buddhism, we may 'go for Refuge' to the Buddha, but the change isn't usually very deep.

But the Buddha's experience of Enlightenment wasn't like that. In reality it wasn't an experience at all, because the person to have the experience wasn't there any more. The 'experience' of Enlightenment is therefore more like death. It is more like the change that takes place between two lives, when you die to one life and are reborn in another. In some Buddhist traditions Enlightenment is called 'the great death', because everything of the past dies, everything, in a way, is annihilated, and you are completely reborn. In the case of the Buddha, it is not that he was a smartened up version of Siddhartha, Siddhartha tinkered about with a bit, Siddhartha reissued in a new edition. Siddhartha was finished. At the foot of the bodhi tree Siddhartha died and the Buddha was born - or we should say, rather, that he 'appeared'. At that moment, when Siddhartha dies, the Buddha is seen as having been alive all the time - by which we really mean above and beyond time, out of time altogether.

Even to talk in this way is again misleading, because it is not as if, being outside time, you are really outside anything. Time and <$Ispace>space are not things in themselves. We usually think of space as a sort of box within which things move about, and time as a sort of tunnel along which things move - but they are not really like that. Space and <$Itime>time are really forms of our perception. We see things through the spectacles, as it were, of space and time. And we speak of these things that we see as phenomena - which are, of course, what make up the world of relative, conditioned existence, or samsara. So what we call phenomena are only realities as seen under the forms of space and time. But when we enter the dimension of eternity, we go beyond space and time, and therefore we go beyond the world, we go beyond samsara, and, in the Buddhist idiom, we enter nirvana.

Enlightenment is often described as awakening to the truth of things, seeing things as they really are, not as they appear to be. The Enlightened person sees things free from any veils or obscurations, sees them without being influenced or affected by any assumptions or psychological conditionings, sees them with perfect objectivity - not only sees them, but becomes one with them, one with the reality of things. So the Buddha, the one who has awoken to the Truth, the one who exists out of time in the dimension of eternity, may be regarded as Reality itself in human form. This is what is meant by saying that the Buddha is an Enlightened human being: the form is human, but in the place, so to speak, of the conditioned human mind, with all its prejudices and preconceptions and limitations, there is Reality itself, there is an experience or awareness which is not separate from Reality.

In the Buddhist tradition this crystallized eventually into a very important distinction which came to be established with regard to the Buddha. On the one hand there was his rupakaya (literally 'form body'), his physical phenomenal appearance; on the other, there was, or rather is, his dharmakaya (literally 'body of Truth' or 'body of Reality'), his true, his essential, form. The rupakaya is the Buddha as existing in time, but the dharmakaya is the Buddha as existing out of time in the dimension of eternity. Wherein lies the true nature of the Buddha, in his rupakaya or his dharmakaya, is declared definitively in a chapter from one of the great Perfection of Wisdom texts, the Diamond Sutra. In it the Buddha says to his disciple, Subhuti:

Those who followed me by voice,

Wrong the effort they engaged in.

Me those people will not see.

From the Dharma should one see the Buddhas,

From the Dharma-bodies comes their guidance.

Yet Dharma's true nature cannot be discerned,

And no one can be conscious of it as an object.(footnote 35)

The Buddha is found to be equally emphatic on this point in the Pali canon. Apparently there was a monk called <$IVakkali>Vakkali who was very devoted to the Buddha, but his devotion had got stuck at a superficial level. He was so fascinated by the appearance and the personality of the Buddha that he used to spend all his time sitting and looking at him, or following him around. He didn't want any teaching. He didn't have any questions to ask. He just wanted to look at the Buddha. So one day the Buddha called him and said, 'Vakkali, this physical body is not me. If you want to see me, you must see the Dharma, you must see the dharmakaya, my true form.'(footnote 36) So Vakkali meditated on this, and he gained liberation by meditating in this way very shortly before he died.

Vakkali's problem is actually one that most of us have. It's not that we should ignore the physical body, but we should take it as a symbol of the dharmakaya, the Buddha as he is in his ultimate essence. That said, it must be admitted that the word Buddha is ambiguous. When, for instance, we say, 'The Buddha spoke the language of Magadha,' we are obviously referring to Gautama the Buddha, the historical figure. On other occasions, however, 'Buddha' means the transcendental Reality, as when we say, 'Look for the Buddha within yourself.' Here we don't mean Gautama the Buddha; we mean the eternal, time-transcending Buddha-nature within ourselves. Broadly speaking, the Theravada School today uses the word Buddha more in the historical sense, whereas the Mahayana, especially Zen, tends to use it more in the spiritual, trans-historical sense.

The shifting usage of this word only adds to the confusion Westerners are liable to feel when it comes to identifying the Buddha. Like Dona, we want to know who the Buddha is, we want to slap a label on him. But with our Western, dualistic, Christian background we have only two labels available to us: God and Man. Some people tend to say that the Buddha was just a man - a very good man, a very holy man, very decent, but just a man, no more than that. He's someone rather like Socrates. This is the view taken, for instance, by Catholic writers about Buddhism. It's a rather subtle, insidious approach. They praise the Buddha for his wonderful piety, wonderful charity, great love, compassion, wisdom - yes, he's a very great man. Then, on the last page of their book about Buddhism, they carefully add that of course the Buddha was just a man, and not to be compared with Christ, who was, or is, the son of God. This is one way in which the Buddha gets misplaced. The other way people fail to see him is by saying, 'No, the Buddha is a sort of god for the Buddhists. Of course, he was originally a man, but then, hundreds of years after his death, those misguided Buddhists went and made him into a god, because they wanted to have something to worship.'

Both these views are wrong, and the source of this misconception probably lies in a general misunderstanding of what religion is necessarily about. People for whom the idea of a non-theistic religion is a contradiction in terms will always want to resolve the question of how the Buddha stands in relation to God. Christ is said by his followers to be the son of God. Muhammad is supposed to be the messenger of God. The Jewish prophets claim to be inspired by God. And Krishna and Rama are claimed to be incarnations of God. Indeed, many Hindus think of the Buddha as one as well. They look upon him as the ninth incarnation, the ninth avatar, of the god Vishnu. This is how they see him because the category of avatar is a familiar one to them. But neither the Buddha nor his followers make any such claim, because Buddhism is a non-theistic religion. Like some other religions - Taoism, Jainism, and certain forms of philosophical Hinduism - in Buddhism there is no place for God at all. There is no supreme being, no creator of the universe, and there never has been. So Buddhists can worship as much as they like, but they will never be worshipping their creator or any conception of a personal God.

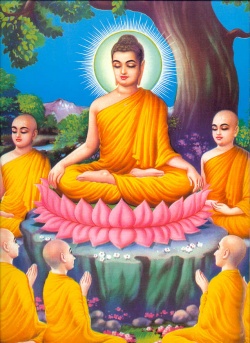

The Buddha is neither man nor God, nor even a god. He was a human being in the sense that he started off as every other human being starts off, but he didn't remain an ordinary human being. He became an Enlightened human being, and according to Buddhism that makes a great deal of difference - in fact, all the difference. He was an Unconditioned mind in a conditioned body. According to the Buddhist tradition, a Buddha is the highest being in all the universe, higher even than the so-called gods (whom in Western terms we would call angels, archangels, and so on). Traditionally the Buddha is called the teacher of gods and men, and in Buddhist art the gods are represented in a very humble position, saluting the Buddha and listening to his teaching. Therefore there is no possibility, whether on a philosophical or a popular level, of confusing the Buddha with any kind of god.

For those of us brought up to imagine that if anyone is the highest being in the universe that person is God, it is not so easy to really discern the Buddha in that position. Even if we don't believe in God, we see a God-shaped empty space, and the Buddha simply does not measure up to it. After all, he has not created the universe. We see the Buddha in this way because there's a category missing, we may say, from Western thought. If, therefore, we are to perceive who the Buddha is we have to dispel the ghost of God, the creator of the universe that looms over him, by substituting for God something completely different.

After all this, are we any nearer to answering the question, 'Who is the Buddha?' We've seen that Buddha means Unconditioned mind, Enlightened mind. Knowing the Buddha therefore means knowing the mind in its Unconditioned state. So the answer to the question 'Who is the Buddha?' is really that we ourselves are the Buddha - potentially. We really, truly come to know the Buddha only in the course of our spiritual life, in the course of our meditation, in the course of actualizing our own potential Buddhahood. It is only then that we can really say, from knowledge and experience, who the Buddha is.

We can't do this all at once. It certainly can't be done in a day. First of all we have to establish a living contact with the Buddha. We have to arrive at something intermediate between mere factual knowledge about Gautama the Buddha - the details of his career - and on the other hand, the experience of Unconditioned mind. This intermediate stage is what we call <$IGoing for Refuge>Going for Refuge to the Buddha. And it means not just reciting 'Buddham saranam gacchami' ('to the Buddha for Refuge I go'), though it doesn't exclude that. It means committing ourselves to the goal of Enlightenment as a living ideal, as our ultimate objective, and striving to realize it. It is only by Going for Refuge to the Buddha, with all that this implies, with all that this means, that we can answer from the heart and the mind and the whole of our spiritual life the question: 'Who is the Buddha?